Abstract

Background/Aims

Gastric mucus should be removed before endoscopic examination to increase visibility. In this study, the effectiveness of premedication with pronase for improving visibility during endoscopy was investigated.

Methods

From April 2010 to February 2011, 400 outpatients were randomly assigned to receive endoscopy with one of four premedications as follows: dimethylpolysiloxane (DMPS), pronase and sodium bicarbonate with 10 minutes premedication time (group A, n=100), DMPS and sodium bicarbonate with 10 minutes premedication time (group B, n=100), DMPS, pronase and sodium bicarbonate with 20 minutes premedication time (group C, n=100), and DMPS and sodium bicarbonate with 20 minute premedication time (group D, n=100). One endoscopist, who was unaware of the premedication types, calculated the visibility scores (range, 1 to 3) of the antrum, lower gastric body, upper gastric body and fundus. The sum of the scores from the four locations was defined as the total visibility score.

Results

Group C showed significantly lower scores than other groups (p=0.002). Group C also had the lowest frequency of flushing, which was significantly lower than that of group D. Groups C and D had significantly shorter durations of examination than groups A and B.

Conclusions

Using pronase 20 minutes before endoscopy significantly improved endoscopic visualization and decreased the frequency of water flushing.

Keywords: Pronase, Premedication

INTRODUCTION

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as a neoplasm confined to the mucosa or submucosa regardless of regional lymph node metastasis.1 The rate of EGC, which varies by country, accounts for 40% to 60% of all gastric cancer cases in Japan and 0% to 15% in the UK and other Western countries.2,3 EGC is a curable disease regardless of its location, histologic type, or genetic changes, and has an excellent 5-year survival rate of more than 90% following resection, which is in contrast to the dismal 5-year survival rate of 10% to 20% for advanced gastric cancer.4 Therefore, early detection of EGC is important. Endoscopy is the most commonly used screening test for EGC. However, the endoscopic view is often obscured by the presence of bubbles and mucus on the gastric mucosa.5 To improve visibility during endoscopy, the gastric mucus should be as completely removed as possible.6

Pronase, an enzyme that was first isolated from the culture filtrate of Streptomyces griseus in 1962, can disrupt the gastric mucus by a mucolytic effect.7 In 1964, Koga and Arakawa8 used pronase to remove gastric mucus for roentgenographic examination. And then, Ida et al.9 have applied this enzyme as a premedication for endoscopy.

This study was performed since there have not been many studies reporting the effectiveness of premedication with pronase for improving visibility during endoscopy in this area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From April 2010 to February 2011, 400 patients who were referred to our department for upper gastrointestinal screening endoscopy were included in this study. We excluded patients with previous gastric surgery, gastric malignancy, corrosive gastric injury, gastrointestinal bleeding, current pregnancy, other malignancy or stenosis of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Kosin University Gospel hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Premedication and endoscopic procedure

Endoscopic procedures were performed by a single experienced endoscopist between 9:00 AM and 1:00 PM in the endoscopy room of Kosin University Gospel Hospital. CF-H260AL video endoscope (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used for endoscopy.

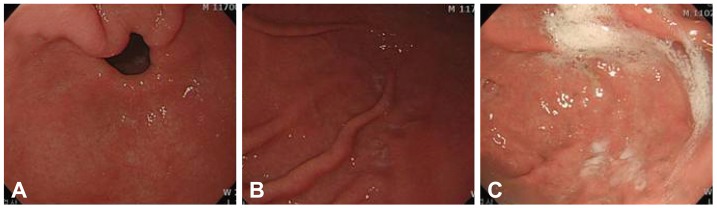

After informed consent was obtained, patients were randomized using the sealed envelope technique to assign them into one of the following four premedication strategies: 1) 100 mL of warm water containing 80 mg of dimethylpolysiloxane (DMPS) (Gasocol; Taejoon Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea), 1 g of sodium bicarbonate and 20,000 units of pronase (endonase; Pharmbio Korea, Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) with 10 minutes premedication duration (group A); 2) 100 mL of warm water containing 80 mg of DMPS and 1 g of sodium bicarbonate with 10 minutes premedication duration (group B); 3) 100 mL of warm water containing 80 mg of DMPS, 1 g of sodium bicarbonate and 20,000 units of pronase with 20 minutes premedication duration (group C); and 4) 100 mL of warm water containing 80 mg of DMPS and 1 g of sodium bicarbonate with 20 minutes premedication duration (group D). The investigator was blinded to the type of premedication assigned to each patients when deciding whe-ther or not to enroll the patients. After removal of excess gastric solution, the endoscopist checked the mucosal visibility of the gastric antrum, the greater curvature of the gastric lower body, the greater curvature of the gastric upper body, and the fundus. The scoring system was as follows: score 1, indicating no adherent mucus and clear view of the mucosa; score 2, a thin coating of mucus but no obscured vision; and score 3, adherent mucus obscuring vision. The sum of the scores from the four locations was defined as the total mucosal visibility score (MVS) (Fig. 1). The duration of endoscopy was defined as the time it took to perform complete stomach examination excluding the time for biopsy and flushing. Fifty milliliter of warm water flushing was counted as one flushing.

Fig. 1.

Mucosal visibility score. (A) Score 1, no adherent mucus and clear view of the mucosa. (B) Score 2, a thin coating of mucus without obscured vision. (C) Score 3, adherent mucus obscuring vision.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics were assessed using a chi-square test. The visibility scores, duration of endoscopy and frequency of water flushing of the four groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple comparisons. The results were shown as mean±standard deviation. Calculated p-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Power calculation

To estimate whether pronase is a significantly effective gastric mucosa cleanser, 280 patients were needed to be recruited (p<0.05, 95% power). Due to follow-up loss and data errors, additional patients were registered.

RESULTS

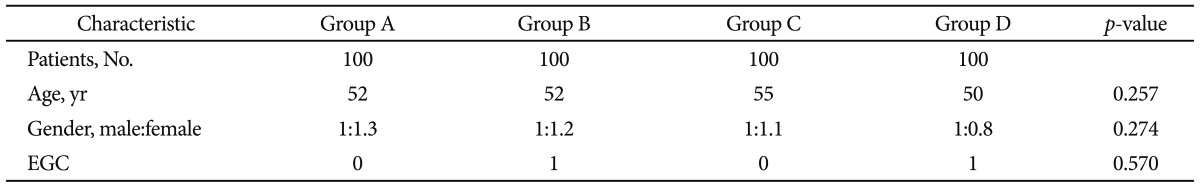

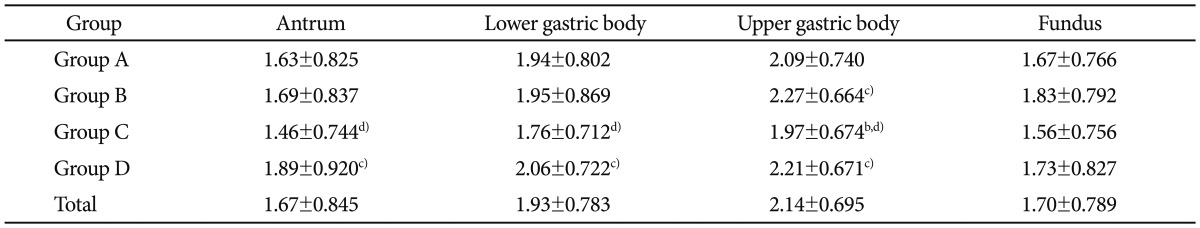

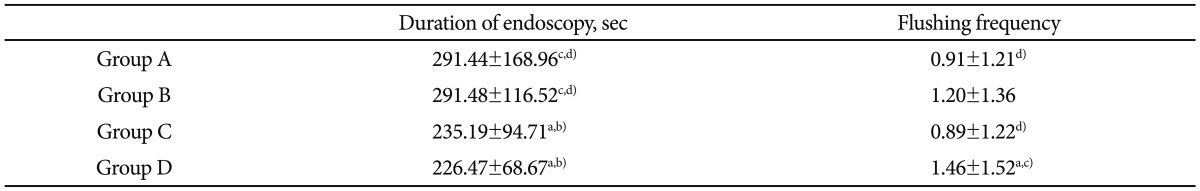

Of the 400 patients, each 100 patients were randomly enrolled into groups A, B, C, and D. The median ages of groups A, B, C, and D were 52, 52, 55, and 50 years, respectively. The ratios of male to female among groups A, B, C, and D were 1: 1.3, 1:1.2, 1:1.1, and 1:0.8, respectively. Two cases of EGC were noted each from group B and D. There were no significant differences among the four groups with respect to sex, age or detection of EGC (Table 1). There were no serious adverse events in any of the groups during the examinations. One endoscopist individually assessed the visibility scores for each patient. The MVS of the four groups are shown in Table 2. The mean MVS was the lowest in group C (p=0.002) (Table 2). As shown in Table 3, the best visibility score was observed in the antrum of all groups. The greater curvature of upper body had the worst visibility score. Except for the fundus, group C had significantly better MVSs than group D. The mean endoscopy durations of group C (235.19±94.71) and group D (226.47±68.67) were significantly shorter than those of groups A (291.44±168.96) and B (291.48±116.52). The mean frequency of water flushing was decreased the most in group C (0.89±1.22). Group C had a significantly lower frequency of water flushing than group D (1.46±1.52) (Table 4).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients of Each Groups

Group A, dimethylpolysiloxane (DMPS), sodium bicarbonate and pronase with 10 minutes premedication time; Group B, DMPS and sodium bicarbonate with 10 minutes premedication time; Group C, DMPS, sodium bicarbonate and pronase with 20 minutes premedication time; Group D, DMPS and sodium bicarbonate with 20 minutes premedication time. ECG, early gastric cancer.

Table 2.

Mucosal Visibility Scores

Values are presented as mean±SD.

Table 3.

Mucosal Visibility Scores at Different Locations of the Stomach

Values are presented as mean±SD.

a)p<0.05 vs. group A; b)p<0.05 vs. group B; c)p<0.05 vs. group C; d)p<0.05 vs. group D.

Table 4.

The Mean Duration of Endoscopy and Water Flushing Frequency

Values are presented as mean±SD.

a)p<0.05 vs. group A; b)p<0.05 vs. group B; c)p<0.05 vs. group C; d)p<0.05 vs. group D.

DISCUSSION

Proper premedication before endoscopy is important to ensure satisfactory visualization of the gastric wall. In the present study, we found that the administration of pronase 20 minutes before endoscopy significantly improved visibility during endoscopy. Also, pronase premedication decreased the frequency of water flushing, although not the duration of endoscopy.

For complete removal of gastric mucus with pronase, we considered several factors that might affect the activity of pronase. Since the maximal mucolysis by pronase was found to occur at pH 6 to 8, it is necessary to neutralize the acidity of the gastric juice with a neutralizer (e.g., NaHCO3) or succinate buffer and to prevent subsequent hypersecretion of gastric juice with a parasympathetic blocker such as scopolamine butylbromide.10

In previous studies, patients were asked to rotate for complete clearance of gastric mucus,7,9 which we did not. Given that the premedication fluid flowed into the gastric fundus, then gradually into the gastric antrum, we thought it was not necessary to change position as in the previous studies.

Although the optimal quantity, density and time of premedication with pronase have not yet been established, previous studies recommended them as below. Ida et al.9 obtained good results using 80 mL of warm water containing DMPS, sodium bicarbonate and pronase. Fujii et al.7 used 100 mL of warm water containing the same components as the above and found that premedication with pronase significantly improved the visibility. In our study, we also used 100 mL warm water with DMPS, sodium bicarbonate and pronase to observe significantly better mucosal visibility. Therefore, patients were recommended to receive 80 to 100 mL of oral solution.

In the previous studies, patients who received 20,000 units pronase with sodium bicarbonate and DMPS for premedications resulted in better MVS than those of other groups.7,10 In our study, we also used 20,000 units of pronase and got the same result. However, Kuo et al.11 used premedication with only 2,000 units pronase, 1.2 g of sodium bicarbonate, 100 mg of DMPS and up to 100 mL of warm water, which resulted in the clearest mucosal visibility. It may be concluded that 2,000 units or more of pronase are sufficient to affect mucosal visibility.

Fujii et al.7 gave premedications around 10 minutes before endoscopy, while Chang et al.10 gave premedications around 20 minutes before endoscopy. We compared the effects of these durations of premedication on mucosal visibility. In our study, there was no significant difference in MVS between group A (10-minute premedication) and group C (20-minute premedication). This suggests that the duration of premedication dose not play a significant role in satisfactory mucosa visualization. Our study is the first to statistically evaluate the effect of the duration of premedication with pronase on mucosal visibility

Some studies have shown that premedication with a defoaming agent and acetylcystein, a mucolytic agent, with pronase can significantly improve the visibility.7,9,11

In our study, MVS was the highest in the upper gastric body and the lowest in the antrum across all groups. We speculate that the exposure time to the ingested premedication fluid contributed to such results.

This study demonstrates that the administration of pronase 20 minutes before endoscopy improves the endoscopic visualization and decreases the frequency of water flushing significantly. We found that the greater curvature of the upper gastric body had the poorest mucosal visibility among all locations. Thus, endoscopists are required to observe this area more carefully.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Kosin University Research Fund of 2010.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimizu S, Tada M, Kawai K. Early gastric cancer: its surveillance and natural course. Endoscopy. 1995;27:27–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talley NJ, Silverstein MD, Agréus L, Nyrén O, Sonnenberg A, Holtmann G. AGA technical review: evaluation of dyspepsia. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:582–595. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borie F, Rigau V, Fingerhut A, Millat B French Association for Surgical Research. Prognostic factors for early gastric cancer in France: Cox regression analysis of 332 cases. World J Surg. 2004;28:686–691. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee B, Parker J, Waits W, Davis B. Effectiveness of preprocedure simethicone drink in improving visibility during esophagogastroduodenoscopy: a double-blind, randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:264–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald GB, O'Leary R, Stratton C. Pre-endoscopic use of oral simethicone. Gastrointest Endosc. 1978;24:283. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(78)73542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii T, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, et al. Effectiveness of premedication with pronase for improving visibility during gastroendoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:382–387. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koga M, Arakawa K. On the application of enzymatic mucinolysis in X-ray diagnosis of the stomach. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 1964;24:1011–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ida K, Okuda J, Nakazawa S, et al. Clinical evaluation of premedication with KPD (Pronase) in gastroendoscopy-placebo-controlled double blind study in dye scattering endoscopy. Clin Rep. 1991;25:1793–1804. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang CC, Chen SH, Lin CP, et al. Premedication with pronase or N-acetylcysteine improves visibility during gastroendoscopy: an endoscopist-blinded, prospective, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:444–447. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo CH, Sheu BS, Kao AW, Wu CH, Chuang CH. A defoaming agent should be used with pronase premedication to improve visibility in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2002;34:531–534. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]