With an anticipated 9.8 million new cases this year,[1] the tuberculosis (TB) epidemic is one of the most serious health problems worldwide. The continuous emergence and global spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of TB, underscore the pressing clinical need for novel treatments of this deadly infectious disease and for new solutions to alleviate the resistance problem.[2, 3]

Aminoglycoside (AG) antibiotics[4] such as kanamycin A (KAN) (1) and amikacin (AMK) (2) are currently used as a last resort for treatment of XDR-TB (Fig. 1A). However, resistance to KAN is constantly rising and treatment options for patients affected with XDR-TB becoming fewer.[5] In most bacterial strains, a major mechanism of resistance to AGs is the enzymatic modification of the drugs by AG-modifying enzymes such as AG acetyltransferases (AACs), AG phosphotransferases (APHs), and AG nucleotidyltransferases (ANTs).[6, 7] In Mtb, resistance to AGs results either from mutations of the ribosome that prevent the drugs from binding to it,[8-10] or from upregulation of the chromosomal eis(enhanced intracellular survival) gene caused by mutations in its promoter.[11, 12] Other biological functions of the mycobacterial protein Eis have been the subject of numerous investigations.[13-20] We recently demonstrated that Eis is a unique AAC that inactivates a broad set of AGs via a multi-acetylation mechanism[21].

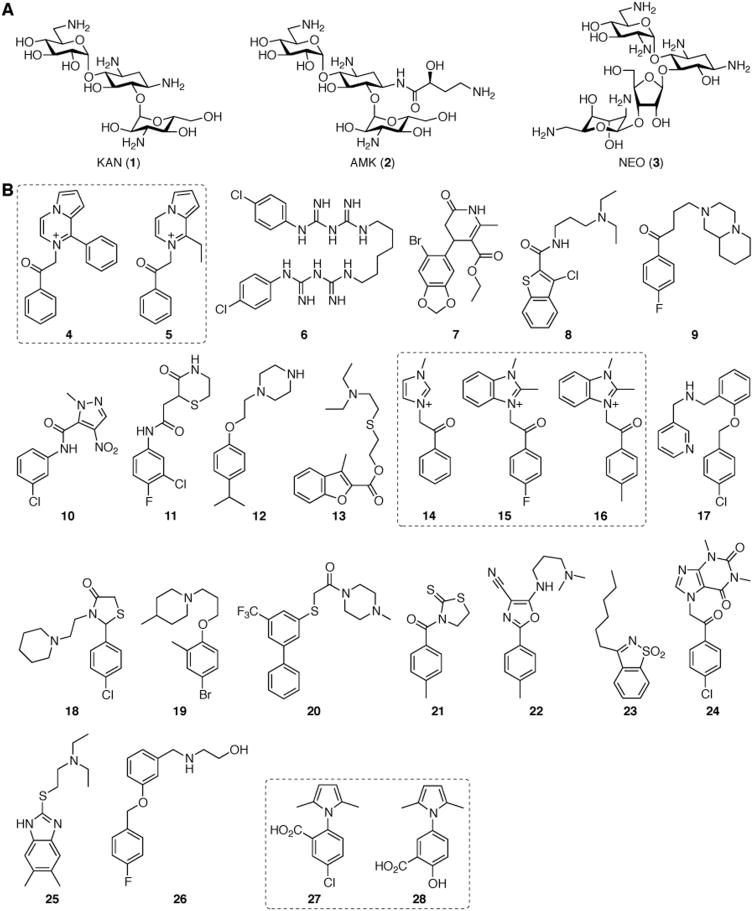

Figure 1.

A. Structures of AGs used in this study. B. Structures of the 25 inhibitors of Eis identified via high-throughput screening.

Two main strategies to overcome the effect of Eis in Mtb could be envisioned: (1) the development of new AGs not susceptible to Eis and (2) the utilization of Eis inhibitors. We recently reported a chemoenzymatic methodology[22] and a complementary protecting-group free chemical strategy[23] for the production of novel AG derivatives. However, as Eis is capable of multi-acetylation of a large variety of AG scaffolds, it is unlikely that novel AGs will provide a viable and/or sustainable solution to the resistance problem in Mtb. Blanchard and co-workers previously showed that, when used in conjunction, the β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanate and meropenem are effective against XDR-TB.[24] The AG tobramycin and the macrolide antibiotic clarithromycin have also showed promising synergistic effect in Mtb clinical isolates.[25] Wright and colleagues also demonstrated that, in general, combinations of antibiotics and non-antibiotic drugs could result in enhancement of antimicrobial efficacy.[26] Similarly, an inhibitor of the resistance acetyltransferase Eis in combination with the currently used second-line antituberculosis drugs KAN or AMK may provide a potential solution to overcome the problem of XDR-TB. Herein, by using in vitro high-throughput screening, we identified and characterized the first series of potent inhibitors of Eis (Fig. 1B).

To identify inhibitors of Mtb Eis, we used neomycin B (NEO)(3) due to the robust activity of the enzyme with this AG. We screened a total of 23,000 compounds from three small molecule libraries: the ChemDiv, the BioFocus NCC, and the MicroSource MS2000 spectrum libraries. From the 23,000 molecules tested, 300 (1.3%) showed a reasonable degree of inhibition (> 3σ from the mean negative control) against Eis, out of which 56 showed dose-dependent inhibition. The 25 compounds discussed herein (Fig. 1B) were found to have IC50 values in the low micromolar range (Table 1 and Figs. 2, S1, and S2). While most of these have not been previously biologically characterized, compounds 7, 14, 27, and 28 have found application as anti-HIV treatments (27[27, 28] and 28[27-29]), molecules to prolong eukaryote longevity (7),[30] antibacterials (27 and 28),[31] anticancer agents (28),[32] and hypoglycemia therapeutics (14)[33].

Table 1.

Eis inhibition constants (IC50) of hit compounds (Compd) 4-28 for NEO acetylation.[a]

| Compd[b] | IC50 (μM)[c] | Compd[b] | IC50 (μM)[c] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 4 | 0.364 ± 0.032 | 15 | 3.24 ± 0.32 |

| 4 | 0.331 ± 0.082 (AMK)[a] | 16 | 3.84 ± 0.55 |

| 4 | 0.585 ± 0.113 (KAN)[a] | 17 | 3.39 ± 0.61 |

| 5 | 9.25 ± 1.50 | 18 | 4.90 ± 0.75 |

| 6 | 0.188 ± 0.030 | 19 | 5.54 ± 0.63 |

| 6 | 0.321 ± 0.058 (AMK)[a] | 20 | 5.68 ± 0.88 |

| 6 | 0.666 ± 0.193 (KAN)[a] | 21 | 5.75 ± 0.66 |

| 7 | 1.09 ± 0.14 | 22 | 6.50 ± 1.32 |

| 8 | 1.24 ± 0.16 | 23 | 7.64 ± 0.60 |

| 9 | 2.01 ± 0.12 | 24 | 9.79 ± 1.97 |

| 10 | 2.29 ± 0.52 | 25 | 11.4 ± 1.6 |

| 11 | 2.37 ± 0.41 | 26 | 15.9 ± 2.6 |

| 12 | 2.63 ± 0.60 | 27 | > 200 |

| 13 | 2.64 ± 0.36 | 28 | 41 ± 9 |

| 14 | 3.06 ± 0.56 | ||

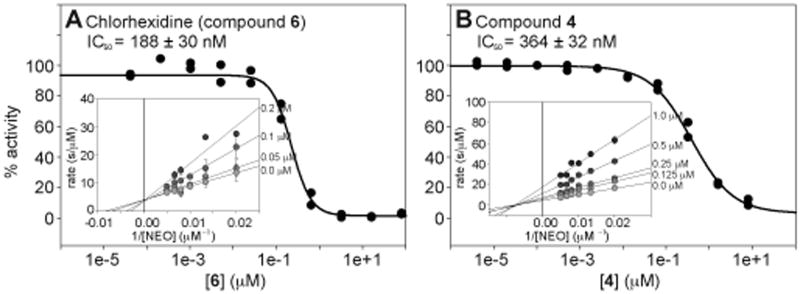

Figure 2.

Representative examples of IC50 curves for A. chlorhexidine (6) and B. compound 4. The plots showing the competitive and mixed inhibition with respect to NEO for compounds 6 and 4, respectively, can be viewed as the inset in each panel.

At a first glance, the 25 identified compounds appear to have vastly different structures. However, upon closer inspection of their scaffolds, two structural features link these 25 Eis inhibitors: the presence of at least (i) one aromatic ring and (ii) one amine functional group. In general, we observed that positively or potentially positively charged molecules, including chlorhexidine (6), displayed lower IC50 values than preferably negatively charged (27 and 28) or neutral compounds. The highly negatively charged AG-binding cavity of the Eis protein (PDB: 3R1K)[21] is consistent with this general trend.

Seven of the 25 Eis inhibitors identified were divided into three groups for a preliminary and limited structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis: (i) compounds 4 and 5, (ii) 14, 15, and 16, as well as (iii) 27 and 28 (Fig. 1B). Compounds 14, 15, and 16 differ in their imidazolium vs benzoimidazolium substitution on one side of the ketone and in their para- substitutents on the phenyl ring on the opposite side of the carbonyl. These differences had no effect on the IC50 values, indicating the importance of the imidazolium, but a secondary role of the additional features to the core structure for biological activity. In contrary, the differences in benzyl ring substitutions in compounds 27 and 28 (alternative placement (ortho- vs meta-) of the carboxylic acid and replacement of the para-chloro group with a para-hydroxyl group) resulted in a >5-fold increase in the inhibition of Eis. Similarly, replacement of the ethyl group of 5 adjacent to the cationic nitrogen by a phenyl moiety in 4 resulted in a 25-fold increase in the inhibitory ability of compound 4. Further kinetic analysis of compound 4 revealed a mixed mode of inhibition against NEO (Fig. 2B). The observed mixed mode of inhibition could be explained by the three substrates (NEO, acetyl-NEO, and diacetyl-NEO) that are produced during the reaction of NEO with Eis. Here, compound 4, may be competing differently with each possible substrate.

Interestingly, in contrast to compound 4, the best inhibitor identified in this study with an IC50 value of 188 ± 30 nM, chlorhexidine (6), was found to behave as an AG-competitive inhibitor against NEO, KAN, and AMK (Fig. 2A). Chlorhexidine is an antibiotic used mainly as a topical antibacterial, as a mouthwash, and as a sterilizing agent for surgical equipment.[34] Because of its toxic effects on pulmonary tissues,[35] chlorhexidine cannot be pursued as a potential TB treatment, but will continue to serve as a positive control for future HTS experiments for identification of additional Eis inhibitor scaffolds.

With their structurally diverse scaffolds, the remaining compounds cannot be divided by structural groups for SAR analyses. However, grouping the compounds by their IC50 values does reveal some trends. In comparison with compounds 4 and 6-8, the fewer hydrogen bonding sites of compounds 9-13 could explain the relatively higher IC50 values for these molecules. Likewise, the increased structural rigidity of compounds 17-26 could limit the ability of the molecules to adapt an ideal conformation for binding, potentially explaining the higher inhibitory constants observed for these molecules.

Because many AACs have a negatively charged AG-binding site that could be accessible for ligand binding,[36-38] in order to confirm the specificity of the identified inhibitors for Eis, we tested whether the four best compounds (4, 6, 7, and 8) inhibited other AAC enzymes with negatively charged AG-binding sites from three different classes: AAC(2′)-Ic from Mtb, AAC(3)-IV from Escherichia coli, and AAC(6′)/APH(2″) from Staphylococcus aureus. With the exception of compound 4 with AAC(2′)-Ic, which displayed an IC50 value of 367 ± 129 μM (1000-fold worse than with Eis), no significant inhibition was observed for the combinations tested. This lack of cross-inhibition indicates that the inhibitors identified display high selectivity towards the Eis AG-binding site. Eis has been shown to multi-acetylate a large number of aminoglycosides(Ref) and is therefore potentially able to accommodate various conformations of structurally diverse and/or similar molecules in contrast to the mono-acetylating AACs (AAC(2′), AAC(3), and AAC(6′)) for which substrates can only bind in a single conformation. The unique flexibility of the AG-binding site of Eis could therefore explain the intriguing selectivity of the inhibitors identified for this enzyme. For example, the selectivity towards Eis of chlorhexidine (6), normally non-selectively binding to negatively charged sites and therefore expected to inhibit AAC(2′), AAC(3), and AAC(6′), could be justified by the uniqueness of the Eis AG-binding site that could accommodate compound 6 in conformation(s) that the other AACs could not.

In sum, by using an in vitro high-throughput screening UV-Vis assay, we have identified 25 inhibitors of Eis from Mtb with 21 distinct scaffolds. The compounds display selective and potent inhibitory activity in vitro against the purified Mtb Eis and different modes of inhibition, with the known antibacterial chlorhexidine (6) competing with the AG for binding Eis. These findings provide the foundation for testing whether the Eis inhibitors will overcome KAN resistance in Mtb strains in which Eis is upregulated. This work also lays the groundwork for exploration of scaffold diversification and structure activity relationship studies of the identified biologically active compounds to be utilized in combination therapies with KAN or AMK against TB.

Experimental Section

Reagents and small-molecule libraries

All reagents including DTNB, NEO, KAN, AMK, and AcCoA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Eis was screened against 23,000 compounds from three diverse libraries of small molecules: (i) the BioFocus NCC library, (ii) the ChemDiv library (20,000 compounds), and (iii) the MicroSource MS2000 library composed of ∼2000 bioactive compounds (343 molecules with reported biological activities, 629 natural products, 958 known therapeutics, and 70 compounds approved for agricultural use). The activity of promising compounds was confirmed using repurchased samples from Sigma-Aldrich (compound 6) and ChemDiv (San Diego, CA) (compounds 4, 5, and 7-28).

Expression and purification of Eis and other AAC proteins

The Eis and AAC(2′)-Ic from Mtb,[21] as well as the AAC(3)-IV from E. coli[22, 39] and AAC(6′)/APH(2″)-Ia from S. aureus[22, 40] were overexpressed and purified as previously described.

Eis chemical library screening

The inhibition of Eis activity was determined by a UV-Vis assay monitoring the increase in absorbance at 412 nm (ε412 = 13,600 M−1cm−1) resulting from the reaction of DTNB with the CoA-SH released upon acetylation of NEO. The final reaction mixtures (40 μL) contained Eis (0.25 μM), NEO (100 μM), Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.0 adjusted at rt), AcCoA (40 μM), DTNB (0.5 mM), and the potential inhibitors (20 μM). Positive and negative control experiments were performed using chlorhexidine (6) (5 μM) and DMSO (0.5% v/v), respectively, instead of the potential inhibitors. Briefly, a mixture (30 μL) containing Eis (0.33 μM) and NEO (133.33 μM) in Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.0 adjusted at rt) was added to 384-well non-binding-surface plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) using a Multidrop dispenser (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The potential inhibitors (0.2 μL of a 4 mM stock), chlorhexidine (6) (0.2 μL of a 1 mM stock), or DMSO (0.2 μL) were then added to each well by Biomek HDR (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). After 10 min at rt, reactions were initiated by addition of a mixture (10 μL) containing AcCoA (160 μM), DTNB (2 mM), and Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.0 adjusted at rt). After an additional 5 min of incubation at rt, the absorbance was measured at 412 nm using a PHERAstar plate reader (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC). The average Z′ score for the entire high-throughput screening assay was 0.65.

Hit validation

Using the above conditions, all compounds deemed a hit (> 3σ as a statistical hit threshold from the mean negative control) were tested in triplicate. Compounds that displayed inhibition at least in 2 of the 3 independent assays were then tested for a dose-response using 2-fold dilutions from 20 μM to 78 nM. IC50 values were determined for all compounds displaying a dose-dependent activity.

Inhibition kinetics

IC50 values were determined on a multimode SpectraMax M5 plate reader using 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) by monitoring absorbance at 412 nm taking measurements every 30 s for 20 min. Eis inhibitors were dissolved in Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.0 adjusted at rt containing 10% v/v DMSO) (100 μL) and a 2- or 5-fold dilution was performed. To the solution of inhibitors, a mixture (50 μL) containing Eis (1 μM), NEO (400 μM), and Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.0 adjusted at rt) was added. After 10 min, the reactions were initiated by addition of a mixture (50 μL) containing AcCoA (2 mM), DTNB (2 mM), and Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.0 adjusted at rt). Overall, inhibitor concentrations ranged from 200 μM to 4 pM. Initial rates (first 2-5 min of reaction) were calculated and normalized to reactions containing DMSO only. All assays were performed at least in triplicate. IC50 values were calculated by using a Hill-plot fit with the KaleidaGraph 4.1 software. Two representative examples of IC50 curves are provided in Fig. 2, while the other 23 IC50 curves are presented in Fig. S1. Determination of IC50 values of compounds 4 and 6 against AMK and KAN were also performed as described above (Fig. S2). All IC50 values are listed in Table 1.

Mode of inhibition

By using the conditions described for inhibition kinetics with varying concentrations of NEO (50, 75, 100, 125, 150, and 200 μM) and compounds 4 (1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 μM) or 6 (5, 10, 20, and 40 nM), mixed inhibition was determined for compound 4 and compound 6 was found to be a competitive inhibitor of NEO. Resulting reaction rates were plotted as Lineweaver-Burk plots (Fig. 2 inserts of panels A and B). Using the same assay conditions, chlorhexidine (6) was also found to be a competitive inhibitor of KAN and AMK.

Inhibitors' selectivity for Eis

In order to establish if the identified inhibitors are selective for Eis, we tested the four best Eis inhibitors (4, 6, 7, and 8) with three other AACs: AAC(2′)-Ic, AAC(3)-IV, and AAC(6′)/APH(2″)-Ia. The conditions described for inhibition kinetics were used with varying concentrations of compounds 4, 6, 7, or 8 (200 to 0.2 μM, 10-fold serial dilution) and AAC(2′)-Ic (0.125 μM), AAC(3)-IV (0.25 μM), or AAC(6′)/APH(2″)-Ia (0.25 μM) instead of Eis. For AAC(2′)-Ic with compound 4, the concentration of inhibitor ranged from 1 μM to 500 pM and a 5-fold serial dilution was used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Life Sciences Institute, the College of Pharmacy, a Center for Chemical Genomics (CCG) Pilot Grant at the University of Michigan (S.G.T.), and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant AI090048 (S.G.T.). We thank Martha J. Larsen, Steve van de Roest, and Thomas J. McQuade (CCG, University of Michigan) for their help with HTS. We thank Oleg V. Tsodikov for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chembiochem.org.

References

- 1.Dye C, Williams BG. Science. 2010;328:856. doi: 10.1126/science.1185449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koul A, Arnoult E, Lounis N, Guillemont J, Andries K. Nature. 2011;469:483. doi: 10.1038/nature09657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry CE, 3rd, Blanchard JS. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:456. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houghton JL, Green KD, Chen W, Garneau-Tsodikova S. Chembiochem. 2010;11:880. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yew WW, Lange C, Leung CC. Eur Respir J. 2010;37:441. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00033010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green KD, Chen W, Garneau-Tsodikova S. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00312-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. Drug Resist Updat. 2010;13:151. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shcherbakov D, Akbergenov R, Matt T, Sander P, Andersson DI, Bottger EC. Mol Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jugheli L, Bzekalava N, de Rijk P, Fissette K, Portaels F, Rigouts L. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5064. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00851-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Yew WW. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell PJ, Morlock GP, Sikes RD, Dalton TL, Metchock B, Starks AM, Hooks DP, Cowan LS, Plikaytis BB, Posey JE. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2032. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01550-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaunbrecher MA, Sikes RD, Jr, Metchock B, Shinnick TM, Posey JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907925106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin DM, Jeon BY, Lee HM, Jin HS, Yuk JM, Song CH, Lee SH, Lee ZW, Cho SN, Kim JM, Friedman RL, Jo EK. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001230. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahl JL, Wei J, Moulder JW, Laal S, Friedman RL. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4295. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4295-4302.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahl JL, Arora K, Boshoff HI, Whiteford DC, Pacheco SA, Walsh OJ, Lau Bonilla D, Davis WB, Garza AG. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2439. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2439-2447.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu S, Barnes PF, Samten B, Pang X, Rodrigue S, Ghanny S, Soteropoulos P, Gaudreau L, Howard ST. Microbiology. 2009;155:1272. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.024638-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei J, Dahl JL, Moulder JW, Roberts EA, O'Gaora P, Young DB, Friedman RL. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:377. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.377-384.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lella RK, Sharma C. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts EA, Clark A, McBeth S, Friedman RL. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5410. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5410-5417.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuel LP, Song CH, Wei J, Roberts EA, Dahl JL, Barry CE, 3rd, Jo EK, Friedman RL. Microbiology. 2007;153:529. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/002642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen W, Biswas T, Porter VR, Tsodikov OV, Garneau-Tsodikova S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105379108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green KD, Chen W, Houghton JL, Fridman M, Garneau-Tsodikova S. Chembiochem. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaul P, Green KD, Rutenberg R, Kramer M, Berkov-Zrihen Y, Breiner-Goldstein E, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Fridman M. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:4057. doi: 10.1039/c0ob01133a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE, 3rd, Blanchard JS. Science. 2009;323:1215. doi: 10.1126/science.1167498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoffels K, Traore H, Vanderbist F, Fauville-Dufaux M. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ejim L, Farha MA, Falconer SB, Wildenhain J, Coombes BK, Tyers M, Brown ED, Wright GD. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:348. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu K, Lu H, Hou L, Qi Z, Teixeira C, Barbault F, Fan BT, Liu S, Jiang S, Xie L. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7843. doi: 10.1021/jm800869t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teixeira C, Barbault F, Rebehmed J, Liu K, Xie L, Lu H, Jiang S, Fan B, Maurel F. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:3039. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Lu H, Zhu Q, Jiang S, Liao Y. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:189. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D. S. Goldfarb, University of Rochester, U.S.A., 2009, p. 57pp

- 31.Schepetkin IA, Khlebnikov AI, Kirpotina LN, Quinn MT. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5232. doi: 10.1021/jm0605132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin H, Shi J, Noberini R, Pasquale EB, Song J. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804114200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominianni SJ, Yen TT. J Med Chem. 1989;32:2301. doi: 10.1021/jm00130a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saravia ME, Nelson-Filho P, Ito IY, da Silva LA, da Silva RA, Emilson CG. Microbiol Res. 2010;166:63. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xue Y, Zhang S, Yang Y, Lu M, Wang Y, Zhang T, Tang M, Takeshita H. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0960327111400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vetting MW, Hegde SS, Javid-Majd F, Blanchard JS, Roderick SL. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:653. doi: 10.1038/nsb830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolf E, Vassilev A, Makino Y, Sali A, Nakatani Y, Burley SK. Cell. 1998;94:439. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vetting MW, Park CH, Hegde SS, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC, Blanchard JS. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9825. doi: 10.1021/bi800664x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magalhaes ML, Blanchard JS. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16275. doi: 10.1021/bi051777d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boehr DD, Daigle DM, Wright GD. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9846. doi: 10.1021/bi049135y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.