Abstract

Context:

Patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease (cCHD) are prone to develop frequent brain abscesses. Surgery for these abscesses is often limited to aspiration under local anesthesia because excision under general anesthesia (GA) is considered a riskier option. Perioperative hemodynamic instability, cyanotic spells, coagulation defects, electrolyte and acid base imbalance, and sudden cardiac arrest are among the major anesthetic concerns. Most of our current knowledge in this area has been gained from a neurosurgical standpoint while there is a paucity of corresponding anesthesia literature.

Aims:

To highlight the anesthesia issues involved in cCHD children undergoing brain abscess excision under GA.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective study of our institutional experience over a 5 year period.

Materials and Methods:

Of all the children with cCHD who underwent brain abscess surgery from January 2005 to December 2009, only 4 were operated under GA. Surgery was done after correcting fever, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, coagulopathy and acid-base abnormalities, and taking appropriate intraoperative steps to maintain hemodynamic stability and prevent cyanotic spells and arrhythmias. Results: All 4 patients had a successful abscess excision though with varying degrees of intraoperative problems. There was one death, on postoperative day 34, due to septicemia. Conclusions: Brain abscess excision under GA in children of cCHD can be safely carried out with proper planning and attention to detail.

Keywords: Anesthesia, brain abscess, children, cyanotic heart disease, intracranial surgery

Introduction

Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease (cCHD) is characterized by intracardiac right-to-left shunting of unsaturated blood and its distribution into the systemic circulation resulting in arterial hypoxemia. Patients with cCHD develop repeated brain abscesses secondary to polycythemia-induced cerebral infarcts; further, poor host immunity and bypass of lung phagocytosis are contributory factors. cCHD, especially Tetrology of Fallot (TOF), accounts for nearly 13-70% of all brain abscess cases.[1,2] Management of a usual brain abscess includes either aspiration by various techniques and 6-8 weeks of antibiotics or craniotomy and excision in abscesses unresponsive to antibiotics, in large and superficial abscesses in non-eloquent brain regions causing significant mass effect and neurological deficits, and in multi-loculated abscesses.[3,4] In patients with cCHD, however, the choice of surgery is also influenced, to a large extent, by their preoperative state and ability to handle general anesthesia (GA). Presence of a fragile cardiopulmonary status and various systemic and coagulation complications, together with abscess-induced problems such as raised intracranial pressure (ICP), seizures, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and meningitis make cCHD patients high-risk candidates for abscess excision under GA. Hence, in these patients, treatment of an abscess is often limited to aspiration under local anesthesia (LA); further, repeated aspirations are continued even when excision is clearly indicated.[3,4] However, GA with controlled ventilation benefits small, uncooperative children and those with a high ICP, seizures, congestive cardiac failure (CCF), hemodynamic instability, and history of frequent cyanotic spells; it is thus imperative to be familiar with the anesthesia practices in patients with cCHD. While sufficient literature exists discussing the neurosurgical aspects of brain abscesses in cCHD patients, none addresses the anesthetic issues.[1,2,5,6] We present here our experience in anesthetising children with cCHD for brain abscess surgery and discuss the relevant medical literature.

Materials and Methods

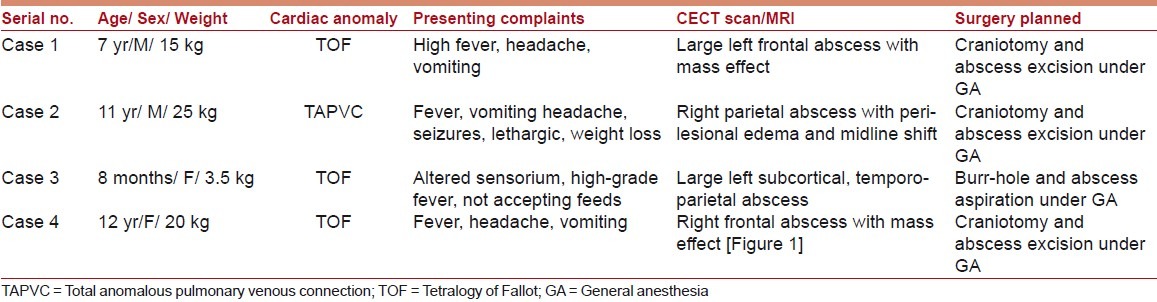

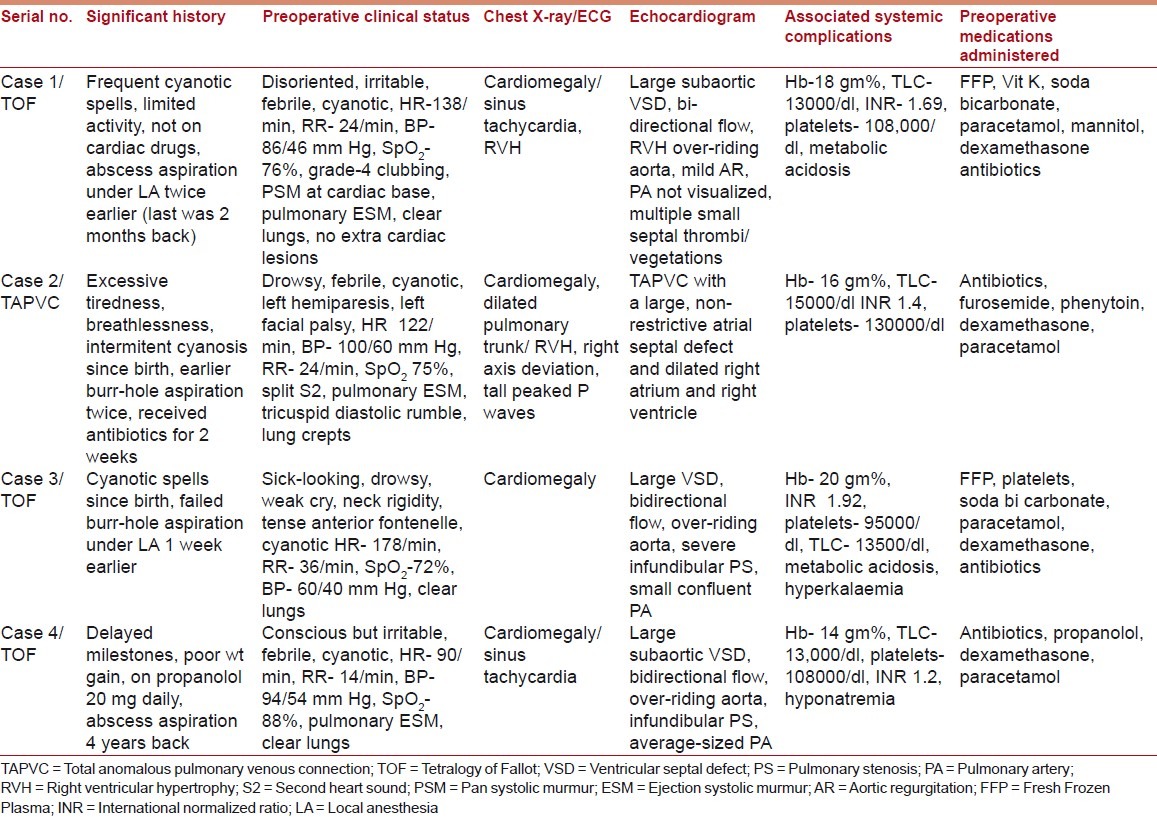

Between January 2005 and December 2009, several patients with cCHD were managed surgically for brain abscesses at our institute, but only four children received GA; Tables 1 and 2 present their preoperative data.

Table 1.

Preoperative data

Table 2.

Preoperative data

Emergency surgery was undertaken with a high-risk consent. Fever, coagulopathy, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and metabolic acidosis were corrected prior to surgery, where possible. Preparations before anesthesia included readying inotropes/vasopressors, administering prophylactic antibiotics, and de-airing of all intravenous (IV) lines. Intravenous fentanyl (2-4 μg/kg), midazolam (0.5-1 mg), atracurium (0.5 mg/kg and 5 μg/kg/min infusion), and sevoflurane/isoflurane inhalation were used for anesthesia, and ventilation was controlled. Besides routine monitors, invasive arterial blood pressure (ABP), central venous pressure (CVP), and arterial blood gases were monitored. Isotonic fluid therapy was CVP-guided; Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) and platelets were transfused as indicated. Postoperatively, the children were intensively monitored for 4-5 days.

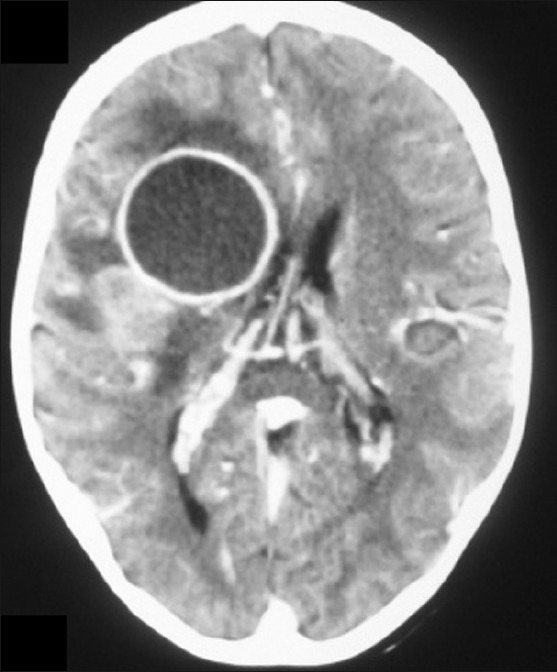

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan showing a large ring-enhancing lesion in the posterior frontal region with mass effect

Results

Cases 1, 2, and 4 were hemodynamically stable and without major complications during surgery. Metabolic acidosis was corrected in all children and hyponatremia in Case 1; FFP was transfused in Cases 1 and 2. Case 1 suffered repeated postoperative cyanotic spells with exaggerated cyanosis, decrease in oxygen saturation (SpO2) to 41%, decrease in ABP to 58/33 mm Hg, and increase in Heart Rate (HR) to 162 beats/ min; he was treated with 100% O2, IV boluses of morphine (1.5 mg) and propranolol (2.5 mg), soda bicarbonate, and rapid fluids. The spells stopped after regular propranolol therapy was started. Case 2 had repeated postoperative seizures and had to be re-ventilated for 48 hours; his seizures persisted, though less frequently. All three patients had gradual neurological recovery and were subsequently transferred to cardiology. For Case 3, dopamine infusion (7 μg/kg) was started before inducing anesthesia; during surgery, she had stable ABP and SpO2, but persistent tachycardia (HR 170-180 beats/min). Paracetamol, FFP, and soda bicarbonate were repeated. She was ventilated postoperatively and dopamine was replaced with noradrenaline infusion (0.025 μg/kg/min). Following extubation after 2 days, she was hemodynamically stable; however, the child developed septicemia and died after 34 days. Blood loss in all four children was within acceptable limits, and none received blood transfusion.

Discussion

Anesthetizing children with cCHD and a brain abscess is a major challenge necessitating the use of an anesthesia regimen appropriate to both cCHD and intracranial surgery.

Patients with cCHD suffer from the ill-effects of chronic hypoxemia; this usually manifests as persistent breathlessness and tiredness, repeated chest infections and fever, growth retardation, delayed milestones, severe metabolic derangements, multi-organ failure, and major neurological deficits secondary to a vascular stroke or brain abscess. A deficiency of vitamin K–dependent clotting factors, decreased and defective platelets, and accelerated fibrinolysis results in abnormal hemostasis with frequent and increased bleeding; the presence of CCF, arrhythmias, heart blocks, and infective endocarditis can cause severe hemodynamic instability. cCHD patients also have recurring bouts of severe cyanosis and hypoxemia, known as cyanotic spells, which can lead to convulsions, syncope, stroke, and death; spells are triggered by a heightened sympathetic activity during crying, agitation, or fright and results in increased right-to-left shunting. It manifests as abrupt worsening of cyanosis, tachycardia, hypotension, and tachypnea, and is treated with sedation (subcutaneous morphine 0.1-0.2 mg/ kg or intramuscular ketamine 1-3 mg/kg), phenylephrine (0.1 mg/ kg IV, 0.1-0.5 μg/kg/min infusion), propranolol (0.05–0.25 mg/ kg IV), soda bicarbonate, oxygenation, rapid IV fluids, and, if needed, controlled ventilation and emergency palliative Blalock-Taussig shunt surgery.[7,8]

Anesthesia for cCHD children begins with a thorough pre-anesthesia check-up documenting their current cardiac and neurological status, associated complications, history of prior abscess surgeries and palliative cardiac shunt surgeries, and current medications. A cardiology consultation, Two-Dimensional (2D)-echocardiography and assessment of coagulation profile are necessary. Vomiting, fever, poor oral intake, and diuretic use due to the brain abscess can cause dehydration and exaggeration of cCHD-induced blood hyperviscosity. Prolonged preoperative fasting should be avoided and drinking of clear fluids up to 2 hours before surgery encouraged; also, mannitol should be used cautiously. Severely cyanotic patients with hematocrit ≥60% may develop coagulopathy and benefit from preoperative phlebotomy. Gentle separation of children from their parents and avoidance of unnecessary pin-pricks can prevent excessive crying and precipitation of cyanotic spells. Intraoperative goals include maintenance of hemodynamic stability and oxygenation and prevention of cyanotic spells and arrhythmias. GA drugs must be titrated and administered slowly; ketamine is the ideal drug, but should be avoided in intracranial surgery; a high opioid–low benzodiazepine combination or sevoflurane/isoflurane can be used. Respiratory abnormalities warrant the use of controlled ventilation; ABG monitoring is essential since pulse oximetry is less accurate in severe cyanosis. The allowable blood loss is more in cCHD patients due to pre-existing polycythemia; transfusion is deferred till ≥25% of blood volume is lost. Air entry into veins should be prevented as it can cause life-threatening paradoxical embolism; for this, air filters in IV lines are useful. Hypotension, hypovolemia, acidosis, hypoxia, and hypercarbia increase intraoperative shunting and should be avoided; early extubation is preferred to prevent further reduction in pulmonary blood flow due to prolonged ventilation. Postoperative care includes intensive monitoring, appropriate fluid management, and good control of pain.[7,8]

A higher risk of perioperative complications and cardiac arrest, and 30-day mortality is reported in children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD), especially cCHD, undergoing non-cardiac surgery as compared to the normal population.[9] Patients below 2 years of age, those undergoing emergency surgery, and those having severe cyanosis, poorly compensated CCF, and major cardiac anomalies are particularly at risk.[10] A significantly higher mortality has also been reported in cCHD patients during brain abscess aspirations, attributed variously to cyanotic spells[2] and to a greater midline shift and cerebral edema;[6] moreover, surgery under LA is likely to exaggerate both these conditions due to the accompanying anxiety, pain, and excessive crying. A carefully administered GA with controlled ventilation, advanced monitoring, and better preparedness for handling emergencies facilitates a safer environment for maintenance of hemodynamics, oxygenation, and ICP and seizure control, as is highlighted by the safe anesthetic outcome of our patients. With more experience, the perioperative complication rate in patients with cCHD undergoing brain abscess surgery is likely to decline further.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ghafoor T, Amin MU. Multiple brain abscesses in a child with congenital cyanotic heart disease. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:603–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prusty GK. Brain abscesses in cyanotic heart disease. Indian J Pediatr. 1993;60:43–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02860506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma BS, Gupta SK, Khosla VK. Current concepts in the management of pyogenic brain abscess. Neurol India. 2000;48:105–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moorthy RK, Rajshekhar V. Management of brain abscess: an overview. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E3. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/6/E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeshita M, Kagawa M, Yato S, Izawa M, Onda H, Takakura K, et al. Current treatment of brain abscess in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1270–9. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atiq M, Ahmed US, Allana SS, Chishti NK. Clinical features and outcome of cerebral abscess in congenital heart disease. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2006;18:21–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yumul R, Emdadi A, Nassim M. Anesthesia for non cardiac surgery in children with congenital heart disease. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;7:153–65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.White MC. Anaesthetic implications of congenital heart disease for children undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care Med. 2009;10:504–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flick RP, Sprung J, Harrison TE, Gleich SJ, Schroeder DR, Hanson AC, et al. Perioperative cardiac arrests in children between 1988 and 2005 at a tertiary referral center: A study of 92 881 patients. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:226–37. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baum VC, Barton DM, Gutgesell HP. Influence of congenital heart disease on mortality after noncardiac surgery in hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2000;105:332–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]