Abstract

Iron deficiency anemia is a common pediatric problem affecting up to 25% children worldwide. It has been linked with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in the literature. We describe a 9-month-old child who had severe iron deficiency anemia and developed acute venous sinus thrombosis associated with minor infection. Treatment with anticoagulation was partially successful with persistent thrombosis after 3 months. We reviewed the current literature highlighting the association of anemia as a risk factor for development of stroke in children.

Keywords: Anemia, children, stroke, venous sinus thrombosis

Introduction

Cerebro-vascular diseases are one of the top 10 causes of mortality and morbidity in children.[1] Current figures suggest the incidence of 2–5/100,000 children/year for childhood stroke and at least 300 children in the United Kingdom are diagnosed with stroke per year. Cerebral sino-venous thrombosis (CSVT) is a rare but serious cause of stroke in children. The diagnosis is often delayed as clinical presentation is varied and nonspecific. Children can present with headaches, encephalopathy, seizures or increased intracranial pressure. Various risk factors have been identified in the literature including dehydration, sepsis, inflammatory diseases, and prothrombotic factors.[2]

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a common pediatric problem affecting up to 25% of all the children worldwide.[3] In an American survey 9% of children 1-2 years of age, 3% of children 3--5 years of age, and 2% of children 6-11 years of age were found to be iron deficient.[4] It has been reported as a direct underlying causative factor leading to CVST. We report an infant who presented with severe anemia and developed CSVT. We also review the current literature and postulated mechanisms between anemia and CSVT.

Case Report

A young nine-month-old boy of Asian origin presented to our hospital with 1 day history of mild temperature, vomiting, and coryzal symptoms. He was born out of nonconsanguineous marriage and is the only child of his parents. He had a normal birth and development, and was up to date with his immunizations. There was no family history of any serious neurological conditions or strokes. On initial examination his temperature was 38.5°C and heart rate of 100 beats per minute. Hydration was normal. He was noted to be very pale and had a systolic murmur over the precordium. Liver was 1 cm below the costal margin with no other masses palpable.

Laboratory investigations showed that his hemoglobin (Hb) was 4.1 g/l, platelets 866, white cell count 14, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 48, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) 11, reticulocyte count 22, and total iron of 7 μg/l. Liver functions, renal profile, and C reactive protein were normal. His urine was clear. Chest X ray was unremarkable with no cardiomegaly. Blood film demonstrated severe microcytosis and “pencil cells.” Hemoglobin electrophoresis showed Hb A2 of 2.2% and Hb F 1.7%.

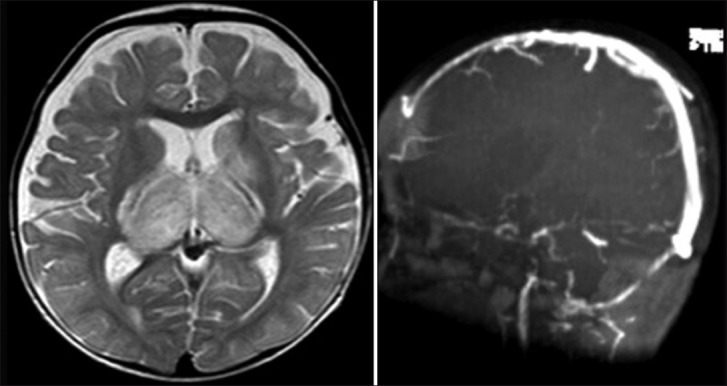

Child was admitted due to severe anemia and started on oral Iron. He developed mild diarrhea over the next few days which completely settled. Blood transfusion was not required and he was never unwell or in cardiac failure. After 7 days of hospitalization, he suddenly became drowsy and encephalopathic with GCS of 9/15. Urgent CT scan of his brain showed extensive cerebral sinus thrombosis with venous infarction. MRI brain demonstrated bilateral thalamic infarction with hemorrhagic transformation. MR Venogram (MRV) confirmed extensive thrombosis of internal cerebral vein, vein of Galen, straight sinus, sigmoid sinus, and basal vein of Rosenthal [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging and MR Venogram done after the acute illness demonstrating bilateral thalamic infarction with hemorrhagic transformation and extensive venous sinus thrombosis

He was started on low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). He later developed mild left hemiparesis which resolved within days. Repeat CT brain did not show any extension or new hemorrhage. Cardiac echogram was normal. He remained well and was discharged from the hospital with no focal deficit.

Repeat MRI after 3 months showed partial recanalization of venous sinuses. Neurologically he has remained well and his development is normal. Extensive investigations to determine any other underlying prothrombotic disorder were negative.

Discussion

Iron is considered to be important for normal neurodevelopment. IDA has been linked with various neurological complications like motor developmental delay, behavioural problems, breath holding spells, stroke, pseudotumor cerebri and cranial nerve palsies.[5] IDA has also been associated with CSVT as described in some case reports and case series in the pediatric literature.[6,7] Hartfield et al.[1] described six children aged between 6 and 18 months, who developed stroke with anemia. Three children developed CSVT, and the other three had an arterial stroke. All children had preceding mild viral infection of either the upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract.

In a case control study by Maguire et al.,[8] anemia was significantly more common in children with stroke than in controls (53% vs. 9%). Previously healthy children who developed vaso-occlusive stroke are 10 times more likely to have IDA than healthy children, who do not develop stroke. They also noted a stronger association of CSVT with IDA than arterial ischemic stroke.

Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association between iron deficiency and CSVT. Serum iron is an important regulator of thrombopoiesis.[9] Normal iron levels are required to prevent thrombocytosis by acting as an inhibitor. Iron deficiency can increase the number of platelets in blood, which is linked with a hypercoagulable state. However reactive thrombosis is often benign in children as compared to adults.[6] Erythropoietin which stimulates megakaryocytes is also increased during the iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency in itself can lead to a hypercoagulable state. It has been found that microcytosis decreases the cell deformability and increase the viscosity, causing abnormal flow patterns.[10] Under conditions of stress or infections, the metabolic demand at the tissue level rises which can create anemic hypoxia and can predispose to venous thrombosis.[11]

Our child had severe IDA at presentation with symptoms of mild viral infection. He developed some diarrhea and vomiting but was never clinically dehydrated. Mild thrombocytosis was noted, which is often expected in iron deficiency. No other predisposing factors for CSVT were present like sepsis, trauma, autoimmune diseases or prothrombotic disorders.

CT venography or MRI with MRV is the preferred imaging modalities for investigating CSVT. Management of CSVT involves anticoagulation therapy (ACT) and symptomatic measures such as hydration, antimicrobials, control of seizures with anticonvulsants and management of raised intracranial pressure. The aim of ACT is to recanalyze and to prevent further spread of thrombus. Unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is recommended in the absence of any major hemorrhage in older children, except in neonates.[2,12] Duration of therapy depends on an underlying condition and patency of venous sinuses. Repeat venous imaging is recommended after 3 months to evaluate for recanalization and resolution of clot. If fully recanalized, ACT can be discontinued. If venous sinuses are partially recanalized, treatment should be continued for at least 6 months. Thrombolysis, thrombectomy or surgical decompression has only been used in isolated cases in seriously ill patients or in those with worsening thrombosis despite adequate anticoagulation. In the study by Kenet et al., recurrence rate of CSVT in children was found to be 6%.[13] The predictors of recurrent thromboses included persistent occlusion on follow-up venous imaging, heterozygosity for the G20210A mutation in factor II and the lack of anticoagulant therapy.

IDA in children may not be benign as previously thought. Children with severe IDA should be actively treated and monitored, especially during minor infections because of the risk for developing CSVT. LMWH should be considered for the treatment in the absence of any contraindications.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Hartfield DS, Lowry NJ, Keene DL, Yager JY. Iron deficiency: A cause of stroke in infants and children. Pediatr Neurol. 1997;16:50–3. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(96)00290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes C, Newall F, Furmedge J, Mackay M, Monagle P. Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40:53–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozoff B, Jimenez E, Wolf AW. Long-term developmental outcome of infants with iron deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:687–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109053251004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Looker AC, Dallman PR, Carroll MD, Gunter MT, Johnson CL. Prevalence of iron deficiency in the United States. JAMA. 1997;277:973–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540360041028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yager JY, Hartfield DS. Neurologic manifestations of iron deficiency in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 2002;27:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(02)00417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belman AL, Roque CT, Ancona R, Anand AK, Davis RP. Cerebral venous thrombosis in a child with iron deficiency anemia and thrombocytosis. Stroke. 1990;21:488–93. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedict SL, Bonkowsky JL, Thompson JA, Van Orman CB, Boyer RS, Bale JF, Jr, et al. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in children: Another reason to treat iron deficiency anemia. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:526–31. doi: 10.1177/08830738040190070901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire JL, deVeber G, Parkin PC. Association between iron-deficiency anemia and stroke in young children. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1053–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruggers CS, Ware R, Altman AJ, Rourk MH, Vedanarayanan V, Chaffee S. Reversible focal neurologic deficits in severe iron deficiency anemia. J Pediatr. 1990;117:430–2. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold DW, Gulati SC. Myeloproliferative Diseases. In: Isselbacher KJ, Braunwald E, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison's Internal Medicine. 13th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 1994. pp. 1757–64. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keane S, Gallagher A, Ackroyd S, McShane MA, Edge JA. Cerebral venous thrombosis during diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:204–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson MC, Parkerson N, Ward S, de Alarcon PA. Pediatric sinovenous thrombosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:312–5. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenet G, Kirkham F, Niederstadt T, Heinecke A, Saunders D, Stoll M, et al. Risk factors for recurrent venous thromboembolism in the European collaborative paediatric database on cerebral venous thrombosis: A multicentre cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:595–603. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70131-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]