Abstract

Cavernous hemangioma (CH) is a sporadic vascular malformation occurring either as an autosomal dominant condition or as a well-known complication of radiation exposure. Medulloblastoma is a primitive neuroectodermal tumor common in children and currently treated with surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Neurofibromatosis is the most common single-gene disorder of the central nervous system. Posterior fossa malignant tumors in the context of neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) are very infrequent. This is the first documented case of an unusual metachronous occurrence of non-radiation-induced CH and medulloblastoma in a child with NF1 phenotype. We report the case of a 13-month-old boy with café-au-lait skin lesions associated with NF1-like phenotype who underwent surgical resection of a single CH in the temporal lobe due to recurrent seizures. Four years later he presented with signs of raised intracranial pressure associated with a posterior fossa tumor and hydrocephalus, thus requiring gross total resection of the lesion. Histological analysis revealed a medulloblastoma. After being treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, he achieved total remission. Six years later a massive recurrence of the tumor was observed and the child eventually died. The interest in this case lies in the rarity of NF1-like phenotype associated with a non-radiation-induced brain CH and medulloblastoma in a child.

Keywords: Cavernous hemangioma, medulloblastoma, neurofibromatosis type1, pediatric neurosurgery, radiation therapy

Introduction

Cavernous hemangiomas (CH) are well-defined lesions composed of closely packed sinusoidal vascular channels with structurally incomplete vessel walls and no intervening neuronal parenchyma.[1] Although cavernous malformations are thought to arise sporadically in many individuals, a substantial number of patients have been characterized with a heritable form of this disease, which is transmitted in an autosomal-dominant mode, with variable expression and incomplete penetrance, often presenting as multiple intracranial lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[1,2] The de novo appearance of CH has been firmly established, most notably after radiation therapy. The lesions usually appear 8–10 years later within brain tissue that was included in radiation fields.[3,4]

In contrast to the infrequency of CH, medulloblastomas are the most common malignant brain tumors of the posterior cranial fossa in children, being generally associated with several familial cancer predisposition syndromes.[5–7] Although café-au-lait lesions occur with variable frequency in a number of disorders, such as neurofibromatosis types 1 (NF1) and 2, Albright syndrome, among others,[2,7] to the best of our knowledge this phenotype has never been reported before in association with a non-radiation-induced brain CH and medulloblastoma.

Case Report

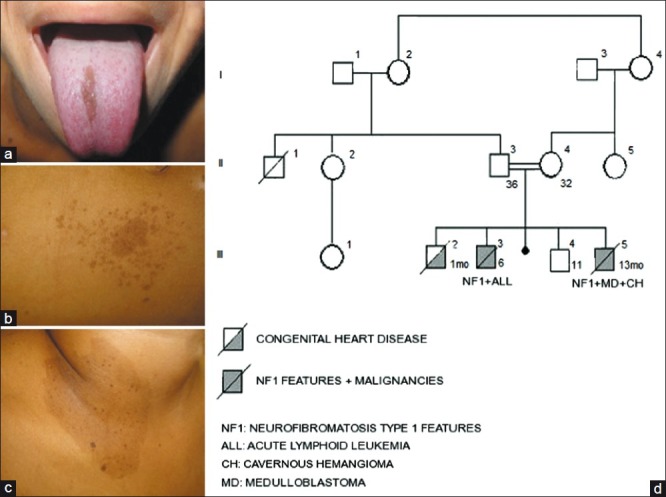

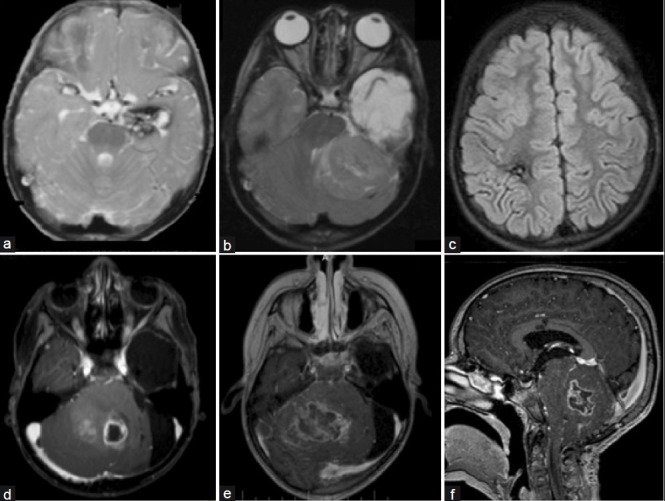

A 13-month-old boy, with consanguineous parents, was referred to the Pediatric Emergency Department of our hospital with partial-complex seizure. Clinical evaluation revealed normal neurological development and no focal deficits. No iris nevi or Lisch nodules were evident on ophthalmological examination. Prominent café-au-lait skin lesions were observed on the patient's neck and midchest [Figure 1a-c]. His father and brother had similar dermatologic signs, the latter having died at the age of 6 years due to T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia. He also had an older brother who died owing to congenital heart disease [Figure 1d]. MRI of the brain showed an isolated lesion in the left mesial-temporal lobe [Figure 2a]. Microsurgical total removal of the lesion was performed. Histological diagnosis confirmed a typical cavernous hemangioma. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged after four days. Outpatient consultations were performed routinely.

Figure 1.

(a) Lingual melanotic macule. (b, c) Café-au-lait lesions associated with multiple ephelides. (d) Pedigree of the family. The generations are indicated with roman numerals (I–III). Numbers on top of the symbols indicate the individuals in each generation. Squares, male; circles, female; symbols with a diagonal, deceased individuals. Age at diagnosis is indicated on the right bottom of the symbols. Solid symbols, affected individuals; shaded symbol with a diagonal, congenital heart disease

Figure 2.

(a) Axial T2-weighted Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing the left mesial temporal cavernous hemangioma. (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI showing a left-cerebellar posterior fossa tumor with brainstem displacement. (c) Fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery image showing an asymptomatic right frontal radiationinduced cavernous hemangioma 60 months after radiation terapy; (d) Axial T1-weighted MRI enhanced with gadolinium showing recurrence of the medulloblastoma in the cerebellar vermis. (e, f) Axial and sagittal T1-weighted image enhanced with gadolinium two months later showing massive brain stem infiltration

At the age of 4 years he presented with a 7-day history of progressively worsening headache, vomiting, and gait ataxia. Ophthalmological evaluation revealed papilledema. MRI scans showed supratentorial hydrocephalus associated with a posterior fossa tumor in the left cerebellar hemisphere displacing the brainstem [Figure 2b]. Thorough neuroimaging screening of the neuroaxis showed no other lesions at that time. Gross total resection was achieved by suboccipital craniotomy. Histological examination of the tumor revealed a nodular medulloblastoma grade IV (WHO). The patient underwent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Five years later, control MRI scans confirmed no recurrence of the lesion, however showed multiple and asymptomatic radiation-induced cavernous hemangiomas [Figure 2c]. At the age of 10 a massive recurrence of the medulloblastoma was observed in the posterior fossa associated with severe hydrocephalus [Figure 2d]. Initially, an endoscopic third ventriculostomy was performed uneventfully. A surgical resection was attempted with the aim of reducing the lesion. In spite of aggressive adjuvant treatment, the child died 3 months later due to infiltration of adjacent brain stem and clinical complications [Figure 2e, f].

Discussion

Café-au-lait skin lesions are more commonly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), or von Recklinghausen syndrome. The presence of six or more large skin lesions with diameters above 1.5 cm is considered to be virtually diagnostic of NF1.[2] Our patient fulfilled this criterion, with more than a dozen large café-au-lait skin lesions in addition to numerous ephelides on the neck, midchest and armpits. Although various skin lesions have been reported in association with familial CH, documented cases of café-au-lait lesions are scarce.[6,2]

Recent publications have documented the de novo formation of CH following radiation treatment.[3,4,8,9] Venous restrictive disease has been postulated to be a consequence of impaired venous flow caused by radiation change. This impairment increases venous pressure and may lead to the formation of cavernous hemangioma.[4] A cumulative increase of radiation-induced CH occurs over time in children who receive cranial radiation therapy. In our case, the CH diagnosed in the mesial temporal lobe was obviously not related to radiation.

Posterior fossa tumors associated with NF1 are very infrequent,[7,10,11,12] differently from those tumors located in other regions, such as optic pathway tumors and brain stem tumors, which are common and histologically benign.[13] Therefore, medulloblastoma is a typically malignant cerebellar tumor of infancy rarely associated with NF1 clinical features.

In view of these facts, our case has been extensively analyzed in order to define a syndrome that could explain the presence of NF1 clinical features associated with non-radiation-induced brain CH and posterior fossa medulloblastoma in a child with consanguineous parents. Therefore, the Department of Genetics of our university has investigated whether the patient's presentation was related to constitutional mismatch repair-deficiency (CMMR-D).

The mismatch repair (MMR) machinery contributes to genome integrity, and the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 genes play a crucial role in this process. MMR corrects single base-pair mismatches and small insertion-deletion loops that arise during replication.[14,15] Moreover, the MMR system is involved in the cellular response to a variety of agents that damage DNA, as well as in immunoglobulin class switch recombination.[16]

Heterozygous germline mutations may cause Lynch syndrome, an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, endometrial carcinoma, and other malignancies, generally occurring in the fourth and fifth decade of life.[15] In contrast, rare cases of biallelic deleterious germline mutations in MMR genes leading to CMMR-D have been recognized since 1999.[17,18] This cancer syndrome is characterized by a wide spectrum of early-onset malignancies such as hematological, brain or gastrointestinal cancers and a phenotype that resembles NF1.[19] Interestingly, several reports stress that café-au-lait macules differ from typical NF1-associated lesions in that they have variable degree of pigmentation, irregular borders, and, usually, a segmental distribution pattern.[14] Other features of NF1 found in CMMR-D patients include Lisch nodules, neurofibromas, skinfold freckling, and tibial pseudarthrosis. Hence, it is not surprising that a number of CMMR-D cases were initially diagnosed as NF1.[14,15] It has been speculated that NF1-like clinical features in CMMR-D patients result from germline mosaicism arising early during embryonic development.

There are data supporting the hypothesis that the NF1 gene is a mutational target of MMR deficiency.[20] The diagnosis of this deficiency should be confirmed by gene-specific mutation analysis. The use of such analysis may facilitate identification and surveillance of heterozygous and homozygous individuals in the wider family, in addition to allowing for informed decision-making about prenatal genetic diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Clarissa Picanço, M.D., for her assistance in genetic analysis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Moriarity JL, Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D. The natural history of cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1999;10:411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musunuru K, Hillard VH, Murali R. Widespread central nervous system cavernous malformations associated with café-au-lait skin lesions. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:412–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.2.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumgartner JE, Ater JL, Ha CS, Kuttesch JF, Leeds NE, Fuller GN, et al. Pathologically proven cavernous angioma of the brain following radiation therapy for pediatric brain tumors. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;39:201–7. doi: 10.1159/000072472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lew SM, Morgan JN, Psaty E, Lefton DR, Allen JC, Abbott R. Cumulative incidence of radiation-induced cavernomas in long-term survivors of medulloblastoma. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:103–7. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.104.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banka S, Walsh R, Brundler MA. First report of occurrence of choroid plexus papilloma and medulloblastoma in the same patient. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:587–9. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. Familial tumour syndromes. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Lyon: IARC; 2007. pp. 205–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robles Cascallar P, Contra Gómez T, Martín Ramos N, Scaglione Ríos C, Madero López L. Association of neurofibromatosis type 1 and medulloblastoma. An Esp Pediatr. 1992;37:57–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeder P, Gudinchet F, Meuli R, de Tribolet N. Development of a cavernous malformation of the brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1141–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poussaint TY, Siffert J, Barnes PD, Pomeroy SL, Goumnerova LC, Anthony DC, et al. Hemorrhagic vasculopathy after treatment of central nervous system neoplasia in childhood: Diagnosis and follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:693–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corkill AGL, Ross CF. A case of neurofibromatosis complicated by medulloblastoma, neurogenic sarcoma and radiation-induced carcinoma of thyroid. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1969;32:43–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.32.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-lage JF, Salcedo C, Corral M, Poza M. Medulloblastomas in neurofibromatosis type 1.Case report and literature review. Neurocirurgia (Astur) 2002;13:128–31. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1473(02)70634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meadows AT, D’Angio GJ, Miké V, Banfi A, Harris C, Jenkin RD, et al. Pattern of second malignant neoplasms in children. Cancer. 1977;40:1903–11. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4+<1903::aid-cncr2820400822>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Viaño J, Carceller F, Gutierrez-Molina M, Morales C, et al. Posterior fossa tumors in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1599–603. doi: 10.1007/s00381-010-1163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wimmer K, Etzler J. Constitutional mismatch repair-deficiency syndrome: Have we so far seen only the tip of an iceberg? Hum Genet. 2008;124:105–22. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wimmer K, Kratz C. Constitutional mismatch repair-deficiency syndrome. Haematologica. 2010;95:699–701. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Péron S, Metin A, Gardès P, Alyanakian MA, Sheridan E, Kratz CP, et al. Human PMS2 deficiency is associated with impaired immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2465–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricciardone MD, Ozcelik T, Cevher B, Ozdag H, Tuncer M, Gurgey A, et al. Human MLH1 deficiency predisposes to hematological malignancy and neurofibromatosis type 1. Cancer Res. 1999;59:290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Q, Lasset C, Desseigne F, Frappaz D, Bergeron C, Navarro C, et al. Neurofibromatosis and early onset of cancers in hMLH1-deficient children. Cancer Res. 1999;59:294–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ripperger T, Beger C, Rahner N, Sykora KW, Bockmeyer CL, Lehmann U, et al. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency and childhood leukemia/lymphoma - report on a novel biallelic MSH6 mutation. Haematologica. 2010;95:841–4. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.015503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, Montmain G, Ruano E, Upadhyaya M, Dudley S, Liskay RM, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 gene as a mutational target in a mismatch repair-deficient cell type. Hum Genet. 2003;112:117–23. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0858-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]