Abstract

Ewing's sarcoma is a primary bone malignancy with the highest incidence in the second decade of life. Although it mostly affects the metaphyseal region of long growing bones, involvement of spine is not very uncommon especially the sacrum. Nonsacral spinal Ewing's sarcoma is rarer and often mimics a benign condition before spreading extensively. They present with neurologic deficits due to spinal cord compression, but acute onset paraplegia has not been previously reported. A high index of clinical suspicion can clinch the diagnosis early in the course of the disease. A prompt intervention is required to keep neurological damage to a minimum, and a correct combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy is required for better long-term patient outcome. We report a 16-year-old female who presented with acute paraplegia and had an excellent postoperative outcome after radical excision of a D9 Ewing's sarcoma.

Keywords: Ewing's sarcoma, paraplegia, primary spine tumor, spinal cord compression

Introduction

Primary malignant sarcomas of the spine are rare and they account for only 3.5%–14.9% of all primary bone sarcomas.[1] Ewing's sarcoma is the second most common primary bone tumor in pediatric patients accounting for approximately 4% of pediatric malignancies.[2] Its incidence is highest in the second decade of life and most commonly involves the long bones of the extremities and the pelvis, presenting primarily as swelling with pain. Primary vertebral Ewing's sarcoma has been divided into sacral and nonsacral types based on the differences in the treatment responses and survival rates.[3] Primary involvement of the nonsacral spine represents approximately 0.9% of all cases.[4] Low back pain is the most common symptom followed by a palpable swelling. Spinal cord compression can produce neurological deficits depending on the tumor location, but is often a delayed presentation. Rapidly progressing paraplegia is uncommon and a high index of suspicion is essential for diagnosis, especially in a young patient. We report a rare case of dorsal spine Ewing's sarcoma that presented with acute onset paraplegia and improved with radical tumor decompression.

Case Report

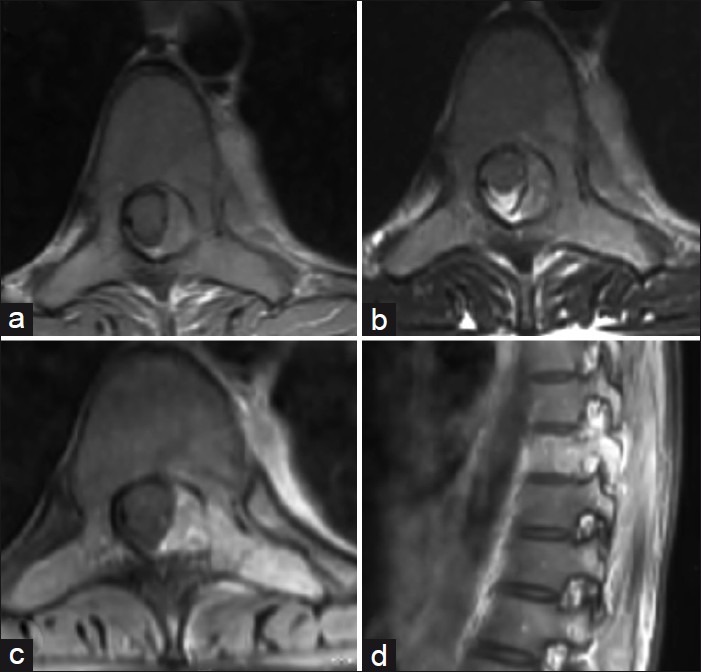

A 16-year-old female presented with a 2-week history of mild intermittent low back pain for which she was treated with analgesics at a local hospital. She presented to us with rapidly deteriorating weakness of both lower limbs over 24 hours. There was no antecedent history of trauma. No constitutional symptoms were present. On examination, there was bilateral spastic paraplegia with only a flicker of movement at the right ankle joint. Beevor's sign was positive and sensory examination revealed mild hypoesthesia to all sensations below the level of D10 dermatome. The muscle stretch reflexes of her lower extremities were exaggerated and Babinski response was extensor bilaterally. There was no evidence of any paraspinal tenderness or swelling. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a lesion in the D9 vertebra involving the body, pedicle, lamina, and the transverse process on the left side with an epidural soft tissue component compressing the spinal cord [Figure 1]. In view of the rapid progression of weakness, the patient was considered for emergency tumor decompression. Intraoperatively, the D9 lamina was eroded by the tumor and there was evidence of minimal paraspinal muscle involvement. The lesion was soft to firm in consistency and highly vascular. The extradural component of the tumor had displaced the cord to the right, but there was no evidence of any dural breach. The tumor was radically excised including the pedicle and part of the body which was involved. The neurological outcome of surgery was good with mild residual deficits. Strength and sensibility in the lower extremities gradually increased, and within 2 weeks after the surgery, the patient was ambulatory. She was referred for adjuvant systemic chemotherapy and local radiotherapy. Histopathology report was suggestive of a small round blue cell tumor that was confirmed as Ewing's sarcoma by immunohistochemistry.

Figure 1.

Axial T1-weighted (a) and T2-weighted (b) magnetic resonance imaging at D9 level showing the lesion involving the left half of the vertebral body, pedicle, transverse process, and the lamina with an epidural component producing cord compression. Postgadolinium injection axial and sagittal T1-weighted images (c and d) show intense enhancement of the tumor. Note the enhancing component in the paraspinal thoracic region

Discussion

The complex neuromusculoskeletal development of the spine may account for a spectrum of malignant tumors with distinct biological behaviors. The differential diagnosis of a small round cell bone tumor includes Ewing's sarcoma, neuroblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone, malignant lymphoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Ewing's sarcoma mostly occurs in childhood when the bones are growing. It commonly affects the metaphyseal plates of long bones and rarely involves the spine where the most common location is the sacrum. Although there have been reports of nonsacral spinal involvement but these are rare.[5] Ewing's sarcoma is often a multifocal disease, and a proper prestaging workup including bone scan is required before institution of therapy and for follow-up.[6]

The expansile nature of the lesion makes local swelling and pain as the most common presentation in cases of long bone involvement. Systemic symptoms may also be present. Involvement of nonsacral spine usually presents with features of spinal cord compression which is often late in the course of disease. Presentation as acute paraplegia without significant localized pain and swelling has not been reported in the literature.

Early diagnosis and treatment in Ewing's sarcoma can result in favorable outcomes. The presence of benign musculoskeletal symptoms often leads to a delay in diagnosis with many patients being misdiagnosed and treated for disc disease. Unlike other malignant spinal lesions that cause progressive and continuous pain that increases with recumbency, in majority of nonsacral spinal Ewing's sarcoma pain is often intermittent, without nocturnal exacerbation.[7] This intermittent progression versus an expected rapid course is a reason for further delay in diagnosis. Thus, it is clear that diagnosis of nonsacral spinal Ewing's sarcoma will require a high index of suspicion. A detailed patient history and a careful physical examination supplemented by imaging are essential to minimize the delay.

When deciding about the treatment of Ewing's sarcoma of the mobile spine, the most important determinant is the presence of neurological deficits, which once present are often rapidly progressive. In such circumstances, only a prompt surgical decompression can provide maximum chance of recovery.[8] The approach is defined by the type of involvement. Anterior decompression is warranted in cases where cord compression is due to extension from the body. Ewing's sarcoma often tends to invade the spinal canal from the paravertebral soft tissue component through the intervertebral foramen, compressing the cord circumferentially. This makes laminectomy an effective approach for cord decompression.[9] In either of the cases, postoperative chemotherapy for control of micrometastases and local control by radiotherapy is warranted. Is cases where the diagnosis is being anticipated prior to neurological compromise, it is advisable to confirm it by needle biopsy, and once made, the patient should be subjected to a three- or four-drug neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen.[10] This would not only help shrink the primary tumor, thereby increasing chances of total excision, but also take care of micrometastasis and give an idea about responsiveness of the tumor to adjuvant therapy.[9] This is followed by surgery or radiotherapy or both. Primary radiotherapy is not advocated in these cases because the posttreatment edema will lead to development or progression of neural compression.

In our patient, the initial presentation of mild low back pain was misinterpreted as due to benign spinal pathology and managed medically. But the onset of rapid lower limb weakness pointed toward a more aggressive pathology. Acute paraplegia as a presenting symptom is extremely rare in Ewing's sarcoma of the nonsacral spine and requires a high index of suspicion in children for early diagnosis. A detailed patient history and a careful physical examination are essential to minimize the delay in diagnosis. An atypical clinical course in a musculoskeletal or neurological condition should alert us to a possible underlying malignant disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bacci G, Picci P, Gherlinzoni F, Capanna R, Calderoni P, Putti C, et al. Localized Ewing's sarcoma of bone: Ten years’ experience at the Instituto Ortopedico Rizzoli in 124 cases treated with multimodal therapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1985;21:163–73. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(85)90168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebb DH, Green DM, Shamberger RC, Tarbell NJ. Solid tumours of childhood. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2005. pp. 1919–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilepich MV, Vietti TJ, Nesbit ME, Tefft M, Kissane J, Burgert O, et al. Ewing's sarcoma of the vertebral column. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1981;7:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(81)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bemporad JA, Sze G, Chaloupka JC, Duncan C. Pseudohemangioma of the vertebra: An unusual radiographic manifestation of primary Ewing's sarcoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:1809–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grubb MR, Currier BL, Pritchard DJ, Ebersold MJ. Primary Ewing's sarcoma of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:309–13. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes DN, Magill HL, Thompson EI, Hayes FA. Primary Ewing's sarcoma: Follow-up with Ga-67 scintigraphy. Radiology. 1990;177:449–53. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.2.2217783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Widhe B, Widhe T. Initial symptoms and clinical features in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:667–74. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharafuddin MJ, Haddad FS, Hitchon PW, Haddad SF, el-Khoury GY. Treatment options in primary Ewing's sarcoma of the spine: Report of seven cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:610–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dini LI, Mendonça R, Gallo P. Primary Ewings sarcoma of the spine: Case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64:654–9. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2006000400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruckner JD, Conrad EU., 3rd . Spine. In: Simon MA, Springfield D, editors. Surgery for bone and soft-tissue tumours. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 435–50. [Google Scholar]