Abstract

Mosquitoes act as a vector for most of the life threatening diseases like malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, chikungunya ferver, filariasis, encephalitis, West Nile Virus infection, etc. Under the Integrated Mosquito Management (IMM), emphasis was given on the application of alternative strategies in mosquito control. The continuous application of synthetic insecticides causes development of resistance in vector species, biological magnification of toxic substances through the food chain and adverse effects on environmental quality and non target organisms including human health. Application of active toxic agents from plant extracts as an alternative mosquito control strategy was available from ancient times. These are non-toxic, easily available at affordable prices, biodegradable and show broad-spectrum target-specific activities against different species of vector mosquitoes. In this article, the current state of knowledge on phytochemical sources and mosquitocidal activity, their mechanism of action on target population, variation of their larvicidal activity according to mosquito species, instar specificity, polarity of solvents used during extraction, nature of active ingredient and promising advances made in biological control of mosquitoes by plant derived secondary metabolites have been reviewed.

Keywords: Insecticides, integrated mosquito management, larvicides, LC50, plant extracts

Introduction

Mosquitoes can transmit more diseases than any other group of arthropods and affect million of people throughout the world. WHO has declared the mosquitoes as “public enemy number one”1. Mosquito borne diseases are prevalent in more than 100 countries across the world, infecting over 700,000,000 people every year globally and 40,000,000 of the Indian population. They act as a vector for most of the life threatening diseases like malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, chikungunya ferver, filariasis, encephalitis, West Nile virus infection, etc., in almost all tropical and subtropical countries and many other parts of the world.

To prevent proliferation of mosquito borne diseases and to improve quality of environment and public health, mosquito control is essential. The major tool in mosquito control operation is the application of synthetic insecticides such as organochlorine and organophosphate compounds. But this has not been very successful due to human, technical, operational, ecological, and economic factors. In recent years, use of many of the former synthetic insecticides in mosquito control programme has been limited. It is due to lack of novel insecticides, high cost of synthetic insecticides, concern for environmental sustainability, harmful effect on human health, and other non-target populations, their non biodegradable nature, higher rate of biological magnification through ecosystem, and increasing insecticide resistance on a global scale2,3. Thus, the Environmental Protection Act in 1969 has framed a number of rules and regulations to check the application of chemical control agents in nature4. It has prompted researchers to look for alternative approaches ranging from provision of or promoting the adoption of effective and transparent mosquito management strategies that focus on public education, monitoring and surveillance, source reduction and environment friendly least-toxic larval control. These factors have resulted in an urge to look for environment friendly, cost-effective, biodegradable and target specific insecticides against mosquito species. Considering these, the application of eco-friedly alternatives such as biological control of vectors has become the central focus of the control programmme in lieu of the chemical insecticides.

One of the most effective alternative approaches under the biological control programme is to explore the floral biodiversity and enter the field of using safer insecticides of botanical origin as a simple and sustainable method of mosquito control. Further, unlike conventional insecticides which are based on a single active ingredient, plant derived insecticides comprise botanical blends of chemical compounds which act concertedly on both behavourial and physiological processes. Thus there is very little chance of pests developing resistance to such substances. Identifying bio-insecticides that are efficient, as well as being suitable and adaptive to ecological conditions, is imperative for continued effective vector control management. Botanicals have widespread insecticidal properties and will obviously work as a new weapon in the arsenal of synthetic insecticides and in future may act as suitable alternative product to fight against mosquito borne diseases.

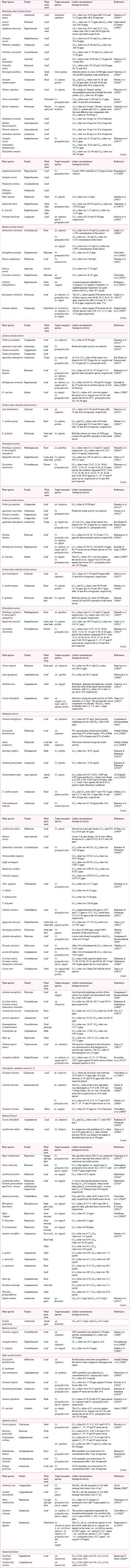

Roark5 described approximately 1,200 plant species having potential insecticidal value, while Sukumar et al6 listed and discussed 344 plant species that only exhibited mosquitocidal activity. Shallan et al in 20057 reviewed the current state of knowledge on larvicidal plant species, extraction processes, growth and reproduction inhibiting phytochemicals, botanical ovicides, synergistic, additive and antagonistic joint action effects of mixtures, residual capacity, effects on non-target organisms, resistance and screening methodologies, and discussed some promising advances made in phytochemical research. Table I summarized the mosquitocidal activities of various herbal products from edible crops, ornamental plants, trees, shrubs, herbs, grasses and marine plants according to the exaction procedure developed in eleven different solvent systems and the nature of mosquitocidal activities against different life stages of different vector species as a ready reference for further studies.

Table I (A).

Efficacy of botanical extracts in controlling/reducing the population of vector mosquitoes

Phytochemicals

Phytochemicals are botanicals which are naturally occurring insecticides obtained from floral resources. Applications of phytochemicals in mosquito control were in use since the 1920s8, but the discovery of synthetic insecticides such as DDT in 1939 side tracked the application of phytochemicals in mosquito control programme. After facing several problems due to injudicious and over application of synthetic insecticides in nature, re-focus on phytochemicals that are easily biodegradable and have no ill-effects on non-target organisms was appreciated. Since then, the search for new bioactive compounds from the plant kingdom and an effort to determine its structure and commercial production has been initiated. At present phytochemicals make upto 1 per cent of world's pesticide market9.

Botanicals are basically secondary metabolites that serve as a means of defence mechanism of the plants to withstand the continuous selection pressure from herbivore predators and other environmental factors. Several groups of phytochemicals such as alkaloids, steroids, terpenoids, essential oils and phenolics from different plants have been reported previously for their insecticidal activities7. Insecticidal effects of plant extracts vary not only according to plant species, mosquito species, geographical varities and parts used, but also due to extraction methodology adopted and the polarity of the solvents used during extraction. A wide selection of plants from herbs, shrubs and large trees was used for extraction of mosquito toxins. Phytochemicals were extracted either from the whole body of little herbs or from various parts like fruits, leaves, stems, barks, roots, etc., of larger plants or trees. In all cases where the most toxic substances were concentrated upon, found and extracted for mosquito control.

Plants produce numerous chemicals, many of which have medicinal and pesticidal properties. More than 2000 plant species have been known to produce chemical factors and metabolites of value in pest control programmes. Members of the plant families- Solanaceae, Asteraceae, Cladophoraceae, Labiatae, Miliaceae, Oocystaceae and Rutaceae have various types of larval, adulticidal or repellent activities against different species of mosquitoes7.

Application of phytochemicals as mosquito larvicide: An essential component of IMM

Human beings have used plant parts, products and secondary metabolites of plant origin in pest control since early historical times. Vector control has been practiced since the early 20th century. During the pre-DDT era, reduction of vector mosquitoes mainly depended on environmental management of breeding habitats, i.e., source reduction. During that period, some botanical insecticides used in different countries were Chrysanthemum, Pyrethrum, Derris, Quassia, Nicotine, Hellebore, Anabasine, Azadirachtin, d-limonene camphor, Turpentine, etc7.

From the early 1950s, DDT and other synthetic organochloride and organophosphate insecticides were extensively used to interrupt transmission of vector borne diseases by reducing densities, human-vector contact and, in particular, the longevity of vector mosquitoes. In the mid-1970s, the resurgence of vector borne diseases, along with development of insecticide resistance in vector population, poor human acceptance of indoor house spraying and environmental concerns against the use of insecticides led to a rethinking in vector control strategies10. As a result, emphasis was given on the application of alternative methods in mosquito control as part of the Integrated Mosquito Management (IMM)11. Integrated Mosquito Management (IMM) is a decision-making process for the management of mosquito populations, involving a combination of methods and strategies for long-term maintenance of low levels of vectors. The purpose of IMM is to protect public health from diseases transmitted by mosquitoes, maintain healthy environment through proper use and disposal of pesticides and improve the overall quality of life through practical and effective pest control strategies. The main approaches of IMM include: (i) Source reduction and habitat management by proper sanitation, water management in temporary and permanent water bodies, and channel irrigation. Vegetation management is also necessary to eliminate protection and food for mosquito larvae; (ii) Larviciding by application of dipteran specific bacteria, insect growth regulators, surface films and oils, expanded polystyrene beads, phytochemicals, organophosphates and organochlorides, (iii) Adulticiding by application of synthetic pyrethroids, organophosphates and synthetic or plant derived repellents, insecticide impregnated bed nets, genetic manipulations of vector species, etc., (iv) Use of mosquito density assessment in adult and larval condition and disease surveillance; and (v) Application of biological control methods by using entomophagous bacteria, fungi, microsporidians, predators and parasites.

Of the above avenues of IMM, larviciding approach is the more proactive, proenvironment, target specific and safer approach than controlling adult mosquitoes. Application of larvicide from botanical origin was extensively studied as an essential part of IMM, and various mosquito control agents such as ocimenone, rotenone, capllin, quassin, thymol, eugenol, neolignans, arborine and goniothalamin were developed7.

Variation of larvicidal potentiality according to mosquito species, plant parts and polarity of solvents used

The efficacy of phytochemicals against mosquito larvae can vary significantly depending on plant species, plant parts used, age of plant parts (young, mature or senescent), solvent used during extraction as well as upon the available vector species. Sukumar et al6 have described the existence of variations in the level of effectiveness of phytochemical compounds on target mosquito species vis-à-vis plant parts from which these were extracted, responses in species and their developmental stages against the specified extract, solvent of extraction, geographical origin of the plant, photosensitivity of some of the compounds in the extract, effect on growth and reproduction. Changes in the larvicidal efficacy of the plant extracts occurred due to geographical origin of the plant (in Citrus sp18,39,64,65, Jatropha sp13,20,21, Ocimum sanctum22,35,65,82, Momordica charantia22,24,49, Piper sp54,63,89,95 and Azadirechta indica65); response in the different mosquito species (in Curcuma domestica26, Withania somnifera13, Jatropha curcas13,20, Piper retrofractum63, Cestrum diurnum58, Citrullus vulgaris50,71, and Tridax procumbens30,31 ); due to variation in the species of plant examined (in Euphorbia sp22,28,37,51, Phyllanthus sp20, Curcuma sp36, Solanum sp16,29,57,60,75,79,96, Ocimum sp23,35,65,82, Eucalyptus sp22,28,37,51, Plumbago sp20, Vitex sp50,93, Piper sp54,63,89,95, Annona sp48,54,69, and Cleome sp31,78) and between plant parts used to study the larvicidal efficacy (in Euphorbia tirucalli28,51, Solanum xanthocarpum16, Azadirechta indica65, Solanum villosum57,60,79,96, Annona squamosa48,54,69, Withania somnifera13, Melia azedarach45, Moringa oleifera46 and Ocimum sanctum35,82). However, the principal objective of the present documentation is to report the changes in larvicidal potentiality of the plant extracts due to change of the particular solvent used during extraction. Variation of the larvicidal potential of the same plant changed with the solvents used as evidenced in case of Solanum xanthocarpum16, Euphorbia tirucalli28,51, Momordica charantia22,24,49, Eucalyptus globules14,15,28,83, Citrullus colocynthis13, Azadirechta indica65, Annona squamosa48,54,69 and Solanum nigrum29,75.

It has been shown that the extraction of active biochemical from plants depends upon the polarity of the solvents used. Polar solvent will extract polar molecules and non-polar solvents extract non-polar molecules. This was achieved by using mainly eleven solvent systems ranging from hexane/ petroleum ether, the most non polar (polarity index of 0.1 that mainly extracts essential oil) to that of water, the most polar (polarity index of 10.2) that extracts biochemical with higher molecular weights such as proteins, glycans, etc. Chloroform or ethyl acetate are moderately polar (polarity index of 4.1) that mainly extracts steroids, alkaloids, etc. It has been found that in most of the studies solvent with minimum polarity have been used such as hexane or petroleum ether or that with maximum polarity such as aqueous/ steam distillation. However, those biochemical that were extracted using moderately polar solvents were also seen to give good results as reported by a few bioassay. Thus, different solvent types can significantly affect the potency of extracted plant compounds and there is difference in the chemo-profile of the plant species. In Table I, the lowest LC50 value was reported in Solenostemma argel against Cx. pipiens47. Several other plants such as Nyctanthes arbotristis38, Atlantia monophylla57, Centella asiatica40, Cryptotaenia paniculata76 were also reported with promising LC50 values. These extracts may be fractioned in order to locate the particular bioactive toxic agent responsible for larval toxicity. Table I also reported that most of the studies were carried out on Culex mosquitoes and Aedes was the least frequently chosen mosquitoes for all the experiments. In several studies, instead of a particular solvent, combination of solvents or serial extraction by different solvents according to their polarity has also been tried and good larvicidal potentiality found as a result96.

Nature of active ingredients responsible for larval toxicity

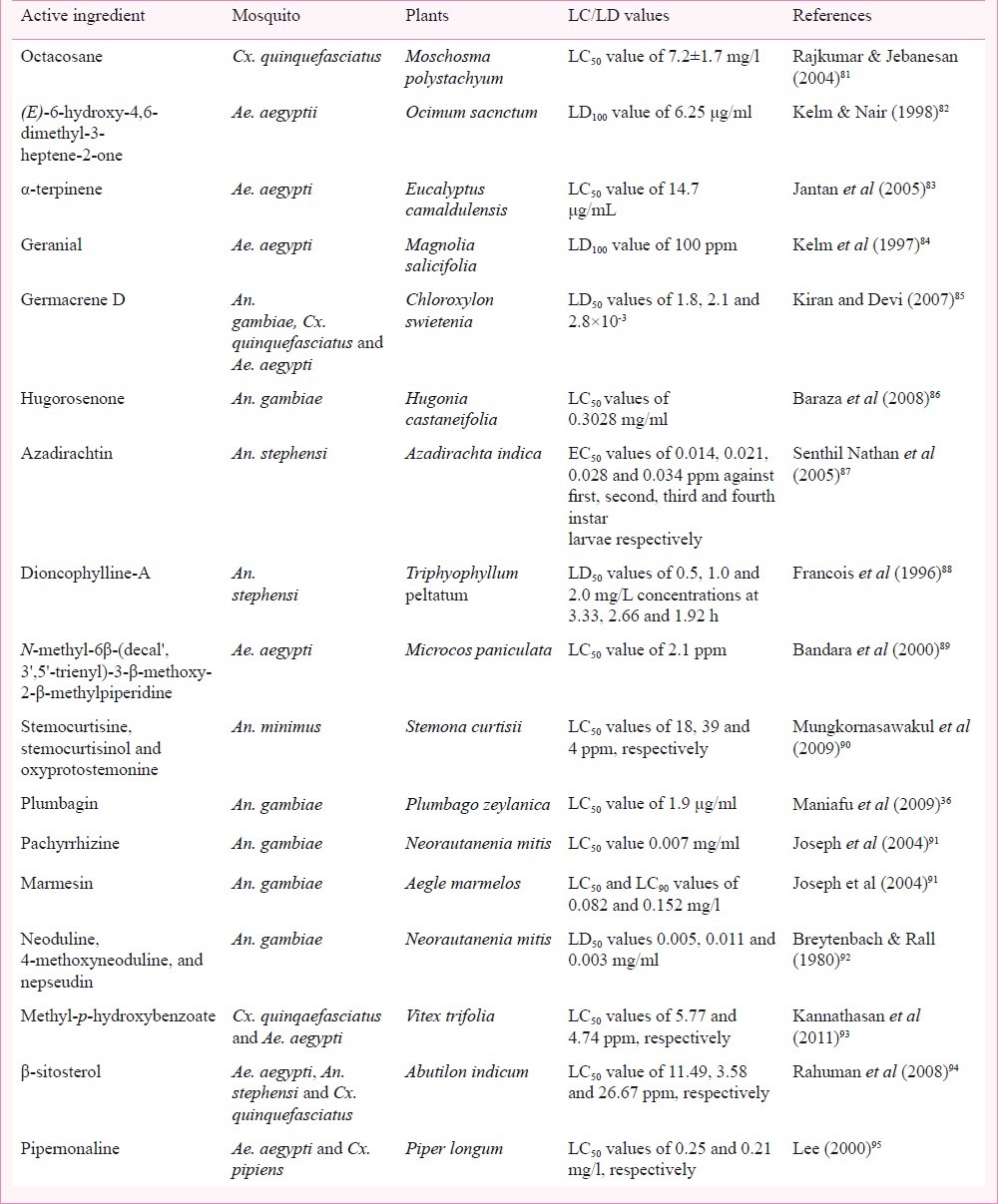

The plant world comprises a rich untapped pool of phytochemicals that may be widely used in place of synthetic insecticides in mosquito control programme. Kishore et al97 reviewed the efficacy of phytochemicals against mosquito larvae according to their chemical nature and described the mosquito larvicidal potentiality of several plant derived secondary materials, such as, alkanes, alkenes, alkynes and simple aromatics, lactones, essential oils and fatty acids, terpenes, alkaloids, steroids, isoflavonoids, pterocarpans and lignans. They also documented the isolation of several bioactive toxic principles from various plants and reported their toxicity against different mosquito species (Table II).

Table II.

Identification of various bioactive toxic principles from plant extract and their relative mosquitocidal efficacy

Mode of action of phytochemicals in target insect body

Generally the active toxic ingredients of plant extracts are secondary metabolites that are evolved to protect them from herbivores. The insects feed on these secondary metabolites potentially encountering toxic substances with relatively non-specific effects on a wide range of molecular targets. These targets range from proteins (enzymes, receptors, signaling molecules, ion-channels and structural proteins), nucleic acids, biomembranes, and other cellular components98. This in turn, affects insect physiology in many different ways and at various receptor sites, the principal of which is abnormality in the nervous system (such as, in neurotransmitter synthesis, storage, release, binding, and re-uptake, receptor activation and function, enzymes involved in signal transduction pathway)98. Rattan98 reviewed the mechanism of action of plant secondary metabolites on insect body and documented several physiological disruptions, such as inhibition of acetylecholinestrase (by essential oils), GABA-gated chloride channel (by thymol), sodium and potassium ion exchange disruption (by pyrethrin) and inhibition of cellular respiration (by rotenone). Such disruption also includes the blockage of calcium channels (by ryanodine), of nerve cell membrane action (by sabadilla), of octopamine receptors (thymol), hormonal balance disruption, mitotic poisioning (by azadirachtin), disruption of the molecular events of morphogenesis and alteration in the behaviour and memory of cholinergic system (by essential oil), etc. Of these, the most important activity is the inhibition of acetylcholinerase activity (AChE) as it is a key enzyme responsible for terminating the nerve impulse transmission through synaptic pathway; AChE has been observed to be organophosphorus and carbamate resistant, and it is well-known that the alteration in AChE is one of the main resistance mechanisms in insect pests99.

Scope for future research: isolation of toxic larvicidal active ingredients

Several studies have documented the efficacy of plant extracts as the reservoier pool of bioactive toxic agents against mosquito larvae. But only a few have been commercially produced and extensively used in vector control programmes. The main reasons behind the failure in laboratory to land movements of bioactive toxic phytochemicals are poor characterization and inefficiency in determining the structure of active toxic ingredients responsible for larvicidal activity. For the production of a green biopesticide, the following steps can be recommended during any research design with phytochemicals: (i) Screening of floral biodiversity in search of crude plant extracts having mosquito larvicidal potentiality; (ii) Preparation of plant solvent extracts starting from non-polar to polar chemicals and determination of the most effective solvent extract; (iii) Evaporation of the liquid solvent to obtain solid residue and determination of the lethal concentration (LC50/LC100 values); (iv) Phytochemical analysis of the solid residue and application of column chromatography and thin layer chromatography to purify and isolate toxic phytochemical with larvicidal potentiality; (v) Determination of the structure of active principle by infra red (IR) spectroscopic, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy (GCMS) analysis; (vi) Study of the effect of active ingredient on non target organisms; and (vii) Field evaluation of the active principle before its recommendation in vector control programme and commercial production.

Conclusion

Today, environmental safety is considered to be of paramount importance. An insecticide does not need to cause high mortality on target organisms in order to be acceptable but should be eco-friedly in nature. Phytochemicals may serve as these are relatively safe, inexpensive and readily available in many parts of the world. Several plants are used in traditional medicines for the mosquito larvicidal activities in many parts of the world. According to Bowers et al100, the screening of locally available medicinal plants for mosquito control would generate local employment, reduce dependence on expensive and imported products, and stimulate local efforts to enhance the public health system. The ethno-pharmacological approaches used in the search of new bioactive toxins from plants appear to be predictive compared to the random screening approach. The recently developed new isolation techniques and chemical characterization through different types of spectroscopy and chromatography together with new pharmacological testing have led to an interest in plants as the source of new larvicidal compounds. Synergestic approaches such as application of mosquito predators with botanical blends and microbial pesticides will provide a better effect in reducing the vector population and the magnitude of epidemiology.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Shri Anindya Sen (Department of English, Bankura Christian College) for critically examine the manuscript. The financial support provided by University Grants Commission to Dr Anupam Ghosh is also acknowledged.

References

- 1.Report of the WHO informal consultation on the evaluation on the testing of insecticides, CTD/WHO PES/IC/96.1. Geneva: WHO; 1996. World Health Organization; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown AW. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: a pragmatic review. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1986;2:123–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell TL, Kay BH, Skilleter GA. Environmental effects of mosquito insecticides on saltmarsh invertebrate fauna. Aquat Biol. 2009;6:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt RP, Khanal SN. Environmental impact assessment system in Nepal - an overview of policy, legal instruments and process. Kathmandu Univ J Sci Enginnering Tech. 2009;5:160–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roark RC. Some promising insecticidal plants. Econ Bot. 1947;1:437–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sukumar K, Perich MJ, Boobar LR. Botanical derivatives in mosquito control: a review. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1991;7:210–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaalan EAS, Canyonb D, Younesc MWF, Abdel-Wahaba H, Mansoura AH. A review of botanical phytochemicals with mosquitocidal potential. Environ Int. 2005;3:1149–66. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahi M, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Iranshahi M, Vatandoost H, Hanafi-Bojd MY. Larvicidal efficacy of latex and extract of Calotropis procera (Gentianales: Asclepiadaceae) against Culex quinquefasciatus and Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) J Vector Borne Dis. 2010;47:185–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isman MB. Neem and other Botanical insecticides: Barriers to commercialization. Phytoparasitica. 1997;25:339–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Regional Framework for an Integrated Vector Management Strategy for the South-East Asia Region. 2005:1–13. SEA-VBC-86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose RI. Pesticides and public health: integrated methods of mosquito management. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:17–23. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P, Mohan L, Srivastava CN. Phytoextract-induced developmental deformities in malaria vector. Bioresource Tech. 2006;97:1599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakthivadivel M, Daniel T. Evaluation of certain insecticidal plants for the control of vector mosquitoes viz. Culex quinquefasciatus, Anopheles stephensi and Aedes aegypti. Appl Entomol Zool. 2008;43:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maurya P, Mohan L, Sharma P, Batabyal L, Srivastava CN. Larvicidal efficacy of Aloe barbadensis and Cannabis sativa against the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi (Diptera: Culicidae) Entomol Res. 2007;37:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheeren ME. Larvicidal effects of Eucalyptus extracts on the larvae of Culex pipiens mosquito. Int J Agric Biol. 2006;8:896–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohan L, Sharma P, Shrivastava CN. Evaluation of Solanum xanthocarpum extract as a synergist for cypermethrin against larvae of filarial vector Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) Entomol Res. 2006;36:220–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansour SA, Messeha SS, EL-Gengaihi SE. Botanical biocides. Mosquitocidal activity of certain Thymus capitatus constituents. J Nat Tox. 2000;9:49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassir JT, Mohsen ZH, Mehdi NS. Toxic effects of limonene against Culex quinquefasciatus Say larvae and its interference with oviposition. J Pest Sci. 1989;62:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traboulsi AF, Taoubi K, El-Haj S, Bessiere JM, Salma R. Insecticidal properties of essential plant oils against the mosquito Culex pipiens molestus (Diptera: Culicidae) Pest Management Sci. 2002;58:491–5. doi: 10.1002/ps.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahuman AA, Gopalakrishnan G, Venkatesan P, Geetha K. Larvicidal activity of some Euphorbiaceae plant extracts aginst Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol Res. 2007;102:867–73. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0839-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karmegan N, Sakthivadivel M, Anuradha V, Daniel T. Indigenous plant extracts as larvicidal agents against Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Bioresource Technol. 1997;5:137–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahuman AA, Venkatesan P. Larvicidal efficacy of five cucurbitaceous plant leaf extracts against mosquito species. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:133–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurya P, Sharma P, Mohan L, Batabyal L, Srivastava CN. Evaluation of the toxicity of different phytoextracts of Ocimum basilicum against Anopheles stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus. J Asia-Pacific Entomol. 2009;12:113–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh RK, Dhiman RC, Mittal PK. Mosquito larvicidal properties of Momordica charantia Linn (Family: Cucurbitaceae) J Vect Borne Dis. 2006;43:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choochate W, Kanjanapothi D, Panthong A, Taesotikul T, Jitpakdi A, Chaithong U, et al. Larvicidal, adulticital and repellent effects of Kaempferia galangal. South East J Trop Med Publ Hlth. 1999;30:470–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choochate W, Chaiyasit D, Kanjanapothi D, Rattanachanpichai E, Jitpakdi A, Tuetun B, et al. Chemical composition and anti-mosquito potential of rhizome extract and volatile oil derived from Curcuma aromatica against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) J Vector Ecol. 2005;30:302–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodrigues AMS, Paula JE, Roblot F, Fournet A, Espíndola LS. Larvicidal activity of Cybistax antisyphilitica against Aedes aegypti larvae. Fitoterapia. 2005;76:755–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh RK, Dhiman RC, Mittal PK. Studies on mosquito larvicidal properties of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook (family-Myrtaceae) J Comm Dis. 2007;39:233–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghavendra K, Singh SP, Subbarao SK, Dash AP. Laboratory studies on mosquito larvicidal efficacy of aqueous & hexane extracts of dried fruit of Solanum nigrum Linn. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:74–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamaraj C, Bagavan A, Elango G, Zahir AA, Rajkumar G, Mariamuthu S, et al. Larvicidal activity of medicinal plant extracts against Anopheles stephensi and Culex tritaeniorhynchus. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:101–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saxena RC, Dixit OP, Sukumaran P. Laboratory assessment of indigenous plant extracts for anti-juvenile hormone activity in Culex quinquefasciatus. Indian J Med Res. 1992;95:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raj Mohan D, Ramaswamy M. Evaluation of larvicidal activity of the leaf extract of a weed plant, Ageratina adenophora, against two important species of mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus. Afr J Biotech. 2007;6:631–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahumana AA, Gopalakrishnan G, Ghouse S, Arumugam S, Himalayan B. Effect of Feronia limonia on mosquito Larvae. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:553–5. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaushik R, Saini P. Larvicidal activity of leaf extract of Millingtonia hortensis (Family: Bignoniaceae) against Anopheles stephensi, Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes aegypti. J Vector Borne Dis. 2008;45:66–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anees AM. Larvicidal activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn. (Labiatae) against Aedes aegypti (L.) and Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) Parasitol Res. 2008;101:1451–3. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maniafu BM, Wilber L, Ndiege IO, Wanjala CCT, Akenga TA. Larvicidal activity of extracts from three Plumbago spp against Anopheles gambiae. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:813–7. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yadav R, Srivastava VK, Chandra R, Singh A. Larvicidal activity of Latex and stem bark of Euphorbia tirucalli plant on the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus. J Communicable Dis. 2002;34:264–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khatune NA, Md. Haque E, Md. Mosaddik A. Laboratory Evaluation of Nyctanthes arbortristis Linn. flower extract and its isolated compound against common filarial Vector, Cufex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: culicidae) Larvae. Pak J Bio Sci. 2001;4:585–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagavan A, Kamaraj C, Rahuman A, Elango G, Zahir AA, Pandiyan G. Evaluation of larvicidal and nymphicidal potential of plant extracts against Anopheles subpictus Grassi, Culex tritaeniorhynchus Giles and Aphis gossypii Glover. Parasitol Res. 2009;104:1109–17. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matasyoh JC, Wathuta EM, Kairuki ST, Chepkorir R, Kavulani J. Aloe plant extracts as alternative larvicides for mosquito control. Afr J Biotech. 2008;7:912–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yenesew A, Derese S, Midiwo JO, Heydenreich M, Peter MJ. Effect of rotenoids from the seeds of Millettia dura on larvae of Aedes aegypti. Pest Manage Sci. 2003;59:1159–61. doi: 10.1002/ps.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang YC, Lim MY, Lee HS. Emodin isolated from Cassia obtusifolia (Leguminosae) seed shows larvicidal activity against three mosquito specie. J Agri Food Chem. 2003;51:7629–31. doi: 10.1021/jf034727t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sivagnaname S, Kalyanasundaram M. Laboratory evaluation of Methanolic extract of Atlanta monophylla (Family: Rutaceae) against immature stage of mosquitoes and non-target organisms. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:115–8. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senthil-Nathan S, Kalaivani K, Sehoon K. Effects of Dysoxylum malabaricum Bedd. (Meliaceae) extract on the malarial vector Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae) Bioresource Tech. 2006;97:2077–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senthil Nathan S, Savitha G, George DK, Narmadha A, Suganya L, Chung PG. Efficacy of Melia azedarach L. extract on the malarial vector Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae) Bioresource Tech. 2006;97:1316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamaraj C, Rahuman AA. Larvicidal and adulticidal potential of medicinal plant extracts from south India against vectors. Asian Pacific J Trop Med. 2010;3:948–53. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Doghairi M, El-Nadi A, El hag E, Al-Ayedh H. Effect of Solenostemma argel on oviposition, egg hatchability and viability of Culex pipiens L. larvae. Phytother Res. 2004;18:335–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamaraj C, Rahuman AA, Bagavan A, Abduz Zahir A, Elango G, Kandan P, et al. Larvicidal efficacy of medicinal plant extracts against Anopheles stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) Trop Biomed. 2010;27:211–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prabhakar K, Jebanesa A. Larvicidal efficacy of some cucurbitacious plant leaf extracts against Culex quinquefasciatus. Bioresource Tech. 2004;95:113–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishnan K, Senthilkumar A, Chandrasekaran M, Venkatesalu V. Differential larvicidal efficacy of four species of Vitex against Culex quinquefasciatus larvae. Parasitol Res. 2007;10:1721–3. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0714-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajkumar S, Jebanesan A. Larvicidal and adult emergence inhibition effect of Centella asiatica Brahmi (umbelliferae) against mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) Afr J Biomed Res. 2005;8:31–3. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vahitha R, Venkatachalam MR, Murugan K, Jebanesan A. Larvicidal efficacy of Pavonia zeylanica L. and Acacia ferruginea D.C. against Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Bioresource Tech. 2002;82:203–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(01)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jang YS, Baek BR, Yang YC, Kim MK, Lee HS. Larvicidal activity of leguminous seeds and grains against Aedes aegypti and Culex pipiens pallens. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2002;18:210–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Das NG, Goswami D, Rabha B. Preliminary evaluation of mosquito larvicidal efficacy of plant extracts. J Vect Borne Dis. 2007;44:145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jang YS, Jeon JH, Lee HS. Mosquito larvicidal activity of active constituent derived from Chamaecyparis obtusa leaves against 3 mosquito species. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2005;21:400–3. doi: 10.2987/8756-971X(2006)21[400:MLAOAC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kovendan K, Murugan K, Vincent S. Evaluation of larvicidal activity of Acalypha alnifolia Klein ex Willd.(Euphorbiaceae) leaf extract against the malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi, dengue vector, Aedes aegypti and Bancroftian filariasis vector, Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol Res. 2012;110:571–81. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2525-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chowdhury N, Chatterjee SK, Laskar S, Chandra G. Larvicidal activity of Solanum villosum Mill (Solanaceae: Solanales) leaves to Anopheles subpictus Grassi (Diptera: Culicidae) with effect on non-target Chironomus circumdatus Kieffer (Diptera: Chironomidae) J Pest Sci. 2009;82:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ghosh A, Chandra G. Biocontrol efficacy of Cestrum diurnum (L.) (Solanales: Solanaceae) against the larval forms of Anopheles stephensi. Nat Prod Res. 2006;20:371–9. doi: 10.1080/14786410600661575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghosh A, Chowdhury N, Chandra G. Laboratory evaluation of a phytosteroid compound of mature leaves of Day Jasmine (Solanaceae: Solanales) against larvae of Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) and nontarget organisms. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:271–7. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0963-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chowdhury N, Ghosh A, Chandra G. Mosquito larvicidal activities of Solanum villosum berry extract against the Dengue vector Stegomyia aegypti. BMC Comple Alternative Med. 2008;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajkumar S, Jebanesan A. Larvicidal and oviposition activity of Cassia obtusifolia Linn (Family: Leguminosae) leaf extract against malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol Res. 2009;104:337–40. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Azmi MA, Naqvi SNH, Ahmad I, Tabassum R, Anbreen B. Toxicity of neem leaves extract (NLX) compared with malathion (57 E.C.) against late 3rd instar larvae of Culex fatigans (Wild Strain) by WHO method. Turk J Zool. 1998;22:213–8. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chansang U, Zahiri NS, Bansiddhi J, Boonruad T, Thongsrirak P, Mingmuang J, et al. Mosquito larvicidal activity of crude extracts of long pepper (Piper retrofractum vahl) from Thailland. J Vector Ecol. 2005;30:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sumroiphon S, Yuwaree C, Arunlertaree C, Komalamisra N, Rongsriyam Y. Bioactivity of citrus seed for mosquito-borne diseases larval control. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Pub Hlth. 2006;37(Suppl 3):123–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mgbemena IC. Comparative evaluation of larvicidal potentials of three plant extracts on Aedes aegypti. J Am Sci. 2010;6:435–40. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choochate W, Tuetun B, Kanjanapothi D, Rattanachanpichai E, Chaithong U, Chaiwong P, et al. Potential of crude seed extract of celery, Apium graveolens L., against the mosquito Aedes aegypti (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae) J Vector Ecol. 2004;29:340–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kabaru JM, Gichia L. Insecticidal activity of extracts derived from different parts of the mangrove tree Rhizophora mucronata (Rhizophoraceae) Lam. against three arthropods. Afr J Sci Tech. 2001;2:44–9. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chaithong U, Choochote W, Kamsuk K, Jitpakdi A, Tippawangkosol P, Chaiyasit D, et al. Larvicidal effect of pepper plants on Aedes aegypti (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae) J Vector Ecol. 2006;31:138–44. doi: 10.3376/1081-1710(2006)31[138:leoppo]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Omena de C, Navarro DMAF, Paula de JE, Ferreira de Lima JSMR, Sant’Ana AEG. Larvicidal activities against Aedes aegypti of Brazilian medicinal plants. Bioresource Technol. 2007;98:2549–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Macêdo ME, Consoli RAGB, Grandi TSM, Anjos AMG, Oliveira AB, Mendes NM, et al. Screening of Asteraceae (Compositae) plant extracts for larvicidal activity against Aedes fluviatilis (Diptera: Culicidae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:565–70. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000400024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mullai K, Jebanesan A, Pushpanathan T. Mosquitocidal and repellent activity of the leaf extract of Citrullus vulgaris (cucurbitaceae) against the malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi liston (diptera culicidae) Euro Rev Med Pharma Sci. 2008;12:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Govindarajan M, Jebanesan A, Pushpanathan T, Samidurai K. Studies on effect of Acalypha indica L. (Euphorbiaceae) leaf extracts on the malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasil Res. 2008;103:691–5. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mullai K, Jebanesan A. Larvicidal, ovicidal and repellent activities of the leaf extract of two cucurbitacious plants against filarial vector Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) (Diptera: Culicidae) Trop Biomed. 2007;24:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Senthil Nathan S, Hisham A, Jayakumar G. Larvicidal and growth inhibition of the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi by triterpenes from Dysoxylum malabaricum and Dysoxylum beddomei. Fitoterapia. 2008;79:106–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rawani A, Ghosh A, Chandra G. Mosquito larvicidal activities of Solanum nigrum L. leaf extract against Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:1235–40. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rawani A, Mallick Haldar K, Ghosh A, Chandra G. Larvicidal activities of three plants against filarial vector Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera: Culicidae) Parasitol Res. 2009;105:1411–7. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1573-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khanna G, Kannabiran K. Larvicidal effect of Hemidesmus indicus, Gymnema sylvestre, and Eclipta prostrata against Culex qinquifaciatus mosquito larvae. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:307–11. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aly MZY, Badran RAM. Mosquito control with extracts from plants of the Egyptian Eastern Desert. J Herbs Spices Medicinl Plants. 1996;3:3540–80. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chowdhury N, Laskar S, Chandra G. Mosquito larvicidal and antimicrobial activity of protein of Solanum villosum leaves. BMC Comple Alter Med. 2008;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iannacone J, Pérez D. Insecticidal effect of Paullinia clavigera var.bullata Simpson (Sapindaceae) and Tradescantia zebrina Hort ex Bosse (Commelinaceae) in the control of Anopheles benarrochi Gabaldon, Cova García & López 1941, main vector of malaria in Ucayali, Peru. Ecol Aplicada. 2004;3:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rajkumar S, Jebanesan A. Mosquitocidal activities of octacosane from Moschosma polystachyum Linn (lamiaceae) J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:87–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kelm MA, Nair MG. Mosquitocidal compounds and a triglyceride, 1, 3 dilinoleneoyl-2-palmitin, from Ocimum sanctum. J Agri Food Chem. 1998;46:3092–4. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jantan I, Yalvema MF, Ahmad NW, Jamal JA. Insecticidal activities of the leaf oils of eight Cinnamomum species against Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Pharmceutical Biol. 2005;43:526–32. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kelm MA, Nair MG, Schutzki RA. Mosquitocidal compounds from Magnolia salicifolia. Int J Pharmacog. 1997;35:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kiran SR, Devi PS. Evaluation of mosquitocidal activity of essential oil and sesquiterpenes from leaves of Chloroxylon swietenia DC. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:413–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Baraza LD, Joseph CC, Munissi JJE, Nkunya MHH, Arnold N, Porzel A, et al. Antifungal rosane diterpenes and otherconstituents of Hugonia castaneifolia. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:200–5. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Senthil Nathan S, Kalaivani K, Murugan K. Effects of neem limonoids on the malaria vector, Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae) Acta Trop. 2005;96:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Francois G, Looveren MV, Timperman G, Chimanuka B, Assi LA, Holenz J, et al. Larvicidal activity of the naphthylisoquinoline alkaloid dioncophylline-A against the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;54:125–30. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bandara KANP, Kumar V, Jacobsson U, Molleyres LP. Insecticidal piperidine alkaloid from Microcos paniculata stem bark. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mungkornasawakul P, Chaiyong S, Sastraruji T, Jatisatienr A, Jatisatienr C, Pyne SG, et al. Alkaloids from the roots of Stemona aphylla. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:848–51. doi: 10.1021/np900030y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Joseph CC, Ndoile MM, Malima RC, Nkunya MHH. Larvicidal and mosquitocidal extracts, a coumarin, isoflavonoids and pterocarpans from Neorautanenia mitis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004;98:451–5. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Breytenbach JC, Rall GJH. Structure and synthesis of isoflavonoid analogues from Neorautanenia amboensis Schinz. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1980;1:1804–9. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kannathasan K, Senthilkumar A, Venkatesalu V. Mosquito larvicidal activity of methyl-p-hydroxybenzoate isolated from the leaves of Vitex trifolia Linn. Acta Tropica. 2011;120:115–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rahuman AA, Gopalakrishnan G, Venkatesan P, Geetha K. Isolation and identification of mosquito larvicidal compound from Abutilon indicum (Linn.) Sweet. Parasitol Res. 2008;102:981–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0864-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee SE. Mosquito larvicidal activity of pipernonaline, a piperidine alkaloid derived from long pepper, Piper longum. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2000;16:245–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chowdhury N, Bhattacharjee I, Laskar S, Chandra G. Efficacy of Solanum villosum Mill.(Solanaceae: Solanales) as a biocontrol agent against fourth Instar larvae of Culex quinquefasciatus Say. Turk J Zool. 2007;31:365–70. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kishore N, Mishra BB, Tiwari VK, Tripathi V. A review on natural products with mosquitosidal potentials. In: Tiwari VK, editor. Opportunity, challenge and scope of natural products in medicinal chemistry. Kerala: Research Signpost; 2011. pp. 335–65. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rattan RS. Mechanism of action of insecticidal secondary metabolites of plant origin. Crop Protec. 2010;29:913–20. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Senthilnathan S, Choi MY, Seo HY, Paik CH, Kalaivani K, Kim JD. Effect of azadirachtin on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity and histology of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) Ecotox Environ Safety. 2008;70:244–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bowers WS, Sener B, Evans PH, Bingol F, Erdogan I. Activity of Turkish medicinal plants against mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. Insect Sci Appl. 1995;16:339–42. [Google Scholar]