Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Over the last two decades, numerous studies have indicated the feasibility of minimally invasive surgery for early cervical cancer without compromising the oncological outcome.

OBJECTIVE:

Systematic literature review and meta analysis aimed at evaluating the outcome of laparoscopic and robotic radical hysterectomy (LRH and RRH) and comparing the results with abdominal radical hysterectomy (ARH).

SEARCH STRATEGY:

Medline, PubMed, Embase, Cochrane library and Reference lists were searched for articles published until January 31st 2011, using the terms radical hysterectomy, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, robotic radical hysterectomy, surgical treatment of cervical cancer and complications of radical hysterectomy.

SELECTION CRITERIA:

Studies that reported outcome measures of radical hysterectomy by open method, laparoscopic and robotic methods were selected. Data collection and analysis: Two independent reviewers selected studies, abstracted and tabulated the data and pooled estimates were obtained on the surgical and oncological outcomes.

RESULTS:

Mean sample size, age and body mass index across the three types of RH studies were similar. Mean operation time across the three types of RH studies was comparable. Mean blood loss and transfusion rate are significantly higher in ARH compared to both LRH and RRH. Duration of stay in hospital for RRH was significantly less than the other two methods. The mean number of lymph nodes obtained, nodal metastasis and positive margins across the three types of RH studies were similar. Post operative infectious morbidity was significantly higher among patients who underwent ARH compared to the other two methods and a higher rate of cystotomy in LRH.

CONCLUSIONS:

Minimally invasive surgery especially robotic radical hysterectomy may be a better and safe option for surgical treatment of cervical cancer. The laparoscopic method is not free from complications. However, experience of surgeon may reduce the complications rate.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, hysterectomy, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy

INTRODUCTION

Open radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection has been considered as the standard surgical treatment for early stage cervical cancer for more than 100 years.[1] After the first total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy which was performed by Nezhat et al in June of 1989,[2] in the last two decades minimally invasive endoscopic surgery has become an acceptable alternative for open method. In recent years, robotic surgery became popular and the first robotic radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy performed in 2006 by Sert and Abeler.[3] The benefits of minimal invasive surgery are less wound related problems, increased patients comfort, better visualization, less blood loss, short recovery time, decreased analgesic requirements, shorter hospital stay and early recovery.[4] The use of robotic surgery has been said to be associated with faster performance times, increased accuracy, enhanced dexterity, faster suturing, and reduced number of errors when compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery.[5,6] However, debate exists on two points. These are the oncological outcome and the safety of the procedures. So far, there are no prospective randomised controlled studies available in these aspects. Recently one prospective randomised controlled study on laparoscopic vs abdominal radical hysterectomy in patients with early cervical cancer was conducted by U.S. National Institutes of Health, (clinical trials. govStudy NCT01258413) and has been completed. However, its results are not available. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on outcomes of laparoscopic, robotic and open abdominal methods of radical hysterectomy and compared the data to aggregate the current best evidence on the subject.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources

A systematic literature search was performed independently by the two authors in January 2011 using online databases for medical literature from 1980 onwards [MEDLINE, EMBASE, BioMed Central, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)]. In order to maximize the probability of identifying potentially relevant articles, broad search terms were used (cervical cancers, gynaecological malignancies, minimally invasive surgeries). Additional searches were made by screening reference lists from articles of interest, as well as citations of articles of interest. Furthermore, attempts were made to identify relevant unpublished studies by searching the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ClinicalTrials.gov, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN) and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Study selection and statistical analysis

Articles in any language were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis if they reported one or more oncological and surgical outcome measures for treatment of early cervical cancer and English translation was available. There were 1560 articles identified by search. About 320 articles were potentially relevant. Others were deemed irrelevant based on title and or abstract. There were 21 studies available for laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, 12 for robotic radical hysterectomy and 14 for open radical hysterectomy. Others were excluded due to various reasons. Some full articles, reviews and meta-analyses were non-English. Studies which included advanced stage of cervical cancers, those treated with chemotherapy prior to surgery, original data was not presented, and articles in which outcome of interest was not reported. All studies were observational cohort studies. No RCTs were available.The article was prepared following the guidelines proposed by the Meta analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Statement.[7] We used published data from literature and thus the present study was exempted from Local Research and Ethics Committee approval. Details such as sample size, mean age in years, body mass index, mean operating time, mean blood loss, oncological data like mean lymph node yield, nodal metastasis, recurrence, and intra operative and postoperative complications were collected from studies published on radical hysterectomy. Distributions of these variables in studies using abdominal, laparoscopic and robotic radical hysterectomy are presented in Tables. Mean of these variables across the three types of radical hysterectomy was compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc comparison of means was carried out using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

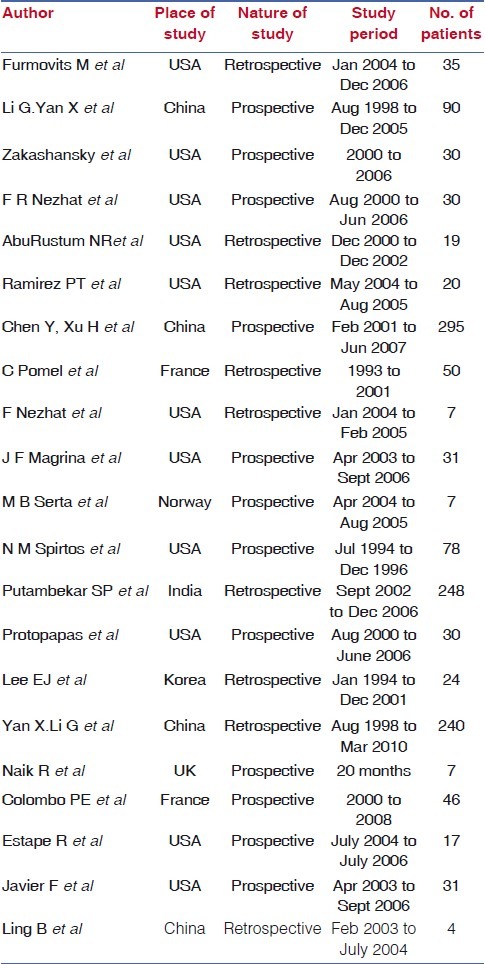

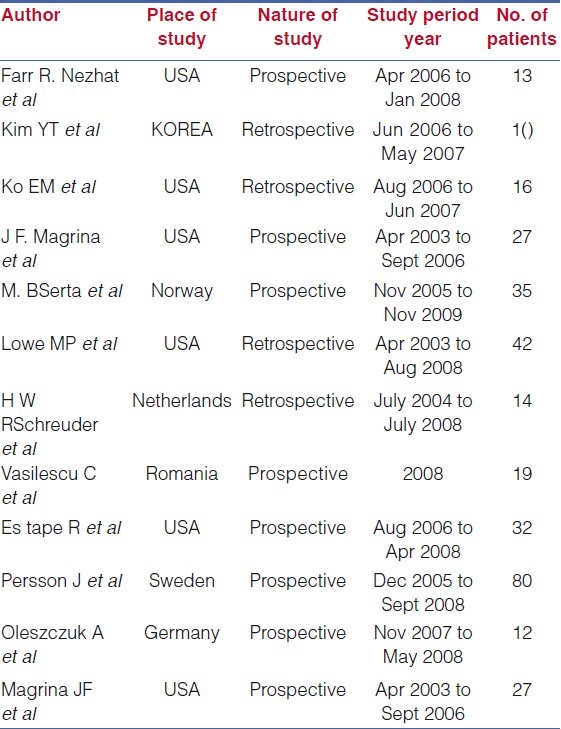

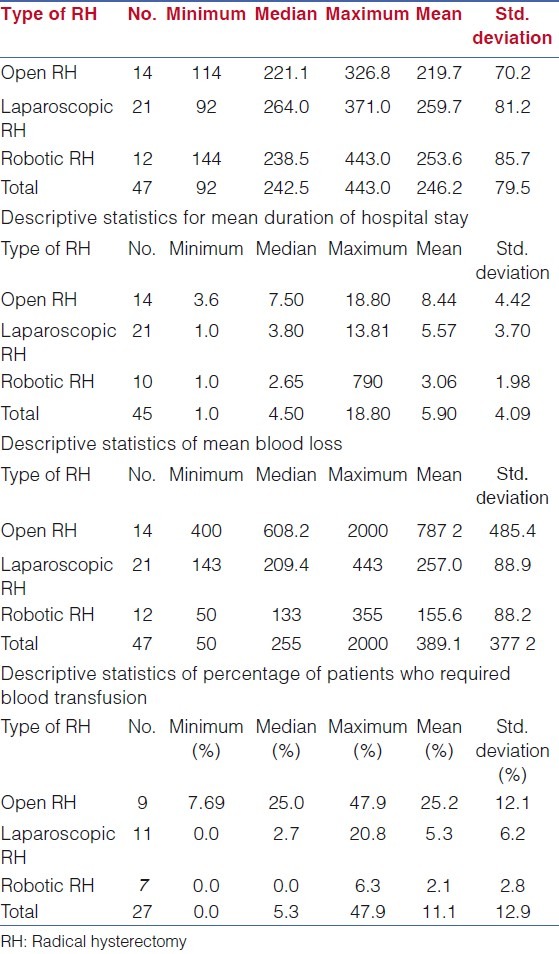

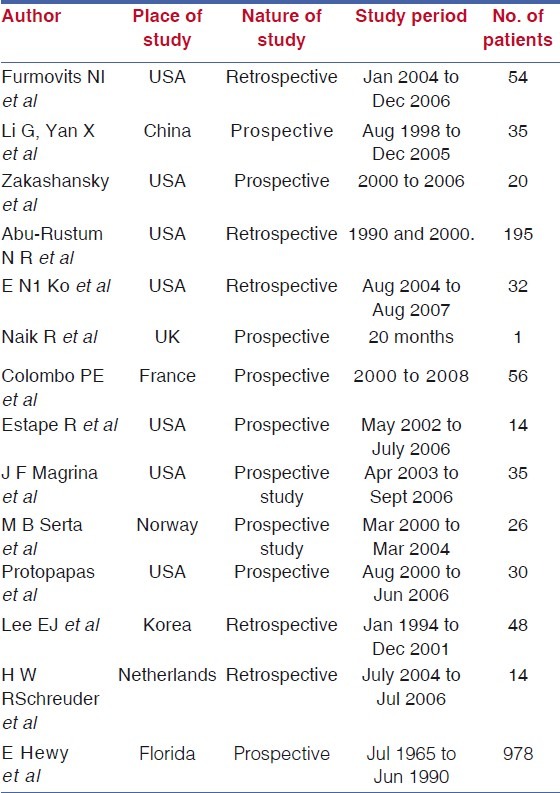

There were 21 studies (1339 patients) of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, 14 open radical hysterectomy (1552 patients) and 12 robotic radical hysterectomy (327 patients) [Tables 1–3]. Among these, 29 (60%) were prospective studies, and 40% were retrospective studies. Mean sample size across the three types of RH studies were similar. ANOVA F (2, 44) = 1.02; P = 0.367. Mean age of patients and mean body mass index across the three types of RH studies were similar. (ANOVA F (2, 39) = 1.21; P = 0.309 and ANOVA F (2, 20) = 1.20; P = 0.322 respectively). Mean operation time across the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 44) = 1.1; P = 0.330. Though laparoscopic and robotic RH appear to take more time compared to open RH, the difference was not big enough to be statistically significant. Mean blood loss (ml) for the three types of RH studies was different. ANOVA F (2, 44) = 21.6; P < 0.001. Mean blood loss was significantly higher in open RH operation compared to both laparoscopic and robotic RH. The difference in blood loss between laparoscopic and robotic RH was not statistically significant. Both laparoscopic and robotic RH had significantly lower proportion of patients with blood transfusion compared to open method. (ANOVA F (2, 24) = 20.5; P<0.001). Although the robotic RH appears to require less blood transfusion, the difference between transfusion percentages between laparoscopic and robotic RH is not big enough to be statistically significant. Duration of stay in hospital for robotic RH was significantly less than that of open RH (ANOVA F (2, 42) = 6.44; P = 0.004). All the other pair-wise differences were not big enough to be statistically significant. The linear trend also is statistically significant, F (1, 42) = 12.86; P<.001 [Table 4].

Table 1.

Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy studies

Table 3.

Robotic radical hysterectomy studies

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for mean operating time

Table 2.

Open radical hysterectomy studies

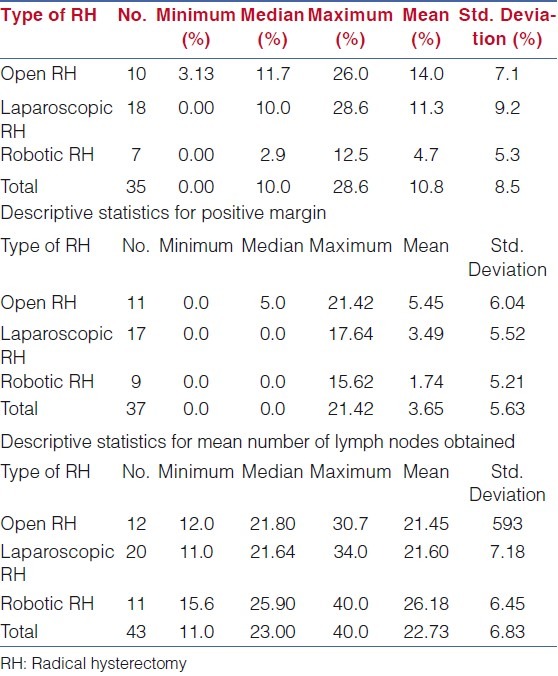

Regarding oncological outcome, mean nodal metastasis across the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 32) = 2.85; P = 0.073. Mean positive margin (%) across the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 34) = 1.10; P = .345. Positive margin was zero in all except one study pertaining to robotic RH. Mean number of lymph nodes obtained across the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 40) = 1.98; P = 0.152 [Table 5].

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for nodal metastasis

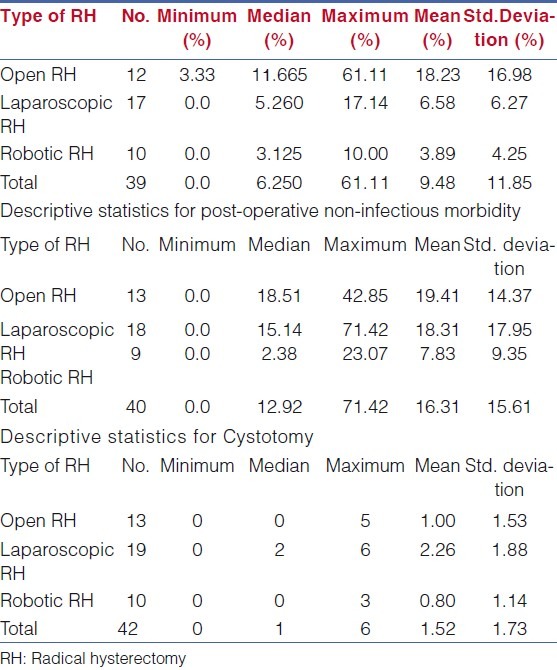

Mean percentage of patients with infectious morbidity for the three types of RH studies was also different. ANOVA F (2, 36) = 6.24; P = 0.005. Post-operative infectious morbidity was significantly higher among patients who underwent open RH compared to the other two methods. The difference in infectious morbidity between laparoscopy and robotic RH was well within chance fluctuations. Mean percentage of patients with non-infectious morbidity for the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 37) = 1.80; P = 0.179. Not even a single case of bowel injury was reported among patients who underwent robotic RH. Bowel injury was reported in 3/13 open RH and 5/19 laparoscopic RH studies. Mean number of patients with ureteric injury for the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 39) = 1.21; P = 0.309. Ureteric injury was reported in 7/13 (53.8%), 6/19 (31.6%) and 2/10 (20%) of ARH, LRH and RRH studies, respectively. Mean number of cystotomy for the three types of RH studies was different. ANOVA F (2, 39) = 3.62; P = 0.036. The difference between mean cystotomy between ARH and LRH was statistically significant [Table 6]. Cystotomy was reported in 16/19(84.21%) studies in LRH, while it is 6/13(46.15%) in ARH and 4/10(40%) in RRH. Vessel injury was reported in 6/19(31.57%), 5/13(38.46%) and 0/10 (0%) studies in LRH, ARH and RRH respectively. Conversion to laparotomy was reported in 9/20 studies of laparoscopic RH, while the same was reported in one study out of 10 reports of robotic RH.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics for post-operative infectious morbidity

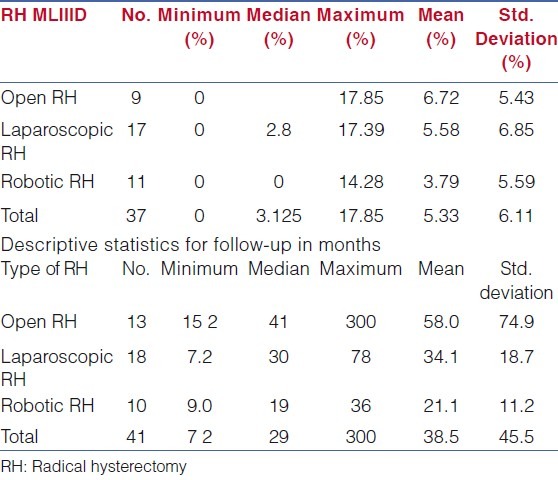

Recurrence percentage for the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 34) = 0.58; P = 0.564. Follow-up period for the three types of RH studies was similar. ANOVA F (2, 38) = 2.13;–.133 [Table 7]. Though the follow-up period for open RH was relatively high, the ANOVA resulted in non-significant result, probably due to small sample size and relatively higher standard deviation for the open RH group.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics for recurrence percentage

DISCUSSION

The current evidence shows that minimally invasive surgery is associated with less morbidity compared with open surgery and can be considered as an alternate option for surgical management of cervical cancer without compromising the oncologic outcome. There are several studies in literature, which compared laparoscopic or robotic surgeries with open method. In majority of the studies, the operating time for laparoscopy was higher compared with open method.[8–17] One pilot study by Ko EM, Muto MG et al, comparing robotic and open radical hysterectomy showed significantly higher mean operative time for robotic radical hysterectomy than open radical hysterectomy (4:50 vs 3:39 h, P=0.0002).[18] Study by Lee, Kang, et al, showed that there is no difference in operating time for both abdominal and laparoscopic method.[19] Two other studies also reported no difference in operating time for open, robotic and laparoscopic methods.[20,21] Pooled data in this meta analysis suggest that there is no statistically significant difference in mean operating time between open, robotic and laparoscopic methods. In all comparative studies, laparoscopic and robotic methods were associated with shorter hospital stay when compared to open method. Mean blood loss and transfusion rates were more for open method. In a comparative study between laparoscopic and robotic radical hysterectomy, Farr R. Nezhat, MD, M. Shoma Datta et al showed that there is no difference between operating time, hospital stay, mean pelvic lymph node yield or intraoperative or postoperative complications between robotic and laparoscopic method.[21] Our meta analysis also showed similar results. Infectious morbidity and blood loss are more for open method compared to other two. The number of cystotomies and vessel injuries are slightly higher for laparoscopic method compared to open and robotic methods. Another study which compared robotic with laparoscopic and open methods by M. Bilal Serta, and Vera Abeler showed the mean operating times (skin-to-skin) for patients undergoing robot-assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (RALRH), total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (TLRH) or abdominal radical hysterectomy (ARH) were 263 ± 70, 364 ± 57 and 163 ± 26 min respectively. Patients receiving laparotomy had shortest operative time, followed by those undergoing RALRH and then laparoscopy (P<0.0001 for both).[15] Estimated blood loss was significantly reduced in robot-assisted surgeries compared to surgeries involving laparoscopy and laparotomy (82 ± 74 ml vs. 164 ± 131 ml (P<0.0001) and 595 ± 284 ml (P = 0.023), respectively.[15] Schreuder et al suggested a relatively short learning curve for robotic procedures (a learning curve of 14 cases reduced the team's total theatre time by 48%).[22] Other studies also showed advantages of robotic surgery in terms of acceptable blood loss, operating time, parametrial margins, a nodal yield.[20,23,24] However, the cost of the DaVinci robotic surgical system is a limiting factor for the development of robotic surgery. The intraoperative costs of these operations may be higher, but indirect costs in terms of reduced hospital stay and reduced complications should be taken into account.[25]

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The broad search strategy used for this meta analysis and the multitude of databases searched has reduced bias during literature search. However, certain unpublished studies could have been missed. Even though the numbers in individual cohort were of considerable size, the numbers of studies included were low. The broad search strategy used for this systematic review and the multitude of databases searched has reduced bias during literature search. Double counting and piece together data from multiple reports of the same study were avoided by juxtaposing author names, sample sizes, and outcome data. This reduced bias during inclusion. Ideally in a study design like this, it would be better to exclude observational studies with less than 20 cases. However, the precise number is a matter and case reports or very small series are also included and the impact for publication bias may be there. The data presented is a mixture of prospective and retrospective studies and comparative and non-comparative ones. The heterogeneity risk is there. The risk of selection bias by the included studies is also noticed. For example, lymph node metastases were rare when the DaVinci surgical system was used (mean 2%). This contrasts to the traditional surgery where lymph node metastasis rate was 12%. Similarly, tumour was found occasionally at the margin of a robotic or laparoscopic case (mean of 1.7%) but apparently occurred more than three times more commonly in open surgery (mean was 5.5%). One explanation chance is if the difficult cases were done using familiar open methods and easy early-cancer cases were selected for the novel new “toy”. Of particular note are the large numbers of patients in retrospective series, where the quality of data would be of more concern. In the open open radical hysterectomy group, the largest series contains approximately 2/3 of all the cases; however, this study was completed over 20 years ago. In addition, many of the laparoscopic studies significantly pre-date the robotic studies. Image quality, instrumentation and energy sources have all improved dramatically over recent years and therefore it is not possible to compare ‘like with like’.

CONCLUSION

Minimally invasive surgery is an alternate option for radical surgery in early-stage cervical cancer. However, laparoscopic method is not free from complications. Experience of surgeon may reduce complications. Robotic surgery is associated with less morbidity compared to open and laparoscopic method in this meta analysis. This may be due to better magnification, dexterity, flexibility and considerable reduction in surgeon's fatigue during surgery compared to other methods. Given the drawbacks of observational studies with their multiple inherent biases, it is difficult to see that the conclusions reached as a result of this systematic review are likely to change practice. The potential advantages of minimal access surgery techniques eg shorter hospital stay, less infectious morbidity are apparent from individual observational studies. However, because of the inherent biases relating to case selection for different surgical techniques treating the same disease, the only way to reliably look at differences between the individual techniques would be to perform randomised studies comparing the different techniques. Only studies of this type will lead to potentially valid conclusions about key oncological outcomes, quality of life and risks of major morbidity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Averette HE, Nguyen HN, Donato DM, Penalver MA, Sevin BU, Estape R, et al. Radical hysterectomy for invasive cervical cancer: A 25-year prospective experience with the Miami technique. Cancer. 1993;71(Suppl 4):1422–37. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820710407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nezhat CR, Burrell MO, Nezhat FR, Benigno BB, Welander CE. Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with para aortic and pelvic node dissection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:864–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91351-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sert BM, Abeler VM. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy (Piver type III) with pelvic node dissection-case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2006;27:531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker JL, Piedmonte M, Spirtos N, Eisenkop S, Schlaerth J, Mannel RS, et al. Atlanta, Georgia: 2006. Jun 2-6, Surgical staging of uterine cancer: Randomized phase III trial of laparoscopy compared with laparotomy-A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study [GOG]: Preliminary results [abstract]. Proceedings of the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magrina JF. Robotic surgery in gynecology. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magrina JF, Zanagnolo VL. Robotic Surgery for Cervical Cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49:879–85. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.6.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting: Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Yan X, Shang H, Wang G, Chen L, Han Y. A comparison of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy and laparotomy in the treatment of Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zakashansky K, Chuang L, Gretz H, Nagarsheth NP, Rahaman J, Nezhat FR. A case-controlled study of total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy versus radical abdominal hysterectomy in a fellowship training program. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:1075–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu-Rustum NR, Gemignani ML, Moore K, Sonoda Y, Venkatraman E, Brown C, et al. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy using the argon-beam coagulator: Pilot data and comparison to laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91:402–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frumovitz M, dos Reis R, Sun CC, Milam MR, Bevers MW, Brown J, et al. Comparison of total laparoscopic and abdominal radical hysterectomy for patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:96–102. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000268798.75353.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Protopapas A, Jardon K, Bourdel N, Botchorishvili R, Rabischong B, Mage G, et al. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy in the treatment of early cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:712–22. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3e2be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G, Yan X, Shang H, Wang G, Chen L, Han Y. A comparison of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy and laparotomy in the treatment of Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pahisa J, Martínez-Román S, Torné A, Fusté P, Alonso I, Lejárcegui JA, et al. Comparative study of laparoscopically assisted radical vaginal hysterectomy and open Wertheim-Meigs in patients with early-stage cervical cancer: Eleven years of experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:173–8. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181bf80ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sert MB, Abeler V. Robot-assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: Comparison with total laparoscopic hysterectomy and abdominal radical hysterectomy: One surgeon's experience at the Norwegian Radium Hospital. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:600–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naik R, Jackson KS, Lopes A, Cross P, Henry JA. Laparoscopic assisted radical vaginal hysterectomy versus radical abdominal hysterectomy: A randomised phase II trial: Perioperative outcomes and surgicopathological measurements. BJOG. 2010;117:746–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malzoni M, Tinelli R, Cosentino F, Fusco A, Malzoni C. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy in patients with early cervical cancer: Our experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1316–23. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko EM, Muto MG, Berkowitz RS, Feltmate CM. Robotic versus open radical hysterectomy: A comparative study at a single institution. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:425–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee EJ, Kang H, Kim DH. A comparative study of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with radical abdominal hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: A long-term follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156:83–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estape R, Lambrou N, Diaz R, Estape E, Dunkin N, Rivera A. A case matched analysis of robotic radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy compared with laparoscopy and laparotomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:357–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nezhat FR, Datta MS, Liu C, Chuang L, Zakashansky K. Robotic radical hysterectomy versus total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for treatment of early cervical cancer. JSLS. 2008;12:227–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreuder HW, Zweemer RP, van Baal WM, van de Lande J, Dijkstra JC, Verheijen RH. From open radical hysterectomy to robot-assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer: Aspects of a single institution learning curve. Gynecol Surg. 2010;7:253–8. doi: 10.1007/s10397-010-0572-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geisler JP, Orr CJ, Khurshid N, Phibbs G, Manahan KJ. Robotically assisted laparoscopic radical hysterectomy compared with open radical hysterectomy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:438–42. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181cf5c2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nam EJ, Kim SW, Kim S, Kim JH, Jung YW, Paek JH, et al. A case-control study of robotic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy using 3 robotic arms compared with abdominal radical hysterectomy in cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:1284–9. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ef0a14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasilescu C, Sgarbura O, Tudor S, Popa M, Turcanu A, Florescu A, et al. Robotic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy: Our early experience. Chirurgia. 2009;104:393–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]