Abstract

Aim:

The aim was to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) regarding breast self-examination (BSE) in a cohort of Indian female dental students.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive questionnaire study was conducted on dental students at Panineeya Institute of Dental Sciences, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 12). Chi-square test was used for analysis of categorical variables. Correlation was analyzed using Karl Pearson's correlation coefficient. The total scores for KAP were categorized into good and poor scores based on 70% cut-off point out of the total expected score for each. P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

This study involved a cohort of 203 female dental students. Overall, the total mean knowledge score was 14.22 ± 8.04 with the fourth year students having the maximum mean score (19.98 ± 3.68). The mean attitude score was 26.45 ± 5.97. For the practice score, the overall mean score was 12.64 ± 5.92 with the highest mean score noted for third year 13.94 ± 5.31 students. KAP scores upon correlation revealed a significant correlation between knowledge and attitude scores only (P<0.05).

Conclusion:

The study highlights the need for educational programs to create awareness regarding regular breast cancer screening behavior.

Keywords: Breast self-examination, Dental students, India, Knowledge, Practice

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a global health issue and a leading cause of death among women internationally.[1–3] In India, it accounts for the second most common cancer in women. Around 80,000 cases are estimated to occur annually. The age-standardized incidence rate of breast cancer among Indian women is 22.9 and the mortality rate is 11.19.[4] In the present scenario, roughly 1 in 26 women are expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime.[5]

Breast cancer is distinguished from other types of cancer by the fact that it occurs in a visible organ and be detected and treated at an early stage.[6]. The 5-year survival rate reached to 85% with early detection whereas later detection decreased the survival rate to 56%.[7] The low survival rates in less developed countries can be attributed to the lack of early detection as well as inadequate diagnosis and treatment facilities.

Recommended preventive techniques to reduce breast cancer mortality and morbidity include breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE), and mammography.[8] CBE and mammography require hospital visit and specialized equipment and expertise whereas BSE is an inexpensive tool that can be carried out by women themselves.[9] BSE benefits women in two ways: women become familiar with both the appearance and the feel of their breast and detect any changes in their breasts as early as possible.[10] In the literature, it is stated that 90% of the times breast cancer is first noticed by the person herself.[11] Also, several studies have shown that barriers to diagnosis and treatment can be addressed by increasing women's awareness of breast cancer.[12,13]

Even though BSE is a simple, quick, and cost-free procedure, the practice of BSE is low and varies in different countries; like in England, a study by Philip et al.[14] reported that only 54% of the study population practised BSE. Furthermore, in Nigeria, the practice of BSE ranged from 19% to 43.2%,[9,15] and in India, it varied from 0 to 52%.[16,17] Several reasons like lack of time, lack of self-confidence in their ability to perform the technique correctly, fear of possible discovery of a lump, and embarrassment associated with manipulation of the breast have been cited as reasons for not practising BSE.[18,19]

With this background, the present study was designed to determine the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) regarding BSE in a cohort of Indian female dental students.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted on dental students at Panineeya Institute of Dental Sciences, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India, among female dental students regarding their knowledge, attitude and practice of BSE.

Participation was on voluntary basis. Anonymity and confidentiality of the responses was assured. Ethical committee clearance from the institutional data review board was obtained.

Data were collected by a self-administered pretested close-ended questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised 35 items (15 items on knowledge, 13 items on attitude, and 7 items on practice). For knowledge items, categorical responses (true/false/don’t know) were applied, for attitude items, 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree/agree/neutral/not agree/strongly disagree) was used, and for practice, similar ordinals (never/seldom/neutral, frequent/always) was applied.

For positive knowledge, item score “2” was used for correct responses, “1” for don’t know, and “0” for incorrect response. For a positive attitude item, a score of “4,” “3,” “2,” “1,” and “0” was used for strongly disagree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree respectively. For practice, an item score of “0,” “1,” “2,” “3,” and “4” was given for never, seldom, neutral, frequently, and always, respectively. Overall, the score was reversed for all the negative items.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 12). Categorical variables were described using frequency distribution and percentages. Continuous variables were expressed by means and standard deviations. Multiple group analysis was done by ANOVA and Newman–Keuls multiple post-hoc tests. Chi-square test was used for analysis of categorical variables. Correlation was analyzed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. The total scores for KAP were categorized into good or poor based on 70% cut-off point out of the total expected score for each. p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

This study involved a cohort of 216 female dental students, out of whom, 203 completed the questionnaire (response rate, 93.98%). The reliability of the questionnaire was 0.8. The age range of the study population was 17–22 years with a mean age of 19.6 ± 1.38 years.

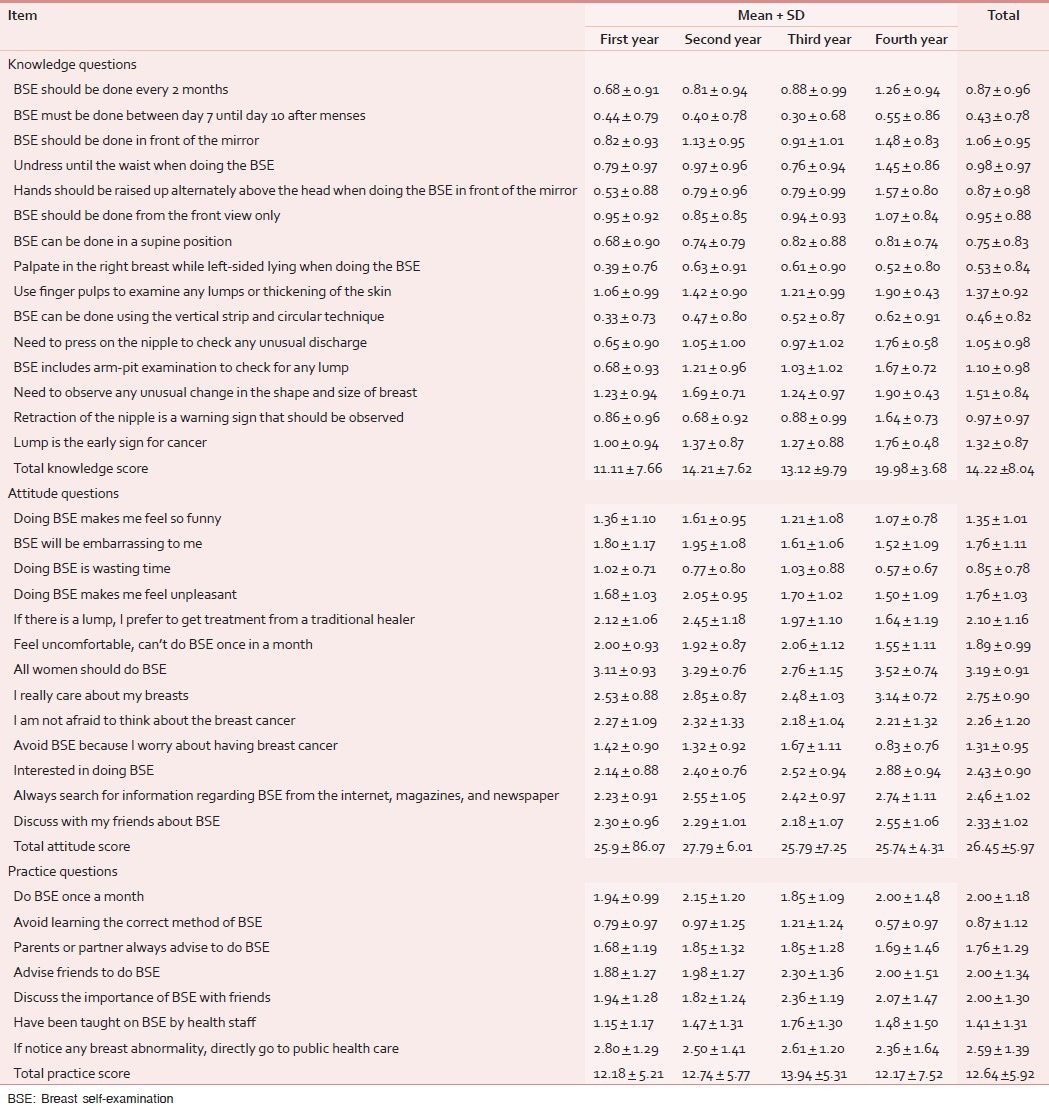

Overall, the total mean knowledge score was 14.22 ± 8.04 with the fourth year students having the maximum mean score (19.98 ± 3.68). The knowledge on “need to observe any unusual change in the shape and size of breast” had the highest mean score for all the students (1.51 ± 0.84), and also accounted for the highest knowledge in the first year (1.23 ± 0.94), second year (1.69 ± 0.71), and fourth year (1.90 ± 0.43). Among the third year students, majority identified “lump is the early sign for cancer” (1.27 ± 0.88), whereas among the fourth year students, “use of finger pulps to examine any lumps or thickening of the skin” had the highest mean knowledge score. On the whole, when the lowest mean knowledge score was considered, it was noted that “BSE must be done between day 7 until day 10 after menses” had the least mean score of 0.43 ± 0.78, which was also the lowest among second year and third year students (0.40 ± 0.78 and 0.30 ± 0.68, respectively). For the first year students, the lowest score was observed for “BSE can be done using vertical strip and circular technique” (0.33 ± 0.73), and for fourth year students, it was for “palpate in the right breast while left-sided lying when doing the BSE.”

Though the attitude score was the best among all (mean attitude score was 26.45 ± 5.97), it was strikingly low among fourth year students who had the maximum knowledge score. The highest overall attitude score was seen for second year students (27.79 ± 6.01). All the participants felt that “all women should do BSE” which had the highest overall mean score of 3.19 ± 0.91 and also for individual years (first year, 3.11 ± 0.9; second year, 3.29 ± 0.76; third year, 2.76 ± 1.15; fourth year, 3.52 ± 0.74). Likewise, “doing BSE is wasting time” had the least overall mean score (0.85 ± 0.78) and also the least mean score for all the years.

For the practice score, the overall mean score was 12.64 ± 5.92 with the highest mean score noted for third year students, 13.94 ± 5.31. The highest practice score for all individual years and overall was for “if notice any breast abnormality, directly go to public health care” (overall mean score, 2.59 ± 1.39). The least score was recorded for “avoid learning the correct method of BSE” (0.87 ± 1.12). The practice score was comparatively low in second and fourth year students with a higher/better knowledge score [Table 1].

Table 1.

Mean scores for knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self-examination among various years

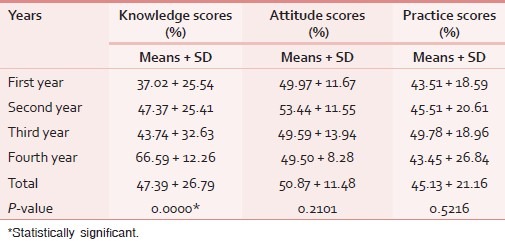

When mean percent scores were considered, the highest mean percent for knowledge was among fourth year students (66.69 ± 12.26) and this difference was statistically significant when compared to other years (P = 0.000). The mean percent of attitude score was maximum for second year students, 53.44 ± 11.55. However, on comparison, no significant difference was noted among various years (P = 0.21). Similarly, even the mean percent of practice score did not reveal any significant difference among various years (mean Percent, 45.13 ± 21.16; P = 0.52; Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of mean percent scores among various years with respect to knowledge, attitude, and practice scores

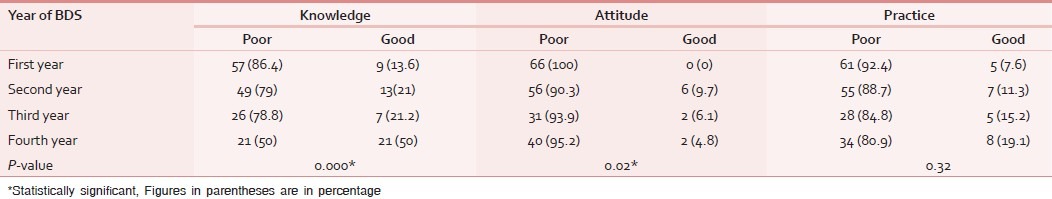

On the whole, when good score (i.e., a score of 70% or more of the total) was regarded, a good knowledge and practice score was observed among fourth year students (50% and 19.1%, respectively); for attitude, it was seen among second year students (9.7%). Majority of the population had poor KAP scores. Good knowledge and attitude toward BSE only had a statistically significant difference [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of the knowledge, attitude, and practice between the years of study

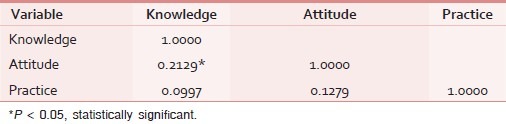

KAP scores upon correlation revealed a significant correlation between knowledge and attitude scores only (P < 0.05; Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between knowledge, attitude, and practice scores

DISCUSSION

With the incidence of breast cancer rising, and also absence of any established national breast screening in India, it becomes important to assess the knowledge and practice of BSE in various age groups. The present study involved female dental students (aged 17–24 years) as it can motivate them and instill in them preventive health behavior of practising BSE regularly. Besides, being a part of a health-care-providing team, they can disseminate information to patients as well as family and friends.

Due to the lack of an international standardized questionnaire on KAP of BSE, we employed the questionnaire utilized in the study by Rosmawati;[20] nevertheless, the questionnaire was pretested on this group and the reliability was found to be good (0.8).

The overall knowledge of BSE in this population was rather very poor. This finding was consistent with the study done by Yadav and Jaroli[17] among Indian college-going students in Rajasthan wherein 28% examined their breasts rarely or never. This poor knowledge reflects on the fact that adequate public education is essential to facilitate early detection of breast cancer.

When the attitude toward BSE was analyzed, it was noted that the majority of the population felt that “all women should do BSE” (mean, 3.19 ± 0.91) suggesting the importance of self-examination in early diagnosis of breast cancer. Though only 20.6% of the population had a good attitude score, the overall mean percent scores for attitude component was the highest indicating that there is an urge among this group to inculcate positive health behavior. Moreover, the finding of this study reveals that the present study population is more enthusiastic to gain information and interested in doing BSE, which contrasts with the findings of previous studies wherein unpleasantness and fear were potential barriers for practising BSE.[21,22]

The practising of BSE in this group of Indian dental students was also quite alarmingly low (mean score, 12.64 ± 5.92). The mean percent of population practising BSE was 45.13 ± 21.16. Though only 53% of them had a good BSE practice score, this was a much better finding as compared to teenagers (3.4%) and 17–30 year olds (14.8%) in Europe.[20] Also, contrasting results were noted when comparisons were made with various populations like 28.3% of Pakistani[23] females practised BSE and 32.1% of Nigerian females performed BSE.[15] Among the health-care providers, around 90.3% performed BSE in Sao Paulo,[24] and in Turkey,[25] 28% of the nurses and 32% of physicians did not practise BSE. Likewise, in a study by Haji-Mahmoodi et al,.[26] it was determined that most health-care practitioners (63–72%) did not practice BSE.

Our study revealed a positive correlation between knowledge and practice (correlation coefficient, 0.2129; P < 0.05) illustrating the desire among this population to acquire correct knowledge regarding BSE. Also, this finding brings to light that if awareness and health education programs are conducted, it might result in negative behaviors changing to positive healthy practices.

The present study points out to a number of conclusions. Though, this study was carried out on a health-care-providing team of dental students, the knowledge and practice of BSE was quite low. The study also highlights the need for educational programs to create awareness regarding regular breast cancer screening behavior. In this present population, most of them obtained information in the dental school; therefore, it is vital to update them with important health issues that are not often a part of their course.

Our study also has several limitations. The sample of the study population includes female dental students; hence, the results of the study cannot be generalized to a larger population in India. Likewise, the survey was conducted on a health-care-providing team; hence, the study group might be better informed. Even though the questionnaire utilized in the study was pretested, it may limit the comparability of our results with other studies. Furthermore, the data were collected by self-report, which may be a source of bias. Also, since this study was limited to only female dental students of a dental school, the sample size is relatively small and may not be representative of all females of that age group; hence, it is recommended to conduct further studies using larger samples at various institutions in India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Althuis MD, Dozier JM, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Brinton LA. Global trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality 1973-1997. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:405–12. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shibuya K, Mathers CD, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJ. Global and regional estimates of cancer mortality and incidence by site: II. Results for the global burden of disease 2000. BMC Cancer. 2002;2:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-2-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hortobagyi GN, de la Garza Salazar J, Pritchard K, Amadori D, Haidinger R, Hudis CA, et al. The global breast cancer burden: Variations in epidemiology and survival. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005;6:391–401. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2005.n.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GLOBOCAN 2008 (IARC) Section of Cancer Information. [Last accessed on 2011 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/populations/factsheet.asp .

- 5.Raina V, Bhutani M, Bedi R, Sharma A, Deo SV, Shukla NK, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of early breast cancer at a major cancer center in North India. Indian J Cancer. 2005;42:40–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.15099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tasci A, Usta YY. Comparison of Knowledge and Practices of Breast Self Examination (BSE): A Pilot Study in Turkey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1417–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallal JC. The relationship of health beliefs, health locus of control, and self concept to the practice of breast self-examination in adult women. Nurs Res. 1982;31:137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, Woolf SH. Breast cancer screening: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:347–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-5_part_1-200209030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okobia MN, Bunker CH, Okonofua FE, Osime U. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Nigerian women towards breast cancer: A cross-sectional study. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karayurt O, Ozmen D, Cetinkaya AC. Awareness of breast cancer risk factors and practice of breast self examination among high school students in Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:359. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simsek S, Tug T. Benign tumors of the breast: Fibroadenoms. Sted. 2002;11:102–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagerlund M, Hedin A, Sparén P, Thurfjell E, Lambe M. Attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge as predictors of nonattendance in a Swedish population-based mammography screening program. Prev Med. 2000;31:417–28. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMichael C, Kirk M, Manderson L, Hoban E, Potts H. Indigenous women's perceptions of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24:515–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2000.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philip J, Harris WG, Flaherty C, Joslin CA. Clinical measures to assess the practice and efficiency of breast self-examination. Cancer. 1986;58:973–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860815)58:4<973::aid-cncr2820580429>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gwarzo UM, Sabitu K, Idris SH. Knowledge and practice of breast-self examination among female undergraduate students of Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, northwestern Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2009;8:55–8. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta SK. Impact of a health education intervention program regarding breast self examination by women in a semi-urban area of Madhya Pradesh, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:1113–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yadav P, Jaroli DP. Breast cancer: Awareness and risk factors in college-going younger age group women in Rajasthan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:319–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stillman MJ. Women's health beliefs about breast cancer and breast self-examination. Nurs Res. 1977;26:121–7. doi: 10.1097/00006199-197703000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lierman LM, Young HM, Powell-Cope G, Georgiadou F, Benoliel JQ. Effects of education and support on breast self-examination in older women. Nurs Res. 1994;43:158–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosmawati NH. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of breast self-examination among women in a suburban area in Terengganu, Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1503–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hisham AN, Yip CH. Overview of breast cancer in Malaysian women: A problem with late diagnosis. Asian J Surg. 2004;27:130–3. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salazar MK. Breast self-examination beliefs: A descriptive study. Public Health Nurs. 1994;11:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1994.tb00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilani SI, Khurram M, Mazhar T, Mir ST, Ali S, Tariq S, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of a Pakistani female cohort towards breast cancer. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carelli I, Pompei LM, Mattos CS, Ferreira HG, Pescuma R, Fernandes CE, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self-examination in a female population of metropolitan São Paulo. Breast. 2008;17:270–4. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavdar Y, Akyolcu N, Ozbaş A, Oztekin D, Ayoğu T, Akyüz N. Determining female physicians’ and nurses’ practices and attitudes toward breast self-examination in Istanbul, Turkey. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:1218–21. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1218-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haji-Mahmoodi M, Montazeri A, Jarvandi S, Ebrahimi M, Haghighat S, Harirchi I. Breast self-examination: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices among female health care workers in Tehran, Iran. Breast J. 2002;8:222–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]