Abstract

Purpose:

To develop an integrated diabetic retinopathy screening program that uses telemedicine.

Materials and Methods:

In this evaluation of diagnostic technology, six telemedical screening units were established to cover all regions of Bahrain. The units were equipped with a digital fundus camera at the primary health care clinic. Fundus photographs were transmitted via the Internet to a centralized reading center. A retinal specialist at the reading center assessed the images.

Results:

From 2003 to 2009, 17,490 diabetic patients were screened. Of the screened patients, 20% were diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy. Of these cases, 31% required treatment.

Conclusion:

Telemedicine-based screening program is a feasible and efficient means of detecting diabetic retinopathy and providing treatment.

Keywords: Diabetic Retinopathy, Primary Care, Screening, Telemedicine

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a leading cause of visual disability and blindness worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of diabetes in the Eastern Mediterranean region is estimated to be between 5% to 15%.1 In Bahrain, the number of diabetics is 150,0002 and the prevalence is 14%.3

In a 1997 population-based visual disability survey in Bahrain using WHO standard methodology, 2426 cases were examined. The results indicated that DR is a major cause of disability, accounting for 6% of cases.4 An established protocol for screening DR is needed to improve the management of diabetic eye disease and to prevent blindness. Therefore, the institution of an efficient screening program directed toward detecting patients at risk is an urgent priority.

The main goal of this project was to develop an integrated screening program within Bahrain's healthcare system to provide quality DR screening for early detection and management through an organized system of primary, secondary, and tertiary facilities to provide optimum care for diabetics.

We began with a pilot telemedicine project for a period of 1 year from January through December 2003. A screening unit was established at the Muharraq Health Center, Bahrain, for this purpose. The aim was to study the technical feasibility as well as the value of introducing a telemedicine screening program.

Bahrain has a population of 1,105,5092 and is divided into five governorates. Bahrain has well-integrated primary, secondary, and tertiary health care systems. Primary health care is provided by the government through 22 primary health care centers. In each governorate, there is one regional and several other health care centers.

Following the evaluation and success of the pilot project, the program was expanded to other regional health care centers to cover the total population of the five governorates. By 2008, the total number of units was six. Five units are now established at health care centers and one unit at the Diabetic Outpatient Clinic at Salmaniya Medical Complex (SMC), the main referral hospital. The cumulative results of the program are based on data obtained from January 2003 through December 2009.

The entire program is a collaborative effort between the Ministry of Health, the National Committee for the Prevention of Blindness, and a non-governmental organization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

There are six established DR units. Diabetic patients are referred to the units from all regions. Diabetes specialist nurses recorded the data from each patient on a DR Screening Card [Figure 1]. The data in the pilot study included demographic information, family physician details, diabetes and ophthalmological history, visual acuity, and fundus examination results. The data from 2003 to 2009 included the distribution of DR and associated ophthalmic conditions among the diabetic patients screened. The eyes of each patient were dilated with 1% topical tropicamide to obtain a clear fundus photograph.

Figure 1.

Diabetic Screening Card

Each unit is equipped with a Canon CR6 45NM non-mydriatic digital camera connected to a computer. Single-field 45° fundus photos were obtained by a trained ophthalmic technician, who was instructed to recapture any images of poor quality at the same sitting. The single-field 45° photograph was centered on a point halfway between the temporal edge of the optic disc and the fovea. The images were transferred electronically through the Internet to the reading center at the Ophthalmology Department at the SMC. The photographs were categorized by an ophthalmologist as no diabetic retinopathy (NDR) and diabetic retinopathy (DR). An ophthalmologist at the center diagnosed and graded the images. Patients with retinopathy were requested to return for further evaluation and treatment as warranted. On examination, retinopathy cases were classified according to the international classification of DR: no retinopathy, mild DR, moderate DR, or severe DR, nonproliferative DR (NPDR), and proliferative DR.5 Those who did not require treatment were referred back for further digital photography follow-up appointments at the individual health centers.

The study received written approval and ethical approval from the Ministry of Health Medical Research Committee.

RESULTS

The pilot project included data of 736 diabetic patients; 49% were women and 51% were men. The age range was 24–84 years, with a mean age of 53 years. The diabetic history indicated that 25 (4%) of the patients had Type I diabetes; 654 (89%) had Type II diabetes, and 7% had diet controlled diabetes. Almost a third of the patients had hypertension (232, 32%). Almost all [708 (96%)] of the patients were under primary care; 2 (1%) were under secondary care; and 24 (3%) were under shared care.

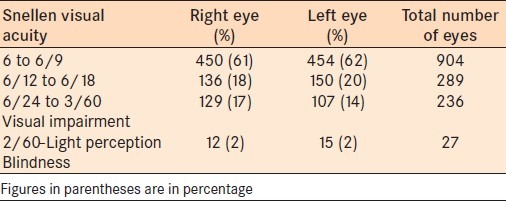

The visual acuity distribution for each eye in the pilot project is shown in Table 1. The majority of patients had normal visual acuity (6/6 to 6/9). Approximately 20% of patients were visually impaired or blind in at least one eye (6/24 or worse). The vast majority (90%) of the fundus photographs were of good quality for interpretation.

Table 1.

Visual acuity in the pilot project cases

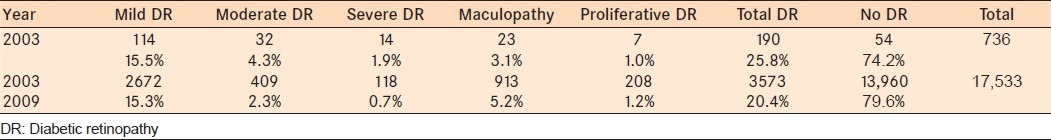

Table 2 shows the distribution of the different retinopathy classifications for the pilot project in 2003 and the total for 2003–2009. Of the total number of diabetic patients screened, DR was detected in 25.8% of cases in 2003 and in 20.4% of the cases in 2003–2009. Concurrent ophthalmic conditions in the patients in the pilot project were 29 cases of cataract, 6 cases of advance optic nerve disc cupping, 4 cases of pale disc, 4 cases of vitreous hemorrhage, 3 cases of chorioretinal scar, 1 case of macular hole, and 1 case of central retinal vein occlusion. The ophthalmic conditions of the patients from 2003 to 2009 included 326 (1.9%) cases of cataract, 225 (1.3%) cases of advanced optic disc cupping, 64 (41.0%) cases of vitreous hemorrhage, 54 (0.3%) cases of chorioretinal scars, 197 (1.1%) cases of drusen, 12 (0.07%) cases of central retinal vein occlusion, 16 (0.09%) cases of retinal pigment epithelial changes, and 13 (0.13%) cases of myelinated nerve fibers.

Table 2.

Distribution of the screened cases of diabetic retinopathy for the pilot project

DISCUSSION

To justify the DR screening project, a pilot diabetic screening unit using digital fundus photographs to screen a large number of patients and sending images through the Internet was initiated and the results of this pilot study project indicated the effectiveness and feasibility of moving forward with the complete DR screening project. This screening program is a suitable method for detecting and grading DR in a non-selected diabetic population so that laser treatment can be performed at an optimal time in all patients with diabetes.6–9 Ophthalmologists and primary care physicians can share digital retinal images of their patients, which will improve patient treatment. Using an ophthalmologist at a reference center to diagnose and grade the digital images saves valuable time. While in most previous studies7–9 trained readers interpreted the retinal image photographs, in the present study ophthalmologists interpreted the retinal image photographs.

Single fundus photographs, however, can serve as an effective screening tool for DR when they are used to identify patients with retinopathy for referral for more complete ophthalmic evaluation and management, and they can be used as a more cost-effective means of screening for DR, which has been documented by other studies.10–12 However, the single fundus photographs are of limited value for the diagnosis of macular edema.12

In this project, the majority of patients with diabetes received their care in a primary care setting. Most primary care physicians have neither the expertise nor the equipment necessary to accurately screen for DR. Moreover, they are overloaded with high patient volume at their clinics. Applying screening tools at the primary care setting will improve patient compliance and be useful for training family physicians to screen images at the same time to identify some other common eye abnormalities, which will facilitate the screening process and help to prevent blindness.6,7 Information technology infrastructure at the Ministry of Heath where all the primary and secondary care center systems are connected by the Internet, as well as the advances in technology instituted by the government at Bahrain facilitated this telemedicine approach and can be implemented in other specialties, which is an excellent and feasible approach for screening and treating patients for many other disease modalities in Bahrain.

The project successfully screened diabetic patients for DR. The percentage of patients with DR from all regions of Bahrain was 20.4%, which is similar to that reported in many studies in which screening was performed with a digital camera.10–12 The number of patients receiving this service at the health care centers is increasing, but still they do not represent the expected number of diabetic patients, and this can be improved through patient education and promotion of the program.

CONCLUSION

The use of digital images was an efficient method for diagnosing and classifying DR. Digital photography was useful for creating a network of several screening centers organized around a central ophthalmological reading center. Digital imaging is important for community screening of blinding eye diseases such as glaucoma, cataract, and DR. The data indicate that a screening program for DR is feasible and justified to prevent blindness in patients with diabetes. An initial investment in professional and material resources is required for this program. This project represents a collaborative effort between primary care physicians and ophthalmologists for effective screening and timely treatment.

Recommendations and future plans include grading, follow-up of cases by family physicians through established guidelines, the use of full-time trained personnel to operate the digital camera for sustainability of the program, clinical workshops for primary care physicians to reinforce concepts, and the establishment of additional regional screening units.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO EMRO web site strategies for diabetes control and prevention. [Last accessed on 2011 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/ncd/pdf/Diabetes_in_EMRO.pdf .

- 2. Estimated Population 2008, Central informatics organization, Kingdom of Bahrain.

- 3.National non communicable Diseases Risk factors Survey. Kingdom of Bahrain: Ministry of Health; 2007. [Under publication] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed A, Al-Alawi E, Fateha B, Sibai A. Population based visual disability and visual impairment survey in Bahrain. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2002;16:279–87. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL, 3rd, Klein RE, Lee PP, Agardh CD, Davis M, et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scale. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1677–82. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maberley D, Walker H, Koushik A, Cruess A. Screening for diabetic retinopathy in James Bay, Ontario: A cost-effectiveness analysis. CMAJ. 2003;168:160–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luzio S, Hatcher S, Zahlmann G, Mazik L, Morgan M, Liesenfeld B, et al. Feasibility of using the TOSCA telescreening procedures for diabetic retinopathy. Diabet Med. 2004;21:1121–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchinson A, McIntosh A, Peters J, O’Keeffe C, Khunti K, Baker R, et al. Effectiveness of screening and monitoring tests for diabetic retinopathy-A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2000;17:495–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maberley D, Cruess AF, Barile G, Slakter J. Digital photographic screening for diabetic retinopathy in the James Bay Cree. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2002;9:169–78. doi: 10.1076/opep.9.3.169.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vleming EN, Castro M, López-Molina MI, Teus MA. [Use of non-mydriatic retinography to determine the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in diabetic patients] Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2009;84:231–6. doi: 10.4321/s0365-66912009000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boucher MC, Nguyen QT, Angioi K. Mass community screening for diabetic retinopathy using a nonmydriatic camera with telemedicine. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005;40:734–42. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(05)80091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liesenfeld B. A telemedical approach to the screening of diabetic retinopathy: Digital fundus photography. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:345–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]