Abstract

Two asymptomatic elderly women who underwent cataract extraction 7 or more years previously and with intraocular lens placement presented with a linear bead-like white multinodular mass in the inferior angle simulating iris metastasis versus large inflammatory precipitates. There was no iris infiltration. In the first case, the posterior lens capsule was intact and there was no evidence of gelatinous vitreous in the anterior chamber, whereas in the second case, the capsule was open and there was gelatinous vitreous prolapse. In both cases, there was asteroid hyalosis in the vitreous. Both patients were diagnosed with prolapsed vitreous asteroid hyalosis into the anterior chamber and managed with observation. Vitreous asteroid hyalosis can prolapse into the anterior chamber of pseudophakic elderly patients with or without capsular opening and can simulate an intraocular tumor.

Keywords: Anterior Chamber, Asteroid Hyalosis, Iris, Metastasis, Prolapse, Vitreous

INTRODUCTION

Asteroid hyalosis of the vitreous is found in 1.2% of the population, according to the Beaver Dam Eye Study.1 This condition is more frequent with aging as it is found in 0.2% of 43- to 54-year-old patients and in 2.9% of 75- to 86-year-old patients.1 This degenerative condition appears clinically as yellow-white spherical bodies floating in the vitreous gel in chains or sheets, without visual compromise. Histopathologically, the bodies show positive staining for calcium and lipids. The pathogenesis of asteroid hyalosis is poorly understood, but it is more frequent in males, patients with higher body mass, and those with greater alcohol consumption.1

Asteroid hyalosis remains confined to the vitreous without anterior chamber involvement. Often there is a posterior vitreous detachment without asteroid bodies.2 In a review of published case reports and series in the English language literature involving 386 affected patients in total study population of 27,948 persons,1–4 we noted only one case of asteroid hyalosis prolapse into the anterior chamber.5 In this report, we describe two patients with prolapse of asteroid hyalosis into the anterior chamber, simulating metastasis.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

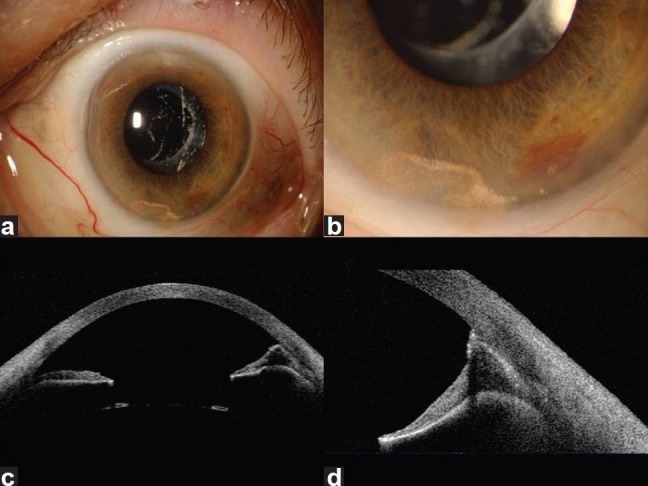

A 90-year-old Caucasian woman was found to have a multinodular white iris mass in the left eye (OS) and was referred for iris metastasis. Seven years previously she had uncomplicated cataract extraction with placement of posterior chamber intraocular lens. There was no history of postcataract iritis. There was no history of trauma or cancer. Visual acuity was 20/30 the right eye (OD) and 20/70 in the left eye (OS). There were white linear multilobular lesions in the inferior anterior chamber angle [Figure 1]. The cornea was clear without precipitates and the posterior capsule was intact. There was no gelatinous vitreous prolapse. Vitreous asteroid hyalosis was noted. The fundus was otherwise unremarkable. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) disclosed iridoendothelial adhesion inferiorly with multifocal dense opacities causing posterior shadowing, consistent with calcification. These findings were consistent with asteroid hyalosis in the anterior chamber. Observation was advised.

Figure 1.

A 90 year-old asymptomatic woman was referred for a circumscribed white iris mass (a) that proved on examination to be linear asteroid bodies (b) and showed iris endothelial adhesion (c) with calcified shadowing on anterior segment optical coherence tomography (d)

Case 2

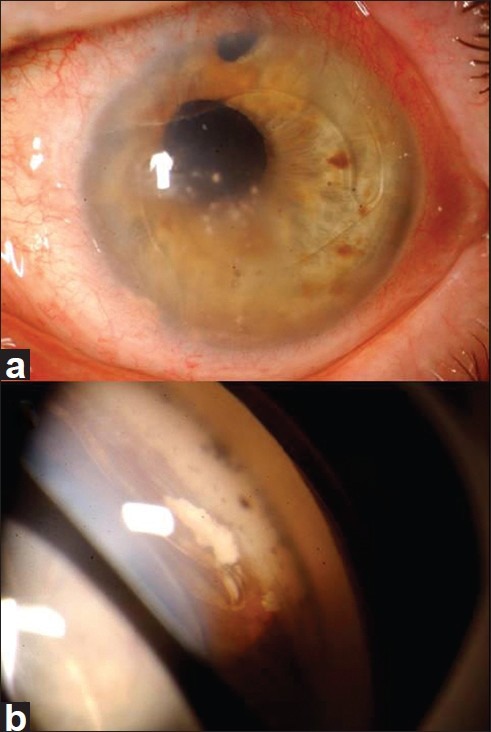

An 80 year-old healthy Caucasian woman without a previous history of systemic cancer was found to have possible iris metastasis versus endophthalmitis. In the 1970s, she had cataract extraction both eyes (OU) without lens implantation. Two years previously, secondary anterior chamber intraocular lens was placed OU. There was no history of postcataract iritis. Visual acuity was 20/400 OD and 20/70 OS. In the affected OS, there was corneal epithelial edema, anterior chamber lens, and an open superior peripheral iridectomy. Fine, linear, bead-like, white lesions within prolapsed vitreous gel in the central anterior chamber was noted and large, bare calcified bodies were seen inferiorly in the angle, unattached to gel. [Figure 2] Vitreous asteroid hyalosis was noted. A diagnosis of anterior segment prolapse of vitreous hyalosis was rendered and observation was advised.

Figure 2.

An 80-year-old asymptomatic woman was referred with a white iris mass suspicious for metastasis or endophthalmitis (a) that proved on examination to be asteroid bodies, some within the central aqueous within gel (a) and others bare in the inferior angle (b)

DISCUSSION

In an autopsy eye study of 10,801 patients, asteroid hyalosis was detected in 1.96% and was significantly correlated with age, male gender, age-related macular degeneration, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and poster vitreous detachment.4 There was no mention of anterior chamber prolapse of asteroid bodies.

In a pathology analysis of 16 eyes (mean age 65 years) with asteroid hyalosis, the vitreous gel was biomicroscopically normal in 16 (81%) and moderately liquefied in 3 (19%).2 With electron microscopy, the asteroid bodies morphologically measured 25-75 um in diameter with porous surface and were densely enmeshed within collagen fibrils, accounting for their linear alignment. By phase contrast microscopy, some bodies showed no cellular reaction while others showed encapsulating multinucleated epithelioid giant cells. By x-ray spectroscopy, calcium phospholipids were confirmed.

In a PubMed search for keywords “asteroid hyalosis” and “asteroid hyalosis anterior chamber,” there was only one convincing case of prolapse of vitreous asteroid hyalosis into the anterior chamber.5 In that 1980 publication, hemorrhage and asteroid hyalosis within prolapsed vitreous gel into the anterior chamber was noted shortly after intracapsular cataract surgery. In our first case, there was no posterior capsular rupture or vitreous gel in the anterior chamber whereas in our second case, there was no capsular remnant and central prolapsed vitreous gel was present. In each case, bare asteroid bodies were present in the anterior chamber angle simulating a tumor, inflammation, or postcataract fibrovascular membrane. We theorized that in case #1, remnants of vitreous gel could have lead to the adhesion of iris to corneal endothelium and in case #2 visible vitreous gel was related to the lack of capsular support.

In summary, vitreous asteroid hyalosis prolapse into the anterior chamber was found in two elderly women several years following cataract surgery. In both cases, the patient was referred for suspected neoplasm in the anterior chamber.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support provided by the Retina Research Foundation of the Retina Society in Cape Town, South Africa (CLS) and the Eye Tumor Research Foundation, Philadelphia, PA (CLS).

The cases used in this study were registered with the institution.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Retina Research Foundation of the Retina Society in Cape Town, South Africa (CLS) and the Eye Tumor Research Foundation, Philadelphia, PA (CLS)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moss SE, Klein R, Klein BE. Asteroid hyalosis in a population: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:70–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00936-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topilow HW, Kenyon KR, Takahashi M. Asteroid hyalosis. Biomicroscopy, ultrastructure, and composition. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:964–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030030972015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergren RL, Brown GC, Duker JS. Prevalence and association of asteroid hyalosis with systemic diseases. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:289–93. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fawzi A, Baotran V, Kriwanek R, Ramkumar HL, Cha C, Carts A, et al. Asteroid hyalosis in an autopsy population. The university of california at los angeles (UCLA) experience. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:486–90. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones WL. Asteroid hyalosis in the anterior chamber. J Am Optom Assoc. 1980;51:66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]