Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the feasibility and potential effectiveness of a 12-week, non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention in patients with generalised osteoarthritis (GOA).

Design

A randomised, concurrent, multiple-baseline single-case design. During the baseline period, the intervention period and the postintervention period, all participants completed several health outcomes twice a week on Visual Analogue Scales.

Setting

Rheumatology outpatient department of a specialised hospital in the Netherlands.

Participants

1 man and four women (aged 51–76 years) diagnosed with GOA.

Primary outcome measures

To assess feasibility, the authors assessed the number of dropouts and adverse events, adherence rates and patients' satisfaction.

Secondary outcome measures

To assess the potential effectiveness, the authors assessed pain and self-efficacy using visual data inspection and randomisation tests.

Results

The intervention was feasible in terms of adverse events (none) and adherence rate but not in terms of participants' satisfaction with the intervention. Visual inspection of the data and randomisation testing demonstrated no effects on pain (p=0.93) or self-efficacy (p=0.85).

Conclusions

The results of the present study indicate that the proposed intervention for patients with GOA was insufficiently feasible and effective. The data obtained through this multiple-baseline study have highlighted several areas in which the therapy programme can be optimised.

Article summary

Article focus

To evaluate the feasibility of a 12-week, non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention in patients with GOA.

To evaluate the potential effectiveness of a 12-week, non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention in patients with GOA.

Key messages

To date, no studies are available that evaluate non-pharmacological multidisciplinary care in individuals with GOA.

The intervention evaluated in the present study appeared both insufficiently feasible and effective for patients with GOA.

Several areas in which the therapy programme could be optimised were highlighted.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A multiple-baseline single-case design is particularly successful in demonstrating immediate effects, whereas we studied changes in health behaviour.

Inherent to the design of the study is lower external validity due to the small number of included participants.

Introduction

A growing body of evidence shows that individuals with established osteoarthritis (OA) with multiple joint involvement—often referred to as generalised osteoarthritis (GOA)—represent a relatively large subgroup of patients.1–4 It has been suggested that these people might be in need of more intensive treatment options than patients with single joint complaints.1 5 To the best of our knowledge, however, there are no studies that evaluate non-pharmacological multidisciplinary care in individuals with GOA,5 warranting the development and evaluation of such a treatment programme. Therefore, we conceptualised a non-pharmacological multidisciplinary treatment programme following a previously described systematic procedure.6 The intervention was based on recommendations for the management of hip and knee OA7–9 and was tailored to the needs of patients with multiple joint involvement.1 Due to the complex nature of multiple joint involvement in OA1–4 and the fact that guidelines for hip and knee OA recommend multiple non-pharmacological treatment modalities, an intervention was developed by a multidisciplinary team.8

Before evaluating such an intervention in a randomised clinical trial, a pilot study is recommended10 since the evaluations are often undermined by problems of acceptability, compliance, delivery of the intervention, recruitment and retention, and smaller-than-expected effect sizes.11 A useful study design for pilot interventions is the multiple-baseline single-case design, as it allows researchers to test the feasibility of the intervention and to make an assessment of its potential effectiveness with a low number of participants.12 In a multiple-baseline design, the intervention is introduced to subjects after randomly assigned baseline periods of different lengths, and an effect is demonstrated if the measured outcome only changes after the intervention has been introduced.13

The primary aim of our study was to evaluate the feasibility of a non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention in patients with GOA. Our secondary aim was to assess the potential effectiveness of this intervention on pain and self-efficacy.

Methods

Participants

Men and women, aged 40 years or older and referred to the multidisciplinary intervention, were eligible to participate in the present study if they had been diagnosed with GOA, that is, experiencing complaints in three or more joint groups, having at least two objective signs that indicate OA in at least two joints and having limitations in daily functioning (Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index Score14 >0.5).15 Individuals were excluded from participation in the intervention if: (1) they were awaiting joint replacement surgery, (2) they had already participated unsuccessfully in a self-management programme for their GOA complaints, (3) their therapists suspected that they were having high levels of distress, (4) they did not master the Dutch language or (5) they were illiterate. Recruitment and treatment of patients took place at the rheumatology outpatient department at the Maartenskliniek Woerden (the Netherlands).

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Centre Nijmegen (protocol number 2009/173) and did not fall within the remit of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Design

A randomised, concurrent, multiple-baseline single-case design was applied.13 Participants completed repeated measurements during a baseline phase (phase A), an intervention period (phase B, 12 weeks) and a postintervention period (phase A′). Phase A acted as a control and was therefore compared with phases B and A′. By applying multiple baselines of varying length, observed effects of the treatment can be distinguished from effects due to chance,12 16 17 thus increasing internal validity. The total duration of phases A and A′ was set at 7 weeks for each participant, and consequently, participants with a longer phase A had a shorter phase A′. Participants were randomly assigned to a baseline and postintervention period of 2 and 5 weeks, 2.5 and 4.5 weeks, 3 and 4 weeks, …, or 5 and 2 weeks, respectively, using the Wampold–Worsham method18 to increase statistical power. During the total study period of 19 weeks, the participants completed diary measures twice a week, resulting in a total of 38 measurement points (14 during phases A and A′ and 24 during phase B). Each diary measure comprised 14 Visual Analogue Scales (VAS).

Measurements

Feasibility of the intervention

To evaluate the feasibility of the intervention, we assessed (1) the number of, and reasons for, dropouts during the intervention, (2) the adherence to the intervention (number of no shows), (3) the occurrence of adverse events related to the intervention, (4) the participants' satisfaction with the intervention (straightforward question ranging from 0 (totally dissatisfied) to 10 (totally satisfied)) and (5) the participants' satisfaction with the assessment procedure (straightforward yes/no questions).

Diary measures

Diary measures comprised 14 VAS (scoring range from 0 to 10). Pain and fatigue were measured by single straightforward questions. Furthermore, 12 items derived from validated questionnaires were scored on a VAS. Kinesiophobia was measured with four VAS.19 Self-efficacy was assessed using two questions from the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale.20 Acceptance of the disease was measured with two questions from the subscale Acceptance of the Illness Cognition Questionnaire,21 and illness perceptions were evaluated by two questions from the Illness Perception Questionnaire.22 To assess the specific complaints of each participant, we used the Patient-Specific Complaints Questionnaire.23 The most important complaint was assessed through the diary measure. For all scales, a higher score represented unfavourable outcomes. Pain and self-efficacy were our main secondary outcome measures.

Preintervention and postintervention measures

At baseline, we collected data on age, sex, level of education (low (no or primary education), medium (secondary school and/or preparatory middle-level vocational education), high (university of applied sciences and/or university)) and duration of symptoms. Prior to the start of the programme, we also assessed participant's expectations about its effectiveness on a scale from 0 to 10 (0 representing ‘No expectations whatsoever’). Preintervention and postintervention measures consisted of a set of validated questionnaires. We measured fatigue with the ‘Subjective Fatigue’ subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength,24 on which higher scores represent greater fatigue. Self-efficacy was evaluated with the General Self-Efficacy Scale,25 where higher scores represent higher levels of self-efficacy. Acceptance and helplessness were measured using the Illness Cognitions Questionnaire,26 where higher scores reflect higher levels of agreement with that generic illness cognition. As no specific questionnaires are available to assess the self-reported functional status of individuals with GOA, we used generic questionnaires for both the lower and upper extremities, namely the Lower Extremity Functional Scale27 and the Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand, respectively.28 Higher scores on the Lower Extremity Functional Scale and Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand represent lower and greater disability, respectively.

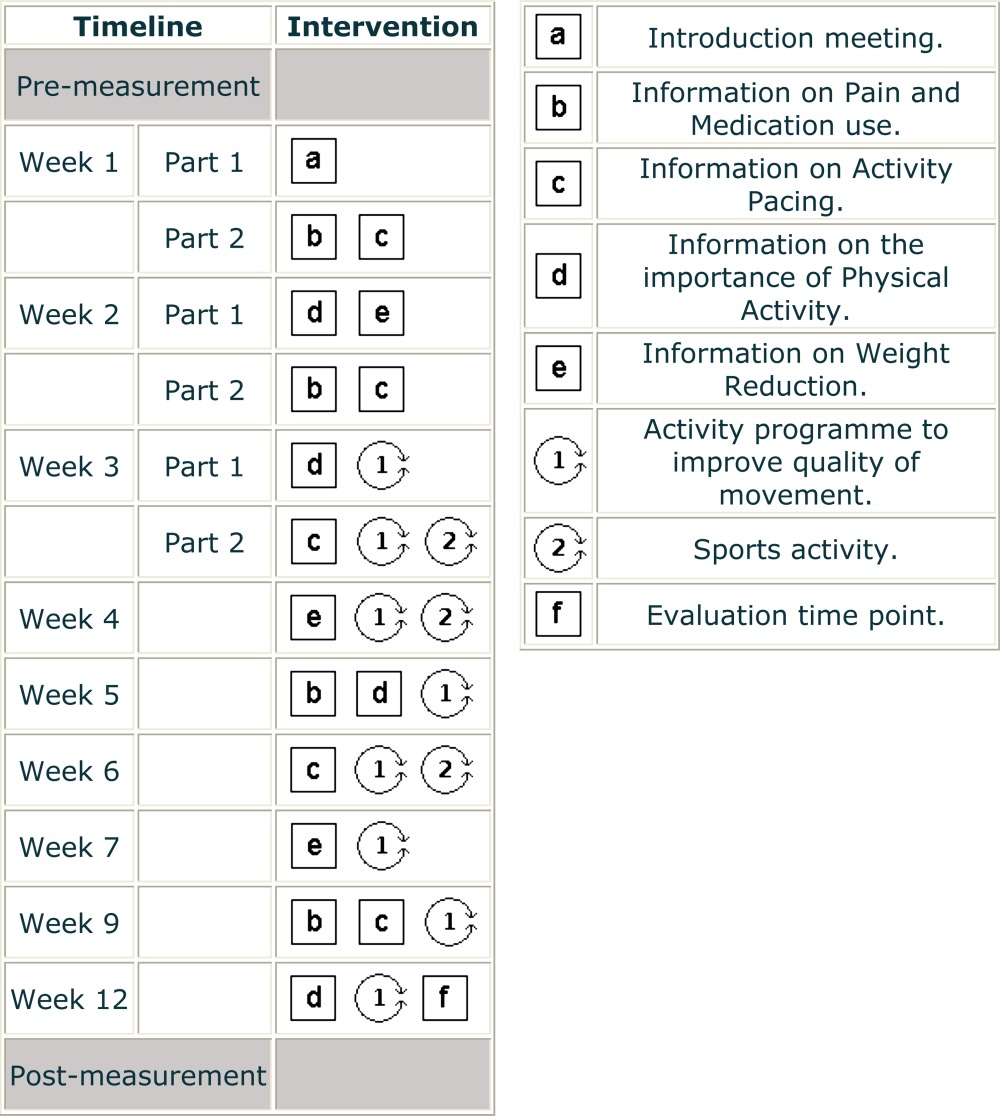

Intervention

The group-based intervention (eight persons per group) lasted 12 weeks, comprised 10 sessions of approximately 1.5 h per session, and was provided by an occupational therapist and physical therapist. To ensure group learning, the treatment programme was decided to be delivered in a group setting. The intervention aimed to increase the participants' knowledge of the disease, to optimise the participants' current lifestyle and to enhance the participants' self-efficacy in controlling the disease.

To do so, patients received information on activity pacing, medication use, physical activity and weight reduction. Consequently, based on the received information, participants set personal goals regarding all these health areas. By setting these personal goals, participants transferred the health information into practical and personally relevant therapy goals. Goal setting and monitoring were done according to the 5-As model of behaviour change counselling,29 a generally accepted method to enhance self-efficacy in healthcare settings. During each session, after the initial information session, the individual goals were monitored and discussed. To allow for positive feedback regarding the personal goals, all goals had to be achievable in brief amounts of time. Some examples of personal therapy goals were: (1) for the next 3 days, while at work, plan and perform 15 min of physical activity spread over three different time points (component Physical Activity); (2) for the next week, while cleaning the house, alternate (maximum of 10 min) between vacuum cleaning, other household chores and rest moments (component Activity Pacing); (3) for the next week, use your pain medication (two tablets of paracetamol (500 mg)) four times a day and monitor your pain during this period (component Medication Use) and (4) for the next week, eat at least 3 days two slices of whole wheat bread as breakfast (component Weight Reduction).

In addition, daily activities (such as walking, sitting, standing, stair climbing and getting in and out of bed) were included in the therapeutic activity programme. Participants received information and practised how to perform these daily activities without overexerting the joints and muscles. Participants were instructed and encouraged to implement these techniques and methods of performing the activities in their daily practice.

Finally, participants were familiarised with different kinds of sports, tailored to the participants' complaints to prevent overexertion (ie, tai chi, brisk walking and therapeutic fitness). An overview of the intervention is depicted in box 1. Participants were advised to implement these recommendations in their home situation.

Box 1. Pat-plot of the multidisciplinary intervention.

|

Data analysis

All data were entered into the data entry program Epidata.30 Ten per cent of the data were entered twice to establish the quality of data entry. Missing data were described.

Diary data were analysed using the 2-SD band method17 (visual inspection) and randomisation tests.31 The 2-SD band was calculated from the baseline data and graphed from the baseline phase through the intervention phase. If two or more successive data points in the intervention or postintervention phase fell outside the bandwidth of 2 SDs, the result was considered significant.17 As serial dependence—the extent to which scores at one point in a series are predictive of scores at another point in the same data set—can bias the visual inspection,17 we checked our data in each phase for serial dependence using the lag-1 method.12 If data were found to be significantly correlated, we transformed the data using a moving-average transformation, in which the preceding and succeeding measurements were taken into account.12 16 In addition, randomisation tests for multiple-baseline single-case designs were carried out. We expected phases B and A′ to be superior to phase A in terms of our health outcome assessment. Therefore, we tested the null hypothesis—that there would be no differential effect for any of the measurement times—using a randomisation test of the differences in the means between the preintervention phase and the intervention or postintervention phase.17 A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the pre-measurements and post-measurements, we considered change scores of 20% on validated questionnaires as clinically relevant.32 We used Stata/IC 10.1 for Windows for the descriptive and visual analysis of the data and R version 2.14.1 for the randomisation tests.31

Results

Nine people were screened to participate in the study; two patients were excluded as they did not report functional disabilities (Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index Score <0.5) and two patients who were eligible were unable to attend the programme. Eventually, five participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study. One patient dropped out of the study within 2 weeks after the start of the study, reporting that filling out the questionnaires was too demanding for her on an emotional level. However, she did continue with the multidisciplinary intervention. The four remaining participants completed all 38 diary measures, resulting in 2128 completed items. Six items (0.3%) were missing. Data entry errors were negligible (<0.1%). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Participant | Sex | Age (years) | Education | No. of painful joint groups (0–11) | Baseline assignment (measurements) |

| 1 | F | 76 | Low | 8 | 4 |

| 2 | F | 68 | Medium | 3 | 5 |

| 3 | M | 59 | Low | 11 | 7 |

| 4 | F | 56 | High | 5 | 6 |

| 5* | F | 51 | High | – | 6 |

Dropped out.

F, female; M, male.

Feasibility of the intervention

Prior to the intervention, participants' expectations regarding the effectiveness of the intervention ranged from 5 to 7 (median=7). Participant 3 missed three of the 10 sessions; participants 2 and 4 missed one session. Participant 1 reported an increase in pain levels, which she ascribed to the intervention. Satisfaction with the intervention was assigned a score of 8 points out of 10 by participants 1, 2 and 4, and 7 points out of 10 by participant 3. Perceived therapy effects were assigned a score of 7, 3, 5, and 7 out of 10 by participants 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. All participants believed that the questionnaires used in this study properly evaluated their most important issues. The remarks most frequently made by participants regarding the intervention were: (1) there were too many sessions and these were too short/brief, (2) too much verbal information, (3) too much time between two sessions, (4) too little information on acceptance of the disease and (5) too little individualisation in the exercise sessions, and in setting and monitoring therapy goals.

Diary measures

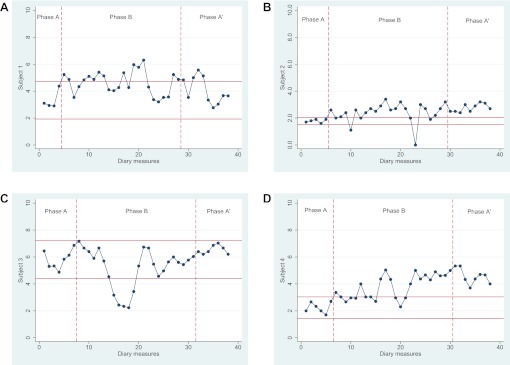

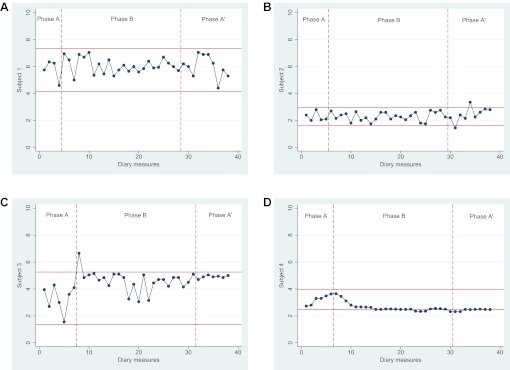

Our primary effectiveness outcome measures were pain and self-efficacy. In the pain data, the intervention phase of participant 3 showed serial dependence and that of participants 1 and 4 showed large fluctuations. Thus, we transformed these data prior to completion of visual data analysis. The 2-SD band method showed that participants 1, 2 and 4 each experienced significant deterioration in their pain scores between baseline, intervention and postintervention phases. Participant 3 demonstrated significant improvement during the intervention phase (figure 1), though this did not persist during the postintervention phase. For all four participants, randomisation tests demonstrated no significant changes in pain between the preintervention phase and the intervention/postintervention phase (p=0.93). Serial dependence was found in the self-efficacy data of participant 4, and these data were transformed prior to the analyses. The 2-SD band method demonstrated that participant 4 experienced significantly higher levels of self-efficacy in both the intervention and postintervention phase compared with the baseline phase. No differences were found for participants 1, 2 and 3 (figure 2). Randomisation testing demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the phase prior to the intervention and the phases during and after the intervention (p=0.85). Outcomes of the randomisation tests for our secondary effectiveness outcome measures were: fatigue (p=0.79), patient-specific complaints (p=0.64), kinesiophobia (p=0.02), illness cognitions (p=0.69) and illness perception (p=0.60).

Figure 1.

Diary measures for pain with 2-SD horizontal band graph for baseline (phase A), intervention (phase B) and postintervention (phase A′) phases. Scores on the pain Visual Analogue Scale range from 0 to 10; higher scores indicate higher levels of pain.

Figure 2.

Diary measures for self-efficacy with 2-SD horizontal band graph for baseline (phase A), intervention (phase B) and postintervention (phase A′) phases. Scores on the pain Visual Analogue Scale range from 0 to 10; higher scores indicating lower levels of self-efficacy.

Pre-measurements and post-measurements

Table 2 depicts the clinically relevant changes from baseline for each of the four participants. None of the participants reported improvement in self-efficacy. Participant 1 experienced clinically relevant deterioration in self-efficacy, upper body function and kinesiophobia. Participant 4 reported improvements in fatigue levels, upper body function, kinesiophobia and acceptance. Both participants 2 and 3 remained stable.

Table 2.

Clinically relevant differences between baseline and postintervention measurements

| Fatigue |

Self-efficacy |

Function |

Kinesiophobia |

Illness cognitions |

||||||||||

| T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | Upper |

Lower |

T0 | T1 | Help |

Accept |

|||||

| T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | |||||||

| pt1 | 42 | 39 | 35 | 27 | 35 | 50 | 44 | 47 | 43 | 50 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 |

| pt2 | 9 | 9 | 35 | 37 | 18 | 13 | 69 | 68 | 28 | 31 | 8 | 9 | 23 | 24 |

| pt3 | 56 | 33 | 35 | 30 | 31 | 43 | 38 | 41 | 57 | 53 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 19 |

| pt4 | 34 | 27 | 29 | 31 | 44 | 32 | 46 | 48 | 48 | 34 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 14 |

Bold values represent 20% improvement, and italics values represent 20% deterioration.

Accept, subscale acceptance; Help, subscale helplessness; Lower, lower extremity functioning; pt, participant; T0, baseline measurement; T1, postintervention measurement; Upper, upper extremity functioning.

Discussion

Our data suggest that the tailored, 12-week, non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention for patients with GOA was feasible in terms of adverse events, number of dropouts and participation rate. On the other hand, the participants raised several critical points concerning the structure, content and perceived benefits of the intervention. The latter was confirmed by visual inspection of the data and randomisation testing, as the intervention did not demonstrate clear-cut effects on health-related factors. Therefore, we believe that the content and structure of the current intervention does not warrant further evaluation in a randomised clinical trial.

In view of the participants' remarks, we believe that the intervention should be more individually tailored. One of the remarks was that the therapeutic movement programme was not sufficiently individualised to address the participants' health problems. In a future non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention, it might be of value to incorporate the results of the Patient-Specific Complaints instrument23 in the therapeutic activity programme. Moreover, it was suggested that setting and achieving goals should be monitored more closely. To do so, participants should draw up action plans by completing goal setting forms to formulate short-term goals, while being aware of potential limiting factors. In this way, personal goals could be monitored, discussed and adjusted, which in turn might increase the involvement and self-efficacy of the participants.17 Finally, participants had relatively low treatment expectations regarding the intervention (highest score was 7 out of 10), implying that participants might have lacked an active role prior to the start of intervention. Motivation is considered one of the most important factors for the success of a self-management programme.33 34 Therefore, to increase the effectiveness of a non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention in patients with GOA, attention should be paid to participants' motivation prior to inclusion. Furthermore, therapists could be trained in motivating and goal setting techniques, for example, motivational interviewing.

Several limitations should be taken into account when interpreting our data. First, we used a concurrent multiple-baseline single-case design to evaluate the intervention's potential effectiveness. This design is particularly successful in demonstrating immediate effects.35 Since our intervention aimed to improve self-management in individuals with OA, which is often considered challenging and time-consuming,9 our choice of study design might not be optimal, given the short evaluation period and the considerable length of the treatment programme. A second limitation was that all participants were in the same therapy group, possibly resulting in a negative group effect compromising any therapy effects. On the other hand, the traditional approach to multiple-baseline studies is for all participants to undergo treatment simultaneously.13 This strategy is recommended as it improves internal validity, particularly in terms of history effects.36 A third limitation, inherent to the design of the study, is that the study has lower external validity than randomised clinical trials, for which participants are usually selected to form a generalisable sample.37 A fourth limitation of this study was its inability to test the feasibility of study logistics for a randomised clinical trial (eg, recruitment rate, dropout rate and issues concerning randomisation).38 A final limitation was that we selected patients based on their medical diagnosis and functional status rather than on their scores on our main secondary outcomes (ie, pain and/or self-efficacy). Future studies should include clinically relevant thresholds for their outcome measures in the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

As far as we know, we are the first to study a multidisciplinary intervention to improve self-management in people with GOA. Due to differences in study populations, our results cannot be compared with those of another study into the effect of a non-pharmacological multidisciplinary intervention in patients with GOA after major joint replacement surgery.39 It is remarkable that so little research is available given the relatively high prevalence of individuals with established OA with multiple joint involvement and its association with compromised health status.1 2

Some consider single-case experimental designs as viable alternatives to large-scale randomised clinical trials,40 41 whereas others state the opposite.37 42 While using this design, we faced several (practical) constraints that potential users should be aware of. As yet, there is a plethora of analytical techniques for single-case data,31 with little or no consensus on the optimal way to analyse the data. In our study, we demonstrated a significant effect of our intervention on kinesiophobia using a randomisation test, whereas visual inspection showed only clear effects in one participant. Another practical consideration is that the design requires a substantial contribution from the participants. In the present study, one of the participants dropped out as she experienced additional psychological burden due to recurring questionnaires. It remains to be elucidated whether frequent assessment of health status as in the current study negatively, or perhaps positively, influences health outcomes. In our opinion, the multiple-baseline single-case study is a useful and valid alternative to the randomised pilot study, as it gives insight into the feasibility of the intervention and allows to evaluate the intervention's potential effectiveness, allowing one to tailor the content and context of the intervention prior to conducting a randomised clinical trial. However, single-case studies should only be considered an alternative to a full-sized randomised clinical trial in rare diseases or in situations where a randomised clinical trial is unfeasible or unethical because of the designs' limitations, including low external validity of the findings and the inability to correct for confounders (such as medication use, age, disease duration).

An interesting finding was the marked variability in VAS scores within participants on specific outcomes. For example, three participants reported fluctuations in pain scores of more than 4 points within a period of half a week (ie, between two measurement points). Fluctuations in pain between two measurement points ranged from 0 to 7 points, frequently exceeding the thresholds for clinically relevant differences.43 Such fluctuations indicate that pain in OA is far less stable than often believed and should perhaps be assessed far more frequently. As such variations are also likely to occur in randomised clinical trials, researchers should consider assessing postintervention health outcomes at repeated time points. These outcomes could then be averaged to obtain a more stable postintervention point estimate.

In conclusion, health providers and researchers should be aware of the lack of studies on the effectiveness of non-pharmacological and/or multidisciplinary interventions for patients with GOA. In our study, although we systematically conceptualised our intervention according to the latest evidence7–9 and in collaboration with several healthcare providers, both feasibility and effectiveness of the care programme are doubtful. Therefore, the therapy programme as described in this paper does not warrant evaluation in a large randomised clinical trial. Since the data obtained in this multiple-baseline study have highlighted several ways in which the therapy programme could be optimised/improved, these changes should be implemented prior to conducting an RCT to further examine the interventions' effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Hoogeboom TJ, Kwakkenbos L, Rietveld L, et al. Feasibility and potential effectiveness of a non-pharmacological multidisciplinary care programme for persons with generalised osteoarthritis: a randomised, multiple-baseline single-case study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001161. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001161

Contributors: Substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study: TJH, LK, LR, AAdB, RAdB and CHMvdE. Substantial contribution to the acquisition of the data: TJH and LR. Substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data: TJH, LR, LK, AAdB and CHMvdE. Provided intellectual content while drafting the article: TJH, LR, LK, AAdB and CHMvdE. Approved the final version to be published: TJH, LR, LK, AAdB and CHMvdE.

Funding: The study was financed by the Sint Maartenskliniek Nijmegen and Woerden, the Netherlands.

Competing interests: All authors declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Patient consent: All patients provided written informed consent. Our article does not contain personal medical information about an identifiable living individual.

Ethics approval: The ethics approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Centre Nijmegen.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hoogeboom TJ, den Broeder AA, Swierstra BA, et al. Joint-pain comorbidity, health status, and medication use in hip and knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:54–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suri P, Morgenroth DC, Kwoh CK, et al. Low back pain and other musculoskeletal pain comorbidities in individuals with symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1715–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forestier R, Francon A, Briole V, et al. Prevalence of generalized osteoarthritis in a population with knee osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2011;78:275–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Günther KP, Stürmer T, Sauerland S, et al. Prevalence of generalised osteoarthritis in patients with advanced hip and knee osteoarthritis: the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57:717–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conaghan P, Birrell F, Burke M, et al. Osteoarthritis: National Clinical Guideline for Care and Management in Adults. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stukstette M, Hoogeboom T, de Ruiter R, et al. A multidisciplinary and multidimensional intervention for patients with hand osteoarthritis. Clin Rehabil 2012;26:99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:981–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:137–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:476–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Feder GS, et al. Lessons for cluster randomized trials in the twenty-first century: a systematic review of trials in primary care. Clin Trials 2004;1:80–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backman CL, Harris SR, Chisholm JA, et al. Single-subject research in rehabilitation: a review of studies using AB, withdrawal, multiple baseline, and alternating treatments designs. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:1145–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christ T. Experimental control and threats to internal validity of concurrent and nonconcurrent multiple baseline designs. Psychology in the School 2007;44:451–9 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, et al. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:137–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoogeboom TJ, Stukstette MJ, de Bie RA, et al. Non-pharmacological care for patients with generalized osteoarthritis: design of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nourbakhsh MR, Ottenbacher KJ. The statistical analysis of single-subject data: a comparative examination. Phys Ther 1994;74:768–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtgrefe K, McCloy C, Rome L. Changes associated with a quota-based approach on a walking program for individuals with fibromyalgia. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2007;37:717–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferron J, Sentovich C. Statistical power of randomization tests used with multiple-baseline designs. JXE 2002;70:165–78 [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Jong JR, Vlaeyen JW, de Gelder JM, et al. Pain-related fear, perceived harmfulness of activities, and functional limitations in complex regional pain syndrome type I. J Pain 2011;12:1209–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorig K, Holman H. Arthritis self-efficacy scales measure self-efficacy. Arthritis Care Res 1998;11:155–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Lankveld W, et al. Beyond unfavorable thinking: the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. J Consult Clin Psychol 2001;69:1026–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bijsterbosch J, Scharloo M, Visser AW, et al. Illness perceptions in patients with osteoarthritis: change over time and association with disability. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1054–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Köke AJ, et al. A patient-specific approach for measuring functional status in low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999;22:144–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beurskens AJ, Bültmann U, Kant I, et al. Fatigue among working people: validity of a questionnaire measure. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:353–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol 2005;139:439–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maas M, Taal E, van der Linden S, et al. A review of instruments to assess illness representations in patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:305–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoogeboom TJ, de Bie RA, den Broeder AA, et al. The Dutch Lower Extremity Functional Scale was highly reliable, valid and responsive in individuals with hip/knee osteoarthritis: a validation study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 2012;13:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, et al. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther 2001;14:128–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glasgow RE, Emont S, Miller DC. Assessing delivery of the five ‘As’ for patient-centered counseling. Health Promot Int 2006;21:245–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauritsen JM, Bruus M. EpiData (version). A comprehensive tool for validated entry and documentation of data. The EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark, 2003–2005 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bulté I, Onghena P. Randomization tests for multiple-baseline designs: an extension of the SCRT-R package. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:477–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Escobar A, Gonzalez M, Quintana JM, et al. Patient acceptable symptom state and OMERACT-OARSI set of responder criteria in joint replacement. Identification of cut-off values. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012;20:87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeWalt DA, Davis TC, Wallace AS, et al. Goal setting in diabetes self-management: taking the baby steps to success. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:218–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, et al. Exercise motivation, eating, and body image variables as predictors of weight control. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:179–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neuman SB. Single-subject experimental design. In: Duke NK, Mallette MH, eds. Literacy Research Methodologies. 2nd edn New York: The Guilford Press, 2011:383 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr JE. Recommendations for reporting multiple-baseline designs across participants. Behav Intervent 2005;20:219–24 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newcombe RG. Should the single subject design be regarded as a valid alternative to the randomised controlled trial? Postgrad Med J 2005;81:546–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bulthuis Y, Drossaers-Bakker KW, Taal E, et al. Arthritis patients show long-term benefits from 3 weeks intensive exercise training directly following hospital discharge. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1712–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizvi SL, Nock MK. Single-case experimental designs for the evaluation of treatments for self-injurious and suicidal behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2008;38:498–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janosky JE. Use of the single subject design for practice based primary care research. Postgrad Med J 2005;81:549–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guyatt GH, Keller JL, Jaeschke R, et al. The n-of-1 randomized controlled trial: clinical usefulness. Our three-year experience. Ann Intern Med 1990;112:293–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JS, Hobden E, Stiell IG, et al. Clinically important change in the visual analog scale after adequate pain control. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:1128–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.