Abstract

Background:

Macular amyloidosis (MA) is the most subtle form of cutaneous amyloidosis, characterized by brownish macules in a rippled pattern, distributed predominantly over the trunk and extremities. MA has a high incidence in Asia, Middle East, and South America. Its etiology has yet to be fully elucidated though various risk factors such as sex, race, genetic predisposition, exposure to sunlight, atopy and friction and even auto-immunity have been implicated.

Aim:

This study attempts to evaluate the epidemiology and risk factors in the etiology of MA.

Materials and: Methods:

Clinical history and risk factors of 50 patients with a clinical diagnosis of MA were evaluated. Skin biopsies of 26 randomly selected patients were studied for the deposition of amyloid.

Results:

We observed a characteristic female preponderance (88%) with a female to male ratio of 7.3:1, with a mean age of onset of MA being earlier in females. Upper back was involved in 80% of patients and sun-exposed sites were involved in 64% cases. Incidence of MA was high in patients with skin phototype III. Role of friction was inconclusive

Conclusion:

Lack of clear-cut etiological factors makes it difficult to suggest a reasonable therapeutic modality. Histopathology is not specific and amyloid deposits can be demonstrated only in a small number of patients. For want of the requisite information on the natural course and definitive etiology, the disease MA remains an enigma and a source of concern for the suffering patients.

Keywords: Epidemiology, macular amyloidosis, risk factors

Introduction

Macular amyloidosis (MA) represents a common variant of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA). Macular form of cutaneous amyloidosis was first described by Palitz and Peck in 1952.[1] MA has a characteristic female preponderance[2–7] with the age of onset ranging between 21 and 50 years.[7] Clinically, MA presents as poorly delineated hyperpigmented patches of grayish-brown macules with a rippled pattern,[8] associated with deposition of amyloid material in the papillary dermis.[9] The sites most commonly involved are the interscapular area,[10] extremities (shins and forearms),[11,12] although involvement of the clavicles, breast, face, neck, and axilla[2] have also been reported. Various risk factors such as, race,[2,8] female gender,[3,6,10] genetic predisposition,[13] sun exposure,[12] atopy[14] and friction[12,15–17] have been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of MA. On the basis of a patient of PLCA having sarcoidosis and IgA nephropathy and increasing number of reports suggesting immune mediated factors, the possibility of autoimmune basis in a group of patients with extensive disease was also proposed.[18] Yet, its etiology still remains an enigma.

It is the most subtle form of cutaneous amyloidosis and tends to persist unchanged for many years. The natural course of the disease is not well described. Though the exact incidence of MA is not known, it is by no means an uncommon disease. In our study comprising 50 patients from Northern India, we studied the possible etiological and risk factors of MA.

Materials and Methods

Fifty patients with a clinical diagnosis of MA attending the out-patient clinic of a tertiary care dermatology center were enrolled in the study. The study design was approved by the Institute's Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to enrollment. Complete history and physical examination to exclude any associated systemic disorder or drug usage leading to cutaneous pigmentation was obtained. The age of onset, gender, skin type, duration, sites of involvement, pruritus, history of friction, sun exposure, personal and family history of MA and/or atopy were recorded. Punch biopsies of 4-mm diameter from 26 randomly selected patients were fixed in 10% formalin and processed as required for light microscopy. All the slides were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Congo red, to study the location of amyloid and its extension to adjoining vessels and appendages under light microscope and polarized light.

Results

The prevalence of MA in our out-patient clinic was observed to be 0.03% of all dermatological patients with a characteristic female preponderance. Forty-four of the 50 patients were females (88%), with a female to male ratio of 7.3:1. The age of onset of MA for all patients ranged between 16 and 59 years. The mean age of onset was 34.6±10.5 years, being earlier in females (34.2±10.9 years) compared to males (38±6.78 years). Half the patients (50%) experienced pruritus of varying degrees, and only three patients experienced severe pruritus. Only 16 (32%) patients gave a history of use of nylon scrubs and towels. In our study, there was a wide variation in the duration of the disease ranging from 1 month to 12 years. More than one site was involved in 30 (60%) patients. The most common sites of involvement were the upper back (interscapular area) seen in 40 (80%) patients [Figure 1]. The other sites of involvement in decreasing order of frequency were extensor aspect of arm(s) in 30 (60%) and extensor aspect of legs in 17 (34%) patients [Figure 2]. Bony prominences such as clavicular and scapular regions were involved in three patients each, with rare sites like the buttocks being involved in one patient. Clinically, the lesions in all of our patients presented as hyperpigmented macules, predominantly in a rippled pattern. Coalescence of the macules was observed in 20 (40%) patients. A biphasic pattern comprising both macular and lichen amyloidosis was seen in three (6%) patients. Family history of MA was present in 10 (20%) patients. More than half of our patients, 32 (64%) had involvement of sun-exposed sites, comprising upper back, extensor aspect of arms and legs, whereas 13 (26%) patients had lesions on both sun-protected and sun-exposed sites and only five (10%) patients had involvement of sun-protected sites.

Figure 1.

Macular amyloidosis on the upper back

Figure 2.

Macular amyloidosis on the extensor aspect of the arm

Thirty-nine (78%) patients in our study had skin phototype III; the rest were of skin phototype IV. The average age at onset of MA in patients with skin phototype III was 30.8 years and was lower than that observed in patients with skin phototype IV (34.4 years). Various systemic and cutaneous diseases in association with MA in our patients were chronic urticaria, diabetes mellitus, acne vulgaris, generalized xeroderma, hypothyroidism, hypertension and idiopathic hirsutism.

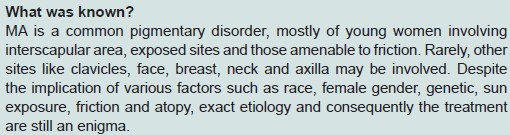

Histopathological findings from the 26 biopsies undertaken and studied are summarized. Epidermis was essentially normal in most of the sections. Mild to moderate thinning of the epidermis was seen in seven (27%) patients [Figure 3]. There was mild hyperkeratosis of the epidermis in three (11.5%) specimens which showed moderate degree of acanthosis with broadening and elongation of the rete ridges. These changes did not always correlate with the deposition of amyloid and extended well beyond the areas of amyloid deposits. Necrotic keratinocytes were seen in the suprabasal region and in the basal layers of the epidermis in five (19%) sections. Occasionally, more number of necrotic keratinocytes were found overlying the subepidermal amyloid deposits. Focal disruption of the basal cell layer with pigment incontinence and melanophages in the papillary dermis were seen in four (15%) biopsy specimens. Predominant perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate was seen in majority of sections (23 out of 26 (88%).

Figure 3.

Microphotograph showing mild epidermal thinning and congophillic material in the papillary dermis (Congo red ×280)

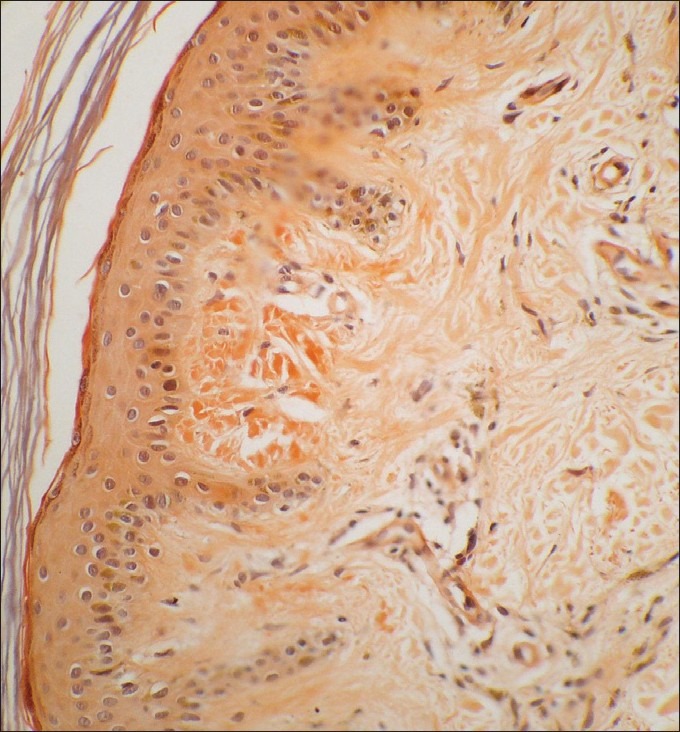

In the sections stained with H&E and Congo red, amyloid deposits could be visualized in three and four specimens respectively on light microscopy [Figure 3]. On viewing, the Congo red-stained sections under polarized light, amyloid deposits with apple green birefringence were detected in seven biopsy specimens [Figure 4]. The amyloid was localized to the subepidermal zone and not scattered or localized around blood vessels or appendages.

Figure 4.

Microphotograph showing apple birefringence with congophillic material (polarized light ×540)

Discussion

Amyloidosis is an extra-cellular deposition of the fibrous protein either involving multiple organ systems (systemic amyloidosis) or restricted to a single-tissue site (localized amyloidosis).[8,19] The various localized forms of amyloidosis confined to the skin are lichen amyloidosis, MA and the rare nodular or tumefactive amyloidosis.[8,19] Not infrequently, features of lichen and MA may coexist and are termed as biphasic amyloidosis.[8,20] In primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA), amyloid deposits are seen in previously normal skin, with no evidence of deposits in internal organs.[19]

MA clinically presents as small (2-4 mm) brownish macules with a characteristic reticulated or rippled pattern, which may coalesce to form poorly circumscribed hyperpigmented areas.[10] The common sites of occurrence are upper back[3,10] (interscapular areas) and extremities (shins and forearms).[3,11] Less commonly, the clavicles, breast, face, neck, axilla[2] and ribs are involved.[19–22] MA has a high incidence in Asia, Middle East and South America, but is rarely seen in European and North American countries.[2,8] Although most cases of PLCA are sporadic, 10% of cases have been reported to be familial.[3,23] Female preponderance has been consistently reported in the literature,[3,6,14] except for a study by Black et al. which reported more males to be affected.[24] We observed a similar female prevalence with a female to male ratio of 7.3:1. It has been suggested that female preponderance maybe due to medical attention sought earlier by women for the cosmetically disturbing pigmentation.[3,10,24,25] The role of female sex hormones has also been hypothesized although conclusive studies are lacking.[7]

The patients’ ages ranged between 16 and 59 years similar to the previous reports,[7,24,26] with a mean age of onset of 34.6±10.5 years. The mean age of onset of MA was lower in women, compared to men, which was contrary to a report by Rasi et al.,[7] where a higher mean age on onset for females was reported. In our study, there was a wide variation in the duration of the disease at the time of presentation (1 month-12 years), and about half of the patients presented within 2 years of appearance of the lesions. This may be attributed to the nonavailability of a satisfactory treatment. Apart from the considerable cosmetic disability, patients occasionally complain of troublesome pruritus. Twenty-two patients (44%) in our study complained of itching which was minimal to moderate in intensity with only three patients complaining of severe itching. Although itching is a frequent symptom in PLCA, it is not a universal finding and has been reported to be absent in 20% of patients. In a study by al-Ratrout and Satti,[3] six of the 10 patients complained of mild to moderate pruritus which increased in intensity in two patients during conditions of high humidity. We did not observe such a pattern in our study.[10,26–28]

Mechanical trauma such as that induced by nylon fibers and bristles has been considered in the etiology of MA and has been reported under various names, such as friction amyloidosis, towel melanosis and nylon clothes friction dermatitis.[17,27,29] Only 16 (32%) of our patients gave a history of using nylon scrubs or towels, but the perceived excessive friction did not correlate with the sites having pigmentary lesions. Similar observations were made in studies by Rasi et al.[7] and Eswaramoorthy et al.[6] As in previous studies, we could not find any correlation between the use of cosmetics, shampoos, soaps and creams and MA.[6] Personal history of atopy was present in seven of our patients, of whom three had family history of atopy. However, the relationship if any between history of atopy and MA has not been either confirmed or explained.[24] Frequent involvement of back, extensor aspects of upper limbs and clavicular areas compared to sun-protected sites like lower back, legs, thighs, buttocks and breast would point to exposure of ultraviolet (UV) rays as an etiological factor in MA. Moreover, sunny weather contributing to increased pigmentation in PLCA has previously been reported.[17] Sun-protected sites were involved in only 10% of our patients with sun-exposed sites being involved in a higher number of patients (64%). Upper back was involved in 40 patients. Hence, sunlight could be incriminated as a risk factor in the causation of MA in our patients. Eswaramoorthy et al.[6] and Rasi et al.,[7] however, did not find any correlation between sun exposure and MA in their studies. Epidemiologically, PLCA is prevalent in populations which generally have a high skin phototype (IV and V).[3,17] This might explain its rarity in western countries. In our study, majority of patients had skin phototype III (78%), which is common phototype in North India and rest had phototype IV.

MA classically presents in a rippled pattern or as reticulate pigmentation.[3,10] Unusual presentations of MA, such as nevoid like hyperpigmentation, widespread diffuse pigmentation, poikiloderma like, incontinentia pigment like and linear MA have frequently been reported in the literature.[22,30–33] A rippled pattern of pigmentation was present in all of our patients without any special pattern or distribution.

There is no convincing explanation for the origin of the amyloid protein in the skin. Two theories, fibrillar body theory and secretory theory, have been proposed.[34] The fibrillar body theory states that damaged keratinocytes undergo filamentous degeneration by apoptosis and transformation by dermal fibroblasts and histiocytes and are converted into amyloid which deposits in the papillary dermis.[35] Secretion theory describes the deposition of amyloid from the degenerated basal keratinocytes at the dermoepidermal junction which eventually drops into the papillary dermis through the damaged lamina densa of basal layer.[36] Chang et al.[9] suggested that keratinocyte destruction in cutaneous amyloidosis may occur as an initial result of apoptosis as apoptotic keratinocytes were seen in the spinous layer and the dermoepidermal junction just above the amyloid deposits.[37] In our study, we found necrotic keratinocytes with pyknotic nuclei in five specimens overlying subepidermal amyloid, but their contribution toward the formation/localization of amyloid remains a matter of speculation. Additionally, there was focal disruption of the basal layer with pigmentary incontinence in only a few cases. No amyloid was detected around blood vessels or other cutaneous appendages. Similar features of thinning of epidermis, moderate acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, focal distribution of the basal layer with pigmentary incontinence as observed by us have been consistently described.[24,27,38,39] Amyloid on H&E stain shows amorphous eosinophilic masses and small deposits of amyloid can be missed with routine H&E stains.[39] Congo red produces an apple green birefringence under a polarizing microscope and is the most specific stain for detection of amyloid.[3,19] We observed an increased rate of detection of amyloid with Congo red and polarized light confirming its superiority for staining amyloid on histological sections

The hyperpigmentation which sometimes involves large surface areas of the upper back, arms and legs poses an important aesthetic problem. In general, the treatment of PLCA is disappointing. Topical corticosteroids with or without occlusive dressings and photoprotection can be used to treat mild cases. A topical application of 10% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) has been advocated for treatment but results have been equivocal.[40,41] Ultraviolet B (UVB) therapy has also been used with some success in the treatment of both macular and papular amyloidosis.[42] Etretinate and acitretin therapy has been beneficial in some cases,[43,44] but the condition seems to relapse after the treatment is stopped.[45] Treatment modalities like cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine[46] and dermabrasion[47] have a limited therapeutic efficacy. The Q-switched Nd-YAG laser (532 nm and 1064 nm) has shown positive response in the reduction of pigmentation in MA. In a study by Ostovari et al.,[48] 90% of patients with MA demonstrated more than 50% reduction in their pigmentation with the Q-switched Nd-YAG laser. A recently discovered cytokine, interleukin (IL)-31, has been proposed to play a role in itching[49] and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of itchy dermatosis such as PLCA (sporadic and familial).[50] This hypothesis has led to research of newer pharmacological therapies targeting IL-31 receptor in the management of PLCA and various other itchy dermatoses. A study by Clos et al. on a mouse model of cutaneous amyloidosis describes the use of conformational antibodies directed against amyloid, to facilitate antibody-mediated clearance of amyloid deposits in the skin. It is achieved by direct intradermal injection of these antiamyloid antibodies.[51]

Conclusion

The parameters collected and collated by us on this chronic, persistent and cosmetically disfiguring disease support the findings of the previous workers in relation to adult age of onset, preponderance of female sex, earlier onset in women and more frequent involvement of upper back and extensors of arms and the presence of symptoms of itching. Sun exposure did seem to play an important role in the localization of disease. Contrary to previous reports, MA in our study was observed in a majority of patients of comparatively lighter skin than in those with a higher skin phototype. The observation about the role of friction could not be conclusively supported or negated. Histopathology of the tissue specimens corroborates previous studies that the use of special stains increases the sensitivity of detecting amyloid in more specimens. Lack of clear-cut etiological factors makes it difficult to suggest a reasonable therapeutic modality. For want of the requisite information on the natural course and definitive etiology the disease, MA remains an enigma and a source of concern for the suffering patients and physicians.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Palitz LL, Peck S. Amyloidosis cutis: A macular variant. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;65:451–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1952.01530230075007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habermann MC, Montenegro MR. Primary cutaneous amyloidosis: Clinical, laboratorial and histopathological study of 25 cases. Identification of gammaglobulins and C3 in the lesions by immunofluorescence. Dermatologica. 1980;160:240–8. doi: 10.1159/000250500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.al-Ratrout JT, Satti MB. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: A clinicopathologic study from Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:428–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lines RR, 3rd, Hansen RC. A hyperpigmented, rippled eruption in a Hispanic woman: Macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:383–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.133.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djuanda A, Wiryadi BE, Sularsito SA, Hidayat D. The epidemiology of cutaneous amyloidosis in Jakarta (Indonesia) Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1988;17:536–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eswaramoorthy V, Kaur I, Das A, Kumar B. Macular amyloidosis: Etiological factors. J Dermatol. 1999;26:305–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1999.tb03476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasi A, Khatami A, Javaheri SM. Macular amyloidosis: An assessment of prevalence, sex, and age. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:898–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kibbi AG, Rubeiz NG, Zaynoun ST, Kurban AK. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:95–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb03245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang YT, Wong CK, Chow KC, Tsai CH. Apoptosis in primary cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:210–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1999.02651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shanon J, Sagher F. Interscapular cutaneous amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:195–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanigaki T, Hata S, Kitano Y, Nomura M, Sano S, Endo H, et al. Unusual pigmentation on the skin over trunk bones and extremities. Dermatologica. 1985;170:235–9. doi: 10.1159/000249539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somani V, Shailaja H, Sita V, Razvi F. Nylon friction dermatitis: A Venereol distinct subset of macular amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 1995;61:145–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong CK. Cutaneous amyloidoses. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:273–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanon J. Cutaneous amyloidosis associated with atopic disorders. Dermatologica. 1970;141:297–302. doi: 10.1159/000252484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onuma L, Vega M, Arenas R, Dominguez L. Friction amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto K, Kobayashi H. Histogenesis of amyloid in the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:165–71. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198000220-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siragusa M, Ferri R, Cavallari V, Schepis C. Friction melanosis, friction amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, towel melanosis: Many names for the same clinical entity. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:545–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahdah MJ, Kurban M, Kibbi AG, Ghosn S. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: A sign of immune dysregulation? Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:419–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breathnach SM. Amyloid and amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaynoun S, Erabi M, Kurban A. Letter: Macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:583. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1973.01620250063030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bedi TR, Datta BN. Diffuse biphasic cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatologica. 1979;158:433–7. doi: 10.1159/000250794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourke JF, Berth-Jones J, Burns DA. Diffuse primary cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:641–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb14880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajagopalan K, Tay CH. Familial lichen amyloidosis: Report of 19 cases in 4 generations of a Chinese family in Malaysia. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:123–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb16186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black MM, Jones EW. Macular amyloidosis. A study of 21 cases with special reference to the role of the epidermis in its histogenesis. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurban AK, Malak JA, Afifi AK, Mire J. Primary localized macular cutaneous amyloidosis: Histochemistry and electron microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:52–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb07179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brownstein MH, Hashimoto K. Macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:50–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkataram MN, Bhushnurmath SR, Muirhead DE, Al-Suwaid AR. Frictional amyloidosis: A study of 10 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:176–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramirez-Santos A, Labandeira J, Monteagudo B, Toribio J. Lichen amyloidosus without itching indicates that it is not secondary to chronic scratching. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:561–2. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto K, Ito K, Kumakiri M, Headington J. Nylon brush macular amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:633–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black MM, Maibach HI. Macular amyloidosis simulating naevoid hyperpigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 1974;90:461–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb06435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu JJ, Su YN, Hsiao CH, Jee SH, Tjiu JW, Chen JS. Macular amyloidosis presenting in an incontinentia pigmenti-like pattern with subepidermal blister formation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:635–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbas O, Ugent S, Borirak K, Bhawan J. Linear macular amyloidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1446–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho MH, Chong LY. Poikiloderma-like cutaneous amyloidosis in an ethnic Chinese girl. J Dermatol. 1998;25:730–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1998.tb02492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horiguchi Y, Fine JD, Leigh IM, Yoshiki T, Ueda M, Imamura S. Lamina densa malformation involved in histogenesis of primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:12–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12611384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi H, Hashimoto K. Amyloidogenesis in organ-limited cutaneous amyloidosis: An antigenic identity between epidermal keratin and skin amyloid. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;80:66–72. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases: Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:149–71. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70069-6. quiz 72-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li WM. Histopathology of primary cutaneous amyloidoses and systemic amyloidosis. Clin Dermatol. 1990;8:30–5. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(90)90085-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verga U, Fugazzola L, Cambiaghi S, Pritelli C, Alessi E, Cortelazzi D, et al. Frequent association between MEN 2A and cutaneous lichen amyloidosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59:156–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macsween RM, Saihan EM. Nylon cloth macular amyloidosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:28–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1997.1770598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozkaya-Bayazit E, Kavak A, Gungor H, Ozarmagan G. Intermittent use of topical dimethyl sulfoxide in macular and papular amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:949–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandhi R, Kaur I, Kumar B. Lack of effect of dimethylsulphoxide in cutaneous amyloidosis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2002;13:11–4. doi: 10.1080/09546630252775180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudson LD. Macular amyloidosis: Treatment with ultraviolet B. Cutis. 1986;38:61–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hernandez-Nunez A, Dauden E, Moreno de Vega MJ, Fraga J, Aragues M, Garcia-Diez A. Widespread biphasic amyloidosis: Response to acitretin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:256–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marschalko M, Daroczy J, Soos G. Etretinate for the treatment of lichen amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:657–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1988.01670050015008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aram H. Failure of etretinate (RO 10-9359) in lichen amyloidosus. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1986.tb02224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Behr FD, Levine N, Bangert J. Lichen amyloidosis associated with atopic dermatitis: Clinical resolution with cyclosporine. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:553–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong CK, Li WM. Dermabrasion for lichen amyloidosus: Report of a long-term study. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:302–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ostovari N, Mohtasham N, Oadras M, Malekzad F. 532-nm and 1064-nm Q-switched Nd: YAG laser therapy for reduction of pigmentation in macular amyloidosis patches. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:442–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Q, Putheti P, Zhou Q, Liu Q, Gao W. Structures and biological functions of IL-31 and IL-31 receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:347–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka A, Arita K, Lai-Cheong JE, Palisson F, Hide M, McGrath JA. New insight into mechanisms of pruritus from molecular studies on familial primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1217–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clos AL, Lasagna-Reeves CA, Wagner R, Kelly B, Jackson GR, Kayed R. Therapeutic removal of amyloid deposits in cutaneous amyloidosis by localised intra-lesional injections of anti-amyloid antibodies. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:904–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]