Abstract

Introduction:

Surgical methods for treatment of vitiligo include punch grafts, blister grafts, follicular grafts and cultured melanocyte grafts. The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of suction blister grafts for treatment of vitiligo, without the use of phototherapy.

Materials and Methods:

This clinical trial study was conducted on 10 patients with vitiligo that was resistant to usual treatments and with limited involvement in the affected sites. We used cryotherapy and a manual suction device for blistering at the recipient and donor sites, respectively. The blister was separated and fixed with sutures and a dressing to the recipient site. Repigmentation of lesions was evaluated monthly for 6 months after treatment. Repigmentation rates higher than 90%, between 71%–90%, from 51%–70%, and less than 50% were graded as complete, good, moderate, and poor, respectively.

Results:

Ten patients (five females with a mean age of 23.2±3.96 years and five males with a mean age of 30.60±4.15 years) were enrolled in the study. Reponses to treatment after a 6-month follow-up were ‘complete,’ ‘good,’ and ‘moderate’ in 7 (70%), 1 (10%), and 2 (20%) patients, respectively.

Conclusion:

With this technique, patients with restricted sites of involvement, that did not respond to the usual treatments showed very good repigmentation without any additional phototherapy over a 6-month follow-up; moreover, there were no side effects such as scarring.

Keywords: Blister graft, PUVA, repigmentation, vitiligo

Introduction

Vitiligo is an acquired pigmentary disorder that is caused by loss of melanin, resulting in depigmented skin, mucous membrane, eyes, and sometimes hair bulbs. It occurs worldwide, with a prevalence of 0.1%–2% in various populations.[1,2] A number of therapeutic options for regimentation are available. Narrow-band UVB is effective and considered by many to be the first choice for most patients.[3–6] Psoralens and UVA treatment is the most important treatment for generalized vitiligo that affects more than 10%–20% of the cutaneous surface. For localized vitiligo, topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors are the most valuable treatments.[4]

Surgical techniques have also been introduced for stable, segmental and unresponsive vitiligo. A number of dermatosurgery techniques are available to promote repigmentation of vitiligo in adults and children, such as mini- or punch grafts, split-thickness skin grafts, cultured epidermal sheets, cultured melanocyte suspensions, follicular grafts and suction blister grafts.[7–18] Among these methods, the highest success rates have been achieved with split-thickness skin grafts and epidermal blister grafts. For better results, phototherapy or photochemotherapy of donor sites can also be performed after or before grafting.[19–21] Because phototherapy is not without limitations and side effects, the aim of the present study was to evaluate treatment of stable vitiligo in Iranian patients using suction blister grafting, without phototherapy either before or after grafting.

Materials and Methods

The patients enrolled in this study had limited vitiligo that was stable but resistant to common treatments. They were admitted to the dermatology ward of the Imam Reza Hospital, Mashhad, Iran. Patients excluded from the study included those with unstable disease and those under 18 years (because of the pain associated with surgical procedures). All patients were advised to discontinue previous treatments at least 1 month before the grafting procedure to minimize any possible drug effects.

The day before surgery, relatively intense cryotherapy was done at the vitiligo-affected recipient site. Cryotherapy was performed with liquid nitrogen and a cotton swab through two cycles of 15–20 seconds, with 20 seconds intervals. On the day of surgery, a donor site was selected on the medial aspect of the thigh (with normal skin) and the area was cleaned first with povidone iodine and then with normal saline. After local anesthesia, the site was attached to the vacuum device and the device piston was pulled steadily to produce a high negative pressure. For blister induction at the donor site, we used a YUEXIAO™ vacuum device (made in China) that is originally intended for relieving muscle and joint pain [Figure 1]. After about 3–4 hours of application of suction, the blister was ready and was removed by scalpel or scissors and placed in a dish containing normal saline. The donor site was dressed with antibiotic ointment and Vaseline gauze. After removing the roof of the donor and recipient site blister, donor graftable epidermis was placed on the recipient site, sutured with 6-0 nylon and then covered with antibiotic ointment and Vaseline gauze. To prevent shifting of the graft, wet sterile cotton was applied over the area and covered with sterile gauze, with the dressing firmly bound in place with a compression bandage. After surgery, a 7-day course of antibiotic (cephalexin 500 mg qid orally) was given and the patient was advised to keep the site immobilized for a week. The dressing was changed after a week and sutures were removed after 2 weeks. Finally, repigmentation rates were evaluated by comparing images of the lesions every month for 6 months after surgery. Repigmentation rates >90%, 71%–90%, 51%–70%, and <50% were graded as ‘complete,’ ‘good,’ ‘moderate,’ and ‘poor,’ respectively.

Figure 1.

The vacuum device that was used for this study

Results

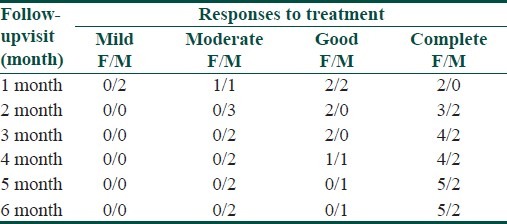

In this study, 10 patients (5 female and 5 male) with stable vitiligo were evaluated for response following suction blister grafting, without pre- or post-graft phototherapy. The mean ages of our male patients and female patients were 30.60±4.15 and 23.20±3.96, respectively. Responses to treatment at different follow-up evaluations are presented in Table 1. No gender differences were noted in the response to treatment, although ‘complete’ responses were more common in men and ‘moderate’ responses were more common in women. Responses to treatment were mild, moderate, good, and complete in 20%, 20%, 40%, and 20% of patients, respectively, after 1 month of follow- up. After 5 and 6 months of follow-up, moderate, good, and complete responses were found in 20%, 10%, and 70% of patients, respectively [Figure 2].

Table 1.

Responses to blister graft surgery at different follow-up evaluations in female (F) and male (M) patients

Figure 2.

(a) before the blister graft, (b) 1 month after graft surgery, and (c) 6 months after graft surgery

Discussion

Vitiligo should initially be treated with medical therapy. When the therapy fails in spite of all appropriate interventions, surgical treatment may be indicated.[3] Autologous skin grafts can be obtained from uninvolved skin using several techniques, including a number of dermatosurgery techniques.[1] Each method has its advantages and disadvantages. The mini-graft is the simplest, least expensive, and most commonly used, but it has the highest rate of adverse effects, with 35% risk of cobblestone appearance at the recipient site and hypopigmentation and keloid formation at the donor site.[22,23] Thin split-thickness grafting has the highest mean success rate (87%) according to a systematic review by Njoo et al.[19] Transplantation of cells cultured in vitro from a small piece of donor skin is also used for treatment of large areas by expanding the melanocyte population; however, this method is very expensive and requires special and advanced laboratory facilities that is now available only at a few academic centers.[3] Suction blister grafting is accomplished by suction of viable epidermis from dermis and pigmented epidermis is used for coverage of achromic areas. In most studies in the literature, when epithelization was completed (usually after 1 week) phototherapy was used to induce proliferation and migration of melanocytes in the recipient sites.[24–26] The repigmentation rate in these studies, according to the review by Njoo et al., was 87%, whereas Ozdemi et al. reported rates between 25%–65%.[19,27] In a similar study in our region, Maleki et al. evaluated ten patients with refractory vitiligo who were treated by suction blister graft and subsequent PUVA therapy and reported over 90% repigmentation in seven patients.[28] Nanda et al. evaluated six patients with resistant eyelid vitiligo who underwent suction blister grafting without phototherapy (as performed in the present study) and reported repigmentation in all cases.[29]

In our study, blister grafting without phototherapy showed excellent results in 70% of our patients. The advantages of this technique include low cost, absence of scarring and the possibility of reusing the donor site. The disadvantages are that it is time consuming, painful and not suitable for large areas, uneven surfaces and the palm. Our study shows that this technique is effective and safe for treating stable and limited vitiligo especially when phototherapy is not available.

Acknowledgment

The authors greatly appreciate the financial support provided by the Research Council of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran for this student thesis (2160). We thank Dr Musa Mirshekar and all the dermatology residents of Imam Reza Hospital for their assistance in this evaluation. We also thank Hadis Yousefzadeh for her assistance in preparing this paper.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Research Council of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Halder RM, Taliaferro SJ. Vitiligo. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 611–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majumder MP. Genetic and prevalence of vitiligo vulgaris. In: Hann BK, Nordlund JJ, editors. Vitiligo. Hoboken New Jersey: Blackwell Sience; 2000. pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anstey AV. Disorders of Skin Colour. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths CEM, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. Vol. 58. Hoboken New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortonne JP. Pigmentary disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorrizo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. pp. 913–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westerhof W, Nieuweboer-Krobotova L. Treatment of vitiligo withUV-B radiation vs topical psoralen plus UV-A. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1525–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherschum L, Kim JI, Lim HW. Narrow-band ultraviolet B is a useful and well tolerated treatment for vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:999–1003. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falabella R, Barona MI. Update on skin repigmentation therapies in vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:42–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal K, Agrawal A. Vitiligo: Repigmentation with dermabrasion and thin split thickness skin graft. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falabella R. Repigmentation of segmental vitiligo by autologous minigrafting. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:514–21. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khunger N, Kathuria SD, Ramesh V. Tissue grafts in vitiligo surgery - past, present, and future. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:150–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.53196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahiri K. Evolution and evaluation of autologous mini punch grafting in vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:159–67. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.53195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lahiri K, Malakar S, Sarma N, Banerjee U. Repigmentation of vitiligo with punch grafting and narrow-band UV-B (311 nm) a prospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2005;45:649–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauthier Y, Surleve-Bazeille JE. Autologous grafting with noncultured melanocytes: A simplified method for treatment of depigmented lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:191–4. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70024-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerra L, Capurro S, Melchi F, Primsvera G, Bondanza S, Cancedda R, et al. Treatment of ‘stable’ vitiligo by Timedsurgery and transplantation of cultured epidermal autografts. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1380–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.11.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim CY, Yoon TJ, Kim TH. Epidermal grafting after chemical epilation in the treatment of vitiligo. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:855–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falabella R. Grafting and transplantation of melanocytes for repigmenting vitiligo and other types of leukoderma. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:363–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koga M. Epidermal grafting using the tops of suction blisters in the treatment of vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1656–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong W, Hu DN, Qian GP, McCormick SA, Xu AE. Treatment of vitiligo in children and adolescents by autologous cultured pure melanocytes transplantation with comparison of efficacy to results in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:538–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Njoo MD, Westerhof W, Bos JD, Bossuyt PM. A systematic review of autologous transplantation methods in vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. 1998;34:1543–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.12.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hann SK, Im S, Bong HW, Park YK. Treatment of stable vitiligo with autologous epidermal grafting and PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:943–8. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suga Y, Butt KI, Takimoto R, Fujioka N, Yamada H, Ogawa H, et al. Successful treatment of vitiligo with PUVA-pigmented autologous epidermal grafting. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:518–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babu A, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ. Punch grafting versus suction blister epidermal grafting in the treatment of stable lip vitiligo. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:166–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusfianti M, Wirohadidjodjo YW. Dermatosurgical techniques for repigmentation of vitiligo. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:411–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee AY, Jang JH. Autologous epidermal grafting with PUVA-irradiated donor skin for the treatment of vitiligo. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:551–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ortonne JP, MacDonald DM, Micoud A, Thivolet J. PUVA-induced repigmentation of vitiligo: A histochemical (split-DOPA) and ultrastructural study. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb15285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awad SS, Abdel-Raof H, El-Din WH, El-Domyati M. Epithelial grafting for vitiligo requires ultraviolet A phototherapy to increase success rate. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:119–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozdemir M, Cetinkale O, Wolf R, Kotogyan A, Mat C, Tüzün B, et al. Comparison of two surgical approaches for treating vitiligo: A preliminary study. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:135–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maleki M, Javidi Z, Ebrahimi_rad M. Treatment of Vitiligo with Blister Grafting Technique. Iranian J Dermatol. 2008;11:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nanda S, Relhan V, Grover C, Reddy BS. Suction blister epidermal grafting for management of eyelid vitiligo. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:391–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]