Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a chronic, progressive disease of the pulmonary vasculature with a high morbidity and mortality. Its pathobiology involves at least three interacting pathways – prostacyclin (PGI2), endothelin, and nitric oxide (NO). Current treatments target these three pathways utilizing PGI2 and its analogs, endothelin receptor antagonists, and phosphodiesterase type-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors. Inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) is approved for the treatment of hypoxic respiratory failure associated with pulmonary hypertension in term/near-term neonates. As a selective pulmonary vasodilator, iNO can acutely decrease pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance without affecting cardiac index or systemic vascular resistance. In addition to delivery via the endotracheal tube, iNO can also be administered as continuous inhalation via a facemask or a pulsed nasal delivery. Consistent with a deficiency in endogenously produced NO, long-term pulsed iNO dosing appears to favorably affect hemodynamics in PAH patients, observations that appear to correlate with benefit in uncontrolled settings. Clinical studies and case reports involving patients receiving long-term continuous pulsed iNO have shown minimal risk in terms of adverse events, changes in methemoglobin levels, and detectable exhaled or ambient NO or NO2. Advances in gas delivery technology and strategies to optimize iNO dosing may enable broad-scale application to long-term treatment of chronic diseases such as PAH.

Keywords: drug, hypertension, inhalation administration, nitric oxide, pulmonary arterial hypertension, pulmonary circulation, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary/physiopathology, pulse therapy, vasodilator agents

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a chronic, progressive disease of the pulmonary vasculature resulting in right ventricular failure and death, if untreated.[1,2] PAH is defined by the following: a resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥25 mmHg; pulmonary capillary wedge pressure or left ventricular end diastolic pressure ≤15 mmHg; and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) ≥3 Wood units.[2] PAH can be idiopathic, heritable, or associated with other conditions, such as connective tissue diseases (CTDs).[3,4]

The prevalence of PAH was estimated as 26–52 cases per million from the Scottish epidemiological study; a more conservative lower-bound estimate from the French PAH Registry reports 5–25 cases per million.[5,6] Prevalence is greater in high-risk groups, such as patients with CTDs, congenital heart disease (repaired and unrepaired), human immunodeficiency virus, and portal hypertension.[7–9]

Pulmonary arterial hypertension: Mortality and unmet medical need

The mortality with PAH remains high despite treatment advances over the past several decades. In the 1980s, the 5-year survival rate for idiopathic PAH (IPAH; formerly termed “primary pulmonary hypertension”) was 34% in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Registry; although 5-year survival has increased to ≈60% using currently available drugs, the mortality remains unacceptable.[4] Patients in the NIH registry in the 1980s were treated with the conventional therapy available at the time, including diuretics, digoxin, supplemental oxygen, warfarin, and calcium channel blockers (if clinically indicated).[4] Prior to 1995, no drugs were approved for PAH. However, there are currently eight drugs approved for the treatment of PAH: intravenous (IV) epoprostenol, IV/subcutaneous (SC) treprostinil, inhaled treprostinil, inhaled iloprost, oral bosentan, oral ambrisentan, oral sildenafil, and oral tadalafil. A meta-analysis of all randomized, controlled PAH trials published through 2008 suggested that with these available PAH-specific treatments, mortality has decreased 43% (RR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.35–0.92; P=0.023).[10] Despite these improvements in survival rates, a significant unmet medical need remains: PAH continues to progress with no cure.

Patients with PAH also report severe impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQOL), including poor general and emotional health, and impaired physical functioning.[9] These impairments to HRQOL with PAH are comparable and not infrequently greater than those reported in patients with severely debilitating conditions such as spinal cord injury or cancers unresponsive to therapy.[9] Improvement in HRQOL scores has been reported (e.g., increased exercise capacity and physical functioning) utilizing the currently available PAH-specific drugs.[11–13]

Pathobiology

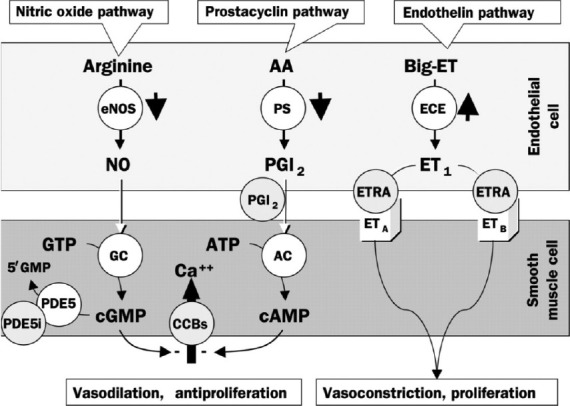

The postulated pathobiology of PAH involves interactions between the prostacyclin (PGI2), endothelin (ET-1), and nitric oxide (NO) pathways, in addition to a host of other pathways (Fig. 1).[2,14–16] Specific mechanisms responsible for the development and progression of PAH include the following: reduced PGI2 synthase; increased ET-1 expression; decreased NO synthase; elevated plasma levels and low platelet 5-hydroxytryptamine levels; downregulation of potassium channels of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells; activity of autoantibodies and proinflammatory cytokines; and prothrombotic states arising from endothelial, coagulation, and fibrinolytic cascade/platelet dysfunction.[16] These changes give rise to a complex process of pathobiologic changes in the pulmonary vascular bed, including endothelial dysfunction, vasoconstriction, vascular remodeling, and in situ thrombosis.[2]

Figure 1.

Pathways involved in the development and maintenance of pulmonary arterial hypertension. AA: arachidonic acid; ET: endothelin; eNOS: endothelial NO synthase; PS: prostacyclin synthase; ECE: endothelinconverting enzyme; PGI2: prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin); ETRA: endothelin receptor agonist; GTP: guanylate triphosphate; GC: guanylate cyclase; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; AC: adenylyl cyclase; CCB: calcium channel blocker; cGMP: cyclic guanylate monophosphate; cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PDE5: phosphodiesterase-5; PDE5i: PDE5 inhibitor. Reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 358, Jocelyn Dupuis, Endothelin-receptor antagonists in pulmonary hypertension, pages no. 1113–1114, Copyright (2001), with permission from Elsevier[15] and with permission from Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Volume 84, Michael D. McGoon and Garvan C. Kane, pulmonary hypertension: diagnosis and management, pp 191–207, Copyright Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (2009).[16]

Pharmacologic targets of currently approved treatments for PAH

Current PAH treatment approaches include PGI2 and its analogs, ET-1 receptor antagonists (ERAs), and phosphodiesterase type-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors.[17] Combination trials have demonstrated additive and/or synergistic benefit by targeting more than one pathway.[17] Prostanoid monotherapy (epoprostenol, treprostinil, and iloprost) improves symptoms, exercise capacity, and hemodynamics.[17] Increased survival was also demonstrated in IPAH/heritable PAH (HPAH) with IV epoprostenol. However, common side effects with prostanoids include headache, flushing, nausea, jaw pain, diarrhea, skin rash, and musculoskeletal pain. Treatment with PGI2 and its analogs often requires continuous intravenous parenteral infusion, which can cause blood stream infections and/or thromboembolic events that can be life threatening.[2]

Endothelin-1 exerts vasoconstrictor and mitogenic effects, whereas ERAs (i.e., bosentan and ambrisentan) improve exercise capacity, functional class, and hemodynamics.[2,8] Adverse effects include acute hepatotoxicity, anemia, and fluid retention. Additionally, ERAs may cause testicular atrophy and male infertility. Use of bosentan requires monthly liver function tests and two modes of birth control, as it has been shown to cause severe fetal toxicity in animal studies.[2,18]

In three randomized trials, the PDE-5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil improved exercise capacity and hemodynamics (either as monotherapy or as add-on therapy).[8,11,17] Both agents cause pulmonary vasodilation.[8] Side effects include headache, flushing, and dyspepsia and are generally related to systemic vasodilation. Epistaxis has also been reported with sildenafil use in PAH.[8,11] Prostacyclin analogs, ERAs, and PDE-5 inhibitors are the mainstays of current PAH treatment; however, all have systemic effects in addition to their pulmonary effects that can cause untoward side effects.[19] An optimal agent for PAH therapy remains to be identified.[17]

Inhaled nitric oxide

Inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) is a selective pulmonary vasodilator that can acutely decrease pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in neonates with hypoxic respiratory failure associated with pulmonary hypertension.[20] Nitric oxide regulates vascular smooth muscle tone and increases blood flow to regions of the lungs with normal ventilation/perfusion ratios by dilating pulmonary vessels in better-ventilated areas.[21] After inhalation, NO is absorbed systemically, with the majority of NO traversing the pulmonary capillary bed and combining with 60-100% oxygen-saturated hemoglobin.[20] The effect of iNO is localized to the lung, as once absorbed iNO is rapidly oxidized by hemoglobin to form nitrite, which interacts with oxyhemoglobin, leading to the formation of nitrate and methemoglobin (metHb).[20,22] This metabolic production of metHb is a potential toxic effect of iNO treatment. While doses <100 ppm most often result in insignificant metHb levels in adults and children, methemoglobinemia has been reported with 80 ppm when exposure was >18 hours.[23]

Inhaled NO is currently indicated for the treatment of term/near-term neonates (>34 weeks gestation) with hypoxic respiratory failure associated with pulmonary hypertension (PH). The recommended dose is 20 ppm delivered via constant concentration during inspiration for up to 14 days or until hypoxia has resolved.[20]

Inhaled NO has also been used as an agent for acute vasodilator testing (AVT) as part of the evaluation of PAH patients; doses of 20–80 ppm for 5–10 minutes are typically used.[2,24] Detecting an acute response with AVT is useful in selecting patients who should be considered for initial treatment with high-dose oral chronic calcium channel blockade; AVT response may also be helpful in predicting long-term prognosis with medical therapy and following surgical interventions, such as heart or heart–lung transplantation.[24] Administered as continuous inhalation via face mask, iNO can selectively decrease PAP and PVR without reducing cardiac index or systemic vascular resistance.[24] Inhaled NO has also been used in other contexts, such as perioperatively for cardiac surgery,[25–33] right heart failure after insertion of the left ventricular assist device,[34–37] cardiogenic shock due to right ventricle myocardial infarction,[38] and pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury.[39–44]

Because the pulmonary vasodilator effects of NO are transient, it is administered continuously during inspiration, with careful monitoring of NO and NO2 concentrations.[20] Nitric oxide gas can be safely administered in both intubated and nonintubated patients.[45] The pulmonary selectivity of iNO may render it useful as an adjunct to other therapies that are dose limited by their systemic effects.

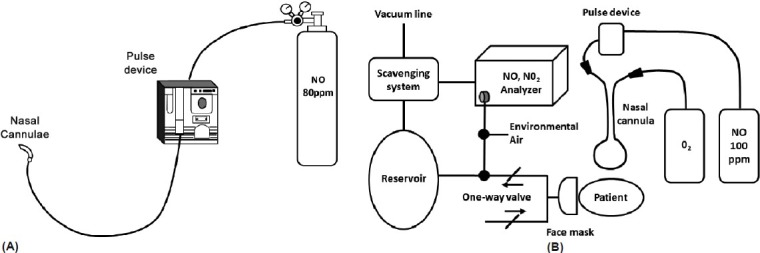

Inhaled NO has also been administered long term via pulsed nasal delivery (ml/breath/h) in clinical trials; this method has been studied for continuous long-term outpatient as well as short-term inpatient treatment (Fig. 2).[46–49] This ambulatory administration method delivers a set, pulsed volume of NO at the beginning of each breath via a nasal cannula connected through a NO demand valve to a cylinder of up to 200 ppm NO in N2.[46–48] Both the continuous face mask and pulsed delivery via nasal cannula have comparable hemodynamic effects.[50] A potential theoretical advantage of iNO, in contrast to IV vasodilators, is its pulmonary selectivity (due to rapid hemoglobin-mediated inactivation).[22] Although prostanoids administered via inhalation appear to have less ventilation–perfusion mismatching than when administered intravenously/subcutaneously or orally, some degree of ventilation–perfusion mismatching persists; in addition, systemic spill-over can result in untoward systemic effects.[51–53]

Figure 2.

Examples of pulsed inhaled nitric oxide delivery systems used in clinical studies: (A) Ambulatory system. Reproduced with permission from the American College of Chest Physicians, Chest, Volume 109, Richard N. Channick, John W. Newhart, F. Wayne Johnson, Penny J. Williams, William R. Auger, Peter F. Fedullo, and Kenneth M. Moser, pulsed delivery of inhaled nitric oxide to patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: an ambulatory delivery system and initial clinical tests, pp 1545–1549, Copyright (1996), American College of Chest Physicians;[48] (B) Hospital system. Reprinted with permission from Internal Medicine, Volume 41, Osamu Kitamukai, Masahito Sakuma, Tohru Takahashi, Jun Nawata, Jun Ikeda, and Kunio Shirato, hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide using pulse delivery and continuous delivery systems in pulmonary hypertension, pp 429–434, Copyright The Japanese Society of Internal Medicine (2002).[49] iNO: inhaled nitric oxide NO2: nitrogen dioxide

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF INHALED NITRIC OXIDE AS LONG-TERM TREATMENT FOR PAH

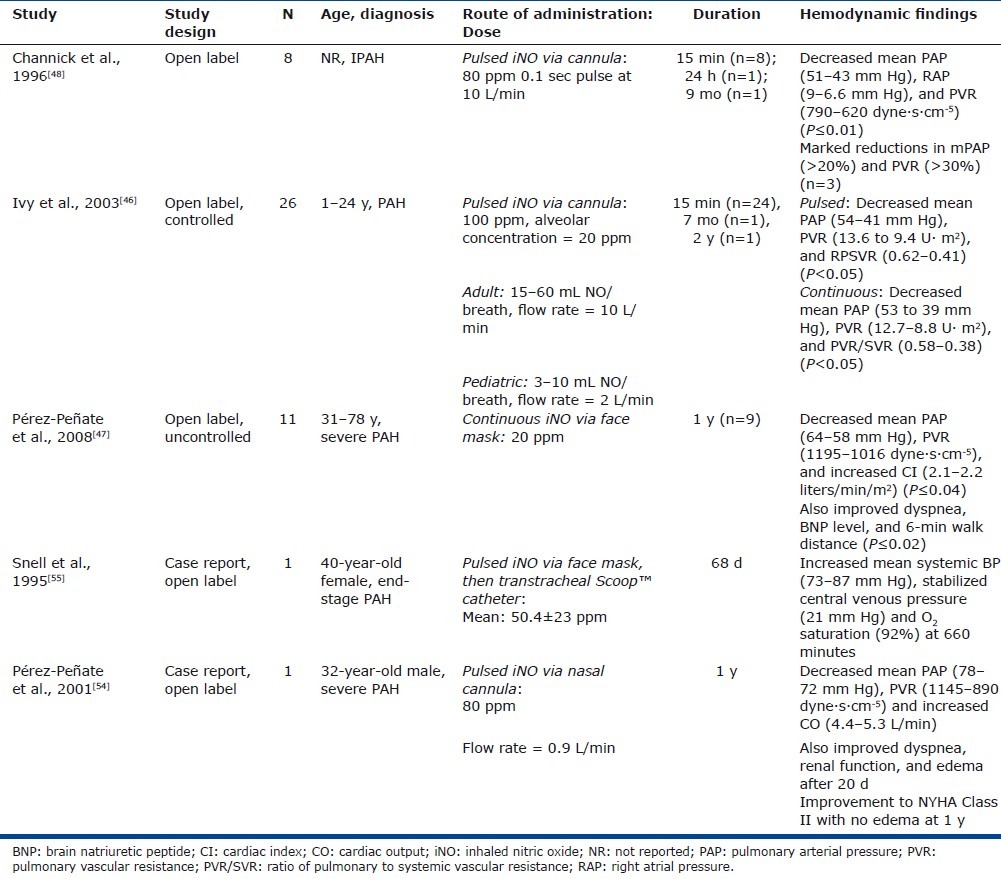

Long-term (>1 month) pulsed iNO dosing appears to favorably affect pulmonary hemodynamics findings[46–48,54,55] which, with other types of therapy, appear to correlate with benefit (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inhaled long-term nitric oxide use for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension

In a study of eight patients with IPAH, Channick et al. reported decreased mean PAP (mPAP), mean right atrial pressure (mRAP), and PVR (P ≤ 0.01) with short-term iNO treatment using an ambulatory NO delivery system via nasal cannula (Table 1).[48] No adverse symptoms and no changes in metHb levels were reported. One patient was discharged home on chronic pulsed iNO and reported no adverse effects after 9 months of treatment.

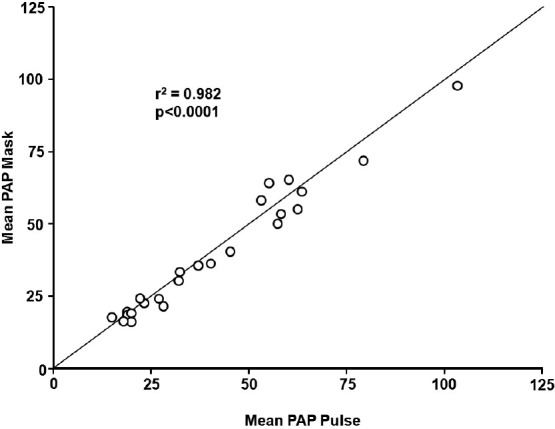

Ivy et al. also reported that in 26 children and young adults with PAH (short-term therapy, n=24; long-term therapy, n=2) constant concentration and pulsed delivery of NO (via nasal cannula) were equally effective in decreasing PAP and PVR (P<0.05 vs. baseline; Table 1; Fig. 3).[46] Adult and pediatric devices were studied, and the adult device delivered 15–60 ml NO per breath at a flow rate of 10 l/min while the pediatric device delivered 3–10 ml per breath at a flow rate of 2 l/minute. Two patients were discharged home on iNO using a pulsed device; 1 for 7 months and 1 for 2 years with no reported adverse events including no reports of syncope or near syncope.

Figure 3.

Correlation between mean pulmonary arterial pressure during mask delivery and pulsed nasal nitric oxide delivery. PAP: pulmonary artery pressure. Reprinted from The American Journal of Cardiology, Vol 92, D. Dunbar Ivy, Donna Parker, Aimee Doran, Donna Parker, John P. Kinsella, and Steven H. Abman, acute hemodynamic effects and home therapy using a novel pulsed nasal nitric oxide delivery system in children and young adults with pulmonary hypertension, pages no. 886–890, Copyright (2003), with permission from Excerpta Medica, Inc.[46]

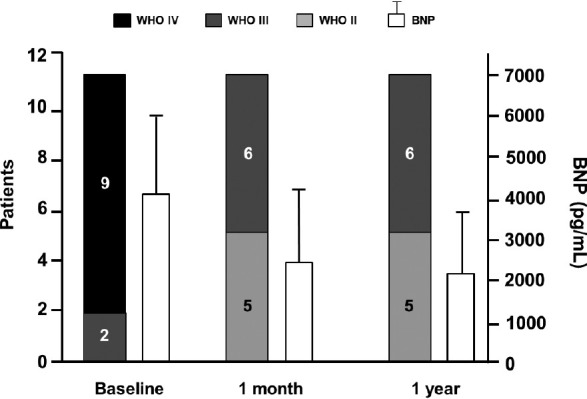

Long-term treatment with pulsed iNO was evaluated in 11 patients (7 with PAH and 4 with chronic thromboembolic PH) in an uncontrolled, open-label study. The study design included the addition of PDE-5 inhibitor (dipyridamole or sildenafil) for clinical worsening; this was suggested as a means to “stabilize and potentiate the effects of iNO” and to “potentially serve as rescue therapy in severe PH” (Table 1).[47] After 1 month of an ambulatory iNO system via nasal cannula, patients had an improvement in World Health Organization functional class concomitant with improvements in 6-minute walking distance (P=0.003), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level (P=0.02; Fig. 4).[47] One patient died from refractory right heart failure at month 8; 7 of the 11 patients had a PDE-5 inhibitor added at 6–12 months due to symptomatic deterioration. At the 1-year follow-up, 9 of the 11 patients reported durability of effect as observed after 1 month of therapy with associated significant improvements in mPAP, PVR, and CI. In addition, the significant improvements in 6-minute walking distance (P=0.003) and BNP levels (P=0.02) were maintained at the 1-year follow-up. There were no reports of NO air contamination, changes in metHb levels, adverse reactions, NO toxicity, or rebound PH from sudden withdrawal.[47]

Figure 4.

World Health Organization functional class and brain natriuretic peptide levels (mean±SD) at baseline compared with 1 month and 1 year after onset of iNO treatment. *In Patients 1 and 2, the measure was taken at 6 months. BNP: brain natriuretic peptide. Reprinted from The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Vol 27, Gregorio Miguel Pérez-Peñate, Gabriel Juliá-Serdà, Nazario Ojeda-Betancort, Antonio García-Quintana, Juan Pulido-Duque, Aurelio Rodríguez-Pérez, Pedro Cabrera-Navarro, Miguel Angel Gómez-Sánchez, Long-term inhaled nitric oxide plus phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors for severe pulmonary hypertension, Pages No. 1326–1332, Copyright (2008), with permission from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation.[47]

Two case reports have also examined long-term iNO administration in PAH patients, including its use as a “bridge to heart-lung or lung transplantation” (Table 1). A 40-year-old woman presented with end-stage IPAH and experienced severe dyspnea, right ventricular angina, oliguria, and syncope despite treatment with dopamine infusion and with prostacyclin. The patient then initiated treatment with pulsed iNO, initially via face mask and then transtracheal catheter, until she underwent heart-lung transplantation after 68 days of therapy.[55] The patient's condition appeared to stabilize on iNO treatment, although she had a hypotensive bradycardic event after 53 days, requiring reinitiation of intravenous prostacyclin. While iNO was administered, she was able to move about her room independently and participate in a physiotherapy exercise program. The explanted lungs revealed no evidence of NO toxicity.[55]

Another case reported the effects of 12 months of iNO administration in a 32-year-old man with IPAH (Table 1).[54] The patient presented with exertional dyspnea and anasarca, and was treated with long-term iNO monotherapy via an ambulatory system with nasal cannula. After 20 days, there was an improvement in dyspnea and gas exchange, and a resolution of the anasarca. After 12 months of continuous iNO, the patient remained clinically stable, with maintained hemodynamic improvement and no signs of toxicity or tachyphylaxis.[54]

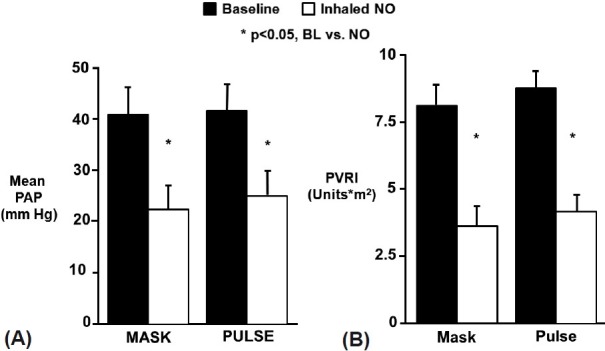

Ivy et al. reported that short-term pulsed nasal delivery utilizing constant concentration was as effective in lowering PAP and PVR as mask delivery in the acute setting in eight children with PAH (Fig. 5).[50] Based on the results of this study, the authors concluded that the practicality of long-term iNO therapy via pulsed flow nasal delivery is potentially dependent on four factors: (1) maintenance of sufficient iNO delivery; (2) improvement of hemodynamic derangements by nasal cannula at low flow rates; (3) effective delivery of nasal NO with minimal release of gas into the environment; and (4) minimized consumption of NO gas.[50] Aside from the reports involving long-term use summarized in Table 1, the practicality of pulsed delivery of iNO for improvement in oxygenation with less NO consumption and less environmental contamination has been demonstrated in several other studies.[56–58]

Figure 5.

Delivery of inhaled NO by continuous mask or pulsed nasal cannula was equally effective in lowering mean pulmonary artery pressure (A) and pulmonary vascular resistance index (B). PAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; PVRI: pulmonary vascular resistance index; iNO: inhaled nitric oxide; BL: baseline. Reprinted from The Journal of Pediatrics, Vol 133, D. Dunbar Ivy, Jeffrey L. Griebel, John P. Kinsella, and Steven H. Abman, acute hemodynamic effects of pulsed delivery of low flow nasal nitric oxide in children with pulmonary hypertension, Pages No. 453–456, Copyright (1998), with permission from Mosby, Inc.[50]

ROLES FOR LONG-TERM INHALED NITRIC OXIDE IN THE TREATMENT OF PULMONARY ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION

Potential uses of pulsed, long-term iNO treatment in PAH patients include the following: use as a bridge to transplantation; a means of deferring transplantation; and as an add-on therapy to currently approved PAH drugs[2,45] with potential additive or synergistic effects.[59,60] It is important to note that NO synthase 3 (NOS3) has been reported to be decreased in PAH patients; in uncontrolled observational studies, PAH has been associated with impaired NO release, at least in part, due to reduced expression of NOS3 in the vascular endothelium of pulmonary arterioles.[61] As a result, long-term administration of iNO may serve both as a selective pulmonary vasodilator and as NO replacement therapy, making it a logical choice for clinical evaluation as add-on therapy.

Safety considerations

A potential safety concern with iNO treatment is rebound PH upon its sudden discontinuation after longer-term (days) use[20,62]; this phenomenon is well known and has been well documented in neonates and in postoperative cardiac surgery patients. Such patients include cardiac transplant recipients, children undergoing surgery for congenital heart disease, and adults with mitral and/or aortic stenosis. Gradual weaning of iNO has been shown to minimize the potential for rebound PH in the acute ICU setting.[45] Davidson et al. presented a method to safely withdraw iNO in infants treated for hypoxic respiratory failure, recommending the gradual weaning of iNO down to 1 ppm prior to treatment discontinuation.[63] Further research has implicated the rapid degradation of smooth muscle intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) by local phosphodiesterases (PDEs) as a primary mechanism for this rebound effect. As a result, initial approaches focused on the use of dipyridamole, a PDE-5 inhibitor, as a means for reducing rebound PH after iNO withdrawal. Ivy et al. first demonstrated this concept in a prospective study of 23 children treated with iNO after surgery for congenital heart disease.[64] Later studies examined the role of sildenafil, another PDE-5 inhibitor, in the context of rebound PH, showing that its introduction prior to withdrawal of iNO resulted in facilitation of iNO weaning, as well as prevention/amelioration of rebound PH effects in infants and children with PH after congenital heart disease surgery, persistent PH of the newborn, and other abnormalities.[65–68] As with any approach, it is important to consider patient characteristics and treatment familiarity, availability, and contraindications, as well as optimal ventilation and supplemental vasodilators, when initiating treatment for rebound PH.[66]

A review of the published literature on long-term iNO dosing in PAH patients has not revealed any reports of rebound PH crises or associated symptoms (e.g., syncope, systemic arterial oxygen desaturation, systemic hypotension, bradycardia, or cardiac arrest).[46–48,54,55] It may be that more acute initial rise in PAP is associated with a greater likelihood and severity of a rebound effect occurring with acute iNO withdrawal. This may explain why the rebound phenomenon has been observed in the acute care setting (e.g., neonates with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn and high risk postoperative cardiothoracic surgical patients) and not observed in the more chronic setting of PAH or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[69]

Cytotoxicity is another possible concern with iNO and its oxidized derivatives (principally NO2). Nitric oxide may be directly toxic to alveolar and vascular tissue; therefore, it has been proposed that NO be stored in combination with nitrogen and blended with oxygen at the time of administration to prevent oxidation to toxic products, in addition to maintaining NO2 levels <5 ppm.[23,70]

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In summary, uncontrolled observational studies of long-term use (>1 month) of continuous pulsed iNO (as monotherapy or as part of combination therapy) in a total of 14 patients with PAH across five studies[46–48,54,55] have reported no significant adverse events, no elevated metHb levels, and no detectable exhaled or ambient NO or NO2. In one study, a patient experienced three episodes of severe epistaxis over two years while on a combination of pulsed iNO and epoprostenol.[46] In a case report of a patient awaiting heart-lung transplantation, the patient experienced hypotensive bradycardia upon an attempt to wean from iNO therapy. In addition, a recurrence in hypotensive bradycardia resulted in the increase of iNO dose (40–106 ppm), followed by a decrease to 70 ppm (along with administration of bicarbonate and reintroduction of prostacyclin) after increasing metabolic acidosis.[55]

There is evidence that pulsed delivery may allow utilization of lower NO concentrations compared with continuous face mask administration, potentially minimizing the risk of associated adverse events as well as resulting in a more practical delivery system.[49]

The consensus on treatment for PAH encompasses numerous goals, the most important being to improve overall quality of life by decreasing symptoms while minimizing treatment-related side effects.[2] Additional goals include enhancing functional capacity, i.e., exercise capacity, improving hemodynamic derangements (lowering PVR and PAP, and normalizing RAP and CO), and preventing, if not reversing, disease progression. Finally, improving survival, although certainly desirable, is rarely an end point in trials examining PAH treatment.[2] The availability of novel treatments and the improvement in survival rates have allowed the goals of PAH therapy to expand from improving survival and preventing disease progression to also improving HRQOL.[71] Potential advances in long-term PAH treatment, such as ambulatory iNO administration, may allow for greater improvements in HRQOL. Pérez–Peñate et al. observed that ambulatory pulsed iNO treatment did not diminish quality of life beyond the consequences of the disease itself.[47] Eight of eleven patients who led a nonsedentary life were able to leave their home daily, with four returning to work while on long-term iNO therapy.

An ideal drug-device for long-term PAH treatment should emphasize portability and safety features for outpatient use. Advances in iNO gas delivery technology and strategies to optimize dosing should allow for randomized controlled trials of iNO and, hopefully, may lead to broad-scale application of iNO in the treatment of chronic diseases such as PAH.[45]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Michael Morren, RPh, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, for providing medical writing and editorial assistance, which was funded by Ikaria, Inc., during the preparation of this manuscript. No author received an honoraria or other form of financial support for the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Porhownik NR, Bshouty Z. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: A serious problem. Perspect Cardiol. 2007:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119:2250–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badesch DB, Champion HC, Sanchez MA, Hoeper MM, Loyd JE, Manes A, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thenappan T, Shah SJ, Rich S, Tian L, Archer SL, Gomberg-Maitland M. Survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: A reappraisal of the NIH risk stratification equation. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1079–87. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00072709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peacock AJ, Murphy NF, McMurray JJ, Caballero L, Stewart S. An epidemiological study of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:104–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frost AE, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Benza RL, Elliott CG, Farber HW, et al. The changing picture of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in the United States: How REVEAL differs from historic and non-US Contemporary Registries. Chest. 2011;139:128–37. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coghlan JG, Pope J, Denton CP. Assessment of endpoints in pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16(Suppl 1):S27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000370208.45756.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, Torbicki A, Vachiery JL, Barbera JA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2493–537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taichman DB, Shin J, Hud L, Rcher-Chicko C, Kaplan S, Sager JS, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res. 2005;6:92. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galie N, Manes A, Negro L, Palazzini M, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Branzi A. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:394–403. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonneau G, Rubin LJ, Galie N, Barst RJ, Fleming TR, Frost AE, et al. Addition of sildenafil to long-term intravenous epoprostenol therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:521–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-8-200810210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olschewski H, Simonneau G, Galie N, Higenbottam T, Naeije R, Rubin LJ, et al. Inhaled iloprost for severe pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:322–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barst RJ, Rubin LJ, Long WA, McGoon MD, Rich S, Badesch DB, et al. A comparison of continuous intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) with conventional therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension. The Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:296–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman JH, Fanburg BL, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Garcia JG, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: future directions: Report of a National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute/Office of Rare Diseases workshop. Circulation. 2004;109:2947–52. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132476.87231.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dupuis J. Endothelin-receptor antagonists in pulmonary hypertension. Lancet. 2001;358:1113–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGoon MD, Kane GC. Pulmonary hypertension: Diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:191–207. doi: 10.4065/84.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barst RJ, Gibbs JS, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, McLaughlin VV, Rubin LJ, et al. Updated evidence-based treatment algorithm in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.South San Francisco, CA: Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc; 2011. Tracleer [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinhorn RH. Therapeutic approaches using nitric oxide in infants and children. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1027–34. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinton, NJ: INO Therapeutics; 2010. INOmax [package insert] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frostell CG, Blomqvist H, Hedenstierna G, Lundberg J, Zapol WM. Inhaled nitric oxide selectively reverses human hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction without causing systemic vasodilation. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:427–35. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frostell C, Fratacci MD, Wain JC, Jones R, Zapol WM. Inhaled nitric oxide.A selective pulmonary vasodilator reversing hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Circulation. 1991;83:2038–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberger B, Laskin DL, Heck DE, Laskin JD. The toxicology of inhaled nitric oxide. Toxicol Sci. 2001;59:5–16. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/59.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barst RJ, Agnoletti G, Fraisse A, Baldassarre J, Wessel DL for the NO Diagnostic Study Group. Vasodilator testing with nitric oxide and/or oxygen in pediatric pulmonary hypertension. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:598–606. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9645-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elahi MM, Worner M, Khan JS, Matata BM. Inspired nitric oxide and modulation of oxidative stress during cardiac surgery. Curr Drug Saf. 2009;4:188–98. doi: 10.2174/157488609789006958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winterhalter M, Simon A, Fischer S, Rahe-Meyer N, Chamtzidou N, Hecker H, et al. Comparison of inhaled iloprost and nitric oxide in patients with pulmonary hypertension during weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass in cardiac surgery: A prospective randomized trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:406–13. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fattouch K, Sbraga F, Bianco G, Speziale G, Gucciardo M, Sampognaro R, et al. Inhaled prostacyclin, nitric oxide, and nitroprusside in pulmonary hypertension after mitral valve replacement. J Card Surg. 2005;20:171–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0886-0440.2005.200383w.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solina AR, Ginsberg SH, Papp D, Grubb WR, Scholz PM, Pantin EJ, et al. Dose response to nitric oxide in adult cardiac surgery patients. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13:281–6. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(01)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris K, Beghetti M, Petros A, Adatia I, Bohn D. Comparison of hyperventilation and inhaled nitric oxide for pulmonary hypertension after repair of congenital heart disease. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2974–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solina A, Papp D, Ginsberg S, Krause T, Grubb W, Scholz P, et al. A comparison of inhaled nitric oxide and milrinone for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension in adult cardiac surgery patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:12–7. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(00)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westphal K, Martens S, Strouhal U, Matheis G, Hommel K, Kessler P. Nitric oxide inhalation in acute pulmonary hypertension after cardiac surgery reduces oxygen concentration and improves mechanical ventilation but not mortality. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;46:70–3. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadao K, Masahiro S, Toshihiko M, Yasuaki N, Yusaku T. Effect of nitric oxide on oxygenation and hemodynamics in infants after cardiac surgery. Artif Organs. 1997;21:14–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1997.tb00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auler Junior JO, Carmona MJ, Bocchi EA, Bacal F, Fiorelli AI, Stolf NA, et al. Low doses of inhaled nitric oxide in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:443–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner F, Buz S, Neumeyer HH, Hetzer R, Hocher B. Nitric oxide inhalation modulates endothelin-1 plasma concentration gradients following left ventricular assist device implantation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44(Suppl 1):S89–S91. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000166206.74178.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner FD, Buz S, Knosalla C, Hetzer R, Hocher B. Modulation of circulating endothelin-1 and big endothelin by nitric oxide inhalation following left ventricular assist device implantation. Circulation. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II278–II284. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000090630.48893.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macdonald PS, Keogh A, Mundy J, Rogers P, Nicholson A, Harrison G, et al. Adjunctive use of inhaled nitric oxide during implantation of a left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:312–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner F, Dandel M, Gunther G, Loebe M, Schulze-Neick I, Laucke U, et al. Nitric oxide inhalation in the treatment of right ventricular dysfunction following left ventricular assist device implantation. Circulation. 1997;96:II–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inglessis I, Shin JT, Lepore JJ, Palacios IF, Zapol WM, Bloch KD, et al. Hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide in right ventricular myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:793–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreno I, Vicente R, Mir A, Leon I, Ramos F, Vicente JL, et al. Effects of inhaled nitric oxide on primary graft dysfunction in lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2210–2. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Botha P, Jeyakanthan M, Rao JN, Fisher AJ, Prabhu M, Dark JH, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide for modulation of ischemia-reperfusion injury in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:1199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meade MO, Granton JT, Matte-Martyn A, McRae K, Weaver B, Cripps P, et al. A randomized trial of inhaled nitric oxide to prevent ischemia-reperfusion injury after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1483–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2203034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meade M, Granton JT, Matte-Martyn A, McRae K, Cripps PM, Weaver B, et al. A randomized trial of inhaled nitric oxide to prevent reperfusion injury following lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:254–5. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thabut G, Brugiere O, Leseche G, Stern JB, Fradj K, Herve P, et al. Preventive effect of inhaled nitric oxide and pentoxifylline on ischemia/reperfusion injury after lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:1295–300. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200105150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fullerton DA, Eisenach JH, McIntyre RC, Jr, Friese RS, Sheridan BC, Roe GB, et al. Inhaled nitric oxide prevents pulmonary endothelial dysfunction after mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L326–31. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bloch KD, Ichinose F, Roberts JD, Jr, Zapol WM. Inhaled NO as a therapeutic agent. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:339–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ivy DD, Parker D, Doran A, Parker D, Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Acute hemodynamic effects and home therapy using a novel pulsed nasal nitric oxide delivery system in children and young adults with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:886–90. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez-Penate GM, Julia-Serda G, Ojeda-Betancort N, Garcia-Quintana A, Pulido-Duque J, Rodriguez-Perez A, et al. Long-term inhaled nitric oxide plus phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors for severe pulmonary hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Channick RN, Newhart JW, Johnson FW, Williams PJ, Auger WR, Fedullo PF, et al. Pulsed delivery of inhaled nitric oxide to patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: an ambulatory delivery system and initial clinical tests. Chest. 1996;109:1545–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.6.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kitamukai O, Sakuma M, Takahashi T, Nawata J, Ikeda J, Shirato K. Hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide using pulse delivery and continuous delivery systems in pulmonary hypertension. Intern Med. 2002;41:429–34. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.41.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ivy DD, Griebel JL, Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Acute hemodynamic effects of pulsed delivery of low flow nasal nitric oxide in children with pulmonary hypertension. J Pediatr. 1998;133:453–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossaint R, Falke KJ, Lopez F, Slama K, Pison U, Zapol WM. Inhaled nitric oxide for the adult respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:399–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302113280605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cepkova M, Matthay MA. Pharmacotherapy of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 2006;21:119–43. doi: 10.1177/0885066606287045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walmrath D, Schneider T, Pilch J, Grimminger F, Seeger W. Aerosolised prostacyclin in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet. 1993;342:961–2. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92004-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez-Penate G, Julia-Serda G, Pulido-Duque JM, Gorriz-Gomez E, Cabrera-Navarro P. One-year continuous inhaled nitric oxide for primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2001;119:970–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.3.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snell GI, Salamonsen RF, Bergin P, Esmore DS, Khan S, Williams TJ. Inhaled nitric oxide used as a bridge to heart-lung transplantation in a patient with end-stage pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1263–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.4.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heinonen E, Nyman G, Merilainen P, Hogman M. Effect of different pulses of nitric oxide on venous admixture in the anaesthetized horse. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:394–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heinonen E, Merilainen P, Hogman M. Administration of nitric oxide into open lung regions: delivery and monitoring. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:338–42. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heinonen E, Hogman M, Merilainen P. Theoretical and experimental comparison of constant inspired concentration and pulsed delivery in NO therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1116–23. doi: 10.1007/s001340051326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lepore JJ, Maroo A, Bigatello LM, Dec GW, Zapol WM, Bloch KD, et al. Hemodynamic effects of sildenafil in patients with congestive heart failure and pulmonary hypertension: Combined administration with inhaled nitric oxide. Chest. 2005;127:1647–53. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lepore JJ, Maroo A, Pereira NL, Ginns LC, Dec GW, Zapol WM, et al. Effect of sildenafil on the acute pulmonary vasodilator response to inhaled nitric oxide in adults with primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:677–80. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giaid A, Saleh D. Reduced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:214–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507273330403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller OI, Tang SF, Keech A, Celermajer DS. Rebound pulmonary hypertension on withdrawal from inhaled nitric oxide. Lancet. 1995;346:51–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davidson D, Barefield ES, Kattwinkel J, Dudell G, Damask M, Straube R, et al. Safety of withdrawing inhaled nitric oxide therapy in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatrics. 1999;104:231–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ivy DD, Kinsella JP, Ziegler JW, Abman SH. Dipyridamole attenuates rebound pulmonary hypertension after inhaled nitric oxide withdrawal in postoperative congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:875–82. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Atz AM, Wessel DL. Sildenafil ameliorates effects of inhaled nitric oxide withdrawal. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:307–10. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199907000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Raja SG. Treatment of rebound pulmonary hypertension: why not sildenafil? Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1480. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200412000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Namachivayam P, Theilen U, Butt WW, Cooper SM, Penny DJ, Shekerdemian LS. Sildenafil prevents rebound pulmonary hypertension after withdrawal of nitric oxide in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1042–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-694OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee JE, Hillier SC, Knoderer CA. Use of sildenafil to facilitate weaning from inhaled nitric oxide in children with pulmonary hypertension following surgery for congenital heart disease. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23:329–34. doi: 10.1177/0885066608321389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vonbank K, Ziesche R, Higenbottam TW, Stiebellehner L, Petkov V, Schenk P, et al. Controlled prospective randomised trial on the effects on pulmonary haemodynamics of the ambulatory long term use of nitric oxide and oxygen in patients with severe COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:289–93. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mizutani T, Layon AJ. Clinical applications of nitric oxide. Chest. 1996;110:506–24. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen H, De Marco T, Kobashigawa EA, Katz PP, Chang VW, Blanc PD. Comparison of cardiac and pulmonary-specific quality of life measures in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:608–16. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00161410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]