Abstract

Background

Nocebo phenomena are common in clinical practice and have recently become a popular topic of research and discussion among basic scientists, clinicians, and ethicists.

Methods

We selectively searched the PubMed database for articles published up to December 2011 that contained the key words “nocebo” or “nocebo effect.”

Results

By definition, a nocebo effect is the induction of a symptom perceived as negative by sham treatment and/or by the suggestion of negative expectations. A nocebo response is a negative symptom induced by the patient’s own negative expectations and/or by negative suggestions from clinical staff in the absence of any treatment. The underlying mechanisms include learning by Pavlovian conditioning and reaction to expectations induced by verbal information or suggestion. Nocebo responses may come about through unintentional negative suggestion on the part of physicians and nurses. Information about possible complications and negative expectations on the patient’s part increases the likelihood of adverse effects. Adverse events under treatment with medications sometimes come about by a nocebo effect.

Conclusion

Physicians face an ethical dilemma, as they are required not just to inform patients of the potential complications of treatment, but also to minimize the likelihood of these complications, i.e., to avoid inducing them through the potential nocebo effect of thorough patient information. Possible ways out of the dilemma include emphasizing the fact that the proposed treatment is usually well tolerated, or else getting the patient’s permission to inform less than fully about its possible side effects. Communication training in medical school, residency training, and continuing medical education would be desirable so that physicians can better exploit the power of words to patients’ benefit, rather than their detriment.

Words are the most powerful tool a doctor possesses, but words, like a two-edged sword, can maim as well as heal.“, Bernard Lown (e1).

Doctor–patient communication and the patient’s treatment expectations can have considerable consequences, both positive and negative, on the outcome of a course of medical therapy. The positive influence of doctor–patient communication, treatment expectations, and sham treatments, termed placebo effect, has been known for many years (e2) and extensively studied (1). The efficacy of placebo has been demonstrated for subjective symptoms such as pain and nausea (1). The Scientific Advisory Board of the German Medical Association published a statement on placebo in medicine in 2010 (2).

Method

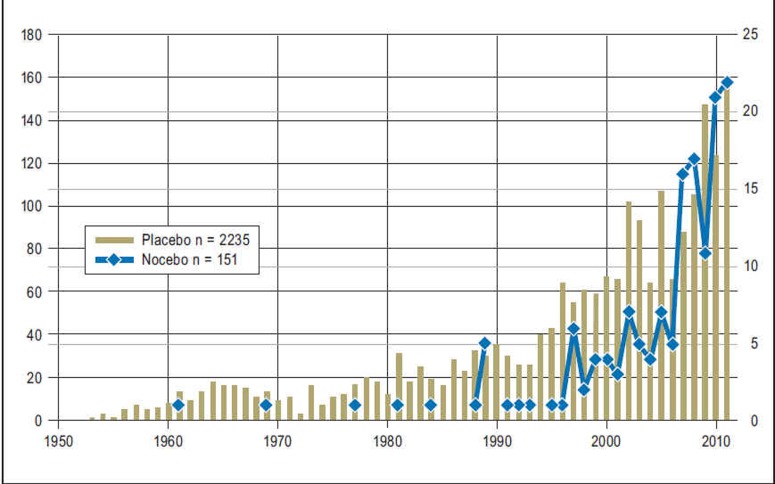

The opposite of the placebo phenomenon, namely nocebo phenomena, have only recently received wider attention from basic scientists and clinicians. A search of the PubMed database on 5 October 2011 revealed 151 publications on the topic of “nocebo,” compared with over 150 000 on “placebo.” Stripping away from the latter all articles in which “only” placebo-controlled drug trials were reported left around 2200 studies investigating current knowledge of the placebo effect. In comparison, the data on the nocebo effect are sparse. Of the 151 publications, only just over 20% were empirical studies: the rest were letters to the editor, commentaries, editorials, and reviews (Figure).

Figure.

Number of studies on the placebo effect (olive-green bars, left ordinate) and the nocebo effect (blue diamonds, right ordinate) in PubMed between 1950 and 2011

Our intention here is to portray the neurobiological mechanisms of nocebo phenomena. Furthermore, in order to sensitize clinicians to the nocebo phenomena in their daily work we present studies on nocebo phenomena in randomized placebo-controlled trials and in clinical practice (medicinal treatment and surgery). Finally, we discuss the ethical problems that arise from nocebo phenomena which may be induced by explanation of the proposed treatment in the course of the patient briefing and describe possible solutions.

Definition of nocebo phenomena

The term “nocebo” was originally coined to give a name to the negative equivalent of placebo phenomena and distinguish between desirable and undesirable effects of placebos (sham medications or other sham interventions, for instance simulated surgery). “Nocebo” was used to describe an inactive substance or ineffective procedure that was designed to arouse negative expectations (e.g., giving sham medication while verbally suggesting an increase in symptoms) (3).

“Placebo” and “nocebo” are meanwhile being used in another sense: The effects of every medical treatment, for example administration of drugs or psychotherapy, are divided into specific and non-specific. Specific effects are caused by the characteristic elements of the intervention. The non-specific effects of a treatment are called placebo effects when they are beneficial and nocebo effects when they are harmful.

Placebo and nocebo effects are seen as psychobiological phenomena that arise from the therapeutic context in its entirety, including sham treatments, the patients’ treatment expectations and previous experience, verbal and non-verbal communications by the person administering the treatment, and the interaction between that person and the patient (4). The term “nocebo effect” covers new or worsening symptoms that occur during sham treatment e.g., in the placebo arm of a clinical trial or as a result of deliberate or unintended suggestion and/or negative expectations. “Nocebo response” is used to mean new and worsening symptoms that are caused only by negative expectations on the part of the patient and/or negative verbal and non-verbal communications on the part of the treating person, without any (sham) treatment (5).

Experimental nocebo research

Experimental nocebo research aims to answer three central questions:

Are nocebo effects caused by the same psychological mechanisms as placebo effects, i.e., by learning (conditioning) and reaction to expectations?

Are placebo and nocebo effects based on the same or different neurobiological events?

Are the predictors of nocebo effects different from those of placebo effects?

Psychological mechanisms

The proven mechanisms of the placebo response include learning by Pavlovian conditioning and reaction to expectations aroused by verbal information or suggestion (6). Learning experiments with healthy probands have shown that worsening of symptoms of nausea (caused by spinning on a swivel chair) can be conditioned (7). Expectation-induced cutaneous hyperalgesia could be produced experimentally through verbal suggestion alone (8). Social learning by observation led to placebo analgesia on the same order as direct experience by conditioning (9).

Nocebo responses can also be demonstrated in patients. In an experimental study, 50 patients with chronic back pain were randomly divided into two groups before a leg flexion test: One group was informed that the test could lead to a slight increase in pain, while the other group was told that the test had no effect on pain level. The group with negative information reported stronger pain (pain intensity 48.1 [standard deviation (SD) 23.7] versus 30.2 [SD 19.6] on a 101-point scale) and performed fewer leg flexions (52.1 [SD 12.5] versus 59.7 [SD 5.9]) than the group with neutral instruction (10).

It can be concluded from these studies that both placebo and nocebo responses can be acquired via all kinds of learning. If such reactions occur in everyday clinical practice, one must assume that they arise from the patient’s expectations or previous learning experiences (5).

Neurobiological correlates

A key part in the mediation of the placebo response is played by a number of central chemical messengers. Especially dopamine and endogenous opiates have been demonstrated to be central mediators of placebo analgesia. These two neurobiological substrates have also been shown to play a part in the nocebo response (hyperalgesia): While secretion of dopamine and endogenous opioids is increased in placebo analgesia, this reaction is decreased in hyperalgesia (11). Because worsening of symptoms e.g., increased sensitivity to pain is often associated with anxiety, other central processes play a part, e.g., the neurohormone cholecystokinin (CCK) in pain (12). To date, a genetic predisposition to placebo response has been demonstrated only for depression and social anxiety (e3); such a predisposition to nocebo response has so far not been shown (e4).

Interindividual variation

Sex is a proven predictor of the placebo response and also exerts some influence on the nocebo response. In the above-mentioned study on the aggravation of symptoms of nausea, women were more susceptible to conditioning and men to generated expectations (6).

Identification of predictors of nocebo responses is a central goal of ongoing investigations. The aim is to pinpoint groups at risk of nocebo responses, for example patients with high levels of anxiety, and optimize the therapeutic context accordingly (13).

Generation of nocebo responses by doctor– patient and nurse–patient communication

The verbal and non-verbal communications of physicians and nursing staff contain numerous unintentional negative suggestions that may trigger a nocebo response (14).

Patients are highly receptive to negative suggestion, particularly in situations perceived as existentially threatening, such as impending surgery, acute severe illness, or an accident. Persons in extreme situations are often in a natural trance state and thus highly suggestible (15, 16). This state of consciousness leaves those affected vulnerable to misunderstandings arising from literal interpretations, ambiguities, and negative suggestion (Box).

Box. Unintended negative suggestion in everyday clinical practice (after 15, e5, e6).

-

Causing uncertainty

“This medication may help.”

“Let’s try this drug.”

“Try to take your meds regularly.”

-

Jargon

“We’re wiring you up now.” (connection to the monitoring device)

“Then we’ll cut you into lots of thin slices.” (computed tomography)

“Now we’re hooking you up to the artificial nose.” (attaching an oxygen mask)

“We looked for metastases—the result was negative.”

-

Ambiguity

“We’ll just finish you off.” (preparation for surgery)

“We’re putting you to sleep now, it’ll soon be all over.” (induction of anesthesia)

“I’ll just fetch something from the ’poison cabinet’ (secure storage for anesthetics), then we can start.”

-

Emphasizing the negative

“You are a high-risk patient.”

“That always hurts a lot.”

“You must strictly avoid lifting heavy objects—you don’t want to end up paralyzed.”

“Your spinal canal is very narrow—the spinal cord is being compressed.”

-

Focusing attention

“Are you feeling nauseous?” (recovery room)

“Signal if you feel pain.” (recovery room)

-

Ineffective negation and trivialization

“You don’t need to worry.”

“It’s just going to bleed a bit.”

In medical practice the assumption is that the patient’s pain and anxiety are minimized when a painful manipulation is announced in advance and any expression of pain by the patient is met with sympathy. A study of patients receiving injections of radiographic substances showed that their anxiety and pain were heightened by the use of negative words such as “sting,” “burn,” “hurt,” “bad,” and “pain” when explaining the procedure or expressing sympathy (17). In another study, injection of local anesthetic preparatory to the induction of epidural anesthesia in women about to give birth was announced by saying either “We are going to give you a local anesthetic that will numb the area so that you will be comfortable during the procedure” or “You are going to feel a big bee sting; this is the worst part of the procedure.” The perceived pain was significantly greater after the latter statement (median pain intensity 5 versus 3 on an 11-point scale) (18).

The patient’s expectations

Just as the announcement that a drug is going to be given can provoke its side effects even if it is not actually administered, telling headache patients that they are going to experience a mild electric current or an electromagnetic field (e.g., from cell phones) produces headaches (e7). The symptoms of Parkinson’s disease patients undergoing deep brain stimulation are more pronounced if they know their brain pacemaker is going to be turned off than if they do not know (e8).

Nocebo phenomena in drug treatment

Researchers distinguish true placebo effects from perceived placebo effects. The true placebo effect is the whole effect in the placebo group minus non-specific factors such as natural disease course, regression to the mean, and unidentified parallel interventions. The true placebo effect can be quantified only by comparing a placebo group and an untreated group (19). The true nocebo effect in double-blind drug trials thus includes all negative effects in placebo groups minus non-specific factors such as symptoms from the treated disease or comorbid conditions and adverse events of accompanying medication (4). The nocebo effects in drug trials referred to below are perceived rather than “true” nocebo effects.

Adverse event profile and discontinuation rates in placebo groups of randomized trials

A systematic review showed that in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of migraine (69 studies in total, 56 of them with triptans, 9 with anticonvulsants, and 8 with non-steroidal antirheumatic drugs), the side effect profile of placebo corresponded with that of the “true” drug being tested (20). A systematic review of RCTs of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs; 21 studies) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; 122 studies) revealed a significantly higher rate of adverse events in both the verum and placebo arms of the TCA trials compared to the verum and placebo arms of the SSRI trials. Patients given TCA placebos were significantly more likely to report dry mouth (19.2% versus 6.4%), vision problems (6.9% versus 1.2%), fatigue (17.3% versus 5.5%), and constipation (10.7% versus 4.2%) than patients taking SSRI placebos (21).

The side effects of medications therefore depend on what adverse events the patients and their treating physicians expect (20, 21). Rates of discontinuation owing to adverse effects of placebo in double-blind trials on patients with various diseases are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Systematic reviews: discontinuation rates in placebo arms of randomized trials owing to adverse events.

| Reference | Verum | Number of studies | Discontinuation rate (%) |

| e9 | Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases: statins | 20 | 4–26* |

| e10 | Multiple sclerosis: immune modulators | 56 | 2.1 (95% CI: 1.6–2.7) |

| e10 | Multiple sclerosis: symptomatic treatment | 44 | 2.4 (95% CI: 1.5–3.3) |

| e11 | Acute treatment of migraine | 59 | 0.3 (95% CI: 0.2–0.5) |

| e11 | Prevention of migraine | 31 | 4.8 (95% CI: 3.3–6.5) |

| e11 | Prevention of tension headache | 4 | 5.4 (95% CI: 1.3–12.1) |

| 22 | Painful peripheral diabetic polyneuropathy | 62 | 5.8 (95% CI: 5.1–6.6) |

| 22 | Fibromyalgia syndrome | 58 | 9.5 (95% CI: 8.6–10.7) |

CI = confidence interval;

*no data on pooled discontinuation rates

Problems in evaluating side effects of drugs

The methods used for recording adverse events influence the type and the frequency of effects reported: Patients specify more adverse events when checking off a standardized list of symptoms than when they report them spontaneously (21). In a large proportion of double-blind drug trials, the way in which subjective drug side effects were recorded is described inadequately or not at all (22). The robustness of the data on which summaries of product characteristics and package inserts are based must therefore be seen in a critical light.

The problems in evaluating side effects of drugs in RCTs also apply in everyday clinical practice. Is the symptom reported by the patient—nausea, for example—a side effect of medication, a symptom of the disease being treated, a symptom of another disease, or a (temporary) indisposition unconnected with either the drug or the disease?

Nocebo effects during drug treatment in everyday clinical practice

Nocebo effects have been described in (Table 2):

Table 2. Nocebo effects in clinical studies.

| Reference | Diagnosis | Number of patients | Results |

| e12 | Case series: exposure test in known drug allergy | 600 | 27% reported adverse events (nausea, stomach pains, itching) on placebo |

| e13 | Case series: exposure test in known drug allergy | 435 | 32% reported adverse events (nausea, stomach pains, itching) on placebo |

| e14 | Two RCTs: fatigue in advanced cancer | 105 | 79% reported sleep problems, 53% loss of appetite, and 33% nausea on placebo* |

| e15 | RCT: perioperative administration of drugs | 360 | Undesired effects were reported by 5–8% of patients in the sodium chloride group, 8% of patients in the midazolam-placebo group, and 3–8% of patients in the fentanyl-placebo group |

| e16 | RCT: finasteride in benign prostate hyperplasia | 107 | Blinded administration of finasteride led to a significantly higher rate of sexual dysfunction (44%) in the group that was informed of this possible effect than in the group that was not informed (15%) |

| e17 | RCT: 50 mg atenolol in coronary heart disease | 96 | Rates of sexual dysfunction: 3% in the group that received information on neither drug nor side effect, 16% in the group that was informed about the drug but not about the possibility of sexual dysfunction, 31% in the group that was told about both the drug and the possible sexual dysfunction |

| e18 | RCT: 100 mg atenolol in coronary heart disease | 114 | Rates of sexual dysfunction: 8% in the group that received information on neither drug nor side effect, 13% in the group that was informed about the drug but not about the possibility of sexual dysfunction, 32% in the group that was told about both the drug and the possible sexual dysfunction |

| e19, e20 | Acetylsalicylic acid versus sulfinpyrazone in unstable angina pectoris | 555 | Inclusion of gastrointestinal side effects in the patient briefing at two of the three study centers led to a six-fold rise in the rate of discontinuation owing to subjective gastrointestinal side effects. The study centers with and without briefing on gastrointestinal side effects showed no difference in the frequency of gastrointestinal bleeding or gastric or duodenal ulcers |

| 23 | Controlled study of lactose intolerance | 126 | 44% of persons with known lactose intolerance and 26% of those without lactose intolerance complained of gastrointestinal symptoms after sham administration of lactose |

| e21 | Case report from RCT of antidepressants | 1 | Severe hypotension requiring volume replacement after swallowing 26 placebo tablets with suicidal intent |

*Worse ratings for sleep, appetite, and fatigue before the study were associated with a higher rate of reported adverse events; RCT = randomized controlled trial

Drug exposure tests in the case of known drug allergy

Perioperative administration of drugs

Finasteride in benign prostate hyperplasia

Beta-blocker treatment of cardiovascular diseases

Symptomatic treatment of fatigue in cancer patients

Lactose intolerance.

The lactose content of tablets varies between 0.03 g and 0.5 g. Small amounts of lactose (up to 10 g) are tolerated by almost all lactose-intolerant individuals. Therefore, complaints of gastrointestinal symptoms by lactose-intolerant patients who have been told by the physician or have found out for themselves that the tablets they are taking contain lactose may represent a nocebo effect (23).

In Germany, the aut idem ruling by which pharmacists may substitute a preparation with identical active ingredients for the product named on the prescription and discount agreements have led to complaints from patients and physicians of poor efficacy or increased adverse effects after switching to generic preparations. A cross-sectional survey conducted on behalf of the German Association of Pain Treatment (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schmerztherapie e.V.) and the German Pain League (Deutsche Schmerzliga e.V.) questioned 600 patients who had been switched to an oxycodone-containing generic preparation. Ninety percent were less satisfied with the analgesic effect, and 61% reported increased pain intensity (German-language source: Überall M: IQUISP Gutachten [Fokusgruppe Oxycodonhaltige WHOIII Opioide] Querschnittsbefragung zu den psychosozialen Folgen einer Umstellung von Originalpräparaten auf Generika bei chronisch schmerzkranken Menschen im Rahmen einer stabilen/zufriedenstellenden Behandlungssituation. Überall M: IQUISP Expert Report [Focus Group Oxycodone-containing WHO III Opioids]: cross-sectional survey on the psychosocial consequences of substituting original preparations with generics for treatment of chronic pain in a stable/satisfactory treatment context [talk held on 8 March 2008 at a symposium sponsored by Mundipharma during the 19th German Interdisciplinary Pain Congress]).

A qualitative systematic review showed that patients with increased anxiety, depressivity, and somatization tendency are at greater risk of adverse events after switching to generic preparations (24). It must be discussed whether critical statements by medical opinion leaders (e22) and representatives of patients’ self-help organizations (e23) on the substitution of powerful opioid preparations by generic equivalents might not be leading to nocebo effects. In the words of one such statement: “The consequences of substitution are always the same: more pain or more adverse events” (e23).

Expectations that a treatment will be poorly tolerated, whether based on experience or induced by information from the media or trusted third parties, may bring about nocebo effects. A systematic review and meta-analysis found a robust association between the expectation and the occurrence of nausea after chemotherapy (e24).

Ethical implications and the dilemma of the patient briefing

On one hand physicians are obliged to inform the patient about the possible adverse events of a proposed treatment so that he/she can make an informed decision (e25). On the other, it is the physician’s duty to minimize the risks of a medical intervention for the patient, including those entailed by the briefing (25). However, the studies just cited show that the patient briefing can induce nocebo responses.

The following strategies are suggested to reduce this dilemma:

Focus on tolerability: Information about the frequency of possible adverse events can be formulated positively (“the great majority of patients tolerate this treatment very well”) or negatively (“5% of patients report…”) (4). A study on briefing in the context of influenza vaccination showed that fewer adverse events were reported after vaccination by the group told what proportion of persons tolerated the procedure well than by those informed what proportion experienced adverse events (e26).

Permitted non-information: Before the prescription of a drug, the patient is asked whether he/she agrees to receive no information about mild and/or transient side effects. The patient must, however, be briefed about severe and/or irreversible side effects (5). “A relatively small proportion of patients who take Drug X experience various side effects that they find bothersome but are not life threatening or severely impairing. Based on research, we know that patients who are told about these sorts of side effects are more likely to experience them than those who are not told. Do you want me to inform you about these side effects or not?” (5).

To respect patients’ autonomy and preferences, they can be given a list of categories of possible adverse events for the medication/procedure in question. Each individual patient can then decide which categories of side effects he/she definitely wants to be briefed about and for which categories information can be dispensed with (e27).

Patient education: A systematic review (four studies, 400 patients) of patients with chronic pain showed that training from a pharmacist—e.g., general information on medicinal and non-medicinal pain treatment or on the recording of possible side effects of drugs and guidance in the case of their occurrence—reduced the number of side effects of medications from 4.6 to 1.6 (95% confidence interval of difference: 0.7–5.3) (e28).

Perspectives

Communication training with actor-patients or role-plays during medical studies or in curricula for psychosomatic basic care impart the ability to harness the “power” of the physician’s utterances selectively for the patient’s benefit (e29, e30). Skill in conveying positive suggestions and avoiding negative ones should also receive more attention in nurse training.

The German Medical Association’s recommendations on patient briefing, published in 1990 (e25), urgently require updating. The points that need to be discussed include, for example, whether it is legitimate to express a right of the patient not to know about complications and side effects of medical procedures and whether this must be respected by the physician. Furthermore, it has to be debated whether some patients might not be left confused and uncertain by their inability to follow the legally mandatory comprehensive information on potential complications of medical treatments that is found, for example, on package inserts or multipage information and consent documents.

Key Messages.

Every medical treatment (e.g., drug administration, psychotherapy) has specific and non-specific effects. Specific effects result from the characteristic elements of the intervention. The beneficial non-specific effects of a treatment are referred to as placebo effects, the harmful ones as nocebo effects.

Placebo and nocebo effects are viewed as psychobiological phenomena that arise from the therapeutic context in its entirety (sham treatments, the patients’ treatment expectations and previous experience, verbal and non-verbal communications by the person administering the treatment, and the interaction between that person and the patient).

Nocebo responses may result from unintended negative suggestion by physicians or nurses.

The frequency of adverse events is increased by briefing patients about the possible complications of treatment and by negative expectations on the part of the patient.

Some of the subjective side effects of drugs can be attributed to nocebo effects.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Häuser has received reimbursement of congress and training course fees and travel costs from Eli Lilly and the Falk Foundation, and lecture fees from Eli Lilly, the Falk Foundation, and Janssen-Cilag.

Prof. Hansen has received research funds from Sorin, Italy.

Prof. Enck declares that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3. CD003974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesärztekammer. Stellungnahme des Wissenschaftlichen Beirats der Bundesärztekammer „Placebo in der Medizin“. www.bundesaerztekammer.de/downloads/StellPlacebo2010.pdf. Last accessed on 09 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy WP. The nocebo reaction. Med World. 1961;95:203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colloca L, Sigaudo M, Benedetti F. The role of learning in nocebo and placebo effects. Pain. 2008;136:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colloca L, Miller FG. The nocebo effect and its relevance for clinical practice. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:598–603. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182294a50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enck P, Benedetti F, Schedlowski M. New insights into the placebo and nocebo responses. Neuron. 2008;59:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klosterhalfen S, Kellermann S, Braun S, Kowalski A, Schrauth M, Zipfel S, Enck P. Gender and the nocebo response following conditioning and expectancy. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benedetti F, Lanotte M, Lopiano L, Colloca L. When words are painful: unraveling the mechanisms of the nocebo effect. Neuroscience. 2007;147:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colloca L, Benedetti F. Placebo analgesia induced by social observational learning. Pain. 2009;144:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfingsten M, Leibing E, Harter W, et al. Fear-avoidance behavior and anticipation of pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Pain Med. 2001;2:259–266. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2001.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatuk CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Placebo and nocebo effects are defined by opposite opioid and dopaminergic responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:220–231. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benedetti F, Amanzio M, Vighetti S, Asteggiano G. The biochemical and neuroendocrine bases of the hyperalgesic nocebo effect. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12014–12022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2947-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsikostas DD. Nocebo in headaches: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2012;12:132–137. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen E, Bejenke C. Negative und positive Suggestionen in der Anästhesie - Ein Beitrag zu einer verbesserten Kommunikation mit ängstlichen Patienten bei Operationen. Anaesthesist. 2010;59:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s00101-010-1679-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bejenke CJ. Suggestive communication: its wide applicability in somatic medicine. In: Varga K, editor. Beyond the words: communication and suggestion in medical practice. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2011. pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheek D. Importance of recognizing that surgical patients behave as though hypnotized. Am J ClinHypnosis. 1962;4:227–231. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1962.10401905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang EV, Benotsch EG, Fick LJ, et al. Adjunctive non-pharmacological analgesia for invasive medical procedures: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1486–1490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varelmann D, Pancaro C, Cappiello EC, Camann WR. Nocebo-induced hyperalgesia during local anesthetic injection. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:868–870. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181cc5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst E, Resch KL. Concept of true and perceived placebo effects. BMJ. 1995;311:551–553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7004.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amanzio M, Corazzini LL, Vase L. A systematic review of adverse events in placebo groups of anti-migraine clinical trials. Pain. 2009;146:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rief W, Nestoriuc Y, von Lilienfeld-Toal A, et al. Differences in adverse effect reporting in placebo groups in SSRI and tricyclic antidepressant trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2009;32:1041–1056. doi: 10.2165/11316580-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Häuser W, Bartram C, Bartram-Wunn E, Tölle T. Systematic review: Adverse events attributable to nocebo in randomised controlled drug trials in fibromyalgia syndrome and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:437–451. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182321ad8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vernia P, Di Camillo M, Foglietta T. Diagnosis of lactose intolerance and the „nocebo“ effect: the role of negative expectations. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissenfeld J, Stock S, Lüngen M, Gerber A. The nocebo effect: a reason for patients’ non-adherence to generic substitution? Pharmazie. 2010;65:451–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller FG, Colloca L. The placebo phenomenon and medical ethics: rethinking the relationship between informed consent and risk-benefit assessment. Theor Med Bioeth. 2011;32:229–243. doi: 10.1007/s11017-011-9179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Lown B. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 2004. Die verlorene Kunst des Heilens. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Beecher HK. The powerful placebo. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;159:1602–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960340022006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Furmark T, Appel L, Henningsson S, et al. A link between serotonin-related gene polymorphisms, amygdala activity, and placebo-induced relief from social anxiety. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13066–13074. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2534-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Deykin A, et al. Do „placebo responders“ exist? Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Hansen E, Zimmermann M, Dünzl G. Hypnotische Kommunikation mit Notfallpatienten. Notfall Rettungsmed. 2010;13:314–321. [Google Scholar]

- e6.Hansen E. Negativsuggestionen in der Medizin. Z Hypnose Hypnother. 2011;6:65–82. [Google Scholar]

- e7.Stovner LJ, Oftedal G, Straume A, Johnsson A. Nocebo as headache trigger: evidence from a sham-controlled provocation study with RF fields. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008 188;(Suppl 67) doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Mercado R, Constantoyannis C, Mandat T, Kumar A. Expectation and the placebo effect in Parkinson`s disease patients with subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. Movement Disorders. 2006;21:1457–11461. doi: 10.1002/mds.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Rief W, Avorn J, Barsky AJ. Medication-attributed adverse effects in placebo groups: implications for assessment of adverse effects. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:155–160. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Papadopoulos D, Mitsikostas DD. Nocebo effects in multiple sclerosis trials: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2010;16:816–828. doi: 10.1177/1352458510370793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Mitsikostas DD, Mantonakis LI, Chalarakis NG. Nocebo is the enemy, not placebo. A meta-analysis of reported side effects after placebo treatment in headaches. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:550–561. doi: 10.1177/0333102410391485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Liccardi G, Senna G, Russo M, et al. Evaluation of the nocebo effect during oral challenge in patients with adverse drug reactions. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14:104–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Lombardi C, Gargioni S, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. The nocebo effect during oral challenge in subjects with adverse drug reactions. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;40:138–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.de la Cruz M, Hui D, Parsons HA, Bruera E. Placebo and nocebo effects in randomized double-blind clinical trials of agents for the therapy for fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:766–774. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Manchikanti L, Pampati VKim Damron K. The role of placebo and nocebo effects of perioperative administration of sedatives and opioids in interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2005;8:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Mondaini N, Gontero P, Giubilei G, et al. Finasteride 5 mg and sexual side effects: how many of these are related to a nocebo phenomenon? J Sex Med. 2007;4:1708–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Silvestri A, Galetta P, Cerquetani E, et al. Report of erectile dysfunction after therapy with beta-blockers is related to patient knowledge of side effects and is reversed by placebo. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1928–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Cocco G. Erectile dysfunction after therapy with metoprolol: the Hawthorne effect. Cardiology. 2009;112:174–177. doi: 10.1159/000147951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Cairns JA, Gent M, Singer J, et al. Aspirin, sulfinpyrazone, or both in unstable angina. Results of a Canadian multicenter trial. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1369–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511283132201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Myers MG, Cairns JA, Singer J. The consent form as a possible cause of side effects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987;42:250–253. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1987.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Reeves RR, Ladner ME, Hart RH, Burke RS. Nocebo effects with antidepressant clinical drug trial placebos. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Resolution des Deutschen Schmerztages 2008. Sparmaßnahmen im Gesundheitswesen verletzen Grundrecht auf Leben und körperliche Unversehrtheit. www.schmerz-therapie-deutschland.de/pages/presse/2008/2008_03_08_PM_12_Resolution.pdf. Last accessed on 18 September 2011.

- e23.Koch M. Petitionsausschuss Deutscher Bundestag 95.2011. www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2011/34316512_kw19_pa_petitionen/index.html. Last accessed on 18 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- e24.Colagiuri B, Zachariae R. Patient expectancy and post-chemotherapy nausea: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:3–14. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Bundesärztekammer. Empfehlungen zur Patientenaufklärung. Dtsch Arztebl. 1990;87(16):807–808. [Google Scholar]

- e26.O’Connor AM, Pennie RA, Dales RE. Framing effects on expectations, decisions, and side effects experienced: the case of influenza immunization. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Dworkin G. Cambridge: UK Cambridge University Press; 1988. The Theory and Practice of Autonomy. [Google Scholar]

- e28.Bennett MI, Bagnall AM, Raine G, et al. Educational interventions by pharmacists to patients with chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:623–630. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31821b6be4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Bosse HM, Schultz JH, Nickel M, et al. The effect of using standardized patients or peer role play on ratings of undergraduate communication training: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.007. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Bosse HM, Nickel M, Huwendiek S, Jünger J, Schultz JH, Nikendei C. Peer role-play and standardised patients in communication training: a comparative study on the student perspective on acceptability, realism, and perceived effect. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]