Abstract

Life-threatening fungal infections have increased in recent years while treatment options remain limited. The development of vaccines against fungal pathogens represents a key advance sorely needed to combat the increasing fungal disease threat. Dendritic cells (DC) are uniquely able to shape anti-fungal immunity by initiating and modulating naive T cell responses. Targeting DC may allow for the generation of potent vaccines against fungal pathogens. In the context of anti-fungal vaccine design, we describe the characteristics of the varied DC subsets, how DC recognize fungi, their function in immunity against fungal pathogens, and how DC can be targeted in order to create new anti-fungal vaccines. Ongoing studies continue to highlight the critical role of DC in anti-fungal immunity and will help guide DC-based vaccine strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Fungal pathogens are a serious emerging infectious disease threat and are the target of efforts to develop novel vaccines. The rising danger of mycoses is compounded by both the paucity and toxicity of the pharmacological armamentarium available to treat these infections and the immunocompromised status of the large majority of patients with fungal infections. While fungi are commonly encountered by humans in their environment, particularly as inhaled spores or conidia, few fungal species are human pathogens. Fungi also exist as useful commensal organisms until the host becomes immunodeficient or a systemic portal like a venous catheter is colonized whereupon commensal fungi can cause life threatening infections. Thus, the development of fungal vaccines faces the dual challenge of providing protection to immunocompromised patients and protection against primary pathogens that cause lethal infections in healthy individuals.

The rising incidence of fungal infections is linked to the increase in immunocompromised individuals, specifically, patients with AIDS, patients with cancer, and recipients of solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Candida species are the second leading cause of infectious disease related death in premature infants and the fourth leading cause of hospital bloodstream infections (Benjamin et al., 2010; Pfaller and Diekema, 2007). A rise in the incidence of zygomycosis is also noted in patients with diabetes mellitus (Bitar et al., 2009) augmenting clinical challenges in this growing patient population. Major endemic mycoses can lead to lethal systemic infections in apparently healthy individuals and can reactivate in the setting of immune suppression. Also, fungal-associated allergy and asthma contribute significantly to the human health burden due to fungi.

Encounters with fungi require a coordinated host innate and adaptive immune response to successfully eradicate the fungus and to promote long-lived immunological memory of the encounter. Iatrogenic risk factors for fungal infections such as granulocytopenia, compromised mucosal barriers, and T cell suppressing drugs demonstrate important roles for both innate and adaptive responses to fungi. In fungal infections, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells participate in the elimination of the pathogen (Cutler et al., 2007). Most fungi also elicit antibodies, some of which are protective and can neutralize fungal pathogens or promote fungal uptake by phagocytes (see accompanying review by Casadevall and Pirofski). Phagocytes and other innate immune cells play a critical role in combating fungal pathogens (reviewed by Brown, 2011). Activated phagocytes and neutrophils kill fungi either following phagocytosis or via the production of fungicidal chemicals including reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Epithelial cells also produce fungicidal compounds such as β-defensin and provide a mechanical barrier at mucosal sites exposed to fungi. Expectedly, genetic or acquired deficiency in either the innate or adaptive immune response significantly increases the risk of fungal infection. For example, individuals with an early stop codon mutation in Dectin-1 suffer recurrent mucocutaneous fungal infections (Ferwerda et al., 2009) whereas Pneumocystis pneumonia is a frequent AIDS-defining diagnosis (Huang et al., 2011).

At the intersection of innate and adaptive immunity are dendritic cells (DC), unique cells capable of taking up and processing antigen for presentation by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or MHCII molecules to naive T cells and also themselves possessing potent fungicidal activity. DC recognize fungi via a broad array of surface and intracellular pattern recognition receptors (PRR). Recognition of fungi results in the secretion of cytokines by DC and the expression of co-stimulatory molecules on the DC surface both of which are required to drive naive CD4+ T cell differentiation into a T-helper (Th) phenotype. Clearance of fungi with limited damage to the host requires a finely tuned balance between Th1, Th17, and Treg subsets; the precise response needed is based on the anatomical location and the specific fungal pathogen. DC calibrate and orchestrate the balance of helper, regulatory and effector T-cell responses thus integrating innate and adaptive immune responses to fungi.

The unique ability of DC to initiate and engage anti-fungal immunity positions them as logical cellular targets for the development of fungal vaccines. In this review, we describe the panoply of DC subsets and their function in anti-fungal immunity, identify how DC recognize fungi, and discuss strategies to target DC in the development of novel anti-fungal vaccines. We emphasize DC subsets using murine surface markers; corresponding human DC subset markers continue to be elucidated and are reviewed elsewhere (Naik, 2008).

CHARACTERIZATION AND FUNCTION OF DC AND MONOCYTE SUBSETS

Four decades ago, Steinman and Cohn reported the identification of a cell with “continually elongating, retracting, and reorienting” long cytoplasmic processes in the spleen and lymph nodes of mice (Steinman and Cohn, 1973). These cells, now known as DC, are hematopoietic cells that function as professional antigen presenting cells and that are capable of initiating a T cell response. When DC encounter antigen at the boundary of immunological defense sites such as the skin or the airways of the lung, or in the draining nodes of the lymphatic system, DC amplify the innate immune response by secreting cytokines that recruit and activate other leukocytes. Following engulfment, processing, and presentation of the antigen, DC initiate and shape adaptive response by promoting naïve T cell differentiation into effector or regulatory T cells. Since their discovery, a plethora of DC subsets characterized by anatomical location, function, and surface marker expression have been described (Fig. 1). Indeed, it is the specialized functions of the diverse DC subsets that augment the challenge of targeting DC in the development of anti-fungal vaccines. Therefore, ongoing efforts to characterize the function of DC subsets will enhance the rational design of DC-targeted anti-fungal vaccines.

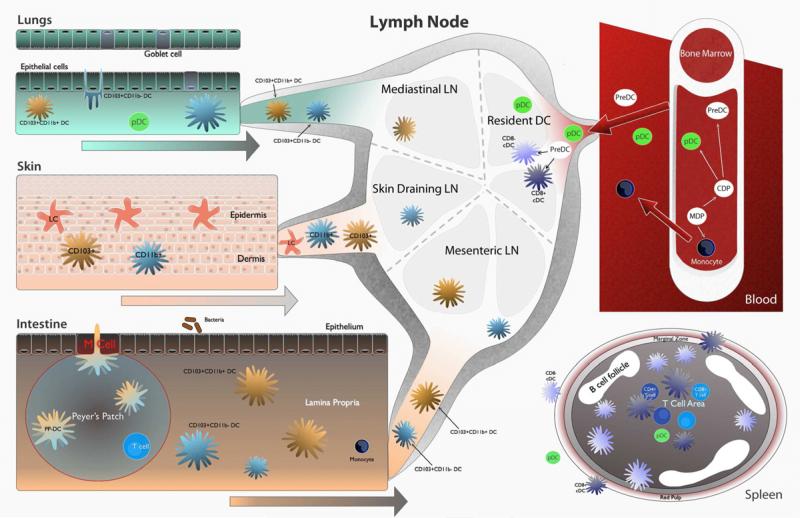

Figure 1. Location of DC subsets important in anti-fungal immunity.

DC subsets and monocytes arise from a common precursor in the bone marrow. pDC, monocytes, and PreDC exit the bone marrow and circulate via the blood. Resident CD8+ and CD8- DC exist in the spleen and the lymph node. PreDC seed the lungs, skin, and intestine and give rise to DC subsets in those locations. Migratory DC subsets migrate from peripheral locations to draining lymph nodes where they interact and prime T cells. In the lungs, CD103+ DC sample antigen from the airway lumen via paracellular processes. CD11b+ DC and CD103+ DC migrate to mediastinal lymph nodes. The epidermis of the skin contains a unique DC subset, Langerhans cells (LC) that are seeded in utero and self-renew. LC sample antigen and migrate via the dermis to skin draining lymph nodes. Dermal DC also migrate to skin draining lymph nodes. In the intestine, DC exist in the Peyer's Patch (PP) and the lamina propria (LP). PP-DC sample antigen using transcellular processes from the intestinal lumen following which they migrate to the T cell rich area of the PP where PP-DC prime T cells. LP-DC subsets migrate to the mesenteric lymph node following antigen sampling. During inflammation, monocytes enter inflamed tissue and differentiate into monocyte-derived DC (Mo-DC) which then carry antigen to draining lymph nodes.

In the steady state, monocytes and DC share a common progenitor cell in the bone marrow, the macrophage-dendritic cell progenitor (MDP) (Fogg et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2009). From the MDP, a common-DC progenitor and monocytes are produced. The common-DC progenitor (CDC), which is restricted to the bone marrow gives rise to three broad groupings of DC: plasmacytoid DC (pDC), conventional DC, and migratory DC. While monocytes and pDC mature in the bone marrow and are released into the blood for circulation to lymphoid tissues, resident and migratory DC precursors known as preDC exit the bone marrow and circulate via the blood before either entering the high endothelial venules of lymphoid tissues or seeding peripheral tissues.

Plasmacytoid DC

pDC are typified by their high production of interferon-α (IFN-α) in response to the sensing of nucleic acids by endosomal Toll-like receptors and are further characterized in part by the high surface expression of sialic acid binding immunoglobulin-like lectin H (Siglec H). Using a Siglec H-DTR depleter mouse, a recent study further elucidated the roles of pDC in vivo (Takagi et al., 2011). Besides nucleic acid sensing, pDC induced IL-10 producing CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, limited Th1 and Th17 cell polarization at mucosal sites, and activated CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, pDC controlled viral infection via the induction of CD8+ T cells, but impaired bacterial clearance and contributed to septic shock. While pDC carry out a well-characterized role in anti-viral immunity, the role of pDC in fungal infections is less clear. pDC recognize Aspergillus fumigatus DNA via TLR9 and are linked with resistance to A. fumigatus infection in mice (Ramirez-Ortiz et al., 2011). Moreover, pDC inhibited fungal growth in vitro and accumulated in the lungs in a murine model of Aspergillus pulmonary infection, suggesting that pDC may recognize and combat fungi directly in vivo. A second subset of pDC exists that develops in the context of elevated IFN-α and is similar to pDC found in Peyer's patches of the gut (Li et al., 2011). Uncharacteristically, this pDC subset fails to produce IFN-α after stimulation with TLR ligands; however, this pDC subset secreted elevated levels of IL-6 and IL-23 and primed robust antigen specific Th17 cells in vivo. This suggests a potential role for IFN-α elicited pDC in the polarization of anti-fungal Th17 cells. Combined with the recent findings that pDC are critical mediators of Treg / Th17 balance at mucosal surfaces, recognition of fungi by pDC or IFN-α elicited pDC at mucosal surfaces may tilt the balance toward tolerance or inflammation.

Conventional DC

Conventional DC, also known as resident DC, exist in the lymphoid tissue and are comprised of two major subpopulations, CD8+ and CD4+CD8- resident DC. In addition, the spleen contains a third minor population of so-called double-negative DC, which lack CD4 and CD8 surface expression and appear to be largely similar in function to CD4+CD8- DC (Luber et al., 2010). CD8+ resident DC are identified by the surface phenotype CD8+CD4-CD11b-CD11c+MHCII+DEC205+ and are located primarily in the T cell zone of the spleen and lymph nodes (Idoyaga et al., 2009). A major function of CD8+ DC is the cross-presentation of antigens via MHCI to CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) (den Haan et al., 2000). CD8+ DC obtain antigen via the engulfment of live or apoptotic cells or antigen containing apoptotic vesicles. CD4+CD8- resident DC are identified by the surface phenotype CD8-CD4+CD11b+CD11c+MHCII+33D1+ and are present in the red pulp and bridging channels of the spleen and the marginal zones and high endothelial venules of the lymph nodes (Liu and Nussenzweig, 2010). In contrast to CD8+ DC, CD4+CD8- DC are not efficient at presenting antigens via MHCI and instead present antigen via MHCII (Dudziak et al., 2007).

Relative to other pathogen classes such as viruses, information regarding the role of resident DC in priming T cell responses to fungi is limited. Direct evidence that resident DC prime anti-fungal T cell responses was demonstrated in a vaccine model to generate immunity to Blastomyces dermatitidis. Lymph node resident DC acquired and displayed antigen and primed antigen specific CD4+ T cells, however acquisition of the antigen depended on ferrying of the yeast from the skin to the lymph node by migratory and monocyte derived DC (Ersland et al., 2010). Less is known about cross-presentation of fungal antigens in vivo. Bone marrow derived DC acquire and cross-present Histoplasma capsulatum antigens to CTL via ingestion of live or killed Histoplasma capsulatum yeasts or via engulfment of Histoplasma containing apoptotic macrophages (Lin et al., 2005). Subcutaneous injection of apoptotic phagocytes containing CFSE labeled heat-killed Histoplasma results in the accumulation of CFSE in CD11c+ cells in skin draining lymph nodes and CD11c+-dependent CTL-mediated protection against Histoplasma challenge (Hsieh et al., 2011). While these studies provide evidence that fungal antigens can be acquired and presented by resident DC, the precise resident DC subpopulation or subpopulations involved in vivo remain undefined. Unexpectedly, CD4+CD8- resident DC may be important for the cross-presentation of fungal antigens. In experiments using an OVA-expressing strain of the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, both CD8+ and CD4+CD8- DC isolated from mouse spleen and primed with OVA-S. cerevisiae induced robust OVA-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation ex vivo however only CD4+CD8- DC stimulated an OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response (Backer et al., 2008). To that end, further studies will be needed to unravel the specific contributions of resident DC subpopulations to CD4+ T cell and CTL activation and polarization in vivo.

Migratory DC

Migratory DC, also referred to as tissue DC, are immature DC that are located principally in peripheral tissues such as the skin, the lung, and the gut. Following uptake of antigen, migratory DC exit the tissue and undergo maturation characterized by (1) enhanced antigen processing and presentation, (2) downregulation of tissue homing receptors, (3) upregulation of CCR7 and (4) increased surface expression of co-stimulatory molecules. CCR7+ DC migrate to the T cell zone of lymphoid tissue where they can initiate activation of naive T cells or transfer antigen to resident DC (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998; Allan et al., 2006). With the exception of Langerhans cells in the epidermis, the majority of migratory DC appear to derive from the same circulating precursor as conventional DC, the preDC. Migratory DC have some capacity for division and self-renewal in situ, while monocyte subsets also contribute to replenishment of migratory DC in certain circumstances. Migratory DC line the surfaces of the body that are exposed to the environment and, as such, are likely to encounter fungi along with other pathogens and antigens. While the migratory DC networks that line the skin, lung, and intestine share similarities, each site has functional differences that are important in anti-fungal immunity and deserve individual discussion.

Skin

The skin is lined by a dense network of DC which can be broadly divided into the epidermis associated Langerhans cell (LC) and a collection of dermis associated dermal DC (Henri et al., 2010a). LC are unique among migratory DC as they arise from a MDP-like cell seeded into the epidermis in utero followed by a wave of expansion within days of birth (Chorro et al., 2009). In addition to their epidermal location, LC are characterized by surface expression of the eponymous langerin (CD207), CD11c, and MHCII. The dermis contains LC that migrate to the draining lymph node, CD207+CD103+ dermal DC, and a diverse group of CD207-CD103- DC (Henri et al., 2010b). Upon subcutaneous administration of a B. dermatitidis vaccine, DEC205 expressing skin-derived DC migrated to the skin draining lymph node in a CCR7-dependent fashion, presented the model antigen expressed by the fungus, and activated CD4+ T cells (Ersland et al., 2010).

Specialized antigen presentation and T cell polarization functions for skin-associated DC subsets – specifically LC, CD207+ dermal DC, and CD207- dermal DC – were elegantly assessed in a cutaneous epidermal exposure model to Candida albicans (Igyarto et al., 2011). LC were necessary and sufficient for the generation of antigen-specific Th17 cells via the production of elevated levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-23, cytokines which promote and stabilize Th17 development. In contrast, LC were not necessary for the generation of CTL. CD207+ dermal DC were required for CTL and also Th1 polarization. Compared with LC, CD207+ dermal DC produced higher levels of IL-12 and IL-27, and lower levels of IL-1β and IL-6, and no IL-23, making them poor promoters of Th17. Moreover, the CD207+ dermal DC inhibited the ability of LC and CD207- dermal DC to promote Th17 responses. Since IL-12 and IL-27, as well as IFN-γ from Th1 cells, inhibit Th17 differentiation and proliferation, CD207+ dermal DC likely block Candida-specific Th17 cells by promoting Th1 differentiation. Thus, exposure of LC and CD207+ dermal DC to Candida can promote opposing effects, through the elaboration of polarizing cytokines that enable the development of Th1 or Th17 responses. Importantly, this study identified a subset of DC that, when targeted, skews differentiation toward Th17 cells, which are instrumental in anti-fungal immunity (Ersland et al., 2010; Igyarto et al., 2011, also see the accompanying review by Hernández-Santos and Gaffen).

Lung

DC in the lung and conducting airways deal with constant exposure to inhaled fungal spores and hyphal fragments. Dense network of DC line the airways, sampling inhaled antigen for subsequent shuttling to mediastinal lymph nodes. Indeed, the airway is currently a target for intranasally delivered vaccine against influenza and may represent a candidate vaccine site against inhaled fungi. Besides pDC, lung DC subsets include two broad divisions: CD103+DC and CD11b+ DC. CD103+ lung DC also express CD207 making them similar to CD207+CD103+ dermal DC in the skin. CD103+DC express tight junction proteins, which allow the DC to intimately associate with airway epithelial cells and to extend dendrites into the airway lumen to sample antigen without disturbing the epithelial barrier (Sung et al., 2006; Jahnsen et al., 2006). Steady state migration of CD103+ DC and CD11b+ DC in the absence of inflammation is responsible for the induction of tolerance to inhaled antigen. CD103+ DC can acquire both soluble and apoptotic cell associated antigens from the airway following which CD103+ DC migrate to the mediastinal lymph node under both steady state and inflammatory conditions. In the mediastinal lymph node CD103+ DC cross-present antigen to and activate CTL (Desch et al., 2011). CD11b+ DC differ from monocyte derived DC and specialize in cytokine and chemokine production (Beaty et al., 2007) as well as presenting antigen via MHCII to CD4+ T cells in the mediastinal lymph node following migration (del Rio et al., 2007). Rapid recruitment of Ly6C+ monocyte derived DC to the lung upon inflammation clouds analysis of the function of lung CD11b+ DC which lack Ly6C+ surface expression. Upon pulmonary exposure to A. fumigatus conidia, CD103+ DC failed to take up and transport conidia to the mediastinal lymph node, whereas CD11b+ DC did transport them (Hohl et al., 2009). In this model, lung CD11b+ DC were reduced relative to wild type mice in CCR2-/- mice following A. fumigatus exposure. Conversely, naive CCR2-/- mice had similar lung CD11b+ DC numbers to wild type mice suggesting that recruited monocyte-derived DC (discussed in detail later in this review) and not lung CD11b+ DC are responsible for conidial uptake and antigen presentation in the setting of A. fumigatus induced inflammation.

Intestine

Just like the lung, DC in the intestine are situated on the basolateral side of the epithelial layer largely isolated from the gut microflora. DC in the intestine localize to two major sub-epithelial locations, the lamina propria and the Peyer's patch; both subsets in each region differentially regulate immune responses. The Peyer's patch is a specialized structure that consists of organized T and B cell follicles capped by a unique epithelial cell dome called an M cell. Peyer's patch DC (PP-DC) extend dendrites through M cells to sample antigen from the intestinal lumen. This transcellular method of antigen sampling appears to be distinct from the paracellular sampling that occurs in the lung and outside of the PP in the intestine (Lelouard et al., 2011). Following antigen internalization, PP-DC migrate to the T cell rich zone of the PP to prime naive T cells.

Lamina propria DC (LP-DC) express CD11c, MHCII, and CD103 and can be further divided into CD11b+ and CD11b- subsets. CD11b+ and CD11b- LP-DC subsets represent two sides of an equilibrium that maintain the balance between the induction of Th17 and Treg responses, respectively, in the intestinal wall (Denning et al., 2011). Indeed, CD11b+ LP-DC numbers are elevated in the duodenum and gradually decrease throughout the small intestine and reach their lowest levels in the colon, mirroring the distribution of Th17 cells. LP-DC play distinct roles in directing CD4+ T cell differentiation in the lamina propria dependent on the local LP-DC to T cell ratio and DC-T cell location along the intestine. Furthermore, the gut microbiota plays a key role in shaping the function of these subsets as LP-DC from mice obtained from separate vendors display strikingly different efficiencies at priming Th17 cells based in part on the presence or absence of segmented filamentous bacteria (Sczesnak et al., 2011). In addition to their ability to affect T cell responses locally in the intestine, both subsets of LP-DC migrate to draining mesenteric lymph nodes where they can further prime and activate T cells.

The role of PP-DC and LP-DC in generating anti-fungal immunity in the gut is unclear and relatively unstudied. C. albicans, a gut commensal fungus, can cause systemic infection if the gut epithelial/DC barrier is substantially breached and/or in the setting of broad-spectrum antibiotic use leading to Candida overgrowth. Strong induction of Treg cells by LP-DC in the mesenteric lymph node may highlight the critical role of limiting inflammation in the gut in order to maintain the epithelial barrier and prevent disseminated infection. Furthermore, heightened Th17 responses in the gut impair protective Th1 responses and worsen Candida infection (Zelante et al., 2007). While bone marrow derived DC produced IL-23 in response to Candida in vitro and IL-23 neutralization promoted fungal clearance in vivo, the identity of the DC subset recognizing and responding to the fungus in this model was not determined. Nevertheless, DC in the gut appear to tightly control tolerance and immunity to fungal organisms.

Monocytes, monocyte derived DC, and inflammatory DC

Monocytes are derived from the MDP and, in the absence of inflammation, are found in the bone marrow and circulating at low levels in the blood and spleen. Two classes of CD11b+CD115+ monocytes arise from the MDP and circulate in the blood, Ly6C+CCR2+ and Ly6C-CX3CR1hi monocytes (Geissmann et al., 2003). Monocytes have broad developmental plasticity and can replenish certain subsets of DC and LC in the setting of experimental depletion (Ginhoux et al., 2007) and thus may represent an emergency store of DC precursors that can be rapidly deployed. Under inflammatory conditions Ly6C+CCR2+ monocytes migrate to the site of inflammation and acquire surface expression of the DC markers CD11c and MHCII while losing Ly6C (Osterholzer et al., 2009) thus becoming “inflammatory DC”. While Ly6C-CX3CR1hi appear not be directly involved in innate immunity to fungi (Dominguez and Ardavin, 2010), Ly6C+CCR2+ monocytes play a critical role responding to many medically relevant fungi such as A. fumigatus (Hohl et al., 2009), Cryptococcus neoformans (Osterholzer et al., 2009), and B. dermatitidis (Ersland et al., 2010).

Compared with any other DC subset, monocyte-derived DCs seem to have an outsized role in anti-fungal immunity, particularly through the induction of Th1 cells. Using CCR2-/- mice (where monocytes are trapped in the bone marrow), inflammatory DC were found to have a critical role in driving a Th1 response and presenting Histoplasma antigen to CD4+ T-cells (Szymczak and Deepe, 2010). CCR2-/- mice also exhibit skewed Th2 responses in H. capsulatum infection and dramatically greater fungal burden in the lung compared to wild-type (WT) animals (Szymczak and Deepe, 2009). Similar CCR2-dependent phenotypes are found in experimental pulmonary infection with A. fumigatus or C. neoformans: priming of Th1 cells in response to fungi critically depends on CCR2+ monocyte derived inflammatory DC (Osterholzer et al., 2009; Hohl et al., 2009). To highlight the importance of the tissue environment in DC function, the defect in CD4+ T cell priming by inflammatory DC during respiratory infection with A. fumigatus is restricted to the lung in CCR2-/- mice and not other lymphoid organs such as the spleen (Hohl et al., 2009). Similarly, while Ly6C+CCR2+ monocytes play a prominent role in delivering B. dermatitidis yeast into skin draining lymph nodes after subcutaneous vaccine delivery, this shuttling function can be compensated in CCR2-/- mice by other skin migratory DC populations (Ersland et al., 2010). Thus, in the setting of the lung, which is the primary route of infection for fungi, but not the skin or the spleen, monocyte-derived DC appear to play a critical role in anti-fungal immunity.

FUNGAL RECOGNITION BY DC

Recognition of fungi by DC is accomplished by a diverse group of PRR that recognize conserved fungal PAMP including proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids (Fig. 2). Anti-fungal immunity depends critically on the recognition of fungi by PRR. Fungal recognition by PPR induces intracellular signaling pathways that lead to DC maturation and secretion of cytokines that instruct the evolving immune response. PRR can also mediate the uptake of fungi by DC and can direct fungi to appropriate intracellular compartments for antigen processing and subsequent presentation. PRR important for the recognition of fungi include Toll-like receptors (TLR) and C-type lectin receptors (CLR), which can respond individually or synergistically to fungi. Other fungal PRR include scavenger receptors such as SCARF1 and CD36 that can mediate binding to C. neoformans (Means et al., 2009) and complement/Fc receptors, which recognize complement factor or antibody coated fungi directly (Taborda and Casadevall, 2002) and mediate phagocytosis.

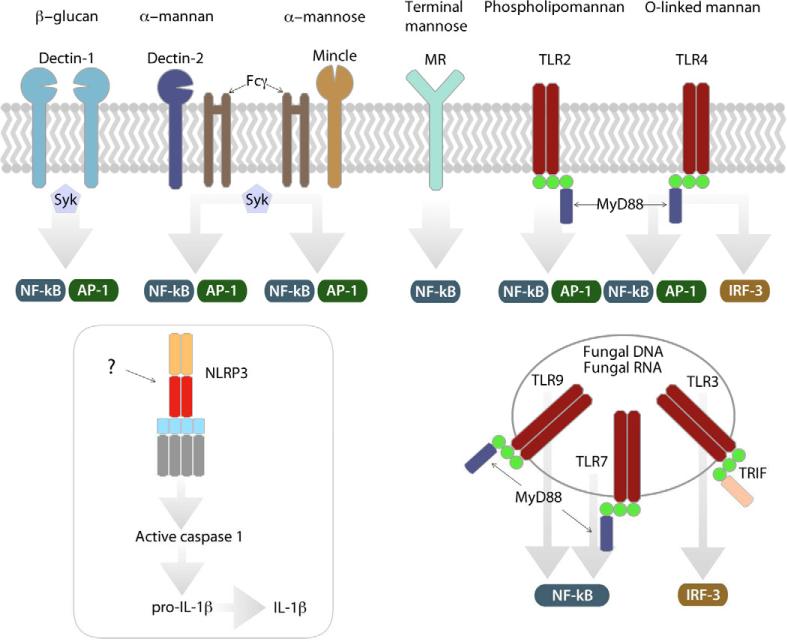

Figure 2. Recognition of fungi via DC PRR.

TLR and CLR. Fungal PAMP are recognized by several PRR: Dectin-1 signals via the tyrosine kinase Syk following recognition of β–glucan. Dectin-2 and Mincle, which also signal via Syk following recruitment of Fcγ, recognize alpha-mannan and alpha mannose respectively. Signaling downstream of the mannose receptor (MR) is undefined. TLR and CLR signaling results in downstream activation of the transcription factors NF-κB or AP-1. Some TLR signaling activates IRF3. While fungi activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, the mechanism is undefined. TLR recognize fungal carbohydrates, fungal DNA, and fungal RNA at the DC surface or in endosomal compartments.

TLR

Recognition of PAMP by TLR results in engagement of intracellular signaling pathways culminating in the activation of the transcription factors activator protein-1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). All TLR transmit their PAMP recognition event via TIR-mediated engagement of myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) with the exception of TLR3, which recruits the adaptor TIR-domain containing adaptor-inducing IFN-beta (TRIF). A subset of TLR are also able to activate interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) or IRF7 which regulate the expression of type I IFN. Since MyD88 is instrumental in priming Th1 cells in response to fungi (Rivera et al., 2006), it is generally thought that fungal recognition by TLR induce a Th1 response. The role of TLR for the induction of anti-fungal Th17 cells is less clear. By using naive fungus-specific T cell receptor transgenic cells, a recent study demonstrated that TLR-induced MyD88 activity and not dectin-1 or IL-1R signaling, was required for the development of vaccine induced Th17 cells and resistance to B. dermatitidis infection (Wuthrich et al., 2011). The identity of the TLR driving this response is unknown. TLR are globally expressed on DC although some subsets of DC may express only a subset of TLR. For example, TLR3 is expressed 28-fold higher by CD8+ DC than by CD4+CD8- DC in the spleen (Edwards et al., 2003) suggesting that DC subsets are differentially activated by discrete fungal TLR ligands.

TLR2

While TLR-mediated signaling in DC generally favors the development of Th1 responses, TLR2 signaling may promote non-protective Th2 or Treg differentiation. TLR2 mediated recognition of C. albicans results in increased IL-10 production and a concurrent decrease in Th1 polarization (Netea et al., 2004). As a result, TLR2-/- mice showed increased resistance to disseminated candidiasis that was associated with increased IL-12 and IFN-γ and decreased IL-10 production. Further evidence for the anti-inflammatory role of TLR2 signaling in DC was provided by two additional studies. First, DC recognition of zymosan via TLR2 and dectin-1 promoted Treg cell differentiation via IL-10 and TGF-β secretion (Dillon et al., 2006). Second, live A. fumigatus hyphae reduced IL-12 and IL-23 production and increased IL-10 production from DC exposed to house dust mite extract in a TLR2 and dectin-1 dependent fashion, suggesting that TLR2 recognition of fungal ligands may promote tolerance rather than protective immunity.

TLR4

Recognition of fungal ligands by TLR4 similarly engenders heterogeneous responses that fail to recapitulate TLR4 mediated responses to the prototypical TLR4 ligand LPS. For example, recognition of C. albicans derived O-linked mannosyl residues by TLR4 promotes proinflammatory cytokines. By contrast, TLR4 binding of the C. neoformans cell wall component glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) does not induce cytokine production despite inducing NF-κB nuclear translocation. As TLR4 signaling in response to LPS requires the assembly of a larger complex consisting of CD14 and MD-2, it is likely that fungal recognition by TLR4 will require accessory signaling molecules that may mediate disparate TLR4 mediated responses to different fungal PAMP.

TLR3 TLR7 TLR9

Multiple studies have demonstrated that fungi are recognized by the endosomal nucleic acid sensing TLR: TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9. For instance, cryptococcal DNA triggered IL-12p40 and CD40 expression in murine DCs and activated NF-κB in TLR9-transfected HEK239 cells (Nakamura et al., 2008). Similarly, A. fumigatus DNA stimulated the production of proinflammatory cytokines in mouse and human DC (Ramirez-Ortiz et al., 2008). Drug-resistant Candida glabrata represents an important emerging opportunistic infection. A recent study demonstrated that C. glabrata induces Type I IFN secretion from DC in a TLR7-dependent, but TLR2- and TLR4- independent, manner (Bourgeois et al., 2011). TLR9 is often targeted with synthetic oligonucleotides that act as strong adjuvants in new vaccine designs. As more is learned about fungal recognition by these TLR and the responses they engender by DC, fungal ligands may provide additional tools to promote anti-fungal vaccine immunity.

CLR

Like the TLR, CLR recognize a broad range of PAMP present on fungi. CLR recognize glucan, mannose, or fucose containing structures on fungi and trigger intracellular signaling via ITAM-containing adaptor molecules leading to maturation of DC and the secretion of cytokines. DC express a wide range of CLR, although expression of some CLR are restricted to a particular subset of DC contributing to the functional differences of the DC subsets.

Dectin-1

Prior to the discovery of dectin-1 as the receptor for β-glucan, fungal β-glucans were already in use as powerful immunomodulators and vaccine adjuvants. The discovery of dectin-1 (Brown and Gordon, 2001) has allowed for greater elucidation of the mechanism by which β-glucans exert their effects. Dectin-1 signals via an intracellular domain containing a hemITAM motif that can recruit and activate the tyrosine kinase Syk. Recruitment of Syk by activated dectin-1 results in activation of MAPK, NFAT, and NF-κB via the CARD9 adaptor. Activation of dectin-1 by curdlan, a highly purified β-glucan, elicited IL-6, IL-23, and IL-12 from DC. Curdlan exposed DC loaded with antigen could drive differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th17 and Th1 cells, prime protective CTL cells, and promote antibody responses suggesting that dectin-1 links DC-recognition of β-glucans to both T cell and B cell adaptive immunity (Leibundgut-Landmann et al., 2008). While dectin-1 is critical for driving anti-fungal Th17 cells and resistance to C. albicans, A. fumigatus and Pneumocystis carinii, it was found that vaccine-induced Th17 cells and immunity to B. dermatitidis are dectin-1 independent (Wuthrich et al., 2011). Dectin-1 can also mediate uptake of fungi by DC via recognition of surface β-glucan. Many fungi, including H. capsulatum, mask β-glucan on their surfaces, highlighting the powerful role of dectin-1 in the recognition and response to fungi.

Dectin-2 and Mincle

While dectin-1 recognizes β-glucan, dectin-2 and Mincle recognize mannose-like structures and require the adaptor FcRγ to signal via Syk. Dectin-2 is most abundantly expressed on inflammatory monocytes and DC. Recognition of α-mannans by dectin-2 induces the secretion of IL-2, IL-10 and TNF-α by DC in vitro (Robinson et al., 2009). Furthermore, in a model of systemic C. albicans infection, dectin-2-/- mice or mice treated with a dectin-2 neutralizing mAb failed to develop Candida-specific Th17 cells. Mincle also induces the production of TNF-α, CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL-10 via Syk and CARD9 upon recognition of C. albicans, Malassezia sp. and Fonsecaea pedrosoi, yet whether Mincle engagement on DC by fungal PAMP promotes anti-fungal immunity remains to be investigated (Sousa Mda et al., 2011). Mincle, which also recognizes a mycobacterial glycolipid, is already the target of novel vaccine designs against mycobacterial pathogens and may prove to be a fruitful target in anti-fungal vaccination efforts.

The mannose receptor (CD206)

CD206 is a transmembrane protein that binds terminal mannose, N-acetyl glucosamine, or fucose sugars and that lacks classical signaling motifs. It can also be cleaved from the cell surface and exists as a soluble receptor in some circumstances. In response to fungal N-linked mannans, CD206 can induce NF-κB activation and the production of IL-12, GM-CSF, IL-8, IL-1β, and IL-6. CD206 also appears to be responsible for the formation of a novel DC phagocytic structure called the “fungipod” which may promote yeast phagocytosis by DC and play an important role in DC-fungi interactions (Neumann and Jacobson, 2010). The role of CD206 in promoting fungal antigen uptake, processing, and presentation by DC remains poorly understood. However due to the wide expression of CD206 on DC subsets, strategies to target vaccine antigen to CD206 could result in broad DC mobilization and potentially robust vaccine immunity.

NLR

Recently, a NOD-like receptor family member was found to play a role in the anti-fungal immunity. Exposure of monocytes to C. albicans germ tubes or A. fumigatus hyphae activated the NLRP3 inflammasome in a Syk-dependent fashion (Hise et al., 2009; Said-Sadier et al., 2010). NLRP3 is activated by a wide range of pathogen- and host-associated stimuli and it is unclear if NLRP3 senses stimuli directly or indirectly. β-glucan also activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in DC although this activation is dispensable for antigen specific Th1 and Th17 polarization (Kumar et al., 2009). Fungal structures recognized by NLRP3 may include surface carbohydrates, fungal DNA, or a fungal-induced host factor signifying tissue damage such as ATP. NLRP3 agonists such as aluminum hydroxide have been in use as vaccine adjuvants for decades, thus discerning the mechanism of fungal-induced NLPR3 activation could enhance future vaccine designs against fungi and other pathogens.

FUNGAL VACCINE STRATEGIES TARGETING DC

Only a single clinical trial evaluating efficacy of a fungal vaccine has been completed in humans (Pappagianis, 1993). A new interest in fungal vaccine development has accompanied the growing knowledge illuminating the critical determinants of host defense against fungal pathogens. More importantly, recent work suggests that it may be possible to create an anti-fungal vaccine that grants protection against multiple fungal pathogens (Wuthrich et al., 2011; Stuehler et al., 2011; Cassone and Rappuoli, 2010). At the core of host resistance to fungi, is the induction of strong cellular immunity via appropriate activation of DC. Anti-viral and anti-tumor vaccine strategies have leveraged the central role of DC in driving CTL responses by first priming autologous monocyte-derived DC with the desired antigen ex vivo before re-administering the loaded DC to the host. In animal models, DC primed with fungi ex vivo promote antifungal immunity in naïve mice. Similarly, DC transfected with fungal RNA ex vivo express fungal proteins on their surface and promote the development of protective T cell responses (Bozza et al., 2004). These procedures are time-consuming and expensive and for those reasons they are unlikely to be widely adopted in clinical medicine. However, recent technological advances in antigen delivery combined with a greater understanding of DC biology, should allow for effective targeting and loading of DC with immunogenic antigen in vivo.

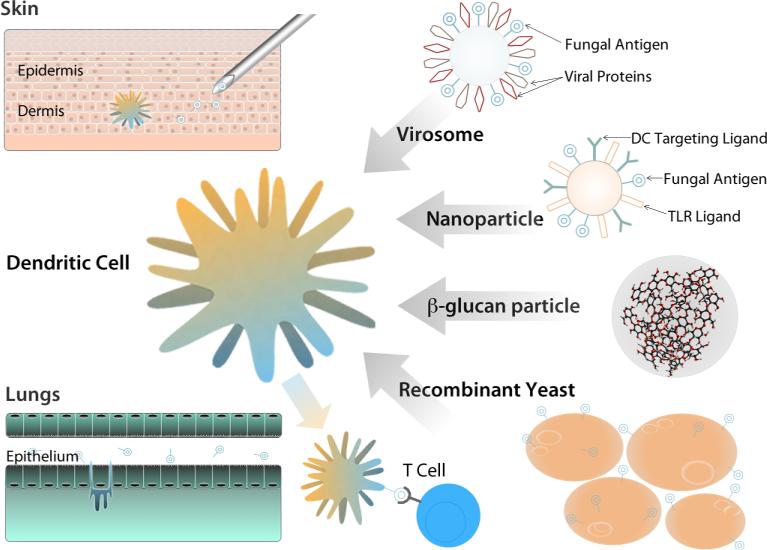

Because of the dense network of DC in the skin, the lung, and the intestine, vaccine delivery systems that target these DC networks may be more potent (Fig 3). Indeed, when comparing influenza vaccine injection routes, intradermal injection was more than twice as potent at eliciting antibodies than subcutaneous administration in individuals between 18 and 60 years of age (Belshe et al., 2004). A current Phase I clinical trial expected to be completed in early 2012 is evaluating the safety of intravaginal application of a virosome-based recombinant Sap2 therapeutic vaccine against recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) (NCT01067131). Pre-clinical trials in mice demonstrated rapid clearance of Candida and protection from reoccurrence in a murine VVC model following intravaginal administration of the vaccine (Sandini et al., 2011). However, vaccination at these DC rich sites may not represent a universal approach to vaccination against fungi. For example, a live attenuated strain of B. dermatitidis engendered full protection when administered subcutaneously but not when administered intranasally against a lethal pulmonary challenge in mice (Wuthrich et al., 2000). Correspondingly, CCR2-/- mice lacking monocyte-derived inflammatory DC had impaired clearance of A. fumigatus from the lung but not the spleen demonstrating an organ specific role for this DC subset (Hohl et al., 2009). The tissue microenvironment also modulates the function of DC subsets and influences the ability of DC to prime effective T cell responses. DC subsets in the spleen are able to drive Th17 differentiation in the absence of IL-6 whereas DC from the skin and the gut require IL-6 to drive Th17 polarization (Hu et al., 2011). This suggests that the effect of local cytokine generation will need to be factored into fungal vaccine design when considering a route of vaccination. Thus, the DC subtypes and the tissue microenvironment at the vaccination site may critically modulate vaccine responses to fungal antigens.

Figure 3. DC-based strategies for developing anti-fungal vaccines.

DC subsets may be targeted by varying the route of administration; aerosols target lung DC subsets, intradermal injection targets skin DC. DC can be loaded directly ex vivo before transfer into the host. Recombinant yeast contain ligands recognized by DC and allow for efficient DC uptake of antigen expressing organisms. β–glucan particles robustly activate DC via dectin-1. Virosomes also contain DC targeting ligands and viral PRR ligands that activate DC. Nanoparticles represent a complete engineered solution that incorporates PRR ligands, DC targeting ligands, and vaccine antigens. Following DC targeting, mature DC present antigen and activate naïve T cells.

A more direct method to target DC is to covalently attach antigen to DC-specific ligands. Fungal pathogens contain substantially mannosylated proteins which are effectively endocytosed by DC via CLR. In fact, mannosylation of the model antigen OVA greatly enhanced its immunogenicity at least in part by increasing its uptake by DC via CLR family members CD206 and DC-SIGN (CD209) (Lam et al., 2007). Other fungal carbohydrates also effectively target antigen to DC. For example, antigen loaded β-glucan particles are actively taken up by DC in a dectin-1 dependent manner. OVA-laden-β-glucan-particle exposed DC were more potent at inducing proliferation of OVA specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro compared with soluble OVA (Huang et al., 2010). Furthermore, subcutaneous administration of OVA-laden-β-glucan-particles induced higher OVA-specific T cell polarization toward a Th1 and Th17 phenotype than alum-adsorbed OVA and induced the secretion of OVA-specific Th1 associated IgG2c antibodies. Incredibly, fungi themselves are now being exploited to take advantage of direct targeting and robust activation of DC via the β-glucan/Dectin-1 interaction. In whole recombinant yeast immunization, antigen-expressing S. cerevisiae yeast (which display β-glucan on their surface) are administered with the goal of eliciting antigen-specific host CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses (Stubbs et al., 2001). Completed Phase I trials indicate that S. cerevisiae based therapies are safe and well tolerated in humans and Phase II trials are currently ongoing (NCT00124215).

A complementary approach to whole recombinant yeast immunization involves the use of nanoparticles in targeting antigen to DC. Nanoparticles are internalized preferentially by DC due to their sub-micron size and can be more specifically targeted to DC through the addition of DC receptor (such as Dec 205) targeting antibodies or DC receptor ligands to their surface. Nanoparticle mediated targeting of DC enables the bundling of defined antigen or antigens with an adjuvant and a DC receptor targeting molecule allowing for precise delivery to DC. The elegance of this approach was recently demonstrated using a DEC205 F(ab')2 fragment coated nanoparticle containing TLR3, TLR7, & TLR8 ligands and OVA antigen (Tacken et al., 2011). This nanoparticle was designed to target DEC205+ DC and to simultaneously deliver the antigen and TLR ligand adjuvant. Targeting of the particles to DC enhanced their immunogenicity, encapsulating the antigen (OVA) increased the potency of the antigen, and co-delivering TLR ligands blocked the development of tolerance and reduced overall toxicity. In total, the study suggests that nanoparticles can deliver vaccine antigen to DC effectively, and that when antigen and adjuvant are delivered together, strong immune responses with limited toxicity can be induced. In a limited way, the targeting nanoparticle loaded with antigen and adjuvant begins to resemble the microbial vaccine target itself.

Since the surfaces of fungi are covered in polysaccharide, carbohydrate or glycoconjugate antigens, they are attractive targets for anti-fungal vaccine development. Vaccine strategies based on both the glucuronoxylomannan component of the cryptococcal polysaccharide capsule and β-1,3-glucan that is expressed by a broad range of fungi have demonstrated the ability to promote antibody mediated protection against fungal challenge. However, immunogenicity of glycoconjugates is unpredictable and the carbohydrate moiety is thought unable to be recognized by T cells directly. Novel findings using a defined glycoconjugate suggest that it is possible to design vaccines where T cells recognize the carbohydrate directly and that such glycoconjugates greatly enhance immunogenicity (Avci et al., 2011). It is tantalizing to speculate that fungal carbohydrates displayed by MHC II could be recognized by T cells in the same way. Immunization with glycosylated peptides was able to generate carbohydrate specific CTL responses (Abdel-Motal et al., 1996) suggesting that appropriately designed glycoconjugates may be processed and cross-presented to CD8+ T cells. As knowledge of cross-presentation by DC increases, it may be possible to generate fungal carbohydrate specific CTL responses against fungal pathogens. This may be advantageous in immune deficient patients lacking CD4+ T cells, where CD8 T cells compensate and mediate lasting vaccine-induced resistance to pathogenic fungi (Nanjappa et al., 2012).

CONCLUSIONS

In this review, we have highlighted the role of diverse DC subsets in anti-fungal immunity and discussed potential strategies to target DC in the generation of novel anti-fungal vaccines. Vaccines may be targeted to DC via interactions with surface receptors or via other routes of administration and activate DC through PRR. New vaccine construction technologies are expanding the available pool of fungal antigens that induce cell-mediated immunity to include carbohydrates and reduce toxicity. Continuing to unearth the central role of DC in anti-fungal immunity will suggest new avenues for the development of effective anti-fungal vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by grants from the USPHS (AI35681 and AI40996 to BK; and NIEHS T32ES007015 and F30ES019048 to RR). We thank Dr. Carrie Roy for her assistance with graphic design and illustration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Abdel-Motal UM, Berg L, Rosen A, Bengtsson M, Thorpe CJ, Kihlberg J, Dahmen J, Magnusson G, Karlsson KA, Jondal M. Immunization with glycosylated Kb-binding peptides generates carbohydrate-specific, unrestricted cytotoxic T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:544–551. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan RS, Waithman J, Bedoui S, Jones CM, Villadangos JA, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Shortman K, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity. 2006;25:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avci FY, Li X, Tsuji M, Kasper DL. A mechanism for glycoconjugate vaccine activation of the adaptive immune system and its implications for vaccine design. Nat Med. 2011;17:1602–1609. doi: 10.1038/nm.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer R, van Leeuwen F, Kraal G, den Haan JM. CD8- dendritic cells preferentially cross-present Saccharomyces cerevisiae antigens. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:370–380. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty SR, Rose CEJ, Sung SS. Diverse and potent chemokine production by lung CD11bhigh dendritic cells in homeostasis and in allergic lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178:1882–1895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belshe RB, Newman FK, Cannon J, Duane C, Treanor J, Van Hoecke C, Howe BJ, Dubin G. Serum antibody responses after intradermal vaccination against influenza. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2286–2294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin DKJ, Stoll BJ, Gantz MG, Walsh MC, Sanchez PJ, Das A, Shankaran S, Higgins RD, Auten KJ, Miller NA, Walsh TJ, Laptook AR, Carlo WA, Kennedy KA, Finer NN, Duara S, Schibler K, Chapman RL, Van Meurs KP, Frantz I. D. r., Phelps DL, Poindexter BB, Bell EF, O'Shea TM, Watterberg KL, Goldberg RN. Neonatal candidiasis: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical judgment. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e865–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitar D, Van Cauteren D, Lanternier F, Dannaoui E, Che D, Dromer F, Desenclos JC, Lortholary O. Increasing incidence of zygomycosis (mucormycosis), France, 1997-2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1395–1401. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza S, Montagnoli C, Gaziano R, Rossi G, Nkwanyuo G, Bellocchio S, Romani L. Dendritic cell-based vaccination against opportunistic fungi. Vaccine. 2004;22:857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois C, Majer O, Frohner IE, Lesiak-Markowicz I, Hildering KS, Glaser W, Stockinger S, Decker T, Akira S, Muller M, Kuchler K. Conventional dendritic cells mount a type I IFN response against Candida spp. requiring novel phagosomal TLR7-mediated IFN-beta signaling. J Immunol. 2011;186:3104–3112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD. Innate antifungal immunity: the key role of phagocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011;29:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune recognition. A new receptor for beta-glucans. Nature. 2001;413:36–37. doi: 10.1038/35092620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassone A, Rappuoli R. Universal vaccines: shifting to one for many. MBio. 2010;1(1):e00042–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00042-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorro L, Sarde A, Li M, Woollard KJ, Chambon P, Malissen B, Kissenpfennig A, Barbaroux JB, Groves R, Geissmann F. Langerhans cell (LC) proliferation mediates neonatal development, homeostasis, and inflammation-associated expansion of the epidermal LC network. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3089–3100. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler JE, Deepe GSJ, Klein BS. Advances in combating fungal diseases: vaccines on the threshold. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:13–28. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio ML, Rodriguez-Barbosa JI, Kremmer E, Forster R. CD103- and CD103+ bronchial lymph node dendritic cells are specialized in presenting and cross-presenting innocuous antigen to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:6861–6866. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Haan JM, Lehar SM, Bevan MJ. CD8(+) but not CD8(-) dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1685–1696. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning TL, Norris BA, Medina-Contreras O, Manicassamy S, Geem D, Madan R, Karp CL, Pulendran B. Functional specializations of intestinal dendritic cell and macrophage subsets that control Th17 and regulatory T cell responses are dependent on the T cell/APC ratio, source of mouse strain, and regional localization. J Immunol. 2011;187:733–747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desch AN, Randolph GJ, Murphy K, Gautier EL, Kedl RM, Lahoud MH, Caminschi I, Shortman K, Henson PM, Jakubzick CV. CD103+ pulmonary dendritic cells preferentially acquire and present apoptotic cell-associated antigen. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1789–1797. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S, Agrawal S, Banerjee K, Letterio J, Denning TL, Oswald-Richter K, Kasprowicz DJ, Kellar K, Pare J, van Dyke T, Ziegler S, Unutmaz D, Pulendran B. Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:916–928. doi: 10.1172/JCI27203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez PM, Ardavin C. Differentiation and function of mouse monocyte-derived dendritic cells in steady state and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:90–104. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, Cheong C, Liu K, Lee HW, Park CG, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AD, Diebold SS, Slack EM, Tomizawa H, Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Toll-like receptor expression in murine DC subsets: lack of TLR7 expression by CD8 alpha+ DC correlates with unresponsiveness to imidazoquinolines. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:827–833. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersland K, Wuthrich M, Klein BS. Dynamic interplay among monocyte-derived, dermal, and resident lymph node dendritic cells during the generation of vaccine immunity to fungi. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:474–487. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferwerda B, Ferwerda G, Plantinga TS, Willment JA, van Spriel AB, Venselaar H, Elbers CC, Johnson MD, Cambi A, Huysamen C, et al. Human Dectin-1 Deficiency and Mucocutaneous Fungal Infections. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:1760–1767. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg DK, Sibon C, Miled C, Jung S, Aucouturier P, Littman DR, Cumano A, Geissmann F. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science. 2006;311:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F, Collin MP, Bogunovic M, Abel M, Leboeuf M, Helft J, Ochando J, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Grisotto M, Snoeck H, Randolph G, Merad M. Blood-derived dermal langerin+ dendritic cells survey the skin in the steady state. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3133–3146. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henri S, Guilliams M, Poulin LF, Tamoutounour S, Ardouin L, Dalod M, Malissen B. Disentangling the complexity of the skin dendritic cell network. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010a;88:366–375. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henri S, Poulin LF, Tamoutounour S, Ardouin L, Guilliams M, de Bovis B, Devilard E, Viret C, Azukizawa H, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B. CD207+ CD103+ dermal dendritic cells cross-present keratinocyte-derived antigens irrespective of the presence of Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2010b;207:189–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hise AG, Tomalka J, Ganesan S, Patel K, Hall BA, Brown GD, Fitzgerald KA. An essential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohl TM, Rivera A, Lipuma L, Gallegos A, Shi C, Mack M, Pamer EG. Inflammatory monocytes facilitate adaptive CD4 T cell responses during respiratory fungal infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh SH, Lin JS, Huang JH, Wu SY, Chu CL, Kung JT, Wu-Hsieh BA. Immunization with apoptotic phagocytes containing Histoplasma capsulatum activates functional CD8(+) T cells to protect against histoplasmosis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4493–4502. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05350-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Troutman TD, Edukulla R, Pasare C. Priming microenvironments dictate cytokine requirements for T helper 17 cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2011;35:1010–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Ostroff GR, Lee CK, Specht CA, Levitz SM. Robust stimulation of humoral and cellular immune responses following vaccination with antigen-loaded beta-glucan particles. MBio. 2010;1(3):e00164–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00164-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Cattamanchi A, Davis JL, Boon S.d., Kovacs J, Meshnick S, Miller RF, Walzer PD, Worodria W, Masur H, et al. HIV-Associated Pneumocystis Pneumonia. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2011;8:294–300. doi: 10.1513/pats.201009-062WR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idoyaga J, Suda N, Suda K, Park CG, Steinman RM. Antibody to Langerin/CD207 localizes large numbers of CD8alpha+ dendritic cells to the marginal zone of mouse spleen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1524–1529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812247106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igyarto BZ, Haley K, Ortner D, Bobr A, Gerami-Nejad M, Edelson BT, Zurawski SM, Malissen B, Zurawski G, Berman J, Kaplan DH. Skin-resident murine dendritic cell subsets promote distinct and opposing antigen-specific T helper cell responses. Immunity. 2011;35:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnsen FL, Strickland DH, Thomas JA, Tobagus IT, Napoli S, Zosky GR, Turner DJ, Sly PD, Stumbles PA, Holt PG. Accelerated antigen sampling and transport by airway mucosal dendritic cells following inhalation of a bacterial stimulus. J Immunol. 2006;177:5861–5867. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Kumagai Y, Tsuchida T, Koenig PA, Satoh T, Guo Z, Jang MH, Saitoh T, Akira S, Kawai T. Involvement of the NLRP3 inflammasome in innate and humoral adaptive immune responses to fungal beta-glucan. J Immunol. 2009;183:8061–8067. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam JS, Huang H, Levitz SM. Effect of differential N-linked and O-linked mannosylation on recognition of fungal antigens by dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibundgut-Landmann S, Osorio F, Brown GD, Reis ESC. Stimulation of dendritic cells via the Dectin-1 / Syk pathway allows priming of cytotoxic T cell responses. Blood. 2008;112:4971–4980. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelouard H, Fallet M, de Bovis B, Meresse S, Gorvel JP. Peyer's Patch Dendritic Cells Sample Antigens by Extending Dendrites Through M Cell-Specific Transcellular Pores. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:592–601.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HS, Gelbard A, Martinez GJ, Esashi E, Zhang H, Nguyen-Jackson H, Liu YJ, Overwijk WW, Watowich SS. Cell-intrinsic role for IFN-alpha-STAT1 signals in regulating murine Peyer patch plasmacytoid dendritic cells and conditioning an inflammatory response. Blood. 2011;118:3879–3889. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-349761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JS, Yang CW, Wang DW, Wu-Hsieh BA. Dendritic cells cross-present exogenous fungal antigens to stimulate a protective CD8 T cell response in infection by Histoplasma capsulatum. J Immunol. 2005;174:6282–6291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Nussenzweig MC. Origin and development of dendritic cells. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, Yao K, Chu FF, Randolph GJ, Rudensky AY, Nussenzweig M. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science. 2009;324:392–397. doi: 10.1126/science.1170540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber CA, Cox J, Lauterbach H, Fancke B, Selbach M, Tschopp J, Akira S, Wiegand M, Hochrein H, O'Keeffe M, Mann M. Quantitative proteomics reveals subset-specific viral recognition in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;32:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means TK, Mylonakis E, Tampakakis E, Colvin RA, Seung E, Puckett L, Tai MF, Stewart CR, Pukkila-Worley R, Hickman SE, Moore KJ, Calderwood SB, Hacohen N, Luster AD, El Khoury J. Evolutionarily conserved recognition and innate immunity to fungal pathogens by the scavenger receptors SCARF1 and CD36. J Exp Med. 2009;206:637–653. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik SH. Demystifying the development of dendritic cell subtypes, a little. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:439–452. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Miyazato A, Xiao G, Hatta M, Inden K, Aoyagi T, Shiratori K, Takeda K, Akira S, Saijo S, Iwakura Y, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Suzuki K, Fujita J, Kaku M, Kawakami K. Deoxynucleic acids from Cryptococcus neoformans activate myeloid dendritic cells via a TLR9-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 2008;180:4067–4074. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjappa SG, Heninger E, Wuthrich M, Sullivan T, Klein B. Protective antifungal memory CD8+ T cells are maintained in the absence of CD4+ T cell help and cognate antigen in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:987–999. doi: 10.1172/JCI58762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Sutmuller R, Hermann C, Van der Graaf CA, Van der Meer JW, van Krieken JH, Hartung T, Adema G, Kullberg BJ. Toll-like receptor 2 suppresses immunity against Candida albicans through induction of IL-10 and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:3712–3718. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann AK, Jacobson K. A novel pseudopodial component of the dendritic cell anti-fungal response: the fungipod. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000760. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterholzer JJ, Chen GH, Olszewski MA, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. Accumulation of CD11b+ lung dendritic cells in response to fungal infection results from the CCR2-mediated recruitment and differentiation of Ly-6Chigh monocytes. J Immunol. 2009;183:8044–8053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappagianis D. Evaluation of the protective efficacy of the killed Coccidioides immitis spherule vaccine in humans. The Valley Fever Vaccine Study Group. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:656–660. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Ortiz ZG, Lee CK, Wang JP, Boon L, Specht CA, Levitz SM. A nonredundant role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Ortiz ZG, Specht CA, Wang JP, Lee CK, Bartholomeu DC, Gazzinelli RT, Levitz SM. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent immune activation by unmethylated CpG motifs in Aspergillus fumigatus DNA. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2123–2129. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00047-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera A, Ro G, Van Epps HL, Simpson T, Leiner I, Sant'Angelo DB, Pamer EG. Innate immune activation and CD4+ T cell priming during respiratory fungal infection. Immunity. 2006;25:665–675. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MJ, Osorio F, Rosas M, Freitas RP, Schweighoffer E, Gross O, Verbeek JS, Ruland J, Tybulewicz V, Brown GD, Moita LF, Taylor PR, Reis e Sousa C. Dectin-2 is a Syk-coupled pattern recognition receptor crucial for Th17 responses to fungal infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2037–2051. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said-Sadier N, Padilla E, Langsley G, Ojcius DM. Aspergillus fumigatus stimulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through a pathway requiring ROS production and the Syk tyrosine kinase. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandini S, La Valle R, Deaglio S, Malavasi F, Cassone A, De Bernardis F. A highly immunogenic recombinant and truncated protein of the secreted aspartic proteases family (rSap2t) of Candida albicans as a mucosal anticandidal vaccine. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;62:215–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sczesnak A, Segata N, Qin X, Gevers D, Petrosino JF, Huttenhower C, Littman DR, Ivanov II. The genome of th17 cell-inducing segmented filamentous bacteria reveals extensive auxotrophy and adaptations to the intestinal environment. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa Mda G, Reid DM, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Ruland J, Langhorne J, Yamasaki S, Taylor PR, Almeida SR, Brown GD. Restoration of pattern recognition receptor costimulation to treat chromoblastomycosis, a chronic fungal infection of the skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J Exp Med. 1973;137:1142–1162. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs AC, Martin KS, Coeshott C, Skaates SV, Kuritzkes DR, Bellgrau D, Franzusoff A, Duke RC, Wilson CC. Whole recombinant yeast vaccine activates dendritic cells and elicits protective cell-mediated immunity. Nat Med. 2001;7:625–629. doi: 10.1038/87974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuehler C, Khanna N, Bozza S, Zelante T, Moretti S, Kruhm M, Lurati S, Conrad B, Worschech E, Stevanovic S, Krappmann S, Einsele H, Latge JP, Loeffler J, Romani L, Topp MS. Cross-protective TH1 immunity against Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans. Blood. 2011;117:5881–5891. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung SS, Fu SM, Rose CEJ, Gaskin F, Ju ST, Beaty SR. A major lung CD103 (alphaE)-beta7 integrin-positive epithelial dendritic cell population expressing Langerin and tight junction proteins. J Immunol. 2006;176:2161–2172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak WA, Deepe GSJ. The CCL7-CCL2-CCR2 axis regulates IL-4 production in lungs and fungal immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:1964–1974. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak WA, Deepe GSJ. Antigen-presenting dendritic cells rescue CD4-depleted CCR2-/- mice from lethal Histoplasma capsulatum infection. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2125–2137. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00065-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taborda CP, Casadevall A. CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) are involved in complement-independent antibody-mediated phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Immunity. 2002;16:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacken PJ, Zeelenberg IS, Cruz LJ, van Hout-Kuijer MA, van de Glind G, Fokkink RG, Lambeck AJ, Figdor CG. Targeted delivery of TLR ligands to human and mouse dendritic cells strongly enhances adjuvanticity. Blood. 2011;118:6836–6844. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H, Fukaya T, Eizumi K, Sato Y, Sato K, Shibazaki A, Otsuka H, Hijikata A, Watanabe T, Ohara O, Kaisho T, Malissen B, Sato K. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Are Crucial for the Initiation of Inflammation and T Cell Immunity In Vivo. Immunity. 2011;35:958–71. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich M, Filutowicz HI, Klein BS. Mutation of the WI-1 gene yields an attenuated blastomyces dermatitidis strain that induces host resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1381–1389. doi: 10.1172/JCI11037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich M, Gern B, Hung CY, Ersland K, Rocco N, Pick-Jacobs J, Galles K, Filutowicz H, Warner T, Evans M, Cole G, Klein B. Vaccine-induced protection against 3 systemic mycoses endemic to North America requires Th17 cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:554–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI43984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, Montagnoli C, Bozza S, Moretti S, Belladonna ML, Vacca C, Conte C, Mosci P, Bistoni F, Puccetti P, Kastelein RA, Kopf M, Romani L. IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2695–2706. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]