Abstract

DNA damage-induced phospho-signaling has been studied for decades, with a focus mainly on initiation of the signaling cascade, and the kinases activated by DNA lesions. It is widely accepted that the balance of phosphorylation needs to be restored and/or maintained by phosphatases, yet there have only been sporadic efforts to investigate the impact of phosphatases on DNA repair. Recent advances in phosphoproteomic strategies and implementation of large genetic screens indicate that these enzymes play pivotal roles in these signaling networks. Dephosphorylation of repair proteins is critical for efficient DNA repair, and the recommencement of cell division post-repair. Here, we focus on serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in dephosphorylation of DNA repair factors, summarizing recent findings and speculating on un-tested roles of phosphatases in the DNA damage response (DDR).

DNA damage and phospho-signaling

The cellular response to double-strand DNA breaks (DSB)s (Box 1) is initiated by the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase-like (PI3-like) family of kinases, which includes DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), and ataxia telangiectasia- and Rad3-related (ATR). In mammalian cells these kinases phosphorylate ∼700 proteins in response to exogenous DNA damage [1, 2]. The DSB-induced phosphorylation network is further amplified by the checkpoint kinases, CHK1 and CHK2, the polo-like kinases (PLKs), and MK2 (also called CHK3) [3-6]. The phosphorylated proteins include factors involved in DNA replication and repair, apoptosis, and/or cell cycle progression. Functional consequences of phosphorylation have been studied for a small subset of these factors; such events typically exhibit a clear impact on the DDR. There is limited information on the kinetics of phosphorylation and the mechanism of down-modulating the signaling network. Phosphatases are obvious candidates for this regulatory step, and could conceivably maintain the balance of phosphorylation during and after the DDR. Recent studies [7, 8] investigating the dynamics of phosphorylation following DNA damage show that there is considerable variation in the kinetics and direction of phosphoproteomic changes. 753 phosphorylation sites mapping to 394 proteins were altered in response to a radiomimetic agent, neocarzinostatin, and an astounding 342 of these sites represented dephosphorylation events [8]. Over one-third of the captured phosphopeptides were dephosphorylated within minutes of DNA damage. Interestingly, these phosphopeptides not only represent substrates of PI3-like kinases but also include substrates of constitutively active casein kinase (CK) family members and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). These data suggest that phosphatases not only play a role in counter-acting DSB-induced phosphorylation events, but also play a primary role in initiating the repair process by dephosphorylating proteins. In recent years there have been several insightful reports on the function of Serine (Ser)/Threonine (Thr) phosphatases (Box 2) in DNA repair. Here we will discuss these recent observations and speculate on the potential role of these phosphatases in regulating the DDR.

Box 1. DNA damage response (DDR) to DSB.

Cells are constantly challenged by DNA damage arising from endogenous and exogenous sources, including reactive oxygen species, ultraviolet light, and environmental mutagens. To overcome this challenge, cells have developed a surveillance mechanism that monitors genotoxic stress and loads an orchestrated response, including cell cycle checkpoint activation, transcriptional program activation, DNA repair, and apoptosis. This is collectively termed as the DNA damage response (DDR; Figure I). Among the DNA lesions, DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) are considered to be the most deleterious: a single DSB can induce cell death. DSBs are repaired by two major pathways: (a) homologous recombination (HR) and (b) non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). HR requires an undamaged homologous DNA template to replace an adjacent damaged one with high fidelity and is believed to occur preferentially during late S and G2. By contrast, the untemplated NHEJ pathway joins two DNA ends irrespective of their sequence, thereby generating errors if the two ends are unrelated or inaccurately processed. NHEJ is not limited to any cell cycle phase and is proposed to be predominant in differentiated cells and quiescent cells [45].

Figure I. The cellular response to DNA DSBs.

Box 2. Serine/Threonine Phosphatases.

Proteins phosphatases are classified into three groups: Ser/Thr phosphatases (PPP and PPM; Table I), protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) and haloacid dehalogenase (HAD). The PPP family is subdivided into the PP1, PP2A, PP2B, PP4, PP5, PP6, and PP7 members based on sequence, structure, and biochemical properties. ∼40 Ser/Thr phosphatase catalytic subunits are responsible for dephosphorylating the majority of Ser/Thr phosphoresidues. This would suggest wanton phosphatase activity in cells, but, like most other cellular enzymes, phosphatases are highly regulated, and catalytic activity is typically harnessed by a large number of regulatory subunits. The functional diversity and specificity of these enzymes is conferred by their distinct regulatory or targeting subunits [11].

Table I. Serine/Threonine Phosphatases.

| Catalytic subunit | Regulatory subunit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ser/Thr phosphatase | |||

| PPP | PP1 | C(α, β, γ) | PP1-interacting proteins (PIPs, more than 90) |

| PP2A | C(α, β) | Scaffolding A subunit (α, β) Regulatory B subunit (PR55,PR61, PR72) | |

| PP4 | C | PP4R1, PP4R2, PP4R3α, PP4R3β, PP4R4 | |

| PP5 | C | None | |

| PP6 | C | PP6R1, PP6R2, PP6R3 | |

| PP7 | C | Unknown | |

| PP2B | PP3C(α, β, γ) | Calcineurin B or CNB | |

| PPM | PP2C | PP2C(α,β,γ,δ,ε,ζ, η,κ), CaMKP, CaMKP-N, ILKAP, PHLPP, NERRP-2C, TA-PP2C, PDP1, PDP2 | None |

Serine/Threonine Phosphatases

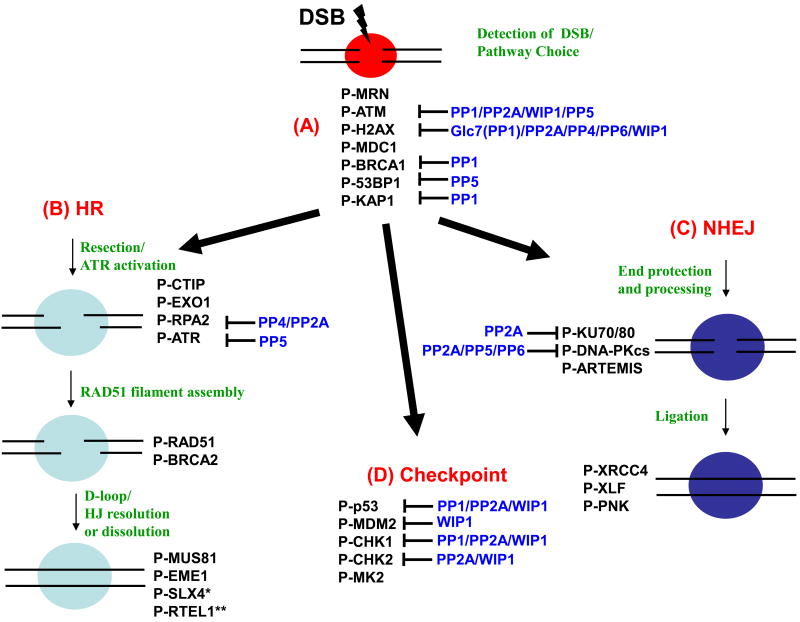

Ser/Thr phosphatases have been classified based on sequence, structure and biochemical properties (e.g. metal dependence). So far, only a handful of Ser/Thr phosphatases have been implicated in the DDR (Figure 1). This list includes mainly the phosphoprotein phosphatase (PPP) family members (PP1, PP2A-like phosphatases, PP5) and the Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent phosphatase (PPM) family member, WIP1 (also termed PP2Cδ or PPMID).

Figure 1. Ser/Thr phosphatases involved in the DSB repair pathways and checkpoint control.

This is a schematic depicting a selection of factors involved in the DDR that are phosphorylated in response to DSBs. Phosphatases (indicated in blue text) regulate a small subset of these factors. (A) DNA repair proteins that are potentially involved in the choice of repair pathway (the MRN complex [MRE11–RAD50–NBS1], ATM, H2AX, MDC1, BRCA1, 53BP1, and KAP1) and in the initiation stage of the repair process. (B) Homologous Recombination (HR) is promoted in S and G2 phase. MRN initiates resection at the DSB site with CTIP and EXO1 followed by RPA accumulation on single strand DNA. BRCA2 mediates the displacement of RPA, and formation of recombinogenic RAD51 filaments. Strand invasion by RAD51 filaments results in formation of D loops which are resolved by the anti-recombinase RTEL1 {**undergoes dephosphorylation after DNA damage [8]}. Unresolved D-loops can result in Holliday Junctions (HJ) which are resolved by SLX4 (* phosphomimetic mutants have distinct phenotype [100], implying the importance of dephosphorylation) with MUS81/EME1. (C) Non-homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is dominant in G1 phase. Ku proteins are rapidly recruited to DSB sites to tether DSB ends and activate DNA-PK, and to facilitate NHEJ. DNA-PK stabilizes DSB ends and prevents resections through autophosphorylation and its activity is regulated by multiple phosphatases. Ligatable ends are processed by ARTEMIS, and ligation is enhanced by XRCC4/XLF/PNK. (D) Check point regulation. Proliferating cells go through G1/S, intra-S, and G2/M checkpoints prior to entering mitosis. The indicated proteins are involved in these checkpoints.

PP1

PP1 is a ubiquitously expressed, abundant phosphatase involved in a variety of cellular functions including RNA processing, mitotic progression, checkpoint activation, and DNA repair. It has three catalytic subunits – PP1α, PP1β, and PP1γ – and can form as many as 650 distinct complexes with PP1-interacting proteins (PIPs). PIPs include bona fide PP1 substrates, substrate-targeting proteins, substrate-specifiers and inhibitors [9-11]. PP1 has a role in initiation of the DSB-signaling cascade: ATM remains inactive in unperturbed cells owing to the dephosphorylation of Ser1981 by the Repo-Man (Recruits PP1 onto mitotic chromatin at anaphase)–PP1γ complex. Upon induction of DSBs, Repo-Man dissociates from ATM, thereby facilitating ATM activation and initiation of the DDR [12]. Breast cancer associated gene 1, (BRCA1), a critical player in the homologous recombination (HR) repair pathway, binds PP1 via a conserved targeting motif (RVxF). Disrupting the BRCA1–PP1 interaction or depleting PP1α in BRCA1-proficient cells results in impaired HR-mediated DSB repair [13, 14]. PP1 homologues in yeast directly impact the cell cycle checkpoints by dephosphorylating Rad53 (CHK2 homologue) [15] and Chk1 [16]. In cycling mammalian cells CHK1-mediated phosphorylation of Histone-H3 at Thr11 marks transcriptionally active loci. After DNA damage, phosphorylated CHK1 dissociates from histones and PP1γ dephosphorylates H3 p-Thr11; this blocks transcription and promotes DNA repair [17]. Another factor, KAP1 (also known as TRIM28, TIF-1β), a transcriptional repressor that is phosphorylated by ATM in response to DSBs, was recently reported to be a substrate of PP1 [18].

PP2A-like phosphatases

The PP2A-like phosphatase family comprises PP2A, PP4 and PP6. The members have significant homology in their primary amino acid sequence and comparable sensitivity to chemical inhibitors, including okadaic acid. Each phosphatase catalytic subunit forms a multimeric complex with regulatory and scaffolding subunits and these interactions are critical for substrate specificity [19].

PP2A

PP2A is one of the most well-studied phosphatases and impinges on a broad spectrum of cellular functions, from cell metabolism to survival [20]. It operates as a heterotrimeric complex, consisting of a catalytic subunit (PPP2Cα and PPP2Cβ), a scaffolding subunit (Aα and Aβ), and a variable regulatory subunit (B). The functional diversity of PP2A largely comes from the B subunit, which directs substrate specificity and subcellular localization [21, 22]. PP2A has a profound impact on the DDR by regulating activity of the primary (ATM, ATR and DNA-PK) [23-26] and secondary (CHK1 and CHK2) [27-31] kinases involved in the signaling cascade. It also de-phosphorylates downstream targets, such as γ-H2AX, at DSB sites and broadly influences repair of DSBs [32, 33]. More specifically, PP2A promotes the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway for repair of DSBs by dephosphorylation of Ku70–Ku80 and DNA-PK [34]. Distinct from PP1, PP5 and other PP2A-like phosphatases, PP2A has a profound impact on IR-induced G2/M arrest [30]. Silencing/inhibiting PP2A causes an impaired DDR, but this phenotype cannot be attributed to any individual PP2A-substrate. An intricate pattern of phosphorylation involving ∼20 phosphosites is critical for the multifaceted presence of p53 in the DDR [35]. PP2A is part of this quagmire. It regulates the transcriptional activity of p53 by reversing the IR-induced phosphorylation of p53 at Ser37 and Ser15 [36, 37], and a PP2AC– B56γ complex stabilizes p53 after DNA damage by dephosphorylating p53 at Thr55 [37-39]. As the story of p53 continues to evolve, the role of PP2A in this saga will be better understood.

PP4

PP4C has 65% homology with PP2AC and functions in complex with regulatory subunits (PP4R1, PP4R2, PP4R3α, PP4R3β, and PP4R4) that are distinct from PP2A [40-44]. PP4 was recently recognized as a critical phosphatase in the DDR [45]: it dephosphorylates γ-H2AX, and phospho-RPA2 (replication protein A2), thereby facilitating efficient DNA repair and release from checkpoint control [33, 46, 47]). In contrast to PP4, deletion of its yeast homolog Pph3 has a mild cellular phenotype and no impact on DNA repair [48]. Pph3 dephosphorylates γ-H2AX and Rad53 and regulates checkpoint control [48-51]. Two other homologous phosphatases, Ptc2 and Ptc3, also dephosphorylate Rad53 and allow recovery from DNA damage checkpoint [52]. In Pph3 or Ptc2-depleted cells, Rad53 deactivation and re-start of the replication fork after DNA damage is delayed but not blocked. Intriguingly, the co-depletion of Ptc2, Ptc3 and Pph3 leads to a profound defect in DSB repair, with an additive impact on the kinetics of Rad53 dephosphorylation [52]. This finding suggests that the phosphatases have a redundant role in DNA repair, but a synergistic impact on checkpoint control [52, 53]. During meiosis, the Pph3– Psy2 complex facilitates early stage crossover and centromere pairing by dephosphorylating Zip1(a chromosomal protein in the synaptonemal complex) [54]. Pph3 is also involved in counteracting Mec1 (ATR homolog) in regulating inappropriate telomerase activity at DNA lesions [55]. Mec1 inhibits de novo telomere formation at DSBs by phosphorylating Cdc13, a protein essential for a functional telomerase complex. Pph3 dephosphorylates Cdc13 which enhances its accumulation at DSBs and allows cells to tolerate irreparable DSBs [55]. A PP4 complex also counters the ATR-CHK1 pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos, and prevents DNA damage-dependent delays during early development [56]. Currently, it is unclear whether these newly discovered functions of PP4 are conserved in metazoans.

PP6

PP6 is also classified as a PP2A-like phosphatase based on homology to the catalytic subunit of PP2A [57]. Human PP6 was identified by its ability to rescue temperature sensitive Sit4 (sit4ts) mutants, the homolog of PP6 in S. cerevisiae [58]. PP6 forms heterotrimeric complexes with regulatory subunits (PP6R1, R2, R3) containing the conserved SAPS (Sit4-associated protein subunits) domain [59], and proteins with ankyrin repeat domains (ANKRD) [60]. Like other PP2A-like phosphatases, depletion of the PP6C–R1 complex correlates with increases in levels of γ–H2AX [61]. Recent studies have shown that PP6 activates DNA-PK after IR [57, 61], but the molecular mechanism remains contentious. DNA damage-induced, and DNA-PK-dependent, accumulation of a PP6C–R1 complex in the nucleus has been reported to enhance its interaction with DNA-PK [57]. By contrast, the association of DNA-PK and the PP6 complex has been described as being independent of DNA damage [61]. The reason for this apparent discrepancy is not clear and whether PP6-mediated dephosphorylation of specific DNA-PK residues enhances the enzymatic activity of DNA-PK remains to be determined.

PP5

Owing to its low basal activity, PP5 was identified much later than the other members of the PPP family of Ser/Thr phosphatases [62]. PP5 interacts with ATM [63] and DNA-PK [64], and impacts their activity in contrasting fashion. Whereas ATM signaling is enhanced by the presence of PP5 [63, 65], DNA-PK activity is attenuated by PP5-mediated dephosphorylation of specific phosphoresidues [64]. The ATR signaling pathway is also augmented by PP5 [66, 67]. Intriguingly, the impact of PP2A on ATM and DNA-PK is diametrically opposed to PP5. Both PP2A and PP6C boost the catalytic activity of DNA-PK [26, 57, 61], but PP2A de-phosphorylates ATM, and suppresses its damage-induced activation [23]. Given that the PI3-like kinases have overlapping roles in DSB-induced signaling, it is feasible that phosphatases (such as PP5, PP2A and PP6) coordinate their roles and delineate their substrate specificity. In response to DNA damage PP5 interacts and de-phosphorylates p53 binding protein 1 (53BP1) and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) [68, 69]. PP5-mediated dephosphorylation of PARP1 activates its enzymatic activity, but the physiological relevance of this observation remains unknown. Investigating the dynamics of 53BP1 phosphorylation is even more challenging due to our limited understanding of the combinatorial role of the large number (>40) of phosphoresidues [70, 71].

WIP1

Wild-type p53-induced phosphatase 1 (WIP1) is one of the 18 PP2C genes that are included in the PPM family [72]. Also called PP2Cδ or PPM1D, WIP1 is a monomeric Mg2+- or Mn2+-dependent enzyme. In early studies, the p53-dependent induction of WIP1 after DNA damage suggested a direct role in the DDR [73]. As anticipated, WIP1 dephosphorylates several repair proteins including ATM, p53, CHK1, CHK2, MDM2, and p38 [74-78]. WIP1 dephosphorylates p53 at Ser15 and MDM2 at Ser395, events that destabilize p53 and promote its proteolysis by MDM2 [76]. Dephosphorylation and regulation of ATM activity by WIP remains a contentious issue. In the course of establishing CHK1 and p53 as bona fide WIP1 targets, it was shown that ATM activity and phosphorylation state is not altered by silencing WIP1. More recently, however, WIP1 was found to interact and dephosphorylate ATM [77, 78]. WIP1 also dephosphorylates γ-H2AX, inhibits the G2/M checkpoint and suppresses both HR- and NHEJ-mediated DSB repair [73, 79, 80]. Turning off DDR at the optimal time may be as crucial as turning it on, and collectively these studies suggest that WIP1 is a major player in this critical step of the DDR. Consistent with its well-defined role in de-activating tumor suppressors, WIP1 is an oncogene that is amplified and overexpressed in a variety of human cancers [81, 82].

Identifying DNA repair factors regulated by Ser/Thr Phosphatases

The human genome encodes 518 protein kinases, with 428 known or predicted to phosphorylate serine and threonine residues. By contrast, there are only ∼147 human phosphatase catalytic subunits, of which only 40 are potential Ser/Thr phosphatases [11]. Therefore it is fair to assume that each Ser/Thr phosphatase has a large number of substrates, including DNA repair proteins. Dephosphorylation of DNA repair proteins is typically studied using a candidate-based approach where the repair protein is used as a probe in vitro or in cells to identify the phosphatases that regulate its phosphorylation status. A comprehensive identification of proteins that undergo dephosphorylation during the course of the DDR by any individual phosphatase has not been conducted. In fact, there are limited examples in the literature where a systematic genome-wide method has been utilized to identify proteins dephosphorylated by an individual Ser/Thr phosphatase.

Consensus targeting motif

A consensus targeting motif-based search was utilized to identify substrates of PP1C. Structural analysis of PP1-interacting proteins and sequence alignment revealed a PP1C-binding motif, RVxF, with the consensus sequence K/R [X]0-1 V/I X F/W [83]. One hundred fifteen novel PIPs were discovered by in silico screening using all-against-all BLASTP analysis based on the RVxF motif. This was followed by interaction-mediated validation [84]. Intriguingly, around two-thirds of all PIPs harbor the RVxF motif, including a large number of proteins involved in the DDR, such as BRCA1, Repo-Man, minichromosome maintenance complex component 7 (MCM7), cell division control 25 (CDC25), (PP1 nuclear targeting subunit) PNUTS, retinoblastoma 1 (RB), growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible (GADD)34, 53BP2, and NIMA (never in mitosis gene a)-related kinase 2 (NEK2) [9, 10]. Recently, KAP1 was identified as a PP1 substrate, based on the presence of the RVxF motif [18]. In addition, there are other PP1 binding motifs that are found in a few PIPs, such as the SILK motif (consensus sequence: G/SILR/K) and the MyPhoNE motif [84]. Unfortunately, the binding motifs for other Ser/Thr phosphatases are largely unknown, except for HEAT (Huntingtin's, elongation factor 3 [EF3], A subunit of PP2A and TOR), a helical repeat motif in the A subunit and B56 regulatory subunit of PP2A [85], and in the SAPS domain of PP6 regulatory subunits [86]. Interestingly, all PI3-like kinases possess HEAT repeats in their non-kinase regions [60]. Useful not only for discovering new substrates and functions of a phosphatase catalytic subunit, binding/targeting motifs could also have therapeutic implications. Whereas inhibiting a phosphatase catalytic subunit has a profound non-specific impact on cell health, selective disruption of the interaction between a substrate and the catalytic subunit might have clinical relevance. For example, disrupting the BRCA1–PP1 interaction via targeting the RVxF motif on BRCA1 induces HR-deficiency, and HR-deficient breast/ovarian tumors are being clinically targeted by PARP inhibitors [87]. A small molecule targeting the RVxF motif might sensitize tumors to PARP inhibitors. Therefore a systematic search for binding motifs for all phosphatase catalytic subunits is of paramount importance.

Interaction-based approaches

Identification of protein complexes that associate with a phosphatase has been used to discover substrates of the phosphatase. Typically a multi-tagged version of the phosphatase is overexpressed in cells, and a combination of tandem affinity purification (TAP) and mass spectrometry (MS) is used to isolate and identify specific protein complexes that associate with the phosphatase under different signaling or stress conditions. This approach has successfully identified substrates of WIP1 (e.g. H2AX [70]) that are involved in the DDR. CHK1 was also identified as a protein targeted by WIP1 by virtue of its co-purification with a WIP1-associated complex [77]. Interestingly, in the same study the authors observed that WIP1 dephosphorylates p53, but their TAP/MS analysis did not reveal p53 as a WIP1-associated protein. It is noteworthy that WIP1 is a monomeric enzyme, and proteins that interact directly with WIP1 have a high likelihood of being substrates. In the case of PP2A-like phosphatases, which function as hetero-dimeric/trimeric complexes, the substrates would be expected to directly associate with the regulatory subunits [88]. This additional layer of regulation significantly adds to the complexity. This approach typically yields a long list of interacting proteins, and a very small number of these are hyper-phosphorylated in the absence of the catalytic subunit. The success of a substrate-identification strategy depends on the biochemical, structural and functional properties of each individual phosphatase.

Phosphoproteomic approaches

A universal strategy for capturing phosphatase substrates may be derived from recent advances in phosphoproteomic approaches. The rationale behind these methods is that in the absence of the phosphatase there would be significant increases in the phosphorylated form of the substrates. The critical rate-limiting step is the quantitative capture and analysis of differentially phosphorylated proteins. To identify PP1C substrates, mouse testes homogenate was analyzed by 2-dimensional electrophoresis (2DE), and protein spots showing differential migration patterns were investigated to identify putative substrates [89]. This strategy was limited by the sensitivity of the 2DE step, and provided a very short list of putative substrates. In a more global approach, quantitative phosphoproteomic changes in tyrosine, serine and threonine phosphorylation were profiled in a systems-wide manner in Drosophila cells lacking the tyrosine phosphatase, Ptp61F [90]. Phosphatase-proficient and -deficient cells were differentially labeled using stable isotope labeling by amino acids (SILAC), and the phosphopeptides captured using titanium dioxide (TiO2)-based affinity columns. This study measured the net effect of silencing Ptp61F on the entire signaling network and did not define specific phosphatase–substrate relationships. The data derived from this method, however, can be further dissected in follow-up experiments to identify the direct targets of Ptp61F. This combinatorial strategy of global phosphoproteomic analysis in phosphatase-depleted cells can be further refined at multiple steps to identify phosphatase substrates in the DDR. For example, instead of SILAC, iTRAQ (a new class of isobaric labeling reagents) can be utilized to label four different samples simultaneously, thereby labeling samples which have been exposed to DNA damage in the presence or absence of a phosphatase [91]. It is worth noting, however, that it is not clear whether TiO2-based columns are optimal for quantitative capture of phosphopeptides [92]. Other methods, such as immobilized metal affinity columns (IMAC) with Fe (III) and Ga (III) have been further improved in recent years for large-scale phosphoproteomic applications [93]. A recent study utilized IMAC to capture phosphopeptides enriched in response to DNA damage in the absence of PP5 catalytic activity [94]. Although the rationale for this study was well-founded, there was limited validation of the novel PP5 substrates, and none of the known PP5 substrates involved in the DDR emerged from the screen. Significant progress in phosphoproteomic methods and increased interest in the role of phosphatases in the DDR should propel this field in the near future.

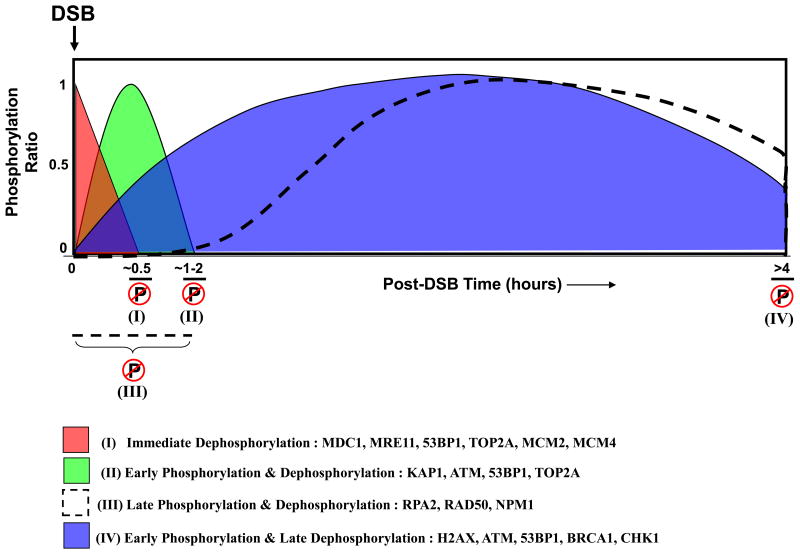

Role of phosphatases in regulating the kinetics of phosphorylation in the DDR

Prior to the emergence of quantitative phosphoproteomics, the traditional view of DSB-induced phospho-signaling was that DSBs initiated a single burst of phosphorylation that was primarily responsible for up-regulating checkpoints. In the course of repair, the phosphorylation gradually dissipates allowing cells to resume cycling. Work in recent years has clearly demonstrated that the DSB-induced signaling cascade is far more complicated, with dynamic cycles of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Several DNA repair factors have multiple phospho-sites that are phosphorylated and dephosphorylated concurrently, and the kinetics are potentially controlled by a combination of kinases and phosphatases working in tandem. We envisage a simplified scenario (Figure 2) wherein phosphatases are potentially required at several key steps in the repair process. The rapid dephosphorylation that occurs within minutes of DNA damage suggests that phosphatases might play a primary role in initiating repair. Important DNA repair factors (such as MDC1) that are constitutively phosphorylated at specific residues might need to be dephosphorylated for recruitment to DSB foci, or for interaction with other repair proteins (Figure 2, I).

Figure 2. Model depicting the putative role of phosphatases in the phospho-dynamics of DSB signaling.

DSBs set off a cascade of precisely timed phosphorylation/dephosphorylation events. These changes are broadly classified in the schematic with examples of repair proteins representing each phase. Few proteins fall into multiple categories because different residues on the same protein become phosphorylated/dephosphorylated at different times after DNA damage. Within minutes of DNA damage, phosphatases target a set of constitutively phosphorylated proteins potentially facilitating the initiation of DNA repair (I). Several DNA repair proteins harbor residues that have detectable phosphorylation very early in the DDR, and they also become dephosphorylated rapidly. There is limited understanding of the physiological significance of this rapid cycle of phosphorylation (II). Although they have consensus kinase targeting motifs (such as S/TQ), some DNA repair proteins have detectable phosphorylation only hours after DNA damage. We speculate that phosphatases play a role in keeping these proteins unphosphorylated early in the damage response (III). Several DNA repair and checkpoint proteins are phosphorylated early in the damage response, and this phosphorylation persists for several hours. Some of these phosphorylation events facilitate repair because cell division is blocked. Phosphatases release the checkpoints and allow cells to resume cycling (IV). On the y axis, maximal phosphorylation of each phosphopeptide is indicated as 1; the x axis represents time. The dephosphorylation of DNA repair factors shown in the figure have been recently described [7, 8, 47].

denotes dephosphorylation via phosphatases.

denotes dephosphorylation via phosphatases.

A subset of proteins undergoes phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events within the first few hours after DNA damage (Figure 2, II). The physiological significance of these phosphorylation events remains largely unknown, thus compounding the problem of elucidating the role of phosphatases in dephosphorylating these proteins. There is an exponentially growing list of proteins that appear to get recruited to sites of DNA damage. It is difficult to conceive how all these factors are spatially accommodated within the proximity of the DSB, but it is feasible that a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle regulates the sequential recruitment and release of factors from the repair sites. Such a process would allow a finite set of repair proteins to be localized at the DSB site at specific stages of the repair process, and these stages could be chronologically defined after initiation of the phospho-signaling cascade.

Phosphorylation of several repair proteins is detected relatively late in the repair process. Considering that these proteins have consensus phosphorylation motifs (such as S/TQ), and that kinases are active within minutes after the formation of DSBs, it is intriguing to note that these repair proteins are not phosphorylated immediately after damage (Figure 2, III). Two questions emerge from this finding: (i) How are these proteins ‘protected’ from the initial wave of phosphorylation?; and (ii) Is the precise timing of phosphorylation of specific proteins (and even precise residues) important for efficient repair of DSBs? We speculate that temporal regulation of the phosphorylation status of repair factors might be critical for the repair process, and phosphatases could play a role in this step. Some credence for this idea comes from recent work [47] demonstrating that a PP4 complex dephosphorylates RPA2, and maintains the hypophosphorylated form of RPA2 immediately after DNA damage. Using phosphomimetic mutants, or PP4-silenced cells, premature phosphorylation of specific RPA2 residues was observed to impede HR-mediated repair of DSBs, and enhance sensitivity to DNA damaging agents. Why are the kinetics of RPA2 phosphorylation critical for the HR pathway? For efficient HR-mediated repair, the RPA complex must be loaded rapidly onto ssDNA generated at the DSB site [95]. There is delayed formation of chromatinized RPA2 foci in PP4-silenced cells or cells expressing RPA2 phosphomimic mutants. This is consistent with in vitro studies showing that hyperphosphorylated RPA2 competes with ssDNA to bind the basic DNA binding domain of RPA1, thereby impeding the DNA binding ability of the RPA complex [96, 97]. Alternatively, increased association of hyperphosphorylated RPA2 with DNA repair factors [98] prior to foci formation might also impede the process. This is evident from the fact that hyperphosphorylated RPA2 retained in the nuclear soluble fraction sequesters RAD51 preventing its recruitment to DSB sites and further impairing the DSB repair process. This study supports the hypothesis that phosphatases regulate the timing of a phosphorylation event and that this is important for efficient repair of DSBs. Finally, the role of phosphatases in the regulation of checkpoints in the DDR has been well characterized, and the dephosphorylation of proteins in the early or late phosphorylation cycle may allow cells to directly release from different cellular checkpoints (Figure 2, IV).

Concluding remarks

A key issue that has not been comprehensively addressed is how phosphatases are regulated in the context of DNA damage. Although there is a large body of information regarding post-translational control of phosphatases [21, 85], there is very limited understanding of modifications that are induced by DSBs. Large scale phosphoproteomic analysis [1, 99] has revealed that regulatory subunits of PP2A/PP1 and catalytic subunits of PP1 are phosphorylated in response to DSBs, but the functional implications of these modifications have not been investigated. As we continue to discover new roles of phosphatases in the DDR, it is imperative to study their changes (e.g. sub-cellular localization, covalent modifications, induction/degradation, etc.) in response to DSBs. Considering the small number of phosphatases, it is counter-intuitive that they should have such overlapping roles. For example, γ-H2AX is dephosphorylated by the PP2A-like phosphatases and by WIP. Why do cells have more than one phosphatase for the Ser139 residue of H2AX? We speculate that each phosphatase works on γ-H2AX or other DNA repair substrates in different locations (i.e. ‘on’ or ‘off’ chromatin), during different time periods after DNA damage (early versus late), and in response to different types of DNA damage. More systematic and global approaches are necessary to understand the interplay of phosphatases, both with each other and with the kinases.

Acknowledgments

DC is by R01CA142698 (NCI), JCRT and a Barr Award. DL was supported by NIH-training grant (CA 009078-34). We apologize to our colleagues whose work we could not discuss due to space constraints.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Matsuoka S, et al. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mu JJ, et al. A proteomic analysis of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM)/ATM-Rad3-related (ATR) substrates identifies the ubiquitin-proteasome system as a regulator for DNA damage checkpoints. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17330–17334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinhardt HC, Yaffe MB. Kinases that control the cell cycle in response to DNA damage: Chk1, Chk2, and MK2. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith J, et al. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;108:73–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380888-2.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Vugt MA, et al. Polo-like kinase-1 controls recovery from a G2 DNA damage-induced arrest in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2004;15:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takaki T, et al. Polo-like kinase 1 reaches beyond mitosis--cytokinesis, DNA damage response, and development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:650–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennetzen MV, et al. Site-specific phosphorylation dynamics of the nuclear proteome during the DNA damage response. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1314–1323. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900616-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bensimon A, et al. ATM-dependent and -independent dynamics of the nuclear phosphoproteome after DNA damage. Sci Signal. 2010;3:rs3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bollen M, et al. The extended PP1 toolkit: designed to create specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuntziger T, et al. Protein phosphatase 1 regulators in DNA damage signaling. Cell Cycle. 2011;10 doi: 10.4161/cc.10.9.15442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moorhead GB, et al. Emerging roles of nuclear protein phosphatases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:234–244. doi: 10.1038/nrm2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng A, et al. Repo-man controls a protein phosphatase 1-dependent threshold for DNA damage checkpoint activation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter SL, et al. The interaction of PP1 with BRCA1 and analysis of their expression in breast tumors. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu YM, et al. A PP1-binding motif present in BRCA1 plays a role in its DNA repair function. Int J Biol Sci. 2008;4:352–361. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazzi M, et al. Dephosphorylation of gamma H2A by Glc7/protein phosphatase 1 promotes recovery from inhibition of DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:131–145. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01000-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.den Elzen NR, O'Connell MJ. Recovery from DNA damage checkpoint arrest by PP1-mediated inhibition of Chk1. Embo J. 2004;23:908–918. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada M, et al. Protein phosphatase 1gamma is responsible for dephosphorylation of histone H3 at Thr 11 after DNA damage. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:883–889. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, et al. SUMOylation of the transcriptional co-repressor KAP1 is regulated by the serine and threonine phosphatase PP1. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra32. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honkanen RE, Golden T. Regulators of serine/threonine protein phosphatases at the dawn of a clinical era? Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:2055–2075. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Hoof C, Goris J. Phosphatases in apoptosis: to be or not to be, PP2A is in the heart of the question. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1640:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssens V, et al. PP2A holoenzyme assembly: in cauda venenum (the sting is in the tail) Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westermarck J, Hahn WC. Multiple pathways regulated by the tumor suppressor PP2A in transformation. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodarzi AA, et al. Autophosphorylation of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated is regulated by protein phosphatase 2A. Embo J. 2004;23:4451–4461. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li G, et al. Phosphatase type 2A-dependent and -independent pathways for ATR phosphorylation of Chk1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7287–7298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen P, et al. Protein phosphatase 2A antagonizes ATM and ATR in a Cdk2- and Cdc7-independent DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1997–2011. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1997-2011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas P, et al. Protein phosphatases regulate DNA-dependent protein kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18992–18998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman AK, et al. Negative regulation of CHK2 activity by protein phosphatase 2A is modulated by DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:736–747. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung-Pineda V, et al. Phosphorylation of Chk1 by ATR is antagonized by a Chk1-regulated protein phosphatase 2A circuit. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7529–7538. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00447-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang X, et al. Protein phosphatase 2A interacts with Chk2 and regulates phosphorylation at Thr-68 after cisplatin treatment of human ovarian cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:703–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan Y, et al. Protein phosphatase 2A has an essential role in the activation of gamma-irradiation-induced G2/M checkpoint response. Oncogene. 2010;29:4317–4329. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dozier C, et al. Regulation of Chk2 phosphorylation by interaction with protein phosphatase 2A via its B′ regulatory subunit. Biol Cell. 2004;96:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chowdhury D, et al. gamma-H2AX dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A facilitates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2005;20:801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakada S, et al. PP4 is a gamma H2AX phosphatase required for recovery from the DNA damage checkpoint. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1019–1026. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q, et al. A nonhomologous end-joining pathway is required for protein phosphatase 2A promotion of DNA double-strand break repair. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1012–1021. doi: 10.1593/neo.09720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacLaine NJ, Hupp TR. How phosphorylation controls p53. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:916–921. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.6.15076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dohoney KM, et al. Phosphorylation of p53 at serine 37 is important for transcriptional activity and regulation in response to DNA damage. Oncogene. 2004;23:49–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shouse GP, et al. Serine 15 phosphorylation of p53 directs its interaction with B56gamma and the tumor suppressor activity of B56gamma-specific protein phosphatase 2A. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:448–456. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00983-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li HH, et al. A specific PP2A regulatory subunit, B56gamma, mediates DNA damage-induced dephosphorylation of p53 at Thr55. Embo J. 2007;26:402–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shouse GP, et al. ATM-mediated phosphorylation activates the tumor-suppressive function of B56gamma-PP2A. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen GI, et al. PP4R4/KIAA1622 forms a novel stable cytosolic complex with phosphoprotein phosphatase 4. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29273–29284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803443200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen PT, et al. Protein phosphatase 4--from obscurity to vital functions. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3278–3286. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Williams GT. Protein phosphatase 4 regulates apoptosis, proliferation and mutation rate of human cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1490–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mourtada-Maarabouni M, Williams GT. Protein phosphatase 4 regulates apoptosis in leukemic and primary human T-cells. Leuk Res. 2009;33:1539–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, et al. Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) activity is regulated by interaction with protein serine/threonine phosphatase 4. Genes Dev. 2005;19:827–839. doi: 10.1101/gad.1286005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chowdhury D, et al. A PP4-phosphatase complex dephosphorylates gamma-H2AX generated during DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2008;31:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee DH, et al. A PP4 phosphatase complex dephosphorylates RPA2 to facilitate DNA repair via homologous recombination. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:365–372. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keogh MC, et al. A phosphatase complex that dephosphorylates gammaH2AX regulates DNA damage checkpoint recovery. Nature. 2006;439:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature04384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guillemain G, et al. Mechanisms of checkpoint kinase Rad53 inactivation after a double-strand break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3378–3389. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00863-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Neill BM, et al. Pph3-Psy2 is a phosphatase complex required for Rad53 dephosphorylation and replication fork restart during recovery from DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9290–9295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703252104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szyjka SJ, et al. Rad53 regulates replication fork restart after DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1906–1920. doi: 10.1101/gad.1660408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Travesa A, et al. Distinct phosphatases mediate the deactivation of the DNA damage checkpoint kinase Rad53. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17123–17130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim JA, et al. Protein phosphatases pph3, ptc2, and ptc3 play redundant roles in DNA double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:507–516. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01168-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Falk JE, et al. A Mec1- and PP4-dependent checkpoint couples centromere pairing to meiotic recombination. Dev Cell. 2010;19:599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang W, Durocher D. De novo telomere formation is suppressed by the Mec1-dependent inhibition of Cdc13 accumulation at DNA breaks. Genes Dev. 2010;24:502–515. doi: 10.1101/gad.1869110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SH, et al. SMK-1/PPH-4.1-mediated silencing of the CHK-1 response to DNA damage in early C. elegans embryos. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:41–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200705182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Mi J, et al. Activation of DNA-PK by ionizing radiation is mediated by protein phosphatase 6. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bastians H, Ponstingl H. The novel human protein serine/threonine phosphatase 6 is a functional homologue of budding yeast Sit4p and fission yeast ppe1, which are involved in cell cycle regulation. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 12):2865–2874. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.12.2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stefansson B, Brautigan DL. Protein phosphatase 6 subunit with conserved Sit4-associated protein domain targets IkappaBepsilon. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22624–22634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perry J, Kleckner N. The ATRs, ATMs, and TORs are giant HEAT repeat proteins. Cell. 2003;112:151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Douglas P, et al. Protein phosphatase 6 interacts with the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit and dephosphorylates gamma-H2AX. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1368–1381. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00741-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen MX, Cohen PT. Activation of protein phosphatase 5 by limited proteolysis or the binding of polyunsaturated fatty acids to the TPR domain. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:136–140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ali A, et al. Requirement of protein phosphatase 5 in DNA-damage-induced ATM activation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:249–254. doi: 10.1101/gad.1176004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wechsler T, et al. DNA-PKcs function regulated specifically by protein phosphatase 5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1247–1252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307765100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yong W, et al. Mice lacking protein phosphatase 5 are defective in ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-mediated cell cycle arrest. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14690–14694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kang Y, et al. Protein phosphatase 5 is necessary for ATR-mediated DNA repair. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404:476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang J, et al. Protein phosphatase 5 is required for ATR-mediated checkpoint activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9910–9919. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.9910-9919.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dong F, et al. Activation of PARP-1 in response to bleomycin depends on the Ku antigen and protein phosphatase 5. Oncogene. 2010;29:2093–2103. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kang Y, et al. Protein phosphatase 5 regulates the function of 53BP1 after neocarzinostatin-induced DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9845–9853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809272200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Vugt MA, et al. A mitotic phosphorylation feedback network connects Cdk1, Plk1, 53BP1, and Chk2 to inactivate the G(2)/M DNA damage checkpoint. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Linding R, et al. Systematic discovery of in vivo phosphorylation networks. Cell. 2007;129:1415–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schweighofer A, et al. Plant PP2C phosphatases: emerging functions in stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Macurek L, et al. Wip1 phosphatase is associated with chromatin and dephosphorylates gammaH2AX to promote checkpoint inhibition. Oncogene. 2010;29:2281–2291. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.An H, et al. LZAP inhibits p38 MAPK (p38) phosphorylation and activity by facilitating p38 association with the wild-type p53 induced phosphatase 1 (WIP1) PLoS One. 2011;6:e16427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fujimoto H, et al. Regulation of the antioncogenic Chk2 kinase by the oncogenic Wip1 phosphatase. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1170–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu X, et al. The Wip1 Phosphatase acts as a gatekeeper in the p53-Mdm2 autoregulatory loop. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lu X, et al. PPM1D dephosphorylates Chk1 and p53 and abrogates cell cycle checkpoints. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1162–1174. doi: 10.1101/gad.1291305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shreeram S, et al. Wip1 phosphatase modulates ATM-dependent signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 2006;23:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cha H, et al. Wip1 directly dephosphorylates gamma-H2AX and attenuates the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4112–4122. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moon SH, et al. Wild-type p53-induced phosphatase 1 dephosphorylates histone variant gamma-H2AX and suppresses DNA double strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12935–12947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bulavin DV, et al. Inactivation of the Wip1 phosphatase inhibits mammary tumorigenesis through p38 MAPK-mediated activation of the p16(Ink4a)-p19(Arf) pathway. Nat Genet. 2004;36:343–350. doi: 10.1038/ng1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu X, et al. The type 2C phosphatase Wip1: an oncogenic regulator of tumor suppressor and DNA damage response pathways. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:123–135. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meiselbach H, et al. Structural analysis of the protein phosphatase 1 docking motif: molecular description of binding specificities identifies interacting proteins. Chem Biol. 2006;13:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hendrickx A, et al. Docking motif-guided mapping of the interactome of protein phosphatase-1. Chem Biol. 2009;16:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Virshup DM, Shenolikar S. From promiscuity to precision: protein phosphatases get a makeover. Mol Cell. 2009;33:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guergnon J, et al. Mapping of protein phosphatase-6 association with its SAPS domain regulatory subunit using a model of helical repeats. BMC Biochem. 2009;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sandhu SK, et al. The Emerging Role of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors in Cancer Treatment. Curr Drug Targets. 2011 doi: 10.2174/138945011798829438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gingras AC, et al. A novel, evolutionarily conserved protein phosphatase complex involved in cisplatin sensitivity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1725–1740. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500231-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Henderson H, et al. New candidate targets of protein phosphatase-1c-gamma-2 in mouse testis revealed by a differential phosphoproteome analysis. Int J Androl. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2010.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hilger M, et al. Systems-wide analysis of a phosphatase knock-down by quantitative proteomics and phosphoproteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1908–1920. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800559-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zieske LR. A perspective on the use of iTRAQ reagent technology for protein complex and profiling studies. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:1501–1508. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bodenmiller B, et al. Reproducible isolation of distinct, overlapping segments of the phosphoproteome. Nat Methods. 2007;4:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ndassa YM, et al. Improved immobilized metal affinity chromatography for large-scale phosphoproteomics applications. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2789–2799. doi: 10.1021/pr0602803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ham BM, et al. Novel Ser/Thr protein phosphatase 5 (PP5) regulated targets during DNA damage identified by proteomics analysis. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:945–953. doi: 10.1021/pr9008207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.San Filippo J, et al. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:229–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.125255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu Y, et al. Modulation of replication protein A function by its hyperphosphorylation-induced conformational change involving DNA binding domain B. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32775–32783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505705200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zou Y, et al. Functions of human replication protein A (RPA): from DNA replication to DNA damage and stress responses. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:267–273. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu X, et al. Preferential localization of hyperphosphorylated replication protein A to double-strand break repair and checkpoint complexes upon DNA damage. Biochem J. 2005;391:473–480. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dephoure N, et al. A quantitative atlas of mitotic phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10762–10767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805139105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Toh GW, et al. Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation of Slx4 stimulates Rad1-Rad10-dependent cleavage of non-homologous DNA tails. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]