Abstract

This study was designed to compare the analgesic effects of butorphanol with those of meloxicam following ovariohysterectomy. Fifteen dogs were premedicated with 0.05 mg/kg body weight (BW) of acepromazine by intramuscular (IM) injection, plus 0.2 mg/kg BW of meloxicam by subcutaneous (SC) injection. Fifteen dogs were premedicated with 0.05 mg/kg BW of Acepromazine, IM, plus 0.2 mg/kg BW of butorphanol, IM. Anesthesia was induced with thiopental, and dogs were maintained on halothane. All pain measurements were performed by 1 experienced individual, blinded to treatment. Pain scores and visual analogue scales (VAS) were performed at 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours postpremedication. An analgesiometer was used to determine the pressure required to produce an active avoidance response to pressure applied at the incision line. Pain scores, VAS, and analgesiometer scores were analyzed by using a generalized estimating equations method. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Animals that received meloxicam demonstrated significantly lower pain scores and VAS than did animals that received butorphanol in the first 12 hours after surgery. Results of this study suggest that meloxicam will produce better postoperative analgesia than will butorphanol.

Mucosal bleeding times were performed on cooperative animals in the study group (11 butorphanol, 13 meloxicam). Bleeding times were performed prior to premedication, 6 hours following premedication, and 24 hours after premedication. The 6- and 24-hour readings were compared with baseline bleeding times by using a paired t-test with a Bonferroni correction (a significance level of P < 0.025). Bleeding times did not change significantly over time.

Introduction

Elective ovariohysterectomy (OHE) is a common procedure in general veterinary practice. It is generally accepted that some degree of postoperative pain will be present. The degree of pain may vary with the amount of trauma to tissue and with the pain threshold of the individual animal. Animals undergoing OHE benefit from intraoperative and postoperative analgesic therapy (1,2,3,4).

Options for analgesia include μ-opiate receptor agonist drugs, such as morphine; κ-opiate receptor agonists, such as butorphanol; and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDS). Opiate drugs will produce effective analgesia during the intra- and postoperative periods. Butorphanol has been commonly used in Canadian veterinary patients for postoperative pain control (5). The duration of action of butorphanol may be quite short (< 1 h) (6). Modern NSAID drugs, such as ketoprofen, will produce effective postoperative analgesia. Ketoprofen is not recommended intraoperatively, due to the risk of hemorrhage (4).

The cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzyme system is responsible for the catalysis of arachadonic acid precursors to prostaglandins and other inflammatory mediators (7). The COX system consists of 2 isoforms, COX-1 and COX-2. Cyclo-oxygenase-1 activity predominates during physiological conditions and is involved in the maintenance of normal renal and platelet function, and in the integrity of the gastric mucosa (7,8). Cyclo-oxygenase-2 is most active when there is inflammation and is responsible for many of the prostaglandins produced during inflammation (7). Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs that derive most of their activity through inhibition of the COX-2 isoform may be able to produce analgesic and antiinflammatory activity, without adverse effects on renal, gastric, or platelet function (7,8,9).

Meloxicam has been shown to have a COX-1:COX-2 selectivity of 3-77:1, depending on the study (10). Meloxicam has been administered intraoperatively in humans and has the potential to produce preemptive analgesia, it has longer duration of activity than the commonly used opiates. This could result in decreased frequency of administration and potentially superior analgesia. Butorphanol is a κ-opiate agonist commonly used in practice for intra- and postoperative analgesia. In 1996, a survey of veterinarians in Canada revealed that butorphanol was the analgesic of choice for use in dogs (5). The median dose reported in this study was 0.25 mg/kg bodyweight (BW) (5). A recent study compared the analgesic efficacy of meloxicam, ketoprofen, and butorphanol in dogs undergoing abdominal surgery performed by veterinary students (3). The study demonstrated that meloxicam provided superior analgesia, compared with butorphanol, in these study animals. Ovariohysterectomy is probably the most frequently performed surgical procedure in companion animal practice (1). The following study was designed to compare the analgesic efficacy of butorphanol with that of meloxicam in healthy dogs following elective OHE.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Animal Care Committee. Animals enrolled in the study were healthy dogs less than 6 y of age that demonstrated no abnormalities on physical examination, and had a normal packed cell volume (0.38 to 0.55 L/L) and total protein (57 to 80 g/L) values. Animals were fasted for 12 h prior to surgery and admitted to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital (VTH) on the morning of surgery.

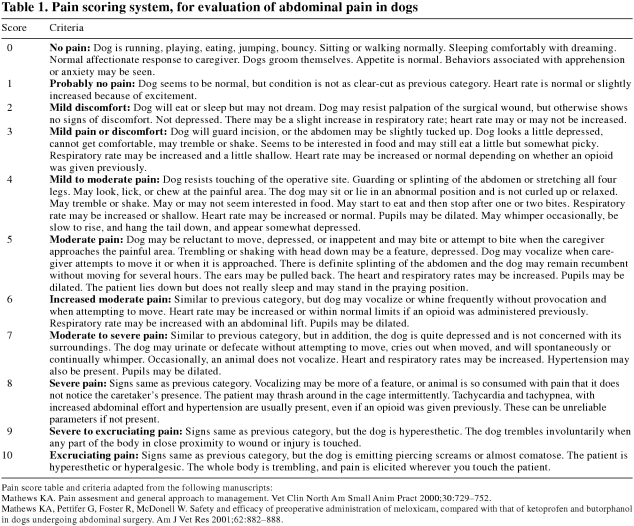

Prior to premedication, animals were observed so that pain and visual analogue scales (VAS) could be recorded. None of the animals used in the study demonstrated any indication of preexisting pain, and all were assigned a pain and VAS of 0. Pain scores were performed by using a descriptive scale (Table 1). Visual analogue scores were performed by using a standard technique (11). A 100-mm line was used, 0 mm represented no pain, and 100 mm represented the worst possible pain. The observer placed a mark on the line corresponding to the level of pain perceived to be experienced by the animal and the resulting length was used to determine the VAS. An analgesiometer (9) was used to measure the pain threshold by applying pressure around the ventral midline of the abdomen. This reading was taken as the baseline pain threshold.

Table 1.

Animals were randomly allocated, via coin toss, into 2 treatment groups. Group A (15 animals) were premedicated with 0.05 mg/kg BW of acepromazine (Atravet; Ayerst, Montreal, Quebec), IM, and 0.2 mg/kg BW of meloxicam (Metacam; Boehringer-Ingleheim, Burlington, Ontario), SC. Thirty minutes after premedication, these animals were induced to anesthesia with approximately 10 mg/kg BW of thiopental (Pentothal; Abbot Laboratories, Montreal, Quebec), IV, and maintained on halothane (Halothane BP; MTC Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, Ontario) in oxygen. Group B (15 animals) received 0.05 mg/kg BW of acepromazine, IM, and 0.2 mg/kg BW of butorphanol (Torbugesic; Ayerst laboratories, St Laurent, Quebec), IM. These animals were induced to anesthesia with approximately 10 mg/kg BW of thiopental, IV, and maintained on halothane in oxygen.

All surgical procedures were performed by experienced surgeons, 1 faculty member and 1 senior resident. Lactated Ringer's solution was administered, IV, at a rate of 10 mL/kg BW/h. Systolic blood pressure and heart rate were measured and recorded, at 5-min intervals, with either a doppler and cuff technique or an oscillometric monitor (Vet BP/plus 6500; Heska Corporation, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA).

Once a dog was awake it was maintained in the recovery area for observation. All pain measurements were taken by 1 experienced individual (MR), who was blinded to the treatment that had been administered. Pain score and VAS were determined prior to application of the analgesiometer. The analgesiometer was applied at 3 control sites (thorax, radius, and tibia), followed by the surgical site. Specifically, the probe was applied to the wound edge at the center of the incision. The probe was applied until the animal demonstrated an active avoidance response, and the maximum pressure was recorded. This value was subtracted from the baseline value to determine the absolute difference in pressure required to elicit an avoidance response. In order to standardize analgesiometer scores, and account for different baselines, the percentage change in pressure was determined. This percentage change in pressure is expressed as the analgesiometer score. All observations were made at 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h postpremedication.

The primary goal of the numerical pain score was to determine if an animal required rescue analgesia. Any animal with a pain score greater than 3 received rescue analgesia in the form of butorphanol at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg BW, IM. Data from these animals, up to the administration of the analgesic, were included in the analysis. The same pain scoring system was used previously for the determination of postoperative pain in dogs, following laparotomy (3).

Mucosal bleeding times were determined on cooperative animals in the study groups (11 butorphanol, 13 meloxicam) prior to premedication, 6 h after premedication, and 24 h after premedication. The 6- and 24-hour readings were compared with baseline bleeding times by means of a paired t-test with Bonferroni's correction. A level of P < 0.025 was taken as significant. Total surgical times were compared with a 2 sample t-test. A level of P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Pain score, VAS, and analgesiometer scores were compared graphically between treatments across sample times. The association between treatment status (meloxicam or control), sample time, and pain score was analyzed by using a generalized estimating equations (GEE) method to account for overdispersion within the data resulting from the repeated measures design. The null hypothesis was that there would be no difference in pain score, VAS, or analgesiometry score between treatment groups in the critical first 12 h following surgery when premedication protocols would be expected to be the most effective. Data were analyzed by using a statistical computer software program (SAS, version 8.02 for Windows (PROC GENMOD); SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Model specifications included a normal distribution, identity link function, repeated statement with subject equal to dog identification, and an autoregressive, or AR(1), correlation structure. Treatment was considered a class variable with 2 categories (meloxicam and butorphanol). Time was also treated as a class variable with 6 categories (2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h postpremedication). Only the variables remaining in the final multivariable model at P < 0.05, based on the robust empirical standard errors produced by the GEE analysis, are reported here.

The main-effects model was assessed for first-order interactions where treatment and time remained in the model with P < 0.05. Only interactions significant at P < 0.05 are reported. Model diagnostics included visual examination of the raw and standardized residuals (12). The residuals were plotted against predicted values of each observation, and the normality of the residuals was assessed with a Wilk Shapiro test. The ratio of the final model deviance to the model degrees of freedom also was examined (12). The modeling process was repeated separately for pain scores, VAS, and analgesiometry scores (12).

Results

Mean surgery time was 27 min (standard deviation (s) = 16 min) for the meloxicam group and 26 min (s = 8 min) for the butorphanol group. The difference was not significant.

Systolic blood pressure ranged from 72 mmHg to 130 mmHg in the butorphanol treatment group, and 75 mmHg to 135 mmHg in the meloxicam treatment group. Heart rate ranged from 45 to 180 beats/min in the butorphanol treatment group, and 52 to 185 beats/min in the meloxicam treatment group.

Time after premedication was significant in all models. There were no significant interactions between time and treatment for any of the models examined.

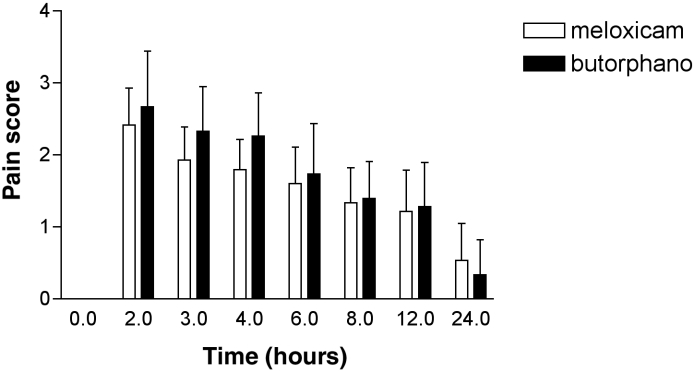

The butorphanol treatment group had a significantly higher pain score (Figure 1) than did the meloxicam treatment group in the first 12 h following surgery (difference = 0.23 [95% CI; 0.01 to 0.45]; P = 0.04).

Figure 1. Pain score: meloxicam 0.2 mg/kg BW + acepromazine 0.05 mg/kg BW, compared with butorphanol 0.2 mg/kg BW + acepromazine 0.05 mg/kg BW. Error bars = s.

s – Standard deviation

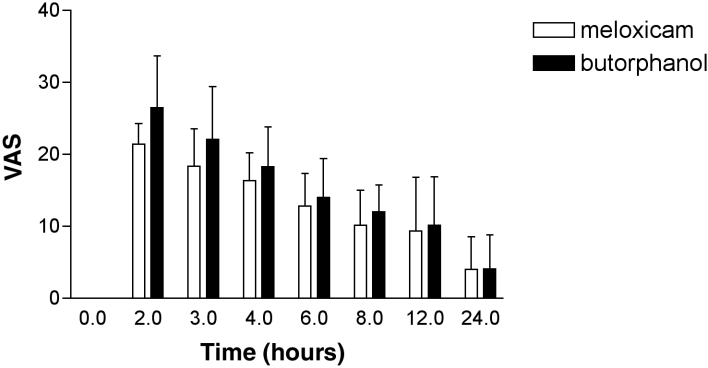

The VAS for pain (Figure 2) for the dogs treated with meloxicam were significantly lower than the VAS for the dogs treated with butorphanol from the time of surgery up to and including 12 h postpremedication (difference = 2.7 [95% CI; 0.1 to 5.4]; P = 0.04).

Figure 2. Visual analogue score (VAS): meloxicam 0.2 mg/kg BW + acepromazine 0.05 mg/kg BW, compared with butorphanol 0.2 mg/kg BW + acepromazine 0.05 mg/kg BW. Error bars = s.

s – Standard deviation

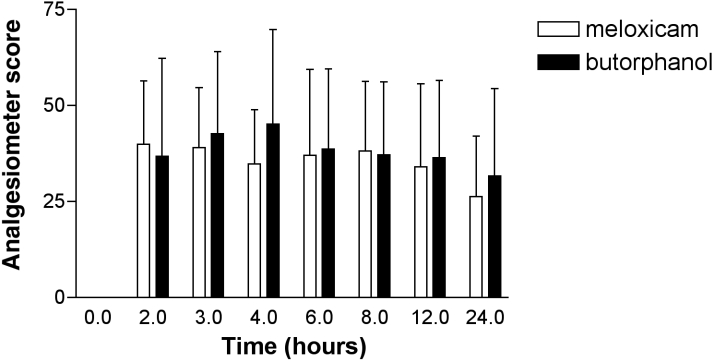

There was no significant difference between the analgesiometry scores (Figure 3) (difference = 33 [95% CI; -94 to 161]; P = 0.60) of the butorphanol and meloxicam treatment groups.

Figure 3. Analgesiometer score: meloxicam 0.2 mg/kg BW + acepromazine 0.05 mg/kg BW, compared with butorphanol 0.2 mg/kg BW + acepromazine 0.05 mg/kg BW. Error bars = s. The analgesiometer score is the percentage decrease in pressure required to produce an active avoidance response at a given time (x), compared to baseline.

s – Standard deviation

Two animals in the butorphanol treatment group (13%) required rescue analgesia. No animal in the meloxicam group required rescue analgesia. One dog required rescue analgesia 3 h after premedication, by 4 h the dog had a pain score of 2. The other dog required rescue analgesia at 2.5 h after premedication; it was still pained at 3 h, so an additional 0.2 mg/kg BW of butorphanol was administered IV. The pain score was 2 or less for the remainder of the monitoring period.

Mucosal bleeding time did not change significantly with either treatment. Mean bleeding times at baseline for meloxicam- and butorphanol-treated dogs were 82 s (s = 24) and 89 s (s = 37), respectively; at 6 h, 88 s (s = 28) and 102 s (s = 40), respectively; and at 24 h, 79 s (s = 18) and 75 s (s = 17), respectively.

Discussion

Results from this study suggest that meloxicam produces superior analgesia to butorphanol at the doses used. Behavioral scores (pain score and VAS) were significantly lower with meloxicam. Analgesiometer readings were somewhat difficult to interpret and considerable individual variation was present. Neither meloxicam nor butorphanol prevented the development of wound hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to application of pressure along the wound edges). The same technique was recently used to compare the analgesic effects of meloxicam and other NSAIDS in cats (9) and in dogs treated with meperidine (13) or carprofen (14). Significant wound hyperalgesia, following ovariohysterectomy, was also noted in these studies (9,13,14). It could be argued that a higher dose of butorphanol would have resulted in improved analgesia. A butorphanol dose of 0.2 to 0.8 mg/kg BW, SC, has been found to be effective for visceral analgesia in the dog (6); duration of analgesia was found to be 23 to 53 min (6). Dogs in the current study required rescue analgesia at 2.5 and 3 h postpremedication. Given the short duration of effect noted in the above study (6), it is not surprising that dogs required rescue analgesia in the immediate postoperative period.

Butorphanol has been shown to be less effective in controlling pain, postlaparotomy, than ketorolac or flunixen (15). In this study, butorphanol was used at a dose of 0.4 mg/kg BW, IM, and only butorphanol-treated dogs required rescue analgesia postlaparotomy (15). Butorphanol did not provide adequate postoperative pain control in dogs that had undergone cystotomy or splenectomy in a teaching laboratory (3). Butorphanol was administered at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg BW, IM, as a premedication, followed by the same dose, IV, at the end of surgery (3). Eleven of 12 dogs required additional analgesia, most soon after extubation, and many dogs required repeated doses of rescue analgesia. It is important to note that the current study used a pain score of 4 to determine if rescue analgesia was required. The quoted study used a pain score of 3 or greater (3). The pain scoring systems used in both studies were quite similar. If a pain score of 3 had been used in the current study, more animals would have to have received rescue analgesia. All of these studies demonstrate that, in dogs, butorphanol does not provide adequate postoperative pain control following a variety of surgical procedures. The current study supports these findings and demonstrates that meloxicam will provide superior analgesia, compared with butorphanol, after routine ovariohysterectomy.

It could be argued that it is not valid to compare a short acting narcotic with a long acting NSAID. This may be a fair comment, and repeat dosing with butorphanol may provide similar analgesia to a single dose of meloxicam. This is probably not practical in most practice situations. Duration of action is not the only factor to consider. In the study quoted above (3), dogs received 0.2 mg/kg BW, IV, of butorphanol at the end of surgery. Most of these animals still required rescue analgesia on extubation. This illustrates that butorphanol, at the quoted dose, was not effective at controlling postoperative pain, even shortly after administration.

Platelet function tends to be preserved with meloxicam. A study in humans (16) demonstrated no change in platelet aggregation, and only a minor prolongation of the closure time following treatment with meloxicam. Closure time is measured with a platelet function analyzer, it measures the time that it takes for a platelet plug to form on a microscopic aperture cut into a membrane (16). In the same study, indomethacin, a preferential COX-1 inhibitor, produced a significant reduction in platelet activation, and a significant prolongation of closure time. The fact that meloxicam did not prolong mucosal bleeding times in the current study suggests that it had minimal effects on platelet function. It would still be wise to exercise caution if blood loss is anticipated from a surgical procedure. These findings are similar to those observed when meloxicam was administered to dogs undergoing cystotomy or splenectomy (3).

One of the perceived advantages of a specific COX-2 inhibitor is that it has less potential to impair renal function and thus may have advantages in the perioperative period. It is important to note that renal function was not measured, and that blood pressure was closely monitored during anesthesia in this study. Most of the animals in the study maintained a systolic pressure > 90 mmHg. Two animals in the butorphanol group and 3 animals in the meloxicam group experienced a drop in systolic pressure to 75–80 mmHg. These drops were transient and resolved quickly. Similar blood pressures were observed in a previous study in which animals were anesthetized for a significantly longer period of time than animals in the current study, and, at necropsy, no renal changes that could be attributed to drug administration were observed (3). There is evidence to suggest that COX-2 inhibitors share the same adverse renal effects as other NSAIDS and that the same cautions should be exercised with COX-2 inhibitors as with COX-1 inhibitors (17). These drugs should not be administered in patients with renal or hepatic disease, dehydration, low effective circulating volume (congestive heart failure, diuretics), coagulopathies, concurrent use of other NSAIDS or corticosteroids, evidence of gastric ulceration, or other gastrointestinal disorders. They are also contraindicated in animals with intervertebral disk disease, in shock, that are hemorrhaging, have asthma, or are pregnant (18).

The major objective of this study was to determine if meloxicam would provide equal or superior analgesia to butorphanol following canine ovariohysterectomy; meloxicam provides superior postoperative analgesia to butorphanol, when the drugs are administered preemptively.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The authors thank AHTs Brenda Beierle, Joan Caulkett, Sharon Martin, Nadine Schueller, Sherry Sutherland, and Jody Walchuk for their assistance with this study. CVJ

This research was funded by Boehringer Inglheim.

Address all correspondence to Dr. Nigel Caulkett; e-mail: nigel.caulkett@usask.ca

Reprints will not be available from the authors.

References

- 1.Fox SM, Mellor DJ, Stafford KJ, Lowoko CRO. The effects of ovariohysterectomy plus different combinations of halothane anaesthesia and butorphanol analgesia on behavior in the bitch. Res Vet Sci 2000;68:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lascalles DB, Cripps PJ, Jones A, Waterman-Pearson AE. Efficacy and kinetics of carprofen, administered preoperatively or postoperatively for the prevention of pain in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Vet Surg 1998;27:568–582. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mathews KA, Pettifer G, Foster R, McDonell W. Safety and efficacy of preoperative administration of meloxicam, compared with that of ketoprofen and butorphanol in dogs undergoing abdominal surgery. Am J Vet Res 2001;62:882–888. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mathews KA. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics: a review of current practice. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2002;12:89–97.

- 5.Dohoo SE, Dohoo IR. Postoperative use of analgesics in dogs and cats by Canadian veterinarians. Can Vet J 1996;37:546:551. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sawyer DC, Rech RH, Durham RA, Adams TA, Richter ME, Striler EL. Dose response to butorphanol administered subcutaneously to increase visceral nociceptive threshold in dogs. Am J Vet Res 1991;52:1826–1830. [PubMed]

- 7.Vane JR, Botting RM. Mechanism of action of aspirin-like drugs. Sem Arth Rheum 1997;26:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Thompson JP, Sharpe P, Kiani S, Owen-Smith O. Effect of meloxicam on postoperative pain after abdominal hysterectomy. Br J Anaesth 2000;84:151–154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Slingsby LS, Waterman-Pearson AE. Postoperative analgesia in the cat after ovariohysterectomy by use of carprofen, ketoprofen, meloxicam or tolfenamic acid. J Small Anim Pract 2000;41:447–450. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hawkey CJ. COX-2 inhibitors. Lancet 1999;353:307–353. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Mathews KA. Pain assesment and general approach to management. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2000;30:729–752. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.SAS Institute Inc., SAS/STAT Software: Changes and enhancements through release 6.12., Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute Inc. 1997.

- 13.Lascalles BD, Cripps PJ, Jones A, Waterman AE. Postoperative hypersensitivity and pain: the pre-emptive value of pethidine for ovariohysterectomy. Pain 1997;73:461–471. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Lascalles BD, Cripps PJ, Jones A, Waterman-Pearson AE. Efficacy and kinetics of carprofen, administered preoperatively or postoperatively for prevention of pain in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Vet Surg 1998;27:568–582. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Matthews KA, Paley DM, Foster RA, Valliant AE, Young SA. A comparison of ketorolac with flunixen, butorphanol, and oxymorphone in controlling postoperative pain in dogs. Can Vet J 1996;37:557–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.De Meijer A, et al. Meloxican 15 mg/day, spares platelet function in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999;66:425–430. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Brater DC. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on renal function: focus on cycloxygenase-2-selective inhibition. Am J Med 1999;107:65S–71S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mathews KA. Indications and contraindications for pain management in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Amer: Small An Pract 2000;30:783–804. [DOI] [PubMed]