Abstract

Angiogenesis and inflammation are important therapeutic targets in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). It is well known that proteolysis mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) promotes angiogenesis and inflammation in the tumor microenvironment. Here, the effects of the MMP-inhibitor TIMP-2 on NSCLC inflammation and angiogenesis were evaluated in TIMP-2 deficient (timp2−/−) mice injected subcutaneously with Lewis-Lung carcinoma cells and compared with the effects on tumors in wild-type (WT) mice. TIMP-2-deficient mice demonstrated increased tumor growth, enhanced expression of angiogenic marker αv β3 in tumor and endothelial cells and significantly higher serum-VEGF-A levels. Tumor-bearing-timp2−/− mice showed a significant number of inflammatory cells in their tumors, upregulation of inflammation mediators, NF-κB and Annexin A1, as well as higher levels of serum IL-6. Phenotypic analysis revealed an increase in myeloid-derived-suppressor-cell (MDSC) cells (CD11b+, Gr-1+) that co-expressed VEGF-R1+ and elevated MMP activation present in tumors and spleens from timp2−/− mice. Furthermore, TIMP-2-deficient tumors up-regulated expression of the immunosuppressing genes controlling MDSC growth, IL-10, IL-13, IL-11, and CCL-5/RANTES, as well as decreased IFN-γ and increased CD40L. Moreover, forced TIMP-2 expression in human lung-adenocarcinoma A-549 resulted in a significant reduction of MDSCs recruited into tumors, as well as suppression of angiogenesis and tumor growth. The increase in MDSCs has been linked to cancer immunosuppression and angiogenesis. Therefore, this study supports TIMP-2 as a negative regulator of MDSCs with important implications for the immunotherapy and /or anti-angiogenic treatment of NSCLC.

Introduction

Tumor hypoxia prompts the release of factors in the tumor microenvironment that promote proteolysis of extracellular matrix (ECM) by matrix-metalloproteases (MMPs) that in turn cleave from tumor and stromal cells angiogenic factors as well as inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Activation of MMPs initiates the cascade of inflammatory and angiogenic pathways1–3, signaling the mobilization of a repertoire of inflammatory cells from the bone marrow that can migrate to tumor sites, secondary lymphoid organs, or other tissues4–6.

Evidence from a variety of studies has shown that a subpopulation of bone marrow (BM) derived cells expressing cell surface antigens of immature myeloid cells (CD11b and Gr-1) are capable of infiltrating the primary tumor and alter the tumor microenvironment, and they appear to be the major inflammatory mediators in tumors7–9. BM derived-immature myeloid cells are comprised of myeloid cell progenitors, and precursors of granulocytes, monocytes and dendritic cells. This heterogeneous myeloid population namely myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) have been clearly associated with tumor promotion and progression. Myeloid-derived-suppressor cells (MDSC) mainly function to attenuate harmful effects of excessive immune stimulation and/or autoimmune responses in many pathological conditions. In cancer, MDSCs are able to suppress anti-tumor immunity by inhibiting T cell effectors and/or suppressing antigen presenting cell functions10–14. In addition, these immature myeloid cells can also promote tumor progression by inducing vascularization. Their recruitment into tumors coincides with the “angiogenic switch”15–17 and release of factors that directly promote tumor angiogenesis. Furthermore, these cells have been shown to differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) that in hypoxic conditions produce type 2 cytokines impairing T-cell functions and antigen presentation by dendritic cells, as well as releasing NO, VEGF and MMPs17,18. Moreover, these inflammatory cells are able to migrate to distant tissues and mobilize inflammatory and angiogenic factors, promoting local angiogenesis. This allows for the formation of a pre-metastatic “niche” that supports the survival and invasion of metastatic tumor cells19–23.

Compelling evidence demonstrates that MDS cells directly promote tumor progression by increasing angiogenesis and the immune tolerance of cancer24. These pro-tumor functions might be in part mediated by their expression of matrix metalloproteases MMPs as reported in mice25,26there by releasing angiogenic factors such as VEGF from the ECM27. However, mechanisms other than MMP activity have been reported. Recent studies in cancer patients demonstrated that these cells produce VEGF and related angiogenic factors and trigger the production of Th-2 cytokines28. MDS cells are now believed responsible for the resistance to anti-angiogenic and tumor immune therapies29,30. Current research efforts are aimed at identifying the mechanisms that control immature myeloid cells with the objective of disrupting or impairing their recruitment by tumors and functions as well. Here, we report for the first time the effects of the endogenous MMP inhibitor TIMP-2 on myeloid inflammatory cell function in non-small cell lung cancer. TIMP-2 is a multifunctional protein, secreted into the extracellular matrix. Our laboratory has reported on the effects of TIMP-2 on angiogenesis of lung cancer31–33, and found that in addition to inhibiting MMPs34, TIMP-2 is also capable of binding integrin receptors and enhancing PTP phosphatase activity, resulting in inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo of lung cancer cells35. Moreover, TIMP-2 blocked endothelial cell response to VEGF stimulation by modulating VEGF-R2 phosphorylation and increasing phosphodiesterase activity in human lung microvascular endothelial cells35. Based on these reported findings in lung cancer, we hypothesize that TIMP-2 could target immature myeloid cells and block their pro-tumor activity and possibly their recruitment into non-small cell lung tumors.

Angiogenesis and inflammation are important therapeutic areas in non-small cell lung cancer. Here, we used a TIMP-2 deficient mouse model to demonstrate TIMP-2 effects on MDSCs associated with angiogenesis, inflammation and growth of mouse Lewis lung carcinoma. We further used human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells with enforced expression of TIMP-2 to examine effect on MDSC infiltration and angiogenesis in tumor xenografts. This study suggests that TIMP-2 is a negative regulator of immature myeloid inflammatory cells and provides for a novel strategy to treat lung cancer.

Results

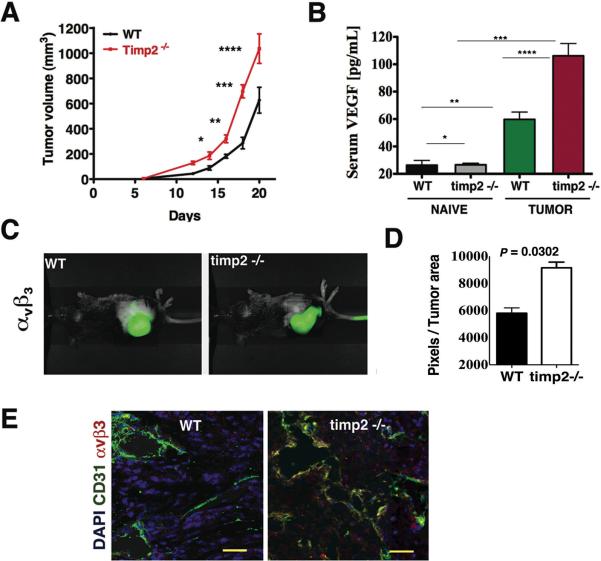

Increased angiogenesis and tumor growth rate in timp2−/− mice

The deficiency of TIMP-2 resulted in a significant increase in the growth rate of Lewis lung carcinoma (LL-2) tumor after day 14 post-injection when compared with tumor growth in wild-type-WT mice (Fig. 1A). Measurement of serum VEGF-A levels in naive, tumor-free mice showed low levels that were not statistical different between WT and timp-2−/− mice (Fig. 1B). In contrast, tumor-bearing mice in either group demonstrated elevated levels of serum VEGF-A as compared with their tumor-free, naive counterparts respectively. However, tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice showed further increase in serum VEGF-A concentration (almost 2-fold, p= 0.004) above levels in tumor bearing-wild type mice (Fig. 1B). The findings suggest that VEGF-A dependent angiogenic pathways are highly activated in tumor-bearing timp-2−/− mice. In an effort to validate these results, we used near-infrared (NIR) in vivo optical imaging to show intra-tumor accumulation of a NIR-tagged probe for integrin αvβ3 (Fig. 1C). Consistent with the elevated serum VEGF-A, expression of αvβ3 was found increased significantly in tumors from timp-2−/− mice compared to those in WT mice (Fig. 1D). In addition, co-localization of integrin αvβ3 and the endothelial cell marker CD31 was clearly increased in tumors from timp2−/− mice compared to tumors in WT mice, indicative of enhanced recruitment of angiogenic blood vessels in TIMP-2-deficient mouse tumors (Fig. 1E). The angiogenic response in non-tumor bearing timp-2−/− mice was also examined using the direct in vivo angiogenesis assay (DIVAA) and VEGF-A stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Unstimulated controls showed similar low levels of angiogenesis. However, with VEGF-A stimulation the angiogenic response increased two-fold in WT mice and three-fold in timp-2−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 1A). We also demonstrated that exogenous TIMP-2 treatment of LL-2 cells blocked MMP-2 activation and decreased significantly the secretion of VEGF-A in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1.

Enhanced angiogenesis and accelerated tumor growth in timp2−/− mice. (A) Growth rate of Lewis lung carcinoma in timp2−/− mice versus tumors in wild-type WT mice (means ± SEM, n =10 in each group, * p=0.007, 14 day, ** p= 0.003, 16 day, ***p=0.002, 18 day, ****p=0.005, 20 day post-injection). (B) VEGF-A serum levels in naive, tumor-free WT versus timp2−/− mice (n=5 in each group, means ± SD *p= n.s.), tumor-bearing WT versus timp2−/− mice (n=10 in each group, means ± SD ****p = 0.0004), naive WT mice versus tumor-bearing WT (n=10 in each group, mean ± SD, **p = 0.004), naive timp2−/− mice versus tumor bearing timp2−/− (n=10, mean ± SD, ***p= 0.0001). (C) Infrared molecular imaging of αvβ3 in LL-2 tumor-bearing WT and timp2−/−mice (D) Accumulated αvβ3 at the tumor site, infrared signal in pixels/tumor area of duplicate experiment (n=4 in each group, mean ± SD). (E) Co-localization of infrared αvβ3 with FITC-CD31 in blood vessels in tumor sections from timp2−/− mice versus tumor in WT mice. Scale bar= 50 μm.

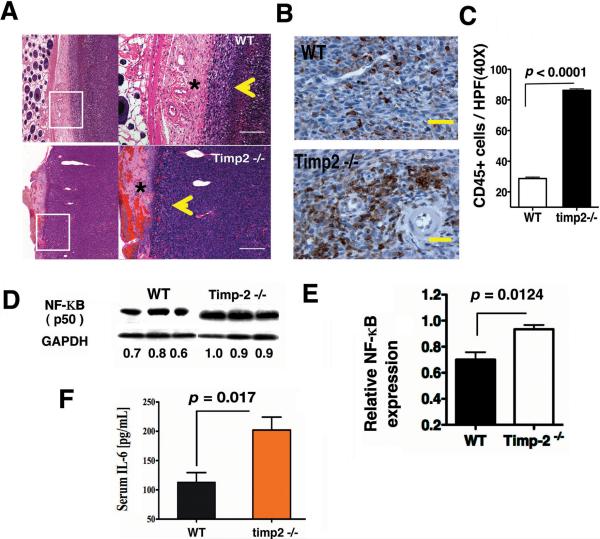

Enhanced inflammation in tumors from timp2−/− mice

Recent studies have correlated increased tumor angiogenesis with inflammatory cell infiltrates. Routine histological examination demonstrated that subcutaneous tumors from timp2−/− mice were more highly vascularized, contained a greater inflammatory infiltrate and tumor cells invaded further into the dermis (Fig. 2A). In addition, timp2−/− sections showed tumor cells together with a significant number of inflammatory cells, and angiogenic vessels (yellow arrowheads) at the invading front as compared with WT tumor sections and the dermis (asterisks) demonstrated leaky blood vessels and edema that were not observed in WT tumor sections (Fig. 2A). These findings prompted us to examine CD45+ leukocyte populations in tumors from both WT and timp2−/− mice. Immunohistochemistry revealed an increase in leukocytes in tumors from timp2−/− mice compared with WT and that these cells showed both a perivascular and diffuse infiltration pattern (Fig. 2B). The number of CD45+ cells per high power field was increased in greater than 50% in timp2−/− tumors (p< 0.0001) as compared with WT tumors (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these results indicate that TIMP-2 deficiency promoted further tumor inflammation.

Figure 2.

Increased inflammation in LL-2 tumor-bearing timp-2−/− mice. (A) Representative H&E of tumor sections from timp2−/− mice demonstrating cancer cells, angiogenic vessels and inflammatory cells invading the dermis (yellow arrowhead) and severe dermis inflammation (*) as compared with tumors in WT mice, scale bar= 100 μm. (B) A representative IHC, CD45+ leukocytes in tumor sections from WT and timp2−/− mice, Scale bar= 50 μm. (C) Number of leukocytes (CD45 brown) per high power field (40×) in tumors from WT and timp2−/−mice (6 fields per tumor section, 4 sections in each group, n= 24, mean ± SD). (D) Western blot, NF-κB p50 expression in tumors from timp2−/− mice versus WT tumor over protein loaded-control GAPDH, integrated densities are shown (E) Relative NF-κB expression in tumors from WT and timp-2−/− mice, duplicate experiment (n = 6 in each group, mean ± SD). (F) Serum IL-6 in tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice versus tumor-bearing WT mice (n=10 in each group, means ± SD).

The critical mediator of inflammation NF-κB has been associated with tumor progression mediated mainly by upregulation of cytokines such as IL-6 as well as angiogenic factors36. To further determine whether inflammation was associated with the enhanced angiogenesis observed in tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice, we analyzed NF-κB p50 levels of expression in tumors from WT and timp2−/− mice. Western blots showed a significant increase of NF-κB in tumors from timp2−/− mice when compared with tumors from WT mice (p = 0.012) (Fig. 2D and E). In addition, tumor-bearing timp2/− mice demonstrated an almost two-fold increase in circulating levels of serum IL-6 (Fig. 2F), suggesting that TIMP-2 deficiency directly contributes to enhance inflammation in tumors.

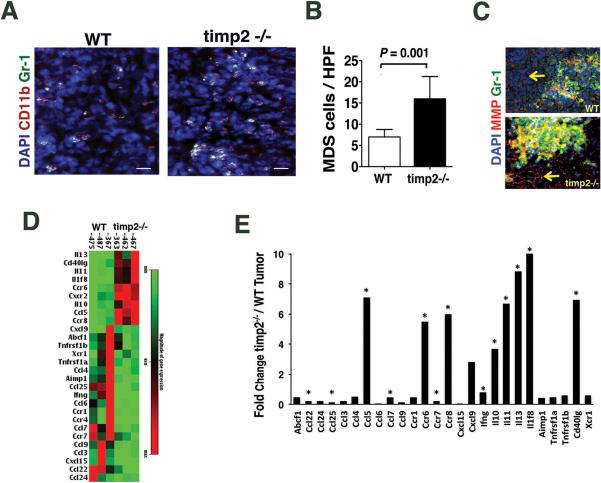

TIMP-2 deficiency increases tumor Gr-1+, CD11b+ cells and immune suppressing factors

We further identified by immune fluorescence staining a fraction of inflammatory cells in tumor sections co-expressing myeloid derived suppressor cell (MDSC) markers, Gr-1 and CD11b (Fig. 3A). While myeloid cells expressing both markers were present in all tumors examined, the number of CD11b+ Gr-1+ cells per high power field were significantly higher (3 times) in tumors from timp2−/− mice compared to the number of MDSCs in tumors from WT mice (Fig. 3B). We also examined matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation in these tumors by analyzing the cleavage of a fluorogenic peptide substrate for MMPs. An intense infrared fluorescence, indicative of an enhanced MMP activation was demonstrated by LL-2 tumor cells from both mice (yellow arrows), and co-localized with inflammatory FITC-Gr-1+ cells (Fig. 3C). However, a high number of FITC-Gr-1+ cells in timp2−/− tumors demonstrated increased MMP activation (Fig. 3C), indicating that the deficiency of the MMP inhibitor (TIMP-2) increase MMP activation, and possibly facilitating the infiltration of a greater number of MDSCs into timp2−/− tumors.

Figure 3.

MDSCs, MMP activity and the profile of inflammatory factors in timp2−/− tumors. (A) Representative tumor sections immune stained for CD11b+, Gr-1+ showing MDSCs (yellow fluorescence) in tumors from WT and timp-2−/− mice, nuclei counter stained with DAPI. Scale bar= 60μm. (B) Number of MDSCs per high power field (20×) in timp2−/− tumors versus WT (4 tumors in each group, n=16, mean ± SD) (C) MMP activation shown as red emission of cleaved infrared-tagged peptide substrate by tumor cells (arrows), MMP activity demonstrated by FITC-Gr-1+ cells in timp2−/− tumors (yellow emission) versus WT tumors, nuclei counter-stained with DAPI. Scale bar= 20 μm. (D) Heat map showing differential gene expression higher than two (> 2) of inflammatory factors tumors from timp-2−/− mice versus WT tumors (n =3 in each groups). (E) Fold change in inflammatory factors from timp2−/− tumors over WT tumors (significant change in three tumors in each group, *p< 0.005).

We further compared the profile of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines expressed in tumors from both TIMP-2 deficient and WT mice using a commercial qRT-PCR array. Expression of cytokine and chemokine genes with fold change higher than two (> 2) was determined in three tumors in each mouse group. Twenty-eight genes were differentially regulated in timp2−/− deficient tumors as compared with WT tumors (Fig. 3D). TIMP-2-deficient tumors demonstrated significant (p < 0.005) increase in the transcription of genes for immunosuppressing cytokines IL-11, IL-13 and IL-10, as well as for chemokine ligands and receptors, CCL-5/RANTES, CXCCR2, CCR8 and 6 along with upregulation of CD40L and downregulation of IFNγ (Fig. 3E). The results revealed that TIMP-2 deficiency elicited immunosuppressing factors that are required for the growth of tumor MDSCs 28,37as well as chemokine receptors such as CCR-8 and CCR-2 expressed by myeloid-derived suppressor cells 38(Fig. 3E). The chemokine CCL-5/RANTES that has been implicated in tumor metastasis 38and CD40L that in a recent report39 was also implicated in immunosuppression mediated by MDSC were all significantly elevated in tumors from timp2−/− mice.

Taken together, these data indicate that TIMP-2 deficiency leads to the increase of inflammatory factors needed for the recruitment and expansion of MDSCs at the tumor site; therefore, the lack of TIMP-2 results in an highly immunosuppressive and angiogenic tumor microenvironment.

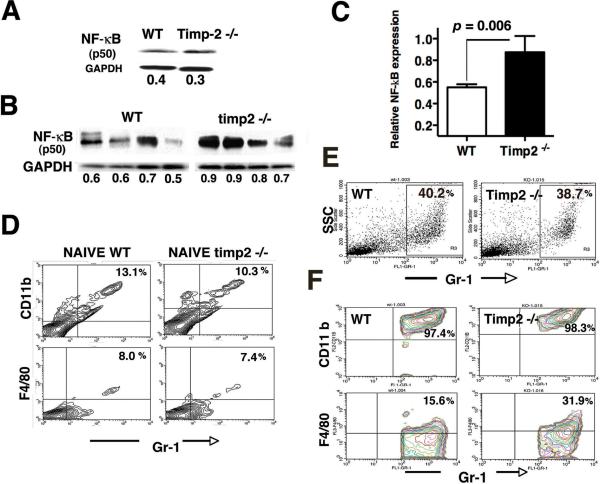

TIMP-2 deficiency and the trafficking of immature CD11b+ Gr-1+ myeloid cells

We investigate further the role of TIMP-2 in inflammation outside primary tumors by evaluating the expression of NF-κB p50 in splenocytes from all mice. Western-blot analysis of spleens from naive, tumor-free WT and timp2−/− mice demonstrated similar low levels of NF-κB p50 expression (Fig. 4A). In contrast to tumor-free mice, elevated NF-κB p50 expression was shown in spleens from tumor-bearing mice. However, spleens from tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice showed a further increase in NF-κB when compared to spleens from tumor-bearing WT mice (Fig. 4B). Quantification by densitometry of NF-κB expression was determined in eight spleens from each mouse group. Results demonstrated a significant upregulation of NF-κB in splenocytes (p=0.006) from tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice (Fig. 4C). This confirms a systemic inflammatory response in tumor-bearing timp2−/− deficient mice that is not limited to the primary tumor site.

Figure 4.

Spleen inflammation and CD11b+ Gr-1+ splenocytes in tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice. (A) NF-κB p50 expression in splenocytes from naive, tumor-free WT and timp2−/− mice over loading control GAPDH, density values shown below (representative Western blot of duplicate analysis) (B) NF-κB p50 expression in four spleens from LL2-tumor bearing mice over GAPDH loading control, integrated intensity values are indicated below. (C) NF-κB p50 expression in spleens from tumor-bearing WT vs. timp2−/− mice (n=8 in each group means ± SD). (D) Total percentage of splenocytes expressing myeloid markers (CD11b, Gr-1, F4/80) in tumor-free, naive mice (representative FACS analysis of duplicate experiments). (E) Representative FACS showing total percentage Gr-1+ splenocytes in spleens from tumor-bearing mice. (F) Co-expression of Gr-1high CD11bhigh and F4/80low by splenocytes (gate Gr-1 vs SSC) from tumor-bearing mice (representative FACS analysis of 2 independent experiments).

Next, we determined whether this systemic inflammatory response indicated by elevated NF-κB in spleens and serum IL-6 levels in tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice was also linked to increased trafficking of immature CD11b+, Gr-1+ myeloid cells. To this aim, splenocytes were isolated from both tumor-free-naive mice and tumor-bearing mice and analyzed by flow cytometry. Splenocytes from tumor-free, naive mice showed similar expression and low percentage of myeloid cells co-expressing CD11b, and Gr-1 as well as the monocyte marker F4/80 (Fig. 4D). In contrast, analysis of gated Gr-1high cell population with variable granularity as indicated by side scatter (SSC) revealed that spleens from both timp2−/− and WT tumor-bearing mice contained a comparable elevation in the percentage of this cell population (Fig. 4E). Further analysis of total Gr-1+ splenocytes in tumor-bearing mice demonstrated increased at the same levels the co-expression of CD11b+ Gr-1+ markers, indicating that tumors induced comparable high percentage of myeloid-derived-suppressor cells in the spleens from both tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 4F). However, a two-fold increase in the percentage of MDSCs with low expression of monocyte F4/80low was detected in spleens from tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice compared with F4/80 expression by MDSCs in WT spleens (Fig. 4F). This might represent a small fraction of monocytic MDSCs in the spleens of tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice. Nevertheless, co-expression of CD11bhigh Gr-1high myeloid markers is consisting with induction by lung tumors of granulocytic MDSCs in spleens from both mice.

Spleens from tumor bearing WT and TIMP-2 deficient mice were also analyzed for TIMP-2 expression. Tumor-bearing WT mice demonstrated co-expression of intracellular TIMP-2 by CD11b+ splenocytes as well as TIMP-2 secreted in the spleen stroma (Supplementary Figure 2A and B). Also, TIMP-2-deficient spleens showed a relatively significant splenomegaly (Supplementary Figure 2C and D). Thus, this increased inflammation in spleens of tumor-bearing TIMP-2- deficient mice confirms a systemic inflammatory response that is not limited to the primary tumor site. Since the spleens from both tumor-bearing timp2−/− and WT mice contained similar number of granulocytic MDSCs, we further analyze MDSCs on their expression of the precursor BM marker VEGF-R1.

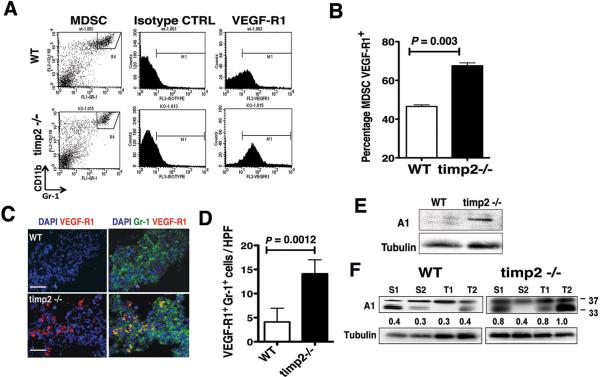

Enhanced expression of VEGF-R1 by MDS cells in tumor-bearing timp-2−/− mice

The receptor for the placental growth factor (VEGF-R1) has been implicated in the functions of inflammatory cells during tumor progression21,40. The release of VEGF-R1+ inflammatory cells from the bone marrow is increased during tumor growth and progression23. Expression of VEGF-R1 by immature myeloid cells has been suggested to enhance invasion and metastasis following their recruitment into tumors21,41. We used flow cytometry to assess the effects of TIMP-2 deficiency on the expression of VEGF-R1 by CD11b+ Gr-1+ immature myeloid cells in spleens of naive and tumor-bearing mice. We found a very low percentage of MDSCs VEGF-R1+ (below 1%) in spleens from both naive, tumor-free timp2−/− and WT mice (data not shown), while a three-color flow cytometric analysis of VEGF-R1 expression by CD11b+ Gr-1+ cells in spleens from tumor-bearing mice demonstrated a higher VEGF-R1 cell surface expression by MDSCs in timp2−/− spleen as compared with expression by MDS cells from tumor-bearing WT mice (Fig. 5A). Analysis of VEGF-R1 expression in the gated MDSC fraction from timp2−/− spleen demonstrated a significant (p= 0.021) increase (60%) as compared with VEGF-R1 expression in gated MDSCs from WT spleens (approximate 42%). This increased VEGF-R1 expression in timp2−/− spleen MDSCs is well above the percentage frequently reported in tumor-bearing mice24. Thus, lung tumor induced significantly the percentage of VEGF-R1+ MDSCs in spleens from TIMP-2 deficient mice (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Increased VEGF-R1+ MDSCs and Annexin A1 in tumor-bearing timp-2−/− mice. (A) A representative FACS analysis of VEGF-R1 expression by CD11b+ Gr-1+ (MDSC, gate R4) splenocytes from tumor-bearing WT and timp2−/− mice. (B) Increased percentage of VEGF-R1+ MDSCs in spleens from tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice versus tumor-bearing WT mice (n=6 spleens in each group, means ± SD). (C) Immune staining of VEGF-R1+ Gr-1+ inflammatory cells in timp2−/− tumor sections versus WT tumors. Scale bar = 20 μm. (D) Number of Gr-1+ VEGF-R1+ cells per high power field (40×) in timp2−/− tumors versus WT tumors (four tumors per group, n=16 hpf per tumor, mean ± SD). (E) Expression of Annexin A in spleens from tumor-free WT versus timp2−/− mice over Tubulin-α protein loading control, integrated density values are shown below. (F) Expression of Annexin A1 (37 kDa) and bioactive peptides in spleens (S) and tumors (T) from tumor bearing WT mice versus timp2−/− mice over loading control Tubulin-α, integrated density values are shown.

We further analyzed tumors for the presence of VEGF-R1+ myeloid cells by immune fluorescence. While tumors in wild-type mice showed a lower number of Gr-1+ VEGFR1+ cells, tumors in timp2−/− deficient mice demonstrated a readily detectable VEGFR1+Gr-1+ cell population (Fig. 5C). Quantitation of the number of Gr-1+ VEGF-R1+ cells (yellow fluorescence) per high power field in four tumor sections in each group demonstrated an increased infiltrate in timp2−/− tumors (Fig. 5D). These findings demonstrated that TIMP-2 deficiency increased the number of systemic VEGF-R1+ MDSCs and favored their recruitment into the primary tumor site.

The Annexin A1 molecule is an inflammation modulator and its N-terminal peptide has been shown to display anti-inflammatory activity in a number of well-established animal models of acute inflammation42. However, in chronic inflammatory conditions, inflammatory cells produce a truncated form of Annexin A1 that is highly inflammatory and that results in increased endothelium transmigration by inflammatory cells43. Moreover, Annexin A1 is upregulated in tumors, and tumor growth is impaired in Annexin A1-deficient mice44–46. Analysis of Annexin A1 expression in spleens of tumor-free naive mice demonstrated a slight up-regulation of intact 37kDa protein in TIMP-2 deficient mice compared with their wild-type littermates (Fig. 5E). In contrast, Western blot analysis of tumor-bearing mice showed elevated expression of Annexin A1 in both spleens and tumors. However, TIMP-2-deficient mice showed up-regulation of intact Annexin A1 (37 kDa) in both spleens and tumors and increase of the truncated Annexin A1 form (33 kDa) in their tumors as compared with WT bearing mice (Fig. 5F). This suggests that TIMP-2 could affect pathways that control expression and processing of Annexin A1 at the primary tumor site, and could potentially regulate endothelium transmigration of VEGF-R1+ MDSCs.

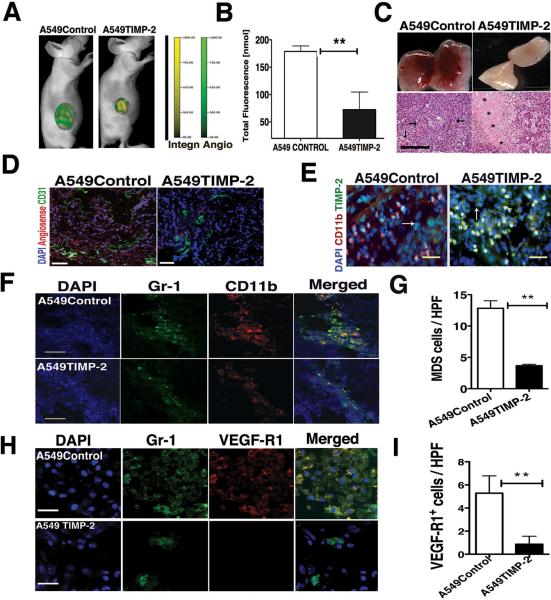

TIMP-2 up-regulation decreases tumor recruitment of MDSCs and blocks angiogenesis

We have previously reported TIMP-2 negative effects on VEGF signal pathway in lung microvascular endothelial cells in vitro35. Conversely, we also demonstrated that the deficiency of TIMP-2 significantly increased the levels of VEGF-A in the serum of tumor-bearing TIMP-2-deficient mice (Fig. 1B).

Now, we sought to determine the involvement of myeloid derived suppressors cells in the anti-tumor effect of TIMP-2 in lung cancer in vivo. To this end, we used retroviral-mediated up-regulation of TIMP-2 into human lung cancer cells A-549 or empty-vector transfected A-549 control cells as previously reported47. First, we confirmed the effects of TIMP-2 on VEGF-R2 in vivo by employing an anti-murine VEGF-R2 antibody incorporated into microbubbles as an ultrasound contrast agent to quantitate total VEGF-R2 expression. Upregulation of TIMP-2 reduced significantly VEGF-R2 in A549TIMP-2 tumor xenografts at day 14 by greater than 75% (p = 0.003) when compared to VEGF-R2 expression in A549Control tumors and this effect correlated with tumor growth (Supplementary Fig. 3A and B). TIMP-2 anti-angiogenic effect was assessed at later times of tumor growth by fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) using infrared-tagged agents Integrinsense targeting αvβ3 and Angiosense for vascular volume (Fig. 6A). Upregulation of TIMP-2 significantly decreased intra tumor concentrations of both indicators of angiogenesis in mice bearing A549TIMP-2 xenografts as compared with mice bearing empty-vector A549Control xenografts (Fig. 6B). Additionally, gross and histological examination of these tumors showed decreased blood vessels as well as areas of necrosis (asterisks) in A549TIMP-2 tumors as compared with A549Control xenografts showing angiogenesis vessels (arrows) (Fig. 6C). Staining of endothelial cells with FITC-CD31antibodies and its co-localization with the fluorescent indicator of angiogenesis (Angiosense) further demonstrated strong TIMP-2 anti-angiogenesis effect in A549TIMP-2 tumors, as a decreased number of blood vessels and low Angiosense were observed compared with A549Control tumors (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

TIMP-2 upregulation decreases tumor MDSCs and angiogenesis. (A) Fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) showing decreased angiogenesis indicators Angiosense (green) and Integrinsense (yellow) in A549TIMP-2 tumor versus Control. (B) Angiogenesis indicators by FMT in A549TIMP-2 xenograft versus Control (n=5 in each group, means ± SD **p=0.002). (C) Gross and H&E show low angiogenesis and tumor necrosis (*) in A549TIMP-2 tumor versus A549Control angiogenic blood vessels (arrows), scale bar= 50 μm. (D) A549TIMP-2 xenograft showing low Angiosense (red) and blood vessels FITC-CD31+ versus Control xenograft, nuclei counterstained with DAPI, scale bar= 50 μm. (E) TIMP-2 in myeloid CD11b+ cells, tumor cells (arrows) and stroma, Scale bar= 20 μm (F) MDSCs in A549TIMP-2 xenograft versus Control xenograft, Scale bar= 50 μm (G) Number of recruited MDSCs per high power field (40×) in tumor sections (n=12 in each group, mean ± SD, ** p< 0.0001). (H) VEGF-R1+ Gr-1+ cells recruited by tumors, scale bar = 20 μm. (I) Number of VEGF-R1+ Gr-1+ cells per high power field (60×) in A549TIMP-2 versus A549Control (n=24 in each group, mean ± SD, ** p< 0.004.

We further determined the expression of TIMP-2 in A549 tumor xenografts. Immune stained sections of A549TIMP-2 xenografts demonstrated elevated intracellular TIMP-2 in tumor and (CD11b+) myeloid cells, as well as TIMP-2 secreted into the tumor stroma as compared with low TIMP-2 expression by both tumor and myeloid cells in A549Control tumors (Fig. 6E). A significant inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activation was previously reported in A549TIMP-2 tumors47. Further analysis of CD11b+ Gr-1+ myeloid cells (yellow fluorescence) demonstrated decreased number of MDSCs in A549TIMP2 xenografts as compared with A549Control xenografts (Fig. 6F), and the quantitation of the number of cells per high power field indicated a significant decrease (p< 0.0001) in the number of infiltrating MDSCs in A549TIMP-2 xenografts as compared with A549Controls (Fig. 6G). Furthermore, A549TIMP-2 tumors also demonstrated significantly fewer VEGF-R1+ Gr-1+ cells as compared with A549Control tumors (Fig. 6H and I). Taken together, these results suggest that TIMP-2 upregulation disrupts the recruitment of MDSCs at the primary tumor site, and interferes of the reported MDSC functions in tumor angiogenesis.

Discussion

It is now widely recognized that inflammatory cells contribute significantly to tumor progression48. The recruitment into tumors of myeloid derived suppressor cells alters the tumor microenvironment and promotes angiogenesis as well as immune suppression13,39. The role of immature myeloid inflammatory cells in angiogenesis and inflammation has been studied in mouse models deficient in matrix metalloproteinases, MMPs. These studies showed that activation of MMPs in the tumor increased angiogenesis mainly by increasing bioavailability of VEGF bound to the extracellular matrix at the initial steps of tumor angiogenesis and subsequent signaling for mobilization of BM inflammatory cells including MDSCs26,49. However, more recent studies have shown that MDSCs produce MMPs and directly promote angiogenesis and tumor immune suppression15,50,49,51. In addition, these studies have shown the pivotal role that VEGF-R1 play in many MDSC functions, including their recruitment by tumors and formation of the pre-metastatic “niche”21,23.

The present study demonstrates the effects of TIMP-2, an inhibitor of MMPs, on the recruitment and function of MDSCs in lung cancer models. The absence of TIMP-2 accelerated tumor growth and stimulated further mediators of angiogenesis and inflammation demonstrated by upregulation of VEGF-A, NF-κB p50, Annexin A1 and IL-6. At the tumor site, the deficiency of TIMP-2 promoted the recruitment of inflammatory cells expressing granulocytic MDSC phenotype and MMP activation along with downregulation of IFNγ, and upregulation of immunossupressing cytokines (IL-10, IL-11 and IL-3) as well as chemokine ligands (CCL-5/RANTES) and their receptors, all known factors required for the recruitment by tumors of MDSCs. In summary, lung tumors deficient in TIMP-2 demonstrated a further increase in angiogenesis and immunosuppression.

We also determined an increase in inflammation mediators NF-κB p50 and Annexin A1 in the spleens from tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice, suggesting a systemic inflammatory response that was not limited to the primary tumor site. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the percentage of MDSCs in the spleens from tumor-bearing timp2−/− mice was not different from the percentage of MDSCs in spleens from tumor–bearing WT mice. However, further analysis determined that the deficiency of TIMP-2 affects the expression of the BM-precursor marker VEGF-R1 by MDSCs in the spleens from tumor-bearing timp2−/− cell. This increased expression of cell surface VEGF-R1 was also demonstrated by VEGF-R1+ MDSCs in timp2−/− tumors.

The increased number of VEGF-R1+ MDSCs in timp2−/− tumors may suggest additional changes in the tumor microenvironment, and clearly defines the role of activated MMPs in the MDSC function. TIMP-2 deficient tumors triggered the activation of matrix metalloproteinases that can mediate MDSC infiltration into tumors as well as, the release of inflammatory factors such as some members of the TNF-family including CD40L and cognate receptor52. This could explain the rise in CD40L in timp2−/− tumors. CD40L is pivotal for the differentiation and antigen presenting functions of dendritic cells. However, little information has been reported on the role of CD40L in MDSC function39. Further research is needed to fully determine the role of CD40L in immature myeloid cells and in their interaction with T-cells.

The effects of TIMP-2 on the recruitment and pro-tumor functions of VEGF-R1+ MDSCs were validated in the human NSCLC model A-549. Forced TIMP-2 expression in A549 xenografts disrupts the recruitment of MDSCs and concomitantly decreases angiogenesis and tumor growth. Increased TIMP-2 expression in A549 cells also modulated inflammation by blocking the release of IL-6 in vitro (manuscript submitted for publication). Therefore, these findings demonstrate that TIMP-2 targets immature myeloid inflammatory cells along with their associated function in tumor angiogenesis and inflammation47.

Myeloid-derived-suppressor cells are now seen as targets of anti-cancer therapy, either for their tumor immune immunosuppressing functions and/or for their proangiogenic properties15. They are believed to be the cause of the poor response to tumor immunotherapies29,30 and resistance to anti-angiogenic treatments30. We have previously reported TIMP-2 effects on VEGF-A dependent pathways in vitro35 and in the present study we demonstrate the effects in vivo of TIMP-2 on the MDSC-associated immunosuppression and angiogenesis in lung cancer with important clinical implications53. The findings in this study support TIMP-2 as a negative regulator of MDSCs; therefore, making TIMP-2 a potential adjuvant in the immune therapy of NSCLC.

Methods

Cells

Lewis lung carcinoma (LL-2) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in high glucose Dulbecco's Modified Medium (DMEM), A-549 cells transfected with both a retroviral empty-vector (EV) A549Controls or a vector carrying timp-2, A549TIMP-2 were previously reported47 and cultured in RPMI. Media were supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine.

Mice

C57BL/6 timp-2−/− deficient mice were previously described54, maintained in heterozygous conditions. Wild-type (WT) and timp-2−/− littermates (6 –8 week old) were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 Lewis lung carcinoma cells. Tumor volumes were determined by Caliper measurements.

Female athymic (nu/nu) nude mice were injected subcutaneously with 5 × 106 A549Control or A549TIMP-2 cells. Mouse experiments were performed with the approval of the National Institutes of Health Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vivo molecular imaging

Mice were injected according to manufacturer's instructions with the following infrared imaging agents: Angiosense and Integrinsense (Visen Medical, Bedford MA). Infrared in vivo optical imaging was registered in a Pearl imager and analyzed using Pearl Impulse software (LI-COR, NE). In vivo concentration of imaging agents was determined by fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) in a FMT2500 scanner (Visen Medical).

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor samples were either fixed in 10% formalin or frozen in Optimum Cutting Temperature (OCT) medium. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5 μm paraffin-embedded tumor sections using the avidin-peroxidase method with a Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). Slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with mAb-CD45 (Biolegend, San Diego CA), followed by color development using 3,3' diaminobenzidine (DAB) reagent (Sigma). Slides were also stained for H&E. Frozen tumor sections were cut 10–12 μm in a cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Germany), fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min and stained at RT for 2 hour with the following antibodies: Alexa488-CD31, PE-CD11b, APC-F4/80 (Biolegend), APC-VEGF-R1 (R&D Systems, MN) and counterstained with mounting media containing DAPI (InVitrogen). For the intracellular staining of TIMP-2, frozen sections were fixed in cold acetone and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X in PBS. Sections were stained overnight with a rabbit-anti TIMP-2 antibody (MyBiosource) and FITC-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (InVitrogen). Sections were analyzed in an epi-fluorescence microscope (Olympus, PA) equipped with UPlanFL objectives, and AxionVision software (Zeiss, Germany) or in a LSM510 confocal microscope using Zen2009 software (Zeiss).

Flow Cytometry

Spleens from tumor-free and tumor bearing WT and timp-2−/− mice were isolated and passed through 70 μm filter, treated with ACK lysing buffer, rinsed in PBS and stained with mAbs for PE-CD11b, APC-F4/80, FITC-Gr-1 (Biolegend), APC-VEGF-R1 (R&D Systems) and isotype controls: APC-rat IgG2a, FITC-rat IgG, and PE-rat IgG (Biolegend). Cells were analyzed in a FACSCalibur using CellQuest Software (BD Biosciences).

Western Blots

Proteins from tumors and isolated splenocytes were extracted in RIPA buffer (Sigma, MO) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors, and applied to acrylamide gels. After SDS-Electrophoresis, gels were transferred to nitrocellulose filters and blotted with the following antibodies: Annexin A1 (Cell Signaling), p50 NF-κB, Tubulin-α, HRP-donkey anti rabbit (Biolegend), GAPDH and HRP-rabbit anti goat, -goat anti rabbit (Santa Cruz, CA) and signal developed using ECL Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare, UK).

RNA purification and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from WT and TIMP-2 deficient tumors using RNeasy Kit and Quiashredder column (QIAGEN). Three microgram of RNA was reversed transcribed using RT2 First Strand kit (QIAGEN) hybridized to a Mouse Cytokine and Chemokine PCR Array plates (SABiosciences). Quantitative PCR was performed on a 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Results were analyzed and data interpreted by using SABiosciences'web-based PCR array data analysis tool.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISA Kits (R&D Systems) were used to determine IL-6 and VEGF-A concentration in serum samples from WT and timp-2−/− mice, following manufacturer's instructions.

MMP activity

In vivo MMP activity was determined by injecting mice with a MMP-activated fluorogenic agent, MMPsense (Visen Medical) 24 hr prior to tumor dissection. MMP activation was detected as the Infrared fluorescence emission in tumor frozen sections.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between multiple groups were performed with 2-sided ANOVA test using Prism (Graphpad Software, Inc. CA). Comparisons between two groups was performed using Student's t- test, results were significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Effects of TIMP-2 in VEGF-A induced angiogenesis in vivo and secretion by LL-2 tumor cells in vitro. (A) Directed in vivo angiogenesis assay (DIVAA) was performed to measure angiogenesis response to VEGF-A in WT and timp-2−/− deficient mice. FITC-dextran accumulated in Angioreactors implanted in timp-2-deficient versus WT mice (n=5 in each group, means ± SEM **p<0.05). Low levels of angiogenesis in PBS containing Angioreactors from WT and timp-2 deficient mice as determined by FITC-dextran (n=5, means ± SEM., p=ns). (B) Zymography of condition media of LL-2 cells treated in vitro with rTIMP-2 showing decreased MMP-2 gelatinase activity. (C) Enzyme-linked Immunoassay of secreted VEGF-A by LL-2 cells treated with TIMP-2 (200 nM) vs. control untreated cells (n=6 in each condition, means ± SD, p<0.05).

TIMP-2 expression in spleens from tumor-bearing mice. (A) Spleen sections from tumor-bearing mice showing CD11b+ splenocytes and TIMP-2 expression in WT spleens, scale bar= 50 μm. (B) A higher magnification showing intracellular TIMP-2 by CD11b+ splenocytes (yellow fluorescence) and secreted TIMP-2 in the stroma (arrow) of spleens from tumor-bearing WT mice versus TIMP-2 negative myeloid cells in tumor bearing timp-2−/− mice, scale bar= 20 μm. (C) Splenomegaly in tumor bearing timp-2−/− mice versus WT spleens, scale bar= 0.5 cm. (D) Quantitation of spleen areas from tumor-bearing WT and timp2−/− mice ( n=8 in each group, mean ± SD).

Effects of TIMP-2 upregulation in A-549 tumor growth and angiogenesis (A) Reduced angiogenesis as determined by VEGF-R2 ultrasound in A549TIMP-2 xenotransplants versus A549Control xenografts at day 7 (n=5 in each group, means ± SD, p =n.s.) and day 14 post-transplant (**p=0.003). (B) Tumor growth of A-549 cells with upregulated TIMP-2, A549TIMP-2 versus A549Control tumors (means± SEM, **p=0.021).

Acknowledgments

Authors thank to Mr. Nimit Patel, Ms. Lisa Riffle and Dr. Joseph Kalen (NCI- Small Animal Imaging Program) for performing the VEGF-R2 microbubble ultrasound experiments, and Mr. Gilberto Prudencio (Visen Medical) for his assistance with fluorescence molecular tomography. This work was supported by funds from the Center for Cancer Research, NCI intramural project numberZ01 SC009179-20.

This work was supported by funds from the Center for Cancer Research, NCI Intramural Program

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: All authors have declared there are no financial conflicts of interest in regards to this work.

References

- 1.Saijo Y, Tanaka M, Miki M, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 beta promotes tumor growth of Lewis lung carcinoma by induction of angiogenic factors: in vivo analysis of tumor-stromal interaction. J Immunol. 2002 Jul 1;169(1):469–475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ottino P, Finley J, Rojo E, et al. Hypoxia activates matrix metalloproteinase expression and the VEGF system in monkey choroid-retinal endothelial cells: Involvement of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity. Mol Vis. 2004 May 17;10:341–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung YJ, Isaacs JS, Lee S, Trepel J, Neckers L. IL-1beta-mediated up-regulation of HIF-1alpha via an NFkappaB/COX-2 pathway identifies HIF-1 as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J. 2003 Nov;17(14):2115–2117. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0329fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafii S, Avecilla S, Shmelkov S, et al. Angiogenic factors reconstitute hematopoiesis by recruiting stem cells from bone marrow microenvironment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003 May;996:49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hattori K, Heissig B, Wu Y, et al. Placental growth factor reconstitutes hematopoiesis by recruiting VEGFR1(+) stem cells from bone-marrow microenvironment. Nat Med. 2002 Aug;8(8):841–849. doi: 10.1038/nm740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vroling L, Yuana Y, Schuurhuis GJ, et al. VEGFR2 expressing circulating (progenitor) cell populations in volunteers and cancer patients. Thromb Haemost. 2007 Aug;98(2):440–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alison MR, Lim S, Houghton JM. Bone marrow-derived cells and epithelial tumours: more than just an inflammatory relationship. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009 Jan;21(1):77–82. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32831de4cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao D, Mittal V. The role of bone-marrow-derived cells in tumor growth, metastasis initiation and progression. Trends Mol Med. 2009 Aug;15(8):333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torroella-Kouri M, Silvera R, Rodriguez D, et al. Identification of a subpopulation of macrophages in mammary tumor-bearing mice that are neither M1 nor M2 and are less differentiated. Cancer Res. 2009 Jun 1;69(11):4800–4809. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corzo CA, Condamine T, Lu L, et al. HIF-1alpha regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Med. Oct 25;207(11):2439–2453. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eruslanov E, Daurkin I, Ortiz J, Vieweg J, Kusmartsev S. Pivotal Advance: Tumor-mediated induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and M2-polarized macrophages by altering intracellular PGE catabolism in myeloid cells. J Leukoc Biol. Nov;88(5):839–848. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1209821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells in human diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. Jan 13; doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006 Feb;16(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solito S, Falisi E, Diaz-Montero CM, et al. A human promyelocytic-like population is responsible for the immune suppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood. 2011 Aug 25;118(8):2254–2265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008 Aug;8(8):618–631. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye XZ, Yu SC, Bian XW. Contribution of myeloid-derived suppressor cells to tumor-induced immune suppression, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis. J Genet Genomics. Jul;37(7):423–430. doi: 10.1016/S1673-8527(09)60061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seandel M, Butler J, Lyden D, Rafii S. A catalytic role for proangiogenic marrow-derived cells in tumor neovascularization. Cancer Cell. 2008 Mar;13(3):181–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis C, Murdoch C. Macrophage responses to hypoxia: implications for tumor progression and anti-cancer therapies. Am J Pathol. 2005 Sep;167(3):627–635. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duda DG, Jain RK. Premetastatic lung “niche”: is vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 activation required? Cancer Res. Jul 15;70(14):5670–5673. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan HH, Pickup M, Pang Y, et al. Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells tip the balance of immune protection to tumor promotion in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Res. Aug 1;70(15):6139–6149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawson MR, Duda DG, Chae SS, Fukumura D, Jain RK. VEGFR1 activity modulates myeloid cell infiltration in growing lung metastases but is not required for spontaneous metastasis formation. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e6525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, et al. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009 Jan 6;15(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005 Dec 8;438(7069):820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004 Oct;6(4):409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez LO, Pidal I, Junquera S, et al. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in mononuclear inflammatory cells in breast cancer correlates with metastasis-relapse. Br J Cancer. 2007 Oct 8;97(7):957–963. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melani C, Sangaletti S, Barazzetta FM, Werb Z, Colombo MP. Amino-biphosphonate-mediated MMP-9 inhibition breaks the tumor-bone marrow axis responsible for myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and macrophage infiltration in tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 2007 Dec 1;67(23):11438–11446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawinkels LJ, Zuidwijk K, Verspaget HW, et al. VEGF release by MMP-9 mediated heparan sulphate cleavage induces colorectal cancer angiogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2008 Sep;44(13):1904–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabitass RF, Annels NE, Stocken DD, Pandha HA, Middleton GW. Elevated myeloid-derived suppressor cells in pancreatic, esophageal and gastric cancer are an independent prognostic factor and are associated with significant elevation of the Th2 cytokine interleukin-13. Cancer Immunol Immunother. Oct;60(10):1419–1430. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shojaei F, Wu X, Malik AK, et al. Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007 Aug;25(8):911–920. doi: 10.1038/nbt1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finke J, Ko J, Rini B, Rayman P, Ireland J, Cohen P. MDSC as a mechanism of tumor escape from sunitinib mediated anti-angiogenic therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011 Jul;11(7):856–861. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stetler-Stevenson WG, Seo DW. TIMP-2: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis. Trends Mol Med. 2005 Mar;11(3):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guedez L, Lim MS, Stetler-Stevenson WG. The role of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in hematological disorders. Crit Rev Oncog. 1996;7(3–4):205–225. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v7.i3-4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fassina G, Ferrari N, Brigati C, et al. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases: regulation and biological activities. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2000;18(2):111–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1006797522521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seo DW, Li H, Guedez L, et al. TIMP-2 mediated inhibition of angiogenesis: an MMP-independent mechanism. Cell. 2003 Jul 25;114(2):171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00551-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SJ, Tsang PS, Diaz TM, Wei BY, Stetler-Stevenson WG. TIMP-2 modulates VEGFR-2 phosphorylation and enhances phosphodiesterase activity in endothelial cells. Lab Invest. Mar;90(3):374–382. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karin M, Greten FR. NF-kappaB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005 Oct;5(10):749–759. doi: 10.1038/nri1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maxwell PJ, Gallagher R, Seaton A, et al. HIF-1 and NF-kappaB-mediated upregulation of CXCR1 and CXCR2 expression promotes cell survival in hypoxic prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007 Nov 15;26(52):7333–7345. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forst B, Hansen MT, Klingelhofer J, et al. Metastasis-inducing S100A4 and RANTES cooperate in promoting tumor progression in mice. PLoS One. 5(4):e10374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan PY, Ma G, Weber KJ, et al. Immune stimulatory receptor CD40 is required for T-cell suppression and T regulatory cell activation mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Cancer Res. Jan 1;70(1):99–108. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kusmartsev S, Eruslanov E, Kubler H, et al. Oxidative stress regulates expression of VEGFR1 in myeloid cells: link to tumor-induced immune suppression in renal cell carcinoma. J Immunol. 2008 Jul 1;181(1):346–353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyden D, Hattori K, Dias S, et al. Impaired recruitment of bone-marrow-derived endothelial and hematopoietic precursor cells blocks tumor angiogenesis and growth. Nat Med. 2001 Nov;7(11):1194–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perretti M, D'Acquisto F. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009 Jan;9(1):62–70. doi: 10.1038/nri2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams SL, Milne IR, Bagley CJ, et al. A proinflammatory role for proteolytically cleaved annexin A1 in neutrophil transendothelial migration. J Immunol. Sep 1;185(5):3057–3063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He ZY, Wen H, Shi CB, Wang J. Up-regulation of hnRNP A1, Ezrin, tubulin beta-2C and Annexin A1 in sentinel lymph nodes of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. Oct 7;16(37):4670–4676. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i37.4670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Graauw M, van Miltenburg MH, Schmidt MK, et al. Annexin A1 regulates TGF-beta signaling and promotes metastasis formation of basal-like breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 6 Apr;107(14):6340–6345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913360107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yi M, Schnitzer JE. Impaired tumor growth, metastasis, angiogenesis and wound healing in annexin A1-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Oct 20;106(42):17886–17891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901324106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourboulia D, Jensen-Taubman S, Rittler MR, et al. Endogenous Angiogenesis Inhibitor Blocks Tumor Growth via Direct and Indirect Effects on Tumor Microenvironment. Am J Pathol. Sep 17; doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. Mar 4;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamano Y, Zeisberg M, Sugimoto H, et al. Physiological levels of tumstatin, a fragment of collagen IV alpha3 chain, are generated by MMP-9 proteolysis and suppress angiogenesis via alphaV beta3 integrin. Cancer Cell. 2003 Jun;3(6):589–601. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00133-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Younos I, Donkor M, Hoke T, et al. Tumor- and organ-dependent infiltration by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Int Immunopharmacol. Jul;11(7):816–826. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burton VJ, Butler LM, McGettrick HM, et al. Delay of migrating leukocytes by the basement membrane deposited by endothelial cells in long-term culture. Exp Cell Res. 2011 Feb 1;317(3):276–292. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004 Aug;4(8):617–629. doi: 10.1038/nri1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG, di Tomaso E, et al. AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients. Cancer Cell. 2007 Jan;11(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caterina JJ, Yamada S, Caterina NC, et al. Inactivating mutation of the mouse tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2(Timp-2) gene alters proMMP-2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2000 Aug 25;275(34):26416–26422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of TIMP-2 in VEGF-A induced angiogenesis in vivo and secretion by LL-2 tumor cells in vitro. (A) Directed in vivo angiogenesis assay (DIVAA) was performed to measure angiogenesis response to VEGF-A in WT and timp-2−/− deficient mice. FITC-dextran accumulated in Angioreactors implanted in timp-2-deficient versus WT mice (n=5 in each group, means ± SEM **p<0.05). Low levels of angiogenesis in PBS containing Angioreactors from WT and timp-2 deficient mice as determined by FITC-dextran (n=5, means ± SEM., p=ns). (B) Zymography of condition media of LL-2 cells treated in vitro with rTIMP-2 showing decreased MMP-2 gelatinase activity. (C) Enzyme-linked Immunoassay of secreted VEGF-A by LL-2 cells treated with TIMP-2 (200 nM) vs. control untreated cells (n=6 in each condition, means ± SD, p<0.05).

TIMP-2 expression in spleens from tumor-bearing mice. (A) Spleen sections from tumor-bearing mice showing CD11b+ splenocytes and TIMP-2 expression in WT spleens, scale bar= 50 μm. (B) A higher magnification showing intracellular TIMP-2 by CD11b+ splenocytes (yellow fluorescence) and secreted TIMP-2 in the stroma (arrow) of spleens from tumor-bearing WT mice versus TIMP-2 negative myeloid cells in tumor bearing timp-2−/− mice, scale bar= 20 μm. (C) Splenomegaly in tumor bearing timp-2−/− mice versus WT spleens, scale bar= 0.5 cm. (D) Quantitation of spleen areas from tumor-bearing WT and timp2−/− mice ( n=8 in each group, mean ± SD).

Effects of TIMP-2 upregulation in A-549 tumor growth and angiogenesis (A) Reduced angiogenesis as determined by VEGF-R2 ultrasound in A549TIMP-2 xenotransplants versus A549Control xenografts at day 7 (n=5 in each group, means ± SD, p =n.s.) and day 14 post-transplant (**p=0.003). (B) Tumor growth of A-549 cells with upregulated TIMP-2, A549TIMP-2 versus A549Control tumors (means± SEM, **p=0.021).