Abstract

Following the death of a loved one, a small group of grievers develop an abnormal grieving style, termed complicated or prolonged grief. In the effort to establish complicated grief as a disorder in DSM and ICD, several attempts have been made over the past two decades to establish symptom criteria for this form of grieving. Complicated grief is different from depression and PTSD yet often comorbid with other psychological disorders. Meta-analyses of grief interventions show small to medium effect sizes, with only few studies yielding large effect sizes. In this article, an integrative cognitive behavioral treatment manual for complicated grief disorder (CG-CBT) of 25 individual sessions is described. Three treatment phases, each entailing several treatment strategies, allow patients to stabilize, explore, and confront the most painful aspects of the loss, and finally to integrate and transform their grief. Core aspects are cognitive restructuring and confrontation. Special attention is given to practical exercises. This article includes the case report of a woman whose daughter committed suicide.

Keywords: Prolonged grief, complicated grief, treatment, cognitive behavior therapy, bereavement, death and dying

Acute grief in the aftermath of the death of a loved one is a normal yet painful process. Defining normal grief is difficult, as there are lots of variations in the experience and expression of acute grief, mitigated by culture, gender, personality, and circumstances of life. Mostly, the dominant emotion after the loss of a loved one is sadness sometimes combined with other emotions such as anger. The main function of normal grief and sadness after bereavement is resignation finally leading to adjust to the new situation. Another function of sadness is that it elicits empathy and support from others due to the facial expression of the griever (for a review see Bonanno, 2009). Grief in its various forms is not a psychological disorder in itself and warnings of unjustified pathologizing are to be taken seriously. Yet, 6 months postmortem, most people's grief symptoms have decreased substantially. Only a small group of grievers develop symptoms leading to profound functional and emotional impairment in daily life. For those, the pain of grieving is experienced more intensively. There are two symptom clusters of complicated grief: The first cluster is separation distress in the form of strong yearning for the deceased; the second cluster is constituted by a number of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral factors. Prevalences for these abnormal forms of grieving vary depending on applied criteria and sample characteristics between 2.4% in Japan (Fujisawa et al., 2010), 3.7% in Germany (Kersting, Brähler, Glaesmer, & Wagner, 2011), and 4.2% in Switzerland (Maercker et al., 2008). Shear et al. (2011) estimated that about 10% of all bereaved people develop abnormal grief.

In the effort to describe “abnormal” grief, a number of diagnostic concepts have been published over the years. Most prominent were the concepts of “complicated grief” and “traumatic grief.”

The term “complicated grief” was developed by Horowitz and colleagues (Horowitz et al., 1997, 2003; Prigerson et al., 1995), whereas “traumatic grief” was used by Prigerson and colleagues (Jacobs, 1999; Prigerson et al., 1997; Shear et al., 2001). The concepts evolved and criteria and definitions varied in the process (for an overview see Shear et al., 2011). This variation makesitdifficultfornon-professionalstodiffentiate between the competing concepts.

Neither DSM-IV nor ICD-10 includes a specific diagnosis for abnormal grief processes yet. However, in the course of developing a concept for the revision of DSM-IV, a group of experts in the field agreed on new criteria for a diagnosis “prolonged grief disorder” (Prigerson et al., 2009). The respective criteria are displayed in Table 1: Consensus Criteria of Prolonged Grief Disorder proposed for DSM-V (Prigerson et al., 2009). The ongoing discussion can be followed at http://www.dsm5.org/PROPOSEDREVISIONS/Pages/ConditionsProposedbyOutsideSources.aspx (retrieved September 5, 2011).

Table 1.

Consensus criteria of prolonged grief disorder proposed for DSM-V (Prigerson et al., 2009)

| A. | Event criterion: Bereavement (loss of a loved person). |

| B. | Separation distress: The bereaved person experiences at least one of the three following symptoms that must be experienced daily or to a distressing or disruptive degree: |

| 1. Intrusive thoughts related to the lost relationship. | |

| 2. Intense feelings of emotional pain, sorrow, or pangs of grief related to the lost relationship. | |

| 3. Yearning for the lost person. | |

| C. | Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms: |

| The bereaved person must have five (or more) of the following symptoms: | |

| 1. Confusion about one's role in life or diminished sense of self (i.e., feeling that a part of oneself has died). | |

| 2. Difficulty accepting the loss. | |

| 3. Avoidance of reminders of the reality of the loss. | |

| 4. Inability to trust others since the loss. | |

| 5. Bitterness or anger related to the loss. | |

| 6. Difficulty moving on with life (e.g., making new friends, pursuing interests). | |

| 7. Numbness (absence of emotion) since the loss. | |

| 8. Feeling that life is unfulfilling, empty, and meaningless since the loss. | |

| 9. Feeling stunned, dazed, or shocked by the loss. | |

| D. | Duration: Diagnosis should not be made until at least six months have elapsed since the death. |

| E. | Impairment: The above symptomatic disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (e.g., domestic responsibilities). |

| F. | Medical exclusion: The disturbance is not due to the physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition. |

| G. | Relation to other mental disorders: Not better accounted for by Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. |

In our randomized controlled clinical trial, we used the criteria defined for prolonged grief disorder. Yet, to comply with most of the published literature, the term complicated grief disorder (CGD) shall be used in this article. The patient's case report following in the later part of this text is taken from this trial.

A number of studies published in the last years showed that prolonged grief can be differentiated from depression and PTSD (Boelen & Van den Bout, 2005; Boelen, Van den Hout, & Van den Bout, 2008). Differences between CGD and PTSD can be summarized as follows: (1) While yearning symptoms are the hallmark symptom group for CGD, intrusive symptoms are the core symptom group for PTSD. (2) While intrusions in PTSD are often accompanied by anxiety and related to the traumatic event, CGD intrusions are bittersweet (negative and positive simultaneously). (3) While for PTSD, the second additional symptom group are hyperarousal symptoms, the second additional symptom group for CGD are failure-to-adapt symptoms. (4) Minimum duration of PTSD is 1 month and for CGD 6 months (for an overview and discussion see Maercker & Znoj, 2010).

Differences between CGD and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) are: (1) CGD has the loss of a loved one as cause, whereas bereavement is an exclusion criterion for MDD; Thus, CGD is based on an event criterion. (2) While yearning symptoms are the core symptom group for CGD, depressed mood or loss of interest are the core symptoms for MDD. (3) Minimum duration varies between the two disorders. Furthermore, there are number of physiological differences: CGD and MDD differ in EEG during sleep and react differently to tricyclic antidepressants (for an overview see Rosner & Wagner, 2009). However, despite conceptual differences between complicated grief, depression, and PTSD, CGD is often comorbid with other disorders (Maercker & Znoj, 2010; Rosner & Wagner, 2009). In summary, as long as CGD is not accepted as an official diagnosis, clinicians have to diagnose different inadequate disorders that may then be followed by inadequate treatment. This is supported by the results reported by Shear et al. (2011). They enrolled 243 individuals seeking treatment for CGD in a study. Many had been on treatment seeking odysseys for years. Eighty five percent of those patients had tried at least one medication or one form of counseling.

1. Empirically evaluated treatments for complicated grief

Between 1999 and 2000, three meta-analyses on outcome research with grieving individuals were published (Allumbaugh & Hoyt, 1999; Fortner, 2000; Kato & Mann, 1999). In total, effect sizes for studies with randomized controlled design were small d=0.11 (Kato & Mann, 1999); d=0.13 (Fortner, 2000) to medium d=0.43 (Allumbaugh & Hoyt, 1999). While Kato and Mann (1999) and Fortner (2000) reported only on controlled studies, Allumbaugh and Hoyt (1999) included uncontrolled studies as well that resulted in a medium effect size. However, as intensity and symptoms of grief generally improve substantially during the first months of bereavement, controlled designs are imperative.

In 2005, we decided to conduct a meta-analysis as the number of studies had substantially increased since 1999. We wanted to find out if treatment efficacy had improved. This meta-analysis was based on more than 50 studies with a randomized controlled design and yielded an overall effect size (ES) of 0.20 (Rosner & Hagl, 2007; Rosner, Kruse, & Hagl, 2005). Dividing the studies into preventive studies (only bereavement as intake criterion) and psychotherapy studies (bereavement and increased grief scores) yielded ES of 0.04 for preventive studies as compared to 0.27 for psychotherapy studies. In this meta-analysis, all successful studies (defined as having ES>0.80) included specific interventions to build rapport and enhance treatment motivation, to confront painful aspects, and to allow reconciliation and integration of the new and changed relationship for the bereaved.

One highly effective treatment was for example Shear et al.'s complicated grief treatment (CGT; Shear, Frank, Houck, & Reynolds, 2005). In this study, Shear et al. (2005) compared two active treatments, interpersonal therapy and CGT. One of them, CGT achieved a pre to post ES of 1.63. CGT is a combination of CBT and interpersonal therapy. Another highly effective intervention is the internet-based therapy for complicated grief by Wagner, Knaevelsrud, and Maerker (2006) with a pre–post ES of 1.41. The internet-based therapy applied a three phase model consisting of confrontation, cognitive restructuring, and social sharing. Other promising interventions were described in a publication by Melges and De Maso (1980) concerning grief resolution and in Rando's (1993) description of Gestalt and psychodrama interventions.

In terms of confrontation and cognitive interventions, aspects from two PTSD interventions seemed adaptable to CGD in adults: Ehlers’ manual on the treatment of PTSD in adults (Ehlers, 1999) and Cohen, Mannarino, and Deblinger's manual (2006) on the treatment of PTSD and grief in children. Both manuals were tested in several studies and showed very large effect sizes.

Based on this information, we developed a treatment manual consisting of the most promising elements for successful therapy. This treatment manual's structure was later adapted for in-patient treatment and showed large ES of 1.21 for in-patients with comorbid complicated grief (Rosner, Lumbeck, & Geissner, 2011). Our randomized controlled study on outpatient treatment of patients suffering from comorbid complicated grief started in 2005, and the case report is based on one of the patients in this study (Rosner, Pfoh, & Kotoucova, in preparation).

Since 2005, two more meta-analyses have been published, whose results confirm the older meta- analyses: Currier, Neimeyer, and Berman (2008) reported an overall ES of 0.16 and a medium ES of 0.51 for studies based on subjects with increased grief symptom severity at the beginning of treatment. The newest meta-analysis compared preventive interventions and treatment interventions for CGD and found an ES of 0.03 for prevention and 0.53 for treatment (Wittouck, Van Autreve, De Jaegere, Portzky, & Van Heeringen, 2011).

In terms of individual treatment studies for CGD, Boelen, de Keijser, Van den Hout, and Van den Bout (2007) compared two versions of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) vs. supportive counseling and reported pre to post effect sizes of 1.36 for the combination of cognitive restructuring followed by exposure and 1.80 for the combination of exposure followed by cognitive restructuring. Exposure in this study was prolonged exposure and followed the protocol of Foa and Rothbaum (1998).

In a nutshell, the summary of the literature review above is:

Preventive treatments for those who are bereaved, but do not show signs of CGD or other disorders are not effective.

There is a limited number of studies on CGD that show large ESs. Treatments evaluated in those studies incorporate some kind of exposure and cognitive restructuring. The three most successful treatments vary substantially in terms of treatment strategies applied.

The following paragraphs describe the outpatient treatment.

2. Description of the integrative cognitive behavioral treatment manual for complicated grief (CG-CBT)

The treatment manual is designed for 20–25 sessions. In accordance with the German health insurance standards, this is a typical amount of treatment sessions for CBT (http://www.ptk-hessen.de/web/Deutsch/Homepage/Psychotherapie/Psychotherapie_als_Versicherungsleistung/ retrieved September 5, 2011).

Treatment was proceeded by three to five diagnostic sessions utilizing the Interview for Prolonged Grief Disorder (PG––13; Prigerson et al., 2009) to determine CGD, the computer version of a standardized diagnostic system for DSM-IV diagnoses (Diagnostisches Expertensystem für Psychische Störungen, DIA-X; Wittchen & Pfister, 1997) to diagnose comorbid Axis I disorders, and the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 1977) to determine the severity of general distress symptoms by using the Global Severity Index (GSI).

Of those 25 treatment sessions, five are optional and directed toward special situations or occasions such as anniversaries, holidays, birthdays, family sessions, or legal proceedings/court days. Not all patients are in need of those. The remaining 20 sessions are divided into three parts, each with several treatment strategies, and form the standard treatment for all patients. Although it is a cognitive behavioral treatment manual, it borrows techniques from other therapeutic models such as relaxation techniques, Gestalt Therapy, Solution Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT), Multigenerational Family Therapy, and imagery work. With the exception of session 1, all sessions start with the question, “What has changed?” With that, the tone is set for an expectation of change. At the same time, this repetitive question provides a structure to the sessions. Table 2 provides an overview of session content and treatment strategies.

Table 2.

Session contents and treatment strategies

| Session number | Session content | Treatment strategies |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Admin. contracting, psychoeducation about treatment | Work sheet on social roles and tasks and symptoms, safety planning |

| A2 | Nodal events: My loss in a bigger perspective, stabilization | Genogram, life line, grounding exercises if necessary |

| A3 | Psychoeducation on normal and complicated grief and introduction of CG-model | Worksheets to prepare psychoeducation and CG model to enable the patient to recognize dysfunctional behavior and personal triggers |

| A4 | –– | – |

| A5 | Primary and secondary losses in my life | Introduction of the deceased with pictures, music, etc; worksheet on life changes due to bereavement |

| A6 | Review of information and treatment goals | Four blocker method similar to motivational interviewing: Advantages and disadvantages of change, worksheet on treatment motivation, and treatment goals |

| A7 | –– | –– |

| B8 oder | Relaxation | Introduction to relaxation, progressive muscle relaxation |

| B8 | Relaxation and demarcation | Imagery work addressing distressing cognitive stimuli followed by relaxation techniques |

| B9 | Identification of dysfunctional thoughts | Cognitive restructuring, metaphors, psychoeducation regarding thought processes, helpful, and non-helpful thoughts |

| B10 | Rumination and guilt | Socratic dialoge, reframing, metaphors, worksheet |

| B11 | Emotions and perceptions | Worksheet, dialoguing (Gestalt) |

| B12 & 13 | Worst moments: confrontation in sensu | Confrontation of thoughts, emotion, and/ or situations that are avoided |

| B14 | Worst moments and identification of “hot spots” | Identification of “hot spots” and dysfunctional cognitions, cognitive restructuring, reinterpretation; |

| Preparation of “Walk to the Grave” | ||

| B15 & 16 | Confrontation, cognitive restructuring, and acceptance | Dialogical work “Walk to the Grave” |

| C17 | Heritage and continuing bonds | Presentation/letter/essay, worksheet, home activities |

| C18 | Memento and future | Dialoguing or letter, description of new life, dedication |

| C19 | New life | Describing new status quo and life plan |

| C20 | Termination | Review, relapse prevention, feedback, questions |

| Optional | Family session––preparation | Identification of topics and tasks (for example, different ways of grieving in the family) |

| Optional | Family session––implementation | Dealing with different grieving styles; collateral narratives, circular questioning |

| Optional | Special event planning: | |

| Birthday, anniversary, holidays | Preparing plan, modify rituals, include social network | |

| Court appointments | Identify course of events, elicit information from lawyer, | |

| contact social support, carry out plan in sensu |

2.1. Therapeutic alliance, stabilization, exploration, and motivation

This part of treatment considers safety aspects for the patients and helps them to restructure their lives in a way they can start coping again with their daily routine. First, to establish safety, patients are asked to complete a worksheet with at least three names and phone numbers of friends or relatives to call in case they face a difficult time. Likewise, there is a worksheet for activities that help patients to master a difficult day, such as sports activities. These activities are based either on patients’ previous experiences or they are developed using the conversational method of SFBT. Another module considers the fact that the death of a loved one often alters the daily routine: It may be that the number of household members changed and the tasks of the deceased family member have to be transferred. It may also mean that the surviving family members have to redefine their roles. In any case, it means for the survivors that having fallen out of their original routine requires picking up new tasks and establishing a new routine. Perhaps the surviving husband has to organize his own meals or the mother of a deceased child needs to find an activity during that time she used to spend with her child doing homework. (Note that these steps should not be mistaken as a method of avoidance.) This module starts out using psychoeducation regarding social roles and tasks and their changes after someone has died. For example, by the means of a worksheet showing two people, patients start to describe the deceased person and their relationship to them. Then, they describe their complementary roles and respective tasks differentiating between practical and emotional tasks. Finally, the date of death is inserted into the picture between the two people as a dividing line marking the fact that most tasks have no complement anymore. This visualization aims to help patients to gain a greater acceptance of the death and aims to lead them to the understanding that the relationship has not ceased, but the quality thereof has changed. However, at this early point in treatment, this does not have to be articulated. For each task that is left by the deceased person, the patient asks the questions, (1) Do I take over this task, (2) Do I delegate this task to someone else, or (3) Will this task discontinue (or: not be taken care of)? Most often, this early time of treatment is about practical and hands-on interventions, for example “Who is now in charge of meals?” Of course, this can be revisited and redefined during a later part of treatment.

For patients who are experiencing affect instability and mild dissociation, the manual provides a brief and easy exercise in grounding. Patients are taught to refocus to the here and now by concentrating on themselves rubbing their fingers lightly over their knees or coat pockets (making contact with themselves), putting their feet firmly on the ground, and repeating their names, current location, date, and time thrice. This serves to replace negative thoughts with more neutral ones, to stop rumination, and to experience the reality of present time and location.

Finally, this part of treatment also expands and deepens clinical information gained through standardized tests prior to treatment, during the initial contact phase of diagnostics. Presenting a portfolio of the deceased person (including songs or mementos) or viewing a photo album together with the therapist allows the patients to reflect on their loved ones with all their characteristics. Likewise, with the help of a genogram, patients not only look at all the losses their family has endured but also learn about how their family dealt with grief. In this process, the therapist's validation of the magnitude of the loss helps to strengthen the therapeutic alliance.

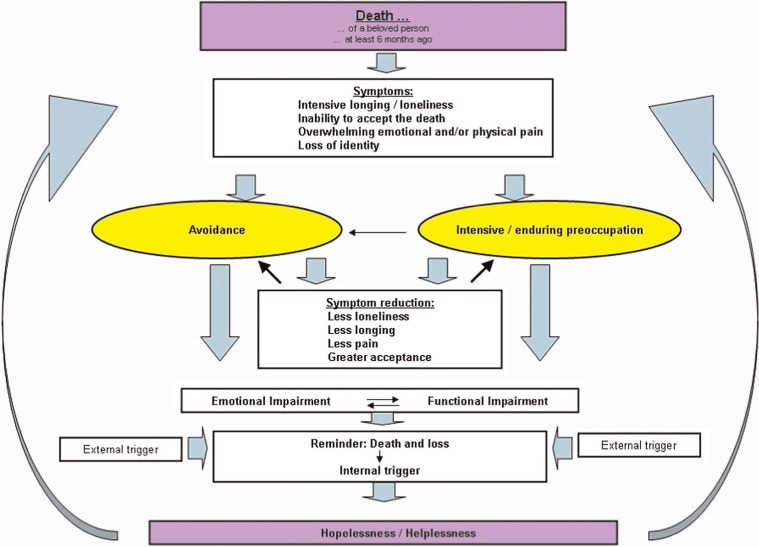

Psychoeducation and the use of the disease model of complicated grief (Fig. 1) aim toward helping patients to accept their behavior in their situation of grief (normalization). Psychoeducation also enables patients to actively reflect on the advantages and disadvantages of treatment and helps them to define their treatment goals. The opportunity for the therapist to establish herself as a competent partner via psychoeducation regarding grief treatment contributes to the therapeutic alliance. A sound and trustful professional relationship is essential to endure the intense emotional work of the next part of treatment.

Fig. 1.

Disease model of complicated grief disorder.

First, the model is used for explanation and, in a second step is enriched by details from the patient's personal story. Complicated grief presumes the death of a significant person at least 6 months ago. This bereavement leads to strong yearning and longing for the deceased, to problems with acceptance of death, to overwhelming emotional and/or physical pain, as well as to loss of identity. The bereaved respond to those symptoms with either avoidance or extensive preoccupation with the deceased. In the short run, this leads to symptom reduction. However, in the long run, it leads to emotional, cognitive, and/or functional impairment that, in turn, serve as a reminder of their loss and results in hopelessness and helplessness. The result is an intensification of symptoms.

2.2. Exposure and cognitive restructuring

This part is the core of our treatment manual. During confrontation, patients are exposed to the most difficult internal pictures or cognitions (hot spots) surrounding the death of their loved ones and, in particular, to their dysfunctional thoughts (or as they are termed with the patients “unhelpful thoughts”), and secondary emotions based on these thoughts. Before that, the manual foresees that patients become aware of the fact that much of their emotional reaction surrounding death and suffering of their loved ones is the product of their way of thinking (dysfunctional thought, interpretation). Special care is taken by the therapist not to reduce the suffering of anyone to the level of a mere dysfunctional thought, as otherwise the patients might feel invalidated. However, in reality, most often there is no account in regards to details of what happened just before death. These pictures are the product of patients’ imagination or their interpretation of the real event. Therefore, as a first step, those pictures are treated like a dysfunctional thought or an irrational belief. As a result, the picture that is left is the situation as it is documented and supported by facts. This picture then is confronted. Certainly, this part of treatment also includes dealing with issues such as blame, shame, guilt, and regret when finally patients participate in an exercise in which they dialog with their loved ones to reconcile their picture.

2.2.1. Three steps to transform dysfunctional thoughts

2.2.1.1. Cognitive restructuring: identification and confrontation of dysfunctional thoughts. Psychoeducation around the interplay of cognitions, emotions, and behavior starts this module. In an example story, the interrelationship between cognitions, emotions, and behavior is explained to the patients and helps them to remember these facts.

Next is the goal to eliminate imagined details (interpretation, dysfunctional thoughts) from the actual event. This is treated like the equivalent of differentiating the event from its interpretation, the dysfunctional thought. First, patients who are ruminating over the thought of how their loved one suffered before death are asked to precisely describe their idea of the picture. Next, they are asked to identify how they came to this knowledge because even when they witness the actual death, there is still room for their personal interpretations. Thus, the question, “how do you know, it happened this way?” helps patients to acknowledge that most details happen in their imagination. In a next step, patients are asked to eliminate those details (interpretations, dysfunctional thoughts) from their most terrible imagination. They themselves can come up with a way of doing this and often become very involved in creating options. In the end, there is only the fact-based picture (event) left. If details are reintroduced into the picture in a later session, patients utilize the technique they learnt earlier. They ask themselves three questions: (1) Is it realistic? (2) Is it unrealistic? or (3) Is it realistic, but not helpful for me to think this way and do I have alternatives?

While patients whose loved ones died of natural causes tend to ruminate over the question, “What could I have done differently that would have prevented the death and suffering?” virtually all patients whose loved ones died of non-natural causes ruminate over the question, “How severely has my loved one suffered before he or she died?” The latter thought they share with those, whose loved ones were missing and possibly tortured.

2.2.1.2. Experiencing the situation: exposure. Nevertheless, even after eliminating the imagined details, patients hold a certain picture in their mind that they are then asked to describe. This picture is the one without their interpretation or imagined details. Depending on the grade of literacy, this account is written down either by the patient or by the therapist. Next, patients add in their emotions and sensations. In the end, they experience this picture first in the role of a bystander, and later they actualize it in the here and now while they integrate emotions, sensations, and cognitions to the event.

2.2.1.3. Reconciliation: receiving forgiveness. The central exercise of this part is the “Walk to the Grave.” Following Gestalt therapy, patients dialog with their dead loved ones (For a more detailed description of chair work, see for example Daldrup, Beutler, Engle, & Greenberg, 1988). The therapist takes on the role of the director as well as the role of the double. Patients can differentiate between those roles by the position of the therapist in relation to the patient. Although this part gives patients the option of a free dialog, they are also asked to follow three leads: (1) What I always still wanted to tell you. (2) What I always still wanted to ask you. (3) This is how your death has impacted my life. Before the dialog, patients prepare the treatment room, setting up the stage as if it was the grave of their loved one. After their dialog, they switch roles and respond. It is during this step they make their final corrections and reinterpret their former dysfunctional thoughts That allows for reconciliation while they receive forgiveness from themselves and their loved ones.

2.3. Integration and transformation

This part of the manual pertains to the present and future of the patients. It deals with their hopes, intentions, and plans for the new life of the patients. Questions such as “How has my life changed since the death?” and “How will my life look in 3, 6, 9, and 12 months?” are central to the work with patients. In addition, patients decide on what memento/ritual they will dedicate to their loved ones? Part 3 also pays special attention to discharge and possible problems surrounding this issue.

3. Discussion of the proposed treatment approach in comparison with other treatments

The proposed treatment approach shares its overall structure with other CGD interventions: Psychoeducation and building up of a motivation for change, exposure and cognitive restructuring, integration, and transformation. On the level of individual interventions, the range of possible methods in our manual is larger and integrates methods from other models. We developed our manual to meet several goals:

Our main goal is to develop an effective treatment for CGD with low dropout rates for severely disordered patients. Therefore, we decided to include only comorbid patients into the study (each patient suffers from at least CGD and one other Axis 1 disorder). In none of the three treatment studies mentioned above (Boelen et al., 2007; Shear et al., 2005; Wagner et al., 2006), comorbidity is a required intake criterion and therefore comorbidity rates are not as large as in our study.

We chose to include only comorbid patients because we did recognize that this group is not represented in research. Furthermore, there seems to be a tendency––at least in Germany––that bereaved persons do not seek therapy; they rather join self-help groups, or they seek support offered by churches. Therefore, we included only patients who need therapeutic support.

As the dissemination of an effective treatment is one main goal, we tried to make our intervention attractive to therapists. Having more treatment options to serve one possible goal and adjusting length of treatment to German insurance standards is attractive as it allows a one-to-one session transfer into clinical practice.

The manual in itself follows a cognitive behavioral frame and explanation scheme but includes interventions worked out in detail in other psychotherapeutic schools. For example, to validate the loss and to facilitate the therapeutic alliance, we do not only look at pictures or listen to music but we also include genograms. Genograms were included after the pilot phase of the study, as we learnt that some patients need a representation of the way their family passes on their tradition of grieving to the next generation. The knowledge about family transmission serves to not only build up trust in the treatment, but also enriches psychoeducation.

Confrontation is a central part of most successful interventions: Yet, when looking at the way confrontation can be done, studies reported different methods: Shear et al. (2005) used a confrontational method they called “revisiting” that is similar to Foa and Rothbaum's prolonged exposure (1998), Wagner et al. (2006) used a writing task in their internet-based intervention and Boelen et al. (2007) used again prolonged exposure. We developed and applied a gentle method of confrontation to avoid patients dropout of treatment; we used confrontation in sensu, accompanied by working on cognitions. But therapist and patient may also choose to write about the most painful moments.

As many patients report that they constantly talk to their deceased loved ones anyway, we designed the intervention “walk to the grave.” This intervention follows the structure of a therapeutic experiment in Gestalt therapy. Despite its Gestalt origin, this intervention can be viewed as an exposure to a painful aspect of the loss. It also can be interpreted as a cognitive intervention becuase the leading questions are designed to come up with new thoughts and ideas about the loss.

Integrative interventions or a research informed selection of interventions are more common in the treatment of disorders such as substance abuse or depression (for an overview see Norcross & Goldfried, 2005) than for example in the treatment of PTSD. But even in the treatment of PTSD, two integrative approaches have been proven to be highly effective: Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy (BEP; Gersons, Carlier, Lamberts, & Van der Kolk, 2000; Lindauer et al., 2005.) and Cloitre's approach that combines “Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR)” and “Narrative Story Telling (NST)” (Cloitre, Cohen, & Koenen, 2006; Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, 2002). Both treatments use a strict CBT frame, and BEP has been classified in the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline (National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2005) as a trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Although BIP includes some elements of other therapeutic schools, its main treatment components overlap with those of other trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies. Contrary to BEP where different elements are more intertwined, Cloitre's manual works with two distinct steps, one is focusing on emotion regulation and another one on exposure. Keeping processes distinct allows a better estimation of what part of an intervention is the active ingredient and is therefore the method to apply, if one wants to test for components. The latter is one of the major shortcomings of our intervention as the different components cannot be tested for their respective contribution to outcome. Furthermore, some of the interventions, for example the “walk to the grave,” may seem difficult to learn, but almost all of the other interventions (such as genograms) are common therapeutic knowledge and tools.

4. Case report

Part 1: stabilization, exploration, and motivation

The 45-year-old married clerk, Mrs. T., contacted the university outpatient clinic after the elder of her two daughters had committed suicide. Three years ago, her daughter had taken a knife and cut her veins in the family's swimming pool. Mrs. T. found her. Before, mother and daughter had spent the day together. Mrs. T. had offered help to her unemployed daughter assisting her in her job search. However, Mrs. T. had become angry with her daughter for her lack of motivation. Later, Mrs. T. went shopping with a friend. When she returned from the shopping trip, she found her daughter dead. Since then, Mrs. T. has been longing for her daughter to the point she physically aches. She also suffered from anxiety, especially when alone. She avoided social contacts because she did not want to be asked about her daughter. She constantly thought about her daughter and how she might have suffered in the moment before death. Results from the diagnostic sessions with Mrs. T. showed that she not only suffered from CGD but also from MDD. The GSI was elevated (1.51).

During the months before her death, the daughter had withdrawn from people around her, including her mother. Mrs. T. had not understood the reasons for that and why her daughter did not want to talk to her. At the time when Mrs. T. started treatment, she assumed that she had done something wrong that contributed to her daughter's death. Mrs. T. ruminated about what she could have done to prevent her daughter's death and suffering.

When Mrs. T. worked on the model of complicated grief, she realized that she avoided everything that reminded her of her daughter to avoid the pain over her death. On the other hand, Mrs. T. suffered from intrusions: She kept seeing her daughter face down in the bloody pool water. By avoiding external triggers to avoid the pain over the death of her daughter, Mrs. T.'s symptoms of complicated grief were upheld. She realized that her ruminations served the same purpose.

Part 2: confrontation, exposure, and reinterpretation

Mrs. T. was telling the story of the day her daughter died including all the details of the picture she had in mind. Focus of phase 2 was to identify, eliminate, and confront her dysfunctional thoughts. Mrs. T. believed that her daughter's death was her fault because she was the one responsible for the welfare of the family. With that she had failed in her own opinion. She was suffering from intrusions concerning the death of her daughter and believed that her daughter suffered and felt abandoned and alone in her moment of death. She was convinced that her daughter was disappointed in her. These beliefs were checked on their content of reality and Mrs. T. realized that in fact she did not know what the situation or the thoughts of her daughter in the moment of her death really had been. She also realized that the carrousel of her dysfunctional thoughts was not helpful for her.

The worst moment (hot spot) to think of for Mrs. T. was when she found her daughter. During confrontation, Mrs. T. was first asked to eliminate those imagined details from the picture she had in mind. Then, she was asked to re-experience the situation in sensu, paying attention to her emotions and sensations.

In a last opportunity to communicate with her daughter, Mrs. T. participated in the exercise “Walk to the Grave.” Here, she had the opportunity to ask and tell her daughter everything she still wanted to ask and tell. She asked questions like, “Why did you do it? Did you suffer? Could I have done anything different so you would have decided to stay alive? What did I do wrong?” First, Mrs. T. described her daughter's grave. Then, she arranged different things of the therapy room to represent the grave. Finally, she stood in front of the grave to talk to her daughter before she lay down to take the position of the daughter responding to her mother. This was the turning point of therapy. To her daughter, Mrs. T. said that she did not want to live anymore and that she did not see a future for herself. Her daughter explained that she was afraid of being hospitalized for a mental disorder, that she was an adult now, and no longer did she have to share all her thoughts with her parents. She stated that she was responsible for her own actions. Finally, she stated that nobody could have prevented her death because she had made up her mind. With that, she apologized to her mother. Mrs. T. cried a lot during this session. She realized that she had not only lost her daughter to death but also a child to adulthood. However, in the next session, she reported that she felt less angry and that, for the first time, she was able to remember good times she had with her daughter, such as their frequent trips to Italy.

Part 3: integration and transformation

During this phase of treatment, Mrs. T. wrote a letter to her daughter in which she described how her life has changed after her death. In doing that, she also realized that all she focused on was her deceased daughter, whereas her other daughter and her grandchildren were widely neglected. Mrs. T. vowed to change this. She decided to participate more in the life of her loved ones and refreshed contacts with old friends. She also found a part time job that she enjoyed greatly. During her last session, Mrs. T. defined her plans for her future life. She described examples how she wants to be part in the lives of her loved ones.

For the abstract or full text in other languages, please see Supplementary files under Reading Tools online

Conflict of interest and funding

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.

References

- Allumbaugh D. L., Hoyt W. T. Effectiveness of grief therapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:370–380. [Google Scholar]

- Boelen P. A., De Keijser J., Van den Hout M. A., Van den Bout J. Treatment of complicated grief: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counselling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:277–284. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen P. A., Van den Bout J. Complicated grief, depression, and anxiety as distinct postloss syndromes: Aconfirmatory factor analysis study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:2175–2177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen P. A., Van den Hout M. A., Van den Bout J. The factor structure of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder symptoms among bereaved individuals: A confirmatory factor analysis study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno G. The other side of sadness. New York: Basic Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M., Cohen L. R., Koenen K. C. Treating survivors of childhood abuse. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M., Koenen K. C., Cohen L. R., Han H. Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1067–1074. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A., Mannarino A. P., Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Currier J. M., Neimeyer R. A., Berman J. S. The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for bereaved persons: A comprehensive quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:648–661. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daldrup R. J., Beutler L. E., Engle D., Greenberg L. S. Focused expressive psychotherapy: Freeing the overcontrolled patient. New York: Guilford Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R. SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual for the R (evised) Version. Baltimore: John Hopkins University School of Medicine; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A. Posttraumatische Belastungsstörung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. B., Rothbaum B. O. Treating the trauma of rape. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fortner B. V. The effectiveness of grief counseling and therapy: A quantitative review. Memphis: University of Memphis; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa D., Miyashita M., Nakajima S., Ito M., Kato M., Kimet Y. Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;127:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersons B. P. R., Carlier I. V. E., Lamberts R. D., Van der Kolk B. A randomized clinical trial of brief eclectic psychotherapy in police officers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:333–347. doi: 10.1023/A:1007793803627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M. J., Siegel B., Holen A., Bonanno G., Milbrath C., Stinson C. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:904–910. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M. J., Siegel B., Holen A., Bonanno G. A., Milbrath C., Stinson C. H. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. Focus. 2003;1:290–298. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S. Traumatic Grief: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis Group; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kato P. M., Mann T. A synthesis of psychological interventions for the bereaved. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19:275–296. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersting A., Brähler E., Glaesmer H., Wagner B. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population based sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;131:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindauer R. J. L., Vlieger E. J., Jalink M., Olff M., Carlier I. V. E., Majoie C. B. M. L., et al. Effects of psychotherapy on hippocampal volume in out-patients with post-traumatic stress disorder: A MRI investigation. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maercker A., Forstmeier S., Enzler A., Krüsi G., Hörler E., Maier C., et al. Adjustment disorders, PTSD and depressive disorders in old age: Findings from a community survey. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maercker A., Znoj H. J. The younger sibling of PTSD: Similarities and differences between complicated grief and posttraumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2010;1:1–9. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v1i0.5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melges F. T., De Maso D. R. Grief-resolution therapy: Reliving, revising, and revisiting. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1980;34:51–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1980.34.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) London: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society; 2005. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 26. Retrieved September 14, 2011, from http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG026fullguideline.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross J. C., Goldfried M., editors. Handbook of psychotherapy integration. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson H. G., Frank E., Kasl S. V., et al. Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:22–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson H. G., Bierhals A. J., Kasl S. V., Reynolds C. F., Shear M. K., Day N., et al. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:616–623. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson H. G., Horowitz M. J., Jacobs S. C., Parkes C. M., Aslan M., Goodkin K., et al. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(8):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando T. A. Treatment of complicated mourning. Champaign: Research Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner R., Hagl M. EffectiveTreatmentsforgrief followingthelossofalovedone.Aliteraturereviewof treatmentstudieswithadults. [Was hilft bei Trauer nach interpersonalen Verlusten? Eine Literaturübersicht zu Behandlungsstudien bei Erwachsenen] Psychodynamische Psychotherapie. 2007;6:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner R., Kotoucova M., Prigerson H., Pfoh G. Treatment of comorbid complicated grief disorder: A randomized controlled clinical trial; in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner R., Kruse J., Hagl M. Quantitative and qualitative review of interventions for the bereaved; Stockholm: Paper presented at the 9th European Conference on Traumatic Stress (ECOTS); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner R., Lumbeck G., Geissner E. Evaluation of a group therapy intervention for comorbid complicated grief. Psychotherapy Research. 2011;21:210–218. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2010.545839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner R., Wagner B. Komplizierte trauer. In: Maercker A., editor. Therapie der Posttraumatischen Belastungsstörung. Berlin: Springer; 2009. pp. 441–456. [Google Scholar]

- Shear M. K., Frank E., Foa E., Cherry C., Reynolds C. F., Bilt J. V., et al. Traumatic grief treatment: A pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1506–1508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear M. K., Simon N., Wall M., Zisook S., Neimeyer R., Duan N., et al. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:103–117. doi: 10.1002/da.20780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K., Frank E., Houck P. R., Reynolds C. F. Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B., Knaevelsrud C., Maercker A. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. Death Studies. 2006;30:429–453. doi: 10.1080/07481180600614385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H. U., Pfister H. Diagnostisches Expertensystem für Psychische Störungen. DIA-X Interviews. Frankfurt: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wittouck C., Van Autreve S., De Jaegere E., Portzky G., Van Heeringen K. The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]