Abstract

Pregnancy is a state of oxidative stress, which becomes exaggerated under pathological conditions, such as preeclampsia, IUGR, diabetes and obesity, where placental mitochondrial dysfunction is observed. The majority of investigations utilize isolated mitochondria when measuring mitochondrial activity in placenta. However, this does not provide a complete physiological readout of mitochondrial function. This technical note describes a method to measure respiratory function in intact primary syncytiotrophoblast from human term placenta.

Keywords: placenta, mitochondria, trophoblast, oxygen consumption, hypoxia

Introduction

The placenta transports gases and nutrients between mother and fetus, and releases hormones that influence maternal metabolism and fetal growth and development [1]. The transport and endocrine functions are mainly carried out by the syncytiotrophoblast, formed by fusion of mononuclear cytotrophoblasts [2–3]. The increasing metabolic activity of placental mitochondria throughout gestation results in excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress [4–5], which becomes exaggerated in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia [6–7], IUGR [8–9], gestational diabetes[10] and maternal obesity [11–12]. Several lines of evidence indicate that placental mitochondrial dysfunction is central to these pathological conditions [13–14]. In addition to being a major site for ROS production, mitochondria also become a target for ROS-induced damage and can be severely compromised by prolonged oxidative stress. Thus, mitochondrial abnormalities and ROS formation could be part of a vicious cycle and represent a mechanism of placental dysfunction. Given the crucial roles of mitochondria in normal and complicated pregnancies, the importance of being able to comprehensively assess mitochondrial function cannot be overemphasized.

Most investigations use measurement of single mitochondrial enzymes as indices of mitochondrial function. However, this does not provide a complete physiological readout of mitochondria. Important concerns are the disruption of the mitochondrial three-dimensional network or reticular structure [15] and lack of interaction with other cellular compartments (e.g., sarcoplasmic reticulum, cytoskeleton, lipid droplets) following the isolation of mitochondria [16].

Recent evidence suggests that mitochondrial morphology is closely associated with various functional aspects [17]. As such, we postulate that standard mitochondrial isolation procedures could have quite dramatic effects on mitochondrial function.

The goal of the present work was to establish a method to measure mitochondrial respiratory function in intact syncytiotrophoblast cells from human term placenta. We profiled mitochondrial function under normal and hypoxic conditions using a XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer from Seahorse Bioscience.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Oligomycin, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone FCCP, and Antimycin A solutions were obtained from Seahorse (Billerica, MA) as the Mito Stress Test Kit; Desferrioxamine (DFO) was purchased from Sigma.

Cytotrophoblast preparation and culture

All tissues were collected after obtaining informed consent under a protocol approved by the UTHSCSA Institutional Review Board. Cytotrophoblasts were purified from the placenta of uncomplicated term pregnancies obtained immediately after c-section (in the absence of labor) as we have previously described [18] and plated in Seahorse XF 24 well plates.

Measurement of cellular energetics

Cellular energetics were measured using a Seahorse Bioscience XF24 extracellular flux analyzer as described previously [19]. Data are expressed as the rate of oxygen consumption (OCR) in pmol/min. Total cellular protein was measured following each experiment by the Bradford method to normalize mitochondrial oxygen consumption.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as means ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were performed with Student's t-test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction was used where appropriate. The null hypothesis was rejected when p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

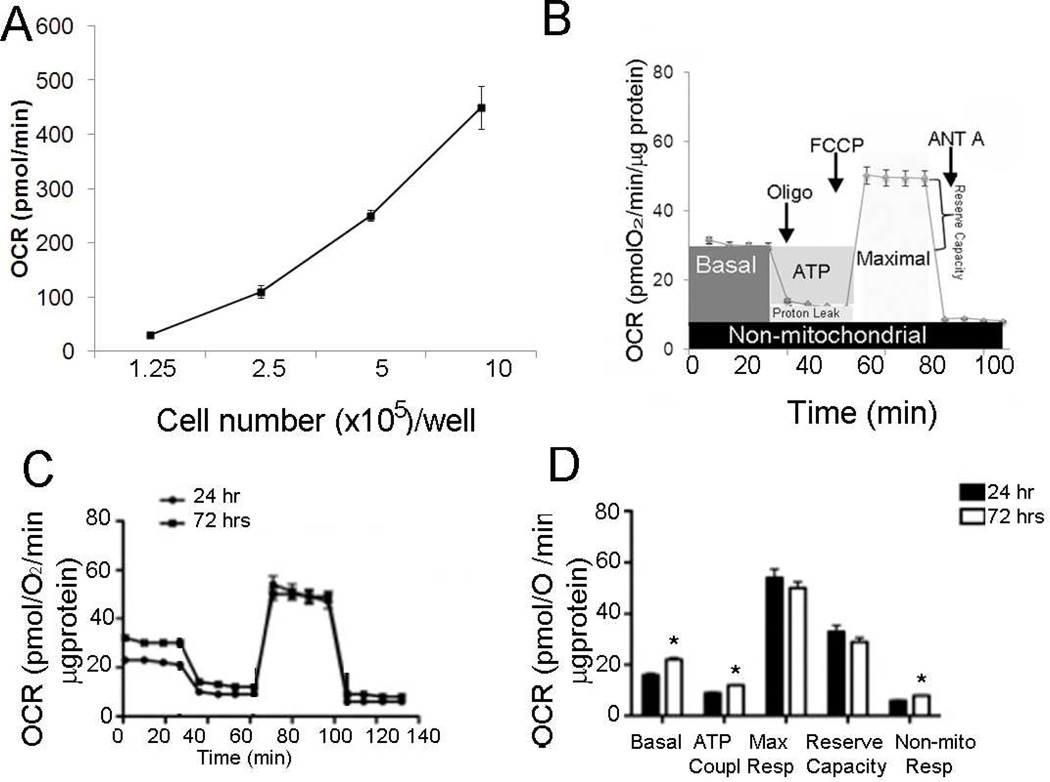

All cell cultures were predominantly trophoblast being 90–92% cytokeratin-18 positive and less than 9% positive for vimentin (data not shown). In the first series of experiments, the optimal number of cells needed to obtain a measurable and reproducible OCR was established. OCR increased with increasing cell number from 1.25×105 to 1×106 per well (Figure 1A), after which high variability in oxygen consumption and increased cell death were observed. A seeding density of 8×105 gave the best resolution for basal and maximal values of OCR and was chosen for the remainder of the experiments.

Figure 1.

A, Optimization of cell number for measuring OCR. Basal OCR was measured and plotted as a function of cell seeding number (triplicate measurements at each cell density taken from same culture of primary syncytiotrophoblasts and representative of 3 individual experiments).

B, Mitochondrial Stress Test. OCR was measured under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin (1 µg/ml), FCCP (1 µM), and antimycin A (10 µM), as indicated. Each data point represents an OCR measurement as mean ± SE (n=6 cultures of primary syncytiotrophoblast each from a different placenta).

C, D, Effect of syncytialization of cytotrophoblasts on mitochondrial respiration. C, OCR was measured by sequential addition of inhibitors as shown in panel B on single cytotrophoblast cells at 24 hrs and syncytialized trophoblasts at 72 hrs after plating. D, Individual parameters for basal respiration, ATP coupling, non-mitochondrial OCR, reserve capacity, and maximal respiration were derived from the assay in panel C, mean +/− SE, *p < 0.05 vs. 24 hours measurements, n=6 placentas.

In many studies with the XF24, a straightforward bioenergetic assay, a stress test, has been used [20–21]. This assay uses inhibitors of respiratory complexes and uncoupling agents to examine and quantify different components of mitochondrial function. The general scheme of stress test is shown in Figure 1B. To estimate the proportion of the basal OCR coupled to ATP synthesis, ATP synthase (Complex V) was inhibited by oligomycin (0.5 µM). It decreased the OCR rate to the extent to which the cells are using mitochondria to generate ATP. The remaining OCR is ascribed to proton leak across the mitochondrial membrane. To determine the maximal OCR that the cells can sustain, the proton ionophore FCCP (0.75 µM) was injected. Lastly, antimycin A (1.5 µM) was injected to inhibit electron flux through Complex III which causes a dramatic suppression of the OCR. The remaining OCR is attributable to O2 consumption due to the formation of mitochondrial ROS and non-mitochondrial sources. The reserve respiratory capacity was calculated as the maximal rate minus the basal rate and presents a parameter which is available to cells for increased work to cope with stress.

To assess the effect of syncytialization on cellular energetics, the stress test was performed as described on both single cytotrophoblasts 24 hours after plating and syncytiotrophoblast at 72hr (Fig. 1C), and individual parameters were calculated (Fig.1D). Syncytiotrophoblasts showed significantly higher levels of basal and non-mitochondrial respiration, and ATP coupling when compared to cytotrophoblasts but with no change in maximal respiration and reserve capacity.

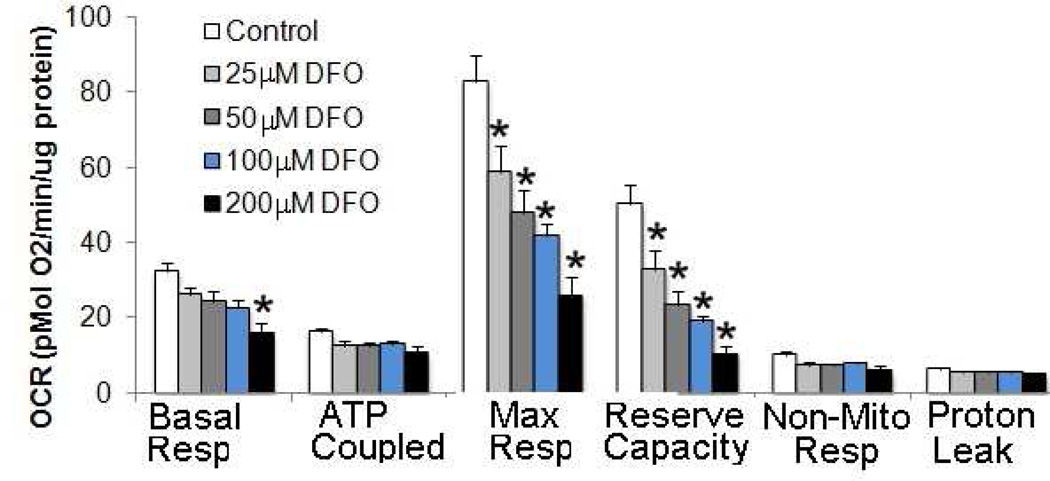

Finally, we examined the effects of chemically-induced hypoxia on mitochondrial bioenergetics by exposing the cells for 24 hours to different concentrations of the iron chelating agent desferrioxamine (DFO), which induces the accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protein [22–24] (Fig. 2). DFO treatment significantly reduced the maximal flux through electron transport chain in a concentration-dependent manner from 25µM to 200 µM. The trophoblasts exposed to DFO maintained, however, the basal (up to 200µM of DFO) and ATP-linked oxygen consumption.

Figure 2. Effect of addition of Desferrioxamine (DFO) on mitochondrial function.

Cytotrophoblasts were seeded at 8×105 cells/well in Seahorse XF 24 well plates. DFO treatment was initiated at 42 hrs after plating, continued for 24 hrs and cell bioenergetics analyzed by XF 24. Following basal OCR readings, OCR was measured with oligomycin (0.5 µM), FCCP (0.75 µM) and Antimycin A (1.5 µµM), n=6 cultures of primary syncytiotrophoblast each comes from a different placenta), *p<0.005 vs. untreated control.

In summary, we showed here that the XF24 extracellular flux analyzer presents a reliable tool to address a number of questions related to placental mitochondrial competence.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Myatt L. Placental adaptive responses and fetal programming. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 1):25–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.104968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kliman HJ, et al. Purification, characterization, and in vitro differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from human term placentae. Endocrinology. 1986;118(4):1567–1582. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-4-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringler GE, Strauss JF., 3rd In vitro systems for the study of human placental endocrine function. Endocr Rev. 1990;11(1):105–123. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-1-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llurba E, et al. A comprehensive study of oxidative stress and antioxidant status in preeclampsia and normal pregnancy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37(4):557–570. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson AL, et al. Susceptibility of human placental syncytiotrophoblastic mitochondria to oxygen-mediated damage in relation to gestational age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(5):1697–1705. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Walsh SW. Placental mitochondria as a source of oxidative stress in preeclampsia. Placenta. 1998;19(8):581–586. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(98)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myatt L. Review: Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and functional adaptation of the placenta. Placenta. 2010;31(Suppl):S66–S69. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lattuada D, et al. Higher mitochondrial DNA content in human IUGR placenta. Placenta. 2008;29(12):1029–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valsamakis G, et al. Causes of intrauterine growth restriction and the postnatal development of the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1092:138–147. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera E, Ortega-Senovilla H. Disturbances in lipid metabolism in diabetic pregnancy - Are these the cause of the problem? Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24(4):515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts VH, et al. Effect of increasing maternal body mass index on oxidative and nitrative stress in the human placenta. Placenta. 2009;30(2):169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poston L, et al. Role of oxidative stress and antioxidant supplementation in pregnancy disorders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widschwendter M, Schrocksnadel H, Mortl MG. Pre-eclampsia: a disorder of placental mitochondria? Mol Med Today. 1998;4(7):286–291. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burton GJ. Oxygen, the Janus gas; its effects on human placental development and function. J Anat. 2009;215(1):27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogata T, Yamasaki Y. Ultra-high-resolution scanning electron microscopy of mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticulum arrangement in human red, white, and intermediate muscle fibers. Anat Rec. 1997;248(2):214–223. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199706)248:2<214::AID-AR8>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saks V, et al. Structure-function relationships in feedback regulation of energy fluxes in vivo in health and disease: mitochondrial interactosome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(6–7):678–697. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hom J, Sheu SS. Morphological dynamics of mitochondria--a special emphasis on cardiac muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46(6):811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eis AL, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in human villous and extravillous trophoblast populations and expression during syncytiotrophoblast formation in vitro. Placenta. 1995;16(2):113–126. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(95)90000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholls DG, et al. Bioenergetic profile experiment using C2C12 myoblast cells. J Vis Exp. 2010;(46) doi: 10.3791/2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi SW, Gerencser AA, Nicholls DG. Bioenergetic analysis of isolated cerebrocortical nerve terminals on a microgram scale: spare respiratory capacity and stochastic mitochondrial failure. J Neurochem. 2009;109(4):1179–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sansbury BE, et al. Bioenergetic function in cardiovascular cells: the importance of the reserve capacity and its biological regulation. Chem Biol Interact. 2011;191(1–3):288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An WG, et al. Stabilization of wild-type p53 by hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Nature. 1998;392(6674):405–408. doi: 10.1038/32925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coma S, Shimizu A, Klagsbrun M. Hypoxia induces tumor and endothelial cell migration in a semaphorin 3F- and VEGF-dependent manner via transcriptional repression of their common receptor neuropilin 2. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5(3):266–275. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.3.16294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mordente A, et al. Prooxidant action of desferrioxamine: enhancement of alkaline phosphatase inactivation by interaction with ascorbate system. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;277(2):234–240. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90574-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]