Abstract

Objective

Brain computer interface (BCI) systems have emerged as a method to restore function and enhance communication in motor impaired patients. To date, this has been primarily applied to patients who have a compromised motor outflow due to spinal cord dysfunction, but an intact and functioning cerebral cortex. The cortical physiology associated with movement of the contralateral limb has typically been the signal substrate that has been used as a control signal. While this is an ideal control platform in patients with an intact motor cortex, these signals are lost after a hemispheric stroke. Thus, a different control signal is needed that could provide control capability for a patient with a hemiparetic limb. Previous studies have shown that there is a distinct cortical physiology associated with ipsilateral, or same sided, limb movements. Thus far, it was unknown whether stroke survivors could intentionally and effectively modulate this ipsilateral motor activity from their unaffected hemisphere. Therefore, this study seeks to evaluate whether stroke survivors could effectively utilize ipsilateral motor activity from their unaffected hemisphere to achieve this BCI control.

Approach

To investigate this possibility, electroencephalographic (EEG) signals were recorded from four chronic hemispheric stroke patients as they performed (or attempted to perform) real and imagined hand tasks using either their affected or unaffected hand. Following performance of the screening task, the ability of patients to utilize a BCI system was investigated during on-line control of a 1-dimensional control task.

Main Results

Significant ipsilateral motor signals (associated with movement intentions of the affected hand) in the unaffected hemisphere, which were found to be distinct from rest and contralateral signals, were identified and subsequently used for a simple online BCI control task. We demonstrate here for the first time that EEG signals from the unaffected hemisphere, associated with overt and imagined movements of the affected hand, can enable stroke survivors to control a one-dimensional computer cursor rapidly and accurately. This ipsilateral motor activity enabled users to achieve final target accuracies between 68 and 91% within 15 minutes.

Significance

These findings suggest that ipsilateral motor activity from the unaffected hemisphere in stroke survivors could provide a physiological substrate for BCI operation that can be further developed as a long-term assistive device or potentially provide a novel tool for rehabilitation.

Keywords: Electroencephalography, EEG, Ipsilateral, Motor, Brain Computer Interface, Neuroprosthetics, Stroke, Hemiplegia, BCI

1. Introduction

Currently a challenge in the treatment of stroke survivors is the rehabilitation of chronically lost motor functions. Several studies describing hemiparesis in chronic stroke survivors demonstrate that motor recovery plateaus 3 months post-stroke (Duncan, Goldstein et al. 1992; Jorgensen, Nakayama et al. 1995; Lloyd-Jones, Adams et al. 2009). A potential novel approach for the restoration of function and improving the quality of life of these patients could be the use of a brain computer interface (BCI). These systems use signals recorded from the central nervous system as a control signal for operating a computer or other device. Restoring function could be accomplished either through controlling an assistive device independent of the unaffected hand, or through paired BCI control and peripheral stimulation to induce functional recovery through endogenous plasticity. Thus far, substantial research has shown that information from motor cortex contralateral to an intended limb encodes useful information about motor intent and can be used to control multiple degree-of-freedom BCI systems with a variety of recording modalities (Taylor, Tillery et al. 2002; Leuthardt, Schalk et al. 2004; Wolpaw and McFarland 2004; Hochberg, Serruya et al. 2006; Schalk, Miller et al. 2008; Velliste, Perel et al. 2008; Rouse and Moran 2009). While these physiologic signals are useful in controlling BCI systems designed for motor impaired patients with intact cortex (Pfurtscheller, Guger et al. 2000; Taylor, Tillery et al. 2002; Wolpaw and McFarland 2004; Kubler, Nijboer et al. 2005; Hochberg, Serruya et al. 2006), a different cortical signal would be necessary in hemiplegic stroke survivors that suffer damage to primary motor cortex contralateral to the affected limb. This is important both in a traditional BCI device (which enables brain-derived control of an assistive machine) and also in potentially encouraging functional rehabilitation (to facilitate endogenous recovery of limb function). Taken together, there is a substantive need to develop new methods for restoring function in chronic hemiplegic stroke survivors, which may be accomplished through utilizing novel cortical control signals in conjunction with a BCI system.

Recent work by Wisneski et al. has demonstrated a separable and distinct cortical physiology associated with ipsilateral hand movements (i.e. movements on the same side as the respective hemisphere) that can be distinguished from cortical signals associated with movement contralateral to a given hemisphere (2008). Electrocorticographic (ECoG) signals were recorded while subjects engaged in specific ipsilateral or contralateral hand motor tasks. Ipsilateral hand movements were associated with electrophysiological changes that occurred in lower frequency spectra (average 37.5Hz), at distinct anatomic locations (most notably in premotor cortex), and earlier (by 160 ms) than changes associated with contralateral hand movements. Given that these cortical changes occurred earlier and were localized preferentially in premotor cortex compared to those associated with contralateral movements, the authors postulated that ipsilateral cortex is more associated with motor planning than its execution. Furthermore, while rehabilitation from stroke has traditionally been viewed as a “perilesional awakening” of cortex (Weiller, Chollet et al. 1992; Tecchio, Zappasodi et al. 2006), recent studies in stroke survivors have shown that the potential for recovery is inversely correlated to corticospinal tract damage (Carter, Patel et al. 2011). While in general outcome is better when perilesional activity produces a more normal pattern of contralateral activation is restored after stroke (Ward, Brown et al. 2003; Ward, Brown et al. 2003), this often may not occur because of the severity of the injury to the corticospinal tract or cortex. Furthermore, ipsilateral activity has been shown to play a role in the planning of arm movements (Schaefer, Haaland et al. 2009; Schaefer, Haaland et al. 2009), and activity from the ipsilateral unaffected hemisphere has been shown to increase with increases in functional outcome in some patients (Cramer, Nelles et al. 1997; Tecchio, Zappasodi et al. 2006). Therefore, the unaffected hemisphere would provide an alternative pathway, allowing it to play a compensatory role in motor control in people with severe lesions. Additionally, it has been shown in hemiplegic stroke survivors that ipsilateral motor activity is independent of contralateral motor activity and that affected and unaffected limb movements can be discriminated from neural activity in a single hemisphere (Cramer, Mark et al. 2002). Taken together, these indicate that 1) there is a separable physiology associated with actively planning and executing ipsilateral hand movements and 2) that this physiology appears to be involved in the functional reorganization of unaffected cortex and represents an alternative pathway that may facilitate some level of recovery in patients with large cortical lesions or lesions transecting the corticospinal tract.

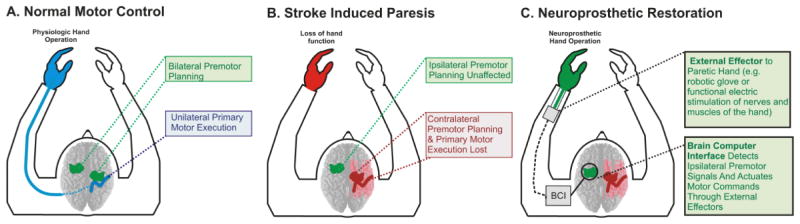

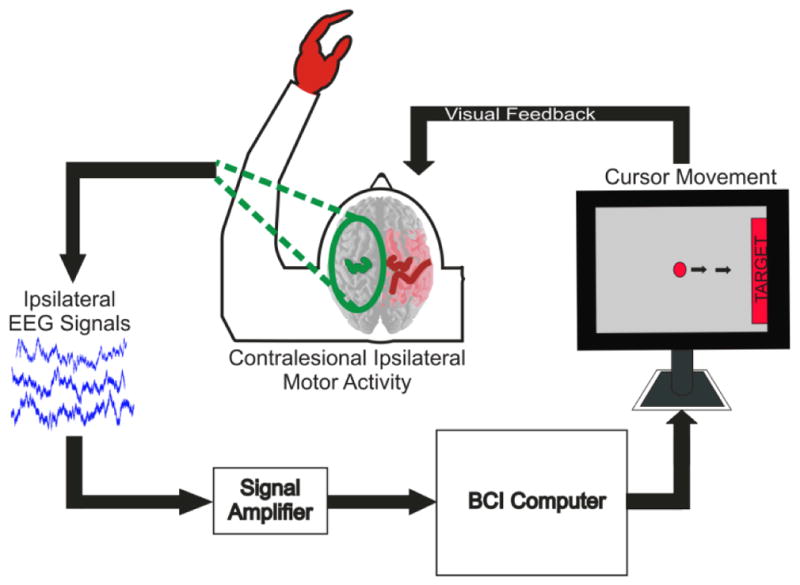

In the past, a few case studies have demonstrated the use of BCI systems utilizing perilesional cortex contralateral to the affected limb in individual stroke survivors (Buch, Weber et al. 2008; Daly, Cheng et al. 2009; Broetz, Braun et al. 2010). This project, however, sought to develop a wholly new approach by creating a contralesional BCI in stroke survivors. In this study, we examined whether the physiology associated with ipsilateral hand movements could be used as a control signal for a BCI in hemispheric stroke patients (Figure 1). Because brain signals were found to be optimal below 40 Hz and located in more prefrontal regions, we hypothesized that these signals would be accessible with electroencephalography (EEG) and provide sufficient information to control a simple device. We demonstrate for the first time that this ipsilateral cortical physiology can be effectively used to control a cursor in a one-dimensional control task. These findings support the feasibility of using brain signals from the unaffected hemisphere as a signal platform in the setting of unilateral stroke for potential functional restoration. This approach is especially salient in dense hemiplegics for whom there is an absence of rehabilitation options or alternatives because they have minimal functional capacity to participate in current rehabilitation paradigms.

Fig. 1. Conceptual schematic of ipsilateral BCI using the unaffected hemisphere.

After a hemispheric stroke, motor impaired stroke survivors will have damage to the contralateral primary and premotor cortices or their associated subcortical pathways. In order to implement a BCI system, we propose that an effective alternative control signal is the ipsilateral premotor planning region in the unaffected hemisphere.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

This study utilized four chronic first time (17–53 months post-stroke) hemispheric stroke survivors (age 48–61). Exclusion criteria included prior strokes. Additionally strokes that resulted in dementia, inattention, or aphasia, which would prevent subjects from performing the required cognitive tasks, were also excluded. The study was approved by the Human Research Protection Organization of the Washington University Medical Center. Prior to inclusion in the study, subjects provided their written informed consent. Subjects were enrolled from a previous study (Carter, Astafiev et al. 2010; Carter, Patel et al. 2011), which provided data on lesion localization and chronic functional evaluation. Prior to enrollment in the study, lesion locations and functional motor evaluations were considered from over 40 potential subjects. The 4 subjects utilized were selected considering the exclusion criteria as well as the fact that more severely impaired patients represent the population more likely to benefit from BCI applications. Before this study, subjects had no prior training on the use of a BCI system. Demographic and clinical information for each of the four subjects is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information for the four subjects.

| Patient | Age | Sex | Time from stroke (mos.) | Lesion Hemisphere | Lesion Location | ChronicMotor Function Evaluation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARAT Contra Total | ARAT Contra Grasp | ARAT Contra Grip | ARAT Contra Pinch | ARAT Contra Gross | Contra Grip Strength | Ipsi Grip Strength | Clinical Hand Strength | ||||||

| 1 | 48 | M | 53 | Right | Middle Cerebral Artery | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4/5 Contra;5/5 Ipsi |

| 2 | 65 | F | 17 | Right | Middle Cerebral Artery | 0/65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| 3 | 54 | F | 26 | Left | Scattered Lacunar | 41/65 | 13 | 12 | 13 | 3 | 1.3 kg | 19.7 kg | - |

| 4 | 61 | M | 20 | Left | Middle Cerebral Artery | 30/65 | 18 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4.7 kg | 30.7 kg | - |

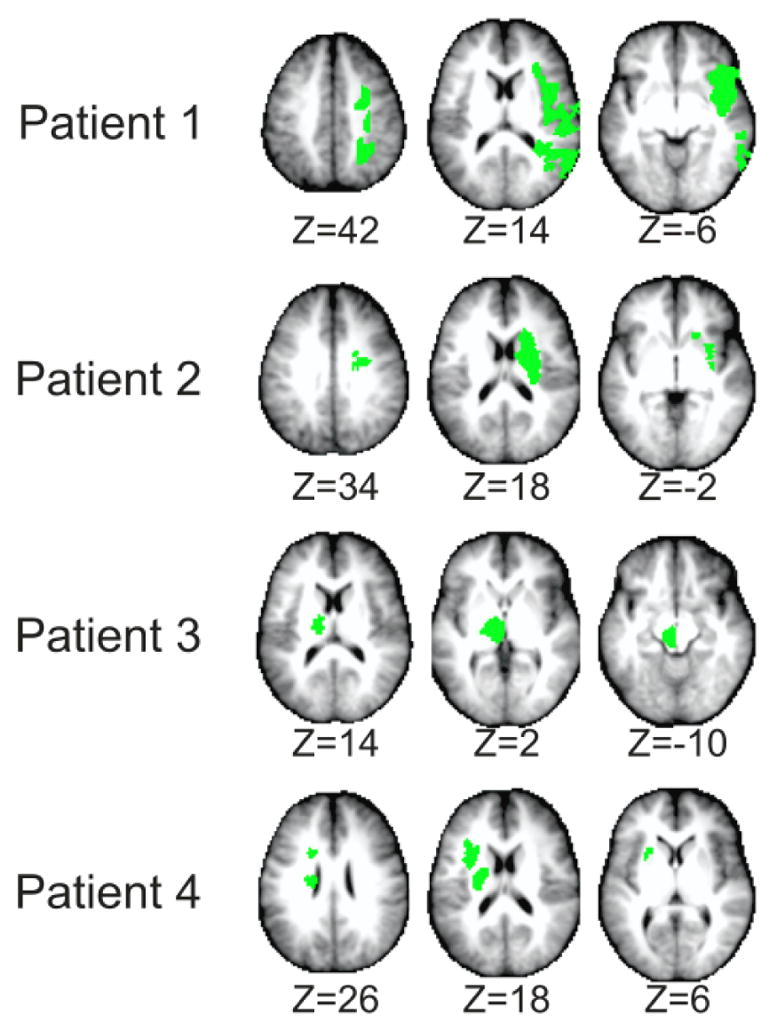

2.2 Lesion Segmentation

Segmentation of stroke lesions was performed as described in Carter et al. using T1-weighted MP-RAGE and T2-weighted spin echo images (Carter, Astafiev et al. 2010). Voxels were categorized into air, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), gray matter, and white matter by an unsupervised fuzzy class means-based segmentation. Expert judgment was used to determine the boundary between CSF and lesioned parenchyma. Figure 2 shows the location and extent of lesions in each subject.

Fig. 2. Lesion characteristics.

Lesion locations segmented from T1-weighted MP-RAGE and T2-weighted spin echo images. Selected axial slices show upper, intermediate, and lower areas of the lesion (Left-on-left orientation).

2.3 EEG Recordings

In all subjects, EEG was recorded from 33 (Patients 1 and 2) or 45 (Patients 3 and 4) scalp locations over frontal and parietal regions within the 10–20 system of electrode locations. Recording locations were channel positions AF5, AF3, AFZ, AF4, AF6, F5, F3, F1, FZ, F2, F4, F6, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCZ, FC2, FC4, FC6, C5, C3, C1, CZ, C2, C4, C6, CP5, CP3, CP1, CPZ, CP2, CP4, CP6 (all patients) and P5, P3, P1, PZ, P2, P4, P6, PO5, PO3, POZ, PO4, PO6 (Patients 3 and 4 only). Recordings were digitized using 16-channel digital amplifiers (g.USBamp, g.tec, Austria). The left and right ear lobes were used as the ground and reference respectively. Signals were spatially filtered using a bipolar derivation to enhance the spatial specificity of recordings. Recordings were sampled at 256 Hz (subjects 1 and 2) or 512 Hz (subjects 3 and 4) and were high-pass filtered at 0.1 Hz prior to analysis. A Dell computer running the BCI2000 software platform was used to acquire, process, and store the EEG data for real-time stimulus presentation and time-locked acquisition and analysis of brain signals (Schalk, McFarland et al. 2004).

2.4 Control Feature Screening

Initially, subjects underwent screening to identify features of cortical activity to be used in subsequent closed-loop BCI control experiments. This procedure involved an experiment in which EEG signals were recorded while the subject performed overt or imagined self-timed, self-selected finger-tapping movements of the right or left hand in isolation from the opposite hand, or rested. Cues for the rest and finger movement conditions were presented as words (‘Right’, ‘Left’) and a fixation cross (Rest) on a computer screen that was placed approximately 75cm in front of the subject. For the overt movement condition, subjects with residual function in their affected hand (Patient 1) were instructed to perform overt movements of both hands, while those with less function in the affected hand were instructed to perform overt movements of the unaffected hand and intended movements of the affected hand. In a second screening task, all subjects were instructed to perform imagined movements of both the affected and unaffected hands. Cues were presented in a random order with each stimulus presented for a period of 2.5s. Subjects were instructed to perform the specified action for the duration of the stimulus presentation. In subjects with chronic hemiplegia preventing individual finger movements of the affected hand (subjects 2, 3, and 4) the subjects were instructed to overtly move their unaffected hand and imagine similar movements of the affected hand during the respective stimulus periods. All subjects performed the overt movement task initially while being observed for successful task performance, followed by performance of the imagined movement task.

EEG data collected during the experiment were converted from the time domain to the frequency domain using the maximum entropy method for autoregressive spectral estimation (Marple 1987). Power spectra were estimated in 2 Hz bins ranging from 1 to 55 Hz. Candidate features were identified by calculating the signed coefficient of determination (r2) between the ‘rest’ interval spectral power levels and the affected hand movement spectral power levels. EEG features in particular electrodes and frequency bands with the greatest percentage of their variance explained by the task (i.e. the highest r2 values), were chosen as candidate control features for closed-loop BCI experiments. Selection of candidate control features was also further constrained to contain only electrodes over the unaffected hemisphere during movement or imagined movement of the affected hand. Where possible, candidate features were selected to discriminate affected hand movement from rest as well as affected hand movement from unaffected hand movement.

2.5 Closed-loop BCI Evaluation

After determining candidate EEG control features associated with intended movement of the affected hand using the screening procedure described previously, subjects participated in closed-loop BCI control evaluation (see Figure 3). For this evaluation, the subjects’ objective was to perform intended movements of the affected hand in order to hit a target with a cursor. The target was presented on either the right or left side of a screen and the cursor moved along a single dimension. Several control scenarios were tested; (1) overt movement of the affected hand versus rest (Patient 1), (2) intended movement of the affected hand versus rest (Patients 2, 3, and 4), and (3) imagined movement of the affected hand versus imagined movement of the unaffected hand (Patients 1 and 2). The various closed-loop control conditions used depended upon the discriminability of control features as well as patient attention and fatigue. The velocity of the cursor was calculated from the real-time EEG features through the BCI2000 software package. The change in power from baseline of the selected EEG features (i.e. the power in the selected frequency bin(s) at the selected electrode location(s) over the unaffected hemisphere) were weighted and summed to allow the patient to control the cursor. As all of the features identified for these subjects were power decreases, they were weighted negatively so the task-related score increased with task-related power decreases. The feature power levels were translated into the cursor score through BCI2000 (Schalk, McFarland et al. 2004). In order to normalize the weighted and summed power levels, the normalizer was trained using several trials in each target direction in which the subject attempted to perform the selected control task (i.e. affected hand movement, resting) in order to control the cursor. The mean of the weighted and summated features was calculated after the training period (1–2 minutes) and was used to normalize the scores to have zero mean. The normalized score was then used to control the cursor velocity. The velocity of the cursor was updated every 40 ms based upon spectra estimated from an autoregressive method using data acquired over the previous 280 ms. Subjects performed consecutive trials in which they attempted to move the cursor to the presented target. Each trial began with the presentation of a target randomly selected to be at either the right or left side of the screen. After a 1 s delay, the cursor appeared in the middle of the screen with its motion in the horizontal dimension controlled by the subject’s EEG signals. The subject was instructed to begin performing the particular hand movement task or rest condition to move the cursor to the selected target as soon as the target appeared on the screen. Each trial was assessed as a success (cursor hit the selected target), or failure (cursor hit the opposite target or time ran out before success occurred, 6–10s). Trials were grouped into runs of 2 min with rest periods of approximately 1 min in between runs. The accuracy was assessed as the number of successful trials divided by the total number of trials at the end of each run. The development of BCI control over time was assessed by comparing the accuracy at the end of each consecutive run after training with a particular task and associated EEG control features. Because each trial did not have to result in a target being hit, chance was not necessarily 50%. As described previously by Leuthardt et. al., chance performance was determined by running multiple runs of control trials using Gaussian white noise signals yielding a mean chance performance of 46.2% (2.7% SD) (Leuthardt, Gaona et al. 2011). Subjects performed between 85 and 246 control trials.

Fig. 3. Closed loop control with ipsilateral motor signals.

Experimental setup for closed-loop control task. On screen cursor moves toward target with performance of appropriate intended motor movement. Cursor movement is determined by pre-screened control features from the EEG signals recorded from the subject’s unaffected hemisphere.

3. Results

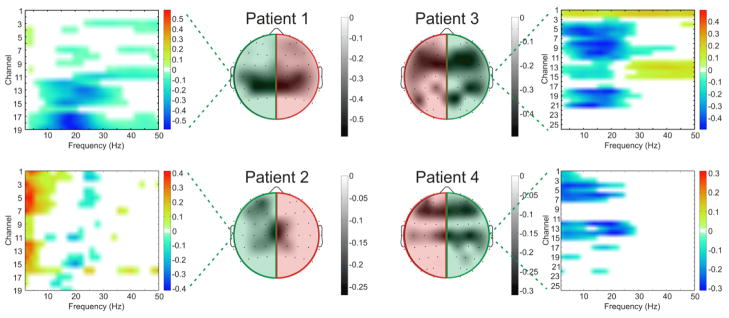

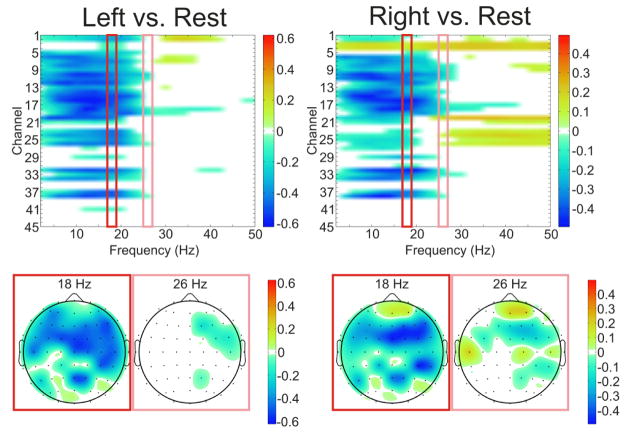

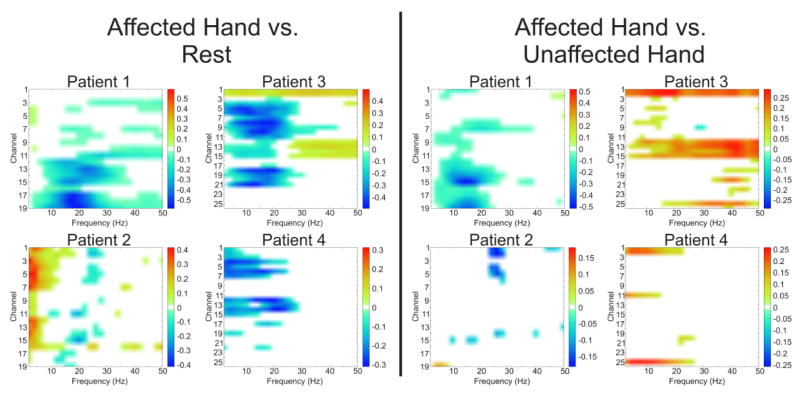

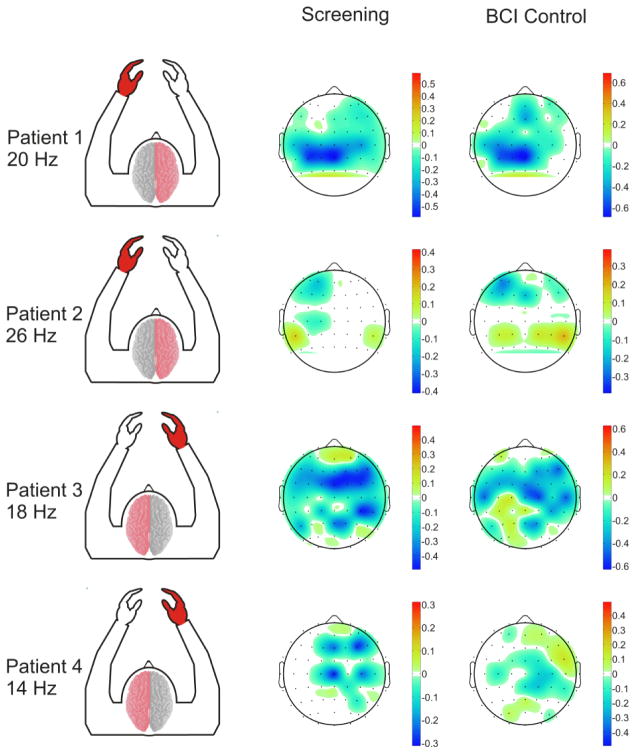

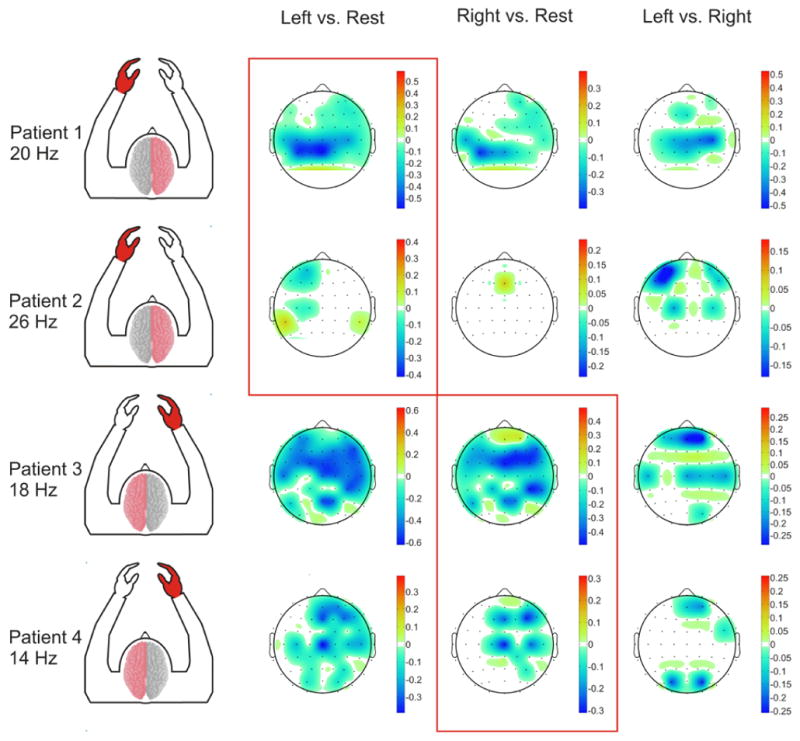

Each subject demonstrated cortical activations in the unaffected hemisphere associated with intended movement of the affected hand. Figure 4 displays that for each subject there was a cortical activation ipsilateral to the side of intended movement of the affected hand (within the unaffected hemisphere). Notably, consistent with Wisneski el al., when compared to cortical activations in the unaffected hemisphere associated with movement intentions of the unaffected hand (i.e. contralateral movements) there were notable differences in frequency spectra and anatomic locations (Wisneski, Anderson et al. 2008). Figure 5 illustrates this spectral distinction in cortical activity within a single exemplar subject (patient 3). In this subject, the topography at 18 Hz is broad and fairly similar between ipsilateral and contralateral movement, while there are distinct differences in topography at the higher beta (26 Hz) and low gamma (>30 Hz) frequencies. Most notably there is a more extensive activation in the prefrontal region (in the left unaffected hemisphere) that demonstrates a 26 Hz power modulation with ipsilateral right hand movement that is not present with contralateral left hand movement. Moreover, when examining all subjects, various locations and EEG frequencies separated intended affected hand movements both from rest and from unaffected hand movements (Figure 6). The locations that optimally separated ipsilateral from contralateral intentions in the unaffected hemisphere were located both over traditional sensorimotor regions, as well as more anterior areas associated with premotor planning. Furthermore, qualitatively it was observed that subjects with more severe motor impairments demonstrate a more anterior shift in the activations within the unaffected hemisphere associated with intended movement of the ipsilateral affected hand. This shift in ipsilateral activity is similar to the anterior and ventral shift in ipsilateral activity shown by Cramer et al. with fMRI (Cramer, Finklestein et al. 1999).

Fig. 4. Topography of screening task activations.

Topographical maps of the maximum coefficient-of-determination of significant (p<0.05) event-related power decreases between 0 Hz and 50 Hz for affected hand movement vs. rest conditions in each patient. As power decreases cause more negative signed r2 values, more negative areas in the topographic activations represent increased neural activity. Green and red highlighting on the topographic plots illustrates the unaffected and affected hemisphere in each patient respectively. Feature plots demonstrate significant ipsilateral coefficient-of-determination values from the unaffected hemisphere across the frequency spectrum, illustrating that the cortical activations are observed across the frequency spectrum, but particularly in the mu (8–12 Hz) and beta (12–30 Hz) bands. Channels displayed on the feature plots correspond to electrode positions AF5, AF3, AFZ, F5, F3, F1, FZ, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCZ, C5, C3, C1, CZ, CP5, CP3, CP1, CPZ (Patients 1 and 2) and AFZ, AF4, AF6, FZ, F2, F4, F6, FCZ, FC2, FC4, FC6, CZ, C2, C4, C6, CPZ, CP2, CP4, CP6, PZ, P2, P4, P6, POZ, PO4, PO6 (Patients 3 and 4).

Fig. 5. Spectral specificity of neural activity within an exemplar patient.

Feature plots demonstrating the frequency specificity of movements of the affected (right) and unaffected (left) hands in an exemplar subject who had stroke affecting the left hemisphere (Patient 3). The topography at 18 Hz is broad and fairly similar between the two conditions, while there are distinct differences in topography at the higher beta (26 Hz) frequency. Channel numbers correspond to electrode locations AF5, AF3, AFZ, AF4, AF6, F5, F3, F1, FZ, F2, F4, F6, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCZ, FC2, FC4, FC6, C5, C3, C1, CZ, C2, C4, C6, CP5, CP3, CP1, CPZ, CP2, CP4, CP6, P5, P3, P1, PZ, P2, P4, P6, PO5, PO3, POZ, PO4, PO6.

Fig. 6. Spectral specificity differentiates movement conditions across subjects.

Feature plots demonstrate significant (p<0.05) r2 values differentiating affected hand movements from rest (left plots) and affected hand movement from unaffected hand movements (right plots) based upon electrodes located over the unaffected hemisphere. All four patients show significant decreases in power related to intended movement of the ipsilateral, unaffected hand. Additionally, 3 of the 4 patients have unique spatial and spectral activations differentiating affected hand and unaffected hand movements within the unaffected hemisphere either through decreases in power in the alpha (9–12Hz) or Beta (12–30Hz) bands (Patients 1 and 2) or increases in gamma band (>30 Hz) power (Patient 3). Channels displayed correspond to electrode positions AF5, AF3, AFZ, F5, F3, F1, FZ, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCZ, C5, C3, C1, CZ, CP5, CP3, CP1, CPZ (Patients 1 and 2) and AFZ, AF4, AF6, FZ, F2, F4, F6, FCZ, FC2, FC4, FC6, CZ, C2, C4, C6, CPZ, CP2, CP4, CP6, PZ, P2, P4, P6, POZ, PO4, PO6 (Patients 3 and 4).

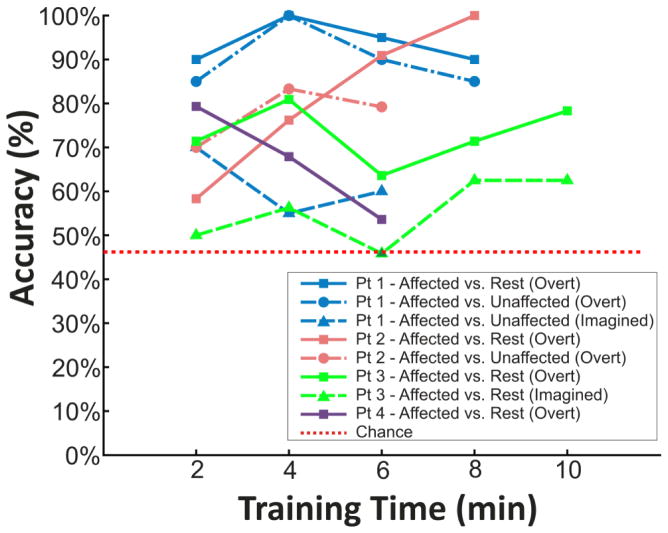

Select features were then identified for subsequent online BCI operation. Figure 7 illustrates the significant (p<0.05) activations differentiating movements of the affected hand from rest, the unaffected hand from rest, and the affected hand from the unaffected hand at frequencies utilized for subsequent BCI control by each patient. The time course of each subject’s performance during closed-loop BCI control is shown in Figure 8. Peak target accuracies for all subjects were all between 62.5% and 100% and final accuracies for all subjects were between 53.6% and 100% and therefore were all above chance (46.2%, 2.7% SD). This level of performance was achieved in BCI control experiments with durations ranging from 6 to 10 min. Table 2 summarizes the activities utilized for BCI control, the EEG features used, and the peak and final BCI accuracy achieved by the subject.

Fig. 7. Topography of screening task activations.

Topographical maps of significant (p<0.05) coefficient of determination values from the motor screening task in all patients. The stroke injured hemisphere and affected hand area are labeled in red. Frequency bands shown correspond to those utilized in each patient’s respective closed-loop BCI control experiments. All subjects demonstrated significant activations related to intended movements of their affected hand in their unaffected hemisphere (highlighted within the red boxes).

Fig. 8. Learning curves for BCI control tasks.

All subjects achieved peak accuracies greater than 62.5% with only 6 to 10 minutes of training time.

Table 2.

Closed Loop BCI Performance Data.

| Subject | Task (Direction) | EEG Channels | Frequency Used | Peak Accuracy | Final Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Affected Hand (Left) vs. Rest (Right) Overt. | CP3, CP1 | 18 – 22 Hz | 100% | 90% |

| Affected Hand (Left) vs. Unaffected Hand (Right) Overt | C1 | 12 – 18 Hz | 100% | 85% | |

| Affected Hand (Left) vs. Unaffected Hand (Right) Imagined | C1 | 12 – 18 Hz | 70% | 60% | |

| 2 | Affected Hand (Left) vs. Rest (Right) Overt | AF5, AF3, F3, F1 | 24 – 28 Hz | 100% | 100% |

| Affected Hand (Left) vs. Unaffected Hand (Right) Overt | AF5, AF3, F3, F1 | 24 – 28 Hz | 83.3% | 79% | |

| 3 | Affected Hand (Right) vs. Rest (Left) Overt | FC2, FC4 | 16 – 18 Hz | 80.9% | 78.3% |

| Affected Hand (Right) vs. Rest (Left) Imagined | FC2, FC4 | 16 – 18 Hz | 62.5% | 62.5% | |

| 4 | Affected Hand (Right) vs. Rest (Left) Overt | CP2, F2 | 12 – 14 Hz | 79.3% | 53.6% |

The EEG recordings from the closed-loop control experiments were also examined post-hoc to compare the cortical activations associated with the screening task to those associated with the closed-loop task. The activations in the selected EEG control frequency for the affected hand movement versus rest conditions are shown for both the screening and control experiments in Figure 9. As can be seen, there is good correspondence between the topographies of the activations during the control and screening task, indicating that the successful BCI control performance was achieved through performance of the intended motor task and not a spurious or alternative strategy. Furthermore, correlations between the topography of activations in the selected control frequency between screening and control tasks (patient 1: R=0.82, p<0.0001; patient 2: R=0.6108, p=0.0002; patient 3: R=0.7098, p<0.0001; patient 4: R=−0.0194; P=0.8994) were highly significant in 3 of the 4 subjects. The discrepancy in patient 4 can be attributed to the patient tiring towards the end of the session, likely leading to changes to cortical activations due to decreases in attention to the task. This decrease in attention and different neural activity would also explain the fact that patient 4 demonstrated poorer peak and final BCI control accuracies than the other 3 subjects.

Fig. 9. Comparison of neural activity during screening and BCI control.

Significant (p<0.05) coefficient of determination values for affected hand vs. rest conditions during motor screening and control tasks. The stroke injured hemisphere and affected hand area labeled in red. Selected frequencies were utilized for overt/intended affected hand vs. rest control in each patient. Patients exhibit similar topographies of activations, indicating that patients likely utilized the screened motor activity to achieve BCI control. Correlation values between topographies of the screening and control task were (patient 1: R=0.82, p<0.0001; patient 2: R=0.6108, p=0.0002; patient 3: R=0.7098, p<0.0001; patient 4: R=−0.0194; p=0.8994).

4. Discussion

This paper presents an important demonstration for the potential that hemispheric stroke survivors could use the unaffected side of their brain to potentially restore their unilateral motor deficit through the use of a BCI. By identifying cortical signals associated with ipsilateral hand movements, an EEG-based BCI can capture the brain’s intention to move a paretic hand. This can be accomplished irrespective of their actual capacity to execute a motor movement due to their injured primary motor cortex and/or descending white matter tracts. In this study, we demonstrate that it is possible to detect in EEG over the unaffected cortex, real and imagined intentions to move the stroke affected hand and, for the first time, show that these unaffected hemisphere signals can be used for simple brain-derived control of a device. Subjects achieved BCI control with peak accuracy rates between 62.5% and 100% rapidly, often with only a 30 minute screening task and less than 15 minutes of training. Importantly, these ipsilateral motor signals were distinct in anatomic location and spectral content from the cortical physiology associated with contralateral movements. This separable physiology and its ease of use for a BCI, provides an important first step towards using neuroprosthetic systems for a currently large and underserved patient population with motor disability. Given that stroke is the most common neurological disorder, affecting 795,000 patients per year in the U.S. alone (Lloyd-Jones, Adams et al. 2009), these findings can substantially extend the potential clinical impact of neuroprosthetic approaches.

This work was unique in its focus on using neural activity in the unaffected hemisphere related to intended movement of the ipsilateral limb for controlling a BCI system. While other studies have investigated the use of control signals from perilesional cortical areas (Buch, Weber et al. 2008; Daly, Cheng et al. 2009; Broetz, Braun et al. 2010), this is the first study to focus exclusively on ipsilateral motor activity from the unaffected hemisphere after stroke . This is important because BCI systems are likely to be most clinically relevant to stroke survivors with a chronic unrecovered hemiplegic motor deficit. Because stroke survivors with any residual motor functions are likely to be candidates for current rehabilitation methodologies (Takahashi, Der-Yeghiaian et al. 2008; Wolf, Thompson et al. 2010), BCI systems are likely to be used either by the most severely motor-impaired patients who had an absence of any function from the onset (limiting their rehabilitation options), or have failed to recover function after extensive therapy. Often these patient populations are likely to have significant cortical and/or subcortical lesions that transect the corticospinal tract descending to contralateral motor pathways (Binkofski, Seitz et al. 1996; Schaechter, Perdue et al. 2008; Carter, Patel et al. 2011). Because of these significant lesions, these patients are likely to have atypical neural activity in the affected hemisphere during intended movement of the contralateral limb when compared with normal controls (Calford and Tweedale 1990). By using ipsilateral motor intentions in the undamaged hemisphere for a BCI control signal, the impact of the stroke with regards to the quality of the control signal will be minimized. Taken together, there are likely two ways in which this methodology could be applied, either as a chronic BCI system for long-term assistive device control, or as BCI-assisted rehabilitation tool.

As in traditional BCI systems, stroke survivors could control an artificial device to aid in daily tasks or manipulate the hemiplegic limb. Building on work by Wisneski et al., who showed that motor intact patients could use ipsilateral motor signals for BCI control, this study extended those findings by demonstrating that stroke survivors can intentionally modulate similar ipsilateral motor signals from their unaffected hemisphere to control a BCI system. Several of the subjects that were studied in this study had fairly significant motor impairments from their strokes (Subjects 2, 3, and 4). Importantly, these subjects generally had shifts of the ipsilateral motor activity in their unaffected hemispheres to locations anterior to traditional sensorimotor cortices. This finding is in line with other results that have demonstrated changes in motor activity ipsilateral to the unaffected hemisphere (Cramer, Nelles et al. 1997; Green, Bialy et al. 1999; Tecchio, Zappasodi et al. 2006). It is important to note that the ipsilateral control signals were used to control a cursor on a screen as a proof of concept. This control could be easily extended to a simple one-dimensional grasping hand orthotic that could facilitate activities of daily living (Lauer, Peckham et al. 1999).

With regards to the choice of signal platform for utilizing an assistive BCI system after stroke, there are several considerations to take into account. In order to implement a traditional assistive BCI system, it will be important to scale the BCI control to a greater number of degrees of freedom. Currently, non-invasive BCI systems have produced at most 3 degrees-of-freedom in online task performance (McFarland, Sarnacki et al. 2010). This level of control required a large amount of training and utilized signals from both cortical hemispheres and midline electrodes that were related to movements of the feet and both hands. Given the broad cortical activations observed in EEG recordings, the necessity of developing BCI systems independent of the normal operation of the unaffected hand for completion of bimanual tasks, and attentional limitations to the amount of BCI training time in some patients, it is doubtful that EEG would allow for discernment of grasping and kinematic hand movements necessary for scaling an ipsilateral BCI system to a higher number of degrees of freedom in stroke survivors. Therefore, more complex control may require more invasive approaches such as electrocorticography (ECoG). To date, more complex movement kinematics of both hand and finger movements have been shown to be discernable using either macroscale or microscale ECoG signals (Wisneski, Anderson et al. 2008; Zanos, Miller et al. 2008; Leuthardt, Freudenberg et al. 2009; Scherer, Zanos et al. 2009). Additionally, ECoG has allowed for off-line decoding of 2D joystick movements from ipsilateral cortex (Ganguly, Secundo et al. 2009; Sharma, Gaona et al. 2009). As work continues to develop BCI systems for chronic stroke survivors, it will be important to gain a better understanding of the specific cortical dynamics associated with ipsilateral motor activity after stroke and the optimal signal platform that provides the highest benefit relative to the clinical risk of implementation.

In addition to providing a means for long-term assistive device control after stroke, BCI systems may provide a novel rehabilitation tool. The choice of motor signals from the unaffected hemisphere in this study has particular relevance to the potential for using BCI systems as a rehabilitation methodology. A number of previous studies have demonstrated changes in ipsilateral motor activity from the unaffected hemisphere after stroke. Functional imaging of chronic stroke survivors has shown increases in the ipsilateral motor activations of the unaffected hemisphere after recovery from stroke when compared to normal controls (Weiller, Chollet et al. 1992; Weiller, Ramsay et al. 1993; Cramer, Nelles et al. 1997; Nelles, Spiekramann et al. 1999; Tecchio, Zappasodi et al. 2006) as well as increases in ipsilateral, contralesional activity after constraint induced movement therapy (CIMT) (Levy, Nichols et al. 2001; Schaechter, Kraft et al. 2002). Furthermore, inhibitory transcranial magnetic stimulation in the unaffected premotor cortex slowed the reaction times for affected hand movements in stroke survivors (Johansen-Berg, Rushworth et al. 2002). While these results seem to indicate that ipsilateral activity from the unaffected hemisphere plays a facilitating role in recovery of motor function after stroke, there are also a number of studies that have shown potentially contradictory findings regarding increases in ipsilateral, contralesional motor activity after stroke. In particular, low ipsilateral TMS thresholds were associated with poor recovery after stroke (Turton, Wroe et al. 1996; Netz, Lammers et al. 1997) and decreases in ipsilateral activity from the unaffected hemisphere correlated with longitudinal and cross-sectional studies of recovery (Ward, Brown et al. 2003; Ward, Brown et al. 2003). It is important to note that several of the studies described above demonstrated both perilesional changes in activity, as well as ipsilateral activity from the unaffected hemisphere after recovery, indicating that both cortical areas may lead to recovery (Green, Bialy et al. 1999; Levy, Nichols et al. 2001). Furthermore, another study revealed that patients who recover completely showed few changes to the location of their contralesional motor activity, while patients that recovered incompletely showed better recovery with increased ipsilateral activity in the unaffected hemisphere (Tecchio, Zappasodi et al. 2006). This makes sense when one considers that corticospinal tract damage has been shown to be highly correlated with motor impairment after stroke (Fries, Danek et al. 1993; Carter, Patel et al. 2011). While patients with some residual motor function will most likely rehabilitate through reorganization of residual motor pathways, those for whom it is totally obliterated will likely need to develop new cortical and subcortical pathways (i.e. contralesional/ipsilateral motor pathways) for a more limited recovery. Thus, the patients that are most likely to be candidates for a BCI-based therapy, are those who have substantial damage to their corticospinal tract, requiring that an alternative pathway be utilized for functional rehabilitation to take place. Because of this, the results described in this paper demonstrating that stroke survivors can utilize ipsilateral motor activity from their unaffected hemisphere to control a BCI system represent a significant step in the development of a BCI system for encouraging rehabilitation after stroke. Moreover, in the setting of rehabilitation where the BCI is only needed transiently and the goal is to augment cortical plasticity, lower degrees of freedom for a less invasive option may be an ideal tradeoff in this clinical context.

While this work represents an exciting demonstration of the possibilities for stroke survivors to achieve increased function through controlling BCI systems with neural activity in their unaffected hemisphere, there are several limitations and future considerations. First, the work represents only a limited number of patients and while one patient (Patient 1), had some recovery, most of the patients were selected for participation because they had more significant motor impairments, making them more representative of the patient population most likely to benefit from BCI applications. Because of this it is unknown how well these results will generalize to the broader population of stroke survivors. However, the population included patients with lesions of both hemispheres as well as both cortical and subcortical infarcts (see Table 1), indicating that BCI systems can be utilized by patients with various lesion types and locations. Furthermore, because BCI systems will most likely be applied to the most significantly impaired patients, these subjects do represent the intended clinical population. Second, it is impossible to ensure that the subject’s BCI control is truly achieved through the screened motor imagery task, particularly in cases in which subjects have no visible motor control. In this study however, the similarity between neural activity during the screening and control tasks (see Figure 9) provide evidence that the subject is indeed performing the imagery task indicated. Additionally, a BCI system needs to function independently of the unaffected hand to allow for completion of bimanual tasks. Because of differences in the attentional requirements of attempting to move the unaffected hand, it is difficult to truly assess the independence of the ipsilateral, contralesional motor signals and the traditional contralateral, contralesional motor signals during bimanual tasks, however, the ability of two subjects (Patients 1 and 2) to achieve on-line control with alternating movements of the affected and unaffected hands provides evidence that ipsilateral, contralesional motor activity is independent from unaffected hand movement in this patient population. Finally, it is important to note that the observed increase in ipsilateral, contralesional activations after stroke may represent increases in the attentional requirements of attempting to move the affected hand (Johansen-Berg, Rushworth et al. 2002). Regardless of whether this represents increased attention as has been postulated from previous imaging literature or enhancements in motor planning, once this signal is identified and engaged by the user, its utilization becomes of importance to assistive technologies, or to functional reorganization of the cortex and its neural output for a novel purpose. In the future, it will be important to explicitly test the changes in neural activity in the unaffected hemisphere as stroke survivors use BCI systems for longer time periods.

In summary, these results move the applications of BCI forward to potentially benefit the large number of motor-impaired hemispheric stroke survivors. The study shows in particular that hemispheric stroke patients can volitionally control signals from the unaffected hemisphere for device operation. This specific use of the contralesional hemisphere may provide a novel neuroprosthetic approach for increasing function in the more impaired stroke populations whose rehabilitation options are currently limited.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number UL1 RR024992 and TL1 RR024995 from the NIH-National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and grant numbers 1R0100085606 and (NICHD) RO1 HD061117-05A2. We would also like to thank the patients who participated in this study. Without their interest and effort this research would not be possible.

Footnotes

Disclosures: ECL and DWM have stock ownership in the company Neurolutions

References

- Binkofski F, Seitz RJ, Arnold S, Classen J, Benecke R, Freund HJ. Thalamic metbolism and corticospinal tract integrity determine motor recovery in stroke. Ann Neurol. 1996;39(4):460–470. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broetz D, Braun C, Weber C, Soekadar SR, Caria A, Birbaumer N. Combination of brain-computer interface training and goal-directed physical therapy in chronic stroke: a case report. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24(7):674–679. doi: 10.1177/1545968310368683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch E, Weber C, Cohen LG, Braun C, Dimyan MA, Ard T, Mellinger J, Caria A, Soekadar S, Fourkas A, Birbaumer N. Think to move: a neuromagnetic brain-computer interface (BCI) system for chronic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39(3):910–917. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB, Tweedale R. Interhemispheric transfer of plasticity in the cerebral cortex. Science. 1990;249(4970):805–807. doi: 10.1126/science.2389146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AR, Astafiev SV, Lang CE, Connor LT, Rengachary J, Strube MJ, Pope DL, Shulman GL, Corbetta M. Resting interhemispheric functional magnetic resonance imaging connectivity predicts performance after stroke. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):365–375. doi: 10.1002/ana.21905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AR, Patel KR, Astafiev SV, Snyder AZ, Rengachary J, Strube MJ, Pope A, Shimony JS, Lang CE, Shulman GL, Corbetta M. Upstream Dysfunction of Somatomotor Functional Connectivity After Corticospinal Damage in Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1545968311411054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC, Finklestein SP, Schaechter JD, Bush G, Rosen BR. Activation of distinct motor cortex regions during ipsilateral and contralateral finger movements. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(1):383–387. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC, Mark A, Barquist K, Nhan H, Stegbauer KC, Price R, Bell K, Odderson IR, Esselman P, Maravilla KR. Motor cortex activation is preserved in patients with chronic hemiplegic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(5):607–616. doi: 10.1002/ana.10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC, Nelles G, Benson RR, Kaplan JD, Parker RA, Kwong KK, Kennedy DN, Finklestein SP, Rosen BR. A functional MRI study of subjects recovered from hemiparetic stroke. Stroke. 1997;28(12):2518–2527. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.12.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JJ, Cheng R, Rogers J, Litinas K, Hrovat K, Dohring M. Feasibility of a New Application of Noninvasive Brain Computer Interface (BCI): A Case Study of Training for Recovery of Volitional Motor Control After Stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2009;33(4):203–211. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e3181c1fc0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Matchar D, Divine GW, Feussner J. Measurement of motor recovery after stroke. Outcome assessment and sample size requirements. Stroke. 1992;23(8):1084–1089. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.8.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries W, Danek A, Scheidtmann K, Hamburger C. Motor recovery following capsular stroke. Role of descending pathways from multiple motor areas. Brain. 1993;116(Pt 2):369–382. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly K, Secundo L, Ranade G, Orsborn A, Chang EF, Dimitrov DF, Wallis JD, Barbaro NM, Knight RT, Carmena JM. Cortical representation of ipsilateral arm movements in monkey and man. J Neurosci. 2009;29(41):12948–12956. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2471-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JB, Bialy Y, Sora E, Ricamato A. High-resolution EEG in poststroke hemiparesis can identify ipsilateral generators during motor tasks. Stroke. 1999;30(12):2659–2665. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg LR, Serruya MD, Friehs GM, Mukand JA, Saleh M, Caplan AH, Branner A, Chen D, Penn RD, Donoghue JP. Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature. 2006;442(7099):164–171. doi: 10.1038/nature04970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Berg H, Rushworth MF, Bogdanovic MD, Kischka U, Wimalaratna S, Matthews PM. The role of ipsilateral premotor cortex in hand movement after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(22):14518–14523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222536799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Vive-Larsen J, Stoier M, Olsen TS. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part II: Time course of recovery. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(5):406–412. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubler A, Nijboer F, Mellinger J, Vaughan TM, Pawelzik H, Schalk G, McFarland DJ, Birbaumer N, Wolpaw JR. Patients with ALS can use sensorimotor rhythms to operate a brain-computer interface. Neurology. 2005;64(10):1775–1777. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158616.43002.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer RT, Peckham PH, Kilgore KL. EEG-based control of a hand grasp neuroprosthesis. Neuroreport. 1999;10(8):1767–1771. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199906030-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthardt EC, Freudenberg Z, Bundy D, Roland J. Microscale recording from human motor cortex: implications for minimally invasive electrocorticographic brain-computer interfaces. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27(1):E10. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthardt EC, Gaona C, Sharma M, Szrama N, Roland J, Freudenberg Z, Solis J, Breshears J, Schalk G. Using the electrocorticographic speech network to control a brain-computer interface in humans. J Neural Eng. 2011;8(3):036004. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/3/036004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthardt EC, Schalk G, Wolpaw JR, Ojemann JG, Moran DW. A brain-computer interface using electrocorticographic signals in humans. J Neural Eng. 2004;1(2):63–71. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/1/2/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy CE, Nichols DS, Schmalbrock PM, Keller P, Chakeres DW. Functional MRI evidence of cortical reorganization in upper-limb stroke hemiplegia treated with constraint-induced movement therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(1):4–12. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O’Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marple L. Digital spectral analysis with applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland DJ, Sarnacki WA, Wolpaw JR. Electroencephalographic (EEG) control of three-dimensional movement. J Neural Eng. 2010;7(3):036007. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/7/3/036007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelles G, Spiekramann G, Jueptner M, Leonhardt G, Muller S, Gerhard H, Diener HC. Evolution of functional reorganization in hemiplegic stroke: a serial positron emission tomographic activation study. Ann Neurol. 1999;46(6):901–909. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<901::aid-ana13>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netz J, Lammers T, Homberg V. Reorganization of motor output in the non-affected hemisphere after stroke. Brain. 1997;120(Pt 9):1579–1586. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.9.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfurtscheller G, Guger C, Muller G, Krausz G, Neuper C. Brain oscillations control hand orthosis in a tetraplegic. Neurosci Lett. 2000;292(3):211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse AG, Moran DW. Neural adaptation of epidural electrocorticographic (EECoG) signals during closed-loop brain computer interface (BCI) tasks. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009:5514–5517. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaechter JD, Kraft E, Hilliard TS, Dijkhuizen RM, Benner T, Finklestein SP, Rosen BR, Cramer SC. Motor recovery and cortical reorganization after constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke patients: a preliminary study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2002;16(4):326–338. doi: 10.1177/154596830201600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaechter JD, Perdue KL, Wang R. Structural damage to the corticospinal tract correlates with bilateral sensorimotor cortex reorganization in stroke patients. Neuroimage. 2008;39(3):1370–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SY, Haaland KY, Sainburg RL. Dissociation of initial trajectory and final position errors during visuomotor adaptation following unilateral stroke. Brain Res. 2009;1298:78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SY, Haaland KY, Sainburg RL. Hemispheric specialization and functional impact of ipsilesional deficits in movement coordination and accuracy. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(13):2953–2966. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk G, McFarland DJ, Hinterberger T, Birbaumer N, Wolpaw JR. BCI2000: a general-purpose brain-computer interface (BCI) system. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2004;51(6):1034–1043. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.827072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk G, Miller KJ, Anderson NR, Wilson JA, Smyth MD, Ojemann JG, Moran DW, Wolpaw JR, Leuthardt EC. Two-dimensional movement control using electrocorticographic signals in humans. J Neural Eng. 2008;5(1):75–84. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/5/1/008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer R, Zanos SP, Miller KJ, Rao RP, Ojemann JG. Classification of contralateral and ipsilateral finger movements for electrocorticographic brain-computer interfaces. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27(1):E12. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Gaona C, Roland J, Anderson N, Freudenberg Z, Leuthardt EC. Ipsilateral directional encoding of joystick movements in human cortex. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009:5502–5505. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5334559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi CD, Der-Yeghiaian L, Le V, Motiwala RR, Cramer SC. Robot-based hand motor therapy after stroke. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 2):425–437. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DM, Tillery SI, Schwartz AB. Direct cortical control of 3D neuroprosthetic devices. Science. 2002;296(5574):1829–1832. doi: 10.1126/science.1070291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecchio F, Zappasodi F, Tombini M, Oliviero A, Pasqualetti P, Vernieri F, Ercolani M, Pizzella V, Rossini PM. Brain plasticity in recovery from stroke: an MEG assessment. Neuroimage. 2006;32(3):1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turton A, Wroe S, Trepte N, Fraser C, Lemon RN. Contralateral and ipsilateral EMG responses to transcranial magnetic stimulation during recovery of arm and hand function after stroke. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;101(4):316–328. doi: 10.1016/0924-980x(96)95560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velliste M, Perel S, Spalding MC, Whitford AS, Schwartz AB. Cortical control of a prosthetic arm for self-feeding. Nature. 2008;453(7198):1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature06996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ, Frackowiak RS. Neural correlates of motor recovery after stroke: a longitudinal fMRI study. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 11):2476–2496. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NS, Brown MM, Thompson AJ, Frackowiak RS. Neural correlates of outcome after stroke: a cross-sectional fMRI study. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 6):14305–1448. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiller C, Chollet F, Friston KJ, Wise RJ, Frackowiak RS. Functional reorganization of the brain in recovery from striatocapsular infarction in man. Ann Neurol. 1992;31(5):463–472. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiller C, Ramsay SC, Wise RJ, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS. Individual patterns of functional reorganization in the human cerebral cortex after capsular infarction. Ann Neurol. 1993;33(2):181–189. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisneski KJ, Anderson N, Schalk G, Smyth M, Moran D, Leuthardt EC. Unique cortical physiology associated with ipsilateral hand movements and neuroprosthetic implications. Stroke. 2008;39(12):3351–3359. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.518175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SL, Thompson PA, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, Blanton SR, Nichols-Larsen DS, Morris DM, Uswatte G, Taub E, Light KE, Sawaki L. The EXCITE stroke trial: comparing early and delayed constraint-induced movement therapy. Stroke. 2010;41(10):2309–2315. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.588723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpaw JR, McFarland DJ. Control of a two-dimensional movement signal by a noninvasive brain-computer interface in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(51):17849–17854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403504101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanos S, Miller KJ, Ojemann JG. Electrocorticographic spectral changes associated with ipsilateral individual finger and whole hand movement. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:5939–5942. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4650569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]