Abstract

Some propose using phosphate binders in the CKD population given the association between higher levels of phosphorus and mortality, but their safety and efficacy in this population are not well understood. Here, we aimed to determine the effects of phosphate binders on parameters of mineral metabolism and vascular calcification among patients with moderate to advanced CKD. We randomly assigned 148 patients with estimated GFR=20–45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 to calcium acetate, lanthanum carbonate, sevelamer carbonate, or placebo. The primary endpoint was change in mean serum phosphorus from baseline to the average of months 3, 6, and 9. Serum phosphorus decreased from a baseline mean of 4.2 mg/dl in both active and placebo arms to 3.9 mg/dl with active therapy and 4.1 mg/dl with placebo (P=0.03). Phosphate binders, but not placebo, decreased mean 24-hour urine phosphorus by 22%. Median serum intact parathyroid hormone remained stable with active therapy and increased with placebo (P=0.002). Active therapy did not significantly affect plasma C-terminal fibroblast growth factor 23 levels. Active therapy did, however, significantly increase calcification of the coronary arteries and abdominal aorta (coronary: median increases of 18.1% versus 0.6%, P=0.05; abdominal aorta: median increases of 15.4% versus 3.4%, P=0.03). In conclusion, phosphate binders significantly lower serum and urinary phosphorus and attenuate progression of secondary hyperparathyroidism among patients with CKD who have normal or near-normal levels of serum phosphorus; however, they also promote the progression of vascular calcification. The safety and efficacy of phosphate binders in CKD remain uncertain.

CKD is a significant public health concern; roughly 13% of the US population has an estimated GFR (eGFR) below 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or albuminuria.1 The risks of death and cardiovascular disease in CKD are not fully explained by associated diabetes, hypertension, and other conventional risk factors.2 With declining kidney function, serum phosphorus concentration increases but generally remains within the normal range until late in stage 4 or 5 CKD. A normal or near-normal serum phosphorus concentration is maintained at the expense of elevated levels of the phosphaturic hormones parathyroid hormone (PTH) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23).3,4 Serum concentrations of phosphorus and hormones responsible for its regulation have been implicated as putative cardiovascular risk factors.5–9

Three intestinal phosphate binders are approved for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in patients with ESRD in the United States—calcium acetate (Phoslo; Fresenius), lanthanum carbonate (Fosrenol; Shire), and sevelamer carbonate (Renvela; Genzyme)—but none are approved for use in patients with CKD not on dialysis.10 Because higher serum phosphorus concentrations—even within the population reference range—are associated with mortality, some have proposed the use of phosphate binders to lower serum phosphorus in this population.11 We undertook this pilot clinical trial to determine the safety and efficacy of phosphate binders in patients with moderate CKD and normal or near-normal serum phosphorus concentrations.

Results

Enrollment, Baseline Characteristics, and Study Conduct

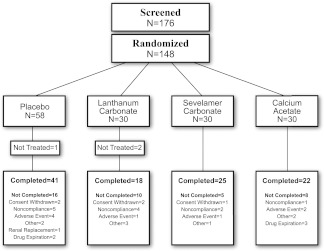

Figure 1 shows patient disposition. Baseline characteristics (Table 1) were similar across treatment groups. Mean doses of study medication were 5.9 g/d calcium acetate (1.5 g elemental calcium), 2.7 g/d lanthanum carbonate, and 6.3 g/d sevelamer carbonate. Average adherence was >85% in each of the treatment arms. The median duration of follow-up was 249 days. Changes in selected on-study biochemical parameters are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Table 2 shows adverse effects. Gastrointestinal side effects were more common with lanthanum but were generally mild and of limited duration. Only one related serious adverse event (hypothyroidism in placebo group) was observed during the study.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants

| All Active (n=88) | All Placebo (n=57) | Lanthanum (n=28) | Sevelamer (n=30) | Calcium (n=30) | Siga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| male | 50% | 49% | 54% | 50% | 47% | 1.00 |

| Caucasian | 81% | 79% | 82% | 80% | 80% | 1.00 |

| African-American | 10% | 11% | 7% | 7% | 17% | |

| age (years ± SD) | 68±11 | 65±12 | 70±10 | 66±12 | 68±12 | 0.72 |

| body mass index (kg/m2 ± SD) | 31±9 | 32±8 | 30±7 | 33±8 | 30±5 | 0.08 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| diabetes | 56% | 58% | 57% | 53% | 57% | 0.86 |

| CHF | 27% | 11% | 25% | 23% | 33% | 0.02 |

| CAD | 26% | 14% | 21% | 27% | 30% | 0.10 |

| HTN | 98% | 100% | 100% | 97% | 97% | 0.52 |

| MI | 12% | 5% | 4% | 23% | 10% | 0.25 |

| PVD | 24% | 19% | 21% | 20% | 30% | 0.55 |

| CVA | 8% | 4% | 14% | 3% | 7% | 0.48 |

| secondary hyperparathyroidism | 72% | 72% | 79% | 60% | 77% | 1.00 |

| hyperlipidemia | 89% | 93% | 86% | 97% | 83% | 0.57 |

| nontraumatic fracture | 17% | 18% | 7% | 23% | 20% | 1.00 |

| Laboratory characteristics | ||||||

| serum phosphorus (mg/dl ± SD)b | 4.2±0.4 | 4.2±0.4 | 4.2±0.4 | 4.2±0.4 | 4.2±0.4 | 0.47 |

| eGFR (ml/min ± SD)b | 32±8.1 | 30±8.5 | 33±7.9 | 32±9.1 | 30±7.1 | 0.32 |

| intact PTH (pg/ml ± SD)c | 78±56 | 91±52 | 87±54 | 70±56 | 76±58 | 0.05 |

| C-terminal FGF23 (RU/ml ± IQR)c | 227 (135–322) | 211 (140–278) | 230 (126–368) | 230 (143–362) | 219 (157–287) | 0.59 |

| intact FGF23 (pg/mL ± IQR)c | 120 (88–176) | 119 (95–169) | 111 (65–194) | 147 (95–202) | 114 (90–152) | 0.79 |

| 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin Db | 25.7±9.4 | 27.2±10.3 | 26.9±10.0 | 24.7±10.3 | 25.5±8.1 | 0.69 |

| coronary artery calcium volume scorec | 262 (87–863) | 225 (18–737) | 216.5 (102–1694) | 362.5 (113–940.5) | 130 (13–645) | 0.33 |

| thoracic aorta calcium volume scorec | 583 (165–2282) | 496 (58–1539) | 1609 (98–5030) | 536 (351–2147) | 511 (50–2145) | 0.52 |

| abdominal aorta calcium volume scorec | 1551 (326–5377) | 1693 (212–6861) | 4035 (200–8578) | 1367 (519–3234) | 1468 (16–4328) | 0.70 |

| L2 to L4 bone mineral density (g/cm2)b | 111±34 | 108±45 | 99±22 | 111±29 | 120±42 | 0.45 |

| total urinary excretion of phosphorus (mg ± SD)b,d | 757±444 | 805±359 | 747±606 | 769±350 | 727±354 | 0.20 |

| fractional excretion of phosphorus (% ± SD)b | 0.32±0.12 | 0.31±0.10 | 0.30±0.13 | 0.33±0.12 | 0.33±0.11 | 0.48 |

| total urinary excretion of calcium (mg ± SD)b,d | 55±42 | 61±47 | 53±40 | 56±43 | 58±43 | 0.69 |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebro-vascular disease; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; PVD, peripheral vascular disease.

Significance. Fisher exact test for all active versus all placebo for binary measures and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous measures.

Mean.

Median (IQR).

Twenty-four hour urine measurements were adjusted for adequacy of collection using the mean of each individual urinary creatinine excretion.

Table 2.

Related adverse events on study

| Related Adverse Event | All Active (n=88) | All Placebo (n=57) | Lanthanum (n=28) | Sevelamer (n=30) | Calcium (n=30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One or more adverse events (n; %) | 31 | 12 | 8 (29) | 10 (33) | 13 (43) |

| Constipation (n; %) | 11 | 0 | 2 (7) | 5 (17) | 4 (13) |

| Diarrhea (n; %) | 5 | 1 | 5 (18) | ||

| Dyspepsia (n; %) | 4 | 1 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (7) |

| Hypercalcemia (n; %) | 5 | 0 | 5 (17) | ||

| Vomiting (n; %) | 4 | 1 | 4 (14) | ||

| Flatulence (n; %) | 2 | 2 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| Nausea (n; %) | 3 | 1 | 3 (11) | ||

| Hypophosphatemia (n; %) | 2 | 1 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| Abdominal pain (n; %) | 0 | 2 | |||

| Acidosis (n; %) | 2 | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| Myalgia (n; %) | 1 | 1 | 1 (3) | ||

| AKI (n; %) | 1 | 0 | 1 (3) | ||

| Dysgeusia (n; %) | 0 | 1 | |||

| GERD (n; %) | 1 | 0 | 1 (3) | ||

| Hyperparathyroidism (n; %) | 0 | 1 | |||

| Hypothyroidism (n; %) | 0 | 1 |

Fisher exact test for all active versus all placebo. GERD, gastro-esophageal reflux disease.

Primary Endpoint

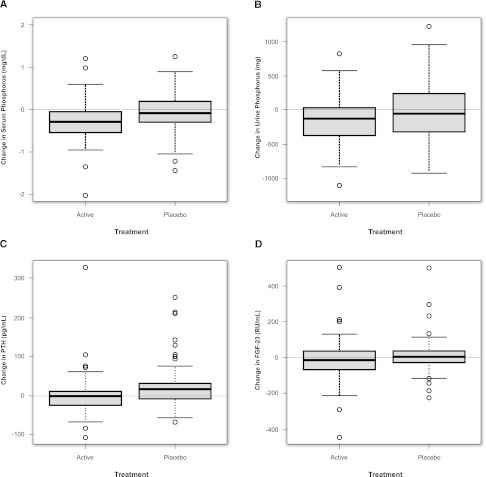

Change in mean serum phosphorus was significantly different between active- and placebo-treated groups (P=0.03). Mean serum phosphorus declined from 4.2 to 3.9 mg/dl in patients treated with phosphate binders and was unchanged in placebo-treated patients (Figure 2A). Results in the individual active treatment arms show statistically significant reductions versus placebo only in the lanthanum carbonate arm (P=0.04), and they are shown in Supplemental Figure 1A.

Figure 2.

Biochemical changes on study by treatment arm. Change in (A) median (interquartile range [IQR]) serum phosphorus, (B) 24-hour urine phosphorus, (C) PTH, and (D) C-terminal FGF23 over the study period among all active- and placebo-treated patients.

Secondary Endpoints

Urine Phosphorus

Change in mean urine phosphorus excretion was significantly different between active- and placebo-treated groups (P=0.002) (Figure 2B). Daily urine phosphorus excretion was reduced by 22% with active therapy and unchanged with placebo. Similar results were observed for the mean fractional excretion of phosphorus, which decreased (32%–26%) with active treatment and was unchanged (31%–32%) with placebo (P<0.0001). All active treatment arms showed similar reductions in phosphorus excretion (Supplemental Figure 1B).

PTH and 1,25 Dihydroxy Vitamin D

Change in PTH was significantly different between active- and placebo-treated groups (P=0.002). PTH concentrations remained stable with active therapy and increased by 21% in patients on placebo (P=0.002) (Figure 2C). 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D concentration was significantly reduced with active therapy (P=0.004) (Supplemental Table 1). Effects on PTH and 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D seemed to differ by binder type; patients treated with calcium acetate experienced a larger relative decline, whereas the effects of lanthanum and sevelamer relative to placebo were less pronounced (Supplemental Figure 1C and Supplemental Table 1).

FGF23

Plasma C-terminal FGF23 concentrations were markedly elevated in both treatment arms at baseline relative to population norms. There was no significant difference in the change between active and placebo in plasma C-terminal FGF23 (P=0.67) (Figure 2D). Findings using the intact FGF23 assay measured at baseline and end of study similarly showed no difference between all active and all placebo (P=0.42). The effects on intact FGF23 seemed to differ by binder type; patients treated with sevelamer carbonate experienced a significant decrease in intact FGF23 (median decrease=24 pg/ml, P=0.002 versus placebo), whereas those patients treated with calcium acetate had a significant increase (median increase=28 pg/ml, P=0.03 versus placebo) and those patients treated with lanthanum carbonate were no different compared with placebo (P=0.30) (Supplemental Figure 2, D and E).

Vascular Calcification and Bone Mineral Density

Assessment of change in vascular calcification was available in a subset of 96 patients (60 active and 36 placebo). No patient with a zero calcium score at baseline developed a positive score during follow-up. Among patients with nonzero calcium scores at baseline (n=81), active therapy resulted in significant increases in median annualized percent change of coronary artery (P=0.05) (Figure 3A) and abdominal aorta (P=0.03) (Figure 3B) calcium volume scores. Using the Hokanson square-root follow-up criterion, 20 of 52 (38%) phosphate binder-treated patients experienced progression of coronary artery calcification compared with 5 of 29 (17%) placebo-treated patients (P=0.03). There was no significant difference in the thoracic aorta calcium score by treatment status (Figure 3C). Phosphate binder-treated patients showed significant improvement (P=0.03) in annualized change in bone mineral density (BMD) (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Vascular calcification and bone mineral density changes on study by treatment arm. Percent change in (A) median (IQR) annualized total coronary artery, (B) abdominal aorta, and (C) thoracic aorta calcium volume scores among active- and placebo-treated patients. (D) Median (IQR) percent change in annualized BMD among active- and placebo-treated patients. A trained reader examined each region of interest with exclusion of vertebral abnormalities.

The apparent adverse effects on vascular calcification and salutary effects on BMD were most pronounced among patients randomized to calcium acetate (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Discussion

This randomized placebo-controlled pilot clinical trial shows that the use of phosphate binders in patients with nondialysis-requiring CKD reduces urinary phosphorus excretion (a surrogate of intestinal phosphate absorption) and attenuates progressive secondary hyperparathyroidism. The effect on serum phosphorus, although statistically significant, was modest, despite relatively high-dose therapy and a significant effect on urinary phosphorus excretion. Active therapy resulted in progression of vascular calcification, particularly among patients randomized to calcium acetate.

Higher serum phosphorus concentrations within the normal range are associated with cardiovascular events and mortality in persons with CKD as well as persons with normal or near-normal kidney function.12–14 For example, among 3368 participants in the Framingham Offspring Study who were free of cardiovascular or kidney disease followed for 16.1 years, a serum phosphorus>3.5 mg/dl was associated with a 55% higher risk for a first cardiovascular event.12 In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (n=15,732), the corresponding multivariable-adjusted relative risk of death was increased by 14% (P<0.001).15 More recently, a reanalysis of the Ramipril in Nondiabetic Renal Disease study showed that patients with serum phosphorus>3.5 mg/dl were more than two times as likely to experience progression to ESRD or a doubling of serum creatinine. Moreover, higher serum phosphorus attenuated the renoprotective benefit of ramipril.16

The lack of a larger change in measured serum phosphorus is surprising given the relatively large reduction in urine phosphorus excretion, although similar findings have been reported in the work by Oliveira et al.17 A single determination of serum phosphorus may not accurately reflect the time-averaged value. In normal, healthy men given phosphorus-supplemented diets, single, fasting morning serum phosphorus concentrations grossly underestimate 24-hour exposure to phosphorus and fail to distinguish between low and high dietary phosphorus intake.18 Our results suggest that, in moderate to advanced CKD, the serum phosphorus concentration may be a relatively poor marker of phosphate binder efficacy or adherence.

Intestinal absorption of phosphate is highly dependent on the nature and absolute amount of ingested phosphorus and the expression of the intestinal sodium–phosphorus cotransporter type 2b (NPT2b). Heterozygous NPT2b knockout mice show a 50% reduction in receptor expression but have identical serum phosphorus concentrations compared with wild-type mice.19 Mice with an inducible conditional knockout of NPT2b also maintain serum phosphate concentrations, possibly the result of compensatory increases in paracellular intestinal phosphate absorption and renal expression of NPT2a and NPT2c.4,20 If phosphate binders were to upregulate expression of intestinal NPT2b and enhance paracellular transport, the efficacy of binders could be limited, particularly after missed doses. Clinical trials of niacin and niacin derivatives, which are known to inhibit the expression of intestinal NPT2b and kidney NPT2a, have shown significant reductions in serum phosphorus in patients with mild to moderate CKD.21

FGF23 seems to be a sensitive marker of impaired kidney function, with elevations preceding detectable increases in serum creatinine.22 Circulating FGF23 concentrations are strongly associated with progression to ESRD and mortality, and higher concentrations of FGF23 have recently been shown to cause left ventricular hypertrophy in rats.9 It had been assumed that reduction in intestinal phosphate absorption would decrease FGF23, although shorter-term phosphate binder intervention failed to show any reduction in FGF23, despite yielding significant reductions in urinary phosphorus excretion.23 Whether our disparate findings with C-terminal and intact FGF23 reflect better precision with the intact assay or true differential effects on both molecules is unknown. A similarly discrepant result between the C-terminal and intact FGF23 assays was described in 66 subjects with normal kidney function, in whom dietary phosphate restriction reduced intact FGF23 but had no effect on C-terminal FGF2.24 Our results confirm the results in the works by Olivieri et al.17 and Yilmaz et al.25 Despite what seems to represent similar efficacy in terms of intestinal phosphate binding, intestinal phosphate binders seem to exert disparate effects on serum concentrations of FGF23.17,25 Treatment with phosphate binders resulted in significant progression of vascular calcification in coronary arteries and the abdominal aorta. Assessment of coronary artery calcification (CAC) progression using the square-root follow-up method in the work by Hokanson et al.26 has been shown to be the best method to predict mortality in a large cohort of asymptomatic patients.26,27 These results support the conceptual risk of inducing positive calcium balance in patients with CKD, where disordered mineral metabolism results in dystrophic calcification. Short-term calcium balance studies suggest that the provision of 2000 mg/d elemental calcium in patients with CKD stage 3 results in substantial net positive calcium balance.28 However, progression of vascular calcification was evident not only in patients receiving calcium acetate, suggesting that use of other phosphate binders in CKD might also have unexpected and potentially, adverse consequences. It is possible that noncalcium-containing phosphate binders also enhance the availability of free intestinal calcium and result in a positive calcium balance. Although our primary analyses compared all actively treated groups with placebo, subgroup analyses suggested that calcium- and noncalcium-containing phosphate binders exert differential effects on PTH, FGF23, and mineralization of the bone and vasculature. In contrast, the work by Russo et al.29 studied 2-year progression of calcification in 90 patients with CKD stage 3/4 randomized to a low phosphate diet, sevelamer carbonate, or calcium carbonate. Patients receiving calcium carbonate experienced marked progression of CAC; however, in their analysis, subjects given a low phosphate diet alone had rates of CAC progression similar those subjects receiving calcium, whereas our placebo-treated subjects experienced little or no progression in CAC.

This study has several strengths, including the relatively long study duration, blinding of participants and investigators, and excellent overall adherence. This study also has several important limitations. This study was a single-center study, which served to diminish any impact of regional or cultural differences of diet on serum phosphorus concentrations but may have limited the generalizability of our findings to other geographic regions. We may have observed larger or less variable effects of phosphate binder therapy on serum phosphorus had we standardized the time of day at which serum phosphorus was measured. We made no attempts to standardize intake of phosphorus, calcium, or other dietary components, and we made no attempt to standardize sun exposure or limit or match enrollment by season.

In summary, treatment with phosphate binders in patients with moderate to advanced CKD and normal or near-normal serum phosphorus concentrations significantly lowered serum and urinary phosphorus and attenuated progression of secondary hyperparathyroidism, but it resulted in progression of coronary artery and abdominal aortic calcification. The safety and efficacy of phosphate binders in patients with CKD and normal serum phosphorus remain uncertain.

Concise Methods

Study Setting

This trial was a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of phosphate binders in patients with moderate to advanced CKD. Recruitment at a single study center (Denver Nephrologists, Denver, CO) began in February of 2009 and continued until September of 2010. Active drug and matching placebo were supplied by the three manufacturers. The protocol was developed by an independent steering committee with full authority over study design and conduct. A four-member independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed safety data. The study was approved by the Schulman Institutional Review Board (Cincinnati, OH) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT 00785629).

Study Population

We obtained written informed consent from all patients. Patients were identified using an electronic medical record to capture all consecutive patients seen in the study center clinic offices who met preliminary study criteria. Patients were required to have an eGFR using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation between 20 and 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, a serum phosphorus≥3.5 and <6.0 mg/dl, and willingness to avoid any intentional change in diet. Key exclusion criteria included use of any medication for the purpose of binding intestinal phosphate, use of any active vitamin D or the calcimimetic cinacalcet, intact PTH≥500 pg/ml, or uncontrolled hyperlipidemia.

Study Design

An independent statistician performed randomization using SAS version 9.1. A random seed was set, and data were generated using a Data Step with a sequence of uniform random deviates. Patients were block-randomized into one of three treatment arms, calcium acetate, lanthanum carbonate, and sevelamer carbonate, in a 1:1:1 fashion. We then randomly assigned patients within each treatment arm to receive either active medication or matching placebo (3:2). Statistical comparisons were made between the two treatment groups—all active versus all placebo. We stratified randomization by diabetic status. Sealed envelopes were opened at the study center by a staff member not involved in the conduct of the trial. All study medication was released by a single unblinded staff member in bottles identified by a unique identification number. All clinical personnel, data analysts, and participants remained blinded to study treatment assignment. We administered 1 or 2 units per meal of study medication (calcium acetate=667 mg, lanthanum carbonate=500 mg, and sevelamer carbonate=800 mg) based on screening serum phosphorus below or above 4.5 mg/dl. We increased study medication at each visit if the serum phosphorus remained >3.5 mg/dl to a maximum dose of 4 calcium acetate per meal (2668 mg), 3 lanthanum carbonate per meal (1500 mg), or 4 sevelamer carbonate per meal (3200 mg). We gave all patients cholecalciferol (1000 IU daily). Patients underwent laboratory testing and event assessment at week 2 and months 1, 2, 3, 6, and 9. We assessed adherence with pill counts at each study visit.

Study Assessments

Laboratory Assessments

All clinical chemistry analyses were performed by Quest Diagnostics (Denver, CO). We obtained samples in a nonfasting state but generally at the same time of day. Timed and spot urine chemistry measurements were performed by Litholink Corp. (Chicago, IL). Protein intake was estimated using the equation 6.25×(urine urea nitrogen in grams+30 mg/kg)+1 g/g proteinuria>5 g.29 Phosphorus intake was estimated using the equation 11.8×protein intake in grams+78.30

1,25 Dihydroxy vitamin D assays were performed using a commercially available radioimmunosassay (Diasorin Inc., Stillwater, MN). We measured FGF23 in plasma using the second generation C-terminal ELISA assay (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA); we also measured intact FGF23 at baseline and month 9 using a sandwich immunoassay (Kainos, Japan).

Imaging Assessments

We used the GE-Imatron C150 scanner at baseline and month 9 using a standard protocol as previously described.31 We defined atherosclerotic calcium as a plaque area≥1 mm2 with a density of ≥130 Hounsfield units. Total calcium volume score was derived by the sum of all lesion volumes in cubic millimeters.32 The thoracic aorta was defined as the segment from the aortic root to the diaphragm, whereas the abdominal aorta was the segment from the diaphragm to the iliac bifurcation. A single experienced investigator, blinded to treatment assignment, performed all image assessments.

Lumbar BMD was determined using abdominal computed tomography scans with a calibrated phantom of known density (Image Analysis QCT 3D PLUS, Columbia, KY). Measurements of BMD were performed in a 5-mm-thick slice of trabecular bone from each vertebra (L2 to L4) at baseline and month 9.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was change in serum phosphorus from baseline (the average of the last two measures in screening) to the mean of months 3, 6, and 9 among all active- versus all placebo-treated patients. Secondary laboratory endpoints included changes in serum PTH, FGF23, 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D, urine phosphorus, and fractional excretion of phosphorus. Secondary clinical endpoints included change in coronary artery, thoracic and abdominal aorta calcium volume scores, and change in lumbar BMD. Comparisons of individual treatment arms versus placebo were considered exploratory.

Sample Size Determination

We estimated that a sample size of 150 (90 active versus 60 placebo) would provide >80% power to detect a change in serum phosphorus≥0.4 mg/dl between groups, with a two-sided α=0.05 and an anticipated dropout rate of 25%.

Statistical Analyses

We analyzed all data in accordance with the intent-to-treat principle comparing all actively treated patients with all placebo-treated patients. We imputed missing data using last observation carried forward. We used analysis of covariance to examine change in endpoints incorporating age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetes, eGFR, and baseline values as covariates. Because of the association of race with PTH concentration, race/ethnicity was self-reported by subjects from a prespecified list including Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic or Latino, Asian, and American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or Other. We used a Dunnett correction when comparing individual active arms with placebo. For the analysis of change in calcification, we included only patients with nonzero calcification at baseline. In companion analyses, we used the Hokanson criterion to gauge progression of vascular calcification.26 For the analysis of change in BMD, we additionally considered Quetélet’s (body mass) index and history of nontraumatic fracture as covariates. We performed statistical analyses using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Disclosures

G.A.B. has received research grants from Amgen, Roche, Cytochroma, and CMD; received honoraria from Genzyme; has been on advisory boards or a consultant for Amgen, Genzyme, KAI, Ardelyx, and Mitsubishi; and was a Medical Director for Davita. D.C.W. received research grants from Genzyme and Abbott and honoraria from Amgen, Fresenius, and Shire; and has been on the advisory board for KAI. M.S.P. has consulted for KAI. B.K. has received a research grant from Amgen. M.K. has received research grants from Amgen and Abbott; honoraria from Amgen, Abbott, Genzyme, FMC, Medice, and Shire; and payment for development of educational presentations from Amgen and Abbott; and has been a consultant for Amgen, Abbott, Genzyme, FMC, Medice, and Shire. D.M.S. has received research grants from Amgen and Keryx and honoraria from Amgen and Sanofi; has been on advisory boards for Affymax, Amgen, and Sanofi; and has been a consultant for Amgen. J.A. has been an employee of LabCorp and a consultant for Oxthera Corp. .N.H. has received research grants from Waters and has been a consultant for Onconome. R.T. has received a research grant from Abbott; has been a consultant for Fresenius North America and Mitsubishi Tanabe; and has received honoraria from Shire. M.W. has received research grants from National Institutes of Health, Shire, Amgen, and Genzyme; has received honoraria from Abbott, Genzyme, and Shire; and has been a consultant for Abbott, Genzyme, Luitpold, Mitsubishi, Cytochroma, Biotrends, Ardelyx, and Astellas. G.M.C. has received a research grant from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Amgen, and Reata; and has been an advisor for Ardelyx. M.A.A., G.S., L.K., and M.M. have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Stephanie Brillhart, MSCI, and Linda Loftin, NP, for their assistance in the conduct of the trial as the designated unblinded study representatives for study drug storage and assignment. The authors would also like to acknowledge the important contribution of our Data Safety and Monitoring Committee, led by the Chairman, Colin Baigent, FRCP. Members of this committee donated their time and expertise in providing oversight of the trial conduct. In addition to Dr. Baigent, committee members included Grahame Elder, Alistair Hutchison, FRCP, Jonathan Emberson, PhD, and Edmung Ng.

G.A.B., D.C.W., M.S.P., B.K., M.K., D.M.S., J.A., R.T., M.W., and G.M.C. participated in the design, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. G.S., M.A.A., A.N.H., and M.M. participated in data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. L.K. participated in the design and data acquisition. G.A.B. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding for this investigator-initiated study was provided by Shire, Inc., Fresenius NA, Genzyme, Inc., Denver Nephrologists, PC, Novartis, Inc., and Davita, Inc.

Funding entities had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript. Each funding entity was permitted to review the manuscript for verification that no proprietary or confidential information was included.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Phosphate Binders in CKD: Bad News or Good News?,” on pages 1277–1280.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012030223/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System : USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa H, Nagano N, Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Iijima K, Fujita T, Yamashita T, Fukumoto S, Shimada T: Direct evidence for a causative role of FGF23 in the abnormal renal phosphate handling and vitamin D metabolism in rats with early-stage chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 78: 975–980, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stubbs JR, He N, Idiculla A, Gillihan R, Liu S, David V, Hong Y, Quarles LD: Longitudinal evaluation of FGF23 changes and mineral metabolism abnormalities in a mouse model of chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res , 2011 10.1002/jbmr.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, Xie D, Anderson AH, Scialla J, Wahl P, Gutiérrez OM, Steigerwalt S, He J, Schwartz S, Lo J, Ojo A, Sondheimer J, Hsu CY, Lash J, Leonard M, Kusek JW, Feldman HI, Wolf M, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group : Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA 305: 2432–2439, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng M, Wolf M, Ofsthun MN, Lazarus JM, Hernán MA, Camargo CA, Jr, Thadhani R: Activated injectable vitamin D and hemodialysis survival: A historical cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1115–1125, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danese MD, Belozeroff V, Smirnakis K, Rothman KJ: Consistent control of mineral and bone disorder in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1423–1429, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chue CD, Edwards NC, Williams ME, Steeds RP, Townend JN, Ferro CJ: Serum phosphate is associated with left ventricular mass in patients with chronic kidney disease: A cardiac magnetic resonance study. Heart 98: 219–224, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, Hu MC, Sloan A, Isakova T, Gutiérrez OM, Aguillon-Prada R, Lincoln J, Hare JM, Mundel P, Morales A, Scialla J, Fischer M, Soliman EZ, Chen J, Go AS, Rosas SE, Nessel L, Townsend RR, Feldman HI, St John Sutton M, Ojo A, Gadegbeku C, Di Marco GS, Reuter S, Kentrup D, Tiemann K, Brand M, Hill JA, Moe OW, Kuro-O M, Kusek JW, Keane MG, Wolf M: FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 121: 4393–4408, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovesdy CP, Kuchmak O, Lu JL, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Outcomes associated with phosphorus binders in men with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 842–851, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42[Suppl 3]: S1–S201, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhingra R, Sullivan LM, Fox CS, Wang TJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Gaziano JM, Vasan RS: Relations of serum phosphorus and calcium levels to the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the community. Arch Intern Med 167: 879–885, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, Patterson DJ, Seliger SL, Young B, Sherrard DJ, Andress DL: Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 520–528, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Gao Z, Curhan G, Cholesterol And Recurrent Events Trial Investigators : Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation 112: 2627–2633, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foley RN, Collins AJ, Ishani A, Kalra PA: Calcium-phosphate levels and cardiovascular disease in community-dwelling adults: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J 156: 556–563, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zoccali C, Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Leonardis D, Tripepi R, Tripepi G, Mallamaci F, Remuzzi G, REIN Study Group : Phosphate may promote CKD progression and attenuate renoprotective effect of ACE inhibition. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1923–1930, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira RB, Cancela AL, Graciolli FG, Dos Reis LM, Draibe SA, Cuppari L, Carvalho AB, Jorgetti V, Canziani ME, Moysés RM: Early control of PTH and FGF23 in normophosphatemic CKD patients: A new target in CKD-MBD therapy? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 286–291, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Portale AA, Halloran BP, Morris RC, Jr: Dietary intake of phosphorus modulates the circadian rhythm in serum concentration of phosphorus. Implications for the renal production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J Clin Invest 80: 1147–1154, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohi A, Hanabusa E, Ueda O, Segawa H, Horiba N, Kaneko I, Kuwahara S, Mukai T, Sasaki S, Tominaga R, Furutani J, Aranami F, Ohtomo S, Oikawa Y, Kawase Y, Wada NA, Tachibe T, Kakefuda M, Tateishi H, Matsumoto K, Tatsumi S, Kido S, Fukushima N, Jishage K, Miyamoto K: Inorganic phosphate homeostasis in sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter Npt2b⁺/⁻ mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F1105–F1113, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabbagh Y, O’Brien SP, Song W, Boulanger JH, Stockmann A, Arbeeny C, Schiavi SC: Intestinal npt2b plays a major role in phosphate absorption and homeostasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2348–2358, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ix JH, Ganjoo P, Tipping D, Tershakovec AM, Bostom AG: Sustained hypophosphatemic effect of once-daily niacin/laropiprant in dyslipidemic CKD stage 3 patients. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 963–965, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutiérrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, Appleby D, Nessel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Hamm L, Gadegbeku C, Horwitz E, Townsend RR, Anderson CA, Lash JP, Hsu CY, Leonard MB, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 79: 1370–1378, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isakova T, Gutierrez OM, Smith K, Epstein M, Keating LK, Jappner H, Wolf M: Pilot study of dietary phosphorus restriction and phosphorus binders to target fibroblast growth factor 23 in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 584–591, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burnett SM, Gunawardene SC, Bringhurst FR, Jüppner H, Lee H, Finkelstein JS: Regulation of C-terminal and intact FGF-23 by dietary phosphate in men and women. J Bone Miner Res 21: 1187–1196, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yilmaz MI, Sonmez A, Saglam M, Yaman H, Kilic S, Eyileten T, Caglar K, Oguz Y, Vural A, Yenicesu M, Mallamaci F, Zoccali C: Comparison of calcium acetate and sevelamer on vascular function and fibroblast growth factor 23 in CKD patients: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 177–185, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hokanson JE, MacKenzie T, Kinney G, Snell-Bergeon JK, Dabelea D, Ehrlich J, Eckel RH, Rewers M: Evaluating changes in coronary artery calcium: An analytic method that accounts for interscan variability. AJR Am J Roentgenol 182: 1327–1332, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budoff M, Hokanson JE, Nasir K, Shaw LJ, Kinney GL, Chow D, Demoss DNuguri V, Nabavi V, Ratakonda R, Berman DS, Raggi P: Progression of coronary artery calcium predicts all-cause mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 3: 1229–1236, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel DM, Brady K: Calcium balance in normal individuals and in patients with chronic kidney disease on low- and high-calcium intake. Kidney Int 81: 1116–1122, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russo D, Miranda I, Ruocco C, Battaglia Y, Buonanno E, Manzi S, Russo L, Scafarto A, Andreucci YE: The progression of coronary artery calcification in pre-dialysis patients on calcium carbonate or sevelamer. Kidney Int 72: 1255–1261, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Gutekunst L, Mehrotra R, Kovesdy CP, Bross R, Shinaberger CS, Noori N, Hirschberg R, Benner D, Nissenson AR, Kopple JD: Understanding sources of dietary phosphorus in the treatment of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 519–530, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegel DM, Raggi P, Mehta R, Lindberg JS, Chonchol M, Ehrlich J, James G, Chertow GM, Block GA: Coronary and aortic calcifications in patients new to dialysis. Hemodial Int 8: 265–272, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Callister TQ, Raggi P, Cooil B, Lippolis NJ, Russo DJ: Effect of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on coronary artery disease as assessed by electron-beam computed tomography. N Engl J Med 339: 1972–1978, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]