Abstract

Marijuana abuse during adolescence may alter its abuse liability during adulthood by modifying the interoceptive (discriminative) stimuli produced, especially in females due to an interaction with ovarian hormones. To examine this possibility, either gonadally intact or ovariectomized (OVX) female rats received 40 intraperitoneal injections of saline or 5.6 mg/kg of Δ9-THC daily during adolescence, yielding 4 experimental groups (intact/saline, intact/Δ9-THC, OVX/saline, and OVX/Δ9-THC). These groups were then trained to discriminate Δ9-THC (0.32–3.2 mg/kg) from saline under a fixed-ratio (FR) 20 schedule of food presentation. After a training dose was established for the subjects in each group, varying doses of Δ9-THC were substituted for the training dose to obtain dose-effect (generalization) curves for drug-lever responding and response rate. The results showed that: 1) the OVX/saline group had a substantially higher mean response rate under control conditions than the other three groups, 2) both OVX groups had higher percentages of THC-lever responding than the intact groups at doses of Δ9-THC lower than the training dose, and 3) the OVX/Δ9-THC group was significantly less sensitive to the rate-decreasing effects of Δ9-THC compared to other groups. Furthermore, at sacrifice, western blot analyses indicated that chronic Δ9-THC in OVX and intact females decreased cannabinoid type-1 receptor (CB1R) levels in striatum, and decreased phosphorylation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein (p-CREB) in intact and OVX females in hippocampus. In contrast to hippocampus, chronic Δ9-THC only decreased p-CREB in the OVX group in striatum. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) was not significantly affected by either hormone status or chronic Δ9-THC. In summary, these data in female rats suggest that cannabinoid abuse by adolescent human females could alter their subsequent responsiveness to cannabinoids as adults and have serious consequences for brain development.

1. Introduction

Experience with the effects of marijuana during adolescence might contribute to its abuse in adults by permanently altering the perception or composition of the interoceptive stimuli produced, as these stimuli comprise the subjective experience induced by this drug. Furthermore, as stated by Holtzman (1990), “the qualitative nature of the subjective effects that a drug produces is a principal determinant of the abuse potential of that drug,” p. 193. One experimental method for investigating the subjective effects of a drug is to have a specific dose of that drug serve as discriminative stimuli for responding in a discrimination procedure (Balster and Prescott, 1992; Jarbe et al., 1989). A powerful aspect of this methodology is that once the subjective effects of a drug are conditioned to serve reliably as discriminative stimuli, the experimenter has a pharmacologically-specific behavioral model for studying the components of a drug’s actions, which generally reflect events at the neuronal level (Balster and Prescott, 1992; Holtzman, 1990).

To test the hypothesis that the discriminative stimulus effects may differ substantially between Δ9-THC-experienced and Δ9-THC-naïve individuals, we established Δ9-THC as a discriminative stimulus in adult female rats that had received it chronically as adolescents. By ovariectomizing these females during adolescence, the role of ovarian hormones in the long-term effects of Δ9-THC could also be examined as a systematic replication of the recent literature showing that ovarian hormones and cannabinoids likely interact at multiple levels (Gonzalez et al., 2000; Mize and Alper, 2000; Rodriguez et al., 1994; Winsauer et al., 2011). For example, Rodriguez et al. (1994) demonstrated that the presence or absence of sex steroids in rats differentially affected the density and/or affinity of cannabinoid receptors in distinct brain areas such as the striatum. In this area, cannabinoid receptor affinity was increased after ovariectomy (OVX), suggesting that ovarian hormones might constitutively inhibit cannabinoid binding in this area. Consistent with this possibility, 17β-estradiol administration in OVX rats was shown to significantly decrease GTPγS binding or the coupling of cannabinoid type-1 receptors (CB1R) to signal transduction pathways in the cortex and hippocampus (Mize and Alper, 2000), and estradiol in OVX rats significantly lowered mRNA levels for CB1R in the anterior pituitary gland compared to OVX females without estradiol administration (Gonzalez et al., 2000). However, the interaction of the cannabinoids and the hormone status of a female may depend on the age of the female, duration of the chronic administration, and the brain region. As an example of this, Winsauer et al. (2011) recently demonstrated that intact female rats had higher CB1R levels in the hippocampus after chronic, adolescent, Δ9-THC administration than OVX females, suggesting that ovarian hormones are also capable of enhancing components of cannabinoid signaling.

In addition to addressing our hypothesis, the present study also sought to determine whether chronic Δ9-THC administration and OVX during adolescence affected molecular mechanisms beyond GTPγS binding (Breivogel et al., 1999; Mize and Alper, 2000; Rubino et al., 2000; Winsauer et al., 2011). Two important targets may be the phosphorylation status or activation of cAMP response-element binding protein (CREB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Chronic Δ9-THC, for example, has been shown to markedly attenuate the phosphorylation of CREB in hippocampus (Fan et al., 2010) and cerebellum (Casu et al., 2005) and this effect was mediated by CB1R in both areas. Furthermore, chronic Δ9-THC during adolescence produced a sex-dependent decrease in CREB phosphorylation (p-CREB) in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of adult females, but not males (Rubino et al., 2008). CREB is also important as a transcription factor for the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is thought to play a key role in synaptic plasticity, as well as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). ERK, on the other hand, can be activated in the hippocampus of mice after acute Δ9-THC administration (Derkinderen et al., 2003) and ERK inhibition has been shown to block a Δ9-THC-induced conditioned place preference (Valjent et al., 2001). Finally, Rubino et al. (2006) have hypothesized that the main role of Δ9-THC-induced ERK phosphorylation (p-ERK) in the striatum and cerebellum (as opposed to other areas such as the hippocampus) is the modulation of trafficking proteins involved in CB1R activity. This hypothesis would also be consistent with data from Filipeanu et al. (2011) showing that the over expression of AHA1, a co-chaperone of heat shock protein (HSP) 90, enhanced CB1R levels at the plasma membrane and the effects of CB1R stimulation on ERK 1/2 phosphorylation. Thus, in female rats that have been actively discriminating Δ9-THC from saline, characterizing these regulators of cannabinoid signaling after chronic Δ9-THC could be extraordinarily helpful in unraveling the molecular mechanisms that underlie its discriminative stimulus effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

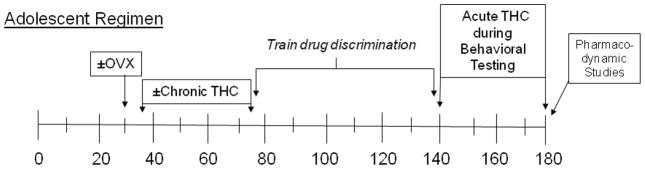

A total of 36 female Long-Evans rats, purchased in three separate cohorts of 12, served as subjects for this experiment. Each cohort was purchased from the same commercial vendor (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) as pups and arrived at the Animal Care facility on postnatal day (PD) 21. Following their arrival, the pups were group housed and provided a standard diet of rodent chow (Rodent Diet 5001, PMI Inc. St. Louis, MO) and water ad libitum until PD 30 when all the subjects were either ovariectomized or underwent a sham surgery (see Figure 1). After these procedures, the subjects were individually housed in polypropylene plastic cages with hardwood chip bedding and nestlets (Ancare, Bellmore, NY) to allow for recovery. Food restriction was also instituted at this time to maintain the compatibility of the treated groups; in this case, subjects were maintained at approximately 90% of their free-feeding weights while allowing for a gain of 5 grams per week to control for normal growth.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of manipulations for the subjects in each experimental group.

Throughout testing, the colony room was maintained at 21 ± 2° C with 50 ± 10% relative humidity on a 14L:10D light/dark cycle (lights on 06:00 h, lights off 20:00 h). The subjects used in these studies were maintained in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, and in compliance with the recommendations of the National Research Council in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996).

2.2 Adolescent ovariectomy

Subjects were ovariectomized while under general anesthesia and as previously described (Winsauer et al., 2011). Ovariectomy was also confirmed at the end of the study by visual inspection and uterine weight.

2.3 Adolescent administration of saline or Δ9-THC

From PD 35 to PD 75 (i.e., the beginning of adolescence to sexual maturity for most rats as indicated by Waynforth, 1992), both the OVX and intact (sham surgery) subjects received a single injection of either 5.6 mg/kg of Δ9-THC or saline intraperitoneally (i.p.) at the same time each day, yielding 4 experimental groups among each cohort of 12 with respect to hormone status and chronic Δ9-THC administration (i.e., intact/saline, intact/Δ9-THC, OVX/saline and OVX/Δ9-THC). The Δ9-THC was obtained from National Institute on Drug Abuse (Research Technical Branch, Rockville, MD), and prepared as described previously (Winsauer et al., 2011). When needed, aliquots of Δ9-THC were reconstituted for injection as an emulsion using ethanol, emulphor (Alkamuls EL-620, Rhodia, Inc., Cranbury, NJ), and saline in a proportion of 1:1:18. Saline alone rather than Δ9-THC vehicle was selected as the control for the chronic injections to reduce the possibility of i.p. irritation from repeatedly administering this emulsion, although this vehicle has not been found to produce this problem (unpublished observations). The volume for both saline and Δ9-THC injections was 0.1 ml/100 g body weight.

2.4 Apparatus

Twelve operant test chambers (6 from MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, and 6 from BRS/Foringer, Beltsville, MD) enclosed within sound-attenuating cubicles were used to conduct the experiments. Each chamber was equipped with a houselight, pellet trough, pellet dispenser, and two response levers with stimulus lights located above each lever. White noise was present in each chamber to mask extraneous noise and a fan provided ventilation. Data were collected using MED-PC for Windows, Version IV (MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT).

2.5 Training procedure

On PD 76 (beginning of adulthood), all of the treatment groups were trained to discriminate Δ9-THC from saline while responding under a fixed-ratio (FR) 20 schedule of food presentation. During the initial training sessions, the stimulus lights above both levers and the house light were illuminated, and a response on either lever dispensed a 45-mg food pellet (Test Diet, Richmond, IN). When subjects were responding reliably on at least one lever under this continuous reinforcement (CRF) schedule, they were then shaped to respond on only one lever per session by alternating the stimulus and lever that dispensed the pellets each session in a mixed order. The response requirement on each lever was also increased gradually during these training sessions until subjects responded under a FR-20 schedule. When responding on both levers stabilized under the FR-20 schedule, the stimuli over the levers were eliminated and injections of either saline or Δ9-THC were initiated. More specifically, saline or Δ9-THC was administered i.p. 20 min before the start of the session, which began with a 10-min timeout. The 10-min timeout period was followed by a 30-min period during which the houselight was illuminated and responding under the FR-20 schedule resulted in food presentation. Injections occurred in a fixed sequence that was repeated throughout the experiment (Δ9-THC [T], Saline [S], S, T, S, T, T, S, T, S) and each injection served as the discriminative stimulus for the appropriate lever (i.e., saline served as the discriminative stimulus for responding on one lever, whereas Δ9-THC served as the discriminative stimulus for responding on the other lever). For half of the rats in each adolescent-treated group, responding on the left lever resulted in food presentation following the administration of Δ9-THC, and responding on the right lever resulted in food presentation following the administration of saline; the lever designations were reversed for the other half of the subjects. Responding on the incorrect lever (i.e., the saline-associated lever following administration of Δ9-THC or the Δ9-THC-associated lever following administration of saline) had only one programmed consequence, which was resetting the ratio requirement on the correct lever. Training continued until subjects met two criteria on 9 of 10 consecutive days: 1) greater than 90% responding on the appropriate lever, and 2) less than 20 responses on the incorrect lever prior to the first reinforcement.

In all subjects, the initial training dose of Δ9-THC was 1 mg/kg; however, if this dose had an inordinately large effect on response rate, the training dose was decreased in quarter-log unit increments until a dose was reached that did not decrease the overall rate of responding. If the 1-mg/kg dose did not decrease response rate, and there was no evidence the subject was discriminating between injections of saline and Δ9-THC, the training dose was increased in quarter-log unit increments until the training criteria were met. In a few instances, the training dose was also increased after a subject had met the training criteria, because the training dose was not accurately discriminated under test conditions (see below). Test sessions with other doses of Δ9-THC commenced after the subjects met the training criteria.

2.6 Test sessions

Test sessions were conducted similarly to daily training sessions; however, 20 responses on either lever resulted in presentation of a food pellet. Substitution tests with different doses of Δ9-THC were conducted during these sessions to determine dose-effect curves for Δ9-THC. The discriminative stimulus effects of saline and Δ9-THC vehicle were also assessed routinely under test conditions. After substitution tests, subjects were always required to meet the training criteria for 3 consecutive days.

2.7 Western blot analyses

When the Δ9-THC dose-effect curves for the subjects in each experimental group were completed, each gonadally intact female was sacrificed with one OVX female from the respective adolescent treatment groups (saline or Δ9-THC) when the intact member of the pair was in proestrus to control for the effects of circulating levels of endogenous hormones across the estrous cycle. After sacrifice, the brains were rapidly removed and stored at −80°C. The striatum and hippocampus were separated from the other brain areas as described by Glowinski and Iversen (1966) prior to any biochemical analyses, and the levels of CB1R, p-CREB, and pERK in these areas were determined by western blotting of brain homogenate as described by Filipeanu et al. (2004, 2011). The sources for the antibodies were as follows: CB1R was from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI), p-ERK 1/2, total-ERK 1/2 and β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), and p-CREB and total-CREB were from Cell Signaling Technology, Incorporated (Danvers, MA).

2.8 Data analyses

To determine if there were significant differences among the groups in either the training dose that was required to establish the discrimination or the number of training days, two-way ANOVA tests were conducted on these data with hormonal status and adolescent drug treatment serving as factors. The data for each session were expressed as the percentage of responses on the lever for which Δ9-THC was serving as a discriminative stimulus (i.e., “Δ9-THC-lever” responding) and overall response rate in responses per second. Group data for each variable were expressed as a grand mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) that was tabulated by averaging the mean data for each subject; however, due to individual differences in potency of Δ9-THC’s rate-decreasing effects (particularly at the larger doses) not all doses were studied in all subjects, which led to differences in the number of subjects represented by each data point. Although this is not unusual in drug discrimination studies, differing numbers of subjects for certain drug doses can complicate the statistical analyses, particularly for repeated measures. In the present study, two-way ANOVA tests were used to analyze Δ9-THC-lever responding and response rate within the intact and OVX groups, with chronic treatment serving as a between subjects factor and dose of Δ9-THC serving as a repeated measure. In cases where there were missing values, such as for Δ9-THC-lever responding, the statistical software defaults to a General Linear Model of analysis whereby the sum of squares is estimated to produce a marginal sum of squares (SigmaPlot Software, SYSTAT Software, Inc. Point Richmond, CA). One advantage of this model is that it does not eliminate the assumption of a possible interaction between factors. Typically, full substitution in drug discrimination studies is considered to be 80% drug-lever responding or more, whereas a 20% increase or decrease from control is considered to be an effect on response rate. The percentage of Δ9-THC-lever responses was not included in the analyses when the response rate was less than 0.08 responses/sec. To further characterize and compare the dose-effect curves for Δ9-THC-lever responding, the doses that generated a 50% increase in Δ9-THC-lever responding (ED50s) were estimated. The ED50 values were determined by linear regression using two or more data points that reflected the ascending portion of the individual dose-effect curves. Differences in the slopes of the linear regressions were also reported in tabular form (Tables 1 and 2), and both the ED50 values and slopes were considered significantly different from control when the mean fell outside of the 95% confidence interval for the respective intact group.

Table 1.

Training dose, as well as the ED50 and slope of the dose-effect curve for the percentage of drug-lever responding, for the intact females in each chronically-treated group.

| Intact/Saline | Intact/THC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subj. | TD | ED50 | slope | Subj. | TD | ED50 | slope |

| 595 | 1 | 0.42 | 99.72 | 584 | 1.8 | 0.24 | 100 |

| 597 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 47.78 | 599 | 1 | 0.43 | 91.47 |

| 722 | 1.8 | 0.32 | 49.99 | 609 | 1.8 | 0.62 | 49.65 |

| 734 | 1.8 | 0.19 | 56.54 | 723 | 1.8 | 0.35 | 23.75 |

| 736 | 1.8 | 0.44 | 28.85 | 738 | 1.8 | 0.42 | 98.97 |

| 824 | 1 | 0.29 | 17.61 | 825 | 1 | <0.10 | |

| 836 | 1 | 0.42 | 99.81 | 840 | 0.56 | 0.42 | 97.74 |

| 838 | 1 | 0.32 | 49.95 | ||||

| Mean | 0.53 | 56.28 | 0.41 | 76.93 | |||

| 95% CI | 0.09–0.96 | 31.44–81.12 | 0.28–0.54 | 42.97–110.8 | |||

Table 2.

Training dose, as well as the ED50 and slope of the dose-effect curve for the percentage of drug-lever responding, for the OVX females in each chronically-treated group.

| OVX/Saline | OVX/THC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subj. | TD | ED50 | slope | Subj. | TD | ED50 | slope |

| 580 | 1.8 | <0.1 | 598 | 3.2 | 0.59 | 49.57 | |

| 592 | 1.8 | 0.19 | 49.84 | 608 | 1.8 | <0.1 | |

| 719 | 3.2 | 0.57 | 19.96 | 737 | 1.8 | 0.55 | 49.49 |

| 731 | 3.2 | 0.75 | 29.98 | 828 | 1 | 0.47 | 21.27 |

| 821 | 1 | 0.34 | 23.43 | 839 | 0.56 | 0.17 | 49.99 |

| 833 | 1 | <0.1 | 849 | 1 | 0.18 | 25.22 | |

| 845 | 1 | <0.1 | |||||

| Mean | 0.46 | 30.80* | 0.39 | 39.11† | |||

| 95% CI | 0.07–0.86 | 9.55–52.05 | 0.14–0.64 | 21.04–57.18 | |||

<indicates that the ED50 could not be calculated because it was likely below the lowest dose tested; therefore, these subjects were not included in the mean value presented.

indicates a significant difference from the confidence interval for the control group (i.e., OVX/saline)

indicates a significant difference from the confidence interval for the respective hormone condition (i.e., intact/Δ9-THC)

3. Results

Of the 36 subjects, 8 were excluded from the analyses as 5 had complications associated with their hormone status (e.g., partial ovariectomy), 2 were never able to successfully meet the training criterion, and 1 had to be euthanized due to illness unrelated to the experiment. For the remaining 28 subjects that comprised the 4 experimental groups, the Δ9-THC discrimination was successfully acquired and there were no significant main effects or significant interactions among the four groups for either the training dose that was required to establish the discrimination (hormone status: F(1,24)=1.22, p=0.28; chronic treatment: F(1,24)=0.29, p=0.60; interaction: F(1,24)=0.27, p=0.61) or the mean number of training days that were required to meet the training criterion (hormone status: F(1,24)= 0.40, p=0.53; chronic treatment: F(1,24)=0.475, p=0.50; interaction: F(1,24)=0.29, p=0.59). The mean and SEM for the number of training days was 52.25 ± 9.06 for the intact/saline group, 71.43 ± 23.43 for the intact/Δ9-THC group, 50.86 ± 11.42 for the OVX/saline group, and 53.17 ± 7.16 for the OVX/Δ9-THC group. Table 1 shows the training doses at which the subjects from each group reliably discriminated between saline and Δ9-THC.

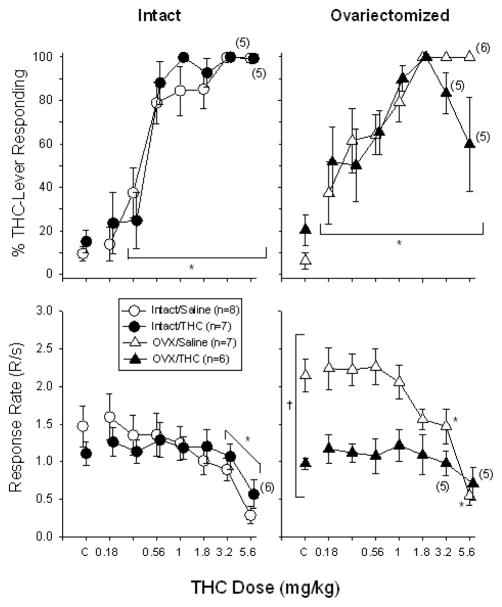

As shown in the upper left-hand panel of Figure 2, substituting increasing doses of Δ9-THC (0.18–5.6 mg/kg) produced dose-dependent increases in Δ9-THC-lever responding compared to saline substitution in all of the adolescent-treated groups; however, there were notable differences between the intact and OVX groups in Δ9-THC-lever responding and the overall response rate. In intact females, increasing doses of Δ9-THC produced a marked transition between saline-lever responding at low doses (0.18–0.32 mg/kg) and Δ9-THC-lever responding at high doses (0.56–5.6 mg/kg), irrespective of their adolescent treatment (Δ9-THC or saline). This observation was supported statistically, as there was no significant effect of chronic treatment (F(1,85)=0.34, p>0.05) and no significant interaction between chronic treatment and the doses that produced Δ9-THC-lever responding (F(7,85)=0.72, p>0.05). There was, however, a main effect of dose (F(7,85)=43.33, p<0.001), and post hoc analyses indicated that 0.32–5.6 mg/kg produced Δ9-THC-lever responding that was significantly different from Δ9-THC-lever responding after saline administration (i.e., control injections).

Fig. 2.

Effects of Δ9-THC on the percentage of Δ9-THC-lever responding (upper panels) and overall response rate (lower panels) in adult female rats that received chronic Δ9-THC (intact/Δ9-THC), ovariectomy (OVX/saline), or both (OVX/Δ9-THC) during adolescence. The control group received a sham surgery and chronic saline during adolescence (intact/saline). Subjects in each group discriminated different training doses while responding under a FR-20 schedule of food reinforcement (see Table 1). Doses of Δ9-THC were administered i.p. 20 min before the start of the session, which began with a 10-min timeout. Data points and vertical lines above “C” in each panel represent the grand mean and SEM for each group, which was calculated from the means for 4 to 11 injections of saline or vehicle for each subject in that group. The data points and vertical lines in the dose-effect curves for each group in each panel also represent a grand mean and SEM. The grand mean and SEM for each dose was calculated from the means for 1 to 5 determinations of that dose in each subject. Numerical values in parentheses and adjacent to a data point indicate the number of subjects represented by that point when it differed from the total number of subjects for that group. Asterisks along with a bracket indicate doses of Δ9-THC that were significantly different from saline administration (control) for both chronically-treated groups as there was neither a main effect of chronic treatment nor an interaction. Asterisks without a bracket indicate doses of Δ9-THC that were significantly different from saline administration (control) for a particular group. A cross with a bracket indicates the only dependent measure for which there was a significant main effect of chronic treatment.

Increasing doses of Δ9-THC in OVX females (upper right-hand panel) also dose-dependently increased Δ9-THC-lever responding irrespective of their chronic treatment during adolescence (i.e., Δ9-THC or saline). This was also verified statistically in that there was only a main effect of dose (F(7,73)=15.08, p<0.001), with no effect of chronic treatment (F(1,73)=0.09, p>0.05) and no significant interaction between these factors (F(7,73)=1.38, p>0.05). Unlike the effects of Δ9-THC in the intact females, however, even the lowest dose tested (0.18 mg/kg) produced Δ9-THC-lever responding that was significantly different than responding after saline administration (p<0.05) and successive doses increased Δ9-THC-lever responding in a more graded manner. This difference in the dose-effect curves between hormone groups is also reflected in the significant difference in the slopes of curves, as the mean slope for the OVX/saline group fell outside of the 95% confidence interval for the intact/saline group, and the mean slope for the OVX/THC group fell outside of the 95% confidence interval for the intact/THC group (see Tables 1 and 2). No significant difference in the ED50s was evident as the mean values the different groups were similar. For example, the ED50s for the intact groups were 0.53 and 0.41 mg/kg for the saline- and Δ9-THC-treated groups, respectively, whereas the ED50s for the OVX groups were 0.46 and 0.39 mg/kg, respectively.

In terms of the overall response rate for the intact groups (lower left-hand panel of Figure 2), mean response rate during control (saline or vehicle substitution) sessions generally reflected mean response rate during their training sessions. The mean response rate for the intact/saline group was 1.47 ± 0.27 responses per second, whereas the mean response rate for the intact/Δ9-THC group was 1.11 ± 0.15 responses per second. When compared to these mean values, increasing doses of Δ9-THC produced similar dose-dependent decreases in responding in both groups of intact females (F(7,89)=15.19, p<0.001), which indicates that the rate-decreasing effects of Δ9-THC were not altered by chronic treatment during adolescence (F(1,89)=0.04, p>0.05) and that there was no interaction between the dose of Δ9-THC and chronic adolescent treatment (F(7,89)=1.87, p>0.05). Further, because there was no interaction, the effects of dose were examined with the hormone groups combined and this post hoc analysis indicated that both the 3.2- and 5.6-mg/kg doses produced significant differences from the control rate of responding.

Compared to the mean response rates for the intact groups, which were similar under baseline conditions, the saline- and Δ9-THC-treated OVX groups had very different mean rates of responding during training sessions and after saline substitution (see lower right-hand panel of Figure 2). The mean and SEM for the OVX/saline group was 2.14 ± 0.22 responses per second, whereas the mean and SEM for the OVX/Δ9-THC group was 0.97 ± 0.08 responses per second. This difference in response rate between the two OVX groups was verified statistically by a two-way ANOVA that indicated there was a significant effect of chronic treatment (F(1,75)=10.43, p=0.008), a significant effect of dose (F(7,75)=11.86, p<0.001), and a significant interaction between chronic treatment and the dose of Δ9-THC administered (F(7,75)=4.09, p<0.001). Furthermore, post hoc analyses indicated that the 3.2- and 5.6-mg/kg doses were significantly different from control in the OVX saline group, but none of the doses of Δ9-THC had an effect on response rate in the OVX/Δ9-THC group.

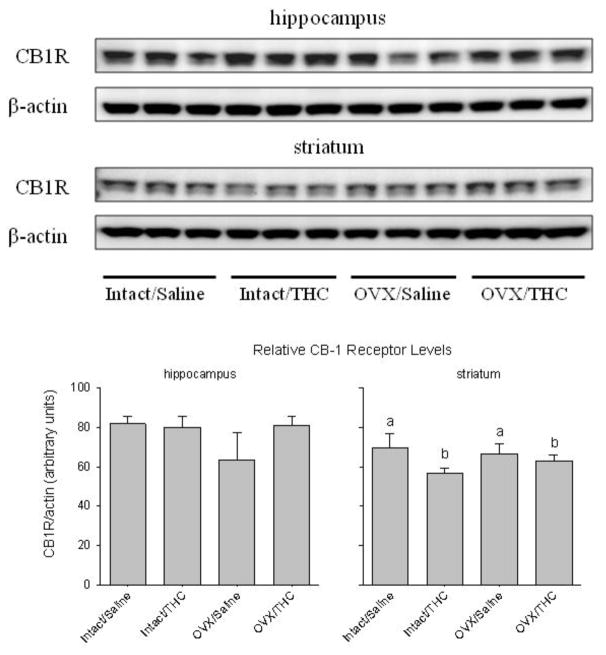

Figure 3 shows CB1R protein levels in both hippocampus and striatum as determined by Western blot, which detected CB1R as a major band of approximately 50 kDa. When normalized to β-actin, an internal control for the overall amount of protein, significant differences in CB1R levels were not apparent among the different treatment groups in hippocampus (hormone status: F(1,8)=3.59, p=0.095; chronic treatment: F(1,8)=2.89, p=0.13; interaction: F(1,8)=4.35, p=0.071), but they were apparent in striatum. More specifically, there was a significant effect of chronic treatment (F(1,8)=8.75, p=0.018), but no significant effect of hormone status (F(1,8)=0.28, p>0.05) and no significant interaction between hormone status and chronic treatment (F(1,8)=2.63, p>0.05).

Fig. 3.

Panel A shows CB1R protein expression in the hippocampus and striatum of adult female rats that received chronic Δ9-THC (intact/Δ9-THC), ovariectomy (OVX/saline), or both (OVX/Δ9-THC) during adolescence. The control group received a sham surgery and chronic saline during adolescence (intact/saline). The bar graphs in panel B show the quantification of CB1R levels when they are normalized to B-actin in the hippocampus and striatum. The letters in the bar graph for striatum represent the significant (p<0.05) main effect of Δ9-THC as indicated by a two-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak post hoc tests (i.e., a’s are significantly different from b’s, but not from each other).

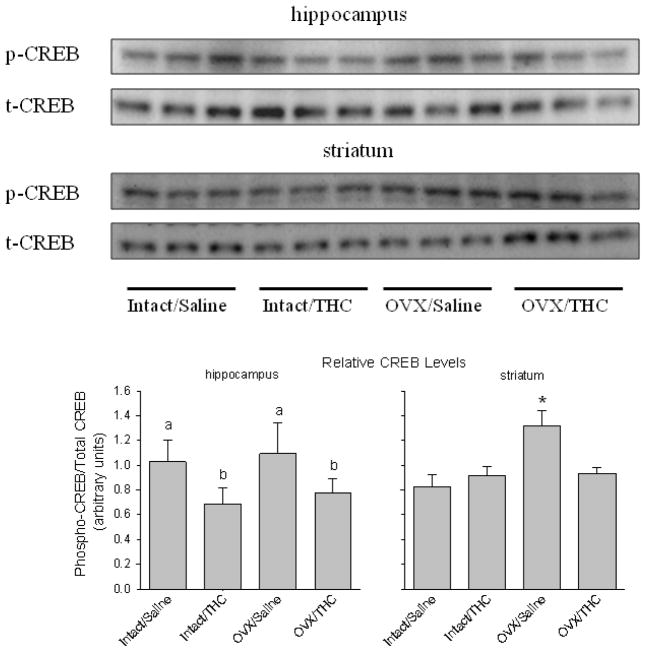

The effects of chronic adolescent treatment and hormone status on levels of p-CREB relative to the levels of total CREB (t-CREB) are shown in Figure 4. In contrast to CB1R levels, p-CREB levels in both the hippocampus and striatum were affected significantly, but in different ways. Chronic Δ9-THC during adolescence significantly decreased p-CREB levels in hippocampus (F(1,8)=10.85, p=0.011), whereas there was no effect of hormone status (F(1,8)=0.6, p>0.05) and no significant interaction between chronic treatment and hormone status in this area (F(1,8)=0.02, p>0.05). In striatum, there was a significant interaction between chronic adolescent treatment and hormone status (F(1,8)=22.67, p<0.001), and main effects of chronic treatment (F(1,8)=7.84, p=0.02) and hormone status (F(1,8)=20.32, p=0.002). Subsequent post hoc analyses that included a one-way ANOVA to compare the different experimental groups with the control group (intact/saline) indicated that p-CREB levels in the OVX/saline group were significantly larger than levels in the control group (F(3,8)=16.94, p<0.001); however, neither group that received chronic Δ9-THC had p-CREB levels that significantly differed from control.

Fig. 4.

Panel A shows the levels of p-CREB and t-CREB in the hippocampus and striatum of adult female rats that received chronic Δ9-THC (intact/Δ9-THC), ovariectomy (OVX/saline), or both (OVX/Δ9-THC) during adolescence. The control group received a sham surgery and chronic saline during adolescence (intact/saline). The bar graphs in panel B show the quantification of p-CREB in the hippocampus and striatum as a ratio of p-CREB to t-CREB. Letters in the left-hand graph for the hippocampus represent the significant (p<0.05) main effect of Δ9-THC as indicated by a two-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak post hoc tests. The asterisk in the right-hand graph for the striatum represents the significant difference from control (intact/Saline), which was established by a post hoc test conducted after a significant interaction was obtained with a two-way ANOVA.

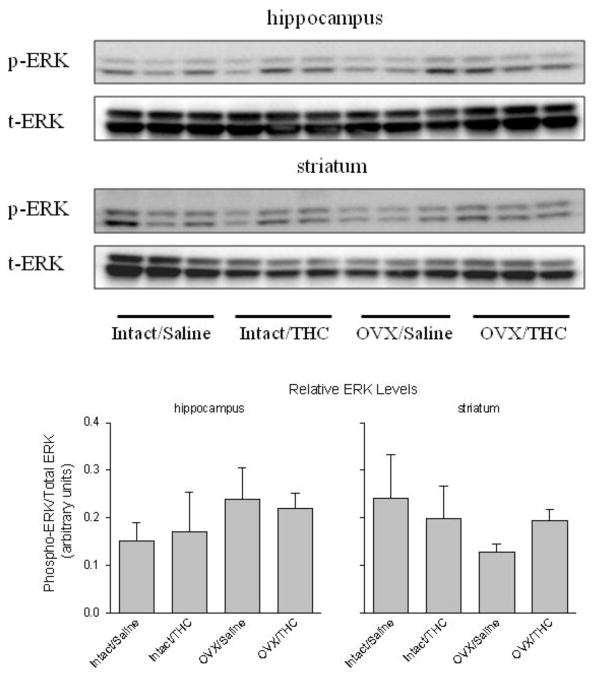

Figure 5 shows the levels of p-ERK relative to the levels of total ERK (t-ERK) in both hippocampus and striatum where there were no significant effects of chronic treatment (hippocampus: F(1,8)=0.00, p>0.05; striatum: F(1,8)=0.11, p>0.05) or hormone status (hippocampus: F(1,8)=3.93, p>0.05; striatum: F(1,8)=2.88, p>0.05), and no significant interaction between these treatments (hippocampus: F(1,8)=0.32, p>0.05; striatum: F(1,8)=2.53, p>0.05).

Fig. 5.

Panel A shows the levels of p-ERK 1/2 and t-ERK 1/2 in the hippocampus and striatum of adult female rats that received chronic Δ9-THC (intact/Δ9-THC), ovariectomy (OVX/saline), or both (OVX/Δ9-THC) during adolescence. The control group received a sham surgery and chronic saline during adolescence (intact/saline). The bar graphs in panel B show the quantification of p-ERK in the hippocampus and striatum as a ratio of p-ERK to t-ERK. A two-way ANOVA indicated there were no significant main effects of OVX or chronic Δ9-THC, and no significant interaction between these two factors.

4. Discussion

The main finding from the present study involving female rats was that chronic Δ9-THC during adolescence significantly affects both its discriminative stimulus and rate-decreasing effects for extended periods of time after the cessation of chronic administration (i.e., into adulthood). Furthermore, the effects on these two behavioral measures occurred concomitantly with effects on CB1R density and CREB phosphorylation in specific brain areas. These data complement and extend data in the literature suggesting that chronic Δ9-THC during adolescence produces persistent behavioral and pharmacodynamic effects (Fehr et al., 1976; O’Shea et al., 2006; Quinn et al., 2008), and data indicating that these effects may be dependent upon hormone status in female rats (Gonzalez et al., 2000; Rubino et al., 2008; Winsauer et al., 2011).

Although both Δ9-THC and estradiol have been shown to affect learning and memory individually in mammals (Daniel, 2006; Lichtman and Martin, 1996; Winsauer et al., 1999), there is remarkably little data regarding the interaction of these ligands (Daniel et al., 2002), and even less data on the possibility that their interactive effects may be age dependent. Because our laboratory had already investigated the interactive effects of these substances on acquisition and performance behavior (Daniel et al., 2002; Winsauer et al., 2011), this investigation focused on how they might interact to alter the discriminative stimulus effects of Δ9-THC. To that end, adolescent female rats in this study received the same chronic regimen of Δ9-THC as that used in Winsauer et al. (2011), and were trained to discriminate Δ9-THC from saline immediately afterward. Given that the dose used to establish a Δ9-THC discrimination can influence the extent to which subsequent test doses (or test drugs) generalize to the conditioned subjective effects (Jarbe et al., 1998), training dose was incorporated as a dependent variable. Another reason for using training dose as a dependent measure was that there was no substantial drug-free period after chronic administration for behavioral training as in the prior study, and females continued to receive Δ9-THC 2–3 times per week while acquiring the discrimination. Though allowing training dose to vary among subjects is somewhat unusual in drug discrimination procedures, there was the possibility that selecting a predetermined training dose might have overshadowed or eliminated any differences in sensitivity that resulted from the adolescent treatments. This concern was unfounded, however, as the dose of Δ9-THC that produced stable discrimination behavior did not differ by more than two fold in the vast majority of subjects (Table 1), and varied similarly across the treatment groups.

While dose-dependent increases in Δ9-THC-lever responding have been shown previously for rats (Alici and Appel, 2004; Jarbe et al., 1998; Wiley et al., 1995), pigeons (Mansbach et al., 1996), and non human primates (Gold et al., 1992; Wiley et al., 1993b; Wiley et al., 1995), an increase in Δ9-THC-lever responding at doses lower than the training dose in the OVX groups relative to the intact groups has not been shown previously. Typically, dose-effect functions for drug-lever responding in drug discrimination procedures are quantal in nature (Colpaert et al., 1976); that is, intermediate levels of responding (greater than 20% and less than 80%) usually reflect differences among subjects rather than intermediate levels of responding by individual subjects. This was also true in the present study as the small, graded increases in Δ9-THC-lever responding in both of the OVX groups did not reflect intermediate levels of responding by individual subjects, but rather an increased variability among subjects in the lowest dose that was reliably discriminated as similar to the training dose, and in the variability produced by a given dose in those subjects. As a result, the slopes of the dose-effect curves were significantly different for the OVX and intact groups, and this difference reflected the increased variability in the discriminative stimulus effects of Δ9-THC in OVX female rats.

With respect to response rate, the present results were consistent with a previous study by Winsauer et al. (2011) showing that the OVX/Δ9-THC group was the least sensitive to the rate-decreasing effects of Δ9-THC in adulthood. More specifically, 3.2 and 5.6 mg/kg decreased response rate in the intact groups and the OVX/saline group, but not in the OVX/Δ9-THC group. An effect that was not observed previously was the significant difference in response rates under control conditions between the two OVX groups. In fact, in the previous adolescent study, there was a much larger difference between the mean baseline response rates for the intact groups than the OVX groups, and the two OVX groups had significantly higher response rates than the intact groups. To what extent the differences between studies can be explained by the differences in Δ9-THC administration (continued subchronic administration immediately after chronic administration versus an extend drug free period after chronic administration), the behavioral task (acquisition and performance versus a conditional discrimination), or differences in signaling are unknown and need to be investigated further.

There were also differences between studies in the effects of adolescent Δ9-THC on CB1R levels, which were surprising given that the same chronic regimen of Δ9-THC was used. In the present study, chronic Δ9-THC during adolescence did not alter adult CB1R levels in the hippocampus, but reduced them significantly regardless of hormone status in the striatum. This result contrasts with our previous study where CB1R were decreased significantly in both OVX groups in striatum and increased selectively in the intact/Δ9-THC group. Interestingly, those effects were fairly consistent with the behavioral effects that were observed. In the present study, for example, the decrease in CB1R levels in the striatum could explain the lack of a rate-decreasing effect in the OVX/Δ9-THC group, if a strong relationship between response rate in a discrimination procedure and striatum-mediated motor activity exists. Why the same insensitivity to Δ9-THC’s rate-decreasing effects was not obtained in intact/Δ9-THC group after CB1R levels were reduced remains to be investigated. One possibility could be that the significantly higher response rate under control conditions in this group was more susceptible to the rate-decreasing effects of Δ9-THC.

Unlike the effects of chronic Δ9-THC on CB1R levels, which were limited to the striatum, chronic Δ9-THC significantly decreased p-CREB in the hippocampus regardless of hormone status, and significantly interacted with hormone status in the striatum (i.e., p-CREB was increased in the OVX/saline group whereas no increase occurred in the OVX/Δ9-THC group). Though acute and chronic Δ9-THC administration have been reported to produce different effects on p-CREB (e.g., Casu et al., 2005; Fan et al., 2010; Rubino et al., 2006), chronic Δ9-THC administration for 7 days or more has been shown to decrease p-CREB in the cerebellum (Casu et al., 2005) and hippocampus (Fan et al., 2010) of rodents. Δ9-THC has also been shown to disrupt hippocampally-mediated LTP and LTD (Fan et al., 2010; Misner and Sullivan, 1999), as well as many behavioral tasks that are mediated by the hippocampus (Deadwyler et al., 1995; Hampson and Deadwyler, 2000; Heyser et al., 1993; Lichtman et al., 1995). Moreover, antagonism studies with the CB-1 antagonist, SR141716A, have demonstrated that most of these Δ9-THC-induced behavioral effects (Hampson and Deadwyler, 2000; Lichtman and Martin, 1996), and the Δ9-THC-induced effects on p-CREB (Fan et al., 2010), are mediated by CB1R. One of the important downstream proteins modulated by CREB-dependent transcription is the neurotrophin BDNF, which plays a key role in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity in the adult brain. Provided p-CREB served a similar role in this study, the present data suggest that chronic Δ9-THC may also decrease neuronal plasticity during adolescence (Rubino et al., 2009), and reciprocally implicate the decrease in p-CREB as a contributing factor.

Interestingly, the levels of striatal p-CREB in the four treatment groups closely matched the differences in baseline response rates for these groups; that is, p-CREB and the baseline response rate was significantly higher for the OVX/saline group than for the other three groups. In addition, if chronic Δ9-THC decreases p-CREB in certain brain areas as reported previously (Casu et al., 2005; Fan et al., 2010), this would explain why the OVX/THC group had a p-CREB level and response rate similar to intact groups. Unfortunately, the increase in p-CREB in the OVX/saline group would not be consistent with a fairly large literature showing that estradiol administration in OVX females, as opposed to OVX alone, generally increases p-CREB in many brain regions (Carlstrom et al., 2001; Fan et al., 2008; Sharma et al., 2007). Though this raises a number of interesting issues concerning the effects of adolescent OVX on CREB-dependent transcription in various brain regions, the results obtained from hippocampus and striatum do support data in the literature indicating that these areas are differentially affected by hormone status and chronic Δ9-THC, and that desensitization of cannabinoid signaling in these areas may have different time courses (McKinney et al., 2008; Romero et al., 1998), and initiate different signaling cascades (Rubino et al., 2006). In general, there is a consensus that decreases in CBR uncoupling or desensitization likely precede receptor downregulation, and both of these phenomenon precede changes in mRNA expression (Gonzalez et al., 2005).

Finally, unlike the levels of CB1R and p-CREB, levels of p-ERK 1/2 were not significantly affected by OVX, chronic treatment, or their interaction. This was surprising given the hypothesized role for ERK in the modulation of CB1R trafficking in the striatum and cerebellum (Derkinderen et al., 2003; Valjent et al., 2001), and its suspected role in receptor desensitization during the development of physiological and behavioral tolerance (Daigle et al., 2008; Rubino et al., 2006). Possible reasons for the lack of an effect on ERK 1/2 include the fact that chronic Δ9-THC had ceased much earlier in the study (i.e., during adolescence) and that tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of most drugs, including Δ9-THC, does not seem to readily develop (Wiley et al., 1993a).

In summary, chronic Δ9-THC during adolescence produced effects alone and in combination with ovarian hormone status that altered the discriminative stimulus of Δ9-THC and its rate-decreasing effects in adult female rats. These behavioral effects were also concomitant with persistent alterations in CB1R levels in the striatum, and p-CREB levels in both the striatum and hippocampus as measured by western blot analyses. No statistically significant effects were obtained for levels of p-ERK 1/2. Together, both the long-term behavioral and pharmacodynamic effects of adolescent Δ9-THC administration in female rats suggests that cannabinoid abuse by adolescent human females likely affects their subsequent responsiveness to cannabinoids as adults and could have serious consequences for brain development.

Highlights.

Animal model to assess the relationship between adolescent and adult drug abuse.

Discriminative stimuli of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) were assessed.

Ovarian hormones (OVX) modified effects of chronic THC in adolescent female rats.

Adolescent OVX and chronic THC affected the molecular protein CREB, but not ERK.

OVX and chronic THC differentially affected the striatum and hippocampus.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS grant DA019625 (P.J.W.) and DA031596 (C.M.F.) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alici T, Appel JB. Increasing the selectivity of the discriminative stimulus effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol: complete substitution with methanandamide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL, Prescott WR. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol discrimination in rats as a model for cannabis intoxication. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Childers SR, Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Vogt LJ, Sim-Selley LJ. Chronic delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol treatment produces a time-dependent loss of cannabinoid receptors and cannabinoid receptor-activated G proteins in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2447–2459. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlstrom L, Ke ZJ, Unnerstall JR, Cohen RS, Pandey SC. Estrogen modulation of the cyclic AMP response element-binding protein pathway. Effects of long-term and acute treatments. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;74:227–243. doi: 10.1159/000054690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casu MA, Pisu C, Sanna A, Tambaro S, Spada GP, Mongeau R, Pani L. Effect of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on phosphorylated CREB in rat cerebellum: an immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 2005;1048:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC, Niemegeers CJ, Janssen PA. Theoretical and methodological considerations on drug discrimination learning. Psychopharmacologia. 1976;46:169–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00421388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle TL, Kearn CS, Mackie K. Rapid CB1 cannabinoid receptor desensitization defines the time course of ERK1/2 MAP kinase signaling. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel JM. Effects of oestrogen on cognition: what have we learned from basic research? J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:787–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel JM, Winsauer PJ, Brauner IN, Moerschbaecher JM. Estrogen improves response accuracy and attenuates the disruptive effects of delta9-THC in ovariectomized rats responding under a multiple schedule of repeated acquisition and performance. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:989–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Mu J, Whyte A, Childers S. Cannabinoids modulate voltage sensitive potassium A-current in hippocampal neurons via a cAMP-dependent process. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:734–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkinderen P, Valjent E, Toutant M, Corvol JC, Enslen H, Ledent C, Trzaskos J, Caboche J, Girault JA. Regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by cannabinoids in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2371–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02371.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Hanbury R, Pandey SC, Cohen RS. Dose and time effects of estrogen on expression of neuron-specific protein and cyclic AMP response element-binding protein and brain region volume in the medial amygdala of ovariectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;88:111–126. doi: 10.1159/000129498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan N, Yang H, Zhang J, Chen C. Reduced expression of glutamate receptors and phosphorylation of CREB are responsible for in vivo Delta9-THC exposure-impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J Neurochem. 2010;112:691–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr KA, Kalant H, LeBlanc AE. Residual learning deficit after heavy exposure to cannabis or alcohol in rats. Science. 1976;192:1249–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.1273591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipeanu CM, Guidry JJ, Leonard ST, Winsauer PJ. Delta9-THC increases endogenous AHA1 expression in rat cerebellum and may modulate CB1 receptor function during chronic use. J Neurochem. 2011;118:1101–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipeanu CM, Zhou F, Claycomb WC, Wu G. Regulation of the cell surface expression and function of angiotensin II type 1 receptor by Rab1-mediated endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41077–41084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowinski J, Iversen LL. Regional studies of catecholamines in the rat brain. I. The disposition of [3H]norepinephrine, [3H]dopamine and [3H]dopa in various regions of the brain. J Neurochem. 1966;13:655–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb09873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Balster RL, Barrett RL, Britt DT, Martin BR. A comparison of the discriminative stimulus properties of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and CP 55,940 in rats and rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:479–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S, Bisogno T, Wenger T, Manzanares J, Milone A, Berrendero F, Di MV, Ramos JA, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ. Sex steroid influence on cannabinoid CB(1) receptor mRNA and endocannabinoid levels in the anterior pituitary gland. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:260–266. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez S, Cebeira M, Fernandez-Ruiz J. Cannabinoid tolerance and dependence: a review of studies in laboratory animals. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:300–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Cannabinoids reveal the necessity of hippocampal neural encoding for short-term memory in rats. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8932–8942. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08932.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyser CJ, Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on delayed match to sample performance in rats: alterations in short-term memory associated with changes in task specific firing of hippocampal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:294–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman SG. Discriminative stimulus effects of drugs: Relationship to potential for abuse. In: Adler MW, Cowan A, editors. Testing and Evaluation of Drugs of Abuse. Vol. 6. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jarbe TU, Hiltunen AJ, Mechoulam R. Subjectively Experienced Cannabis Effects in Animals. Drug Dev Res. 1989;16:385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Jarbe TU, Lamb RJ, Makriyannis A, Lin S, Goutopoulos A. Delta9-THC training dose as a determinant for (R)-methanandamide generalization in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;140:519–522. doi: 10.1007/s002130050797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Dimen KR, Martin BR. Systemic or intrahippocampal cannabinoid administration impairs spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:282–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02246292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Martin BR. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol impairs spatial memory through a cannabinoid receptor mechanism. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;126:125–131. doi: 10.1007/BF02246347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Rovetti CC, Winston EN, Lowe JA., III Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A on the behavior of pigeons and rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:315–322. doi: 10.1007/BF02247436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney DL, Cassidy MP, Collier LM, Martin BR, Wiley JL, Selley DE, Sim-Selley LJ. Dose-related differences in the regional pattern of cannabinoid receptor adaptation and in vivo tolerance development to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:664–673. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misner DL, Sullivan JM. Mechanism of cannabinoid effects on long-term potentiation and depression in hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6795–6805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06795.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mize AL, Alper RH. Acute and long-term effects of 17beta-estradiol on G(i/o) coupled neurotransmitter receptor function in the female rat brain as assessed by agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPgammaS binding. Brain Res. 2000;859:326–333. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01998-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea M, McGregor IS, Mallet PE. Repeated cannabinoid exposure during perinatal, adolescent or early adult ages produces similar longlasting deficits in object recognition and reduced social interaction in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:611–621. doi: 10.1177/0269881106065188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn HR, Matsumoto I, Callaghan PD, Long LE, Arnold JC, Gunasekaran N, Thompson MR, Dawson B, Mallet PE, Kashem MA, Matsuda-Matsumoto H, Iwazaki T, McGregor IS. Adolescent rats find repeated Delta(9)-THC less aversive than adult rats but display greater residual cognitive deficits and changes in hippocampal protein expression following exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1113–1126. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez dF, Cebeira M, Ramos JA, Martin M, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ. Cannabinoid receptors in rat brain areas: sexual differences, fluctuations during estrous cycle and changes after gonadectomy and sex steroid replacement. Life Sci. 1994;54:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero J, Berrendero F, Manzanares J, Perez A, Corchero J, Fuentes JA, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ, Ramos JA. Time-course of the cannabinoid receptor down-regulation in the adult rat brain caused by repeated exposure to delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Synapse. 1998;30:298–308. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199811)30:3<298::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Realini N, Braida D, Guidi S, Capurro V, Vigano D, Guidali C, Pinter M, Sala M, Bartesaghi R, Parolaro D. Changes in hippocampal morphology and neuroplasticity induced by adolescent THC treatment are associated with cognitive impairment in adulthood. Hippocampus. 2009;19:763–772. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Vigano’ D, Realini N, Guidali C, Braida D, Capurro V, Castiglioni C, Cherubino F, Romualdi P, Candeletti S, Sala M, Parolaro D. Chronic delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol during adolescence provokes sex-dependent changes in the emotional profile in adult rats: behavioral and biochemical correlates. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2760–2771. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Vigano D, Costa B, Colleoni M, Parolaro D. Loss of cannabinoid-stimulated guanosine 5′-O-(3-[(35)S]Thiotriphosphate) binding without receptor down-regulation in brain regions of anandamide-tolerant rats. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2478–2484. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino T, Vigano D, Premoli F, Castiglioni C, Bianchessi S, Zippel R, Parolaro D. Changes in the expression of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and beta-arrestins in mouse brain during cannabinoid tolerance: a role for RAS-ERK cascade. Mol Neurobiol. 2006;33:199–213. doi: 10.1385/MN:33:3:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Mehra RD, Dhar P, Vij U. Chronic exposure to estrogen and tamoxifen regulates synaptophysin and phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding (CREB) protein expression in CA1 of ovariectomized rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2007;1132:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Pages C, Rogard M, Besson MJ, Maldonado R, Caboche J. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced MAPK/ERK and Elk-1 activation in vivo depends on dopaminergic transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:342–352. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waynforth HB. Experimental and Surgical Technique in the Rat. London: Academic Press Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Barrett RL, Balster RL, Martin BR. Tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol. Behav Pharmacol. 1993a;4:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Barrett RL, Britt DT, Balster RL, Martin BR. Discriminative stimulus effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and delta 9–11-tetrahydrocannabinol in rats and rhesus monkeys. Neuropharmacology. 1993b;32:359–365. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Lowe JA, Balster RL, Martin BR. Antagonism of the discriminative stimulus effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in rats and rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsauer PJ, Daniel JM, Filipeanu CM, Leonard ST, Hulst JL, Rodgers SP, Lassen-Greene CL, Sutton JL. Long-term behavioral and pharmacodynamic effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in female rats depend on ovarian hormone status. Addict Biol. 2011;16:64–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsauer PJ, Lambert P, Moerschbaecher JM. Cannabinoid ligands and their effects on learning and performance in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10:497–511. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199909000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]