Abstract

The physiological role of the uracil nucleotide-preferring P2Y6 and P2Y4 receptors is still unclear, although they are widely distributed in various tissues. In an effort to identify their biological functions, we found that activation by UDP of the rat P2Y6 receptor expressed in 1321N1 human astrocytes significantly reduced cell death induced by tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα). This effect of UDP was not observed in non-transfected 1321N1 cells. Activation of the human P2Y4 receptor expressed in 1321N1 cells by UTP did not elicit this protective effect, although both receptors were coupled to phospholipase C. The activation of P2Y6 receptors prevented the activation of both caspase-3 and caspase-8 resulting from TNFα exposure. Even a brief (10-min) incubation with UDP protected the cells against TNFα-induced apoptosis. Interestingly, UDP did not protect the P2Y6-1321N1 cells from death induced by other methods, i.e. oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide and chemical ischemia. Therefore, it is suggested that P2Y6 receptors interact rapidly with the TNFα-related intracellular signals to prevent apoptotic cell death. This is the first study to describe the cellular protective role of P2Y6 nucleotide receptor activation.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Pyrimidines, G protein-coupled receptor, Phospholipase C, Cell death, Cytokines, TNFα, Caspase, Nucleotide receptor

1. Introduction

Extracellular nucleotides have a ubiquitous role as signaling molecules in addition to their intracellular functions. The receptors for extracellular nucleotides, P2 receptors, are divided into two subfamilies: G protein-coupled (P2Y) and ligand-gated ion channels (P2X) [1–3]. The P2Y receptors have seven transmembrane domains and activate PLC, via coupling to Gq/11 proteins. This, in turn, increases inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) production and intracellular calcium, and/or stimulation/inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Several members of the P2 nucleotide receptor family are activated by uracil nucleotides. These pyrimidine nucleotide-responsive receptors include P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptors, which are activated by UTP and UDP, respectively. P2Y2 receptors respond to activation by either ATP or UTP.

The P2Y6 receptors are widely distributed in the placenta, spleen, thymus, bones, lungs, intestine, smooth muscle, heart, and epithelia. This distribution is not indicative of specific physiological roles in organs or tissues [4–8], and particular functions are largely unexplained. Recently there have been several reports on cellular functions of P2Y6 receptors. In human THP-1 monocytic cells and 1321N1 astrocytoma cells, P2Y6 receptors stimulated interleukin-8 production [9]. UTP potentiated LPS-induced PGE2 release in J744 macrophages expressing P2Y6 receptors [10]. It was suggested that UTP-evoked noradrenaline release in cultures of rat superior cervical ganglia is mediated through P2Y6 receptor activation [11]. In rat pial arterioles, a combination of P2Y2-and P2Y6-like receptors was suggested to be responsible for the pyrimidine nucleotide-evoked sustained vasoconstriction [12].

Another subtype of nucleotide receptors, P2Y4, is activated by UTP, is insensitive to ADP and UDP, and in humans is antagonized by ATP. Its expression is found in the placenta, pancreas, lungs, and vascular smooth muscle [13–16]. In human colorectal carcinoma cells, P2Y2/P2Y4 receptors have been identified and indicated to be associated with the ATP-mediated control of cell proliferation [17]. In vestibular dark cell epithelium, P2Y4 receptors controlled K+ secretion [18]. The possible involvement of P2Y2/P2Y4 receptors in apoptosis in rat glomerular mesangial cells has also been suggested [19].

In an effort to identify their biological functions, we have now investigated the relationship of P2Y6 and P2Y4 receptors, expressed in the 1321N1 astrocytoma cell line, to cell death. Previously, we had studied the relationship between adenosine receptors and cell death phenomena [20]. In the present study, protective effects against apoptosis by UDP were found, and the mechanism of this modulation was probed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

1321N1 astrocytoma cells stably transfected with either rat P2Y6 (rP2Y6) or human P2Y4 (hP2Y4) receptors were provided by Dr. Robert Nicholas (University of North Carolina). myo-[3H]Inositol (20 Ci/mmol) was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Dowex AG 1-X8 resin was purchased from Bio-Rad. DMEM and FBS were from Life Technologies, Inc. Anti-caspase-3 (Asp175), anti-caspase-8 (1C12), HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG, and HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. TNFα was purchased from Biosource International. All other reagents were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Co.

2.2. Cell culture and preparation

1321N1 cells stably transfected with the rP2Y6 or hP2Y4 receptors were grown at 37° in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2/95% air in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL of penicillin, 100 mg/mL of streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. The cells were grown to ~60% confluence for the experiments.

2.3. Induction of apoptosis

One method used to induce apoptosis was subjecting the cells to chemical ischemia. Cellular ischemia was induced using chemicals that block respiration and the utilization of glucose [21]. rP2Y6-1321N1 or hP2Y4-1321N1 cells were washed with PBS and then incubated at 37° in chemical ischemia-inducing buffer (10 mM sodium azide, 10 mM 2-deoxyglucose, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.62 mM MgSO4, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) for 2 or 3 hr. Medium was replaced with fresh 10% serum-containing DMEM with or without UDP or UTP. Cell death was assessed 16 hr later.

Apoptotic cell death was also induced by oxidative stress. The cells were washed once with PBS and incubated at 37° in DMEM containing 3% BSA and 1 μM insulin without antibiotics for 1 hr. Hydrogen peroxide was added in appropriate concentrations. After an hour, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS with or without UDP or UTP. Cell death was assessed 16 hr later.

Finally, TNFα was used to induce apoptosis. Medium containing 5 μg/mL of cycloheximide was added to the cells grown to ~60% confluence. In all the experiments concerning TNFα-induced cell apoptosis, cycloheximide was included. The cells were treated with appropriate concentrations of TNFα for 4 or 16 hr. UDP or UTP was added as indicated in each figure. Cell death was assessed 16 hr later.

2.4. Degree of cell death

After the treatment, the cells in the supernatant and the cells detached by trypsin–EDTA were combined and centrifuged. The cells were washed with PBS once and resuspended at 2–5 × 105 cells/mL in PBS. The cell suspension was stained with a propidium iodide solution (final concentration; 2 μg/mL), and the numbers of unstained (live) and stained (dead) cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson).

2.5. Determination of sub-G1 population

The apoptotic fraction after the various treatments was quantified by analyzing the sub-G1 (sub-diploid) population following the method of Kim et al. [22]. After fixing with 2% formaldehyde, treating with trypsin followed by RNase and trypsin inhibitor, and staining with propidium iodide, the cells were applied to a FACSCalibur instrument to measure the fluorescence activity of propidium iodide-stained DNA.

2.6. Immunoblot analysis

The proteins from the cells were extracted using a lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, 120 mM NaCl, 40 mM Tris, pH 8.0). After SDS–PAGE, the protein bands were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes that were subsequently blocked with 5% powdered non-fat milk. These membranes were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies and for 1 hr with the HRP-linked secondary antibody. Immunoblots were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Pierce).

2.7. Determination of inositol phosphates

The amount of inositol phosphates was measured by a modification of the method of Kim et al. [22]. The P2Y6-1321N1 or P2Y4-1321N1 cells were grown to confluence in 6-well plates in the presence of myo-[3H]inositol (2 μCi/mL) for 24 hr. After an additional incubation of 20 min with 20 mM LiCl at room temperature, cells were treated with UDP or UTP for 30 min. The reaction was terminated upon aspiration of the medium and addition of cold formic acid (20 mM). After 30 min, supernatants were neutralized with NH4OH, and applied to Bio-Rad Dowex AG 1-X8 anion exchange columns. All of the columns were then washed with water followed by a 60 mM sodium formate solution containing 5 mM sodium tetraborate. Total inositol phosphates were eluted with 1 M ammonium formate containing 0.1 M formic acid, and the 3H counts were measured using a liquid scintillation counter. Pharmacological parameters were analyzed using the Prism program (version 3.0, GraphPAD).

3. Results

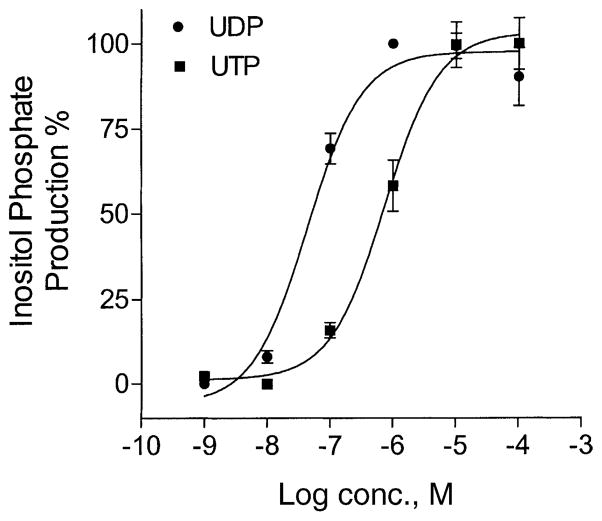

It has been reported that both P2Y6 and P2Y4 nucleotide receptors are coupled to PLC [23]. As shown in Fig. 1, the production of inositol phosphates in 1321N1 human astrocytes expressing the rP2Y6 receptor was increased by UDP in a concentration-dependent manner. The maximal effect was reached at 1 μM with an EC50 of 53.2 nM, similar to previous reports [23,24]. UTP also induced the production of inositol phosphates in hP2Y4-transfected 1321N1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 of 740 nM. This indicated that functional UDP-or UTP-responsive receptors linked to PLC were expressed in these cells.

Fig. 1.

Inositol phosphate production in P2Y6-or P2Y4-transfected 1321N1 human astrocytes. After being labeled with myo-[3H]inositol (1 μCi/106 cells) for 24 hr, the cells were treated for 30 min at 37° with agonists: UDP for P2Y6 or UTP for P2Y4. The amount of inositol phosphates was analyzed after extraction though Dowex AG 1-X8 columns (see “Section 2”). Data are means ± SD (N = 3). Where error bars are not visible, they are smaller than the symbol.

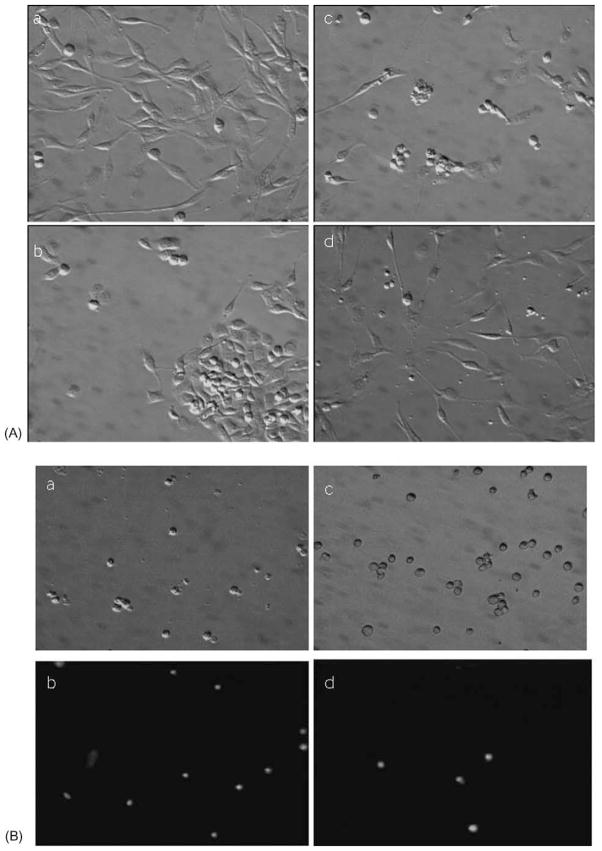

Death was induced in rP2Y6-1321N1 or hP2Y4-1321N1 cells by three different methods (chemical ischemia, oxidative stress, and death receptor activation by TNFα) for investigation of the effects of P2Y6 and P2Y4 receptor activation. Figure 2 shows the cellular morphology under these conditions. Chemical ischemia caused significant cell detachment and the formation of attached cell aggregates. After the induction of oxidative stress with 1 mM hydrogen peroxide, the cells appeared shrunken and displayed membrane blebbing. TNFα treatment (5 ng/mL) in the presence of 5 μg/mL of cycloheximide caused less disintegration of the cells than hydrogen peroxide treatment, but more fragmented cellular particles (apoptotic bodies) were observed. The morphological changes induced by each set of conditions were distinct, implying that the cell death mechanisms involved in each case were different. We observed that UDP antagonized TNFα-induced cell death in P2Y6-1321N1 cells and reduced the cell fragmentation (Fig. 2B). Microscopic examination of cells exposed to TNFα after detachment and propidium iodide staining indicated that UDP treatment decreased the fraction of cells stained. The activation of P2Y4 receptors in a similar line of stably transfected 1321N1 cells by UDP neither elicited morphological recovery nor protected against death in any of the three conditions.

Fig. 2.

Morphological changes of rP2Y6 receptor-transfected 1321N1 astrocytoma cells 16 hr after the treatments indicated (see “Section 2”): (A) a, non-treated adherent control cells; b, 3 hr of chemical ischemia; c, hydrogen peroxide (1 mM) for 1 hr; d, 5 ng/mL of TNFα with 5 μg/mL of cycloheximide. (B) Effect of UDP (10 μM) on TNFα (5 ng/mL)-induced cell death. Cells were detached and stained with propidium iodide. a, b: TNFα-treated cells; c, d: TNFα and UDP-treated cells; b, d; fluorescence micrographs of the fields of a and c, respectively.

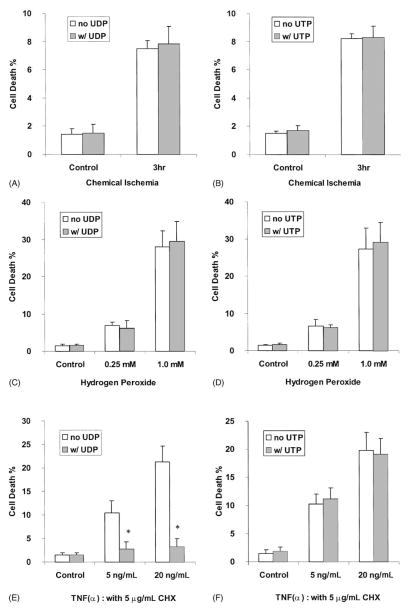

The cell death ratio was determined using FACS analysis following propidium iodide staining (Fig. 3). A 3-hr pulse-stress of 1321N1 cells with ischemia-causing chemicals increased the ratio of cellular detachment and cell death in rP2Y6-transfected 1321N1 human astrocytes. The activation of P2Y6 receptors by UDP in this cell line did not affect the detachment ratio or cell viability. The addition of UDP before or during the ischemic pulse-stress did not affect cell viability (data not shown). The cell death induced by hydrogen peroxide was 7:0 ± 0:8 and 28:0 ± 4:4% at 0.25 and 1.0 mM, respectively, after overnight incubation. In these cases, the treatment of the cells with UDP did not affect the cell death ratio. Activation of the hP2Y4 receptor in 1321N1 cells by the agonist UTP did not have preventive effects, either on chemical ischemia-or on hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of UDP or UTP on 1321N1 astrocytoma cells expressing rP2Y6 receptors (A, C, E) or hP2Y4 receptors (B, D, F). (A, B) Cells were incubated in an ischemia-inducing buffer (see “Section 2”) for 3 hr and restored to normal medium with or without 10 μM UDP or UTP. (C, D) Cells were treated with 0.25 or 1.0 mM hydrogen peroxide for 1 hr in DMEM containing 3% BSA, 1 μM insulin, and no antibiotics, and then returned to normal medium with or without 10 μM UDP or UTP. (E, F) Cells were treated with 5 or 20 ng/mL of TNFα in DMEM containing 3 μg/mL of cycloheximide (CHX) with or without 10 μM UDP or UTP. Sixteen hours after the treatments, the degree of cell death was analyzed using a FACSCalibur instrument. Data are means ± SD from the combined data of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Key: (*) statistically significant (P < 0:01) as determined by Student’s t-test.

Interestingly, however, we found that activation of the receptor by UDP (both at 1 and 10 μM at which the inositol phosphate production was maximal) in rP2Y6-transfected 1321N1 human astrocytes significantly reduced the apoptotic process induced by TNFα. With the sensitization by cycloheximide (5 μg/mL), exposure of P2Y6-1321N1 cells to 5 and 20 ng/mL of TNFα killed 10:5 ± 2:5 and 21:3 ± 3:3% of the total cell population, respectively. Activation of the P2Y6 receptor by UDP (10 μM) in the presence of TNFα (5 and 20 ng/mL) reduced cell death to 2:8 ± 1:5 and 3:2 ± 1:8%, respectively; i.e. ~70–80% inhibition in each case. In the concentration–response experiments, the EC50 for the protective effect of UDP against 20 ng/mL of TNFα was 13.9 nM. With a higher concentration of TNFα (80 ng/mL), cell death exceeded 50%, and the addition of UDP was not protective (data not shown). The protection by UDP was not observed in non-transfected 1321N1 astrocytes (data not shown). Furthermore, in human P2Y4-transfected 1321N1 astrocytes, UTP was not able to protect the cells from TNFα-induced death (Fig. 3).

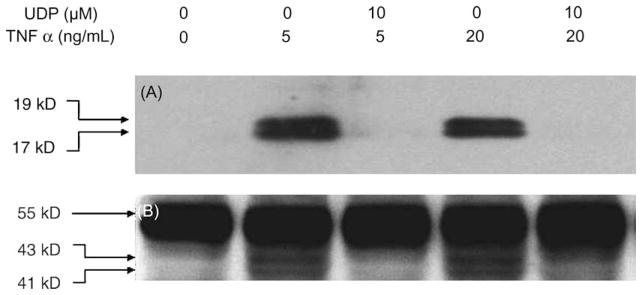

The apoptotic cell death induced by TNFα occurred through recruitment of caspase-8. Activated caspase-8 is known to cleave and activate additional downstream caspases including caspase-3, one of the key lethal mediators of apoptosis [25,26]. Six hours after the TNFα treatment of P2Y6 receptor-expressing 1321N1 cells, the cleavage of both caspase-3 and caspase-8 was observed. In the presence of 10 μM UDP, the activation of these caspases was inhibited significantly (Fig. 4). Measurement by flow cytometry of the sub-diploid fraction of the population indicated that 17 ± 4% of P2Y6-1321N1 cells were apoptotic following treatment with 20 ng/mL of TNFα. The addition of 10 μM UDP reduced the apoptosis ratio to the control level, 2:2 ± 1:2%. This suggested that a signal from the P2Y6 receptor interfered at some step(s) in the apoptotic pathway following TNFα receptor activation.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of TNFα-induced cleavage of caspase-3 (A) and caspase-8 (B) by P2Y6 receptor activation. The rP2Y6 receptor-expressing 1321N1 astrocytoma cells were treated with 5 or 20 ng/mL of TNFα in DMEM containing 3 μg/mL of cycloheximide in the absence or presence of 10 μM UDP. Six hours after the treatment, the proteins were extracted and immunoblotted as described in “Section 2.” (A) Large fragments of activated caspase-3 (17/19 kDa) are indicated. (B) Full-length caspase-8 (57 kDa) and the cleaved intermediate fragments (p43/41) are indicated. Results are representative of three experiments.

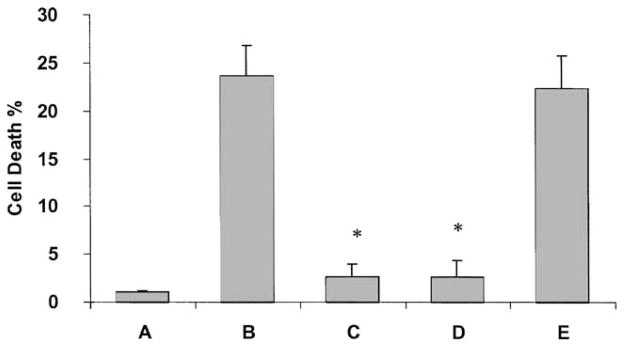

TNFα was able to induce cell death in 1321N1 cells even after a short period of treatment. The cells were incubated for only 4 hr with TNFα and further incubated in fresh medium for an additional 12 hr. After a 4-hr incubation, cell death was not observed (data not shown), but 12 hr later death occurred in 23 ± 3% of the cells, which was similar to the level of a 16-hr treatment with TNFα (Fig. 5). Upon a 4-hr incubation with TNFα, co-administered UDP was protective, reducing cell death to 2:7 ± 1:3%. The cells were also protected when preincubated with UDP for 10 min, washed with PBS, and then treated with TNFα for 4 hr. Interestingly, post-treatment with UDP, in which UDP was added 4 hr after the TNFα treatment, did not reverse the effect of TNFα. Therefore, it was suggested that UDP rapidly induced intracellular events that played a crucial role in preventing the cells from undergoing TNFα-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

Effects of UDP on short-term treatment of TNFα in rP2Y6 receptor-expressing 1321N1 cells. (A) Control cells. (B) Cells treated for 4 hr with TNFα. (C) Cells co-treated with both UDP and TNFα for 4 hr. (D) Cells incubated for 10 min with UDP, washed once with PBS, and then treated with TNFα for 4 hr (pretreatment). (E) Cells treated with TNFα for 4 hr and then the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing UDP (post-treatment). In each case, cell death was observed after an additional 12-hr incubation. The medium always contained 5 μg/mL of cycloheximide. The concentrations of UDP and TNFα were 1 μM and 20 ng/mL, respectively. The degree of cell death was analyzed using a FACSCalibur instrument. Data are means ± SD from the combined data of two independent experiments in triplicate. Key: (*) statistically significant (P < 0:01), as determined by Student’s t-test, compared with TNFα treatment (B).

4. Discussion

This is the first study to describe a role for P2Y6 nucleotide receptors in cellular protection. There have been several reports on the function of other P2Y receptors in cell death. The activation of P2Y1 receptors in 1321N1 cells decreased cell number and increased caspase-3-like activities [27]. It was proposed that P2Y2 and/or P2Y4 receptors in glomerular mesangial cells could induce proliferation and apoptosis, where the balance between proliferation and apoptosis would depend on the relative stimulation and expression of the P2 receptor subtypes [19]. The increase in PC12 cell death by extracellular ATP appeared to be through P2Y receptor activation [28]. In this study we investigated the action of recombinant rP2Y6 and hP2Y4 receptors in three different models: chemical ischemia, oxidative stress, and cell death receptor activation.

In ischemic conditions, the loss of oxygen and nutrient supply causes stress on cells by various pathways and eventually induces cell death. In the case of adenosine receptors, a significant physiological role in modulating ischemic damage to various tissues has been reported [29–37]. Recently, neuroprotection by the P2 receptor antagonist Basilen blue under hypoglycemic or chemically induced hypoxic conditions was reported [38]. We investigated the potential effects of P2Y6 and P2Y4 nucleotide receptor activation under ischemic conditions. However, activation of these receptors in our ischemic model was not protective (Fig. 3), in contrast to other nucleoside/nucleotide receptors in other models [29–38].

There have been reports on the role of nucleoside/nucleotide receptors in oxidative stress. The P2 receptor antagonists suramin and reactive blue 2 prevented dequalinium-induced neuronal death [39]. In chick retinal cells, an A1 adenosine agonist (CPA) and an A2A antagonist (DMPX) inhibited oxidative damage, while an A1 antagonist (DPCPX) and an A2A agonist (CGS 21680) potentiated damage [40]. It was reported that A1 receptor expression was increased by oxidative stress [41]. In the present study, activation of P2Y6 and P2Y4 receptors did not affect cell death in a model of oxidative stress (Fig. 3).

Among the three mechanistically different methods of inducing cell death, the administration of UDP to the P2Y6 receptor-expressing cells interfered with cell death only when induced by TNFα. TNFα has been known to induce apoptosis through the coupling of caspase-8 with TRADD, which, in turn, activates caspase-3 [25,26]. It was also suggested that activation by TNFα of JNK, p38, and nuclear factor-κB would result in crosstalk to this pathway, although the precise mechanism remains unclear [42]. Figure 4 demonstrated that the activation of P2Y6 receptors in 1321N1 cells by UDP drastically inhibited the cleavage of caspase-3 induced by TNFα, implying that the cell death induced by TNFα was apoptotic, and the signals from the receptor interfered with the apoptotic process to protect the cells. Since P2Y6 receptor activation also blocked cleavage of caspase-8, it appeared that the signal from P2Y6 receptor activation interfered with the death domain signaling upstream to, or at the level of caspase-8. The inhibition of caspase activation appeared to be responsible for the protection from cell death, as shown in Fig. 3.

Interestingly, activation of P2Y4 receptors by UTP did not have protective effects in TNFα-induced cell death. Both P2Y6 and P2Y4 have been known to activate PLC through coupling to the Gαq subunit of G proteins. Therefore, these two receptors would be expected to have had common intracellular pathways in order to elicit their biological functions, especially when expressed in the identical cell line. However, only P2Y6 receptors showed a protective effect in this astrocytoma cell line. Compared to P2Y6 receptors, P2Y4 receptors expressed in 1321N1 cells have been reported to desensitize very rapidly upon agonist exposure and to lose about 50% in surface expression within 10 min [43]. The P2Y4 receptor also showed a relatively rapid recovery rate following removal of UTP. The steadier and much slower turnover rate of P2Y6 receptors might be important for its observed protective effect.

To understand whether the signals from the receptor act at an early or late stage of the apoptotic pathway, we treated the cells with UDP prior to or following the addition of TNFα. In this case cell death was induced upon a short-term (4-hr) treatment with TNFα. Even though the residual UDP was washed away after a 10-min pretreatment, its protective signals persisted and prevented the cells from undergoing subsequent TNFα-induced death (Fig. 5). However, once the apoptotic signals were processed to some extent, UDP was not able to reverse the already initiated apoptosis. This implied that the P2Y6 receptor signal interacted in the early stages of TNFα signaling.

The involvement of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases in TNFα-induced apoptosis has been postulated. JNK has been reported to be responsible for death receptor-mediated cell death [25,42,44]. The activation of Erk appeared to regulate the death signal induced by the TNF receptor [45–47]. Overexpression of Erk prevented TNFα-induced apoptosis [48]. We have observed the increase of phospho-Erk by P2Y6 receptor activation (unpublished data). The involvement of PKC in death receptor-mediated TNFα-induced apoptosis is also known [49,50]. Since the P2Y6 receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) coupled to PLC, the activation of PKC by the receptor could be related to its biological effects [51].

In conclusion, the addition of UDP prevented cell death in rP2Y6 receptor-expressing 1321N1 astrocytoma cells only when it was induced by TNFα. Therefore, it is suggested that the P2Y6 receptor may interact with the TNFα-related intracellular signals to prevent apoptotic cell death. The precise mechanisms are under continuing investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Robert Nicholas of the University of North Carolina for providing the P2Y6 receptor-transfected cells. We thank Professor T.K. Harden of the University of North Carolina for helpful discussions. We thank Dr. Jane Trepel (National Cancer Inst., Bethesda, MD) for the use of instrumentation.

Abbreviations

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- PLC

phospholipase C

- Ab

antibody

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase

- and JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the Society for Neuroscience National Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, Nov. 11, 2001.

References

- 1.Barnard EA, Burnstock G, Webb TE. G-protein coupled receptors for ATP and other nucleotides: a new receptor family. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North RA. A family of ion channels with two hydrophobic segments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:474–83. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:413–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou M, Malmsjö M, Moller S, Pantev E, Bergdahl A, Zhao XH, Sun XY, Hedner T, Edvinsson L, Erlinge D. Increase in cardiac P2X1-and P2Y2-receptor mRNA levels in congestive heart failure. Life Sci. 1999;65:1195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somers GR, Bradbury R, Trute L, Conigrave A, Venter DJ. Expression of the human P2Y6 nucleotide receptor in normal placenta and gestational trophoblastic disease. Lab Invest. 1999;79:131–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somers GR, Hammet FM, Trute L, Southey MC, Venter DJ. Expression of the P2Y6 purinergic receptor in human T cells infiltrating inflammatory bowel disease. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1375–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schofl C, Ponczek M, Mader T, Waring M, Benecke H, von zur Muhlen A, Mix H, Cornberg MKH, Manns MP, Wagner S. Regulation of cytosolic free calcium concentration by extracellular nucleotides in human hepatocytes. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G164–72. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.1.G164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogdanov Y, Rubino A, Burnstock G. Characterisation of subtypes of the P2X and P2Y families of ATP receptors in the foetal human heart. Life Sci. 1998;62:697–703. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warny M, Aboudola S, Robson SC, Sevigny J, Communi D, Soltoff SP, Kelly CP. P2Y6 nucleotide receptor mediates monocyte interleukin-8 production in response to UDP or lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26051–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen BC, Lin WW. Pyrimidinoceptor potentiation of macrophage PGE2 release involved in the induction of nitric oxide synthase. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:777–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vartian N, Moskvina E, Scholze T, Unterberger U, Allgaier C, Boehm S. UTP evokes noradrenaline release from rat sympathetic neurons by activation of protein kinase C. J Neurochem. 2001;77:876–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis CJ, Ennion SJ, Evans RJ. P2 purinoceptor-mediated control of rat cerebral (pial) microvasculature; contribution of P2X and P2Y receptors. J Physiol (Lond) 2000;527:315–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Communi D, Pirotton S, Parmentier M, Boeynaems J-M. Cloning and functional expression of a human uridine nucleotide receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30849–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.30849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen T, Erb L, Weisman GA, Marchese A, Heng HHQ, Garrad RC, George SR, Turner JT, O’Dowd BF. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of the human uridine nucleotide receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30845–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.30845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb TE, Henderson DJ, Roberts JA, Barnard EA. Molecular cloning and characterization of the rat P2Y4 receptor. J Neurochem. 1998;71:1348–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogdanov YD, Wildman SS, Clements MP, King BF, Burnstock G. Molecular cloning and characterization of rat P2Y4 nucleotide receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;12:428–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Höpfner M, Lemmer K, Jansen A, Hanski C, Riecken E-O, Gavish M, Mann B, Buhr H, Glassmeier G, Scherübl H. Expression of functional P2-purinergic receptors in primary cultures of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:811–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcus DC, Scofield MA. Apical P2Y4 purinergic receptor controls K+ secretion by vestibular dark cell epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C282–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada H, Chan CM, Loesch A, Unwin R, Burnstock G. Induction of proliferation and apoptotic cell death via P2Y and P2X receptors, respectively, in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2000;57:949–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson KA, Hoffmann C, Cattabeni F, Abbracchio MP. Adenosine-induced cell death: evidence for receptor-mediated signalling. Apoptosis. 1999;4:197–211. doi: 10.1023/a:1009666707307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imura T, Shimohama S. Opposing effects of adenosine on the survival of glial cells exposed to chemical ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:539–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001115)62:4<539::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SG, Ravi G, Hoffmann C, Jung Y-J, Kim M, Chen A, Jacobson KA. p53-Independent induction of Fas and apoptosis in leukemic cells by an adenosine derivative, Cl-IB-MECA. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:871–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)00839-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholas RA, Watt WC, Lazarowski ER, Li Q, Harden K. Uridine nucleotide selectivity of three phospholipase C-activating P2 receptors: identification of a UDP-selective, a UTP-selective, and an ATP-and UTP-specific receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:224–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, Olesky M, Palmer RK, Harden TK, Nicholas RA. Evidence that the p2y3 receptor is the avian homologue of the mammalian P2Y6 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:541–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.3.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aggarwal BB. Tumour necrosis factors receptor associated signalling molecules and their role in activation of apoptosis, JNK, and NF-κB. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(Suppl 1):i6–16. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.suppl_1.i6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulze-Osthoff K, Ferrari D, Los M, Wesselborg S, Peter ME. Apoptosis signaling by death receptors. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:439–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sellers LA, Simon J, Lundahl TS, Cousens DJ, Humphrey PP, Barnard EA. Adenosine nucleotides acting at the human P2Y1 receptor stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinases and induce apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16379–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng Y, Wixom P, James-Kracke MR, Sun AY. Effects of extracellular ATP on Fe2+-induced cytotoxicity in PC-12 cells. J Neurochem. 1994;63:895–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63030895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee HT, Emala CW. Protective effects of renal ischemic preconditioning and adenosine pretreatment: role of A1 and A3 receptors. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:F380–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.3.F380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabuchi K, Ito Z, Wada T, Takahashi K, Hara A, Kusakari J. Effect of A1 adenosine receptor agonist upon cochlear dysfunction induced by transient ischemia. Hear Res. 1999;136:86–90. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neely CF, Keith IM. A1 adenosine receptor antagonists block ischemia-reperfusion injury of the lung. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L1036–46. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.6.L1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harada N, Okajima K, Murakami K, Usune S, Sato C, Ohshima K, Katsuragi T. Adenosine and selective A2A receptor agonists reduce ischemia/reperfusion injury of rat liver mainly by inhibiting leukocyte activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:1034–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakayama H, Yamamoto Y, Kume M, Yamagami K, Yamamoto H, Kimoto S, Ishikawa Y, Ozaki N, Shimahara Y, Yamaoka Y. Pharmacologic stimulation of adenosine A2 receptor supplants ischemic preconditioning in providing ischemic tolerance in rat livers. Surgery. 1999;126:945–54. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(99)70037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peralta C, Hotter G, Closa D, Prats N, Xaus C, Gelpi E, Rosello-Catafau J. The protective role of adenosine in inducing nitric oxide synthesis in rat liver ischemia preconditioning is mediated by activation of adenosine A2 receptors. Hepatology. 1999;29:126–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khimenko PL, Moore TM, Hill LW, Wilson PS, Coleman S, Rizzo A, Taylor AE. Adenosine A2 receptors reverse ischemia-reperfusion lung injury independent of β-receptors. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:990–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.3.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Lubitz DK, Lin RC, Boyd M, Bischofberger N, Jacobson KA. Chronic administration of adenosine A3 receptor agonist and cerebral ischemia: neuronal and glial effects. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;367:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00977-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobson KA, Xie R, Young L, Chang L, Liang BT. A novel pharmacological approach to treating cardiac ischemia. Binary conjugates of A1 and A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30272–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cavaliere F, D’Ambrosi N, Ciotti MT, Mancino G, Sancesario G, Bernardi G, Volonte C. Glucose deprivation and chemical hypoxia: neuroprotection by P2 receptor antagonists. Neurochem Int. 2001;38:189–97. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan CF, Lin-Shiau SY. Site of action of suramin and reactive blue 2 in preventing neuronal death induced by dequalinium. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:692–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001201)62:5<692::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agostinho P, Caseiro P, Rego AC, Duarte EP, Cunha RA, Oliveira CR. Adenosine modulation of D-[3H]aspartate release in cultured retina cells exposed to oxidative stress. Neurochem Int. 2000;36:255–65. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nie Z, Mei Y, Ford M, Rybak L, Marcuzzi A, Ren H, Stiles GL, Ramkumar V. Oxidative stress increases A1 adenosine receptor expression by activating nuclear factor κB. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:663–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang G, Minemoto Y, Dibling B, Purcell NH, Li Z, Karin M, Lin A. Inhibition of JNK activation through NF-κB target genes. Nature. 2001;414:313–7. doi: 10.1038/35104568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brinson AE, Harden TK. Differential regulation of the uridine nucleotide-activated P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptors. Ser-333 and Ser-334 in the carboxyl terminus are involved in agonist-dependent phosphorylation desensitization and internalization of the P2Y4 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11939–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Javelaud D, Besançon F. NF-κB activation results in rapid inactivation of JNK in TNFα-treated Ewing sarcoma cells: a mechanism for the anti-apoptotic effect of NF-κB. Oncogene. 2001;20:4365–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakagami H, Morishita R, Yamamoto K, Taniyama Y, Aoki M, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Kaneda Y, Horiuchi M, Ogihara T. Mitogenic and antiapoptotic actions of hepatocyte growth factor through ERK, STAT3, and AKT in endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2001;37:581–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valladares A, Álvarez AM, Ventura JJ, Roncero C, Benito M, Porras A. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates tumor necrosis factor-α-induced apoptosis in rat fetal brown adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4383–95. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yazlovitskaya EM, Pelling JC, Persons DL. Association of apoptosis with the inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase activity in the tumor necrosis factor α-resistant ovarian carcinoma cell line UCI 101. Mol Carcinog. 1999;25:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tran SE, Holmstrom TH, Ahonen M, Kahari VM, Eriksson JE. MAPK/ERK overrides the apoptotic signaling from Fas, TNF, and TRAIL receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16484–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li D, Yang B, Mehta JL. Tumor necrosis factor α enhances hypoxiareoxygenation-mediated apoptosis in cultured human coronary artery endothelial cells: critical role of protein kinase C. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:805–13. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laouar A, Glesne D, Huberman E. Involvement of protein kinase C-β and ceramide in tumor necrosis factor α-induced but not Fas-induced apoptosis of human myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23526–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim SG, Gao ZG, Soltysiak KA, Chang TS, Brodie C, Jacobson KA. Program No. 142.5 2002 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2002. P2Y6 nucleotide receptor protects 1321N1 astrocytoma cells against tumor necrosis factor α-induced apoptosis through activation of PKC. CD-ROM. [Google Scholar]