Abstract

Molecular evolution studies suggest that amelogenins (AMEL), the principal components of the mammalian enamel matrix, emerged considerably later than ameloblastin (AMBN), and enamelin. Here we have created a transgenic mouse model to ask the question how a conceivable basal enamel lacking AMEL and enriched in the more basal AMBN might compare to recent mouse enamel. To address this question we have overexpressed AMBN using a K14 promoter and removed AMEL from the genetic background by crossbreeding with AMEL−/− mice. Enamel coverings of AMEL−/− mice and of the squamate Iguana iguana were used for comparison. Scanning electron microscopic analysis documented that AMBN TG × amel−/− mouse molars were covered by a 5μm thin “enameloid” layer resembling the thin enamel of the Iguana squamate. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that the enamel of developing AMBN TG × amel−/−mouse molars contained approximately 70nm short and randomly oriented crystals, while WT controls, AMBN overexpressors, and AMEL−/− mice all featured elongated and parallel oriented crystals measuring between 300nm and 600nm in average length. Together, these studies illustrate that AMBN promotes the growth of a crystalline enamel layer with short and randomly oriented crystals, but lacks the ability to facilitate the formation of long and parallel oriented apatite crystals.

Keywords: enamel, amelogenin, ameloblastin, evolution, apatite

Tooth enamel crystals grow in an organic matrix rich in proteins. These proteins are commonly called enamel proteins and greatly affect the growth and habit of enamel crystals (1-3). Enamel proteins may control enamel crystal growth as nucleators (4), as spacers between individual crystallites (5,6), or as promoters of c-axis crystal elongation (1,3,5,7), but more likely in all of these capacities in a cooperative and sequential fashion. Ultrastructural, developmental, and evolutionary biology studies have demonstrated that the enamel matrix is not a uniform environment but rather a dynamic continuum in which enamel proteins, proteases, and spliced products of various lengths collaborate to form enamel crystals and that the composition of this continuum has changed throughout vertebrate evolution (8-10).

Many of the key proteins within the enamel matrix originated from an ancestral member of the secretory calcium binding phosphoprotein family (SCPP), which gave rise to enamelin, ameloblastin, and amelogenin through gene duplication and differentiation (11-13). The most recent and major enamel protein, amelogenin is believed to be have evolved from a gene ancestral to enamelin and ameloblastin by duplication and translocation onto a chromosomal region that belongs to the X-Y chromosomes of placental mammals (11,14,15). This continuous evolution of enamel proteins appears to correspond to a gradual increase in enamel complexity during the evolution of vertebrates with the emergence of enamel prisms during the reptilian mammalian transition (2,16,17). Higher order enamel structures in vertebrates have been linked to the rise of amelogenin enamel proteins (3,18) and the complexity of mammalian enamel microstructures have been associated with the multitude of mammalian amelogenin isoforms generated by alternative splicing and proteolytic processing (19).

The relatively recent position of amelogenin in the timing of enamel protein evolution poses the question about structure and properties of enamel without amelogenin. To address this question, we have focused on ameloblastin as the second most recent enamel protein from an evolutionary perspective (11). Loss of ameloblastin has resulted in a dramatic enamel phenotype that has been attributed to the failure of ameloblast attachment (20,21). Overexpression of ameloblastin in transgenic mice using an amelogenin promoter caused enamel disturbances resembling an Amelogenesis Imperfecta phenotype in humans (22). However, the effect of ameloblastin on enamel crystal growth remains to be explored.

Here we have generated an ameloblastin transgenic mouse model by driving ameloblastin overexpression with a robust Keratin 14 promoter (23). We have further crossed this ameloblastin overexpressor with an amelogenin null mouse (24) to remove the amelogenin background. The resulting offspring displayed an enamel matrix highly enriched in ameloblastin and devoid of amelogenin and therefore suitable to test the effect of ameloblastin in enamel crystal growth.

Material and Methods

Ambn Transgene and generation cross-breeding with amel−/− mice

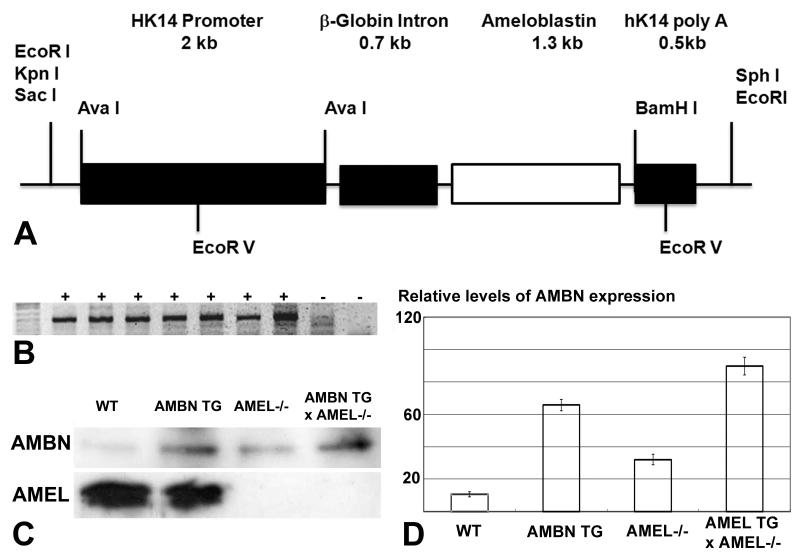

Transgenic constructs were generated using the human keratin-14 cassette construct (a generous gift from Dr. Elaine Fuchs, Rockefeller University) to overexpress the mouse Ambn coding region (Fig. 1). The 1269 bp Ambn coding region with a BamH1 site at the 3′ end and a Xho I site at the 5′ end was PCR-amplified. The Ambn gene was inserted between the β-Globin intron and the K14 poly-A signal. A β-Globin intron was used to ensure that the transgenes were transcribed properly. The transgenic fragments were freed from the construct by digesting the constructs with Sac I and Hind III, gel purified and microinjected into mouse zygotes (23). In total, 6 independent lines were generated. Germline transmission was determined by PCR analysis of genomic DNA obtained from tail biopsies. The Qiagen multiplex PCR kit (Valencia, Calif., USA) was used for PCR, which was performed using a set of specific primer for K14 promoters: a forward primer 5′-GCTTAGCCAGGGTGACAGAG-3′ and a reverse primer 5′-CACAGAGGCGTAAATGCAGA-3′. PCR products were analyzed on a 2.0% TAE agarose gel. Offspring mice carrying the Ambn transgene (Tg) were mated with Amelogenin null mice (24). F1 offspring positive for the transgene and heterozygous for amelogenin (amel+/−) were mated, yielding an F2 generation which was genotyped by tail biopsies. Altogether four groups were generated, including wild-type (WT), ameloblastin transgenic overexpression (AMBN TG), amelogenin null (amel−/−), and amelogenin null crossed with ameloblastin transgenic overexpression (AMBN TG × amel−/−).

Figure 1.

Generation of mutant mice expressing an ameloblastin enriched enamel matrix. (A) Construct used for the generation of AMBN overexpressing mice using a K14 promoter to drive the AMBN transgene. (B) PCR genotyping results for the identification of offspring carrying the AMBN transgene. (C) Western blot comparison of AMBN and AMEL expression between wild-type, AMBN overexpressor, AMEL null, and AMBN overexpressor crossed with AMEL null mice. (D) Densitometry evaluation of relative levels of AMBN expression. Values represent mean +/− standard deviation.

Western blot analysis for enamel matrix gene expression

Western blots using either anti-AMBN or anti-AMEL primary antibodies were performed to compare levels of AMBN and AMEL expression. Equal amount of protein was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane (Immobilon P®, Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membrane was either incubated with an affinity-purified antibody against mouse AMBN or AMEL at a concentration 1:200. Immune complexes were detected with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and enhanced by chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The amount of the protein expression was compared after normalization by the amount of β-actin as an internal calibrator in each lane.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies, 3 female mice in 30d postnatal from each group, WT, AMBN TG, amel−/−, and AMBN TG × amel−/−, were sacrificed according to UIC animal care guidelines. Lower mandibles were isolated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in 70% and 100% ethanol and then saggitally hemisected using an Exakt sawing device. The enamel surface was etched in EDTA for 5 min, rinsed thoroughly, and dried overnight. Samples were coated with gold and palladium and then examined using a JEOL JSM-6320F scanning electron microscope. The distal slope of the buccal second cusp was used for comparison. Prism width was measured directly from digital images. All measurements in this study were statistically evaluated using ANOVA and statistical dispersion was recorded and displayed using standard deviation (s.d.).

Transmission electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies, 3 animals aged 3 day postnatal from each group, WT, AMBN TG, amel−/−, and AMBN TG × amel−/−, were sacrificed. First lower molars were dissected under a dissecting microscope. Molar samples were fixed in 2 % (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 2 % (v/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 2-4 hours, and postfixed in 2 % (v/v) osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in cacodylate buffer, at pH 8. Subsequently, samples were dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol, and embedded in EMBed 812 epoxy resin (EMS, Hatfield, PA), following transitioning in propylene oxide. For TEM, 5 representative samples per group which were sectioned were selected and ultrathin sections were cut and floated on a trough pre-satuated with hydroxyapatite to slow the rate of possible mineral dissolution. Floating time of sections on water was minimized. The sections were then examined using a JEOL 1220 TEM microscope. Digital micrographs were recorded from 5 representative areas per section at 30K magnification, and crystals length was analyzed using ANOVA.

Results

Generation of mutant mice expressing an ameloblastin enriched enamel matrix that lacks amelogenin

Four different mouse models were used to determine the effect of AMBN on enamel crystal growth: (i) an AMBN overexpressing mouse in which the AMBN gene was driven by a Keratin 14 promoter, (ii) an AMBN overexpressing mouse crossed with an AMEL null mouse to remove the amelogenin background in the developing enamel matrix, (iii) an AMEL null mouse as a control for the loss of amelogenin, and (iv) a wild-type control of the same strain (FVB)(Fig. 1). Western blot analysis using our anti-ameloblastin antibody on mouse molar extracts revealed elevated levels of AMBN expression in AMBN transgenic mice as well as AMBN transgenic mice crossed with AMEL null mice, while expression levels in WT mice and AMEL null mice were relatively lower (Fig. 1). Specifically, AMBN protein levels in AMBN overexpressors were 6.5 fold higher compared to wild-type controls and AMBN protein expression in AMBN TG × amel−/− mice was 2.78-fold her than in AMEL null mice and 8.56-fold higher than in WT controls, as revealed by densitometry (Fig. 1). AMEL protein levels in a second set of Western blot results using amelogenin as the primary antibody demonstrated that neither the AMEL null mice nor the AMEL null mice crossed with AMBN overexpressor tested positive for amelogenin, while amelogenin was present in wild-type and un-altered AMBN overexpressor mice. Together, these results indicate that we have generated a mouse model (AMBN TG × amel−/−) with an enamel matrix enriched in AMBN and lacking AMEL.

Scanning electron microscopy of wild-type and AMBN enriched enamel matrix

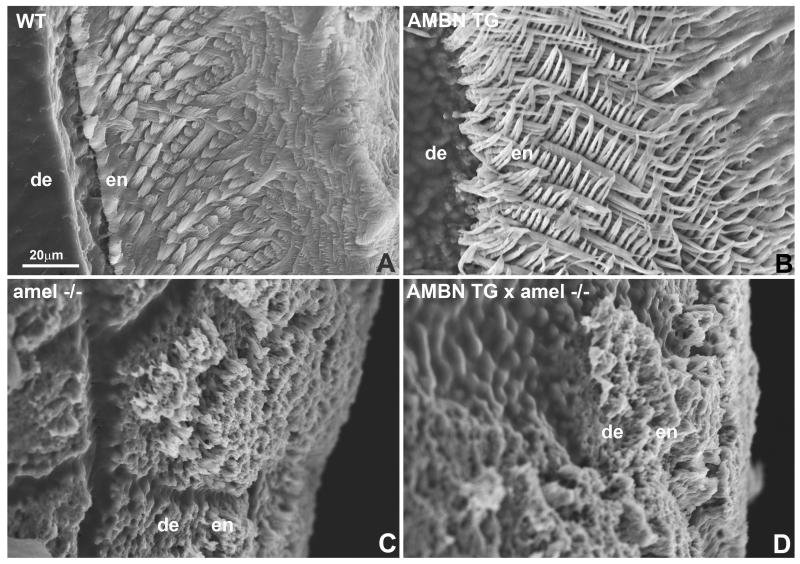

Scanning electron microscopic analysis was performed to compare the developing enamel of wild-type, AMBN overexpressor, AMEL null, and AMBN overexpressor crossed with AMEL null mice. Compared to the enamel of wild-type mice and AMBN overexpressors, the enamel thickness of AMEL null mice and those crossed between AMEL null and AMBN overexpressors was approximately 10-fold reduced and elaborate prism patterns were replaced by simple pyramids formed by individual crystals (Fig. 2). Moreover, there was a highly significant decrease in enamel prism diameter between WT controls and AMBN overexpressors from 2.38+/−0.51 μm to 1.32+/−0.34 μm (p<0.001)(Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrographs of etched mouse first mandibular molar distal slope enamel. Samples were from (A) wild-type, (B) AMBN overexpressor, (C) AMEL null, and (D) AMBN overexpressor crossed with AMEL null mice. en = enamel, de = dentin.

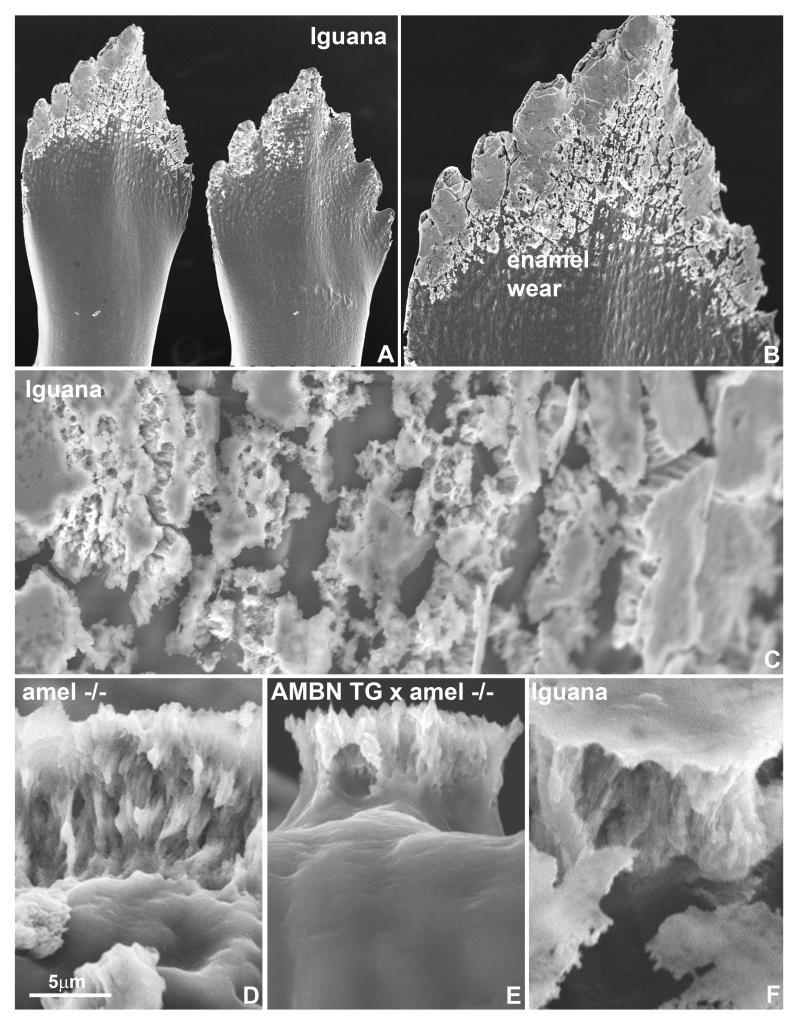

Comparison between Iguana enamel and mouse enamel lacking amelogenin

Scanning electron micrographs of Iguana iguana tooth crowns revealed a partial covering of the tip of the Iguana tooth crown with a thin layer of short enamel crystal patches (Fig. 3). At high magnification, Iguana enamel was organized into short, thin and perpendicular to the enamel surface oriented enamel crystal bundles, comparable in morphology to those found on the enamel surface of AMEL null mice and AMBN overexpressor crossed with AMEL null mice (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Scanning microscopical comparison between Iguana enamel and mutant mouse enamel. (A), (B) and (C) are scanning electron micrographs of Iguana iguana tooth crowns. Note the pronounced wear pattern on Iguana enamel surfaces (B) and the presence of a thin layer of short enamel crystal patches (C). (D-F) are Scanning electron micrographs taken tangentially to the crown surface of the enamel of AMEL null mice (D), AMBN overexpressor crossed with AMEL null mice (E), and Iguana (F). Bar = 5μm.

Transmission electron microscopical comparison between enamel crystal structure and organization from wild-type and AMBN overexpressing mice

Enamel crystals from AMBN overexpressors crossed with AMEL null mice were short and randomly oriented compared to enamel crystals from wild-type, AMEL null, and AMBN overexpressor controls (Fig. 4). AMBN TG × AMEL −/− crystals measured 72.2+/−22.9nm similar to Iguana crystals measuring 73.5+/−11.2 nm, while all three control groups featured significantly longer crystals, 322.5+/−92.1nm in the wild-type control, 542.3+/−143.2nm in the AMBN overexpressor, and 336.5+/−69.1nm in the AMEL null group. Differences in crystal dimension between wild-type and AMBN overexpressor were significant (p<0.01); and were highly significant (p<0.001) between wild-type and AMBN TG × AMEL −/−, and between wild-type mouse and Iguana. At high magnification, the short and randomly oriented enamel crystals in the AMBN overexpressor matrix resembled those in the enamel matrix of the Iguana (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of enamel crystal organization following transgenic modulation of the enamel matrix AMBN content in 3 days postnatal first mandibular mouse molars. (A) Wild-type, (B) AMBN overexpressor, (C) AMEL null (D) AMBN overexpressor crossed with AMEL null. Bar = 200nm for (A) – (F). (E-G) Comparison between high magnification electron micrographs of mouse enamel (E), AMBN overexpressor crossed with AMEL null enamel (F), and Iguana iguana enamel (G). Bar = 100nm for (G) – (I).

Discussion

In the present study transmission and scanning electron microscopy were used to study the influence of the enamel matrix protein ameloblastin on enamel crystal growth in transgenic mouse models. According to Western blot analysis, the K14 promoter driven AMBN construct resulted in strong AMBN overexpression in developing teeth, while the cross with AMEL null mice successfully removed the AMEL background. K14 expression in developing ameloblasts was confirmed in earlier studies (23) and the robust K14 promoter has been used successfully to drive transgene expression in epithelial tissues (25). The cross of a strong AMBN overexpressor with an AMEL null mouse resulted in the generation of a unique enamel matrix highly enriched in AMBN and devoid of AMEL, according to Western blot.

Evaluation of transmission electron micrographs demonstrated that enamel crystals in the AMBN enriched enamel matrix devoid of AMEL were short and randomly oriented compared to the long and parallel oriented crystals in controls. These data suggest that among enamel proteins, AMBN is not involved in enamel apatite crystal elongation along the c-axis and perhaps plays other roles in enamel crystal growth. Unlike AMBN, there have been numerous studies suggesting that AMEL is associated with c-axis crystal growth (1,3,5,7), especially due to its elongated PXX tri-peptide repeats. This hypothesis was confirmed here by the presence of long and parallel crystals both in the wild-type control and in the AMBN overexpressor, which both expressed amelogenin. Data presented here also revealed an unexpected growth of elongated and parallel enamel crystals in the AMEL null mouse. The AMEL null rudimentary enamel matrix contains both ENAM and AMBN among major enamel proteins, but no AMEL, suggesting that apart from amelogenin, enamelin might play a role in crystal elongation as suggested earlier (8,9).

Compared to an earlier study in which the AMEL promoter was used to drive the AMBN transgene (22), the enamel generated in our K14 promoter driven AMBN overexpressors featured enamel prisms of half the diameter of their wild-type counterparts. On an ultrastructural level, individual crystals were sharply delineated from intercrystalline protein matrix, a finding that was only exaggerated in the AMBN overexpressors lacking amelogenin. These data were somewhat in contrast with the reduction in rod architecture, the increase in interrod enamel crystal patterns, and the reduction in crystal length reported in an earlier study based on an AMEL promoter driven AMBN overexpressor (22). Neither the AMEL promoter of the previous study nor the K14 promoter employed here represent the gene-specific promoter that naturally controls AMBN expression, the AMBN promoter. The K14 promoter model used in the present study certainly benefits from AMBN overexpression during an extended period of amelogenesis and significant AMBN overexpression as demonstrated by Western blot. At least for the purpose of the present study, and in tandem with the cross with AMEL null mice, our K14 driven AMBN overexpressor proved to be a highly suitable model system to test the effect of an AMBN enriched matrix on hydroxyapatite crystal growth.

Comparative studies with developing Iguana enamel revealed that the short and randomly oriented crystals in the AMBN-rich enamel matrix exhibited a remarkable similarity with the short and randomly oriented enamel crystals of the squamate reptile Iguana iguana. The short and randomly oriented enamel crystals of AMBN overexpressors and the thin enamel layer of Iguana were representative of the enamel crystal organization found in the development enamel of many squamates (2,26). Based on earlier hypotheses on the relationship between ameloblasts and secreted matrix during enamel prism growth (27), it is likely that both cellular and biochemical factors play a role in the rapid change in crystal orientation and structure during the reptilian-mammalian transition. Biochemical factors include an increase of the percentage of amelogenins in the enamel matrix or a change in enamel protein processing and alternative splicing (19). Cellular factors involved in prism shape and growth may include Tomes’ processes (28) and the mechanisms that control its extension. As suggested earlier (27), biochemical and cellular factors may influence each other and depend on each other. Here we explain the similarities in enamel crystal structure between the developing Iguana enamel and the AMBN-rich enamel as a result of a higher percentage of AMBN in the developing Iguana matrix compared to its mammalian counterpart. Such an explanation is bolstered by the previously reported gradual increase of amelogenins in the developing enamel matrix at the expense of other enamel proteins during vertebrate evolution (8,9).

Acknowledgements

Funding for these studies by NIDCR grants DE13378 and DE18900 to TGHD and DE18057 to XL is gratefully acknowledged. The Keratin 14 promoter was a generous gift by Dr. Elaine Fuchs, Rockefeller University.

References

- 1.Diekwisch T, David S, Bringas P, Jr, Santos V, Slavkin HC. Antisense inhibition of AMEL translation demonstrates supramolecular controls for enamel HAP crystal growth during embryonic mouse molar development. Development. 1993;117:471–482. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diekwisch TG, Berman BJ, Anderton X, Gurinsky B, Ortega AJ, Satchell PG, Williams M, Arumugham C, Luan X, McIntosh JE, Yamane A, Carlson DS, Sire JY, Shuler CF. Membranes, minerals, and proteins of developing vertebrate enamel. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:373–395. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diekwisch TG, Jin T, Wang X, Ito Y, Schmidt M, Druzinsky R, Yamane A, Luan X. Amelogenin evolution and tetrapod enamel structure. Front Oral Biol. 2009;13:74–79. doi: 10.1159/000242395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarasevich BJ, Lea S, Bernt W, Engelhard MH, Shaw WJ. Changes in the quaternary structure of amelogenin when adsorbed onto surfaces. Biopolymers. 2009;91:103–107. doi: 10.1002/bip.21095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fincham AG, Moradian-Oldak J, Diekwisch TG, Lyaruu DM, Wright JT, Bringas P, Jr, Slavkin HC. Evidence for amelogenin “nanospheres” as functional components of secretory-stage enamel matrix. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:50–59. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moradian-Oldak J. Amelogenins: assembly, processing and control of crystal morphology. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:293–305. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Wang L, Qin Y, Sun Z, Henneman ZJ, Moradian-Oldak J, Nancollas GH. How amelogenin orchestrates the organization of hierarchical elongated microstructures of apatite. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:2293–2300. doi: 10.1021/jp910219s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herold R, Rosenbloom J, Granovsky M. Phylogenetic distribution of enamel proteins: immunohistochemical localization with monoclonal antibodies indicates the evolutionary appearance of enamelins prior to amelogenins. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;45:88–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02561407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satchell PG, Anderton X, Ryu OH, Luan X, Ortega AJ, Opamen R, Berman BJ, Witherspoon DE, Gutmann JL, Yamane A, Zeichner-David M, Simmer JP, Shuler CF, Diekwisch TG. Conservation and variation in enamel protein distribution during vertebrate tooth development. J Exp Zool. 2002;294:91–106. doi: 10.1002/jez.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diekwisch TGH, Wang X, Fan JL, Ito Y, Luan X. Expression and characterization of a Rana pipiens amelogenin protein. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:86–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sire JY, Delgado S, Fromentin D, Girondot M. Amelogenin: lessons from evolution. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawasaki K, Suzuki T, Weiss KM. Phenogenetic drift in evolution: the changing genetic basis of vertebrate teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18063–18068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509263102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki K, Weiss KM. SCPP gene evolution and the dental mineralization continuum. J Dent Res. 2008;87:520–531. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawasaki K, Weiss KM. Mineralized tissue and vertebrate evolution: the secretory calcium-binding phosphoprotein gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4060–4065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0638023100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawasaki K, Weiss KM. Evolutionary genetics of vertebrate tissue mineralization: the origin and evolution of the secretory calcium-binding phosphoprotein family. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2006;306:295–316. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sander M. Non-mammalian synapsid enamel and the origin of mamalian enamel prism: The bottom-up prespective. In: Koenigswald W.v., Sander PM., editors. Tooth Enamel Microstructure. A.A.Balkema; Rotterdam: 1997. pp. 40–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood CB, Dumont ER, Crompton AW. New studies of enamel microstructure in Mesozoic mammals: a review of enamel prisms as a mammalian synapomorphy. Journal of Mammologyalian Evolution. 1999;6:177–213. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satchell PG, Shuler CF, Diekwisch TG. True enamel covering in teeth of the Australian lungfish Neoceratodus forsteri. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;299:27–37. doi: 10.1007/s004419900132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathur AK, Polly The evolutioin of enamel microstructure: how important is amelogenin. J Mammal Evolution. 2000;7:23–42. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukumoto S, Kiba T, Hall B, Iehara N, Nakamura T, Longenecker G, Krebsbach PH, Nanci A, Kulkarni AB, Yamada Y. Ameloblastin is a cell adhesion molecule required for maintaining the differentiation state of ameloblasts. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:973–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wazen RM, Moffatt P, Zalzal SF, Yamada Y, Nanci A. A mouse model expressing a truncated form of ameloblastin exhibits dental and junctional epithelium defects. Matrix Biol. 2009;28:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paine ML, Wang HJ, Luo W, Krebsbach PH, Snead ML. A transgenic animal model resembling amelogenesis imperfecta related to ameloblastin overexpression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19447–19452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luan X, Ito Y, Diekwisch TG. Evolution and development of Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1167–1180. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson CW, Yuan ZA, Hall B, Longenecker G, Chen E, Thyagarajan T, Sreenath T, Wright JT, Decker S, Piddington R, Harrison G, Kulkarni AB. Amelogenin-deficient mice display an amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31871–31875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seitz CS, Lin Q, Deng H, Khavari PA. Alterations in NF-κB function in transgenic epithelial tissue demonstrate a growth inhibitory role for NF-κB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:2307–2312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Fan JL, Ito Y, Luan X, Diekwisch TGH. Identification and characterization of a squamate reptilian amelogenin gene: Iguana iguana. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2006;306:393–406. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osborn J. The mechanism of prism formation in teeth: a hypothesis. Calc Tiss Res. 1970;5:115–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02017542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanaizumi Y, Yokota R, Domon T, Wakita M, Kozawa Y. The initial process of enamel prism arrangement and its relation to the Hunter-Schreger bands in dog teeth. Arch Histol Cytol. 2010;73:23–36. doi: 10.1679/aohc.73.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]