Abstract

About 30 years ago, the first Dutch unifactorial guidelines on hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia were developed. These guidelines have been revised several times, often after publication of landmark studies on new generations of drugs. In 1978, cut-off points for pharmacological treatment of hypertension were based on diastolic blood pressure values ≥115 mmHg, and in 2000 they were lowered to >100 mmHg. From 1997 onwards, cut-off points for systolic blood pressure values >180 mmHg were introduced, which became leading. In 1987, cut-offs for hypercholesterolaemia of ≥8 mmol/l were set and from 2006 pharmacological treatment was based on a total/HDL cholesterol ratio >8. Around 2000, treatment decisions for hypertension and/or hypercholesterolaemia were no longer based on high levels of individual risk factors, but on a multifactorial approach based on total risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), determined by a risk function. In the 2006 multidisciplinary guideline on cardiovascular risk management, the Framingham risk tables were replaced by European SCORE risk charts. A cut-off point of 10% CVD mortality was set in the Netherlands. In 2011, this cut-off point changed to 20% fatal plus nonfatal CVD risk. Nowadays, ‘the lower the risk factors, the lower the absolute risk’ is the leading paradigm in CVD prevention.

Keywords: Blood pressure, Cardiovascular diseases, Cholesterol, Primary prevention, Risk tables

Introduction

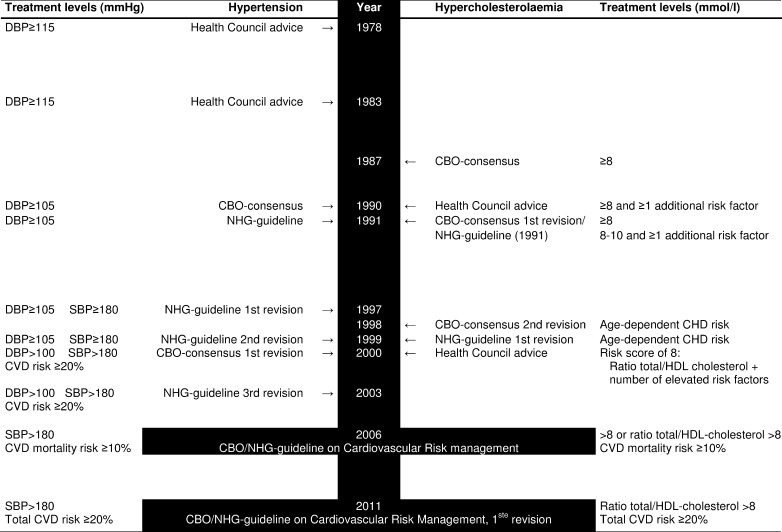

The Health Council of the Netherlands led the way on cardiovascular risk management 30 years ago by issuing advice on the treatment of hypertension [1, 2], followed by an advice on cholesterol [3]. At almost the same time, guidelines for hypertension and cholesterol were developed by the former Institute of Health Care Improvement (CBO) in cooperation with the Netherlands Heart Foundation (NHS) [4, 5]. The Netherlands College of General Practitioners (NHG) developed guidelines specifically for general practitioners [6, 7]. In 2006, the first guideline on integrated cardiovascular risk management was released, a collaborative activity involving the CBO, NHG and NHS [8–10]. Revision of guidelines took place after 2–8 years, depending on new developments, e.g. publication of landmark studies on new generations of drugs, or inspired by publications or updates of the World Health Organisation (WHO), and American or European guidelines. In the past 30 years, eight guidelines on hypertension [1, 2, 4, 6, 11–14], seven on cholesterol [3, 5, 15–18], and two on cardiovascular risk management have been published in the Netherlands (Figs. 1, 2) [8–10, 19].

Fig. 1.

Overview of guidelines on hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and cardiovascular risk management by year, and treatment levels. CBO Former Dutch Institute for Healthcare Improvement (Utrecht); NHG Dutch College of General Practitioners (Utrecht). CHD coronary heart disease; CVD cardiovascular diseases; DBP diastolic blood pressure; SBP systolic blood pressure, HDL cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

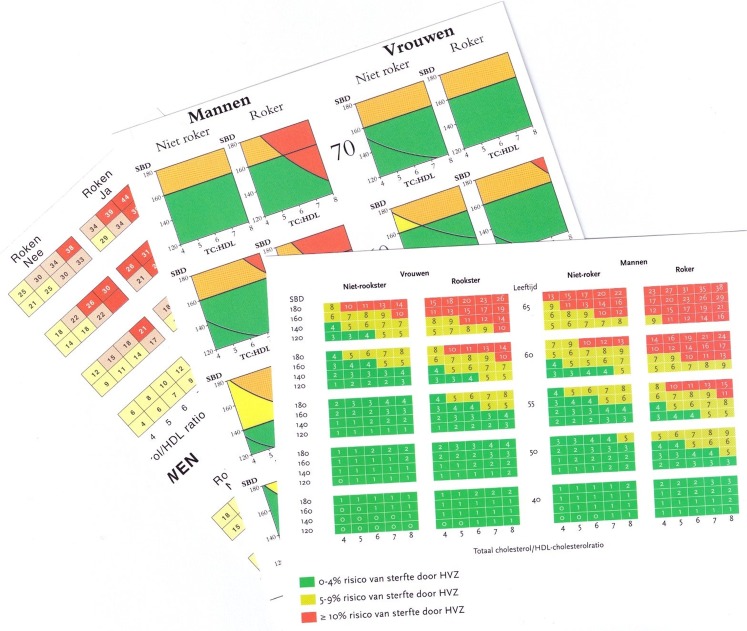

Fig. 2.

Impression of risk charts in the 1998 Guideline on Cholesterol, the 2000 Guideline on High blood pressure and the 2006 Guideline on Cardiovascular Risk Management

An historical overview is presented of Dutch guideline development on hypertension and cholesterol, lately integrated into cardiovascular risk management. Emphasis is on consensus guidelines for primary prevention, in high-risk persons without manifest cardiovascular diseases (CVD). The focus is on changes in blood pressure levels for drug treatment of hypertension, on cholesterol levels for drug treatment of hypercholesterolaemia and on the introduction of risk charts to identify persons at high risk of CVD.

Guidelines on hypertension 1978–2003

The first advice on the treatment of hypertension was published by the Health Council (1978, 1983) [1, 2]. Hypertension was defined as a diastolic blood pressure of 115 mmHg or higher. Persons with hypertension were advised to change their lifestyle and were eligible for drug treatment. Persons with blood pressure values between 100 and 115 mmHg were eligible for drug treatment, when lifestyle measures did not effectively lower blood pressure. First-choice drugs were diuretics (thiazides) and beta-blockers. These recommendations were based on the results of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program from the USA [20] and the Australian therapeutic trial on mild hypertension [21].

New insights into the risk of moderately elevated blood pressure levels [22] were the justification for the lower thresholds of drug treatment in the 1990 CBO/NHS consensus [4] and the 1991 NHG guideline [6]. Now persons with diastolic blood pressure levels exceeding 105 mmHg were eligible for drug treatment. Persons with levels between 95 and 104 mmHg were treated only when additional risk factors were present, e.g. smoking, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, high body mass index (BMI) or a positive family history of CVD. The presence of one additional risk factor was recommended in the CBO guideline, and two in the NHG guideline. For pharmacological treatment, four classes of drugs were available: diuretics, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors and calcium antagonists. At that time, there was only definitive evidence that the first two classes of antihypertensives reduced CVD incidence in patients with hypertension.

In the 1990s, several meta-analyses of trials in persons with hypertension were published [23, 24]. Evidence was accumulating that treatment of systolic hypertension reduced CVD incidence, also in the elderly. The 1997 and 1999 NHG guidelines (first and second revisions) [11, 12] also proposed that persons with systolic blood pressure levels of 180 mmHg or higher were eligible for drug treatment.

The scientific evidence for elevated systolic blood pressure as a CVD risk factor, the release of the WHO criteria for management of hypertension [25] and growing interest in integrated risk factor management, were reasons for the revision of the CBO guideline on high blood pressure, which was released in 2000 [13]. In the meantime, the focus on treatment of diastolic blood pressure shifted to the systolic and on total cholesterol to the ratio of total to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. The Framingham risk tables were introduced as a first step towards multifactorial risk management [26]. Risk assessment was based on age, sex, smoking status, systolic blood pressure, total/HDL cholesterol ratio and diabetes. Classification of those at high risk was based on a combination of elevated levels of systolic blood pressure with a high absolute risk of CVD, and on elevated serum cholesterol levels with a high absolute risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). A positive family history of CVD below age 60 was an additional risk factor and a reason to start drug treatment at a lower level of risk. The following stepwise approach for treatment of patients with an absolute risk of CVD ≥20% or hypertension (≥180 mmHg) was recommended: 1) diuretics (thiazides), 2) beta-blockers, 3) renin-angiotension system inhibitors. The first choice for diuretics was based on the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack trial [27]. In elderly people, diuretics are most effective, with less adverse effects. The 2003 NHG guideline (third revision) [14] was based on the 2000 CBO/NHS guideline [13].

Guidelines on high cholesterol 1987–1999

The first guidelines on serum total cholesterol were characterised by a unifactorial approach. Important evidence on the relationship between serum cholesterol and CHD mortality came from the 350,000 screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial [28]. This study showed that this relationship was strong and graded. Soon thereafter, the results of the Lipid Research Clinic Trial were published on the effect of the first generation of cholesterol-lowering drugs, the bile acid sequestrant resins [29]. This trial showed a mean decrease of 8% in serum total cholesterol and 12% in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol resulting in a 19% reduction in the incidence of CHD. These results formed the basis of the first consensus report on cholesterol in the Netherlands, published in 1987 [5]. Total cholesterol levels of at least 6.5 mmol/l were considered elevated and levels of ≥8 mmol/l strongly elevated. The cornerstone of treatment of high cholesterol levels was a healthy diet. Cholesterol-lowering medication could be considered, but prescription was restricted mainly to those with strongly elevated cholesterol levels.

Anticipating the introduction of statins, a new generation of cholesterol synthesis inhibitors, the Health Council performed a cost-effectiveness analysis in 1990 [3]. Costs per life-year gained were higher for cholestyramin than for simvastatin, and costs for both drugs were much higher than those of a cholesterol-lowering diet. The Health Council advice and the NHG 1991 guideline [7] used the same cut-off points for elevated serum cholesterol levels as recommended by the 1991 first revision of the CBO cholesterol consensus (≥8 mmol/l) [15]. Additionally, for the first time their advice on prescription of cholesterol-lowering medication depended not only on these elevated serum cholesterol levels, but also on the presence of at least one additional risk factor. Statins (simvastatin and pravastatin) became the first choice of drugs for patients with cholesterol levels above 8 mmol/l. For those with lower cholesterol levels the bile acid sequestrant resins remained first choice. At that time, it was demonstrated that statins lowered LDL-cholesterol levels by 25–35%, and could induce regression of atherosclerosis [30]. However, evidence on the effect on CHD incidence and all-cause mortality had still to be obtained.

In the mid-1990s results of important milestone studies on cholesterol treatment were published: 4S, CARE, WOSCOPS, LIPID and AFCAPS trials [31–33]. These trials showed that statins reduced CHD incidence by 25–35%. This led to revision of the CBO cholesterol consensus in 1998 [16]. The Framingham risk tables predicting 10-year CHD risk were used to identify high-risk persons. These tables were derived from the ones used by the European Societies of Cardiology, Atherosclerosis and Hypertension [34, 35]. Risk prediction was based on age, sex, smoking status, total/HDL cholesterol ratio, diabetes and hypertension. Indication for drug treatment of hypercholesterolaemia was no longer based on serum cholesterol levels alone, but also on age-specific risk scores. Age-specific cut-off points for drug treatment were formulated, based on cost-effectiveness analyses. The cut-off point of 10-year CHD incidence increased from > 25% at age 40 to 35–40% at age 70. In case of a positive family history of CHD at age <60, medication could already be prescribed at a 5% lower cut-off point of CHD risk. The first choice of drugs were statins. The first revision of the NHG guideline, published in 1999 [17], was based on the 1998 CBO consensus [16].

In 2000, the Health Council advised the Minister of Health on the indications for cholesterol treatment with statins [18]. The Council recommended to use a ‘risk score of 8’ as cut-off point for treatment with statins. This means that persons with a total/HDL cholesterol ratio higher than 8, or those with a ratio higher than 7 plus one additional risk factor, or a ratio of 6 with two additional risk factors (e.g. smoking and hypertension) qualified for statin treatment. The major reason not to recommend risk tables was that the Council preferred a simplified method to select high-risk persons, without the need to consult tables. Only a minority of the committee was in favour of considering costs for determining indications for cholesterol-lowering therapy. The ‘risk score of 8’ did not become common clinical practice.

Guidelines on cardiovascular risk management 2006–2011

In the first decade of the 21st century, the shift from unifactorial to multifactorial risk factor management was completed. In 2003, the results of the first large trial on the effects of a powerful new statin, atorvastatin, were published [36]. This statin was tested in persons with hypertension, average or below average serum cholesterol levels, and at least three additional risk factors. Atorvastatin treatment reduced major cardiovascular events by 35%, major cerebrovascular events by 48% and all-cause mortality by 15%. In 2006, the CBO and NHG released the first ‘Multidisciplinary Guideline on CardioVascular Risk Management in clinical practice’ [9]. In line with the European guideline on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice [37, 38], the earlier used US Framingham risk tables were replaced by those of the European based Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) system (box 1) [37]. The SCORE group adapted the risk function for the Netherlands. The risk factors in the SCORE tables were the same as those in the Framingham risk tables, except for diabetes.

The introduction of the SCORE risk charts meant a change from predicting 10-year risk of CHD incidence to 10-year risk of CVD mortality. The cut-off point for identifying those who needed drug treatment for elevated blood pressure and cholesterol was a 10-year CVD mortality risk of ≥10% [9]. This was higher than the cut-off point used in the European guidelines (≥5%) [38, 39]. This higher cut-off point was based on a cost-effectiveness analysis and on preventing an increase in the work load of general practitioners. At a risk between 5% and 10%, drug treatment could be started when additional risk factors—such as clinical signs of organ damage, a positive family history of CVD <60 years, a BMI >30 kg/m2 or a waist circumference >88 cm for women and >102 cm for men—were present. Based on cost-effectiveness, drug treatment of elevated blood pressure was started with a low dose of a diuretic and, if the targets were not reached, other classes of antihypertensive drugs could be added. Treatment of elevated serum cholesterol started with simvastatin and pravastatin. When the targets were not reached, atorvastatin was not recommended for those without CVD or type II diabetes, because of the limited evidence for an effect on CVD endpoints and on safety.

After the 2006 guideline on Cardiovascular Risk Management, results on the effectiveness of drug treatment of blood pressure and serum cholesterol cumulated exponentially, and several meta-analyses were published. The effectiveness of blood pressure-lowering drugs in the prevention of CVD was demonstrated in 27 randomised clinical trials in more than 100,000 persons with no history of CHD, all classes of antihypertensive drugs showed similar effects in reducing CVD events [40]. The benefit of statin therapy in about 70,000 persons without CVD was investigated in a meta-analysis including trials with the first generations of statins: simvastatin (HPS), lovastatin (AFCAPS/TexCAPS) and pravastatin (WOSCOPS, PROSPER, ALLHATT-LTT, MEGA), and with the more recently developed statins, atorvastatin (ASCOT-LLA, CARDS, ASPEN) and rosuvastatin (JUPITER) [41]. Major coronary events were reduced by 30%, major cerebrovascular events by 19%, and all-cause mortality by 12%. However, CHD mortality was not significantly reduced.

The first revision of the multidisciplinary guideline on cardiovascular risk management was published in 2011 [19]. A shift was made from risk tables with CVD mortality to total CVD incidence. The nonfatal endpoints included were myocardial infarction, stroke and heart failure. This also meant a shift in cut-off points for high risk to ≥20%, for intermediate risk to 10–20%, and for low risk to <10%. For those at intermediate risk, one strongly and two or more moderately elevated CVD risk factors can be an indication for drug treatment. Among the strongly elevated risk factors were having at least two family members with a history of CVD below the age of 65 or at least one with a history of CVD below age 60, BMI > 35 kg/m2 and a sedentary lifestyle. The mildly elevated risk factors included having one family member with a history of CVD below age 65, BMI 30–35 kg/m2 and less than 30 min physical activity on five or less days a week. Also diminished kidney function is considered an additional risk factor. For treatment of elevated blood pressure levels, all classes of drugs can be used, with a mild preference for diuretics in those without CVD. A stepwise approach was recommended. Based on cost-effectiveness, drug treatment of elevated serum cholesterol levels started with simvastatin. If the treatment goal of LDL ≤2.5 mmol/l is not reached, a switch to rosuvastatin, or atorvastatin is recommended.

Conclusion

Cardiovascular risk management has changed over the past 30 years from unifactorial treatment of severe hypertension (diastolic blood pressure ≥115 mmHg) and severe hypercholesterolaemia (≥8 mmol/l), to multifactorial risk factor treatment based on overall cardiovascular risk and treatment of elevated systolic blood pressure and/or serum total and HDL cholesterol levels. Nowadays, the concept that ‘the lower the risk factors, the lower the absolute risk’ is the leading paradigm in CVD prevention.

Box 1

SCORE risk charts

Risk charts of the SCORE (Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation) project were derived from a large database of prospective studies including over 200,000 persons in Europe. Risk equations for high-risk countries were based on data collected in cohorts from Denmark, Finland and Norway and for low-risk countries from Belgium, Italy and Spain [37]. Almost all participants in these cohorts were recruited in the 1970s and early 1980s. At the time of construction of these SCORE charts, the Netherlands was considered a high-risk country. The SCORE group adapted the risk function for the Netherlands, using the national percentage of smokers and average systolic blood pressure and serum total and HDL-cholesterol levels derived from a Dutch survey carried out between 1998 and 2001 (Regenboog project; RIVM) and using national CVD mortality statistics from 2000 (WHO mortality database).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Drs. A. van Drenth (NHS) and Dr. Tj. Wierdsma for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation.

References

- 1.Interim advice on hypertension. Health Council, The Hague, 1978/18.

- 2.Advice on hypertension. Health Council, The Hague, 1983/2.

- 3.Cholesterol. Health Council, The Hague, 1990/1.

- 4.Consensus diagnostics and treatment of hypertension. Hart Bulletin 1990;21:142–210.

- 5.Cholesterol consensus. Hart Bulletin supplement 1987;1:3–64.

- 6.Binsbergen JJ, Grundmeyer HGLM, Hoogen JPH, et al. NHG-Guideline on hypertension. Huisarts Wet. 1991;34:389–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binsbergen JJ, Brouwer A, Drenth BB, et al. NHG-Guideline on cholesterol. Hart Bulletin supplement. 1992;23:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Multidisciplinary guideline on cardiovascular risk management. CBO/NHG, Utrecht 2006.

- 9.Smulders YM, Burgers JS, Scheltens T, et al. Clinical practice guideline for cardiovascular risk management in the Netherlands. Neth J Med. 2008;66:169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NHG-Guideline on cardiovascular risk management (M84). nhg.artsennet.nl. 2006.

- 11.Walma EP, Grundmeyer HGLM, Thomas S, et al. NHG-Guideline on hypertension M17 (first revision) Huisarts Wet. 1997;40:598–617. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walma EP, Grundmeijer HGLM, Thomas S, et al. NHG-Guideline on hypertension (second revision 1999) In: Geijer RMM, Burgers JS, Laan JR, Wiersma T, Rosmalen DFH, Thomas S, et al., editors. NHG-Guidelines for general practitioners part I. Maarssen: Elsevier/Bunge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revision of guideline high blood pressure. CBO/NHF, Utrecht/The Hague, 2000.

- 14.Walma EP, Thomas S, Prins A, et al. NHG-Guideline on hypertension (M17) (third revision) Huisarts Wet. 2003;46:435–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revision consensus cholesterol. Hart Bulletin supplement 1992;23:2–26.

- 16.Consensus cholesterol, second revision. Hart Bulletin 1998;29:112–131.

- 17.Thomas S, Weijden T, Drenth BB, et al. NHG-Guideline on cholesterol M20 (first revision) Huisarts Wet. 1999;42:406–17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cholesterol lowering therapy. Health Council, The Hague, 2000/17.

- 19.Multidisciplinary guideline on cardiovascular risk management (revision). NHG, Utrecht, 2011. [PubMed]

- 20.Hypertension detection and follow-up program cooperative group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. JAMA 1979;242:2562–77. [PubMed]

- 21.Report by the management committee. The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Lancet 1980;i:1261–7. [PubMed]

- 22.Treating mild hypertension:agreement from the large trials. Report of the British Hypertension Society working party. BMJ 1989;298:694–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.MacMahon S, Rodgers A. The effects of blood pressure reduction in older patients: an overview of five randomized controlled trials in elderly hypertensives. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1993;15:967–78. doi: 10.3109/10641969309037085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulrow CD, Cornell JA, Herrera CR, et al. Hypertension in the elderly. Implications and generalizability of randomized trials (review) JAMA. 1994;272:1932–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520240060042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalmers J, MacMahon S, Mancia G, et al. World Health organization-international society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. Guidelines sub-committee of the world health organization. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1999;21:1009–60. doi: 10.3109/10641969909061028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Odell PM, et al. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991;83:356–62. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.83.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic. JAMA 2002;288:2981–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Stamler J, Wentworth D, Neaton JD. Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) JAMA. 1986;256:2823–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03380200061022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial results. I. Reduction in incidence of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1984;251:351–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Jukema JW, Bruschke A, Boven AJ, et al. Effects of lipid lowering by pravastatin on progression and regression of coronary artery disease in symptomatic men with normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol levels. The Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS) Circulation. 1995;91:2528–40. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.91.10.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383–9. [PubMed]

- 32.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1301–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sacks FM, Pastemak RC, Gibson CM, et al. Effect on coronary atherosclerosis of decrease in plasma cholesterol concentrations in normocholesterolaemic patients. Lancet. 1994;344:1182–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyörälä K, Backer G, Graham I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:1300–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood D, Backer G, Faergeman O, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the second joint task force of european and other societies on coronary prevention. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:1434–503. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1149–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third joint task force of European and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003;10:S1–10. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: full text. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(Suppl 2):S1–113. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000277983.23934.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE, et al. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338:b2376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]