Abstract

Synthetic lethal therapeutic strategy using poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor Olaparib in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation has shown promise in clinical settings. Since < 5% of patients are BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers, small molecules that functionally mimic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations will extend the synthetic lethal therapeutic option for non-mutation carriers. Here we provide proof of principle for this strategy using a BRCA1 inhibitor peptide 2 that targets the BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interaction and mimics the M177R/K BRCA1 mutation. Reciprocal immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of BRCA1 and Abraxas was used to demonstrate inhibitor 2 targets BRCT(BRCA1)-Abraxas interface. Immunostaining of γH2AX, cell cycle analysis and homologous recombination (HR) assays were conducted to confirm that inhibitor 2 functionally mimics a chemosensitizing BRCA1 mutation. The concept of synthetic lethal therapeutic strategy with the BRCA1 inhibitor 2 and the PARP inhibitor Olaparib was explored in HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and HCC1937 cell lines. The results show that inhibition of BRCA1 by 2 sensitizes HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells but not HCC1937 to Olaparib mediated growth inhibition and apoptosis. These results provide the basis for developing high affinity BRCT(BRCA1) inhibitors as adjuvants to treat sporadic breast and ovarian cancers.

Keywords: Synthetic lethal therapeutic strategy, BRCA1 inhibitor, Abraxas, Chemosensitization, Olaparib, IR

Introduction

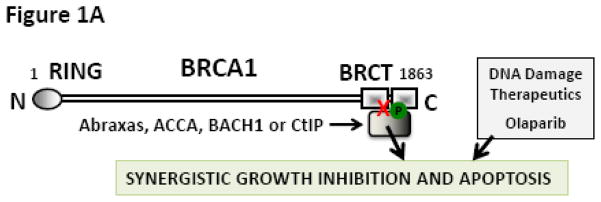

Synthetic lethal therapeutic strategy exploits a condition in which cells can live with either 1 of 2 pathways but not without both. Among others the cells require functional PARP to repair single-strand breaks and functional BRCA to repair double-strand breaks. Cells will survive if either PARP or BRCA is disabled. However, they will die if both pathways are disabled. This observation has been effectively translated to the clinical setting where BRCA mutation carriers responded well to PARP inhibitors [1]. Since >95% of breast and ovarian cancer patients carry the wild type BRCA, we hypothesized that small molecule inhibitors that functionally mimic chemosensitizing BRCA mutations will facilitate the extension of the synthetic lethal therapeutic option (Fig. 1A) to the larger patient population.

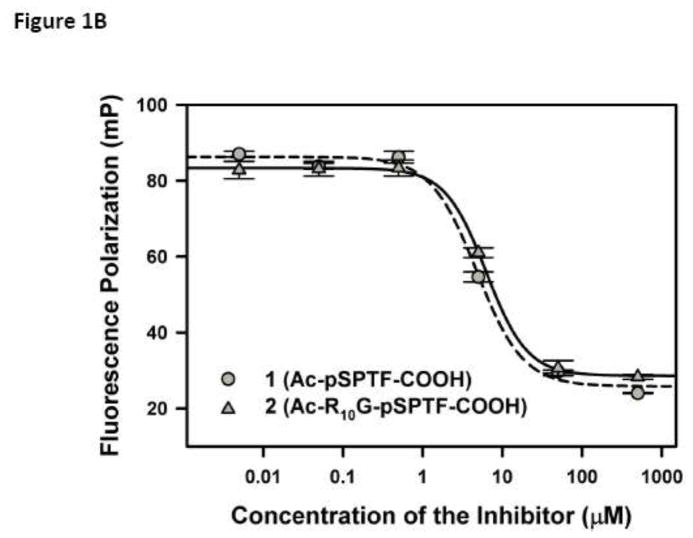

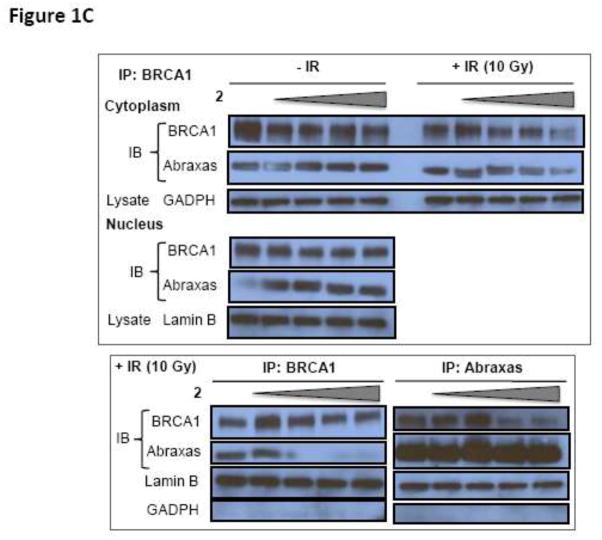

Fig. 1.

(A) Proposed hypothesis: Small molecule inhibitors of BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interaction will increase the sensitivity of cancer cells to DNA damage based therapeutics. The inhibitor is represented as a red X. (B) Competitive inhibition curves for BRCT(BRCA1) inhibitor peptides 1 (Ac-pSPTF-CO2H) and 2 (Ac-R10G-pSPTF-CO2H). (C) Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Immunoblotting (IB) studies with and without the BRCT inhibitor 2 in the presence and absence of IR-induced DNA damage.

Towards this goal, using a variety of biophysical techniques we reported the identification of a nanomolar BRCA1 binding tetrapeptide 1 [2,3]. Structural studies show that the tetrapeptide binds to the phosphoprotein (Abraxas/BACH1/CtIP) binding site on the carboxy terminal domains of BRCA1 (BRCT) and mimics the M1775R/K BRCA1 mutant [4,5]. This is a proof of principle study. Here we demonstrate that in cells inhibition of BRCA1 and treatment with PARP inhibitors leads to synthetic lethality. For this study we used a BRCT(BRCA1) inhibitor peptide 2, which is a cell permeable version of 1. We characterize inhibitor 2 in a panel of cellular assays to show that 2 (i) inhibits Abraxas binding to BRCT(BRCA1); (ii) inhibits homologous recombination (HR); (iii) sensitizes cells to IR-induced DNA damage; (iv) releases IR-induced G2/M arrest and (v) sensitizes wild-type BRCA1 containing cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and HeLa) to PARP inhibitor (Olaparib) but not a truncated BRCA1 containing cell line (HCC1937). The results suggest the Abraxas/BACH1/CtIP binding site on BRCT(BRCA1) is a potential target for therapeutic development. High affinity BRCT(BRCA1) inhibitors will facilitate the extension of the synthetic lethal therapeutic option to all breast cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

The cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD). MCF7 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum. HCC1937 cells and HeLa cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were maintained in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. Details for the treatment of cells, preparation of cell lysate, immunoprecipitation, Western blotting and immunofluorescence can be found in the supplementary material.

Flow cytometric analysis of Cell cycle

MCF7 cells in log phase treated with and without 100 μM peptide 2 along with or without IR (at 15 Gy). The cells were incubated for 24 h, harvested and washed in PBS. Cells then were fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol, stained with propidium iodide (PI) and analyzed for DNA content using FACSCalibur (Beckon Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Homologous recombination assay

U2OS-DR cells with an integrated reporter construct for HR-mediated repair of GFP and pCBASce plasmid were kindly provided by Drs. Maria Jasin and Koji Nakanishi (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). U2OS-DR cells [6] were seeded at 2 × 105 per well and incubated overnight in a 6-well plate. Transfection of 4 μg of an I-SceI expression vector pCBASce [7] or an empty vector was performed with 10 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). After 4 h of incubation, the transfection mixture was removed and the cells were incubated for 2 h in a medium with 100 μM peptide 2. The medium with the peptide was removed and the cells were incubated in a fresh medium for additional 48 h. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was quantitated by flow cytometric analysis. Results were the average of data obtained from three or four independent experiments.

Cell viability assay and caspase 3/7 activity assay

Cells were seeded in clear bottom white 96-well plates at a density of 2500 cells/well and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were then treated with the indicated compounds and assayed for viability over 3-days using AlamarBlue (Ab Serotec). At indicated time points, 10% of AlamarBlue reagent was added to the cells and incubated for an additional 3h. Fluorescence was measured using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Inc.) at ex/em 544/590 nm. Cells were also assayed for apoptosis using Caspase 3/7 activity using the caspase-Glo reagent (Promega Corp) after a 48 h-incubation. Luminescence was measured and data was normalized for cell number using AlamarBlue.

Data processing and statistical analysis

P-values were determined using one way ANOVA in SigmaPlot and values < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Inhibitor 1 and 2 inhibit BRCT(BRCA1) - FITC- βA-pSPTF binding

Inhibitor tetrapeptide 1 (Ac-pSPTF-CO2H) and inhibitor 2 (Ac-R10G-pSPTF-CO2H) were titrated into a mixture of BRCT(BRCA1) and FITC-βA-pSPTF (4 μM and 0.1 μM), incubated for 15 min and fluorescence polarization was measured. The Ki values determined through curve fitting the data are 1 = 0.23 ± 0.06 M and 2 = 0.40 ± 0.07 M (Fig. 1B).

Inhibitor 2 inhibits BRCA1 – Abraxas interaction

HeLa cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, 50 100 μM) of inhibitor 2 in the presence or absence of IR (10 Gy). The cells were lysed, the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were separated and subjected to reciprocal immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB) with BRCA1 and Abraxas antibodies (Fig. 1C). The bottom panel shows reciprocal IP and IB with BRCA1 and Abraxas antibodies of nuclear fractions subjected to IR with increasing concentrations of 2. Western blot analyses showed that inhibitor 2 had no effect on BRCA1 – Abraxas interaction in the cytoplasm in the presence or absence of IR and in the nucleus in the absence of IR (Fig. 1C). However, in IR-treated nuclear fractions, inhibition of BRCA1 – Abraxas interaction by 2 was observed (Fig. 1C).

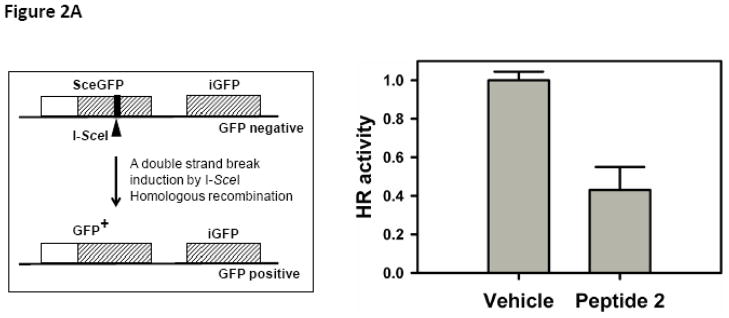

Inhibitor 2 attenuates HR

U2OS-DR cells with an integrated reporter construct for HR-mediated repair of GFP were subjected to inhibitor 2 [6,7]. The HR mediated repair was measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 2A). We observed a ~40% reduction in the HR activity in the presence of inhibitor 2.

Fig. 2.

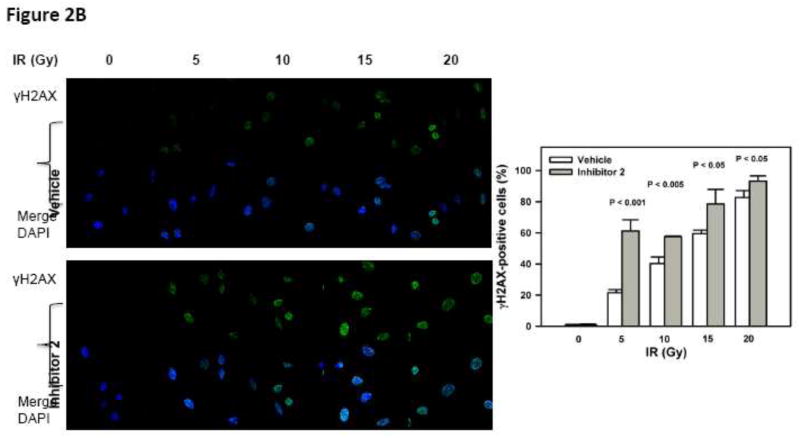

(A) Left Cell-based double strand break repair assay. Right U2OS-DR cells with an integrated reporter construct for HR-mediated repair of GFP was subjected to inhibitor 2. (B) Inhibition of BRCT(BRCA1) by inhibitor 2 sensitizes cells to DNA damage. DNA damage was induced by increasing doses of IR in the presence (10 μM) and absence of inhibitor 2. DNA damage was assessed by γH2AX staining and DAPI was used to stain the nucleus. The bar chart on the right shows quantification.

Inhibitor 2 sensitizes cells to IR induced DNA damage

HeLa cells were subjected to increasing doses of IR (0 – 20 Gy) in the presence or absence of 2. After 30 min, the cells were fixed and stained for γH2AX, which is a biochemical marker for DNA damage (Fig. 2B). We observed that inhibitor 2 by itself did not result in any detectable DNA damage by γH2AX staining as compared to vehicle treated cells. However, cells treated with IR and inhibitor 2 show stronger staining with γH2AX antibody. Cells positive to γH2AX staining were counted and the percentage of cells are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

DNA damage measured by γH2AX staining of cells

| IR (Gy) | Cells positive to γH2AX staining (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Control | Inhibitor 2 | |

| 0 | 0.36 ± 0.52 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 5 | 11.03 ± 0.20 | 35.72 ± 2.78 |

| 10 | 29.02 ± 2.65 | 47.13 ± 9.85 |

| 15 | 55.48 ± 2.79 | 81.55 ± 3.93 |

| 20 | 68.51 ± 6.00 | 85.46 ± 3.65 |

Inhibitor 2 releases IR induced G2/M arrest

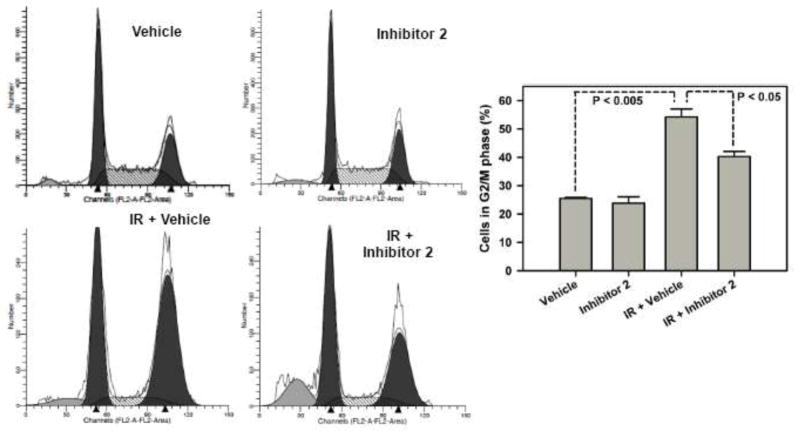

MCF7 cells were treated with and without IR and/or inhibitor 2 (100 μM) (Fig. 3). Mock cells have about 25.5 ± 0.318 % cells in G2/M phase. When treated with inhibitor 2, cells show a similar percentage of 23.9 ± 2.23 % in G2/M phase. Cells accumulated in the G2/M phase in response to IR (54.8 ± 2.79 %). Cells treated with both IR and 2 showed fewer cells accumulated in the G2/M phase (40.3 ± 1.80 %) when compared to IR alone treated cells

Fig. 3.

BRCT(BRCA1) inhibitor 2 releases IR induced G2/M arrest. The cells were subjected to the inhibitor (100 μM) in the presence and or absence of IR (15 Gy). After 24 h the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Inhibitor 2 sensitizes cells carrying wild-type BRCA1 to PARP inhibitor Olaparib

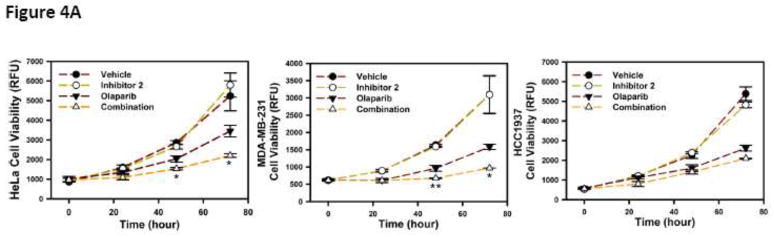

HeLa, MDA-MB-231 and HCC1937 cells were treated with 50 μM inhibitor 2, 25 μM Olaparib and the combination and cell growth was monitored over time (Fig. 4A). We observed a synergistic inhibition of growth in HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells but not in HCC1937 cells.

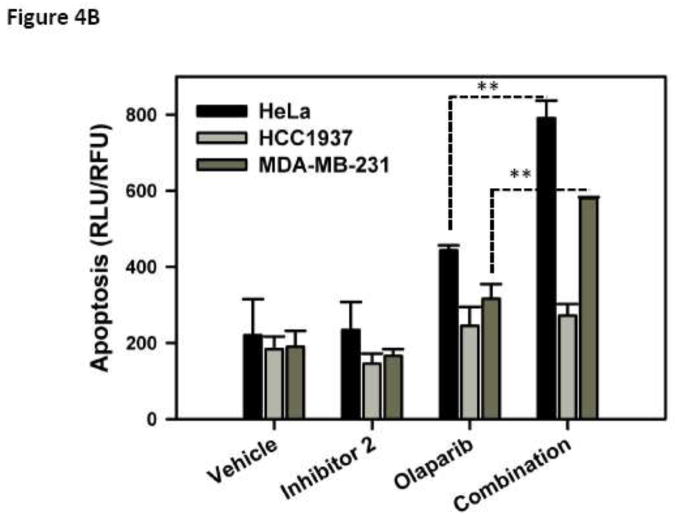

Fig. 4.

(A) Viability of cells with wild type BRCA1 (HeLa and MDA-MB-231) and truncated BRCA1 (HCC1937) in the presence of inhibitor 2, Olaparib (PARP inhibitor) and the combination was determined. (B) Induction of apoptosis was measured in a Caspase 3/7 assay. Cells were treated with inhibitor 2 at 50 μM, Olaparib at 25 μM and combination at these concentrations for 48 h and caspase 3/7 activity was measured. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.005

HeLa, MDA-MB-231 and HCC1937 were treated with 50 μM inhibitor 2, 25 μM Olaparib and the combination. Caspase 3/7 activity was used as a measure of apoptosis in these cells. We observe a synergistic effect in HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells and not in HCC1937 cells in the apoptosis study (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

BRCT(BRCA1) domains are phosphoprotein binding modules and tetrapeptides pSXXF are the minimal unit required for BRCT(BRCA1) binding [2–5,8,9]. We conducted a systematic structure activity relationship study and reported the identification of a tetrapeptide 1 (Ac-pSPTF-CO2H) with nanomolar binding affinities for BRCT(BRCA1) [3]. Attempts to use peptide 1 for cellular studies failed due to permeability issues associated with negative charges on the phosphate group and the carboxylate at physiological pH. The use of a poly-arginine tag to deliver cargo into cells is a well-accepted strategy [10]. Therefore, we generated inhibitor 2 (Ac-R10G-pSPTF-CO2H) which has a poly-arginine sequence tagged to the N-terminus of peptide 1. Competitive fluorescence polarization studies with BRCT(BRCA1) showed that both 1 and 2 had equivalent Ki values. This indicates that the tag (R10G-) on inhibitor 2 does not affect binding to BRCT(BRCA1) (Fig. 1B) [11,12].

To determine if inhibitor 2 targets the BRCT(BRCA1) in a cellular system, we carried out reciprocal IP and IB studies using BRCA1 and Abraxas antibodies. Western blot analyses showed that inhibitor 2 only affects BRCA1 – Abraxas interaction, in the nuclear fractions and in the presence of IR. This demonstrates the selectivity of inhibitor 2 for the BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interface. This suggests inhibition of the BRCT(BRCA1) domains by inhibitor 2.

A recombinant substrate DR-GFP was used in a cell-based double strand break (DSB) repair assay.[13] DR-GFP is composed to two inactive alleles of GFP gene in a single locus in the genome. One of the GFP genes, SceGFP, is mutated to contain the recognition site for the rare-cutting I-SceI endonuclease. These substituted base pairs also generate two in-frame stop codons. Downstream of SceGFP gene is the 812-bp internal GFP fragment (iGFP), which also does not produce an intact GFP. A DSB is introduced in SceGFP gene by expressing I-SceI by transient expression. iGFP gene acts as a donor of homologous sequence to the broken SceGFP gene. A successful homologous recombination event results in the expression of intact GFP protein and GFP positive cells are quantified by flowcytometry (Figure 2A left).

Genetic knock down of BRCA1 results in partial inhibition (~60%) of HR [14]. To determine the effect of inhibitor 2 on HR we conducted the same experiment with and without 2 [6]. The observation of a ~40% reduction in the HR activity in the presence of 2 suggests that inhibitor 2 blocks HR activity by binding to the BRCT(BRCA1) and functionally mimics the genetic studies (Fig. 2A). Since inhibitor 2 perturbs HR, we speculated that inhibitor 2 will sensitize cells to IR induced DNA damage. Indeed we observe a synergistic increase in the γH2AX foci in cells treated with the inhibitor 2 and IR when compared to individual treatments (Table 1 and Figure 2B). Together, these results suggest that inhibitor 2 sensitizes cells to DNA damage by binding to BRCT(BRCA1) and blocking HR.

Knock down studies of the BRCT(BRCA1) and its binding partners using siRNA established that the BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interactions regulate G2/M checkpoints in response to DNA damage [9,15–18]. This led us to hypothesize that inhibition of BRCT(BRCA1) by inhibitor 2 in response to DNA damage will result in G2/M checkpoint dysfunction. As expected, cells accumulated in the G2/M phase in response to IR [19] and pretreatment with inhibitor 2 followed by IR showed a smaller percentage of cells in G2/M phase. This suggests that inhibition of BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interactions by 2 results in the release of the IR induced G2/M accumulation. Together these studies suggest that inhibitor 2 treated cells functionally mimic BRCA1 knock down.

The use of PARP inhibitors in BRCA mutation carriers has received a lot of attention in recent years [20,21]. Since inhibitor 2 treated cells behave like BRCA1 knock down cells, we hypothesized that inhibitor 2 will sensitize cells carrying wild-type BRCA1 to PARP inhibitors. We opted to use Olaparib a PARP inhibitor [22] that is in clinical trials to evaluate synergistic growth inhibition and apoptosis with 2. We observed no growth inhibitory effects in cells treated with increasing concentrations up to 100 μM of 2 (data not shown). We also observed precipitation of Olaparib at higher than 25 μM concentrations. Therefore, we subjected HeLa, MDA-MB-231 and HCC1937 cells with 50 μM inhibitor 2, 25 μM Olaparib and the combination and cell growth was monitored over time (Fig. 4A). Since inhibitor 2 does not inhibit cell growth by itself we are unable to determine the combination index for this study. The observation of a synergistic inhibition of growth in HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells but not in HCC1937 cells is consistent with our observations in the functional assays as HCC1937 cells have a truncated BRCA1 and inhibitor 2 will have no effect.

To explore if the synergistic effects extends to the induction of apoptosis we carried out an experiment using caspase 3/7 activity as a read out for apoptosis. Only HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells showed synergistic effects in the apoptosis study (Fig. 4B). Together our results provide proof of concept that targeting BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interface is a viable synthetic lethality therapeutic strategy. The cell-based studies were carried out with micromolar concentration of inhibitor 2. The micromolar concentrations were necessary because it is well known that peptides are easily degraded and have short half-lives. These studies highlight the need for high affinity binders of BRCT(BRCA1) that are stable in a cellular matrix with longer half-lives [23]. We are currently working to address this issue and results from these studies will be reported in due course.

Synthetic lethality has been effectively exploited to treat BRCA mutation carriers with PARP inhibitors. Results from the studies presented here indicate that small molecule inhibitors of the BRCT(BRCA1)-phosphoprotein interface will enable the extension of this therapeutic strategy to non-BRCA mutation carriers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01CA127239. We thank the UNMC flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning microscopy core facilities.

Table of abbreviations

- PARR

poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- IB

immunoblotting

- HR

homologous recombination

- IR

Ionizing Radiation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest

Contributor Information

Ziyan Yuan Pessetto, Email: zyuan@kumc.edu, Eppley Institute for Cancer Research, University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha NE 68198.

Ying Yan, Eppley Institute for Cancer Research, University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha NE 68198, (402) 559-3036.

Tadayoshi Bessho, Eppley Institute for Cancer Research, University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha NE 68198, (402) 559-7018.

Amarnath Natarajan, Email: anatarajan@unmc.edu, Eppley Institute for Cancer Research, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Genetics Cell Biology and Anatomy, University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha NE 68198, Telephone: (402) 559 3793, Fax number: (402) 559 8270.

References

- 1.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, Mortimer P, Swaisland H, Lau A, O’Connor MJ, Ashworth A, Carmichael J, Kaye SB, Schellens JH, de Bono JS. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361 (2):123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lokesh GL, Muralidhara BK, Negi SS, Natarajan A. Thermodynamics of phosphopeptide tethering to BRCT: the structural minima for inhibitor design. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129 (35):10658–10659. doi: 10.1021/ja0739178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan Z, Kumar EA, Kizhake S, Natarajan A. Structure-activity relationship studies to probe the phosphoprotein binding site on the carboxy terminal domains of the breast cancer susceptibility gene 1. J Med Chem. 2011;54 (12):4264–4268. doi: 10.1021/jm1016413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell SJ, Edwards RA, Glover JN. Comparison of the structures and peptide binding specificities of the BRCT domains of MDC1 and BRCA1. Structure. 2010;18 (2):167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph PR, Yuan Z, Kumar EA, Lokesh GL, Kizhake S, Rajarathnam K, Natarajan A. Structural characterization of BRCT-tetrapeptide binding interactions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393 (2):207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakanishi K, Yang YG, Pierce AJ, Taniguchi T, Digweed M, D’Andrea AD, Wang ZQ, Jasin M. Human Fanconi anemia monoubiquitination pathway promotes homologous DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102 (4):1110–1115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407796102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson C, Elliott B, Jasin M. Chromosomal double-strand breaks introduced in mammalian cells by expression of I-Sce I endonuclease. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;113:453–463. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-675-4:453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manke IA, Lowery DM, Nguyen A, Yaffe MB. BRCT repeats as phosphopeptide-binding modules involved in protein targeting. Science. 2003;302 (5645):636–639. doi: 10.1126/science.1088877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu X, Chini CC, He M, Mer G, Chen J. The BRCT domain is a phospho-protein binding domain. Science. 2003;302 (5645):639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1088753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wender PA, Mitchell DJ, Pattabiraman K, Pelkey ET, Steinman L, Rothbard JB. The design, synthesis, and evaluation of molecules that enable or enhance cellular uptake: peptoid molecular transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97 (24):13003–13008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lokesh GL, Rachamallu A, Kumar GD, Natarajan A. High-throughput fluorescence polarization assay to identify small molecule inhibitors of BRCT domains of breast cancer gene 1. Anal Biochem. 2006;352 (1):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Jadhav A, Lokesh GL, Klumpp C, Michael S, Austin CP, Natarajan A, Inglese J. Dual-fluorophore quantitative high-throughput screen for inhibitors of BRCT-phosphoprotein interaction. Anal Biochem. 2008;375 (1):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce AJ, Hu P, Han M, Ellis N, Jasin M. Ku DNA end-binding protein modulates homologous repair of double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15 (24):3237–3242. doi: 10.1101/gad.946401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Scully R, Sobhian B, Xie A, Shestakova E, Livingston DM. RAP80-directed tuning of BRCA1 homologous recombination function at ionizing radiation-induced nuclear foci. Genes Dev. 2011;25 (7):685–700. doi: 10.1101/gad.2011011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu X, Chen J. DNA damage-induced cell cycle checkpoint control requires CtIP, a phosphorylation-dependent binding partner of BRCA1 C-terminal domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24 (21):9478–9486. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9478-9486.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobhian B, Shao G, Lilli DR, Culhane AC, Moreau LA, Xia B, Livingston DM, Greenberg RA. RAP80 targets BRCA1 to specific ubiquitin structures at DNA damage sites. Science. 2007;316 (5828):1198–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1139516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B, Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Zhang D, Smogorzewska A, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316 (5828):1194–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1139476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H, Chen J, Yu X. Ubiquitin-binding protein RAP80 mediates BRCA1-dependent DNA damage response. Science. 2007;316 (5828):1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1139621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu B, Kim ST, Lim DS, Kastan MB. Two molecularly distinct G(2)/M checkpoints are induced by ionizing irradiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22 (4):1049–1059. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1049-1059.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC, Ashworth A. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434 (7035):917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Underhill C, Toulmonde M, Bonnefoi H. A review of PARP inhibitors: from bench to bedside. Ann Oncol. 2011;22 (2):268–279. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narod SA. BRCA mutations in the management of breast cancer: the state of the art. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7 (12):702–707. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan Z, Kumar EA, Campbell SJ, Palermo NY, Kizhake S, Glover JNM, Natarajan A. Exploiting the P-1 pocket of BRCT domains towards a structure guided inhibitor design. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2 (10):764–767. doi: 10.1021/ml200147a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.