Abstract

Dysfunction of the heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein TAR DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43) is associated with neurodegeneration in diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). Here we examine the effects of a series of 4-aminoquinolines with affinity for TDP-43 upon caspase-7-induced cleavage of TDP-43 and TDP-43 cellular function. These compounds were mixed inhibitors of biotinylated TG6 binding to TDP-43, binding to both free and occupied TDP-43. Incubation of TDP-43 and caspase-7 in the presence of these compounds stimulated caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43. This effect was antagonized by the oligonucleotide TG12, prevented by denaturing TDP-43, and exhibited a similar relation of structure to function as for the displacement of bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43. In addition, the compounds did not affect caspase-7 enzyme activity. In human neuroglioma H4 cells, these compounds lowered levels of TDP-43 and increased TDP-43 C-terminal fragments via a caspase-dependent mechanism. Subsequent experiments demonstrated that this was due to induction of caspases 3 and 7 leading to increased PARP cleavage in H4 cells with similar rank order of the potency among the compounds tests for displacement of bt-TG6 binding. Exposure to these compounds also reduced HDAC6, ATG7, and increased LC3B, consistent with the effects of TDP-43 siRNA described by other investigators. These data suggest that such compounds may be useful biochemical probes to further understand both the normal and pathological functions of TDP-43, and its cleavage and metabolism promoted by caspases.

Keywords: TDP-43, caspase activation, mixed inhibition

1.0 Introduction

Trans-activating response (TAR) DNA binding protein (TDP-43) is a nucleic acid binding protein that is expressed primarily in the nucleus and also in cytoplasmic granules, where it functions as a regulator of gene transcription and splicing as well as RNA stabilization and subcellular localization [1, 2]. The structure of TDP-43 is typical of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) with two RNA recognition motifs, designated RRM1 and RRM2, along with a glycine rich C-terminal prion-like domain which interacts with other hnRNPs to regulate gene splicing [1, 3–5]. TDP-43 was initially characterized as a transcriptional repressor of HIV-1 gene expression as well as the cause of pathological exon 9 skipping in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene [4, 6–8]. Recently, it has been shown that TDP-43 plays an important role in mRNA stabilization/degradation of certain proteins that control the cell cycle such as cyclin dependent kinase 6 (Cdk6) and the phosphor-retinoblastoma (pRb) pathway [9], as well as autophagy related protein (ATG7), and the transcriptional regulator histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) [10, 11]. In addition, TDP-43 was shown to be involved in stress granule formation where it regulates assembly and maintenance of stress granules in response to oxidative stress or heat shock [12–15]. Therefore, TDP-43 plays an important role not only in gene transcription and splicing, but also mRNA stabilization and degradation.

TDP-43 has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [1, 16–20]. Immunocytochemical studies have documented motor neuron inclusions containing phosphorylated and ubiquitinylated TDP-43 C-terminal fragments (CTFs) in ALS patients and that this aggregation is accompanied by a decrease of TDP-43 in the nucleus [16, 21–23]. However, the cause of this cytoplasmic translocation and subsequent accumulation of TDP-43 CTFs is not completely understood. One possibility is that these CTF aggregates are the result of abnormal overexpression of TDP-43 with subsequent metabolism by caspases leading to CTF aggregates [2, 24, 25]. However, it is not entirely clear whether or not toxicity is due to a gain of function resulting from high levels of TDP-43, or a loss of function due to increased metabolism with subsequent sequestration of CTF aggregates [26, 27]. Nonetheless, overexpressing wild-type TDP-43 in transgenic animals, such as Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, zebrafish and mice, leads to neurodegeneration in a dose dependent manner independent of the accumulation of CTF aggregates [25]. Moreover, transgenic mice overexpressing TDP-43 exhibit relatively selective degeneration in layer V cortical neurons and spinal motor neurons, consistent with ALS and FTLD as well as develop movement deficits such as spastic quadripelegia similar to ALS [28, 29]. Therefore, the TDP-43 CTF aggregates observed in ALS and FTLD may be the result of increased TDP-43 metabolism in order to overcome the toxicity associated with pathological overexpression TDP-43.

In cell culture models, both overexpression of TDP-43 as well as RNAi knockdown result in cytotoxicity suggesting that the levels of TDP-43 are tightly regulated [9, 30]. Activation of caspases via apoptotic pathways results in the metabolism of TDP-43 via caspase-3 and 7 mediated cleavage at Asp89 and Asp169 resulting 35 kDa and 25 kDa TDP-43 CTFs which are then subsequently cleared by the proteosome [30–32]. A recent study using motor neuron-like NSC-34 cells demonstrated that modest overexpression of full length TDP-43 induces cytotoxicity, while overexpression of TDP-43 CTFs is relatively benign [30]. In addition, overexpression of a caspase cleavage resistant TDP-43 mutant exhibited greater toxicity than full length wild-type TDP-43 in these cells, thereby suggesting that caspase cleavage and subsequent generation of TDP-43 CTFs may be a compensatory mechanism whereby the cell attempts to attenuate toxicity associated with overexpression of full length TDP-43 [30]. We hypothesized that binding to TDP-43 might induce a conformational change and in turn effect the rate of caspase cleavage. Here, we report the characterization of a series of 4-aminoquinoline probe compounds that were discovered from high-throughput screening on caspase-mediated cleavage of TDP-43 [33]. We demonstrate that these probes are mixed inhibitors of TDP-43 and actually stimulate caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43. In addition, we describe the functional consequences of 4-aminquinoline binding to TDP-43 on cellular function as described by siRNA.

2.0 Material and Methods

2.1 Materials

TDP-43 with an N-terminal GST tag was purchased from ProteinTech Group (Chicago, IL) and caspase-7 was obtained from Biovision Inc. (Mountain View, CA). Human neuroglioma H4 cells were purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). The single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides: biotinylated TG6 (bt-TG6 TG X 6, 12 b), TG12, and TG4 were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). The 4-aminoquinoline compounds were synthesized by Fox Chase Chemical Diversity Center, Inc. (Doylestown, PA). The caspase inhibitors, Q-VD-OPh, Ac-DEVD-CHO and the caspase substrate, Ac-DEVD-AMC were purchased from EMD Biosciences (Philadelphia, PA). The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting: rabbit polyclonal anti-TDP-43, C-terminus (12892-1-AP, ProteinTech Group); mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (A01622, Genscript, Piscataway, NJ); rabbit monoclonal anti-cleaved caspase-3 (9664), rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase-7 (9491), rabbit monoclonal anti-cleaved PARP (5625), rabbit polyclonal anti-ATG7 (2631), rabbit monoclonal anti-LC3B (3868) were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA); rabbit polyclonal anti-CDK6 (sc-177), rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC6 (sc-11420) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

2.2 Inhibition of bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43

Displacement of bt-TG6 binding was measured using AlphaScreen® technology as previously described [33]. Briefly, assays contained TDP-43 (12.5 ng/mL, 0.1 nM), 10 μg/mL of both streptavidin donor beads and anti-GST acceptor beads with various concentrations of bt-TG6 and test compound in a final volume of 20 μL of 25 mM Tris, 0.1% CHAPS, pH 7.4 in white, opaque low volume 384-well plates. After 3 hr incubation at room temperature, the AlphaScreen® signal was measured using a Synergy 2 plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT). For IC50 determinations, the concentration of bt-TG6 was 0.75 nM and for inhibitor characterization experiments, the concentration ranged from 0.03 nM to 10 nM of bt-TG6. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM TG4 and was less than 10% of total binding. IC50 values were obtained from nonlinear regression fits of the data to a one-site binding model using Graph Pad Prism, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Comparison of competitive inhibition and mixed type inhibition models were evaluated using the F-test on global fits of the data also in Graph Pad Prism, version 5.0.

2.3 Immunoblotting

Samples were solublized in SDS sample buffer, heated at 95 °C for 10 min and loaded onto 4%–20% Tris-MOPS polyacrylamide gel (Genscript). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to Immobilon FL® PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and blocked for 1 hr with Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Primary antibodies were then added to the blocking buffer at a final dilution of 1:1000 to 1:2000 depending on the antibody, along with 0.1% Tween 20, and the membranes incubated overnight at 4 °C. After incubation, the membranes were washed in PBS + 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and anti-mouse (1:20,000) and/or anti-rabbit (1:5000) secondary antibodies conjugated to IRDye® 680 nm or 800 nm (Li-cor) were added to the membranes in Odyssey blocking buffer + 0.2% Tween 20 and 0.01% SDS followed by a 1 hr incubation at room temperature. After incubation, the membranes were washed in PBST, then rinsed with PBS and scanned using an Odyseey CLx infared imaging system (Li-cor).

2.4 Caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43 or Ac-DEVD-AMC

TDP-43 (2 μg/mL) was pre-incubated with test compound for 1 hr at room temperature in a final volume of 20 μL 25 mM Tris, 0.1% CHAPS, pH 7.4. After pre-incubation, caspase-7 was added at a final concentration of 5 U/mL and the assays incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C. Reactions were stopped using SDS sample buffer and subject to immunoblotting as described section 2.3.

Caspase-7 (2U/mL) was incubated with 1 μM Ac-DEVD-AMC and various concentrations of test compound in a final volume of 100 μL 25 mM Tris, 0.1% CHAPS, pH 7.4 in black opaque 96-well plates. Fluorescence with excitation λ = 360nm and emission λ = 460 nm was monitored at 10 min intervals for 90 min using a Synergy 2 plate reader.

2.5 Cell culture and treatments

Human neuroglioma H4 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-gluatamine, and 10% FBS. The day before the experiment, cells were plated onto tissue culture treated plates at ~80% confluence and then treated with test compounds on the following day for 24 hrs. After treatment, the media was removed and cells were lysed in SDS sample buffer and subject to immunoblotting as described in section 2.3. In some experiments, cells were lysed in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1% triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail by agitation and freeze-thaw. The lysate was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g resulting in the insoluble fraction (pellet) and soluble fraction (supernatant). These fractions were diluted in SDS sample buffer and subject to immunoblotting as described in section 2.3.

2.6 Solid-state immunoassay for cleaved poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) in H4 cells

H4 cells were plated at 80% confluence the day before the experiment in black opaque 96-well tissue culture treated plates. The cells were exposed to a series of concentrations of test compound ranging from 0.33 μM to 32 μM overnight in 100 μL complete growth medium. The media was removed and the cells fixed and permeabilized with 50 μL 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.25% triton X100 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, followed by washing in PBS and blocking with 50 μL 2.5% nonfat dry milk in PBST for 1 hr at room temperature. Rabbit monoclonal anti-cleaved PARP antibody was diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer and 50 μL added to each well followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C. Wells were then washed in PBST and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Cell Signaling) in blocking buffer for 2 hr at room temperature. Wells were then washed again and incubated with 1 mM H2O2 + 10 μM Amplex Red® (Invitrogen) in PBS for 1 hr. Fluorescence was then measured using the Synergy 2 plate reader (Biotek) at excitation λ = 530 nm and emission λ = 590 nm.

3.0 Results

3.1 4-Aminoquinoline probes are mixed inhibitors of bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43

In order to determine the mechanism of inhibition of oligonucleotide binding to TDP-43 by 4-aminoquinolines, we generated saturation binding isotherms for bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43 in the absence and presence of 1 μM, 3.2 μM and 10 μM of compound 1 (Figure 1, Figure 2A). Nonlinear regression global fits of the four curves to either a competitive binding model or a mixed inhibition model were compared using the F-test. The mixed inhibition was preferred with a P value of 0.0066, yielding a Ki value of 0.61 μM (95% CI: 0.48 – 0.74) and a value for α = 7.0 ± 3.5. The mixed model inhibition equation is a general equation where competitive, noncompetitive and uncompetitive inhibition are special cases [34]. The term (α) describes the mechanism of inhibition where α = 1 indicates noncompetitive inhibition, α = ∞ indicates competitive inhibition, and α ≫ 1 indicates uncompetitive inhibition [34]. Uncompetitive inhibitors actually increase the affinity of the substrate for the enzyme, in this case, the oligonucleotide affinity for TDP-43. Such inhibitors have higher affinity at saturating substrate concentrations. However, titrating compound 1 in the presence of a range of concentrations of bt-TG6 between 0.3 and 10 times its KD resulted in rightward shift in the dose-response curve for compound 1, thereby ruling out uncompetitive inhibition as a possible mechanism (Figure 2B). Plotting the resulting pIC50 values against the concentration of bt-TG6 yields a straight line with a slope of 0.51 (Figure 2C), which is significantly less than unity as would be predicted for a competitive inhibitor. However, a slope of 0 would be predicted for a pure noncompetitive inhibitor in such a plot. Therefore, 4-aminoquinoline mediated inhibition of nucleic acid binding to TDP-43 is best characterized as mixed inhibition, where these compounds bind to both free and occupied TDP-43, but with unequal affinities.

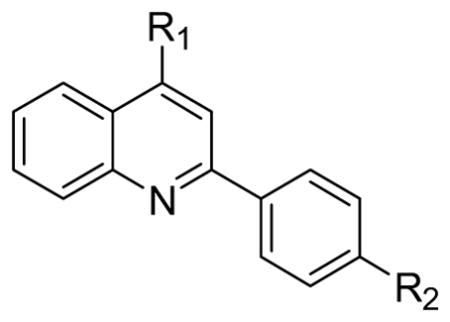

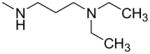

Figure 1.

Structures of 4-aminoquinoline 1 and 2 with affinity for TDP-43.

Figure 2. 4-aminoquinoline 1 exhibits mixed inhibition of bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43 using AlphaScreen® technology.

TDP-43 (0.1 nM) and 10 μg/mL of both streptavidin donor beads and anti-GST acceptor beads were incubated with various concentrations of biotinylated-TG6 (bt-TG6) and 1 for 3 hr at room temperature as described in section 2.2. (A) Saturation binding isotherms of bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43 in the absence (○), and presence of 1.0 μM (□), 3.2 μM (△), or 10 μM (◇) of 1. Data fit best to the mixed model inhibition equation compared to competitive inhibition equation (P < 0.01) in Graph Pad Prism® with a Ki value of 0.61 μM and α value of 7.0. (B) Dose-response curves for 1 in the presence of 0.32 nM (◇), 1.0 nM (△), 3.2 nM (□), 10 nM (○) bt-TG6. (C) Linear regression of pIC50 values from (B) vs log [bt-TG6] yields a slope of 0.51. Data represent mean ± S.E.M. of 4 determinations.

3.2 4-aminoquinoline probes stimulate caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43

Recently it has been shown that overexpression of TDP-43 results in cytotoxicity which is attenuated by caspase-mediated cleavage of TDP-43 [30]. Given the high affinity of TDP-43 for oligonucleotides with TG repeats [33], we hypothesized that oligonucleotide binding to TDP-43 might stabilize the protein and make it more resistant to caspase cleavage. Initially we tested both purified caspase-3 and caspase-7 for generating TDP-43 CTFs. Caspase-7 was more robust and required significantly less enzyme compared to caspase-3 for generating TDP-43 CTFs (data not shown) so all subsequent experiments were done using caspase-7. Preincubation of TDP-43 with 1 μM TG12 did modestly reduce the rate of caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43 by ~ 50% (data not shown). Surprisingly, however, preincubation with compound 2 (10 μM) dramatically increased the rate of caspase-7 mediated cleavage resulting in ~ 10 fold higher amounts of CTF35 compared to in the absence of compound after 1 hr incubation with caspase-7 (Figure 3A).

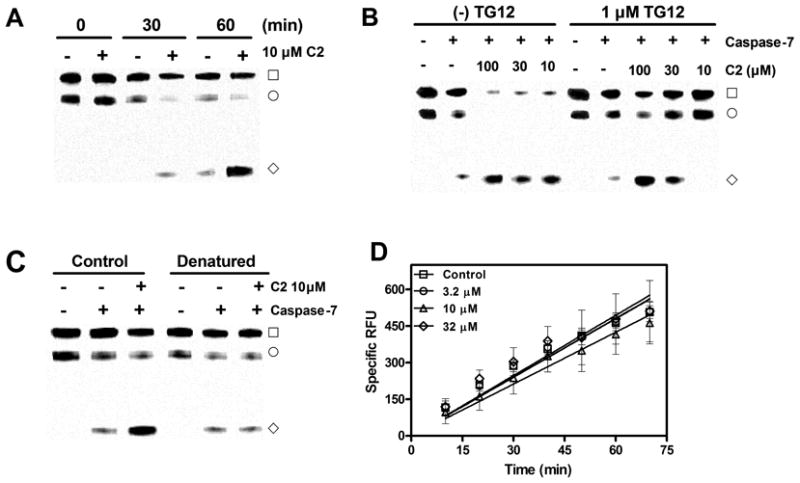

Figure 3. Stimulation of caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43 by 4-aminoquinolines is due to a specific interaction with TDP-43.

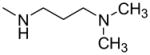

(A) Time dependence of 2 stimulation of caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43. TDP-43 (2 μg/mL) was preincubated with 10 μM of 2 for 1 hr followed by the addition of caspase-7 (5 U/mL). Reactions were incubated at 37 °C and terminated at the times indicated with SDS sample buffer followed by immunoblotting (section 2.3). (B) TG12 mediated antagonism of 2 stimulation of caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43. TDP-43 (2 μg/mL) was preincubated for 1 hr with indicated concentrations of 2 in the presence and absence of 1 μM TG12 followed by the addition of caspase-7. Reactions were terminated after 1 hr at 37 °C with SDS sample buffer. (C) Stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 requires correctly folded TDP-43. TDP-43 (0.2 mg/mL) was incubated in the absence and presence of 6 M guanidine HCl for 1 hr, followed by dialysis for 3 hr at room temperature. Dialyzed TDP-43 was then diluted to 4 μg/mL and preincubated in the presence and absence of 2 for 1 hr followed by addition of caspase-7 and subsequent 1 hr incubation at 37 °C. Blots are examples of single experiments that were replicated with similar results. (□) TDP-43, (◇) TDP-43 CTF35, (○) nonspecific band. (D). 4-aminoquinoline 2 does not affect caspase-7 mediated cleavage of Ac-DEVD-AMC. Caspase-7 (4 U/mL) was incubated with 1 μM Ac-DEVD-AMC in the presence and absence of indicated concentrations of 2 and change in fluorescence was monitored as described in section 2.4. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M of four determinations.

These unexpected results lead us to conduct several experiments to determine if the apparent stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 was due to an interaction with TDP-43 or due to some other nonspecific effect. Preincubation of compound 2 in the presence of 1 μM TG12 antagonized the stimulatory effect of compound 2 on caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43. As shown in Figure 3B, 1 μM TG12 completely inhibits the effect of 10 μM compound 2 on caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43 and essentially shifts the maximal effective dose from 10 μM to 100 μM of compound 2. This apparent antagonism of the stimulatory effect of compound 2 on caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 suggests that it is mediated by an interaction with TDP-43. In addition, we then tested whether or not compound 2 would be able to stimulate caspase-7 mediated cleavage of denatured TDP-43. Since caspases recognize a specific amino acid linkage, tertiary structure may not be necessary to observe cleavage by caspase-7. However, ligand binding requires tertiary structure and therefore denaturing TDP-43 should prevent binding of compound 2, while still allowing caspase-7 mediated cleavage. As shown in Figure 3C, predenatured TDP-43 was still subject to caspase-7 cleavage, but the effect of compound 2 (10 μM) was completely abolished. These data are consistent with the idea that compound 2 mediated stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 is due to a specific interaction with TDP-43 itself. However, in order to rule out any direct stimulatory effects on caspase-7, we monitored caspase-7 cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC in the presence of a range of concentrations of compound 2 up to 32 μM (Figure 3D). Compound 2 did not affect the rate of caspase-7 mediated cleavage of Ac-DEVD-AMC (Figure 3D). Therefore, taken together, these data indicate that it is the interaction between compound 2 and TDP-43 that promotes the cleavage of TDP-43 by caspase-7.

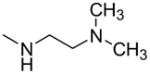

Since compound 2 binding to TDP-43 potentiated its cleavage by caspase-7, we then tested other structurally related compounds in order to investigate the SAR in relation to SAR for displacement of bt-TG6 binding. As shown in Table 1, compounds that had weaker affinities for TDP-43 binding generally did not stimulate caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43. While the 4-methoxyphenyl substitution was generally preferred over the 4-ethylphenyl for activity in bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43, it was critical for stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43. For example, compounds 2, 1, and 4 have the methoxy substitution and they all stimulate caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43, unlike their counterparts, compounds 3, 4, and 6, which have the ethyl substitution and are poor stimulators of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43. However, the 4-methoxyphenyl was not sufficient for the stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 as shown by compounds 7 and 8, both which had this substitution with differing R1 groups from the other compounds. These compounds were also weaker in bt-TG6 binding to TDP-43. Therefore both the R1 group and the 4-methoxyphenyl work together to improve binding affinity and augment caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43.

Table 1.

Structure-activity relationships for binding affinity at TDP-43 and stimulation of caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM)a TDP-43 binding | Stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 (%)b | |||||

| C# | R1 | R2 | 10 μM | 3.2 μM | 1.0 μM | |

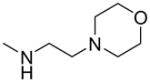

| 2 |

|

—OCH3 | 5.6 (2.7–11) | 123 ± 20 | 56 ± 22 | 10 ± 9 |

| 3 | —CH2CH3 | 20 (8.0–50) | 17 ± 5 | ND | ND | |

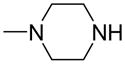

| 1 |

|

—OCH3 | 1.1 (0.55–2.2) | 117 ± 11 | 84 ± 24 | 15 ± 7 |

| 4 | —CH2CH3 | 3.3 (1.3–8.4) | 26 ± 8 | ND | ND | |

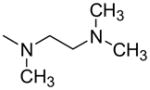

| 5 |

|

—OCH3 | 4.0 (2.1–7.6) | 124 ± 18 | 129 ± 24 | 14 ± 5 |

| 6 | —CH2CH3 | 7.6 (4.9–12) | 24 ± 9 | ND | ND | |

| 7 |

|

—OCH3 | 8.9 (5.4–15) | 4 ± 5 | ND | ND |

| 8 |

|

—OCH3 | 24 (7.8–74) | 9 ± 4 | ND | ND |

| 9 |

|

—H | >100 | c4 ± 2 | ND | ND |

IC50 values are the geometric mean and 95% confidence intervals of at least three determinations.

Values are the mean ± S.E.M. of three determinations and represent relative stimulation where 0% and 100% are equal to the intensity of CTF35 in the absence and presence of 10 μM T798, respectively.

Stimulation value at 32 μM compound.

ND. Not determined.

3.3 4-aminoquinoline probes reduce TDP-43 levels in H4 neuroglioma cells

Since these 4-aminoquinolines altered metabolism on TDP-43 in purified protein preparations, we hypothesized that they might affect TDP-43 levels in cells. We treated human neuroglioma H4 cells with compounds 1–4, along with compound 9 as a negative control and then measured TDP-43 levels by immunoblotting. Compounds 1–4 did modestly reduce TDP-43 levels in H4 cells, however compounds 1 and 2 were more potent and efficacious compared to compounds 3 and 4 (Figure 4A). This is similar to stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43, where the methoxy substitution was preferred over the ethyl substitution. In addition, compound 9 had no effect on TDP-43 levels at concentrations up to 32 μM which is consistent with both TDP-43 binding and caspase-7 cleavage data. These similarities in SAR suggest that the reduction in TDP-43 levels may be the result of compound binding to TDP-43.

Figure 4. Treatment with 4-aminoquinoline probes results in a caspase-dependent reduction in TDP-43 levels and increase in CTFs in human H4 cells.

(A) 4-aminoquinolines reduce TDP-43 levels in H4 cells with SAR similar to binding and stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43. H4 cells were plated onto 24-well plates the day before and then treated with test compound for 24 hrs, followed by lysis in SDS sample buffer and immunoblotting (section 2.3). (B) 4-aminoquinoline 1 and 2 reduce full length TDP-43 and increase TDP-43 CTFs in the triton X100 insoluble fraction, and to a lesser extent in the soluble fraction. H4 cells were plated in 6 well plates and treated with test compound as before and subject to fractionation of triton X100 soluble and insoluble fractions as described in section 2.5. (C) The effects of 1 on TDP-43 levels are attenuated by the caspase inhibitors Q-VD-OPh and Ac-DEVD-CHO. H4 cells were plated in 24-well plates and treated with 1 in the presence and absence of 10 μM Q-VD-OPh or Ac-DEVD-CHO for 24 hrs, followed by immunoblotting as before. Blots are examples of single experiments that were replicated with similar results.

If this reduction in TDP-43 levels was due to increased metabolism of TDP-43, then it would be predicted that an increase in TDP-43 CTFs would be present. Since TDP-43 CTFs tend to be insoluble, we separated lysate from H4 cells treated with compounds 1 and 2 into Triton X100 soluble and insoluble fractions and subject them to immunoblotting using a TDP-43 antibody directed to the C-terminus. Both compounds 1 and 2 dose-dependently reduced TDP-43 and increased TDP-43 CTF35 in the insoluble fraction (Figure 4B). TDP-43 levels were also reduced in the soluble fraction and also some CTF35 was observed at the highest concentration of compound tested. Since TDP-43 is metabolized by caspases, then the reduction in TDP-43 levels observed after treatment with compounds 1 or 2 should be inhibited by a caspase inhibitor. As shown in Figure 4C, the effects of compound 1 on TDP-43 levels was reversed by both the nonselective caspase inhibitor, Q-VD-OPh and the caspase 3/7 selective inhibitor Ac-DEVD-CHO. These data suggest that the reduction in TDP-43 is the result of an increase in caspase-dependent metabolism of TDP-43.

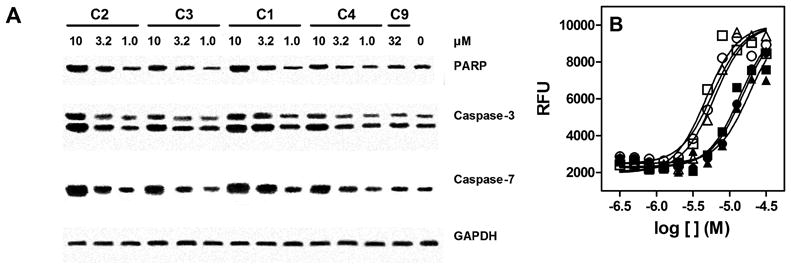

3.4 4-aminoquinoline probes activate caspases 3 and 7 and induced PARP cleavage in H4 cells

In order to determine if the reduction in TDP-43 levels might be the result of induction of caspases in cells, we treated cells with compounds 1–4, as well as compound 9 as a negative control and subject the cell lysate to immunoblotting for cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase-7 and cleaved PARP. Compounds 1–4 dose–dependently increased levels of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved caspase-7 and cleaved PARP in H4 cells after treatment for 24 hrs (Figure 5A). The immunoblots appeared to indicate that compounds 1 and 2 were more potent inducers of caspase activity than compounds 3 and 4, which is consistent with SAR at TDP-43. Therefore, to obtain a more quantitative determination, we established a solid state immunoassay in 96-well plates measuring the levels of cleaved PARP in H4 cells. As shown in Figure 5B, compounds with the methoxy substitution (1, 2, 5) were approximately 3-fold more potent at inducing PARP cleavage than compounds with the ethyl substitution (3, 4, 6). This is consistent with the SAR for bt-TG6 binding, which suggests that the induction of caspase activity in H4 cells is mediated by interactions with TDP-43.

Figure 5. 4-aminoquinoline probes activate caspase-3 and caspase-7 with subsequent PARP cleavage.

(A) H4 cells were plated onto 24 well plates the day before and treated with test compounds for overnight, followed by lysis in SDS sample buffer with subsequent immunoblotting (section 2.3). Blots represent single experiments that were replicated with similar results. (B) 4-aminoquinolines induce PARP cleavage with similar SAR to TDP-43 binding. Human H4 cells were treated with compounds 1 (□), 2 (○), 3 (●), 4 (■), 5 (△), and 6 (▲) at concentrations ranging from 0.33 to 32 μM overnight. Levels of cleaved PARP were measured using solid state immunoassay as described in section 2.6.

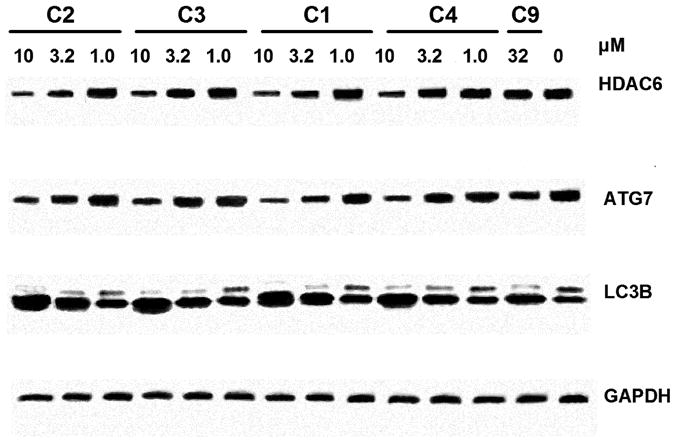

3.5 4-aminoquinoline probes reduce HDAC6 and ATG7 levels in H4 cells

Treatment with siRNA to TDP-43 also results in induction of caspases and increased PARP cleavage [9]. Since these 4-aminoquinolines behaved similarly with SAR consistent with binding to TDP-43, we wanted to investigate there effects on the expression of other proteins which are also affected by siRNA to TDP-43, such as HDAC-6, ATG-7, and CDK6 [9–11]. H4 cells were treated with compounds 1–4; 9 and subject to immunoblotting as before. Consistent with siRNA to TDP-43, compounds 1–4 modestly reduced levels of HDAC6 after 24 hrs in H4 cells, while there was no effect of compound 9 at 32 μM (Figure 6). Similarly, these compounds also reduced ATG7 and upregulated LC3B; however, compound 9 also had modest effects on these proteins at 32 μM. Unfortunately, we were not able to detect any changes on levels of CDK6 after treatment with compound in H4 cells (data not shown). Nonetheless, the effects on caspase induction, HDAC-6 and ATG7 suggest that these 4-aminoquinolines are interacting with TDP-43 in the cell and modulating its function.

Figure 6. 4-aminoquinoline probes reduce levels of HDAC6 and inhibit autophagy in H4 neuroglioma cells.

H4 cells were plated onto 24 well plates the day before and treated with test compounds for overnight, followed by lysis in SDS sample buffer with subsequent immunoblotting (section 2.3). Blots represent single experiments that were replicated with similar results.

4.0 Discussion

We have discovered and characterized a series of 4-aminoquinolines which bind to TDP-43 and modulate its metabolism and function. Based on inhibitor characterization experiments, these compounds are mixed inhibitors, binding to both free and occupied TDP-43 with differing affinities, at a site distinct from the oligonucleotide binding site. Unexpectedly, we discovered that binding of these compounds to TDP-43 promotes caspase-7 induced cleavage of TDP-43. This effect on caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 was antagonized by TG12 and prevented by denaturing TDP-43, indicating that it was due to a direct and specific interaction with TDP-43 itself. In addition, subtle structural features, especially the 4-phenylmethoxy substitution, were required to observe stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 which also suggests a specific interaction. In cells, these compounds reduce TDP-43 levels and increase levels of TDP-43 CTFs via upregulation of caspases 3 and 7 with SAR consistent with displacement of TDP-43 oligonucleotide binding. Similar to treatment with TDP-43 siRNA, these compounds also reduce expression of both HDAC6 and ATG7, thereby inhibiting of some of the cellular functions of TDP-43 previously described. These data indicate that inhibition of nucleic acid binding of TDP-43 by these 4-aminoquinolines has functional consequences in vitro.

Like other hnRNPs, TDP-43 contains two RNA recognition motifs, designated RRM1 and RRM2, both of which participate in oligonucleotide binding [3]. Even though the inhibitor characterization data indicate that 4-aminoquinoline binding occurs at a site distinct from oligonucleotide binding, they could still bind to one of the RRM domains. It is unlikely that these compounds bind to both RRM domains simultaneously given there low molecular weight and therefore they may not behave as competitive inhibitors compared to larger oligonucleotides. One possible scenario is that the 4-aminoquinolines bind to either RRM1 or RRM2 resulting in a conformational change that has lower affinity for oligonucleotide resulting in dissociation. In fact, the effect of 4-aminoquinoline binding on caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 suggests that there is a conformational change upon 4-aminoquinoline binding. Interestingly, two caspase cleavage sites, Asp89 and Asp169 are slightly before, or part of RRM1, respectively [30–32]. This may suggest that 4-aminoquinoline binding occurs distal to RRM1, potentially RRM2, which then induces a conformational change making the cleavage sites more accessible to caspase-7.

The stimulation of caspase-7 cleavage of TDP-43 resulting from 4-aminoquinoline binding is interesting in light of data suggesting that abnormal overexpression of TDP-43 results in neurodegeneration in vivo [25, 28, 29]. Moreover, in cell culture, it has been demonstrated that overexpression of TDP-43 is cytotoxic and this toxicity is attenuated by caspase mediated metabolism of TDP-43 [30]. As a result, pharmacological stimulation of TDP-43 metabolism may mitigate neurodegeneration caused by abnormal overexpression of TDP-43. We tried to test this hypothesis by transfecting H4 cells with TDP-43 DNA with subsequent exposure to TDP-43 inhibitors. However, we did not achieve sufficient transfection efficiency or upregulation of TDP-43 to observe measurable TDP-43 induced cytotoxicity (data not shown). Nonetheless even if treatment with 4-aminoquinolines does attenuate TDP-43 induced toxicity, inhibition of TDP-43 function itself may also result in cytotoxicity. As we have shown here in normal cells, binding to TDP-43 activates apoptotic pathways via induction of caspase-3/7, which is consistent with siRNA to TDP-43 as previously described [9]. Whether or not this phenomenon occurs in situations where TDP-43 is overexpressed remains to be determined.

Since small molecule inhibitors of TDP-43 have not yet been described, we investigated the effects of our 4-aminoquinoline probes in cells and hypothesized that TDP-43 inhibitors would behave like TDP-43 siRNA. Consistent with this hypothesis, we did observe a reduction in HDAC-6 and ATG7, as well as upregulation of LC3B, induction of caspases 3/7 and increased PARP cleavage [9–11]. However, we did not see any changes in CDK6 and pRb as previously reported [9]. It should be noted that pharmacological inhibition can have different results compared to inhibition by siRNA [35]. While siRNA will inhibit all functions of a protein of interest, pharmacological inhibition leaves the protein still intact and thus certain functions may be preserved [35]. In addition, cells were exposed to concentrations 3–10 fold higher than the IC50 in bt-TG6 binding. Therefore complete pharmacological inhibition may not have been achieved. Moreover, it is entirely possible that off-target effects may have also confounded the results. For example, these 4-aminoquinolines are structurally related to chloroquine, a known autophagy inhibitor, and so the effects on ATG7 and LC3B may be due to chloroquine-like effects. Indeed, there was an effect of our negative control, compound 9, on ATG7 and LC3B levels (Figure 6), albeit at higher concentrations and to a lesser extent than the other compounds tested. Nonetheless, despite these confounding factors, the purpose of these experiments was not to delineate functions of TDP-43 as previously defined by siRNA, but rather to validate if in fact these compounds were interacting with TDP-43 and determine if functional consequences resulted from such interactions in cells. Given that these compounds inhibited certain of the described cellular functions of TDP-43 with the same rank order of potency as for displacement of bt-TG6 binding supports this conclusion.

In addition to the work described here, additional chemistry lead optimization as well as selectivity screening, especially at other nucleic acid binding proteins, remains to be done to improve upon these compounds and further validate our results. The data described here as well as what has been reported by other investigators, suggests that TDP-43 inhibitors have the potential to either attenuate or exacerbate neurodegeneration resulting the dysfunction associated with TDP-43. The potential therapeutic utility for agents which block nucleic acid binding to TDP-43 and stimulate its clearance in neurodegenerative disease such as ALS is difficult to evaluate with our current understanding. Nonetheless, compounds that bind to TDP-43 are useful biochemical probes to further elucidate both the normal and pathological functions of TDP-43.

Highlights.

4-aminoquinolines are mixed inhibitors of oligonucleotide binding to TDP-43

Caspase-7 mediated cleavage of TDP-43 is enhanced upon 4-aminoquinoline binding

4-Aminoquinolines reduce TDP-43 levels in H4 cells via a caspase-dependent mechanism

Exposure to 4-aminoquinolines induces caspases 3 and 7, leading to lower TDP-43 levels

Similar to siRNA to TDP-43, 4 aminoquinolines reduce HDAC6, ATG7, and increase LC3B

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the financial support of the National Institutes of Health which supported work described here (1R21NS072749-01). We also thank Drs. Aaron Pawlyk and Sergey Ilyin for helpful discussions and support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Joel A. Cassel, Email: jcassel@alsbiopharma.com.

Mark E. McDonnell, Email: mmcdonnell@fc-cdci.com.

Venkata Velvadapu, Email: vvelvadapu@fc-cdci.com.

Vyacheslav Andrianov, Email: v_andrianov@hotmail.com.

Allen B. Reitz, Email: areitz@alsbiopharma.com.

References

- 1.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Multiple roles of TDP-43 in gene expression, splicing regulation, and human disease. Front Biosci. 2008;13:867–878. doi: 10.2741/2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R46–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo PH, Doudeva LG, Wang YT, Shen CK, Yuan HS. Structural insights into TDP-43 in nucleic-acid binding and domain interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ou SH, Wu F, Harrich D, Garcia-Martinez LF, Gaynor RB. Cloning and characterization of a novel cellular protein, TDP-43, that binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAR DNA sequence motifs. J Virol. 1995;69:3584–3596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3584-3596.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36337–36343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buratti E, Brindisi A, Pagani F, Baralle FE. Nuclear factor TDP-43 binds to the polymorphic TG repeats in CFTR intron 8 and causes skipping of exon 9: a functional link with disease penetrance. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1322–1325. doi: 10.1086/420978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buratti E, Dork T, Zuccato E, Pagani F, Romano M, Baralle FE. Nuclear factor TDP-43 and SR proteins promote in vitro and in vivo CFTR exon 9 skipping. EMBO J. 2001;20:1774–1784. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala YM, Pagani F, Baralle FE. TDP43 depletion rescues aberrant CFTR exon 9 skipping. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1339–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayala YM, Misteli T, Baralle FE. TDP-43 regulates retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation through the repression of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3785–3789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800546105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bose JK, Huang CC, Shen CK. Regulation of autophagy by the neuropathological protein TDP-43. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:44441–44448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SH, Shanware NP, Bowler MJ, Tibbetts RS. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated proteins TDP-43 and FUS/TLS function in a common biochemical complex to co-regulate HDAC6 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34097–34105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald KK, Aulas A, Destroismaisons L, Pickles S, Beleac E, Camu W, Rouleau GA, Vande Velde C. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) regulates stress granule dynamics via differential regulation of G3BP and TIA-1. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1400–1410. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colombrita C, Zennaro E, Fallini C, Weber M, Sommacal A, Buratti E, Silani V, Ratti A. TDP-43 is recruited to stress granules in conditions of oxidative insult. J Neurochem. 2009;111:1051–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu-Yesucevitz L, Bilgutay A, Zhang YJ, Vanderweyde T, Citro A, Mehta T, Zaarur N, McKee A, Bowser R, Sherman M, Petrucelli L, Wolozin B. Tar DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43) associates with stress granules: analysis of cultured cells and pathological brain tissue. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freibaum BD, Chitta RK, High AA, Taylor JP. Global analysis of TDP-43 interacting proteins reveals strong association with RNA splicing and translation machinery. J Proteome Res. 2009;9:1104–1120. doi: 10.1021/pr901076y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwong LK, Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. TDP-43 proteinopathy: the neuropathology underlying major forms of sporadic and familial frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buratti E, Baralle FE. The molecular links between TDP-43 dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Adv Genet. 2009;66:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(09)66001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Kwong LK, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia and beyond: the TDP-43 diseases. J Neurol. 2009;256:1205–1214. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strong MJ. The syndromes of frontotemporal dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2008;9:323–338. doi: 10.1080/17482960802372371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawlyk AC, Cassel JA, Reitz AB. Current nervous system related drug targets for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2053–2073. doi: 10.2174/138161210791293024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banks GT, Kuta A, Isaacs AM, Fisher EM. TDP-43 is a culprit in human neurodegeneration, and not just an innocent bystander. Mamm Genome. 2008;19:299–305. doi: 10.1007/s00335-008-9117-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagier-Tourenne C, Cleveland DW. Rethinking ALS: the FUS about TDP-43. Cell. 2009;136:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liscic RM, Grinberg LT, Zidar J, Gitcho MA, Cairns NJ. ALS and FTLD: two faces of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:772–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatom JB, Wang DB, Dayton RD, Skalli O, Hutton ML, Dickson DW, Klein RL. Mimicking aspects of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Lou Gehrig’s disease in rats via TDP-43 overexpression. Mol Ther. 2009;17:607–613. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baloh RH. TDP-43: the relationship between protein aggregation and neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. FEBS J. 2011;278:3539–3549. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gendron TF, Josephs KA, Petrucelli L. Review: transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43): mechanisms of neurodegeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2010;36:97–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen-Plotkin AS, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. TAR DNA-binding protein 43 in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:211–220. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wils H, Kleinberger G, Janssens J, Pereson S, Joris G, Cuijt I, Smits V, Ceuterick-de Groote C, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S. TDP-43 transgenic mice develop spastic paralysis and neuronal inclusions characteristic of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3858–3863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912417107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wegorzewska I, Bell S, Cairns NJ, Miller TM, Baloh RH. TDP-43 mutant transgenic mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18809–18814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908767106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki H, Lee K, Matsuoka M. TDP-43-induced death is associated with altered regulation of BIM and Bcl-xL and attenuated by caspase-mediated TDP-43 cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13171–13183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.197483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dormann D, Capell A, Carlson AM, Shankaran SS, Rodde R, Neumann M, Kremmer E, Matsuwaki T, Yamanouchi K, Nishihara M, Haass C. Proteolytic processing of TAR DNA binding protein-43 by caspases produces C-terminal fragments with disease defining properties independent of progranulin. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1082–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YJ, Xu YF, Dickey CA, Buratti E, Baralle F, Bailey R, Pickering-Brown S, Dickson D, Petrucelli L. Progranulin mediates caspase-dependent cleavage of TAR DNA binding protein-43. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10530–10534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3421-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassel JA, Blass BE, Reitz AB, Pawlyk AC. Development of a novel nonradiometric assay for nucleic acid binding to TDP-43 suitable for high-throughput screening using AlphaScreen technology. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15:1099–1106. doi: 10.1177/1087057110382778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Copeland R. Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss WA, Taylor SS, Shokat KM. Recognizing and exploiting differences between RNAi and small-molecule inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1207-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]