Abstract

Oxidative stress is the main etiological factor behind the pathogenesis of various diseases including inflammation, cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Due to the spin trapping abilities and various pharmacological properties of nitrones, their application as therapeutic agent has been gaining attention. Though the antioxidant properties of the nitrones are well known, the mechanisms by which they modulate the cellular defense machinery against oxidative stress is not well investigated and requires further elucidation. Here, we have investigated the mechanisms of cytoprotection of the nitrone spin traps against oxidative stress in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC). Cytoprotective properties of both the cyclic nitrone 5,5-dimethyl-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) and linear nitrone alpha-phenyl N-tert-butyl nitrone (PBN) against H2O2-induced cytoxicity were investigated. Preincubation of BAEC with PBN or DMPO resulted in the inhibition of H2O2–mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis. Nitrone-treatment resulted in the induction and restoration of phase II antioxidant enzymes via nuclear translocation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) in oxidatively-challenged cells. Furthermore, the nitrones were found to inhibit the mitochondrial depolarization and subsequent activation of caspase-3 induced by H2O2. Significant down-regulation of the pro-apoptotic proteins p53 and Bax, and up-regulation of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and p-Bad were observed when the cells were preincubated with the nitrones prior to H2O2–treatment. It was also observed that Nrf-2 silencing completely abolished the protective effects of nitrones. Hence, these findings suggest that nitrones confer protection to the endothelial cells against oxidative stress by modulating phase II antioxidant enzymes and subsequently inhibiting mitochondria-dependent apoptotic cascade.

Keywords: nitrones, spin traps, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, Nrf-2

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress has been a hallmark of pathogenesis behind a number of disorders including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [1–3], cardiovascular disorders [4, 5], ischemia/reperfusion injury [6], neurodegenerative disorders [7, 8] and cancer [9]. In biological systems oxidative stress is induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS), a group of highly reactive molecules that include hydroxyl radical (HO•), peroxyl radical (ROO•), superoxide anion radical (O2•−) or non-radical compounds such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or singlet oxygen (1O2). It has been reported that approximately 1–3% of the oxygen consumed by the body is converted into ROS [10]. Increased production of ROS in the vasculature leads to endothelial dysfunction [11, 12], which acts as the main etiological factor behind several cardiovascular disorders (CVD) such as atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure [13, 14]. To attenuate the ROS-mediated pathogenesis against oxidative stress, use of natural antioxidants such as vitamin E, vitamin C, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and theaflavins [15–17], as well as synthetic antioxidants such as SOD-mimetics (e.g. M40403 and M40419), salens (e.g. EUK134), and GPX mimetics (ebselen, BXT-51072) [17, 18], have been suggested. However dietary supplementation with natural antioxidants such as vitamins E, C, and carotenoids showed no positive outcomes in CVD clinical trials [19] and in some cases contributed to increased mortality [20–22]. Hence the use of targeted synthetic antioxidants has gained attention due to their rich chemistry and opportunities for modulating their physico-chemical properties as well as their target specificity to enzyme active sites, organelles, or cells for optimal pharmacological activity.

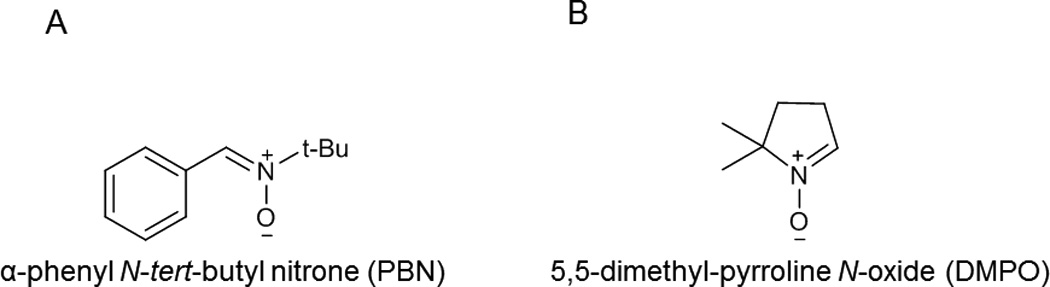

Nitrones are compounds with a general common moiety of R1R2C=N+O−(R3) (where R1 = H; R1, R2, R3 = alkyl group), and are used extensively as the spin-traps for their ability to form adducts with transient free radicals [23]. To date, there are two major types of spin traps (Fig. 1) that are commonly used for spin trapping, the linear nitrones (e.g., α-phenyl N-tertiary-butyl nitrone (PBN) (Fig. 1A) and cyclic nitrones (e.g., 5,5-dimethyl-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) (Fig. 1B). Due to their unique chemical properties and biological activity [24], nitrones have been used as therapeutic agents against several ROS-related disorders such as brain injury [25], ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiomyopathy [26], visual impairment [27], neuronal damage [28], and cancer [29, 30]. Moreover, nitrones also showed potential as therapeutic agent against stroke [31, 32] and can lead to the improvement of cerebral blood flow in animal models [33]. Previous reports suggest that both the PBN and DMPO are capable of conferring protection to endothelial cells against oxidative stress-induced injury, but the mechanisms of this protection remains unclear [26, 34–36]. Decrease in nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability has been known to be a hallmark in ROS-induced endothelial dysfunction [37]. NO has several beneficial vascular effects such as vasodilatation, regulation of vascular smooth muscle proliferation, and expression of cellular adhesion molecules [38, 39]. Furthermore, it has been reported that the O2•− adduct of the nitrone spin traps may undergo unimolecular decomposition to yield NO [40, 41]. Hence the application of nitrones may lead to the improvement of the vascular health by counterbalancing the loss of NO bioavailability under oxidative stress. Previous experimental evidences also indicate that application of nitrones confers protection against ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by salvaging the mitochondrial bio-energetics and enzymatic activities of the mitochondrial ETC complexes [26].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of nitrone spin traps. (A) Linear nitrone, α-phenyl N-tert-butyl nitrone (PBN); and (B) cyclic nitrone, 5,5-dimethyl-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO)

The phase II antioxidant enzymes play a key role in protecting cells and tissues from oxidative and electrophilic stresses. Induction of these antioxidant enzymes is regulated primarily by the antioxidant or electrophile response elements (ARE/EpRE), which are found in the 5'-flanking region of many phase II and antioxidant genes [42–44] such as heme oxygenase-1(HO-1), NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and glutathione reductase (GR). The coordinated action of these phase II enzymes ensures effective detoxification of oxidative and electrophilic species. For example HO-1 is known to possess antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-thrombotic, and anti-inflammatory properties [45], while GPx and GR function coordinately to counterbalance oxidative stress. GPx catalyzes the direct decomposition of H2O2 via the oxidation of reduced glutathione (GSH) to GSSG, which is then converted to GSH by glutathione reductase (GR) [46]. The enzyme NQO1 catalyzes the two-electron reduction of electrophilic quinone compounds to form the less reactive hydroquinones and serves as an antioxidant enzyme [47].

The transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) plays a critical role in trans-activating phase II enzyme expression and thus has become an important therapeutic target for natural and synthetic antioxidants against oxidative stress [48–51]. Upon activation, Nrf-2 translocates to the nucleus and binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) to modulate the expression of the important phase II enzymes [52–54]. Aside from its role in regulating carcinogen detoxification and cellular antioxidative defense machineries, Nrf-2 also has anti-inflammatory functions [55, 56] and can therefore act as a potential therapeutic target for various antioxidant drugs.

In this study, we identified the molecular mechanisms of cytoprotection by nitrones during oxidative stress. The treatment of endothelial cells with nitrone resulted in inhibition of H2O2–induced cytotoxicity accompanied by significant lowering of ROS generation. In addition, nitrones suppressed the H2O2–induced mitochondrial-dependent activation of caspase-3 and nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor Nrf-2 with subsequent activation of the phase II antioxidant enzymes. Together, these studies uncover novel aspects of the cytoprotective mechanisms of nitrones and provide evidence of their potential use to inhibit oxidative-stress induced apoptosis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

BAEC were purchased from Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA. Tissue culture materials such DMEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, trypsin and MEM-non essential amino acids were purchased from Gibco, Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). DMPO was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD) and PBN was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Primary antibodies (against p53, Bax, Bcl-2, p-Bad and Nrf-2) and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL), while protein estimation kit was purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit was obtained from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ,). 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA), Rhodamine 123, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), NADPH, glucose-6-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 2,6-dichloroindophenol, EDTA, GSH, glutathione reductase, and o-phthalaldehyde were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).). The Nrf-2-siRNA and scramble siRNA-Control were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA 91355).

2.2. Cell culture and treatment

BAEC were cultured in DMEM medium with 4.5 g/L D-glucose and 4 mM L-glutamine, and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2.5 mg/L endothelial cell growth supplement, and 1% MEM-non essential amino acids at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 20% O2. The medium was changed every 2–3 days and cells were subcultured once they reached 90–95% confluence. For cytotoxicity studies, BAEC were pretreated with nitrone alone (0–100 µM) or in the presence of 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h, while for cytoprotection studies, cells were preincubated with nitrone (0–50 µM) for 24 h and then subsequently treated with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h.

2.3. Cell viability assay (MTT Assay)

Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay following the manufacturers protocol as previously described and the formation of the formazan was measured using a Varian microplate reader absorbance 570 nm (50 MPR, Foster City, CA) [57]. BAEC were grown to 80% confluency and incubated with nitrone (0–100 µM) for 24 h to assess their cytotoxicity. For cytoprotection studies BAEC were preincubated with nitrone (0–100 µM) for 24 h, then treated with 100 µM H2O2 and incubated for additional 24 h. Data were calculated as the percentage of inhibition by the following formula (eqn 1.):

| (1) |

where At and As indicated the absorbance of the test substances and solvent control, respectively.

2.4. Detection of Apoptosis

For flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis treated cells were stained with annexin FITC-conjugated annexin V (1 µg/ml) and propidium iodide (PI) (0.5 µg/ml) in a Ca2+-enriched binding buffer for 30 min at room temperature as previously described [58]. Percentage of apoptosis, was assessed using a Becton Dickinson FACS Calibur (San Jose, CA, USA) and data were analyzed using Cell Quest version 3.3 software. For confocal microscopy studies, BAEC were cultured over glass coverslips reaching 60–70% confluency, prior treatment, and subsequently stained with Annexin V-FITC (1 µg/ml) and DAPI (1 µM) at 37 °C for 1h. Images were captured using an Olympus FluoView-1000 confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) at 40 X magnification (emission filters 570 nm for DHE and 495 nm for DAPI. Fluorescence intensities of 100 cells from different fields were calculated using the software FV10-ASW 2.1 (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA). Results were presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3).

2.5. Detection of Reactive oxygen Species (ROS)

For flow cytometric analysis of ROS, treated BAEC were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and incubated with 25 µM of DCFH-DA at 37 °C for 30 min. ROS generation was assessed by flow cytometry at excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 nm and 535 nm, respectively. For the assessment of ROS by confocal microscopy studies, BAEC cells were washed after treatments with PBS three times and subsequently incubated with 25 µM of the fluorogenic probe 2',7'- dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by nuclei staining with DAPI (1 µM) for 1h. Images were then captured by Olympus FluoView-1000 confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) and fluorescence intensities of 100 cells from different fields were calculated using the method described above. Results were presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (n = 3).

2.6. Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential ψ (MMP)

Changes in MMP in BAEC treated for varying time period (0–24 h) were determined using flow cytometry by staining cells with the fluorescent probe Rhodamine 123 (5 µg/mL). After treatment BAE cells were incubated with rhodamine 123 (5 µg/mL) for 60 min in the dark at 37 °C, harvested and suspended in PBS. The MMP was then determined using FACS by measuring the fluorescence intensity (FL-1, 530 nm) [59]. All experiments were done in triplicates and the percent of mean fluorescence intensity (% MFI) was plotted for each sample.

2.7. Determination of caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was determined by using the DEVD-7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin (DEVD-AFC) assay as described previously [60]. After treatment, cells were incubated in a cyto-buffer (10% glycerol, 50 mM Pipes, pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) containing 20 µM of the tetrapeptide substrate DEVD-AFC (Enzyme Systems Products, Livermore, CA). Release of free AFC was determined using a Cytofluor 4000 fluorometer (Perseptive Company, Framingham, MA, USA; Filters: excitation; 400 nm, emission; 508 nm).

2.8. Preparation of cell extracts, western blot analysis, and silencing

Nuclear translocation of the transcription factor Nrf-2 in nitrone-treated BAEC was detected by western blotting and confocal microscopy. For confocal analysis, BAEC were fixed after treatments with 2% para-formaldehyde followed by incubation with permeabilization solution (0.1% Na-citrate, 0.1% Triton) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were first blocked using 5% BSA solution o/n at 4 °C and incubated with goat polyclonal anti-Nrf-2 antibody (1:200 dilutions, Santa Cruz, sc-722) for 3 h at room temperature followed by the incubation with anti-goat FITC-conjugated IgG antibody (1:150 dilutions) and DAPI (1 µM) for 2 h at room temperature. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and images were taken by Olympus FluoView-1000 confocal microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) at 60X magnification.

Subcellular localization of Nrf-2 was analyzed by western blotting BAEC nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts. Briefly, cells were washed once with cold PBS, scraped off the dish and collected by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, and fractions were collected by adding extraction reagents as indicated by manufacturers at 200:11:100 (v/v) (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of protein were loaded and mouse monoclonal anti-glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:1000 dilutions, Santa Cruz, sc-35448) and mouse monoclonal anti-lamin B (1:1000 dilutions, Santa Cruz, sc-365962) antibodies were used as the loading controls for the cytosolic and nuclear fractions.

Western blot analysis was also performed to determine the expression levels of p53, Bax, Bcl-2 and p-BAD proteins in untreated, H2O2-treated, and nitrone-pre incubated H2O2-treated BAEC. After treatment cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS (pH 7.4) and lysed with BD lysis buffer (1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/ml aprotinin and 10 µg/ml leupeptin, pH 7.4) for 30 min and centrifuged at 12000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The protein concentration of the clear supernatant was measured using Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Hercules, CA), taking bovine serum albumin as standard. In separate experiments, the membrane was incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-p53 antibody (1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz, sc-126), mouse monoclonal anti-Bax antibody (1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz, sc-70407), mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-2 antibody (1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz, sc-7382), mouse monoclonal anti-p-Bad (ser 136) antibody (1:500 dilution, Santa Cruz, sc-7999) and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz, sc-47778) overnight at 4 °C. After washing with tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20, the membranes were then incubated with HRP conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescence kit from Thermo Scientific, and the bands were quantified densitometrically by Bio-Rad Chemi Doc (1708070) system using the software Quantity One (Bio-Rad).

For silencing experiments, BAEC cells were transfected at 60% confluency with 50 nM Nrf-2-siRNA (sequence for targeting Nrf-2 was 5-TTGACAATTATCATTTCTATT-3’, Qiagen, Cat-No: 1027423) or siRNA-control (Qiagen, Cat-No: 1027292) using DharmaFect (Dharmacon, Inc, IL, T-2002-02) following manufacturer protocols. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were used to assess silencing by immunoblotting using goat polyclonal anti-Nrf-2 antibody (1:500 dilutions, Santa Cruz, sc-722) and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:1000 dilution, Santa Cruz, sc-47778) as loading control and for experiments showed under results.

2.9. Assessment of phase II antioxidant enzymes

After treatment BAEC were collected, resuspended in 300 µl of ice cold assay buffers, sonicated, followed by centrifugation at 14–18000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant were collected and stored at −80 °C. Cellular HO-1 activity was measured according to previous procedure [61]. Briefly, cells were resuspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 2 mM with MgCl2, followed by three cycles of freeze-thawing and sonicated on ice before centrifugation at 18000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. HO-1 assay was initiated by addition of 100 µl (~200–250 µg protein) of cell extracts to 200 µl of reaction mix containing 0.5 mM NADPH, 2 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 1 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 0.2 mM hemin, and 1 mg/ml rat liver cytosol (as a source of biliverdin reductase) in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 2 mM MgCl2. The reaction was conducted for 1 h at 37 °C in the dark and terminated by addition of 300 µl chloroform. The extracted bilirubin was measured by the difference in absorbance between 464 nm and 530 nm (extinction coefficient = 40 mM−1 cm−1) and HO activity was expressed as pmol of bilirubin formed per mg of cellular protein.

Cellular NQO1 activity was determined using dichloroindophenol as the two-electron acceptor, as described before [46]. Ten µl of cell extract was added to a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.08% Triton X-100, 0.25 mM NADPH, 80 µM 2,6-dichloroindophenol (DCIP) in absence or presence of 25 µM dicoumarol, a potent inhibitor of NQO1. The two-electron reduction of DCIP was monitored at 600 nm at 25 °C for 3 min. Specific activity of NQO1 was calculated using the extinction coefficient of 21.0 mM−1 cm−1, and expressed as nanomole of DCIP reduced per minute per milligram of cellular protein.

Cellular GPx activity was measured as previously described [46]. Ten µl of cell extract were added to a reaction mixture containing 170 µl of 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA and 2 mM sodium azide, 30 µl of 10 mM GSH, 30 µl of glutathione reductase (2.4 U/ml), and 30 µl of 1.5 mM NADPH (prepared in 0.1% NaHCO3). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 min. and after the addition of 30 µl of 2 mM H2O2, the rate of NADPH consumption was monitored at 340 nm, 37 °C for 5 min. GPx activity was calculated using the extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1 cm−1, and expressed as nanomole of NADPH consumed per minute per milligram of cellular protein.

Cellular GR activity was measured following the protocol described before [46]. Briefly, to a reaction mixture containing 230 µl of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 1 mM EDTA, 10 µl of cell extract and 30 µl of 20 mM GSSG were added. The mixture was pre-warmed at 37 °C for 3 min. and the reaction was started by the addition of 30 µl of 1.5 mM NADPH (prepared in 0.1% NaHCO3). The subsequent consumption of NADPH was monitored at 340 nm, 37 °C for 5 min. GR activity was calculated using the extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1 cm−1 and expressed as nanomole of NADPH consumed per minute per milligram of cellular protein.

2.10. Measurement of intracellular GSH

Total GSH was determined by fluoromtreic methods as previously described [46]. Briefly, 10 µl of cell extracts were incubated with 12.5 µl of 25% meta-phosphoric acid, and 37 µl of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer containing 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, at 4 °C for 10 min. The samples were centrifuged at 13000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant (10 µl) was incubated with 0.1 ml of o-phthalaldehyde solution (0.1% in methanol) and 1.89 ml of the above phosphate buffer for 15 min at room temperature. Fluorescence intensity was then measured using a Perkin-Elmer LS50B fluorimeter (2H2 INC, Ontario, Canada) at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm and an emission wavelength of 420 nm. Cellular GSH content was calculated using a concurrently run GSH (Sigma) standard curve, and expressed as nanomole of GSH per milligram of cellular protein.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean of at least three independent experiments along with standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses of data were done by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Student-Newman-Keul test by using Sigma plot 12.0. The p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Inhibition of H2O2 –induced cytotoxicty and apoptosis of BAEC by nitrones

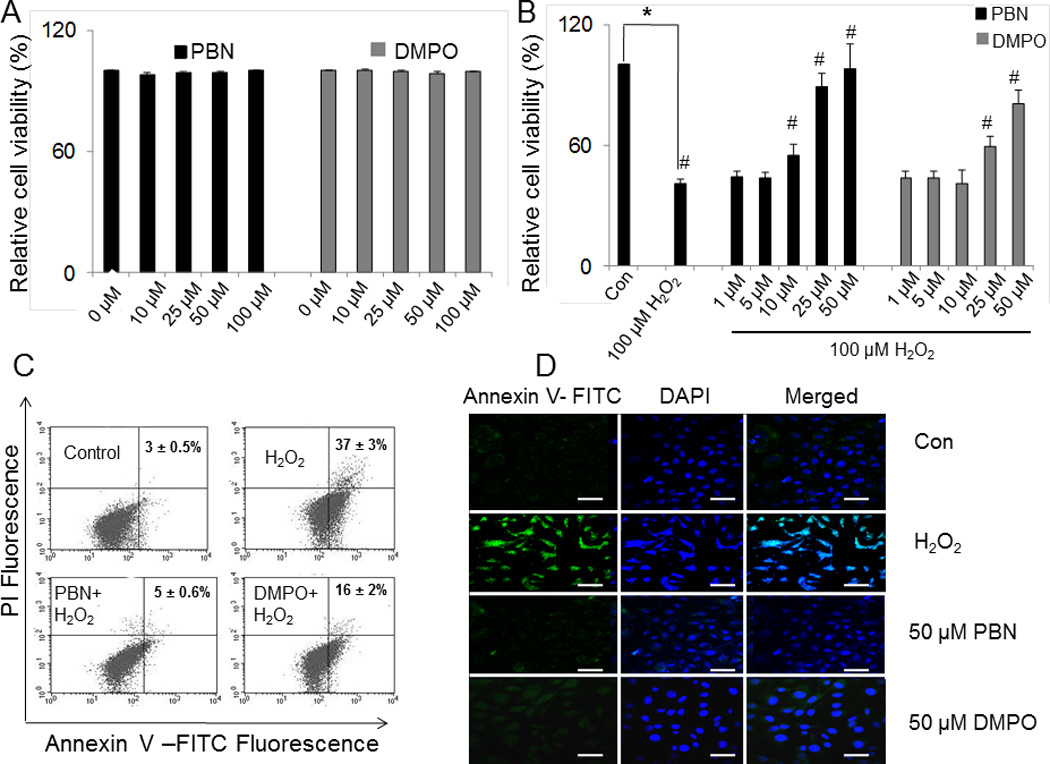

Treatment of BAEC with nitrone for 24 h did not exhibit significant cytotoxicity up to 100 µM (Fig. 2A). Incubation of BAEC with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h showed loss of viability by ~ 62% (Fig. 2B). To evaluate the cytoprotective properties of nitrones, BAEC were preincubated for 24 h with different concentrations of the spin traps prior to the addition of 100 µM H2O2 for additional 24 h of incubation. A dose-dependent increase in cell viability was also observed when cells were pretreated with nitrone (0–50 µM). Addition of 25 µM and 50 µM PBN increased viability of H2O2-BAEC treated cells to 88% and 98%, respectively, while at DMPO concentrations of 25 µM and 50 µM, viability of H2O2-treated cells was also increased to 57% and 80%, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Effect of nitrones on H2O2-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in BAEC. (A) Cytotoxicity of nitrone (0–100 µM) alone determined by MTT assay. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM, where n = 6. (B) Cell viability of BAEC treated with H2O2 (100 µM) alone and those preincubated with nitrone (0–50 µM) as determined by MTT assay. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (untreated cells), and #p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated cells, where n = 6. (C) Induction of apoptosis in H2O2-treated BAEC and subsequent inhibition by nitrone-pretreatment. Apoptotic cells were analyzed flow cytometrically, and a dot plot representation of Annexin-V-FITC-fluorescence (x-axis) vs. PI-fluorescence (y-axis) has been displayed. The figure represents the best of three independent experiments. (D) Immunofluorescence study of Annexin V-FITC positive apoptotic cells treated with H2O2 (100 µM) alone for 24 h and those preincubated with nitrone (0–50 µM). The right panel corresponds to the merged image of FITC-fluorescence and DAPI-fluorescence, used to stain the nuclei. Bar represents 10 µm.

The effect of nitrones in H2O2-induced apoptosis in BAEC was then investigated. Flow cytometry data show pretreatment of cells with 50 µM PBN resulted in a significant decrease of apoptotic population to 5%, whereas same concentration of DMPO reduced apoptosis to 16% (Fig. 2C). In addition, the anti-apoptotic effects of nitrones were also evaluated by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2D). Treatment of BAEC with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h resulted in 37% of cells undergoing apoptosis as illustrated by Annexin V/PI staining (Fig. 2D) compared to 3% observed in cells treated with control diluents (PBS control). Treatment of BAEC with 100 µM of H2O2 for 24 h resulted in a 3.5–fold significant increase in apoptotic cells as shown by the increase in Annexin V-FITC+ compared to control cells. Pretreatment with 50 µM PBN reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells to levels comparable to controls, whereas 50 µM DMPO induced a significant reduction by 1.6-fold. These results suggest that the onset of apoptosis in oxidatively challenged BAEC is significantly inhibited by the nitrones.

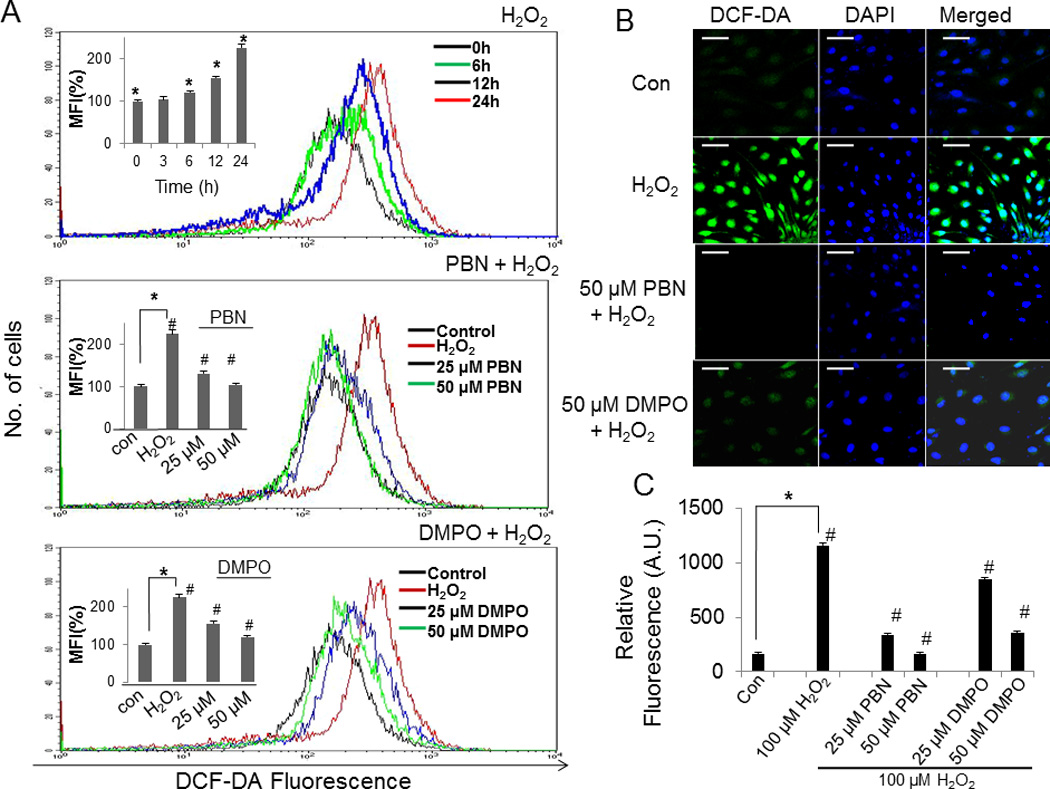

3.2. Decrease of ROS generation in H2O2-treated BAEC by nitrones

Significant amount of ROS generation was observed in H2O2-treated BAEC as indicated by both flow cytometry and confocal microscopy studies. BAEC treated with 100 µM H2O2-resulted in a time dependent-accumulation of ROS as observed by FACS (Fig. 3A). Pretreatment with either 25 µM or 50 µM PBN prior to the addition of 100 µM H2O2 resulted in a significant decrease of ROS generation to levels compared to control as shown by the percentage of mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of DCF-fluorescence (Fig. 3A). Similarly preincubation with 25 µM or 50 µM DMPO before the addition of H2O2 resulted in a decrease of fluorescence up to 1.6-and 1.2-folds respectively (Fig. 3A). Consistently, confocal microscopy studies also revealed a significant increase in ROS generation in BAEC treated with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h as observed in Figs. 3B and 3C, but pretreatment with nitrones showed a drastic reduction of DCF-fluorescence in H2O2–treated cells (Figs. 3B and C). Preincubation of H2O2–treated BAEC with 25 µM or 50 µM PBN resulted in the decrease of DCF-fluorescence by 3.4- and 7-folds respectively, whereas pretreatment with similar concentrations of DMPO resulted in 1.4- and 3.2-folds decrease in DCF-fluorescence (Figs. 3B and C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of nitrones on H2O2-induced ROS generation in BAEC. (A) BAEC were treated with 100 µM H2O2 alone at various time points (0–24 h) in the absence or presence of nitrone (0–50 µM). After treatment, cells were incubated with 25 µM of DCFH-DA at 37 °C for 30 min in the absence of light and ROS generation was then assessed using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD) with excitation at 488 and emission at 535 nm. (Inset), Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) form the histogram analysis of all three sets such as H2O2-alone (various time intervals), PBN + H2O2 and DMPO + H2O2 were presented as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (untreated cells), and #p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated cells, where n = 3. (B) Confocal images of BAEC treated with H2O2 (100 µM) alone and those preincubated with nitrone (0–50 µM). The right panel corresponds to the merged image of DCF-fluorescence and DAPI-fluorescence, bar represents 10 µm. (C) A plot of relative DCF- fluorescence obtained from the average of 100 cells. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (H2O2-untreated cells), and #p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated cells, where n = 3.

3.3. Inhibition of H2O2 – induced mitochondrial depolarization in BAEC by nitrones

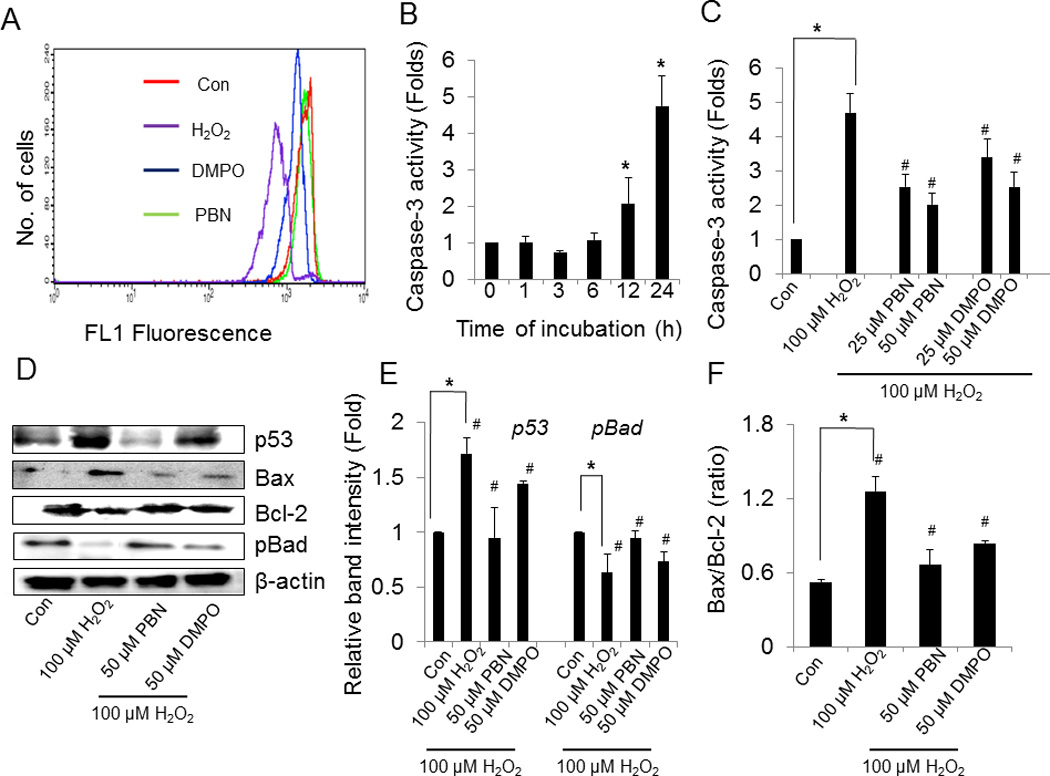

To further understand the mechanisms involved in nitrone cytoprotection, we determined their effect of nitrones on mitochondrial depolarization. Treatment of BAEC with 100 µM H2O2 for 16 h resulted in the depletion of mitochondrial membrane potential as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A). A gradual decrease in MMP by almost 58% was observed in BAEC cells treated with 100 µM H2O2 for 16 h with rhodamine 123 fluorescence (Fig. 4A). Pretreatment of BAEC with 50 µM nitrone prior H2O2-treatment restored mitochondrial potential to levels found in control cells (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that nitrones inhibit H2O2-induced mitochondrial depolarization.

Fig. 4.

Effect of nitrones on H2O2-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, caspase-3 activation and modulation of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins in BAEC. (A) Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). BAEC were treated with 100 µM H2O2 in the absence or presence of nitrone (0–50 µM) for 24 h. After treatment cells were stained with rhodamine 123 and incubated for 60 min, and MMP was measured using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD) with excitation at 488 and emission at 535 nm. Results are expressed as a representative histogram analysis. (B) Time-dependent activation of caspase-3 by H2O2. To determine time-dependent activation of caspase-3 by H2O2, BAEC were treated with 100 µM H2O2 at various time points (0–24 h) and caspase-3 activity was determined by using the 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin assay (AFC) linked to the tetrapeptide DEVD as described in “materials and methods” section. Results are represented as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (untreated cells). (C) Inhibition of H2O2-induced caspase-3 activation by nitrones. To determine nitrone-induced inhibition of caspase-3 activity, BAEC were preincubated with nitrone (0–50 µM) and then treated with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h. After treatment cells were incubated with DEVD-AFC. Finally the release of free AFC was monitored using Cytofluor 4000 fluorimeter (excitation, 400 nm; emission, 508 nm). Results are represented as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (untreated cells), and #p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated cells, where n = 3. (D) Modulation of pro-and anti-apoptotic proteins by the nitrones in H2O2-treated BAEC. Expression levels of p53, Bax, Bcl-2 and p-Bad in BAEC treated with H2O2 in the absence and presence of nitrone were monitored by western blotting. (E), (F) Densitometric analysis of the expressions of p53, p-Bad and Bax/ Bcl-2 ratio. Results are represented as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (untreated cells), and #p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated cells, where n = 3.

3.4 Inhibition of H2O2 – induced activation of caspase-3 by in BAEC by nitrone spin traps

Treatment of BAEC with 100 µM H2O2 showed a gradual increase of caspase-3 activity reaching a maximum level of ~ 5-fold after 24 h of H2O2-treatment (Fig 4B). To determine whether nitrone affects H2O2-induced caspase-3 activation, BAEC were pretreated with 25 µM and 50 µM of nitrone prior to the addition of H2O2. Preincubation with PBN resulted in inhibition of the H2O2-induced caspase-3 activity by 2- and 2.5-folds at 25 µM and 50 µM (Fig. 4C), respectively, whereas at similar doses of DMPO, ~ 3.4- and 2.5-folds decrease were observed, respectively (Fig. 4C).

3.5. Modulation of pro-and anti-apoptotic proteins by nitrones in H2O2–treated BAEC

Treatment of BAEC with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h resulted in a distinct increase in the levels of the pro-apoptotic proteins p53 and Bax to 1.7- and 1.5-folds respectively, while the expression of the pro-survival Bcl-2 decreased to 0.78-fold (Fig. 4D). The expression level of phospho (p)-Bad was also found to be reduced to 0.6-fold in H2O2-treated cells, compared to controls. Addition of 50 µM nitrone prior H2O2–treatment significantly increased p-Bad and Bcl-2 levels and were accompanied by the down regulation of Bax and p53 (Figs. 4D and 4E). Since cell survival in the early phase of apoptosis depends mostly on the balance between the pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl-2 family, the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 acts as an important determinant of cell fate. Bax/Bcl-2 ratio increased in H2O2-treated BAEC, but when cells were preincubated with the nitrones prior to H2O2-treatment, the ratio was decreased significantly thereby shifting the balance to cell survival (Fig. 4E). These results clearly indicate that nitrone–pretreatment results in the attenuation of H2O2–induced apoptosis signaling in BAEC.

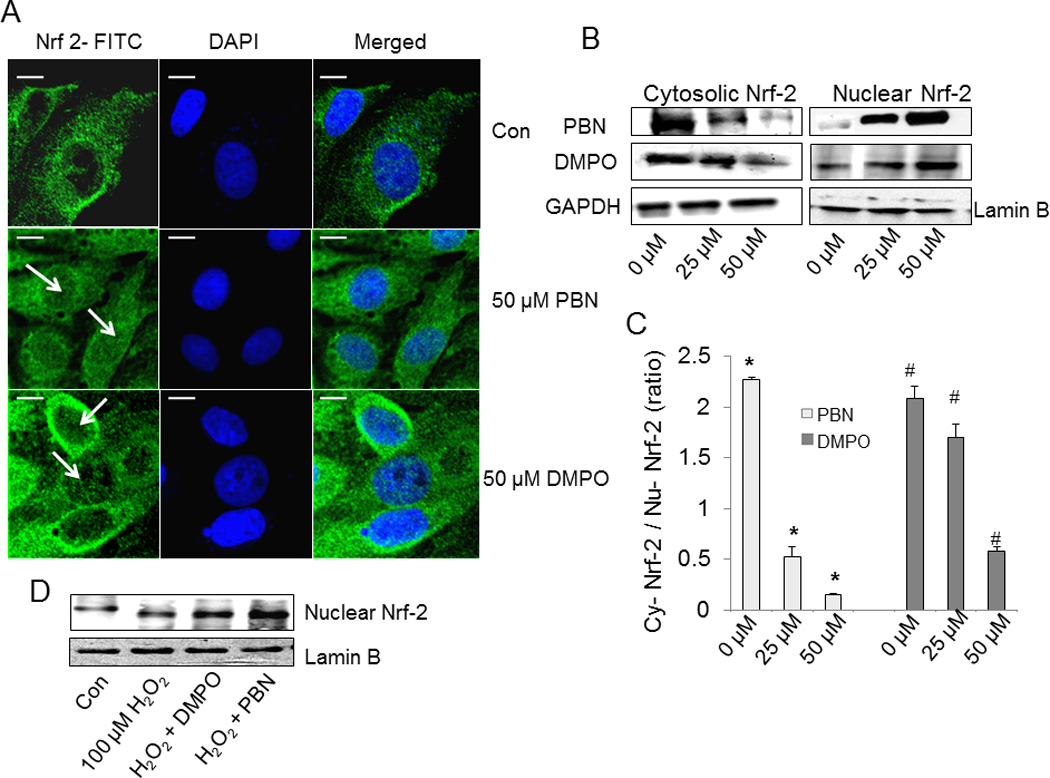

3.6. Nitrones regulate nuclear translocation of Nrf-2

To elucidate the antioxidant mechanism of nitrone spin traps, we investigated the effect of nitrones on Nrf-2 subcellular localization. Treatment of BAEC with 50 µM PBN showed increased nuclear localization of Nrf-2 compared with PBS-controls cells (Fig 5A). Similarly, a fraction of Nrf-2 was also found in the nucleus in cells treated with 50 µM DMPO (Fig 5A). Furthermore, subcellular fractionation studies showed increased nuclear localization of Nrf-2 accompanied by a decrease in the cytoplasmic fraction in PBN-treated cells (Figs. 5B and 5C). Similarly, DMPO also induced the nuclear translocation of Nrf-2 as observed by immunoblots of subcellular lysates of cells treated with 50 µM DMPO (Figs. 5B and 5C). In addition, increase nuclear Nrf-2 was observed in BAEC cells pretreated with 50 µM of the nitrone prior to the addition of 100 µM H2O2 (Fig. 5D). These results clearly indicated that nitrone-treatment resulted in the nuclear translocation of Nrf-2 in the endothelial cells.

Fig. 5.

Effect of nitrones on nuclear translocation of Nrf-2. (A) BAEC were treated with nitrone (0–50 µM) for 24 h. After treatment, cells were immunostained with goat polyclonal anti-Nrf-2 antibody (1:200 dilutions) followed by anti-goat FITC-conjugated IgG antibody (1:150 dilutions) and DAPI (1 µM) to stain the nucleus. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and images were taken by Olympus FluoView-1000 confocal microscope at 60 X magnification. The right panel corresponds to the merged image of FITC-fluorescence and DAPI-fluorescence, bar represents 10 µm. The figure represents the best of three independent experiments (n = 3) (B) Western blot analysis of the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of nitrone-treated BAEC, using anti- Nrf-2 primary antibody (1:500 dilution). Anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:1000 dilution) and anti-lamin B (1:1000 dilution) antibodies were used as loading controls for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. The figure represents three independent experiments (n = 3) (C) Densitometric ratio of cytosolic vs. nuclear Nrf-2 in nitrone-treated BAEC, calculated from the respective band intensities. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (PBN-untreated cells) and #p < 0.05 vs. control (DMPO-untreated cells), where n =3. (D) Immunoblot analysis of the nuclear extracts of untreated, H2O2-treated, and nitrone-preincubated H2O2-treated BAEC for Nrf-2, using anti- Nrf-2 primary antibody (1:500 dilution) and anti-lamin B (1:1000 dilution) as the loading control. The figure represents three independent experiments (n = 3).

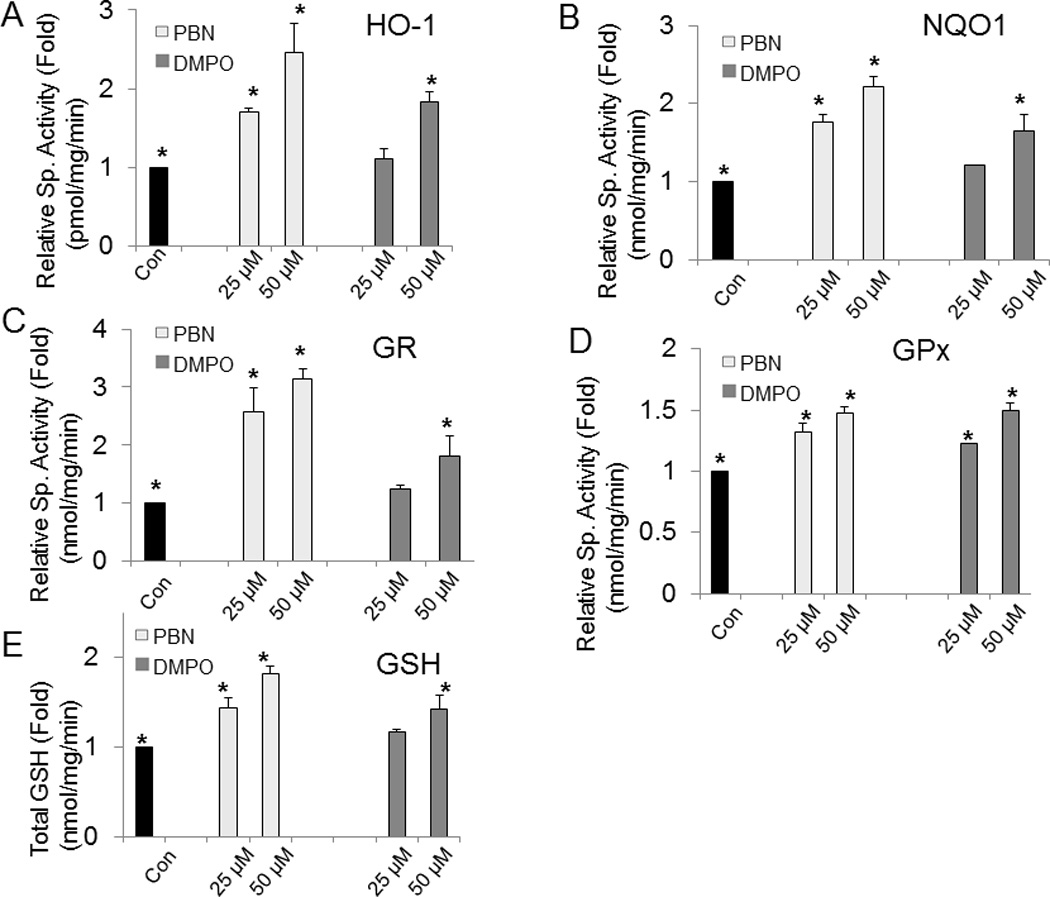

3.7. Induction of cellular phase II enzymes activity by nitrones alone in BAEC

Since activation of Nrf-2 is associated with the induction of phase II antioxidant enzymes, we determined the effect of nitrones on the activity of various phase II enzymes. Treatment of BAEC with 25 µM or 50 µM PBN induced HO-1 activity by 1.7- and 2.4-folds respectively (Fig. 6A), while at same concentrations of DMPO, the HO-1 activity was increased by about 1.1- and 1.8-folds, respectively (Fig. 6A). Similarly in the presence of 25 µM and 50 µM PBN, the activity of NQO1 increased to 1.8- and 2.2-folds, respectively, while in the presence of 25 µM and 50 µM DMPO, NQO1-activty was increased to 1.2- and 1.7–folds, respectively (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effect of nitrones on the activities of phase II enzymes and intracellular GSH in BAEC. BAEC were incubated with different concentrations of nitrone (0–50 µM) for 24 h, and phase II enzyme activities were spectrophotometrically assessed. Following the protocol described in “materials and methods” section, activities from the cell extracts were determined for (A) HO-1, (B) NQO1, (C) GR, (D) GPx and (E) GSH, respectively. Results are represented as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (nitrone-untreated cells), where n = 3.

Similar effects were observed in GR and GPx enzyme activities (Figs. 6C and D). GR activity was also found to be highly up-regulated in PBN-treated BAEC. In the presence of 25 µM or 50 µM PBN, the GR activity levels were remarkably increased up to 2.5- and 3.1-folds respectively, compared to the untreated cells. At similar PBN concentrations, GPx activity levels were increased to 1.3- and 1.4-folds respectively. DMPO also showed increase in both GPx and GR activity levels (Figs. 6C and D). For example, in presence of 50 µM DMPO, GPx and GR activity levels were increased up to 1.5- and 1.8-folds respectively. These data suggest that treatment of BAEC with the nitrones result in significant activation of the antioxidant enzymes, and that the ability of PBN to induce enzyme activity is more robust compared to DMPO.

Intracellular GSH levels were found to be significantly increased when BAEC were treated with nitrone. In presence of 50 µM PBN, GSH level was found to be increased up to 1.8-fold, while at similar concentration of DMPO, the intracellular GSH was increased to 1.4-fold, compared to control (Fig. 6E).

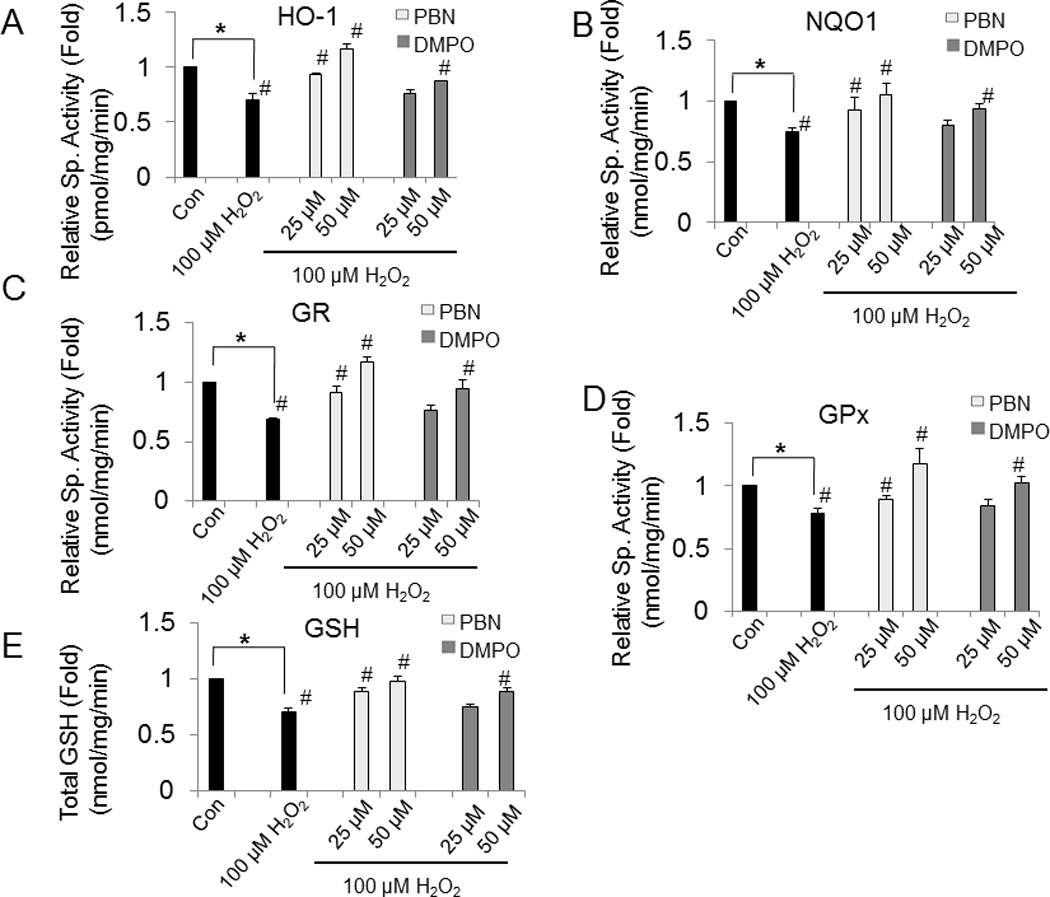

3.8. Induction of cellular phase II enzymes by nitrones in H2O2–treated BAEC

Next, we determine whether nitrone affects the phase II enzyme activities during oxidative stress. Treatment of BAEC with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h resulted in significant reduction of HO-1, NQO1, GR and GPx activities by 30%, 35%, 40% and 24%, respectively, compared to control (Fig. 7). Pretreatment of BAEC with 50 µM nitrone showed that HO-1, NQO1, GR and GPx activities were increased to the levels statistically similar to control (Fig. 7). The intracellular GSH level was found to be decreased by 29% in H2O2–challenged BAEC, but a significant recovery of thiol levels was observed when the cells were preincubated with nitrones. Pretreatment of BAEC with 50 µM nitrone resulted in the recovery of intracellular GSH by 25% and 20%, respectively (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7.

Effect of nitrones on the activities of phase II enzymes and intracellular GSH in H2O2-treated BAEC. BAEC were preincubated with different concentrations of nitrone (0–50 µM) and then challenged with 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h. After treatment cell extracts were prepared and assayed for (A) HO-1, (B) NQO1, (C) GR (D) GPx and (E) GSH, respectively. Results are represented as mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 vs. control (untreated cells), and #p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated cells, where n = 3.

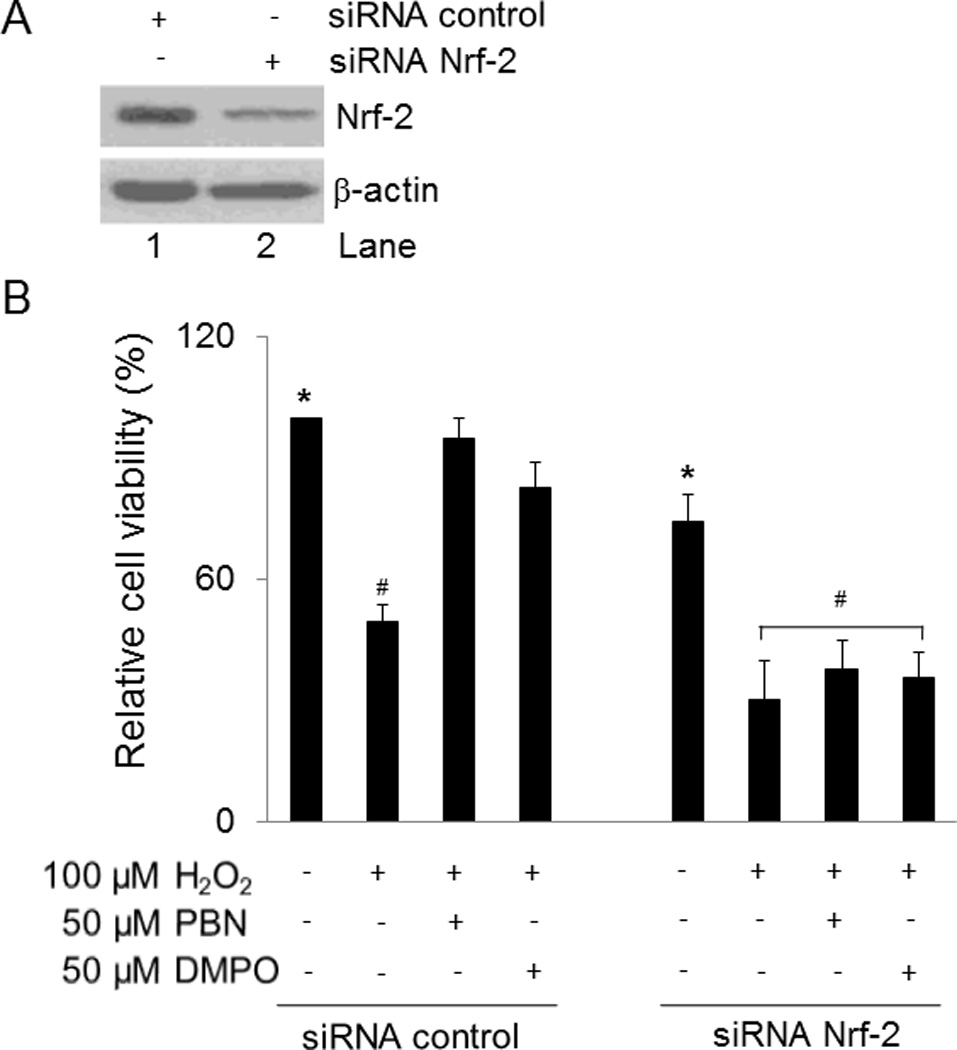

3.9. Nitrone-induced cytoprotection is mediated by Nrf-2

To delineate the role of Nrf-2 in nitrone-induced cytoprotection against oxidative stress, Nrf-2 expression was silenced in BAEC cells. BAEC cells transfected with siRNA-Nrf-2 showed a significant reduction of Nrf-2 expression compared with cells transfected with siRNA-Control (Fig. 8A). Next, the cytoprotective properties of nitrone were evaluated in siRNA-Nrf-2 or siRNA-Control BAEC cells treated with H2O2. Cells transfected with siRNA-Nrf-2 or siRNA-Control were treated with 50 µM PBN or DMPO for 24 h before addition of 100 µM H2O2 for 24 h. Silencing of Nrf-2 reduced cell viability by 20% compared to siRNA-Control cells (Fig. 8B). A minor but not significant loss of DMPO cytoprotection was observed in the siRNA-Control cells treated with H2O2, but this effect was not observed with PBN (Fig. 8B). Silencing of Nrf-2 reduced viability for 20% compared to siRNA-Control cells even in the absence of cytotoxic agents (Fig. 8B, * p < 0.05). Nitrone-induced cytoprotection against H2O2 was completely abrogated in siRNA-Nrf-2 cells reaching levels found in H2O2-siRNA-Control treated cells (Fig. 8B, # p > 0.1). Collectively, these results indicate that Nrf-2 plays the key role in nitrone-induced cytoprotection against oxidative stress.

Fig. 8.

Nrf-2 is necessary for nitrone cytoprotection. (A) BAEC were transfected with a specific siRNA-Nrf-2 or a scramble siRNA-Control and efficiency of silencing was evaluated by immunoblotting 48 h post-transfection. The results are a representative of three experiments (n = 3). (B) Cytoprotective properties of nitrone was evaluated by MTT assays in BAEC transfected with siRNA-Nrf-2 or siRNA-Control treated 48 h post-transfection with 50 µM nitrone for 24 h followed by treatment with 100 µM H2O2 or diluent control for 24 h. Results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3), *p < 0.05 siRNA-Control NT vs. siRNA-Nrf-2 NT and #p > 0.1 siRNA-Control H2O2-treated vs. siRNA-Nrf-2 H2O2-treated, PBN + H2O2 or DMPO + H2O2-treated cells.

4. Discussion

Structurally, spin traps are simple molecules but they impart rich chemistries and biological properties which made them relevant pharmacological agents [24]. For instance, nitrones can exhibit redox properties by virtue of their oxidation state [62], react with a variety of free radicals [63–65], decompose to NO after addition to O2•– [40, 41], can form biologically relevant species such as hydroxamic acid, aldehydes, and nitrous acid [62] and more effectively traps O2•– at mildly acidic pH than in neutral pH which makes spin trapping relevant in ischemic conditions or cancer cells [66]. Although the mechanism of nitrone-protection is still obscure, earlier studies suggest that the spin trapping properties play an important role in nitrone-mediated cardioprotection [67, 68] but recent experimental evidences pointed out the involvement of other mechanisms of protection other than spin trapping [26]. For example, PBN is also known to suppress the expression levels of heat shock proteins, c-Fos, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), when used against several ROS-induced disorders [32]. How nitrones modulate the antioxidant defense mechanisms and apoptosis signaling against oxidative stress are yet to be fully understood. Hence in the present study, we had investigated the nitrone-mediated induction of cellular antioxidants and phase II enzymes via Nrf-2 pathway in BAEC treated with H2O2. Inhibitory effects of nitrones on the activation of mitochondrial–dependent apoptotic cascade were also explored simultaneously in H2O2-treated BAEC.

Nitric oxide plays an essential role in the regulation of normal vascular homeostasis and vessel integrity and most of the NO donating drugs are limited by their stability, controlled delivery and targeting properties [69]. Hence the controlled-NO releasing properties of nitrones could impart unique pharmacological properties [40], which are not associated with other widely employed anti-oxidant drugs.

We observed that pretreatment with nitrone significantly inhibited H2O2-mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis in BAEC (Fig. 2). Hydrogen peroxide induces damage to the whole cell mainly because of its ability to cross membranes and so is usually referred to as a global oxidant. Treatment of BAEC with 100 µM H2O2 resulted in a time–dependent increase in ROS, which was found to be ameliorated by nitrones (Fig. 3). Generation of ROS in oxidatively challenged cells lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and simultaneous release of cytochrome c, which further activates caspase-3, the central executioner of apoptosis [70, 71]. However, upon preincubation of BAEC with nitrone prior to H2O2-treatment, the mitochondrial dependent activation of caspase-3 was found to be inhibited to a significant extent (Figs. 4A–4C).

It is reported that under oxidative stress the pro-apoptotic protein Bad translocates to the mitochondria and heterodimerizes with Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL and facilitates Bax-dependent mitochondrial depolarization, finally resulting in the activation of caspase-3 [70]. Bad remains in an inactive form due to the phosphorylation at ser-136 residue by upstream kinases like Akt, and this inhibits its association with Bcl-2 [72]. Phosphorylated (p)-Bad dissociates from Bcl-2 and is sequestered in the cytosol [73] to promote cell survival. The pro-apoptotic protein p53 is activated under oxidative stress [74] and also known to play a significant role in activation and mitochondrial translocation Bax [75]. H2O2-treated BAEC, showed an up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic proteins like p53 and Bax along with the concomitant down regulation of the anti-apoptotic p-Bad and Bcl-2. Preincubation with nitrone, however, reverses the effect and inhibits the up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins (Figs. 4D–4E).

To elucidate the mechanisms of cytoprotective property of nitrones, we investigated other antioxidative mechanisms other than direct spin trapping. Since it is well established that the transcription factor Nrf-2 can modulate the expressions and activities of several phase II antioxidant enzymes after being translocated to the nucleus [52–54]. Western blot and confocal studies were performed with BAEC treated with different concentrations of the nitrone alone. Interestingly, we observed that higher accumulation of Nrf-2 in nucleus upon treatment with higher nitrone concentration (Fig. 5). As anticipated, activities of the phase II enzymes such as HO-1, NQO1, GR, and GPx, along with the intracellular GSH levels were also increased due to nitrone-treatment (Fig. 6). Similarly depletion of the antioxidant enzyme activities in oxidatively challenged BAEC were also found to be restored due to nitrone pretreatment (Fig. 7). The fact that Nrf-2 translocation and induction of phase II enzyme activities were observed with nitrone treatment alone, and only Nrf-2 translocation with significant decrease in antioxidant activities were observed with H2O2 treatment alone, indicate that the nitrones confer protection through Nrf-2 activation and perhaps through salvaging of enzymes activity from direct H2O2–mediated enzyme inactivation. To confirm the role of Nrf-2 in nitrone-mediated cytoprotection, BAEC were transfected with siRNA-Nrf-2 and MTT assay was performed. Silencing of Nrf-2 resulted in the complete attenuation of nitrone-induced protection of BAEC against H2O2 (Fig. 8).

Although both PBN and DMPO had conferred significant protection against H2O2-toxicity, better protection was observed in PBN-treated cells. DMPO was found to be protective at a concentration of 50 µM. On the other hand, at 25 µM PBN showed enhanced protective properties than DMPO. Our earlier work showed that DMPO is a better spin trap for O2•− and HO2• radicals than PBN-type nitrones [76] in spite that PBN confers better protection than DMPO in this study. Also as demonstrated by others where PBN was shown to confer better cardioprotection than DMPO in isolated rat hearts against doxorubicin-induced toxicity [77]. Previously, we have shown that the PBN-based nitrones confer robust protection against H2O2-mediated toxicity [34]. The lipophilicity of PBN was found to be much higher than that of DMPO with log k′W values of 1.64 and 0.31, and that the rate of internalization inside the cells is also higher for PBN compared to DMPO [34]. The increased lipophilicity of PBN may lead to its better compartmentalization inside the cells and this may account for the enhanced antioxidant property of PBN than DMPO. DMPO has been widely employed as spin trapping agents with more superior properties than that of PBN-based nitrones in terms of reactivity to O2•− and HO2• [76]. Therefore, attempts had been made to conjugate cyclic nitrones to several target specific groups in order to facilitate their delivery to specific subcellular compartments [34, 78–80] since the poor target specificity of some of the natural antioxidants such as vitamin E, vitamin C, or lipoic acid are limiting their applications against ROS-induced CVDs [19, 81, 82].

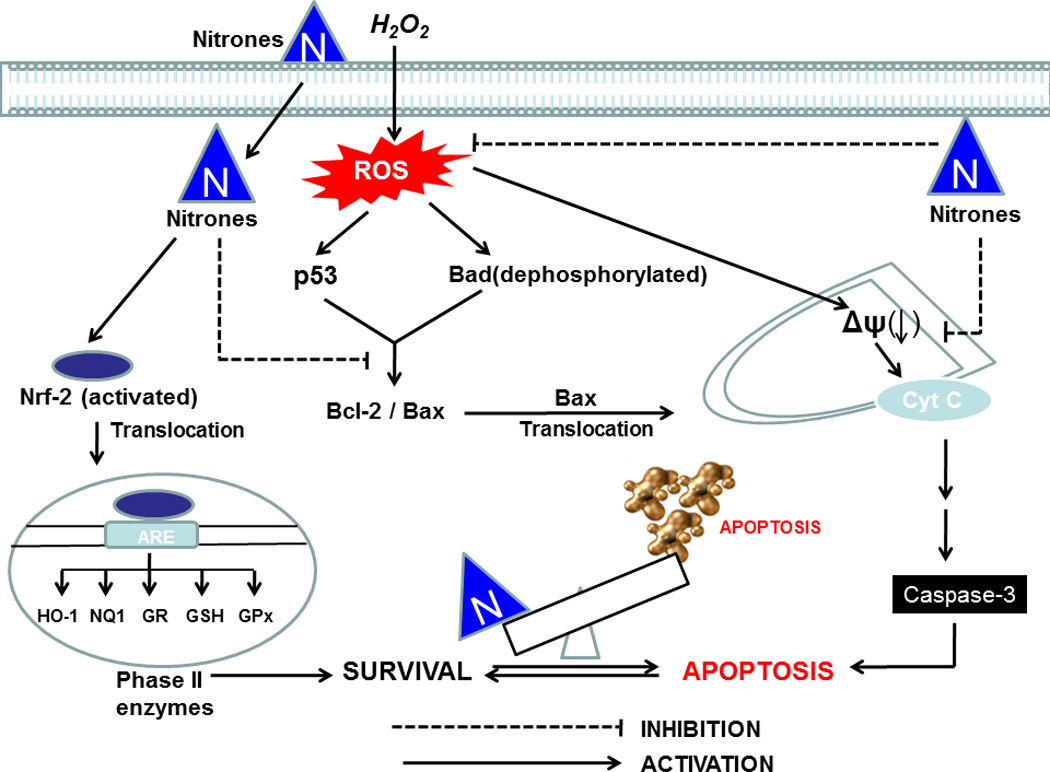

In conclusion, the present study clearly demonstrates that pretreatment of oxidatively challenged cells with nitrone results in the attenuation of H2O2-induced cytotoxicity and apoptosis. The underlining mechanisms of protective effects of nitrones are contributed to a combination of ROS-quenching, up-regulation of phase II enzymes via Nrf-2 activation and suppression of mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cascade (Fig. 9). This study also demonstrates for the first time that a number of endogenous antioxidants and phase II enzymes are induced by nitrones to suppress ROS-mediated endothelial damage. Future investigations will be necessary to determine the upstream molecular mechanisms as well as the in vivo relevance of our findings. Since oxidative stress-induced endothelial cell dysfunction plays a key role in cardiovascular diseases, our findings suggested a novel application for nitrone-therapeutics in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases or cardiometabolic disorders such as hypertension or hyperglycemia which are associated with endothelial dysfunction and depletion of cellular antioxidant pool.

Fig. 9.

Possible mechanism of nitrone-mediated cytoprotection against oxidative stress. In the schematic diagram activation pathways are indicated by (→), and the inhibitory pathways are indicated by (⊣).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant RO1 HL081248 to F.V and RO1HL075040 to A.I.D

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Amlan Das, Email: amlan.das@gmail.com.

Bhavani Gopalakrishnan, Email: bhavani.gopalakrishnan@osumc.edu.

Oliver H. Voss, Email: voss.39@buckeyemail.osu.edu.

Andrea I. Doseff, Email: doseff.1@osu.edu.

Frederick A. Villamena, Email: villamena.1@osu.edu.

References

- 1.Loukides S, Bakakos P, Kostikas K. Oxidative stress in patients with COPD. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:469–747. doi: 10.2174/138945011794751573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Domej W, Foldes-Papp Z, Flogel E, Haditsch B. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2006;7:117–123. doi: 10.2174/138920106776597676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciencewicki J, Trivedi S, Kleeberger SR. Oxidants and the pathogenesis of lung diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:456–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.004. quiz 69–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction in myocardial remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:449–456. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heistad DD, Wakisaka Y, Miller J, Chu Y, Pena-Silva R. Novel aspects of oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Circ J. 2009;73:201–207. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zweier JL, Talukder MA. The role of oxidants and free radicals in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayre LM, Perry G, Smith MA. Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:172–188. doi: 10.1021/tx700210j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Z, Zhao Y, Zhao B. Superoxide anion, uncoupling proteins and Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;46:187–194. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.09-104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreher D, Junod AF. Role of oxygen free radicals in cancer development. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munzel T, Gori T, Bruno RM, Taddei S. Is oxidative stress a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease? Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2741–2748. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chrissobolis S, Miller AA, Drummond GR, Kemp-Harper BK, Sobey CG. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in cerebrovascular disease. Front Biosci. 2011;16:1733–1745. doi: 10.2741/3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potenza MA, Gagliardi S, Nacci C, Carratu MR, Montagnani M. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: from mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:94–112. doi: 10.2174/092986709787002853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Haan JB, Cooper ME. Targeted antioxidant therapies in hyperglycemia-mediated endothelial dysfunction. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:709–729. doi: 10.2741/s182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaliora AC, Dedoussis GV, Schmidt H. Dietary antioxidants in preventing atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr A, Frei B. The role of natural antioxidants in preserving the biological activity of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1806–1814. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augustyniak A, Bartosz G, Cipak A, Duburs G, Horakova L, Luczaj W, et al. Natural and synthetic antioxidants: an updated overview. Free Radic Res. 44:1216–1262. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.508495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moosmann B, Behl C. Antioxidants as treatment for neurodegenerative disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11:1407–1435. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willcox BJ, Curb JD, Rodriguez BL. Antioxidants in cardiovascular health and disease: key lessons from epidemiologic studies. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:75D–86D. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2007;297:842–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomson MJ, Puntmann V, Kaski JC. Atherosclerosis and oxidant stress: the end of the road for antioxidant vitamin treatment? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21:195–210. doi: 10.1007/s10557-007-6027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown BG, Cheung MC, Lee AC, Zhao XQ, Chait A. Antioxidant vitamins and lipid therapy: end of a long romance? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1535–1546. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000034706.24149.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villamena FA, Zweier JL. Detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by EPR spin trapping. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:619–269. doi: 10.1089/152308604773934387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villamena FA, Das A, Nash KM. Potential implication of the chemical properties and bioactivity of nitrone spin traps for therapeutics. Future Med Chem. 2012;4 doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.74. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molnar M, Lennmyr F. Neuroprotection by S-PBN in hyperglycemic ischemic brain injury in rats. Ups J Med Sci. 2010;115:163–168. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2010.498592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuo L, Chen Y-R, Reyes LA, Lee H-L, Chen C-L, Villamena FA, et al. The radical trap 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide exerts dose-dependent protection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through preservation of mitochondrial electron transport. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:515–523. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.143479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandal MN, Moiseyev GP, Elliott MH, Kasus-Jacobi A, Li X, Chen H, et al. Alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN) prevents light-induced degeneration of the retina by inhibiting RPE65 protein isomerohydrolase activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32491–32501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Floyd RA, Hensley K, Bing G. Evidence for enhanced neuro-inflammatory processes in neurodegenerative diseases and the action of nitrones as potential therapeutics. Adv Res Neurodegener. 2000;8:387–414. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6301-6_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Floyd RA, Hensley K. Nitrone inhibition of age-associated oxidative damage. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;899:222–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Floyd RA, Chandru HK, He T, Towner R. Anti-cancer activity of nitrones and observations on mechanism of action. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:373–379. doi: 10.2174/187152011795677517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fong JJ, Rhoney DH. NXY-059: review of neuroprotective potential for acute stroke. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:461–471. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Floyd RA, Kopke RD, Choi C-H, Foster SB, Doblas S, Towner RA. Nitrones as therapeutics. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1361–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inanami O, Kuwabara M. alpha-Phenyl N-tert-butyl nitrone (PBN) increases the cortical cerebral blood flow by inhibiting the breakdown of nitric oxide in anesthetized rats. Free Radic Res. 1995;23:33–39. doi: 10.3109/10715769509064017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durand G, Prosak RA, Han Y, Ortial S, Rockenbauer A, Pucci B, et al. Spin trapping and cytoprotective properties of fluorinated amphiphilic carrier conjugates of cyclic versus linear nitrones. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1570–1581. doi: 10.1021/tx900114v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dehouck MP, Cecchelli R, Richard Green A, Renftel M, Lundquist S. In vitro blood-brain barrier permeability and cerebral endothelial cell uptake of the neuroprotective nitrone compound NXY-059 in normoxic, hypoxic and ischemic conditions. Brain Res. 2002;955:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S, de AVGV, Bouajila J, Dias AG, Cyrino FZ, Bouskela E, et al. Alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butyl nitrone (PBN) derivatives: synthesis and protective action against microvascular damages induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:3572–3578. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bian K, Doursout MF, Murad F. Vascular system: role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.06632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ignarro LJ, editor. Nitric Oxide: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Locigno EJ, Zweier JL, Villamena FA. Nitric oxide release from the unimolecular decomposition of the superoxide radical anion adduct of cyclic nitrones in aqueous medium. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:3220–3227. doi: 10.1039/b507530k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villamena FA. Superoxide radical anion adduct of 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide. 5. Thermodynamics and kinetics of unimolecular decomposition. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:6398–6403. doi: 10.1021/jp902269t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Favreau LV, Pickett CB. Transcriptional regulation of the rat NAD(P)H:quinone reductase gene. Identification of regulatory elements controlling basal level expression and inducible expression by planar aromatic compounds and phenolic antioxidants. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4556–4561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rushmore TH, Morton MR, Pickett CB. The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11632–11639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kong AN, Owuor E, Yu R, Hebbar V, Chen C, Hu R, et al. Induction of xenobiotic enzymes by the MAP kinase pathway and the antioxidant or electrophile response element (ARE/EpRE) Drug Metab Rev. 2001;33:255–271. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120000652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loboda A, Jazwa A, Grochot-Przeczek A, Rutkowski AJ, Cisowski J, Agarwal A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 and the vascular bed: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1767–1812. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu H, Zhang L, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Ross D, Trush MA, et al. Nrf2 controls bone marrow stromal cell susceptibility to oxidative and electrophilic stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joseph P, Long DJ, 2nd, Klein-Szanto AJ, Jaiswal AK. Role of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (DT diaphorase) in protection against quinone toxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andreadi CK, Howells LM, Atherfold PA, Manson MM. Involvement of Nrf2, p38, B-Raf, and nuclear factor-kappaB, but not phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, in induction of hemeoxygenase-1 by dietary polyphenols. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1033–1040. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balogun E, Hoque M, Gong P, Killeen E, Green CJ, Foresti R, et al. Curcumin activates the haem oxygenase-1 gene via regulation of Nrf2 and the antioxidant-responsive element. Biochem J. 2003;371:887–895. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hur KY, Kim SH, Choi MA, Williams DR, Lee YH, Kang SW, et al. Protective effects of magnesium lithospermate B against diabetic atherosclerosis via Nrf2-ARE-NQO1 transcriptional pathway. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakurai T, Kanayama M, Shibata T, Itoh K, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, et al. Ebselen, a seleno-organic antioxidant, as an electrophile. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:1196–1204. doi: 10.1021/tx0601105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giudice A, Arra C, Turco MC. Review of molecular mechanisms involved in the activation of the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway by chemopreventive agents. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;647:37–74. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-738-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alam J, Wicks C, Stewart D, Gong P, Touchard C, Otterbein S, et al. Mechanism of heme oxygenase-1 gene activation by cadmium in MCF-7 mammary epithelial cells. Role of p38 kinase and Nrf2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27694–27702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang KW, Lee SJ, Kim SG. Molecular mechanism of nrf2 activation by oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1664–1673. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rangasamy T, Guo J, Mitzner WA, Roman J, Singh A, Fryer AD, et al. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to severe airway inflammation and asthma in mice. J Exp Med. 2005;202:47–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thimmulappa RK, Scollick C, Traore K, Yates M, Trush MA, Liby KT, et al. Nrf2-dependent protection from LPS induced inflammatory response and mortality by CDDO-Imidazolide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:883–889. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Das A, Bhattacharya A, Chakrabarti G. Cigarette smoke extract induces disruption of structure and function of tubulin-microtubule in lung epithelium cells and in vitro. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:446–459. doi: 10.1021/tx8002142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Das A, Chakrabarty S, Choudhury D, Chakrabarti G. 1,4-Benzoquinone (PBQ) induced toxicity in lung epithelial cells is mediated by the disruption of the microtubule network and activation of caspase-3. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1054–1066. doi: 10.1021/tx1000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chakrabarty S, Das A, Bhattacharya A, Chakrabarti G. Theaflavins depolymerize microtubule network through tubulin binding and cause apoptosis of cervical carcinoma HeLa cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:2040–2048. doi: 10.1021/jf104231b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voss OH, Kim S, Wewers MD, Doseff AI. Regulation of monocyte apoptosis by the protein kinase Cdelta-dependent phosphorylation of caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17371–17379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naughton P, Foresti R, Bains SK, Hoque M, Green CJ, Motterlini R. Induction of heme oxygenase 1 by nitrosative stress. A role for nitroxyl anion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40666–40674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Villamena FA. Superoxide radical anion adduct of 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide. 6. Redox properties. J Phys Chem A. 2010;114:1153–1160. doi: 10.1021/jp909614u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Villamena FA, Hadad CM, Zweier JL. Comparative DFT study of the spin trapping of methyl, mercapto, hydroperoxy, superoxide, and nitric oxide radicals by various substituted cyclic nitrones. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:1662–1674. doi: 10.1021/jp0451492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Villamena FA, Locigno EJ, Rockenbauer A, Hadad CM, Zweier JL. Theoretical and experimental studies of the spin trapping of inorganic radicals by 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). 1. Carbon dioxide radical anion. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:13253–13258. doi: 10.1021/jp064892m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Villamena FA, Locigno EJ, Rockenbauer A, Hadad CM, Zweier JL. Theoretical and experimental studies of the spin trapping of inorganic radicals by 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). 2. Carbonate radical anion. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:384–391. doi: 10.1021/jp065692d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burgett RA, Bao X, Villamena FA. Superoxide radical anion adduct of 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). 3. Effect of mildly acidic pH on the thermodynamics and kinetics of adduct formation. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:2447–2455. doi: 10.1021/jp7107158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bradamante S, Monti E, Paracchini L, Lazzarini E, Piccinini F. Protective activity of the spin trap tert-butyl-alpha-phenyl nitrone (PBN) in reperfused rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1992;24:375–386. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)93192-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tosaki A, Haseloff RF, Hellegouarch A, Schoenheit K, Martin VV, Das DK, et al. Does the antiarrhythmic effect of DMPO originate from its oxygen radical trapping property or the structure of the molecule itself? Basic Res Cardiol. 1992;87:536–547. doi: 10.1007/BF00788664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang PGCT, Taniguchi N, editors. Nitric Oxide Donors. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryter SW, Kim HP, Hoetzel A, Park JW, Nakahira K, Wang X, et al. Mechanisms of cell death in oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:49–89. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ravindran J, Gupta N, Agrawal M, Bala Bhaskar AS, Lakshmana Rao PV. Modulation of ROS/MAPK signaling pathways by okadaic acid leads to cell death via, mitochondrial mediated caspase-dependent mechanism. Apoptosis. 2011;16:145–161. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, et al. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.del Peso L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu B, Chen Y, St Clair DK. ROS and p53: a versatile partnership. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1529–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Droin NM, Newmeyer DD, Schuler M, et al. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Durand G, Choteau F, Pucci B, Villamena FA. Reactivity of superoxide radical anion and hydroperoxyl radical with alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN) derivatives. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:12498–12509. doi: 10.1021/jp804929d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cova D, De Angelis L, Monti E, Piccinini F. Subcellular distribution of two spin trapping agents in rat heart: possible explanation for their different protective effects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;15:353–360. doi: 10.3109/10715769209049151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Durand G, Poeggeler B, Ortial S, Polidori A, Villamena FA, Boker J, et al. Amphiphilic amide nitrones: A new class of protective agents acting as modifiers of mitochondrial metabolism. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4849–4861. doi: 10.1021/jm100212x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Durand G, Polidori A, Salles JP, Pucci B. Synthesis of a new family of glycolipidic nitrones as potential antioxidant drugs for neurodegenerative disorders. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:859–862. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)01079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Han Y, Liu Y, Rockenbauer A, Zweier JL, Durand G, Villamena FA. Lipophilic beta-cyclodextrin cyclic-nitrone conjugate: synthesis and spin trapping studies. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5369–5380. doi: 10.1021/jo900856x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kizhakekuttu TJ, Widlansky ME. Natural antioxidants and hypertension: promise and challenges. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28:e20–e32. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shay KP, Moreau RF, Smith EJ, Smith AR, Hagen TM. Alpha-lipoic acid as a dietary supplement: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1149–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]