Abstract

Tinnitus, the perception of a phantom sound, is a common consequence of damage to the auditory periphery. A major goal of tinnitus research is to find the loci of the neural changes that underlie the disorder. Crucial to this endeavor has been the development of an animal behavioral model of tinnitus, so that neural changes can be correlated with behavioral evidence of tinnitus. Three major lines of evidence implicate the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN) in tinnitus. First, elevated spontaneous activity in the DCN is correlated with peripheral damage and tinnitus. Second, there are somatosensory inputs to the DCN that can modulate spontaneous activity and might mediate the somatic-auditory interactions seen in tinnitus patients. Third, we have found a subpopulation of DCN neurons in the adult rat that express doublecortin, a plasticity-related protein. The expression of this protein may reflect a role of these neurons in the neural reorganization causing tinnitus. However, there is a problem in extending the findings in the rodent DCN to humans. Classic studies state that the structure of the primate DCN is quite different from that of rodents, with primates lacking granule cells, the recipients of somatosensory input. To address the possibility of major species differences in DCN organization, we compared Nissl-stained sections of the DCN in five different species. In contrast to earlier reports, our data suggest that the organization of the primate DCN is not dramatically different from that of the rodents, and validate the use of animal data in the study of tinnitus.

Keywords: granule cells, unipolar brush cells, fusiform cells, cartwheel cells, inferior colliculus, somatic tinnitus

1. The problem of tinnitus

Tinnitus, the perception of a phantom sound, is a common correlate of damage to the auditory periphery, either to receptor cells or to neurons of the spiral ganglion. Damage can result from aging (Nicolas-Puel et al., 2002) or exposure to noise, the cancer drugs carboplatin and cisplatin (Ding et al., 1999; Godfrey et al., 2005; Hofstetter et al., 1997; Husain et al., 2001; Klis et al., 2002; Stengs et al., 1998), styrene (Chen et al., 2008) or other agents. Systemic administration of the drug salicylate can induce temporary tinnitus (Stolzberg et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2007). Tinnitus is thought to result from plastic reorganization in the central processing of auditory information triggered by these manipulations (reviews in Kaltenbach, 2011; Roberts et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011b). Many studies have sought to discover the loci and mechanisms of this reorganization, and to tease out which changes are simply correlates of peripheral damage and which are the critical determinants of tinnitus.

Discovery of the neural correlates of tinnitus must contend with a major obstacle in that tinnitus as a perception is most readily assessed in humans, but the investigation of neural mechanisms in humans is limited to imaging studies and relatively gross electrophysiological measures (review and references in Adjamian et al., 2009; Schaette and McAlpine, 2011). On the other hand, in animals it is relatively easy to assess the electrophysiological or neuroanatomical changes that follow peripheral auditory damage, but it is much more difficult to see how these changes relate to the perception of tinnitus. Several behavioral animal models of tinnitus have been devised to allow a more direct correlation of tinnitus and neural changes.

2. What is the neural basis of tinnitus?

Investigations of the neural correlates of tinnitus in animals have looked for electrophysiological, anatomical or neurochemical alterations subsequent to peripheral damage. Multiple sites along the auditory pathways have been implicated in tinnitus including the dorsal (DCN) and ventral (VCN) cochlear nuclei (Brozoski et al., 2002; Dehmel et al., 2012; Kaltenbach and Afman, 2000; Kaltenbach et al., 2000; Kaltenbach et al., 2002; Kraus et al., 2009a; Middleton et al., 2011; Rachel et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2010; Zacharek et al., 2002), the inferior colliculus (Abbott et al., 1999; Bancroft et al., 1991; Basta and Ernest, 2004; Bauer et al., 2008; Burkard et al., 1997; Chen and Jastreboff, 1995; Dong et al., 2010; Jastreboff and Sasaki, 1986; Kazee et al., 1995; McFadden et al., 1998; Milbrandt et al., 2000; Salvi et al., 1990; Wang et al., 2008; Wang et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2002a; Wang et al., 2002b) and the auditory cortex (Liu et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2011; Mühlnickel et al., 1998; Ortmann et al., 2011; Stolzberg et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2007). More recently, neural changes correlated with hearing loss and tinnitus have been recognized in structures outside the classical auditory pathways, most notably the hippocampus and limbic system, (Kraus et al., 2010; Leaver et al., 2011; Muhlau et al., 2006; Rauschecker et al., 2010). In this review, we will focus on the DCN as a possible site of tinnitus generation, since data from many studies suggest that the DCN undergoes neuroplastic reorganization following cochlear damage and that these changes correlate with behavioral evidence of tinnitus (Brozoski et al., 2002; Brozoski and Bauer, 2005; Dehmel et al., 2012; Jastreboff et al., 1988; Jastreboff and Sasaki, 1994; Kaltenbach, 2006a; Lobarinas et al., 2004; Turner et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2007). We will briefly summarize the anatomical organization of the DCN and then review the evidence for its role in tinnitus. We will then ask how applicable the results of these studies in rodents are to humans.

3. The DCN: laminar and cellular organization

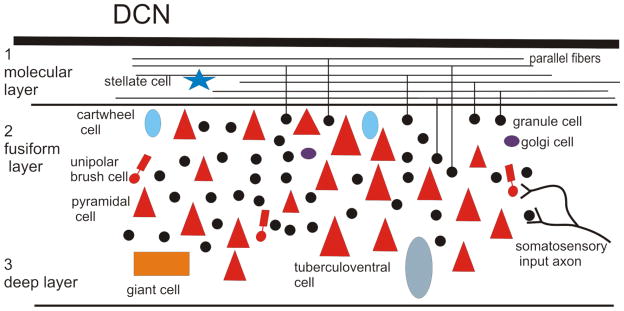

The classic studies of DCN laminar and cellular organization were done in the cat (Brawer et al., 1974; Lorente de No, 1933; Osen, 1969). In that animal, the DCN is a distinctly laminar structure; the layers are easily recognized in Nissl sections. Laminar structure of the DCN is also seen in other animals used in auditory research. However, there are differences among authors regarding how many layers are recognized (3–5 in different studies, e.g. 4 layers in Hackney et al., 1990; Willard and Ryugo, 1983, mouse and gunea pig,) and whether they are referred to by name or by number. The most common scheme divides the DCN into three layers (see the review of Oertel and Young, 2004). The outermost is the molecular layer (layer 1). Next is the fusiform or pyramidal layer (layer 2), and the deepest is the polymorphic or deep layer (layer 3). There are different cell types with distinct morphologies and connections in each layer. There are four classes of glutamatergic excitatory neurons, the granule cells (layer 2), the fusiform cells (layer 2, also called pyramidal, large bipolar or principal neurons, see Blackstad et al., 1984), the unipolar brush cells (UBCs, layer 2) and the giant cells (layer 3). There are differences among studies in the description of the layer 2 projection neurons. Oertel and Young (2004) use the term “fusiform cells” and show these neurons as having elongated somata with a radial orientation. While this is true in the cat, studies in other animals have described the large cells in layer 2 as pyramidal (e.g. Mugnaini et al., 1980) or multipolar (e.g. Willard and Ryugo, 1983). There also several classes of inhibitory interneurons, Golgi cells (layer 2, GABAergic), stellate cells (layer 1, GABAergic), tuberculoventral cells (layer 3, glycinergic) and cartwheel cells (layer 2, glycinergic). In addition to the types shown by Oertel and Young (2004), there is at least one additional rare cell type, the Purkinje-like cell, PLC (Hurd and Feldman, 1994; Koszeghy et al., 2009; Spatz, 1997; Spatz, 2003; Webster and Trune, 1982).

The fusiform/pyramidal cells, the projection neurons of the DCN, send their axons to the inferior colliculus, a relay nucleus in the auditory pathway (review in Cant and Benson, 2003). Oertel and Young (2004) also summarize the basic DCN circuitry: the fusiform cells receive auditory input on their basal dendrites, and nonauditory input on their apical dendrites via the axons of the granule cells (the parallel fibers). They are inhibited by cartwheel cells, stellate cells and tuberculoventral cells. The search for changes in the DCN that might correlate with tinnitus has focused on the responses of the fusiform/pyramidal projection neurons since abnormal neural activity underlying perception presumably must be relayed to more central levels of the system. Figure 1 summarizes the laminar organization and cell types of the DCN based on data from the rat, one of the most widely used species in tinnitus research.

Figure 1.

Laminar and cellular organization of the DCN, based on Nissl-stained sections in the rat. Only somata are represented. Stellate, cartwheel, and Golgi cells are inhibitory interneurons. Granule cells are the source of the excitatory parallel fibers in the molecular layer (1). The giant cells, tuberculoventral cells and pyramidal cells are excitatory projection neurons, and the unipolar brush cells are excitatory interneurons.

4. Physiological correlate of tinnitus: hyperactivity in the DCN

Physiological changes occur in the DCN with interventions that can result in tinnitus, leading to the hypothesis that the DCN is a key structure in its generation. The DCN fusiform/pyramidal cells become spontaneously hyperactive in animals with behavioral evidence of tinnitus (Brozoski et al., 2002; Brozoski and Bauer, 2005; Kaltenbach, 2006b; Kaltenbach, 2007; Kaltenbach and Godfrey, 2008; reviewed in Tzounopoulos, 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011b; Zhang et al., 2006). The increase in spontaneous activity occurs in neurons tuned to frequencies associated with the behaviorally measured tinnitus pitch, again suggesting a direct relation between the increased neural activity and tinnitus generation. These results are generally interpreted as reflecting a decreased effectiveness of inhibitory mechanisms in tinnitus, but recent evidence shows that there is also evidence an increase in excitatory input (Dehmel et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2009). Evidence for decreased expression of glycinergic receptors has been found (Wang et al., 2009; review in Wang et al., 2011b). However, direct application of salicylate (a treatment which is known to cause tinnitus if given systemically) onto brain slices of the DCN, causes a decreased firing rate in fusiform cells (Wei et al., 2010). These data argue against the idea that salicylate induces tinnitus by directly affecting inhibitory neurons, but the results in a brain slice may not fully reflect systemic effects.

5. DCN as the site of somatosensory modulation of tinnitus

The second body of evidence supporting a role of the DCN in tinnitus is based on clinical observations. In some patients, tinnitus can be modulated by somatosensory stimuli or voluntary movement, suggesting an interaction between auditory and somatosensory systems (Levine, 1999; Levine et al., 2003; Pinchoff et al., 1998; Shore et al., 2007; Simmons et al., 2008). The DCN is a uniquely suited candidate site for such multisensory interactions (review in Levine, 1999). There is somatosensory input to the DCN, carried by mossy fibers that synapse on granule cells and on unipolar brush cells (Davis et al., 1996; Dehmel et al., 2008; El-Kashlan and Shore, 2004; Koehler et al., 2011; Oertel and Young, 2004; Shore et al., 2007; Shore et al., 2000; Zeng et al., 2009; Zhou and Shore, 2004; Zhou et al., 2007). There is also evidence of changes in auditory-somatosensory interactions after interventions that could induce tinnitus (Dehmel et al., 2012; Shore et al., 2008). These data support the idea of a critical role for the DCN in mediating auditory-somatosensory interactions.

6. Novel plasticity in the DCN: DCX- expression in unipolar brush cells in the adult rat

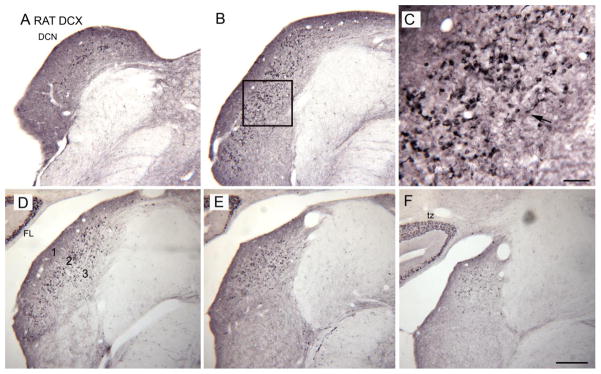

We have recently found evidence for a previously unknown form of plasticity in one DCN cell class, the unipolar brush cell (Manohar et al., 2012). This plasticity has the potential to affect the auditory-somatosensory interactions that are anatomically indicated to occur in the DCN. UBCs are excitatory interneurons; they have been extensively studied by Mugnaini and colleagues (review in Mugnaini et al., 2011). UBCs are found in the DCN and also in the cerebellum, another region recently implicated in tinnitus (Brozoski et al., 2007). The UBC is the only type of cerebellar interneuron that is not evenly distributed over the entire cerebellar cortex; they are found most densely in the vestibulocerebellum. In the DCN, the UBCs are geographically distributed with the granule cell system (Diño and Mugnaini, 2008). They receive input from mossy fibers carrying nonauditory signals (Fig. 1). The axons of UBCs form excitatory synapses on granule cells and on other UBCs (Diño and Mugnaini, 2008), and therefore can provide local amplification of signals (Diño et al., 2000). We found a population of UBCs in the DCN and vestibulocerebellum of the adult rat that express the protein doublecortin (DCX). DCX is expressed in newly- born cells that differentiate into neurons, and in migrating neurons for about 15 after cell birth (Francis et al., 1999; Gleeson et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2008). Figure 2(A, B, D–F) shows DCX expression on transverse sections over the rostro-caudal extent of the DCN of an adult rat. Figure 2C shows a higher magnification image of the DCX-immunoreactive (DCX-ir) elements, showing that they are UBCs (example at arrow). Figure 2F also shows that there are DCX-ir UBCs in the region between the ventral paraflocculus and flocculus of the cerebellum, a region called the “transition zone” (tz) (Floris et al., 1994).

Figure 2.

A, B, D– F. DCX expression in the DCN on five sections about 250 μm apart. A is the most caudal section. C. The DCX-ir profiles are UBCs. The arrow indicates one example in which the soma and brush are both visible in the plane of section.

There are two possible interpretations of these results. One possibility is that there is adult neurogenesis of UBCs in the adult and that these new cells become integrated into functional circuits as is true in other areas of adult neurogenesis, the hippocampus and subventricular zone (Dayer et al., 2003; Gould et al., 1991; Kaplan et al., 1985; Kempermann et al., 1998; Petreanu and Alvarez-Buylla, 2002; Winner et al., 2002). The other possibility is that the DCX-ir UBCs are mature neurons that have retained the capacity for synaptic plasticity, and that DCX expression is a reflection of that plastic capability. Whether they are newly generated or not, the DCX-ir UBCs may have some crucial role in mediating plasticity in the integration of auditory and nonauditory signals or in other plastic changes in the DCN that occur with tinnitus.

7. Organization of the primate DCN: implications for its role in tinnitus

There are behavioral and electrophysiological data in rodents that strongly support the idea that the DCN is critical in the generation of tinnitus. However, the goal of these studies in animals is to illuminate the mechanisms of tinnitus in humans. A significant challenge to that goal is presented by studies suggesting that the anatomical organization of the DCN may be radically different in primates than in rodents. The major differences that have been reported are an absence of laminar structure and an absence of granule cells. This view is widely accepted. For example, Webster (1992) states that “The human DCN, although large, appears degenerate and disorganized.... lacks the usual laminar structure and many of the cell types….” Similarly, Malmierca (2003) describes the DCN as “nonlaminated in humans.” Crosby et al. (Crosby et al., 1962) present a slightly more complex picture stating that “an indistinct layering is sometime seen in the human dorsal cochlear nucleus whereas in other instances no lamination is present.”

If the human DCN does indeed lack lamination and granule cells, the DCN substrate for auditory-somatosensory interactions would also be absent. In that case, the DCN could not be the site of auditory-somatosensory interactions in tinnitus. This would call into question the applicability of rodent models. There are, however, some more recent data suggesting that the primate DCN may not be so different after all. Since the issue of species differences in DCN organization is critical for the clinical relevance to tinnitus based on data from animal experiments, we will consider the evidence supporting and opposing the idea that the composition of the primate DCN is qualitatively different from what is seen in other mammals. We will also illustrate the organization of the DCN in five species using Nissl and immunostained sections.

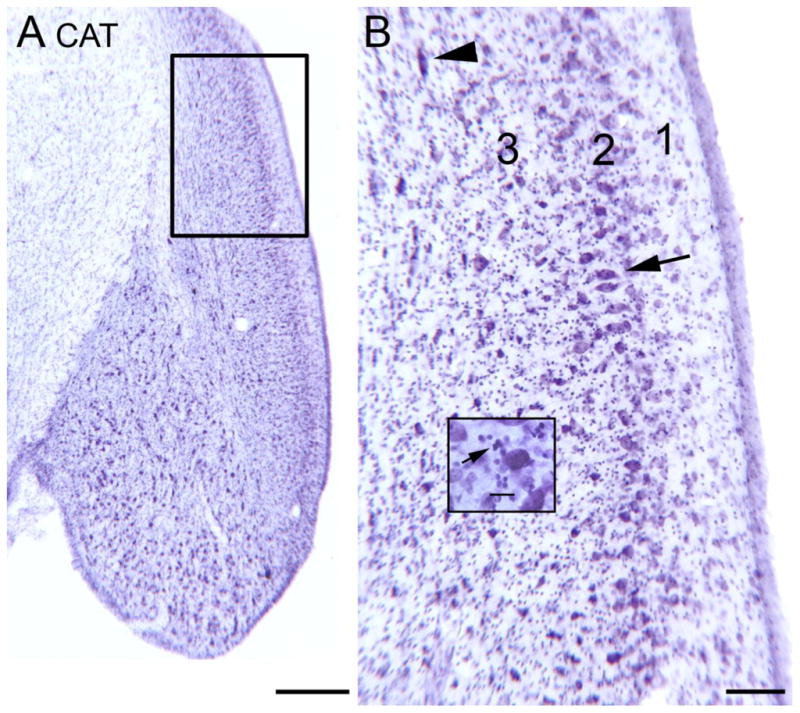

8. The DCN in the cat

Many early studies in the auditory system, both anatomical and physiological, used the cat (some examples…Aitkin and Phillips, 1984; Aitkin et al., 1985; Brawer et al., 1974; Godfrey et al., 1975a; Godfrey et al., 1975b; Imig et al., 1972; Imig and Weinberger, 1973; Imig and Adrian, 1977; Osen, 1969) and its DCN organization became the standard to which other species were compared. Figure 3A shows a cresyl violet (CV)-stained section through the cochlear nuclei of a cat. The laminar organization of the DCN is apparent even at low magnification. Figure 3B is a higher magnification image showing the molecular layer (1), the fusiform/pyramidal layer (2) and the deep (polymorphic) layer (3). The arrow indicates a row of fusiform/pyramidal cells. While several neurons at the arrow do have elongated somata and are oriented radially, there are other somata in that layer that are more pyramidal than fusiform in shape. There is a very distinct fusiform cell layer with minimal dispersion of the fusiform/pyramidal cells. The arrowhead indicates a cell with a large horizontally-oriented soma in the deep layer. The inset shows the very small granule cells (examples at arrow). The organization of the cat DCN then closely resembles the summary schematic shown by Oertel and Young (2004, Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

The DCN in the cat shown on a CV-stained section. A. Low magnification image; note the laminar appearance. The rectangle shows the area in the larger image in B. Scale bar = 500 μm B. Laminar organization of cat DCN. There is much lighter staining in the outer or molecular layer (1). The arrow indicates a group of neurons in the fusiform/pyramidal cell layer (2) with elongated cell bodies oriented perpendicular to the surface. The arrowhead shows a cell in the polymorphic (3) layer with an elongated cell body. Scale bar =100 μm. The inset shows small, darkly labeled profiles, at arrow. Scale bar in inset = 0 μm.

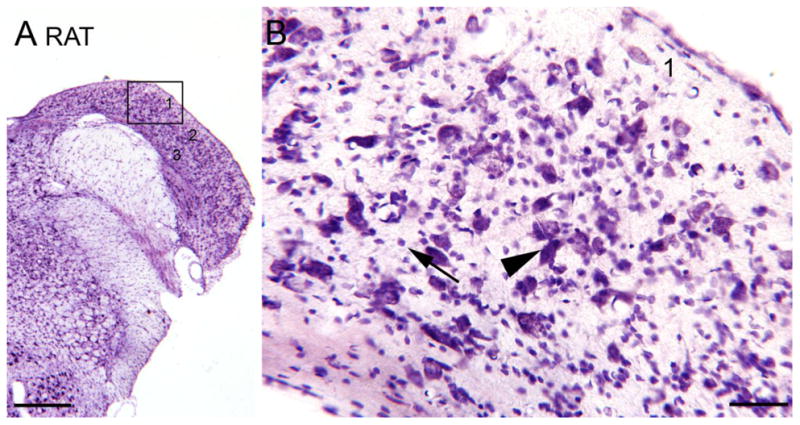

9. The rat

In recent years, the rat has become a more popular experimental subject, especially in the development of an animal model of tinnitus (Jastreboff and Sasaki, 1994; Lobarinas et al., 2004; Turner et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009). It is generally assumed that DCN organization in the rat is similar to the cat. For example, Webster et al. (1992) write “In most mammals the DCN is a laminated structure,” but they reference Osen’s 1969 paper on the cat. Figure 3A shows a photomicrograph of a CV-stained section through the DCN of a Sprague Dawley rat. Comparing Figure 3A (cat) and Figure 4A (rat) shows that the laminar organization in the rat DCN is less well-defined in rat than in the cat. A molecular layer (layer 1) with fewer stained somata is clearly visible, but there is no distinct band of aligned, large fusiform somata in the rat (layer 2) as there is in the cat. Instead the large somata are scattered over about 300 μm. This impression is confirmed by examination of the higher magnification image (Fig. 4B). The arrowhead shows an example of a neuron with a large, fusiform soma that is radially oriented. However, there are other large somata found at many other orientations and that are more pyramidal than fusiform in shape. They are also more widely dispersed than the fusiform cells in the cat. Granule cells are seen scattered over the whole width of the DCN (example at Fig. 4B, arrow). This is not a new observation, a lack of a distinct laminar organization in rat DCN has been noted previously by Mugnaini et al. (1980), who wrote “In the rat the DCN is, as a whole, laminated less distinctly…” In the mouse, Willard and Ryugo (1983) recognized a laminar organization of the mouse DCN but their data do not show (see their Fig. 7–6) a systematic radial orientation of large fusiform cells. Both the rat and the mouse, then, share with the cat a laminar organization of the DCN, but both rodents differ from the cat in lacking a distinct layer 2 comprised of a row of radially-oriented fusiform cells.

Figure 4.

The DCN in the rat, CV staining. A. Low magnification image. The rectangle shows the location of the higher magnification image in B. Scale bar = 500 μm. B. 1, 2, 3, indicate the layers. The arrowhead shows a large cell with fusiform cell body oriented perpendicular to the surface. The arrow shows small neurons.

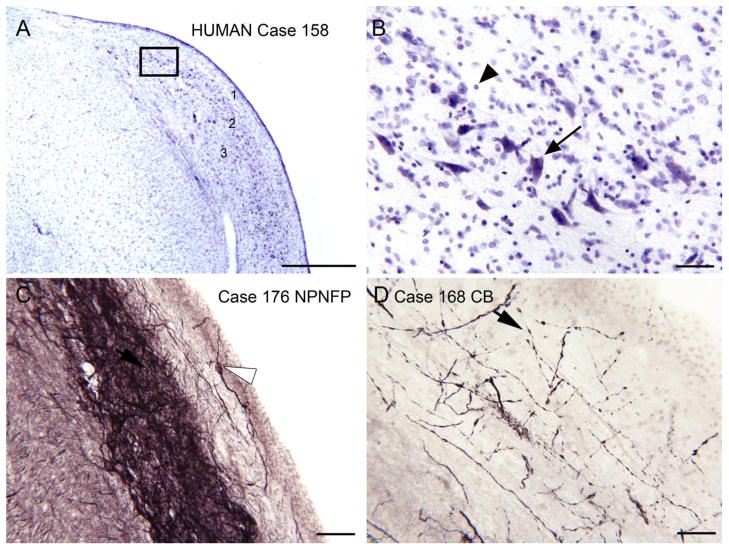

Figure 7.

The DCN in the human. A. CV staining. There is an outer layer (1) with few stained somata, a darker band below it (2) with scattered, stained, large somata, and lighter staining and more scattered profiles deep to that (3). The boxed region is shown at higher magnification in B. Scale bar=1 mm. B. Large stained profiles; somata are elongated but not all oriented the same way. Note the many small stained somata (arrowhead). Scale bar=50 μm. C. Laminar organization as shown by label with an antibody to nonphosphorylated neurofilament protein (NPNFP). There is a darkly stained band made up of somata (example at arrow) and a dense meshwork of stained processes. In layer 1 there one stained neuron and a few stained fibers (example at arrowhead). Scale bar=50 μm. D. Calbindin (CB)-immunoreactivity in fine, beaded fibers (example at arrowhead) that overlap layer 2. Scale bar= 50 μm.

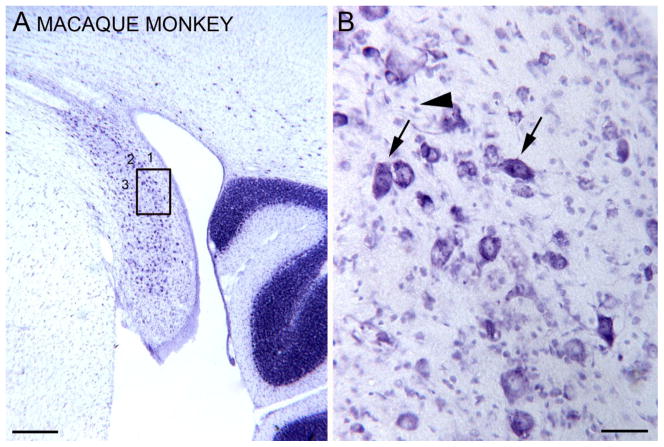

Figure 6.

The DCN in the macaque monkey, CV staining. A. Laminar organization (three layers, 1, 2, and 3 can be distinguished) is visible at low magnification. The rectangle shows the location of the higher magnification image in B. Scale bar=500 μm. B. Image through the fusiform/pyramidal cell layer (2). The arrows indicate the elongated somata of larger neurons oriented at different angles. The arrowhead indicates two small profiles. Scale bar=50 μm.

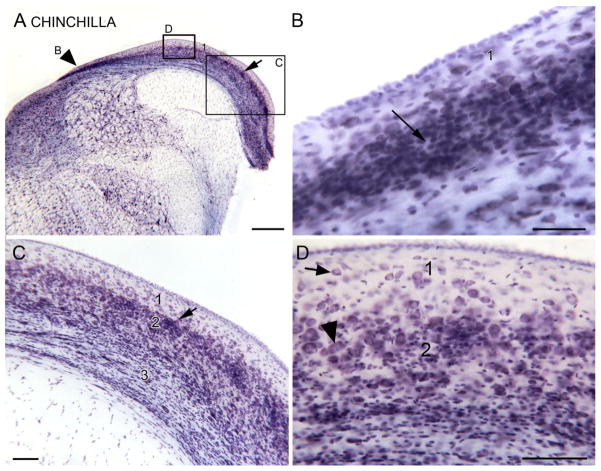

10. The chinchilla

Are differences in the appearance of layer 2 between mice and rats and the cat found in all rodents? We also looked at the organization of the DCN in the chinchilla, another rodent used in auditory research (a few examples…Hamernik et al., 1987; Henderson et al., 1983; Salvi et al., 1978; Salvi et al., 1982a; Salvi et al., 1982b; Salvi et al., 1990; Saunders et al., 1987; Zhou et al., 2009). Results in this animal also support a role of the DCN in tinnitus, since physiological evidence of tinnitus was obtained in the DCN of chinchillas that also had behavioral evidence (Brozoski et al., 2002). The rat and the chinchilla are only distant relatives. The chinchilla is a New World rodent, and a member of the suborder Hysticognathi, whereas the rat is an Old World rodent and a member of a different suborder, Myomorpha. Figure 5A shows a CV-stained section of the DCN in the chinchilla. The DCN is quite different in appearance than that of the mouse, rat or cat. The first striking feature is a band of darker staining at the medial edge of the DCN (Fig. 5A, arrowhead). The higher magnification image of this region (Fig. 5B) shows that it is composed of many densely packed and darkly stained granule cells. This region resembles the “external granular layer” described in some New World primates (e.g. galago, Fig. 2; marmoset, Fig. 1, in Moore, 1980). More laterally along the DCN there are patches of granule cells (Fig. 5C, arrow). There are a few neurons in the molecular layer (Fig. 5D, arrow) and a band of larger cells that may define a pyramidal cell layer (Fig. 5D, arrowhead), but those cells are not arranged in a single row and do not have fusiform somata. There are thus some similarities between the chinchilla and New World primate species in the addition of a new external granular layer. The band of granule cells at the dorsal DCN is reminiscent of an observation in the chimpanzee, namely a concentration of granule cells caudally near the dorsolateral edge of the DCN (Heiman-Patterson and Strominger, 1985). However, the organization of the chinchilla DCN is quite different from that of either the cat, a carnivore, or the rat, another rodent.

Figure 5.

The DCN in the chinchilla, CV staining. A. Low magnification image of the DCN. The arrowhead on the left indicates a dense band of darkly stained small cells and is an alignment point for the higher magnification image in Fig. 4B. Scale bar = 500 μm. B. Dense band of stained granule cells, examples at arrow. Scale bar = 50 μm.

The guinea pig is another New World rodent species that has been used in auditory and tinnitus research (some examples include Klis et al., 2002; Stengs et al., 1998; Vass et al., 1998; Zeng et al., 2009; Zhou and Shore, 2004). It resembles the chinchilla in having marked laminar organization of the DCN. For layer 2, (referred to as the pyramidal-granule cell layer), Hackney et al. (1990) described a “series of large elongated cells with long axis arranged perpendicular to the ependymal surface”, a pattern closer to the cat than to the rat.

11. The macaque monkey

Rather surprisingly, from Nissl sections, the monkey DCN appears to be more distinctly laminated than the rat DCN. Figure 6A shows the DCN of a macaque monkey on a CV-stained section. A more lightly stained outer layer (1) and a more darkly stained band comprised of large somata (layer 2) are readily apparent. Figure 6B shows a higher magnification image of the large somata; many are elongated (examples at arrows) but they are not oriented parallel to each other as in the cat. There are smaller stained profiles (example at arrowhead) that are likely granule cells. These images show that an outer molecular layer and a fusiform/pyramidal cell layer are present in macaque monkey, and that its laminar organization while less distinct than the cat is actually more distinct than that of the rat. These observations are in agreement with Heiman and Strominger (1985) who noted that “the uniform radial orientation of pyramidal cells perpendicular to the surface that delimits as well as characterizes the pyramidal layer of cats is not a feature of DC in primates. In primates the long axes of the pyramidal cells are variably oriented with respect to the epithelium; only rarely are they perpendicular.” In this respect, the monkey actually resembles the rat, and both are dissimilar to the cat.

Earlier studies reported species differences in DCN organization. Moskowitz (1969) examined the DCN in 7 primate species. He found that the laminar organization and radial orientation of fusiform cells varied among species, with a very clear fusiform layer in tree shrews and to a lesser extent in bush babies and marmosets, whereas fusiform cells were randomly distributed in the gibbon. Moore (1980) also compared DCN organization in a number of nonhuman primate species, both Old World and New World monkeys. She found that there are differences in organization among primates, with a tendency toward geographic separation of granule cells and fusiform cells. In some species granule cells are found more superficially in a new “external granular layer” (Fig. 1 in Moore, 1980), and fusiform cells found more deeply in the DCN. The other major difference was dissimilarity in the number of granule cells in different primate species, with none at all found in the gibbon. While the paper argued for loss of DCN lamination and granule cells as “a phylogenetic trend,” the evolutionary scatter of the species studied does not support that conclusion. Instead, the data show that there is variation among primates in the geographic location of granule cells and fusiform/pyramidal cells. Another study clearly does show a laminar organization in the macaque monkey DCN (Fig. 3D in Heiman-Patterson and Strominger, 1985). There are also recent studies in monkeys that challenge the view that the primate DCN is different from that of rodent and cat. Moore et al. (1996) reported lamination of the baboon DCN and identified granule cells, stellate cells, Golgi cells and cartwheel cells on the basis of immunoreactivity to glycine or GABA. They did claim that granule cells were less numerous than in nonprimate species, but this claim was not substantiated by systematic stereologically based counts of cells. Rubio (2008) studied macaque DCN using immunohistochemical techniques. Her data provided evidence for lamination of the DCN including a molecular layer as well as evidence for a population of granule cells.

12. The human

The idea that the human DCN is unlaminated and lacks granule cells is actually based on very few studies (Adams, 1986; Heiman-Patterson and Strominger, 1985; Moore and Osen, 1979). There are many technical problems that can affect the quality of staining in human material, including the medical state of the person at death, the PMI (postmortem interval, time from death to immersion of the tissue in fixative) and the total time in fixative. There are also differences in staining quality among different Nissl stains. That technical issues may have been a factor in the human studies is reflected in the disagreement among the human studies. Moore and Osen (1979) concluded that human DCN lacks the lamination typical of other mammals and has only very few granule cells. They did describe fusiform or bipolar cells but noted that these were not radially arranged. Adams (1986), using only a Golgi stain, found even more differences in humans, with three major cell types, the granule cells, the cartwheel cells and the fusiform cells absent altogether. Heiman-Patterson and Strominger (1985) did see a molecular layer in the human but found only “scant” granule cells. They recognized several classes of cells in the adult human that they described as “giant, multipolar, pyramidal, and small”. How these equate to the cell types summarized by Oertel and Young (2004) is not clear.

More recent studies also support a greater diversity of cell types in the human. Spatz (2001) using immunohistochemistry identified UBCs in the human DCN. Since UBCs are found in association with granule cells (Diño et al., 2000; Diño and Mugnaini, 2008; Oertel and Young, 2004), their presence suggests that there is also a granule cell system in the human. Wagoner and Kulesza (2009) again using immunohistochemistry saw a tri-laminar organization of the human DCN, with an external molecular layer containing axons running parallel to the pial surface, an internal granular layer with a population of small round granule cells, and a deeper layer. They also distinguished five cell types, granule cells and four additional cell types called “round, elongate, stellate and giant cells” (Table 1, Wagoner and Kulesza, 2009). The large fusiform neurons at the interface between the molecular and granule cell layers were argued to correspond to the pyramidal/fusiform cells described in the cat. It is again not clear, however, which of the other cells might correspond to the cell types described in other mammals. These studies however, suggest that the human DCN is not as impoverished in organization or diversity of cell types as the generally accepted view (e.g. Webster, 1992).

Table 1.

Human Cases.

| Case | Gender | Age | PMI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 158 | M | 51 | 1 hr |

| 168 | M | 69 | 3 hrs |

| 176 | W | 71 | 3 hrs |

Our analysis of the DCN in humans supports both laminar organization and the existence of granule cells. Figure 7A shows a CV-stained section through the human DCN. An outer, lighter layer (1), a middle layer with larger somata (2) and a deeper layer with scattered stained cells (3) can be seen even at low magnification. Figure 7B shows a higher magnification image of the larger stained profiles. While some are elongated, they are not all oriented parallel to each other. There are also many stained smaller somata. These results show a laminar organization that is similar to that of other species. We have also begun studying the neurochemical organization of the human DCN using immunoreactivity to different markers that have been useful in understanding the organization of other brainstem structures (Baizer et al., 2007; Baizer and Broussard, 2010; Baizer et al., 2011). Figure 7C shows expression of nonphosphorylated neurofilament protein (NPNFP, “SMI32” antibody) in the DCN. There is a very lightly stained outer layer (note the single stained soma) and a very dense band of staining about 100 μm wide. This band is comprised of stained somata (arrow) and processes, and may correspond to layer 2, the fusiform/pyramidal cell layer. Figure 7D shows calbindin (CB) expression in the DCN of another case. There are labeled beaded fibers with a general orientation parallel to the pial surface. The beaded fibers may correspond to the axons of granule cells (Mugnaini et al., 1980) or of cartwheel cells that express CB in the monkey (Rubio et al., 2008).

13. Summary and conclusions

Studies in rodents have implicated the DCN as playing a key role in tinnitus. Especially important is the observation of spontaneous hyperactivity in the DCN which in turn affects activity higher in the auditory system, e.g. in the inferior colliculus (Mulders et al., 2011). This hyperactivity is seen in several species, including rat, chinchilla and hamsters. It begins roughly one week post-trauma, and gradually increases over the next 3–4 weeks (Kaltenbach et al., 1998; Kaltenbach et al., 2000). This time course is long enough that the underlying mechanisms could include a broad range of neuroanatomical and neurochemical changes, potentially including neurogenesis, the outgrowth of new axons and the formation of new synapses and receptors (Manohar et al., 2012; Shore et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011a). For these data to have utility in humans, however, there must be both functional and structural similarities between humans and rodents. Early studies had questioned the similarity of DCN structure across species, suggesting major differences in human and nonhuman primate DCN organization. We therefore undertook a reexamination of DCN organization in several species, including man. Our results indicate that the shape of the projection neurons and the geometric arrangement of the different cell types do vary across species. However, both a laminar organization and a population of granule cells are characteristic of the DCN of all mammalian species. Our analysis suggests two additional points:

The organization of the cat DCN is not “typical” for the animals studied in auditory research, but actually rather unusual. In the cat, but not in rat, mouse or chinchilla, layer 2 is comprised of a row of radially oriented fusiform cells. It is possible that this pattern is typical of Carnivora; we are unaware of any comparative data that support that idea from other carnivore species. A layer 2 with pyramidal cells scattered throughout with no consistent radial orientation, as in rat (Figs. 1 and 4), is actually more the rule than the exception. While the cat was used in early anatomical and physiological studies, its DCN has not been studied in the context of tinnitus. To our knowledge, spontaneous hyperactivity has never been demonstrated in cat DCN under the conditions associated with tinnitus. In one cochlear lesion model, spontaneous activity in the DCN did not change significantly shortly after cochlear destruction, whereas significant decreases were noted in the ventral cochlear nucleus (Koerber et al., 1966).

The data in rat and chinchilla suggest that different rodents can be as different from each other as primates are from cats. This argues in favor of species diversity and against any clear “phylogenetic trend”. Despite the structural differences in the DCN of these species, spontaneous hyperactivity in the DCN of rat, hamster and chinchilla has been linked to behavioral evidence of tinnitus (Bauer et al., 1999; Brozoski et al., 2002; Brozoski and Bauer, 2005; Kaltenbach et al., 2004) suggesting that data from both may be useful in understanding tinnitus in humans.

The implications of this variability of the shape and placement of the projection neurons and granule cells for DCN circuitry are not clear; the connections could be similar even if the geometry is different. From the perspective of the neural basis of tinnitus, the established and widely held view of the human DCN as profoundly different and less well-developed than the cat DCN, is probably not correct. Data are gradually accumulating that the diversity of cell types, if not their precise geometric arrangement, as well as laminar organization of the DCN, are preserved in primates.

In summary, the data support interspecies variability in DCN organization but suggest that two critical features, lamination and a granule cell population, are found in all. These results suggest that the use of animal models in the quest to understand the neural basis of tinnitus is likely to be a profitable pursuit.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Histology

Human

The human cases are from the Witelson Normal Brain Collection (Witelson and McCulloch, 1991). Table 1 shows the age, gender and postmortem interval (PMI) for the cases illustrated in Fig. 7. The brains had been stored in 10% formalin. The brainstems were dissected away from the cerebrum and cerebellum and then cryoprotected in 15% followed by 30% sucrose in 10% formalin. Forty μm thick frozen sections were cut on an AO sliding microtome in a plane transverse to the brainstem. Sections were stored in plastic compartment boxes, 5 sections in each compartment, at 4°C in 5% formalin.

Rats

We used adult (ages 3 months–16 months) male, albino SASCO Sprague-Dawley rats from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). We followed the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23) revised 1996, and all animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University at Buffalo. Animals were housed individually and had ad lib. access to water and standard laboratory rodent chow. They were maintained on a 12 hour light-dark cycle. Rats were deeply anesthetized with 86 mg/kg i.p. of Fatal-plus (Vortech, Pharmaceutical Ltd, Dearborn, MI.) and perfused through the heart with 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The brains were removed, post-fixed for 24 hrs, and then cryoprotected in 15% and then 30% sucrose in PBS. Forty μm thick coronal sections were cut on a cryostat and stored in tissue culture wells in a cryoprotection solution of 30% ethylene glycol and 30% glycerol in 0.1M phosphate buffer at −20°C.

Immunohistochemistry

All processing was on free-floating sections. Sections were removed from the cryoprotectant solution or formalin and rinsed in 0.1 M PBS. All rinses were for 3 × 10 min on a tissue rocker at room temperature (RT). Sections from the human brains were then treated with an antigen retrieval (AR) procedure. Sections were placed individually in glass jars in 20 cc of a sodium citrate-citric acid buffer, pH =2.5 or 8.0. The jars were placed in a water bath preheated to 85° for 20–30 minutes, then removed and cooled at RT for 20 min. The sections were removed from the jars and rinsed again. For all sections, the next step was to block non-specific binding of primary antibodies by incubating in a solution of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1.5 % normal horse serum (NHS, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and 0.1% TritonX-100 (TX) in PBS for 30 min. Sections were then incubated overnight in a solution of PBS,1% BSA, 1.5 % normal serum (Vector) and 0.1% – 2% TritonX-100 (TX) at 4 °C on a tissue rocker. The primary antibodies used were anti-doublecortin (DCX, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, #sc-8066, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-calbindin D-28 (CB, 1:1000, Chemicon/Millipore, #AB 1778, Billerica, MA) and anti- nonphosphorylated neurofilament protein (NPNFP,1:1000, Covance, SMI32P, Princeton Township, NJ). Sections were then rinsed and incubated in the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, following manufacturer’s instructions); further processing was with the Vector ABC method using a Vectastain kit. Immunoreactivity was visualized using the glucose oxidase (GO) modification of the diaminobenzidine (DAB) method (Shu et al., 1988; Van Der Gucht et al., 2006). Sections were mounted onto gelled glass slides, air dried overnight, dehydrated in 70%, 95% and then 100% alcohol, cleared in Histosol (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA), and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

Nissl Sections

The CV-stained sections from the cat (Fig. 3), rat (Fig. 4), chinchilla (Fig. 5) and macaque monkey (Fig. 6) are from archival sections prepared in the course of other projects in this laboratory (Baizer and Baker, 2005; Baizer and Baker, 2006; Baizer et al., 2010; Edelman and Baizer, 2006). CV staining was done according to the protocol of LaBossiere and Glickstein (1976).

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra Witelson for the gift of the human tissue and Debra Kigar for help with the initial dissections. Supported in part by the Department of Physiology and Biophysics (JSB), University at Buffalo and NIH grants to RJS (R01DC00909101 and R01DC009219).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott SD, Hughes LF, Bauer CA, Salvi R, Caspary DM. Detection of glutamate decarboxylase isoforms in rat inferior colliculus following acoustic exposure. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1375–81. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JC. Neuronal morphology in the human cochlear nucleus. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112:1253–61. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1986.03780120017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjamian P, Sereda M, Hall DA. The mechanisms of tinnitus: perspectives from human functional neuroimaging. Hear Res. 2009;253:15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Phillips SC. Is the inferior colliculus an obligatory relay in the cat auditory system? Neurosci Lett. 1984;44:259–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Pettigrew JD, Calford MB, Phillips SC, Wise LZ. Representation of stimulus azimuth by low-frequency neurons in inferior colliculus of the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1985;53:43–59. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baizer JS, Baker JF. Immunoreactivity for calcium-binding proteins defines subregions of the vestibular nuclear complex of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 2005;164:78–91. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2211-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baizer JS, Baker JF. Immunoreactivity for calretinin and calbindin in the vestibular nuclear complex of the monkey. Exp Brain Res. 2006;172:103–13. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baizer JS, Baker JF, Haas K, Lima R. Neurochemical organization of the nucleus paramedianus dorsalis in the human. Brain Res. 2007;1176:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baizer JS, Broussard DM. Expression of calcium-binding proteins and nNOS in the human vestibular and precerebellar brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:872–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.22250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baizer JS, Paolone NA, Kramer V, Sherwood CC, Hof PR. Neurochemical organization of the chimpanzee vestibular brainstem. Soc Neurosci Abs. 2010:583.23/WW16. [Google Scholar]

- Baizer JS, Sherwood CC, Hof PR, Witelson SF, Sultan F. Neurochemical and structural organization of the principal nucleus of the inferior olive in the human. Anat Rec. 2011;294:1198–216. doi: 10.1002/ar.21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft BR, Boettcher FA, Salvi RJ, Wu J. Effects of noise and salicylate on auditory evoked-response thresholds in the chinchilla. Hear Res. 1991;54:20–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90132-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basta D, Ernest A. Noise-induced changes of neuronal spontaneous activity in mice inferior colliculus brain slices. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer CA, Brozoski TJ, Rojas R, Boley J, Wyder M. Behavioral model of chronic tinnitus in rats. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:457–62. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer CA, Turner JG, Caspary DM, Myers KS, Brozoski TJ. Tinnitus and inferior colliculus activity in chinchillas related to three distinct patterns of cochlear trauma. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2564–78. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstad TW, Osen KK, Mugnaini E. Pyramidal neurones of the dorsal cochlear nucleus: a Golgi and computer reconstruction study in cat. Neuroscience. 1984;13:827–54. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawer JR, Morest DK, Kane EC. The neuronal architecture of the cochlear nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1974;155:251–300. doi: 10.1002/cne.901550302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, Bauer CA, Caspary DM. Elevated fusiform cell activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of chinchillas with psychophysical evidence of tinnitus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2383–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02383.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, Bauer CA. The effect of dorsal cochlear nucleus ablation on tinnitus in rats. Hear Res. 2005;206:227–36. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, Ciobanu L, Bauer CA. Central neural activity in rats with tinnitus evaluated with manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) Hear Res. 2007;228:168–79. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkard R, Trautwein P, Salvi R. The effects of click level, click rate, and level of background masking noise on the inferior colliculus potential (ICP) in the normal and carboplatin-treated chinchilla. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;102:3620–7. doi: 10.1121/1.420149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant NB, Benson CG. Parallel auditory pathways: projection patterns of the different neuronal populations in the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei. Brain Res Bull. 2003;60:457–74. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G-D, Tanaka C, Henderson D. Relation between outer hair cell loss and hearing loss in rats exposed to styrene. Hear Res. 2008;243:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GD, Jastreboff PJ. Salicylate-induced abnormal activity in the inferior colliculus of rats. Hear Res. 1995;82:158–78. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00174-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby E, Humphrey T, Lauer E. Correlative anatomy of the nervous system. The Macmillan Company; New York: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA, Miller RL, Young ED. Effects of somatosensory and parallel-fiber stimulation on neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3012–24. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayer AG, Ford AA, Cleaver KM, Yassaee M, Cameron HA. Short-term and long-term survival of new neurons in the rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:563–72. doi: 10.1002/cne.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmel S, Cui YL, Shore SE. Cross-modal interactions of auditory and somatic inputs in the brainstem and midbrain and their imbalance in tinnitus and deafness. Am J Audiol. 2008;17:S193–209. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/07-0045). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmel S, Pradhan S, Koehler S, Bledsoe S, Shore S. Noise overexposure alters long-term somatosensory-auditory processing in the dorsal cochlear nucleus--possible basis for tinnitus-related hyperactivity? J Neurosci. 2012;32:1660–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4608-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding DL, Wang J, Salvi R, Henderson D, Hu BH, McFadden SL, Mueller M. Selective loss of inner hair cells and type-I ganglion neurons in carboplatin-treated chinchillas. Mechanisms of damage and protection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;884:152–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diño MR, Schuerger RJ, Liu Y, Slater NT, Mugnaini E. Unipolar brush cell: a potential feedforward excitatory interneuron of the cerebellum. Neuroscience. 2000;98:625–36. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diño MR, Mugnaini E. Distribution and phenotypes of unipolar brush cells in relation to the granule cell system of the rat cochlear nucleus. Neuroscience. 2008;154:29–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Rodger J, Mulders WH, Robertson D. Tonotopic changes in GABA receptor expression in guinea pig inferior colliculus after partial unilateral hearing loss. Brain Res. 2010;1342:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman A, Baizer JS. Localization of doublecortin kinase-2 in adult rat brain. Neurosci Abs. 2006:225.18. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kashlan HK, Shore SE. Effects of trigeminal ganglion stimulation on the central auditory system. Hear Res. 2004;189:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floris A, Dino M, Jacobowitz DM, Mugnaini E. The unipolar brush cells of the rat cerebellar cortex and cochlear nucleus are calretinin-positive: a study by light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Anat Embryol. 1994;189:495–520. doi: 10.1007/BF00186824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis F, Koulakoff A, Boucher D, Chafey P, Schaar B, Vinet MC, Friocourt G, McDonnell N, Reiner O, Kahn A, McConnell SK, Berwald-Netter Y, Denoulet P, Chelly J. Doublecortin is a developmentally regulated, microtubule-associated protein expressed in migrating and differentiating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:247–56. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JG, Lin PT, Flanagan LA, Walsh CA. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23:257–71. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, Kiang NY, Norris BE. Single unit activity in the posteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1975a;162:247–68. doi: 10.1002/cne.901620206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, Kiang NY, Norris BE. Single unit activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1975b;162:269–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.901620207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, Godfrey MA, Ding D-L, Chen K, Salvi RJ. Amino acid concentrations in chinchilla cochlear nucleus at different times after carboplatin treatment. Hear Res. 2005;206:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Naturally occurring cell death in the developing dentate gyrus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;304:408–18. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackney CM, Osen KK, Kolston J. Anatomy of the cochlear nuclear complex of guinea pig. Anat Embryol. 1990;182:123–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00174013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamernik RP, Patterson JH, Salvi RJ. The effect of impulse intensity and the number of impulses on hearing and cochlear pathology in the chinchilla. J Acoust Soc Am. 1987;81:1118–29. doi: 10.1121/1.394632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman-Patterson TD, Strominger NL. Morphological changes in the cochlear nuclear complex in primate phylogeny and development. J Morphol. 1985;186:289–306. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051860306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D, Hamernik RP, Salvi RJ, Ahroon WA. Comparison of auditory-evoked potentials and behavioral thresholds in the normal and noise-exposed chinchilla. Audiology. 1983;22:172–80. doi: 10.3109/00206098309072780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter P, Ding D, Powers N, Salvi RJ. Quantitative relationship of carboplatin dose to magnitude of inner and outer hair cell loss and the reduction in distortion product otoacoustic emission amplitude in chinchillas. Hear Res. 1997;112:199–215. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd LB, 2nd, Feldman ML. Purkinje-like cells in rat cochlear nucleus. Hear Res. 1994;72:143–58. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain K, Scott RB, Whitworth C, Somani SM, Rybak LP. Dose response of carboplatin-induced hearing loss in rats: antioxidant defense system. Hear Res. 2001;151:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(00)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Weinberger NM, Westenberg IS. Relationships among unit discharge rate, pattern, and phasic arousal in the medical geniculate nucleus of the waking cat. Exp Neurol. 1972;35:337–57. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(72)90159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Weinberger NM. Relationships between rate and pattern of unitary discharges in medial geniculate body of the cat in response to click and amplitude-modulated white-noise stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1973;36:385–97. doi: 10.1152/jn.1973.36.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Adrian HO. Binaural columns in the primary field (A1) of cat auditory cortex. Brain Res. 1977;138:241–57. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Sasaki CT. Salicylate-induced changes in spontaneous activity of single units in the inferior colliculus of the guinea pig. J Acoust Soc Am. 1986;80:1384–91. doi: 10.1121/1.394391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Brennan JF, Sasaki CT. An animal model for tinnitus. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:280–6. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198803000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Sasaki CT. An animal model of tinnitus: a decade of development. Am J Otol. 1994;15:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Godfrey DA, Neumann JB, McCaslin DL, Afman CE, Zhang J. Changes in spontaneous neural activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus following exposure to intense sound: relation to threshold shift. Hear Res. 1998;124:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Afman CE. Hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus after intense sound exposure and its resemblance to tone-evoked activity: a physiological model for tinnitus. Hear Res. 2000;140:165–72. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zhang J, Afman CE. Plasticity of spontaneous neural activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus after intense sound exposure. Hear Res. 2000;147:282–92. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Rachel JD, Mathog TA, Zhang J, Falzarano PR, Lewandowski M. Cisplatin-induced hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and its relation to outer hair cell loss: relevance to tinnitus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:699–714. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zacharek MA, Zhang J, Frederick S. Activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of hamsters previously tested for tinnitus following intense tone exposure. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355:121–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA. Summary of evidence pointing to a role of the dorsal cochlear nucleus in the etiology of tinnitus. Acta oto-laryngol Suppl. 2006a:20–6. doi: 10.1080/03655230600895309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA. The dorsal cochlear nucleus as a participant in the auditory, attentional and emotional components of tinnitus. Hear Res. 2006b:216–217. 224–34. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA. The dorsal cochlear nucleus as a contributor to tinnitus: mechanisms underlying the induction of hyperactivity. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:89–106. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Godfrey DA. Dorsal cochlear nucleus hyperactivity and tinnitus: are they related? Am J Audiol. 2008;17:S148–61. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/08-0004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA. Tinnitus: Models and mechanisms. Hear Res. 2011;276:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, McNelly NA, Hinds JW. Population dynamics of adult-formed granule neurons of the rat olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1985;239:117–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.902390110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazee AM, Han LY, Spongr VP, Walton JP, Salvi RJ, Flood DG. Synaptic loss in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus correlates with sensorineural hearing loss in the C57BL/6 mouse model of presbycusis. Hear Res. 1995;89:109–20. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Gage FH. Experience-induced neurogenesis in the senescent dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3206–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03206.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klis SF, O’Leary SJ, Wijbenga J, de Groot JC, Hamers FP, Smoorenburg GF. Partial recovery of cisplatin-induced hearing loss in the albino guinea pig in relation to cisplatin dose. Hear Res. 2002;164:138–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler SD, Pradhan S, Manis PB, Shore SE. Somatosensory inputs modify auditory spike timing in dorsal cochlear nucleus principal cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:409–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber KC, Pfeiffer RR, Warr WB, Kiang NY. Spontaneous spike discharges from single units in the cochlear nucleus after destruction of the cochlea. Exp neurol. 1966;16:119–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(66)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszeghy A, Pal B, Pap P, Pocsai K, Nagy Z, Szucs G, Rusznak Z. Purkinje-like cells of the rat cochlear nucleus: a combined functional and morphological study. Brain Res. 2009;1297:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus KS, Ding D, Zhou Y, Salvi RJ. Central auditory plasticity after carboplatin-induced unilateral inner ear damage in the chinchilla: up-regulation of GAP-43 in the ventral cochlear nucleus. Hear Res. 2009a;255:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus KS, Ding D, Zhou Y, Salvi RJ. Central auditory plasticity after carboplatin-induced unilateral inner ear damage in the chinchilla: up-regulation of GAP-43 in the ventral cochlear nucleus. Hear Res. 2009b;255:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus KS, Mitra S, Jimenez Z, Hinduja S, Ding D, Jiang H, Gray L, Lobarinas E, Sun W, Salvi RJ. Noise trauma impairs neurogenesis in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2010;167:1216–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBossiere E, Glickstein M. In: Histological processing for the neural sciences. Thomas Charles C., editor. Springfield; Illinois: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Leaver AM, Renier L, Chevillet MA, Morgan S, Kim HJ, Rauschecker JP. Dysregulation of limbic and auditory networks in tinnitus. Neuron. 2011;69:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RA. Somatic (craniocervical) tinnitus and the dorsal cochlear nucleus hypothesis. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20:351–62. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(99)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RA, Abel M, Cheng H. CNS somatosensory-auditory interactions elicit or modulate tinnitus. Exp Brain Res. 2003;153:643–8. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Li X, Wang L, Dong Y, Han H, Liu G. Effects of salicylate on serotoninergic activities in rat inferior colliculus and auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2003;175:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobarinas E, Sun W, Cushing R, Salvi R. A novel behavioral paradigm for assessing tinnitus using schedule-induced polydipsia avoidance conditioning (SIP-AC) Hear Res. 2004;190:109–14. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(04)00019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente de No R. Anatomy of the eighth nerve. III. General plan of structure of the primary cochlear nuclei. Laryngoscope. 1933;43:327–350. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Lobarinas E, Deng A, Goodey R, Stolzberg D, Salvi RJ, Sun W. GABAergic neural activity involved in salicylate-induced auditory cortex gain enhancement. Neuroscience. 2011;189:187–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS. The structure and physiology of the rat auditory system: an overview. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2003;56:147–211. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(03)56005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar S, Paolone NA, Bleichfeld M, Hayes SH, Salvi RJ, Baizer JS. Expression of doublecortin, a neuronal migration protein, in unipolar brush cells of the vestibulocerebellum and dorsal cochlear nucleus of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 2012;202:169–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden SL, Kasper C, Ostrowski J, Ding D, Salvi RJ. Effects of inner hair cell loss on inferior colliculus evoked potential thresholds, amplitudes and forward masking functions in chinchillas. Hear Res. 1998;120:121–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JW, Kiritani T, Pedersen C, Turner JG, Shepherd GMG, Tzounopoulos T. Mice with behavioral evidence of tinnitus exhibit dorsal cochlear nucleus hyperactivity because of decreased GABAergic inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7601–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100223108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milbrandt JC, Holder TM, Wilson MC, Salvi RJ, Caspary DM. GAD levels and muscimol binding in rat inferior colliculus following acoustic trauma. Hear Res. 2000;147:251–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK, Osen KK. The cochlear nuclei in man. Am J Anat. 1979;154:393–418. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001540306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK. The primate cochlear nuclei: loss of lamination as a phylogenetic process. J comp neurol. 1980;193:609–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK, Osen KK, Storm-Mathisen J, Ottersen OP. gamma-Aminobutyric acid and glycine in the baboon cochlear nuclei: an immunocytochemical colocalization study with reference to interspecies differences in inhibitory systems. J Comp Neurol. 1996;369:497–519. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960610)369:4<497::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz N. Comparative aspects of some features of the auditory system of primates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1969;167:357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini E, Warr WB, Osen KK. Distribution and light microscopic features of granule cells in the cochlear nuclei of cat, rat, and mouse. J Comp Neurol. 1980;191:581–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini E, Sekerkova G, Martina M. The unipolar brush cell: a remarkable neuron finally receiving deserved attention. Brain Res Rev. 2011;66:220–45. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlau M, Rauschecker JP, Oestreicher E, Gaser C, Rottinger M, Wohlschlager AM, Simon F, Etgen T, Conrad B, Sander D. Structural brain changes in tinnitus. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:1283–8. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlnickel W, Elbert T, Taub E, Flor H. Reorganization of auditory cortex in tinnitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10340–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders WH, Ding D, Salvi R, Robertson D. Relationship between auditory thresholds, central spontaneous activity, and hair cell loss after acoustic trauma. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:2637–47. doi: 10.1002/cne.22644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas-Puel C, Faulconbridge RL, Guitton M, Puel JL, Mondain M, Uziel A. Characteristics of tinnitus and etiology of associated hearing loss: a study of 123 patients. The international tinnitus journal. 2002;8:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Young ED. What’s a cerebellar circuit doing in the auditory system? Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann M, Muller N, Schlee W, Weisz N. Rapid increases of gamma power in the auditory cortex following noise trauma in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:568–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen KK. Cytoarchitecture of the cochlear nuclei in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1969;136:453–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.901360407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petreanu L, Alvarez-Buylla A. Maturation and death of adult-born olfactory bulb granule neurons: role of olfaction. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6106–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06106.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinchoff RJ, Burkard RF, Salvi RJ, Coad ML, Lockwood AH. Modulation of tinnitus by voluntary jaw movements. Am J Otol. 1998;19:785–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachel JD, Kaltenbach JA, Janisse J. Increases in spontaneous neural activity in the hamster dorsal cochlear nucleus following cisplatin treatment: a possible basis for cisplatin-induced tinnitus. Hear Res. 2002;164:206–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschecker JP, Leaver AM, Muhlau M. Tuning out the noise: limbic-auditory interactions in tinnitus. Neuron. 2010;66:819–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LE, Eggermont JJ, Caspary DM, Shore SE, Melcher JR, Kaltenbach JA. Ringing ears: the neuroscience of tinnitus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14972–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4028-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio ME, Gudsnuk KA, Smith Y, Ryugo DK. Revealing the molecular layer of the primate dorsal cochlear nucleus. Neuroscience. 2008;154:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi RJ, Hamernik RP, Henderson D. Discharge patterns in the cochlear nucleus of the chinchilla following noise induced asymptotic threshold shift. Exp Brain Res. 1978;32:301–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00238704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi RJ, Ahroon WA, Perry JW, Gunnarson AD, Henderson D. Comparison of psychophysical and evoked-potential tuning curves in the chinchilla. Am J Otolaryngol. 1982a;3:408–16. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(82)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi RJ, Giraudi DM, Henderson D, Hamernik RP. Detection of sinusoidally amplitude modulated noise by the chinchilla. J Acoust Soc Am. 1982b;71:424–9. doi: 10.1121/1.387445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi RJ, Saunders SS, Gratton MA, Arehole S, Powers N. Enhanced evoked response amplitudes in the inferior colliculus of the chinchilla following acoustic trauma. Hear Res. 1990;50:245–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90049-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders SS, Shivapuja BG, Salvi RJ. Auditory intensity discrimination in the chinchilla. J Acoust Soc Am. 1987;82:1604–7. doi: 10.1121/1.395150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaette R, McAlpine D. Tinnitus with a normal audiogram: physiological evidence for hidden hearing loss and computational model. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13452–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2156-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore S, Zhou J, Koehler S. Neural mechanisms underlying somatic tinnitus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:107–23. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SE, Vass Z, Wys NL, Altschuler RA. Trigeminal ganglion innervates the auditory brainstem. J Comp Neurol. 2000;419:271–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000410)419:3<271::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SE, Koehler S, Oldakowski M, Hughes LF, Syed S. Dorsal cochlear nucleus responses to somatosensory stimulation are enhanced after noise-induced hearing loss. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:155–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu SY, Ju G, Fan LZ. The glucose oxidase-DAB-nickel method in peroxidase histochemistry of the nervous system. Neurosci Lett. 1988;85:169–71. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons R, Dambra C, Lobarinas E, Stocking C, Salvi R. Head, neck and eye movements that modulate tinnitus. Sem Hear. 2008;29:361–370. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1095895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz WB. Differences between guinea pig and rat in the dorsal cochlear nucleus: expression of calcium-binding proteins by cartwheel and Purkinje-like cells. Hear Res. 1997;107:136–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz WB. Unipolar brush cells in the human cochlear nuclei identified by their expression of a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR2/3) Neurosci Lett. 2001;316:161–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz WB. Purkinje-like cells in the cochlear nucleus of the Common Tree Shrew (Tupaia glis) identified by calbindin immunohistochemistry. Brain Res. 2003;983:230–2. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengs CH, Klis SF, Huizing EH, Smoorenburg GF. Cisplatin ototoxicity. An electrophysiological dose-effect study in albino guinea pigs. Hear Res. 1998;124:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzberg D, Chen GD, Allman BL, Salvi RJ. Salicylate-induced peripheral auditory changes and tonotopic reorganization of auditory cortex. Neuroscience. 2011;180:157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Lu J, Stolzberg D, Gray L, Deng A, Lobarinas E, Salvi RJ. Salicylate increases the gain of the central auditory system. Neuroscience. 2009;159:325–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JG, Brozoski TJ, Bauer CA, Parrish JL, Myers K, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Gap detection deficits in rats with tinnitus: a potential novel screening tool. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:188–95. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzounopoulos T. Mechanisms of synaptic plasticity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus: plasticity-induced changes that could underlie tinnitus. Am J Audiol. 2008;17:S170–5. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2008/07-0030). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Gucht E, Youakim M, Arckens L, Hof PR, Baizer JS. Variations in the structure of the prelunate gyrus in Old World monkeys. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:753–75. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vass Z, Shore SE, Nuttall AL, Miller JM. Direct evidence of trigeminal innervation of the cochlear blood vessels. Neuroscience. 1998;84:559–67. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagoner JL, Kulesza RJ., Jr Topographical and cellular distribution of perineuronal nets in the human cochlear nucleus. Hear Res. 2009;254:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Brozoski TJ, Turner JG, Ling L, Parrish JL, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Plasticity at glycinergic synapses in dorsal cochlear nucleus of rats with behavioral evidence of tinnitus. Neuroscience. 2009;164:747–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Brozoski TJ, Caspary DM. Inhibitory neurotransmission in animal models of tinnitus: maladaptive plasticity. Hear Res. 2011a;279:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Brozoski TJ, Caspary DM. Inhibitory neurotransmission in animal models of tinnitus: maladaptive plasticity. Hear Res. 2011b;279:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HT, Luo B, Huang YN, Zhou KQ, Chen L. Sodium salicylate suppresses serotonin-induced enhancement of GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents in rat inferior colliculus in vitro. Hear Res. 2008;236:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Salvi RJ, Powers N. Plasticity of response properties of inferior colliculus neurons following acute cochlear damage. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:171–83. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ding D, Salvi RJ. Functional reorganization in chinchilla inferior colliculus associated with chronic and acute cochlear damage. Hear Res. 2002a;168:238–49. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ding D, Salvi RJ. Functional reorganization in chinchilla inferior colliculus associated with chronic and acute cochlear damage. Hear Res. 2002b;168:238–49. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster D. An overview of mammalin auditory pathways with an emphasis on humans. In: Webster D, Popper A, Fay R, editors. The Mammalin Auditory Pathway: Neuroanatomy. Springer-Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Webster DB, Trune DR. Cochlear nuclear complex of mice. Am J Anat. 1982;163:103–30. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001630202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Ding D, Sun W, Xu-Friedman MA, Salvi R. Effects of sodium salicylate on spontaneous and evoked spike rate in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hear Res. 2010;267:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.03.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard F, Ryugo DK. Anatomy of the central auditory system. In: Willott J, Thomas Charles C, editors. The auditory psychobiology of the mouse. Springfield; ILL: 1983. pp. 201–304. [Google Scholar]

- Winner B, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Aigner R, Winkler J, Kuhn HG. Long-term survival and cell death of newly generated neurons in the adult rat olfactory bulb. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1681–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witelson SF, McCulloch PB. Premortem and postmortem measurement to study structure with function: a human brain collection. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:583–91. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Lobarinas E, Zhang L, Turner J, Stolzberg D, Salvi R, Sun W. Salicylate induced tinnitus: behavioral measures and neural activity in auditory cortex of awake rats. Hear Res. 2007;226:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharek MA, Kaltenbach JA, Mathog TA, Zhang J. Effects of cochlear ablation on noise induced hyperactivity in the hamster dorsal cochlear nucleus: implications for the origin of noise induced tinnitus. Hear Res. 2002;172:137–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Nannapaneni N, Zhou J, Hughes LF, Shore S. Cochlear damage changes the distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters associated with auditory and nonauditory inputs to the cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4210–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0208-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS, Kaltenbach JA, Godfrey DA, Wang J. Origin of hyperactivity in the hamster dorsal cochlear nucleus following intense sound exposure. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:819–31. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132:645–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Shore S. Projections from the trigeminal nuclear complex to the cochlear nuclei: a retrograde and anterograde tracing study in the guinea pig. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:901–7. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Nannapaneni N, Shore S. Vessicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 are differentially associated with auditory nerve and spinal trigeminal inputs to the cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:777–87. doi: 10.1002/cne.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Ding D, Kraus KS, Yu D, Salvi RJ. Functional and structural changes in the chinchilla cochlea and vestibular system following round window application of carboplatin. Audiol Med. 2009;7:189–199. doi: 10.3109/16513860903335795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]