Abstract

Systemic inflammation as evidenced by the Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) predicts cancer-specific survival in various types of cancer. The aim of this study was to evaluate the significance of GPS in patients with both synchronous and metachronous unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRLM). The subjects were 40 patients who were diagnosed as having unresectable CRLM between March 2000 and August 2010 at Jikei University Hospital. For the assessment of systemic inflammatory response using the GPS, the patients were classified into three groups: patients with normal albumin (≥3.5 g/dl) and normal CRP (≤1.0 mg/dl) as GPS 0 (n=27), those with low albumin (<3.5 g/dl) or elevated CRP (>1.0 mg/dl) as GPS 1 (n=6), and both low albumin (<3.5 g/dl) and elevated CRP (>1.0 mg/dl) as GPS 2 (n=7). We retrospectively investigated the relationship between patient characteristics including GPS and survival using univariate and multivariate analyses. Results of the univariate analysis revealed that absence of primary tumor resection (p=0.0161), absence of systemic chemotherapy (p=0.0119), serum carcinoembroynic antigen (CEA) of ≥100 ng/ml (p=0.0148), serum carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 of ≥100 U/ml (p<0.0001) and GPS 2 (p=0.0362) were significant predictors of poor survival. Results of the multivariate analysis revealed that serum CEA of ≥100 ng/ml (p=0.0015), CA19-9 of ≥100 U/ml (p<0.0001) and GPS 2 (p=0.0042) were independent predictors. In conclusion, GPS at diagnosis of unresectable CRLM is an independent prognostic predictor of overall survival.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, liver metastasis, Glasgow prognostic score, prognosis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common type of cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide (1). Liver metastasis is one of the most important prognostic factors for patients with colorectal cancer, and approximately 25% of patients present with liver metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis of colorectal cancer. A further 40–50% of patients develop colorectal liver metastases (CRLM) within three years of resection of the primary tumor (2). Hepatic resection is the most effective and potentially curative therapy for CRLM (3–6). The five-year overall survival rate following hepatic resection is reported to range from 28 to 50% (7–11). However, liver resection can be performed only in approximately 10–20% of patients with CRLM due to unresectable multiple and bilobar metastases (12). The survival rates of patients who do not undergo resection are poor and do not exceed 2% at five years (13,14). Therefore, assessment of prognostic predictors is important for the management of unresectable CRLM patients.

Previous studies have indicated that the measurement of the systemic inflammatory response by a combination of serum CRP and albumin concentration, i.e., the Glasgow prognostic score (GPS), have been shown to predict cancer-specific survival (15,16). However, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between the GPS and prognosis in patients with both synchronous and metachronous unresectable CRLM has yet to be reported.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the significance of GPS in patients with both synchronous and metachronous unresectable CRLM.

Patients and methods

Patients

Between March 2000 and August 2010, 55 patients were diagnosed as having unresectable liver metastasis due to colorectal cancer in the Department of Surgery, Jikei University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. Of these, 15 patients were excluded, 6 for concomitant microwave coagulation or radiofrequency ablation therapy, 4 due to lack of data, and 5 who were lost to follow-up, leaving the remaining 40 patients for this study.

Treatments administered

Prior to 2003, we defined ≥5 bilobar metastases of the liver as being unresectable; currently the definition of H3 liver metastasis by the Japanese classification of colorectal carcinoma (17). Since 2004, we redefined unresectable CRLM as follows: Cases with insufficient hepatic reserve or remnant liver volume after complete resection of CRLM. During both periods mentioned, patients exhibiting poor performance status and metastasis to other organs, with the exception of the lungs, as well as local recurrence or para-aortic lymph node metastasis were generally judged as unresectable. For unresectable liver metastasis, systemic chemotherapy was administered based on performance status. Prior to 2003, leucovorin (LV)/5-fluorouracil (5FU) or irinotecan (CPT-11) chemotherapy were the preferred method of treatment. Since 2003, this was replaced with LV and 5FU combined with CPT-11 (FOLFIRI) or oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) as the preferred method of treatment. A resection of the primary tumor in the rectum or colon was performed for patients with good performance status and for those with intestinal obstruction.

Chemical profiles were routinely measured upon diagnosis of CRLM prior to systemic chemotherapy. The serum biochemistry data included serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP) and tumor marker levels including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9. Serum CEA and CA19-9 were classified as: <100 or ≥100 ng/ml and <100 or ≥100 U/ml, respectively.

For the assessment of systemic inflammatory response using GPS, patients were classified into three groups: Patients with normal albumin (≥3.5 g/dl) and normal CRP (≤1.0 mg/dl) as GPS 0 (n=27), those with low albumin (<3.5 g/dl) or elevated CRP (>1.0 mg/dl) as GPS 1 (n=6), and both low albumin (<3.5 g/dl) and elevated CRP (>1.0 mg/dl) as GPS 2 (n=7).

The relationship between patient characteristics and overall survival was investigated following the diagnosis of unresectable CRLM by univariate and multivariate analyses. The factors investigated included age, gender, synchronous or metachronous CRLM, site of primary tumor (colon or rectum), presence or absence of primary tumor resection, primary tumor stage (II, III or IV) according to the International Union Against Cancer TMN classification (18), presence or absence of extrahepatic metastases, presence or absence of systemic chemotherapy for CRLM, serum CEA, serum CA 19-9 and GPS (0, 1 or 2).

GPS 0, 1 and 2 were compared using the following factors: Age, gender, synchronous or metachronous CRLM, site of primary tumor, presence or absence of primary tumor resection, primary tumor stage, presence or absence of extrahepatic metastases, presence or absence of systemic chemotherapy for CRLM, serum AST, ALT, CEA <100 or ≥100 ng/ml and CA19-9 <100 and ≥100 U/ml.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Univariate analysis was performed using the non-paired t-test and Chi-square test. Analysis of overall survival was performed using the log-rank test. P-values were considered statistically significant when the associated probability was <0.05.

Results

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival after the diagnosis of unresectable CRLM and patient characteristics

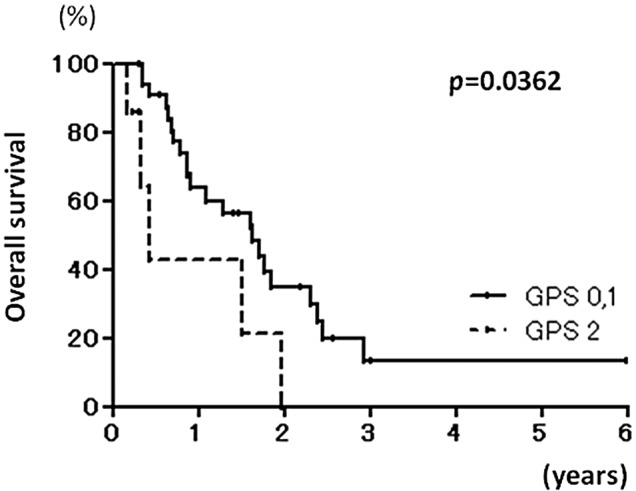

The relationship between the patient characteristics and overall survival after the diagnosis of unresectable CRLM was investigated (Table I). In the univariate analysis, overall survival was worse in the absence of primary tumor resection (p=0.0161), absence of systemic chemotherapy (p=0.0119) and GPS 2 (p=0.0362, Fig. 1).

Table I.

Univariate analysis of overall survival after the diagnosis of unresectable CRLM.

| Overall survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Factor | N | Median (years) | P-value |

| Age (years) | |||

| <60 | 10 | 1.18 | 0.8451 |

| ≥60 | 30 | 0.66 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 30 | 1.18 | 0.7956 |

| Female | 10 | 0.74 | |

| Timing of tumor | |||

| Synchronous | 26 | 0.74 | 0.0853 |

| Metachronous | 14 | 1.65 | |

| Primary site | |||

| Colon | 23 | 1.46 | 0.5902 |

| Rectum | 17 | 0.90 | |

| Primary tumor resection | |||

| Yes | 32 | 1.43 | 0.0161 |

| No | 8 | 0.48 | |

| Primary tumor stage | |||

| II,III | 11 | 1.59 | 0.1227 |

| IV | 29 | 0.78 | |

| Extrahepatic disease | |||

| Yes | 24 | 1.10 | 0.4308 |

| No | 16 | 0.88 | |

| Chemotherapy for CRLM | |||

| Yes | 34 | 1.18 | 0.0119 |

| No | 6 | 0.51 | |

| Serum CEA (ng/ml) | |||

| <100 | 22 | 1.55 | 0.0148 |

| ≥100 | 18 | 0.62 | |

| Serum CA19-9 (U/ml) | |||

| <100 | 30 | 1.55 | <0.0001 |

| ≥100 | 10 | 0.62 | |

| GPS | |||

| 0,1 | 33 | 1.28 | 0.0362 |

| 2 | 7 | 0.33 | |

CRLM, colorectal cancer liver metastases; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival in Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) 0 or 1 and GPS 2 patients.

In the multivariate analysis, significant factors in the univariate analysis including presence or absence of primary tumor resection, presence or absence of systemic chemotherapy, serum CEA <100 or ≥100 ng/ml, serum CA19-9 <100 or ≥ 100 U/ml and GPS 0, 1 or 2 were used, and serum CEA ≥100 ng/ml (p=0.0015), CA19-9 ≥100 U/ml (p<0.0002) and GPS 2 (0.0042) were found to be independent and significant predictors of overall survival (Table II).

Table II.

Multivariate analysis of overall survival following diagnosis of unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRLM).

| Factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Primary tumor resection (No) | 1.299 (0.323–5.216) | 0.7126 |

| Chemotherapy for CRLM (No) | 1.991 (0.493–8.034) | 0.3334 |

| Serum CEA (≥100 ng/ml) | 5.314 (1.891–14.935) | 0.0015 |

| Serum CA19-9 (≥100 U/ml) | 22.331 (5.310–93.911) | <0.0001 |

| GPS 2 | 7.603 (1.899–30.488) | 0.0042 |

CI, confidence interval.

Association between patient characteristics and GPS

The relationship between patient characteristics and GPS were investigated (Table III). The univariate analysis demonstrated that GPS 2 patients had a significantly higher absence of systemic chemotherapy than those in GPS 0 or 1 (p=0.0006), whereas the other factors in the GPS 0 or 1 and 2 groups were comparable.

Table III.

Univariate analysis of patients characteristics with regards to the Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) at the diagnosis of unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases (CRLM).

| GPS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Factor | 0,1 (n=33) | 2 (n=7) | P-value |

| Age (years) | 66.4±10.1 | 64.9±7.6 | 0.7325 |

| Gender (male:female) | 25:8 | 5:2 | 0.8101 |

| Timing of tumor (synchronous:metachronous) | 21:12 | 5:2 | 0.6946 |

| Primary site (colon:rectum) | 20:13 | 3:4 | 0.3882 |

| Primary tumor resection (yes:no) | 28:5 | 4:3 | 0.0960 |

| Primary tumor stage (II,III:IV) | 10:23 | 1:6 | 0.3887 |

| Extrahepatic disease (yes:no) | 19:14 | 5:2 | 0.4968 |

| Chemotherapy for CRLM (yes:no) | 31:2 | 3:4 | 0.0006 |

| Serum AST (IU/l) | 29.1±20.8 | 33.3±24.1 | 0.6368 |

| Serum ALT (IU/l) | 24.2±25.0 | 16.6±12.9 | 0.4423 |

| Serum CEA (<100:≥100 ng/ml) | 19:14 | 3:4 | 0.5050 |

| Serum CA19-9 (<100:≥100 U/ml) | 25:8 | 5:2 | 0.8101 |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA-19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Discussion

Since 20–30% of patients with colorectal cancer have synchronous or metachronous liver metastases, their management is a common and important clinical problem. Several reports have discussed the predictors of long-term survival for patients with CRLM. Jaeck et al reported that three factors, serosa infiltration, involvement of peritumoral lymph nodes around the primary colorectal tumor and a liver resection margin of <1 cm, proved to be independently significant by multivariate analysis (19). Minagawa et al reported that the stage of the primary tumor (III or IV), lymph node metastasis and multiple nodules were significantly associated with a poor prognosis in multivariate analysis (10). In the current study, results of the multivariate analysis revealed that serum CEA ≥100 ng/ml, serum CA19-9 ≥100 U/ml and GPS 2 were independent significant predictors for patients with unresectable CRLM.

The GPS was first reported as a predictor of prognosis of inoperable non-small cell lung cancer in 2003 (20). The GPS was shown to predict prognosis in patients with various inoperable tumors of the lung (21), breast (22), esophagus or stomach (23), pancreas (24), kidney (25) and colorectum (26). Specifically, with regards to inoperable colorectal cancer, Leitch et al reported that GPS was associated with a poor outcome in 84 patients with synchronous CRLM (26). However, no evidence currently exists showing the prognostic value of the GPS in patients with both synchronous and metachronous unresectable CRLM. In the current study, results of the multivariate analysis demonstrated that the GPS was a significant and independent predictor of poor overall survival for patients with both synchronous and metachronous unresectable CRLM. Therefore, the GPS may be a useful predictor of prognosis for patients with unresectable CRLM, including synchronous and metachronous CRLM. The reasons for the association between the GPS and prognosis remain unclear, but with respect to metastatic unresectable disease it is worth considering that chronic activation of the systemic inflammatory response is associated with an increase in weight loss and fatigue resulting in decreased performance status and survival.

Recent chemotherapy including LV and 5FU combined with CPT-11 or oxaliplatin has survival benefits for patients with advanced colorectal cancer, including unresectable liver metastasis (27–30). Therefore, measurement of the GPS prior to chemotherapy for CRLM might be a prognostic indicator, and may contribute to decisions regarding choice of therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, following diagnosis of unresectable CLRM GPS was found to be an independent and significant predictor for overall survival. Measurement of the GPS may help decision-making in the management of patients with CLRM.

References

- 1.Weitz J, Koch M, Debus J, Höhler T, Galle PR, Büchler MW. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:153–165. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17706-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Reilly DA, Poston GJ. Colorectal liver metastases: current and future perspectives. Future Oncol. 2006;2:525–531. doi: 10.2217/14796694.2.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodgers MS, McCall JL. Surgery for colorectal liver metastases with hepatic lymph node involvement: a systematic review. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1142–1155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin LW, Warren RS. Current management of colorectal liver metastases. Surg Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;9:853–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penna C, Nordlinger B. Colorectal metastasis (liver and lung) Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1075–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(02)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato T, Yasui K, Hirai T, Kanemitsu Y, Mori T, Sugihara K, Mochizuki H, Yamamoto J. Therapeutic results for hepatic metastasis of colorectal cancer with special reference to effectiveness of hepatectomy: analysis of prognostic factors for 763 cases recorded at 18 institutions. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:S22–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.DCR.0000089106.71914.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, Balladur P, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, Jaeck D. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver: a prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Cancer. 1996;77:1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seifert JK, Böttger TC, Weigel TF, Gönner U, Junginger T. Prognostic factors following liver resection for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minagawa M, Makuuchi M, Torzilli G, Takayama T, Kawasaki S, Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, Imamura H. Extension of the frontiers of surgical indications in the treatment of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2000;231:487–499. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200004000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonas S, Thelen A, Benckert C, Spinelli A, Sammain S, Neumann U, Rudolph B, Neuhaus P. Extended resections of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31:511–521. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaeck D, Oussoultzoglou E, Rosso E, Greget M, Weber JC, Bachellier P. A two-stage hepatectomy procedure combined with portal vein embolization to achieve curative resection for initially unresectable multiple and bilobar colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;240:1037–1049. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000145965.86383.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood CB, Gillis CR, Blumgart LH. A retrospective study of the natural history of patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Clin Oncol. 1976;2:285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner JS, Adson MA, Van Heerden JA, Adson MH, Ilstrup DM. The natural history of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a comparison with resective treatment. Ann Surg. 1984;199:502–508. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198405000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMillan DC. An inflammation-based prognostic score and its role in the nutrition-based management of patients with cancer. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:257–262. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108007131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMillan DC, Crozier JE, Canna K, Angerson WJ, McArdle CS. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) in patients undergoing resection for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:881–886. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese classification of colorectal carcinoma. 1st English ed. Kanehara Co., Ltd.; Tokyo: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobin LH, Wittekind, editors. UICC TNM classification of malignant tumors. 5th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaeck D, Bachellier P, Guiguet M, Boudjema K, Vaillant JC, Balladur P, Nordlinger B. Long-term survival following resection of colorectal hepatic metastases. Association Française de Chirurgie. Br J Surg. 1997;84:977–980. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800840719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Evaluation of cumulative prognostic scores based on the systemic inflammatory response in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1028–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Comparison of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) with performance status (ECOG) in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy for inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1704–1706. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Murri AM, Bartlett JM, Canney PA, Doughty JC, Wilson C, McMillan DC. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crumley AB, McMillan DC, McKernan M, McDonald AC, Stuart RC. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with inoperable gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:637–641. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glen P, Jamieson NB, McMillan DC, Carter R, Imrie CW, McKay CJ. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2006;6:450–453. doi: 10.1159/000094562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsey S, Lamb GW, Aitchison M, Graham J, McMillan DC. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with metastatic renal cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:205–212. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leitch EF, Chakrabarti M, Crozier JE, McKee RF, Anderson JH, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of selected markers of the systemic inflammatory response in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1266–1270. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C, Rosen LS, Fehrenbacher L, Moore MJ, Maroun JA, Ackland SP, Locker PK, Pirotta N, Elfring GL, Miller LL. Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. Irinotecan Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:905–914. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Douillard JY, Cunningham D, Roth AD, Navarro M, James RD, Karasek P, Jandik P, Iveson T, Carmichael J, Alakl M, et al. Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Gramont A, Vignoud J, Tournigand C, Louvet C, André T, Varette C, Raymond E, Moreau S, Le Bail N, Krulik M. Oxaliplatin with high-dose leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil 48-hour continuous infusion in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:214–219. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poston GJ. The use of irinotecan and oxaliplatin in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]