Introduction

In my last article, I explained that animal welfare concerns not only physical health, but also the state of the animal's mind and the extent to which the animal's nature is satisfied (1). This article examines the challenges of animal welfare assessment; assessment of animal abuse (2,3) is not included.

Approaches to welfare assessment

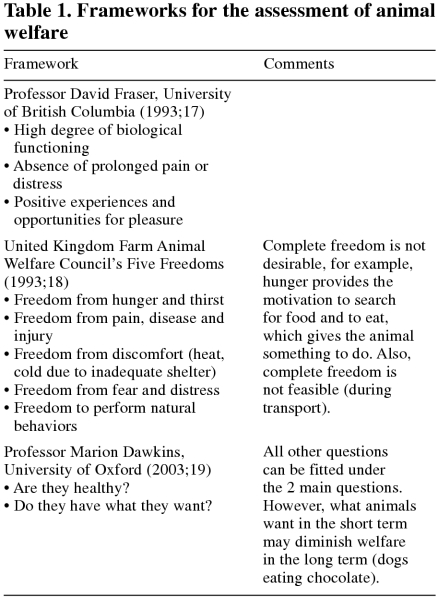

There is no established method for assessing animal welfare, but various frameworks have been suggested (Table 1). Their application requires knowledge of animal health and production, and species-typical behavior. Knowledge of the latter may come from studies of the species' lifestyle in the wild (4).

Table 1.

Research is being done to develop practical methods of assessing welfare. One approach used the opinions of 35 experts, including veterinarians, to devise a list of questions for assessment of the welfare of poultry, cattle, and pigs during a half-day herd or flock visit (5). In another approach, the welfare of pregnant sows in 15 different housing systems was predicted, by using the available scientific data in a computer model (6,7). There is a large but incomplete body of data on the welfare of farm and laboratory animals, but fewer data are available on companion animals. However, the welfare or “quality of life” of companion animals is now being examined by veterinarians (8,9,10), and research is being done on this topic in Canada (10) and Denmark (Stine Christiansen, personal communication, 2003).

Importance of animal-centered outcomes

Any welfare assessment should include animal- centered outcomes, yet the methods used to assess farm animal welfare have tended to focus on measures of the environment (11). Such measures are relatively easy to obtain, whereas many animal- centered outcomes are qualitative and difficult to assess, particularly in herds. Failure to include animal-centered outcomes can lead to erroneous assessments. For example, with the United Kingdom's (UK) Freedom Foods scheme, in which products from livestock kept in conditions that enhance welfare are sold at a premium in supermarkets, participating farms are audited, but the auditing system has been questioned; while the farms have to meet stringent environmental requirements with respect to welfare, some of the animals are faring no better, and sometimes worse, than those on nonparticipating farms, particularly in regard to health (5). This situation appears to have arisen because the audits have not included many animal-centered outcomes (5,11) and perhaps because the “welfare-friendly” environmental changes have not been accompanied by sufficient changes in stockmanship. For example, the daily monitoring of birds' health might require more labor in an extensive system for laying hens than in caged systems. Work is now underway to address welfare concerns in the Freedom Foods scheme by improving both the auditing scheme and farmers' judgement of welfare (degrees of lameness in cows [11]).

Is anthropomorphism wrong?

Welfare assessment is potentially subjective, as is the choice of a cutoff point for deciding whether welfare is acceptable or unacceptable (12). Some subjectivity may be desirable; for example, anthropomorphism can be “a good starting point for predicting animal emotions” (13). One research approach argues that subjective assessments are unacceptable only in our dualistic Cartesian framework which holds that feelings or experience, being internal, cannot be measured objectively (14). Research using a non-Cartesian, subjective approach is supported by the UK and Scottish Agriculture Departments with the goal of developing a practical method of on-farm welfare assessment (14,15). Drawing on arguments from the philosophy of language, the researchers are examining whether human beings' descriptions of pigs' behavior (relaxed, cautious) might provide valid, reliable descriptors of aspects of the animals' welfare. Preliminary results have supported the hypothesis (15; Francoise Wemelsfelder, personal communication, 2001) and the research continues.

Veterinarians and welfare assessment

Expertise in animal welfare assessment is scarce. Animal welfare scientists are experts in mental and natural aspects of welfare, but usually they do not carry out extension work. Veterinarians are expert in physical welfare, but they may not be adequately equipped to give a holistic summary of how an animal or a group of animals are faring. Judgements of welfare are influenced by values (12). However, judgements should become easier when more is known about the factors affecting the welfare of a given species within a particular management system, and how to integrate these factors.

Veterinarians are highly skilled at integrating information, and this is valuable in welfare assessment. Animal welfare, like disease severity, exists along a continuum and is qualitative. Disease severity ranges from nonexistent (the animal does not have the disease) to extreme (the animal is moribund). Welfare ranges from optimal (the animal's body and mind are in an optimal state and his/her nature is satisfied) to minimal (none of the 3 aspects of welfare is good). The difference between assessing welfare and assessing disease severity is that, in the latter case, assessment is based on a relatively small number of physical measures with (usually) well-established normal ranges. In contrast, an assessment of animal welfare must be based on a wide range of measures in addition to health indices. Many of these measures are complex. Normal ranges may be difficult to establish and/or interpret because of individuality due to breed, temperament, and other factors. This calls for items to be weighted appropriately. For species kept as individuals, it is difficult to generate a valid, generalizable method of weighting. For example, one dog may not enjoy walks or be very interested in food, and his/her real pleasure may be in playing certain games; the reverse may be true of another dog.

So, can we assess welfare?

As veterinarians become more aware of the developments in animal welfare science, they will be especially well placed to weigh the factors affecting welfare in a given case and make a judgement. Until adequate protocols for welfare assessment are available, veterinarians should ensure that nonphysical aspects of welfare are included, using one of the frameworks in Table 1. In addition, the profession should always be ready to learn from animal welfare scientists and to work with them.

Having defined animal welfare (16) and examined how we might assess it, in the next article I will explore more closely the question raised in the first article of this series (17): how might veterinarians do more for animal welfare?

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Kip Lemke for help with the in-practice tip.

References

- 1.Hewson CJ. What is animal welfare? Common definitions and their practical consequences. Can Vet J 2003;44:496–499. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Patronek GJ. Tuft's animal care and condition scales for assessing body condition, weather and environmental safety, and physical care in dogs. In: Manual to Aid Veterinarians in Preventing, Recognizing, and Verifying Animal Abuse. American Humane Association 1997.

- 3.Crook A. The CVMA animal abuse position — How we got here. Can Vet J 2000; 41:634–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Clubb R, Mason G. Lifestyle in the wild predicts captive welfare in the carnivora. Proc UFAW Symposium Science in the Service of Animal Welfare 2003:5.

- 5.Whay HR, Main DCJ, Green LE, Webster AJF. Animal-based measures for the assessment of welfare state of dairy cattle, pigs, laying hens: consensus of expert opinion. Anim Welfare 2003;12:205–217.

- 6.Bracke MBM, Sprujit BM, Metz JHM, Schouten WGP. Decision support system for overall welfare assessment in pregnant sows A: Model structure and weighting procedure. J Anim Sci 2002;80:1819–1834. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bracke MBM, Metz JHM, Sprujit BM, Schouten WGP. Decision support system for overall welfare assessment in pregnant sows B: Validation by expert opinion. J Anim Sci 2002;80:1835–1845. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.McMillan FD. Quality of life in animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000;216:1904–1910. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.McMillan FD. Maximising quality of life in ill animals. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2003;39:227–235. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hewson CJ, Wojciechowska JI, Patronek GJ, Guy NC, Timmins V, Bate LA. But is she suffering? Novel instrument to assess quality of life of pet dogs. Anim Welfare 2003 (in press).

- 11.Main DCJ, Whay HR, Green LE, Webster AJF. Farm assurance and on-farm welfare. Cattle Practice 2002;10:181–182.

- 12.Fraser D, Weary DM, Pajor EA, Milligan BN. A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Anim Welfare 1997;6:187–205.

- 13.Morton D. Assessing the impact of fear, anxiety and boredom in animals. Vet Rec 2003;152:639–640.

- 14.Wemelsfelder F. The scientific validity of subjective concepts in models of animal welfare. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1997;53:75–88.

- 15.Wemelsfelder F, Hunter EA, Mendl M, Lawrence AB. The spontaneous qualitative assessment of behavioural expression in pigs: first explorations of a novel methodology for integrative animal welfare measurement. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2000;67:193–215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hewson CJ. Focus on animal welfare. Can Vet J 2003;44:335–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Fraser D. Assessing animal well-being: Common sense, uncommon science. In: Food Animal Well-Being. West Lafayette. Purdue Univ Office Agric Res Prog 1993: 37–54.

- 18.Farm Animal Welfare Council. Report on Priorities for Animal Welfare Research and Development. Surbiton, Surrey: Farm Animal Welfare Council 1993.

- 19.Dawkins MS. Using behaviour to assess animal welfare. Proc UFAW Symposium Science in the Service of Animal Welfare. 2003:2.

- 20.2002 Annual Report of the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. Can Vet J 2003;44:541–550.