Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Airway remodelling is a consequence of long-term inflammation and MAPKs are key signalling molecules that drive pro-inflammatory pathways. The endogenous MAPK deactivator – MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) – is a critical negative regulator of the myriad pro-inflammatory pathways activated by MAPKs in the airway.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Herein we investigated the molecular mechanisms responsible for the upregulation of MKP-1 in airway smooth muscle (ASM) by the corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, added alone and in combination.

KEY RESULTS

MKP-1 is a corticosteroid-inducible gene whose expression is enhanced by long-acting β2-agonists in an additive manner. Formoterol induced MKP-1 expression via the β2-adrenoceptor and we provide the first direct evidence (utilizing overexpression of PKIα, a highly selective PKA inhibitor) to show that PKA mediates β2-agonist-induced MKP-1 upregulation. Dexamethasone activated MKP-1 transcription in ASM cells via a cis-acting corticosteroid-responsive region located between −1380 and −1266 bp of the MKP-1 promoter. While the 3′-untranslated region of MKP-1 contains adenylate + uridylate elements responsible for regulation at the post-transcriptional level, actinomycin D chase experiments revealed that there was no increase in MKP-1 mRNA stability in the presence of dexamethasone, formoterol, alone or in combination. Rather, there was an additive effect of the asthma therapeutics on MKP-1 transcription.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Taken together, these studies allow us a greater understanding of the molecular basis of MKP-1 regulation by corticosteroids and β2-agonists and this new knowledge may lead to elucidation of optimized corticosteroid-sparing therapies in the future.

Keywords: airway smooth muscle, corticosteroids, β2-agonists, PKA, PKIα, glucocorticoid-response elements

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common and increasingly prevalent chronic diseases in the world and is characterized by chronic airway inflammation, airflow obstruction, airway hyper-responsiveness and structural remodelling. Airway remodelling is considered to be a consequence of long-term inflammation. Airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells are a pivotal cell type in the development of airway remodelling, driving structural changes in the airway and being crucially involved in immunomodulatory processes through secretion of various pro-inflammatory molecules (Hirst, 2003; Black and Roth, 2009).

The MAPK superfamily of signalling molecules (p38 MAPK, JNK and ERK) have emerged as critical pathways that drive the development of airway remodelling to significantly contribute to asthma pathophysiology (Pelaia et al., 2005; Duan and Wong, 2006). When activated in ASM cells, our studies have shown that MAPKs can phosphorylate numerous downstream effectors, including transcription factors, cytoskeletal proteins and other phosphoproteins, to play a crucial role in a wide variety of pro-remodelling cellular functions, such as increased synthetic function, production of cytokines (Lalor et al., 2004; Henness et al., 2006; Quante et al., 2008) and pro-fibrotic proteins (Johnson et al., 2000; 2006; Ammit et al., 2007), and increased cell growth (Ammit et al., 2001; 2007; Lee et al., 2001; Burgess et al., 2008). Thus, inhibition of MAPKs has emerged as an attractive strategy for reversing inflammation and remodelling in asthma.

We focused our investigations on the endogenous MAPK deactivator – MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) – because MKP-1 is a critical negative regulator of the myriad pro-inflammatory pathways activated by MAPKs. We (Quante et al., 2008) and others (Issa et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2008) have discovered that the anti-inflammatory action of corticosteroids in ASM cells occurs in part via upregulation of MKP-1. Moreover, the corticosteroid-inducible gene MKP-1 is enhanced by long-acting β2-agonists (Kaur et al., 2008), and the increased expression of MKP-1 may explain the beneficial effects of β2-agonists/corticosteroid combination therapies in the repression of inflammatory gene expression in asthma (Giembycz et al., 2008; Kaur et al., 2008). Thus, a greater understanding of the molecular basis of MKP-1 regulation by asthmatic therapeutics is required as this new knowledge may lead to elucidation of optimized corticosteroid-sparing therapies in the future.

With this study, we showed that MKP-1 is a corticosteroid-inducible gene whose mRNA and protein expression in ASM cells is enhanced by a long-acting β2-agonist in an additive manner. Using PKIα overexpression, we provide direct evidence to confirm that PKA mediates MKP-1 regulation by the β2-agonist and collectively we showed that formoterol induces MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression in a cAMP-dependent manner via the classical β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway. Our studies also revealed that the crucial promoter region responsible for MKP-1 transcription induced by the corticosteroid dexamethasone is located between −1380 and −1266 bp of the human MKP-1 promoter; a region that contains a cis-acting corticosteroid-responsive region.

Methods

Cell culture

Human bronchi were obtained from patients undergoing surgical resection for carcinoma or lung transplant donors in accordance with procedures approved by the Central Sydney Area Health Service and the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney. ASM cells were dissected, purified and cultured as previously described by Johnson et al. (1995). A minimum of three different ASM primary cell lines were used for each experiment.

Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

MKP-1 mRNA expression

To examine the temporal kinetics of MKP-1 mRNA expression induced by the corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination, growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle, dexamethasone (100 nM), formoterol (10 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) in combination for 0, 5, 10 and 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 8 and 24 h. To demonstrate the role for the β2-adrenoceptor receptor-PKA pathway in β2-agonist-induced upregulation of MKP-1 mRNA expression, growth-arrested ASM cells were pretreated for 30 min with propranolol (0.1 µM), or for 60 min with H-89 (10 µM) or vehicle, before 1 h treatment with formoterol (10 nM). MKP-1 mRNA expression was quantified by real-time RT-PCR using an ABI Prism 7500 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and a MKP-1 primer set [Assays on Demand, dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1), Hs00610256_g1; Applied Biosystems] with a eukaryotic 18S rRNA endogenous control probe (Applied Biosystems) and subjected to the following amplification conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 1 cycle; 95°C for 10 min, 1 cycle; 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, 40 cycles.

MKP-1 Western blotting

To measure corticosteroid/β2-agonist-induced upregulation of MKP-1 protein, growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle, dexamethasone (100 nM), formoterol (10 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) in combination, and cells were lysed at 0 and 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 8 and 24 h. To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the upregulation of MKP-1 protein by formoterol, growth-arrested ASM cells were pretreated for 30 min with propranolol (0.1 µM), or for 60 min with H-89 (10 µM) or vehicle, then treated for 60 min with formoterol (10 nM). MKP-1 protein activation was quantified by Western blotting using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against MKP-1 (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), compared with α-tubulin as the loading control (mouse monoclonal IgG1, clone DM 1A; Santa Cruz). Primary antibodies were detected with goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit horse radish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA, USA). Densitometry was performed using ImageJ (Abramoff et al., 2004).

Adenoviral infection of PKIα

To confirm the involvement of the PKA pathway in the formoterol-induced upregulation of MKP-1, we utilized adenoviral overexpression of PKIα, a highly selective PKA inhibitor (Meja et al., 2004). ASM cells grown to approximately 70% confluence were incubated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's minimal essential medium plus 10% fetal calf serum media containing 300 multiplicity of infection (MOI) of either an empty adenoviral serotype 5 (Ad5) vector (null) or a PKIα Ad5 expression vector (Kaur et al., 2008). After 24 h, cells were fully confluent and were incubated in serum-free media overnight before the addition of vehicle, formoterol (10 nM), dexamethasone (100 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) in combination for 1 h. The effect of PKIα on MKP-1 mRNA expression was quantified by SYBR green real-time RT-PCR carried out on an ABI 7900HT instrument with amplification conditions as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 1 cycle; 95°C for 10 min, 1 cycle; 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, 40 cycles. A dissociation curve analysis was run after amplification was complete to determine primer specificity. Primer sequences used were MKP-1 (forward, 5′-GCTCAGCCTTCCCCTGAGTA-3′; reverse, 5′-GATACGCACTGCCCAGGTACA-3′); 18S rRNA (forward, 5′-CGGAGGTTCGAAGACGATCA-3′; reverse, 5′-GGCGGGTCATGGGAATAAC-3′); and PKIα (forward, 5′-CGTAACGCCATCCACGATATC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGCCAGTTCGTTTGAGTTTCC-3′). Expression of PKIα protein was confirmed by Western blotting using a goat polyclonal antibody (C-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and the effect of PKIα overexpression on MKP-1 protein was measured by Western blotting (both compared with α-tubulin as the loading control).

Transfection of MKP-1 promoter constructs

The pGL3 basic luciferase reporter vector containing an ∼3 kb fragment of the human MKP-1 gene promoter upstream of the transcription initiation site (−2975 to +247 bp) and a series of 5′-promoter deletion constructs (numbers refer to the position corresponding to transcriptional start site =+1), −2551 to +247; −2078 to +247; −1380 to +247; −1266 to +247; −2975 to +247 (Δ−1380 to −1266), were kindly provided by Professor Sam Okret (Karolinska Institutet, Sweden) (Johansson-Haque et al., 2008). To identify the MKP-1 promoter region responsible for corticosteroid responsiveness, transient transfection of ASM cells was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA), as previously described (Henness et al., 2004; Quante et al., 2008). Briefly, ASM cells were transfected for 24 h with 2.4 µg of the MKP-1 promoter constructs as well as 1.4 µg of pSV-β-galactosidase control vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to normalize transfection efficiencies. Cells were growth arrested and then treated with vehicle or dexamethasone (100 nM) for 24 h. Cells were then harvested and luciferase and β-galactosidase activities assessed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Results are expressed as MKP-1 promoter luciferase activity, relative to vehicle-treated cells (fold increase).

To determine the effects of the corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination, on MKP-1 promoter activity, ASM cells were transfected with the ∼3 kb human MKP-1 gene promoter (−2975 to +247 bp) and treated for 24 h with vehicle, formoterol (10 nM), dexamethasone (100 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) in combination, and luciferase activity was measured.

MKP-1 mRNA stability

To examine the stability of MKP-1 mRNA induced by the corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination, growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle, dexamethasone (100 nM), formoterol (10 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) for 1 h. Cells were then washed and incubated with actinomycin D (5 µg·mL−1) to inhibit further transcription (Quante et al., 2008). Total RNA was extracted following 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 and 3 h incubation with actinomycin D and MKP-1 mRNA expression was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. Results are presented as % mRNA remaining (i.e. in comparison to steady state levels of mRNA expression following 1 h of corticosteroid/β2-agonist treatment) after actinomycin D treatment.

Human antigen-R translocation

To measure dexamethasone-induced translocation of human antigen-R (HuR), growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle or dexamethasone (100 nM) for 1 h. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extraction was performed using NE-PER nuclear and cytosolic extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). HuR was quantified by Western blotting using a mouse monoclonal antibody against HuR (3A2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) compared with α-tubulin and a rabbit polyclonal antibody to lamin A/C (Cell Signaling Technology) as a loading control for the cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using either Student's unpaired t-test or two-way anova followed by Bonferroni's post-test. P values < 0.05 were sufficient to reject the null hypothesis for all analyses.

Results

The corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination, increase MKP-1 mRNA expression and protein upregulation

Because β2-agonists and corticosteroids are front line asthma therapies, we were interested in examining their effect, alone and in combination, on the upregulation of MKP-1 mRNA and protein in ASM cells.

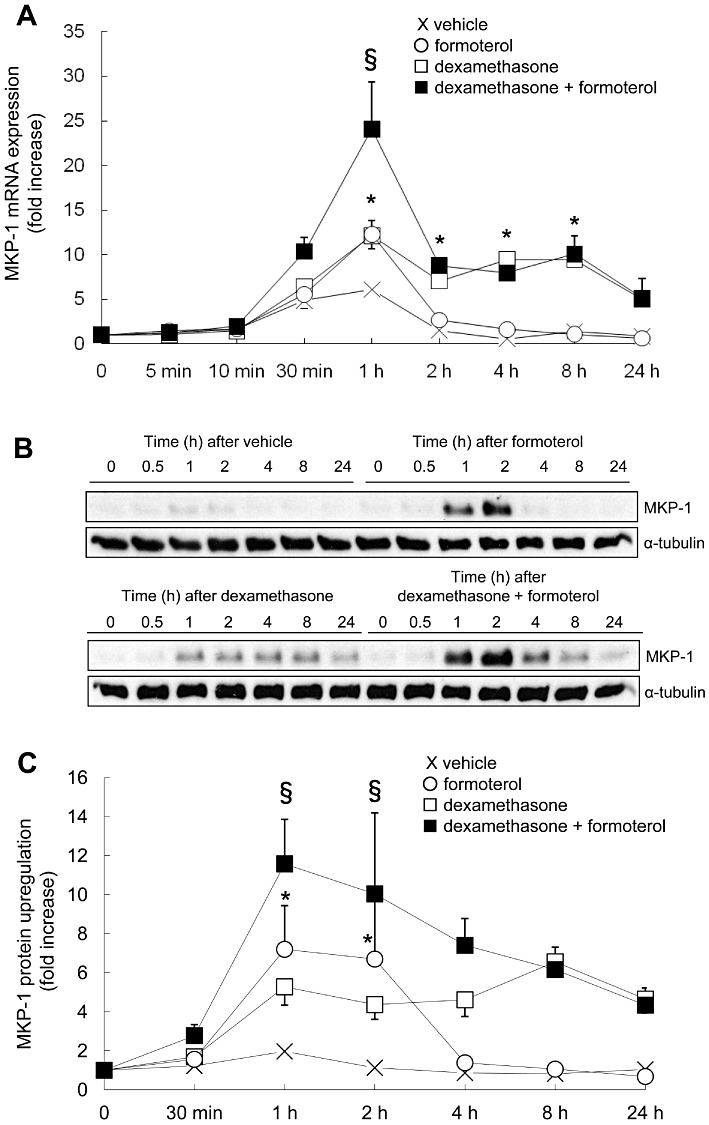

We first examined the temporal kinetics of MKP-1 mRNA expression induced by the corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination (Figure 1A). Growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle, formoterol (10 nM), dexamethasone (100 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) in combination. The concentrations used were chosen for the current study as they had been used previously in in vitro investigations of MKP-1 gene expression (Kaur et al., 2008). As demonstrated in Figure 1A, formoterol induced a transient increase in MKP-1 mRNA expression at 1 h (12.3 ± 1.5-fold: P < 0.05), which was significantly increased over the mRNA level observed in vehicle-treated cells. In contrast to the transient nature of the MKP-1 mRNA upregulation observed with the β2-agonist, the corticosteroid dexamethasone induced a significant 12.1 ± 2.5-fold (P < 0.05) increase in MKP-1 expression at 1 h, and this upregulation was sustained for up to 8 h (9.5 ± 1.7-fold: P < 0.05). When ASM cells were treated with dexamethasone and formoterol in combination, MKP-1 mRNA expression at 1 h was significantly increased to 24.1 ± 5.3-fold (P < 0.05) and then returned (by 2 h) to mRNA levels that were not significantly different from dexamethasone alone (Figure 1A). These results demonstrate that corticosteroids and β2-agonists in combination increase MKP-1 mRNA expression in an additive manner.

Figure 1.

The corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination, increase MKP-1 mRNA expression and protein upregulation. To examine the temporal kinetics of MKP-1 upregulation induced by corticosteroids and β2-agonists, alone and in combination, growth-arrested ASM cells were treated for the indicated times with vehicle (X), formoterol (10 nM), dexamethasone (100 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM). (A) MKP-1 mRNA expression was quantified by real-time RT-PCR and results expressed as fold increase over 0 min (mean + SEM values from n= 3–7 replicates). (B, C) MKP-1 protein was quantified by Western blotting, using α-tubulin as the loading control, where (B) illustrates representative Western blots, and (C) demonstrates densitometric analysis (results are expressed as fold increase over 0 min) (mean + SEM values from n= 3–5 replicates). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way anova then Bonferroni's post-test [where * indicates a significant effect of formoterol or dexamethasone on MKP-1, compared with vehicle-treated cells, and § indicates a significant effect of formoterol on dexamethasone-induced MKP-1 (P < 0.05)].

The MKP-1 protein results support the MKP-1 mRNA expression data. As shown in Figure 1B and C, formoterol induced a significant (P < 0.05), but transient, peak of protein at 1 and 2 h before MKP-1 protein levels decreased back to basal by 4 h. Densitometric analysis (Figure 1C) demonstrates that formoterol induced significant levels of MKP-1 protein, 7.2 ± 2.2-fold and 6.7 ± 3.2-fold at 1 and 2 h, respectively (P < 0.05). Confirming our previous findings (Quante et al., 2008), corticosteroid induced a sustained upregulation of MKP-1 protein for up to 24 h (Figure 1B & C). When ASM cells were treated with dexamethasone and formoterol in combination, the corticosteroid and β2-agonist also increased MKP-1 protein in an additive manner (Figure 1B & C), where formoterol significantly increased dexamethasone-induced MKP-1 protein upregulation at 1 h from 5.3 ± 0.9-fold to 11.6 ± 2.3-fold, and from 4.4 ± 0.7-fold to 10.0 ± 4.2-fold at 2 h (Figure 1C: P < 0.05). Taken together, these results demonstrate that corticosteroids and β2-agonists in combination increase MKP-1 mRNA expression and protein upregulation in an additive manner.

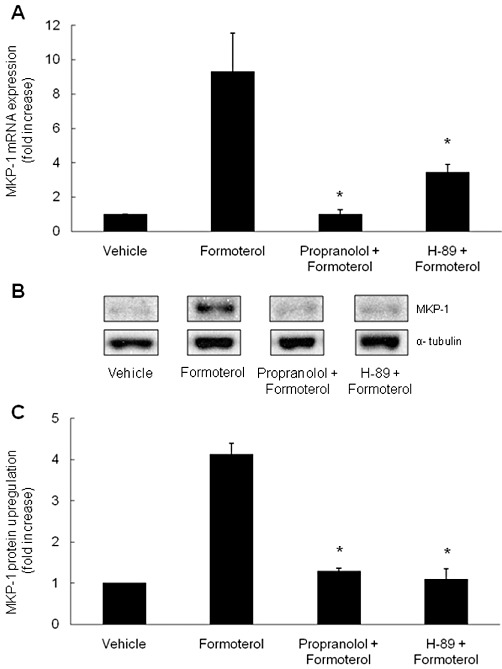

β2-agonist-induced MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression is upregulated in a cAMP-mediated manner via the β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway

To examine whether β2-agonists increase MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression via the classical β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway, ASM cells were treated with the β-adrenoceptor blocker propranolol (0.1 µM) or the non-specific PKA inhibitor H-89 (at 10 µM), before stimulation with formoterol (10 nM) for 1 h. Propranolol has been previously used to block β2-adrenoceptor-mediated signalling in ASM cells under these conditions (Roth et al., 2002) and H-89 can inhibit PKA activity in ASM cells, albeit non-specifically (Penn et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 2A, formoterol significantly increased MKP-1 mRNA expression to 9.3 ± 2.3-fold compared with vehicle-treated cells (P < 0.05). Formoterol-induced MKP-1 mRNA was significantly reduced by propranolol or H-89 to 1.0 ± 0.2-fold or 3.4 ± 0.5-fold, respectively (P < 0.05). There was no effect of propranolol or H-89 alone on MKP-1 mRNA (0.9 ± 0.1-fold or 0.9 ± 0.3-fold, respectively, compared with vehicle-treated cells). MKP-1 protein expression (as shown in Figure 2B) was in line with the mRNA data. Following densitometric analysis (demonstrated in Figure 2C), we show that formoterol significantly induced upregulation of MKP-1 protein by 4.1 ± 0.3-fold, compared with vehicle-treated cells (P < 0.05). Propranolol or H-89 significantly reduced formoterol-induced MKP-1 protein expression to levels that were not significantly different from vehicle-treated cells (to 1.3 ± 0.1-fold or 1.1 ± 0.3-fold respectively) (P < 0.05). Propranolol (1.4 ± 0.3-fold) or H-89 (1.2 ± 0.1-fold) added alone had no significant effect on MKP-1 protein upregulation.

Figure 2.

β2-agonist-induced MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression is upregulated in a cAMP-mediated manner via the β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway. To determine whether the β2-agonist formoterol increased MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression via the β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway, growth-arrested ASM cells were pretreated for 30 min with propranolol (0.1 µM), or 60 min with H-89 (10 µM) or vehicle, then treated with formoterol (10 nM) for 1 h. (A) MKP-1 mRNA was quantified by real-time RT-PCR and results expressed as fold increase over vehicle-treated cells. (B, C) MKP-1 protein was quantified by Western blotting (with α-tubulin as the loading control), where (B) illustrates a representative Western blot, and (C) demonstrates densitometric analysis (results expressed as fold increase over vehicle-treated cells). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's unpaired t test, where * denotes a significant effect on formoterol-induced MKP-1 (mean + SEM values from n= 4 replicates) (P < 0.05).

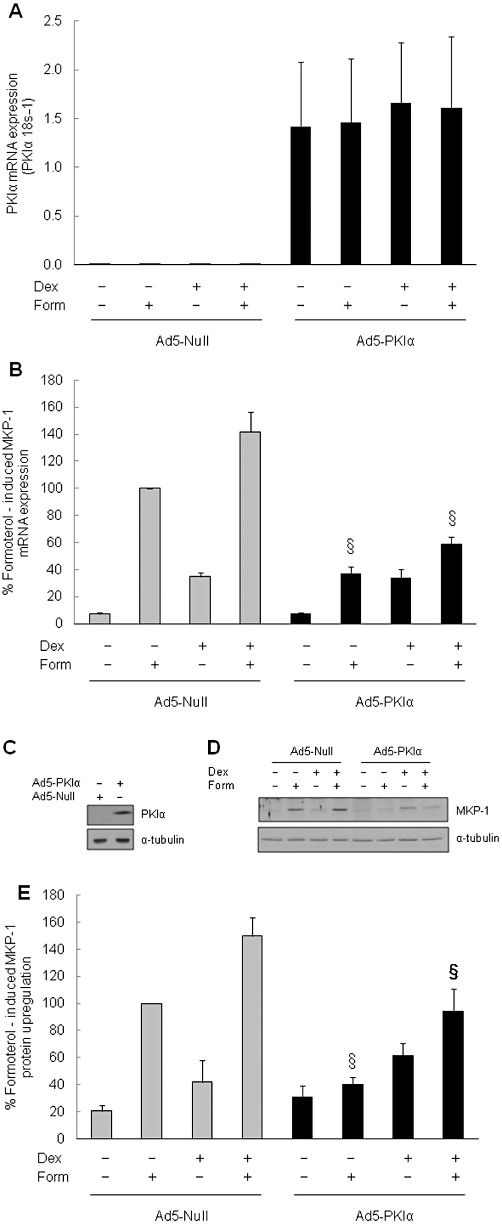

Because H-89 is non-specific (Penn et al., 1999), we confirmed the involvement of the PKA pathway by utilizing adenoviral overexpression of the highly selective PKA inhibitor – PKIα. ASM cells were infected with a MOI of 300 with either the empty vector (null) or an Ad5 expression vector that overexpresses PKIα. Figure 3A confirms the expression of PKIα mRNA in ASM cells infected with the Ad5-PKIα vector and no expression in the cells infected with the null vector. In the presence of PKIα, formoterol-induced MKP-1 mRNA expression was significantly repressed, compared with null-infected cells (Figure 3B: P < 0.05). While there was no effect on dexamethasone-induced MKP-1, there was a significant difference between the levels of MKP-1 induction in null-infected versus PKI-infected cells treated with formoterol in combination with dexamethasone (Figure 3B). The inhibition of formoterol-induced MKP-1 by PKIα was also demonstrated at the protein level (Figure 3D and E). Figure 3C confirms the overexpression of PKIα protein in ASM cells infected with Ad5-PKIα. Inhibiting PKA with PKIα significantly inhibited formoterol-induced MKP-1 protein upregulation by 59.8 ± 5.0%, compared with cells infected with the null vector (Figure 3E: P < 0.05). MKP-1 upregulation induced by formoterol and dexamethasone in combination was also significantly repressed in cells infected with PKIα (Figure 3D and E). These results demonstrate that formoterol-induced MKP-1 expression is PKA-mediated and, taken together, show that β2-agonist-induced MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression is upregulated in a cAMP-mediated manner via the β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway.

Figure 3.

Adenoviral overexpression of the selective PKA inhibitor, PKIα, represses formoterol-induced upregulation of MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression. To confirm the involvement of the PKA pathway in formoterol-induced MKP-1 mRNA expression and protein upregulation, ASM cells were infected at an MOI of 300 with either an empty Ad5 vector (Ad5-null) or a PKIα Ad5 expression vector (Ad5-PKIα). After 24 h, cells were fully confluent and were incubated in serum-free media overnight before the addition of vehicle, formoterol (form: 10 nM), dexamethasone (dex: 100 nM) or dex (100 nM) + form (10 nM) in combination for 1 h. (A) confirms overexpression of PKIα mRNA in cells infected with the PKIα-Ad5 expression vector, compared with null vector (results expressed as PKIα 18 s−1). (B) Demonstrates the repression of formoterol-induced MKP-1 mRNA by PKIα (results are expressed as percentage of formoterol-induced MKP-1 mRNA). (C) Confirms the overexpression of PKIα protein in cells infected with Ad5-PKIα, compared with Ad5-null. (D, E) Demonstrate the repression of formoterol-induced MKP-1 protein upregulation by PKIα, where (D) is a representative Western blot, and (E) shows densitometric analysis expressed as percentage of formoterol-induced MKP-1 protein. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's unpaired t-test, where § denotes a significant repressive effect of PKIα on formoterol-induced MKP-1 expression, both alone and in combination with dexamethasone [mean + SEM values from n= 6 replicates (mRNA) and n= 8 replicates (protein)] (P < 0.05).

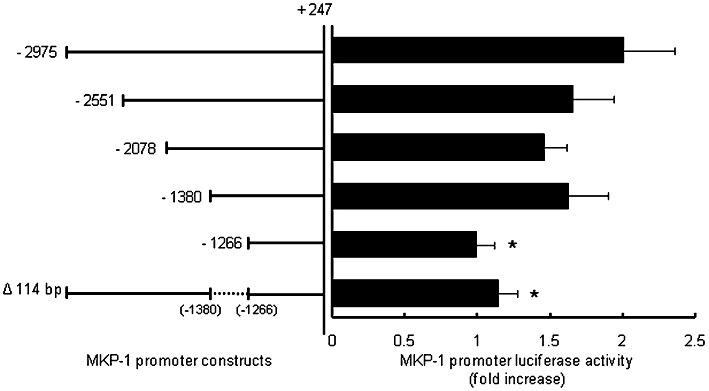

Dexamethasone activates MKP-1 transcription in ASM cells via a corticosteroid-responsive region located between −1380 and −1266 bp of the human MKP-1 promoter

Corticosteroids are known to induce MKP-1 gene expression; however, the human MKP-1 promoter does not contain the classical 15 bp glucocorticoid (GC)-responsive element (GRE) and it has only recently been shown to involve a more relaxed 10 bp cis-acting GC-responsive region (Tchen et al., 2010). To demonstrate that these promoter regions were responsible for activation of MKP-1 transcription by corticosteroids in ASM cells, we transiently transfected cells with a pGL3 basic luciferase reporter containing ∼3 kb of the human MKP-1 promoter (−2975 to +247 bp) and a series of 5′-promoter deletion constructs (Johansson-Haque et al., 2008) (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 4, dexamethasone significantly increased luciferase activity [by 2.0 ± 0.4-fold, compared with vehicle-treated cells (P < 0.05)] in ASM cells transfected with the reporter construct containing ∼3 kb of the human MKP-1 promoter (−2975 to +247 bp). There was no effect of dexamethasone on the pGL3 basic empty vector alone (data not shown). Successive deletions of the MKP-1 promoter from −2975 to −1380 bp had no effect on dexamethasone-induced luciferase activity, indicating that these promoter regions do not contain corticosteroid-responsive regions. However, further truncation of the 5′-promoter to −1266 bp showed a greatly reduced response to dexamethasone after corticosteroid treatment; luciferase activity was reduced to levels that were not significantly different from the vehicle-treated cells (1.0 ± 0.1-fold). This indicates that the sequence between −1380 and −1266 bp of the human MKP-1 promoter is required for responsiveness to corticosteroids in ASM cells. The importance of this promoter region was verified by transiently transfecting ASM cells with −2975 to +247 (Δ−1380 to −1266), a construct where the 114 bp region from −1380 to −1266 bp has been deleted from the ∼3 kb MKP-1 promoter. This deletion resulted in a significant loss of the response to dexamethasone (Figure 4: P < 0.05). Thus, dexamethasone activates MKP-1 transcription in ASM cells via a corticosteroid-responsive region located between −1380 and −1266 bp of the human MKP-1 promoter.

Figure 4.

Dexamethasone activates MKP-1 transcription in ASM cells via a corticosteroid-responsive region located between −1380 and −1266 bp of the human MKP-1 promoter. To identify the MKP-1 promoter region responsible for corticosteroid responsiveness, ASM cells were transiently transfected with a pGL3 basic luciferase reporter containing ∼3 kb of the human MKP-1 promoter (−2975 to +247 bp) and a series of 5′-promoter deletion constructs. Cells were treated with vehicle or dexamethasone (100 nM) for 24 h and results expressed as MKP-1 promoter luciferase activity, relative to vehicle-treated cells (fold increase). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's unpaired t-test where * denotes a significant effect of the promoter deletion on dexamethasone-induced luciferase activity (mean + SEM values from n= 8 replicates) (P < 0.05).

Additive effects of β2-agonists and corticosteroids occur at the transcriptional, rather than the post-transcriptional, level of MKP-1 gene expression

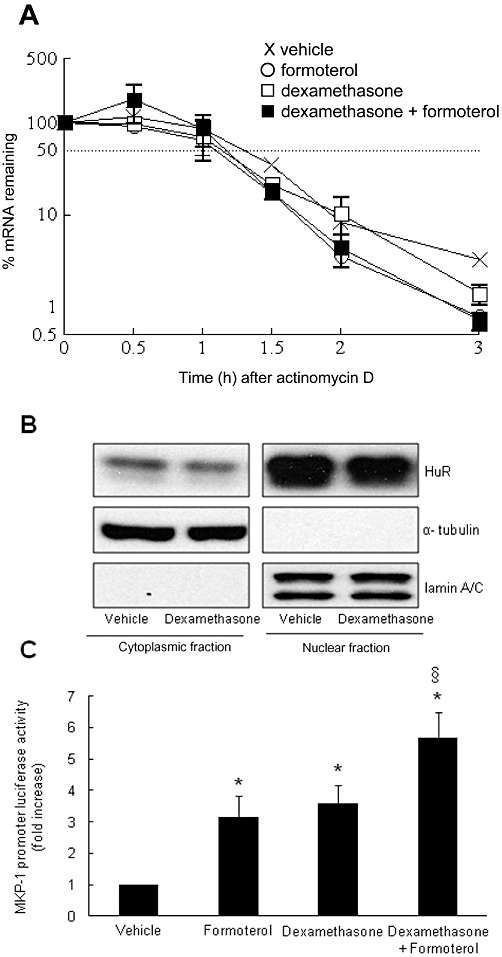

To date, most studies have focused on the transcriptional regulation of MKP-1, leaving post-transcriptional mechanisms, such as control of mRNA stability, largely unexplored. However, as transcriptional and post-transcriptional pathways act in concert to increase steady state mRNA levels, we investigated whether the asthma therapeutics regulate MKP-1 mRNA expression via post-transcriptional mechanisms in ASM cells. Growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle, dexamethasone (100 nM), formoterol (10 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) for 1 h. Transcription was then terminated using actinomycin D, and real-time RT-PCR was used to measure MKP-1 mRNA degradation over time to determine the kinetics of decay. As shown in Figure 5A, there was no difference between the results of the actinomycin D chase after ASM cells were treated with corticosteroids and β2-agonist, alone and in combination, in comparison to vehicle-treated cells. The rate of decay in ASM cells treated with the asthma therapeutics, as compared with vehicle-treated cells, was similar (Figure 5A) with a half-life for MKP-1 mRNA between 1 and 1.5 h.

Figure 5.

Additive effects of β2-agonists and corticosteroids occur at the transcriptional, rather than the post-transcriptional, level of MKP-1 gene expression. (A) To examine the stability of MKP-1 mRNA induced by the corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination, growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle, dexamethasone (100 nM), formoterol (10 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) for 1 h. MKP-1 mRNA stability was measured by actinomycin D chase using real-time RT-PCR and results expressed as % mRNA remaining over time. Data are mean + SEM values from n= 4 replicates. (B) To measure dexamethasone-induced translocation of HuR, growth-arrested ASM cells were treated with vehicle or dexamethasone (100 nM) for 1 h. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared and HuR protein measured by Western blotting, using α-tubulin and lamin A/C as the loading controls for the cytoplasmic or nuclear fractions respectively. (B) Illustrates a representative Western blot of n= 3 replicates. (C) To determine the effects of the corticosteroid dexamethasone and the β2-agonist formoterol, alone and in combination, on MKP-1 promoter activity, ASM cells were transfected with the ∼3 kb human MKP-1 gene promoter (−2975 to +247 bp) and treated for 24 h with vehicle, formoterol (10 nM), dexamethasone (100 nM) or dexamethasone (100 nM) + formoterol (10 nM) in combination. Luciferase activity was measured and results expressed as MKP-1 promoter luciferase activity, relative to vehicle-treated cells (fold increase). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's unpaired t-test where * denotes a significant effect of the asthma therapeutics on luciferase activity, compared with vehicle-treated cells, and § indicates a significant effect of formoterol + dexamethasone in combination on luciferase activity, compared with formoterol or dexamethasone treatment alone (mean + SEM values from n= 12 replicates for formoterol, n= 21 replicates for dexamethasone and n= 12 replicates for formoterol + dexamethasone) (P < 0.05).

As further confirmation, we examined the translocation of HuR – a stabilizing RNA binding protein. The 3′-untranslated region (3'-UTR) of the MKP-1 mRNA transcript contains multiple adenylate + uridylate-rich elements (Kwak et al., 1994) and a HuR binding motif (de Silanes et al., 2004). To be involved in the post-transcriptional regulation of a target mRNA, the nuclear protein HuR needs to translocate to the cytoplasm to be able to alter the mRNA stability. To investigate whether the RNA binding protein HuR is involved in MKP-1 mRNA stability, the subcellular localization of HuR was examined in vehicle- or dexamethasone- (100 nM) treated ASM cells. As shown in Figure 5B, the amount of HuR in the nuclear fraction of the cell lysates was unchanged and the cytoplasmic fraction did not show elevated levels of HuR after treatment with dexamethasone.

We then considered whether there was an additive effect of the asthma therapeutics on MKP-1 transcription. Growth-arrested ASM cells were transiently transfected with the ∼3 kb of the human MKP-1 promoter (−2975 to +247 bp) reporter construct and luciferase activity was measured after 24 h treatment with vehicle, formoterol (10 nM), dexamethasone (100 nM), or the corticosteroid and β2-agonist added in combination. As shown in Figure 5C, formoterol and dexamethasone alone significantly increase MKP-1 promoter activity by 3.6 ± 0.6-fold and 3.2 ± 0.7-fold, respectively (P < 0.05). After treatment with the corticosteroid and β2-agonist in combination, the resultant luciferase activity (5.7 ± 0.8-fold) was significantly greater than either asthma therapeutic added alone (P < 0.05). There was no effect of treatments on empty vector alone (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the additive effects of β2-agonists and corticosteroids occur at the transcriptional, rather than the post-transcriptional, level of MKP-1 gene expression.

Discussion

With this study, we extend our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids and β2-agonists. We demonstrated that the endogenous MAPK de-activator MKP-1 is a corticosteroid-inducible gene whose mRNA and protein expression in ASM cells is additively enhanced by a long-acting β2-agonist at the transcriptional, rather than the post-transcriptional, level of gene expression. The β2-agonist formoterol induced MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression in a cAMP-dependent manner via the classical β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway, while corticosteroids increased MKP-1 transcription via the recently described cis-acting corticosteroid-responsive region between −1380 and −1266 bp of the human MKP-1 promoter (Tchen et al., 2010).

MKP-1, the prototypical member of the MKP family, is a 367-amino acid protein expressed by an immediate-early gene (Sun et al., 1993). All MKPs contain a dual specificity phosphatase catalytic domain that directs dual dephosphorylation on the threonine and tyrosine residues of MAPKs (Farooq and Zhou, 2004). In ASM cells, our recent work has underscored the important anti-inflammatory role played by MKP-1; we have shown that corticosteroid-induced MKP-1 inhibits cytokine secretion by repressing p38-mediated mRNA stability (Quante et al., 2008), MKP-1 represses p38 MAPK activation in ASM cells from asthmatics (Burgess et al., 2008) and that increasing MKP-1 protein levels (by blocking its proteasomal degradation) represses multiple cytokines implicated in asthma (Moutzouris et al., 2010). More broadly, studies performed in MKP-1 knockout mice have confirmed that the inflammatory effects of dexamethasone are partly dependent on induction of MKP-1 (Abraham and Clark, 2006). Taken together, these results demonstrate that MKP-1 is an important anti-inflammatory molecule and a further understanding of how it is upregulated will help reveal strategies for harnessing its anti-inflammatory power in future pharmacotherapeutic strategies.

Our study builds on the knowledge that corticosteroid-induced MKP-1 gene expression is enhanced by long-acting β2-agonists in ASM cells (Kaur et al., 2008) and provides a greater understanding of the transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional signalling pathways responsible for MKP-1 upregulation by asthma therapeutics. We first examined the molecular mechanisms responsible for MKP-1 upregulation mediated by β2-agonists alone and showed that formoterol increased MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression. This transient upregulation was shown to be mediated by cAMP and occurred via the well-established β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway. The human MKP-1 promoter is known to contain two cis-acting cAMP response elements (Kwak et al., 1994; Sommer et al., 2000) and MKP-1 expression is cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) responsive (Cho et al., 2009). On examining PKA dependency, Cho et al. (2009) was unable to directly implicate PKA in CREB-mediated MKP-1 induction as they used H-89 as the only approach to inhibit PKA. In our study, we took two approaches towards inhibition of PKA: (i) we demonstrated that formoterol-induced MKP-1 expression can be attenuated by pretreatment with the non-specific inhibitor H-89; and then (ii) confirmed the involvement of PKA by adenoviral overexpression of the highly selective PKA inhibitor, PKIα. Our experiments with PKIα corroborate those obtained with H-89 and demonstrate that formoterol-induced MKP-1 mRNA expression and protein upregulation is PKA mediated. Thus, our study is the first to directly implicate PKA in the regulation of β2-agonist-induced MKP-1 expression.

Previously, the nature of MKP-1 transcriptional activation by corticosteroids was less well understood. The canonical pathway of corticosteroid-induced gene transcription involves interaction of the corticosteroid with the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). GRs can then dimerize and bind to the classical GRE on the 5′-promoter, a consensus DNA sequence defined as two inverted and imperfect repeats of the palindromic hexanucleotide TGTTCT separated by 3 bp spacer (GGTACANNNTGTTCT: where N is any base) (Beato, 1989; Newton, 2000). Although MKP-1 is a known corticosteroid-inducible gene (Kassel et al., 2001), the human MKP-1 promoter does not contain this classical 15 bp GRE (Kwak et al., 1994). Recent studies, however (So et al., 2007; 2008; Tchen et al., 2010), have revealed that the DNA-binding specificity of GR is somewhat more relaxed and that only 5 of the original 15 positions in the classical GRE are absolutely conserved (GGTACANNNTGTTCT) and consistently present at authentic GR binding sites in DNA. Thus, a more relaxed consensus sequence can be represented as a 10 bp binding motif with the 5 invariant bases required for corticosteroid responsiveness underlined GNACANNNNG (Tchen et al., 2010). Importantly, in the context of our current study using human MKP-1 promoter constructs, this 10 bp motif can be found between −1380 and −1266 bp of the human MKP-1 promoter, identifying the corticosteroid-responsive region responsible for the upregulation of MKP-1 transcription by dexamethasone in ASM cells. Our results are in accord with the results of studies by Johansson-Haque et al. (2008) and Tchen et al. (2010) and highlight the need for future studies to examine the corticosteroid-responsive region of the MKP-1 promoter in defined patient cohorts. Jin et al. (2010) recently conducted a pharmacogenetic analysis of the MKP-1 gene (aka DUSP1) relating corticosteroid responsiveness to single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in asthmatic patients. There was a relationship between some SNPs in the MKP-1 gene and inhaled corticosteroid response (Jin et al., 2010); although one SNP in the 5′ promoter region (357 bp proximal to the transcription start site) was found to be associated with clinical response, they comment that further studies examining polymorphisms upstream of this SNP, such as the corticosteroid-responsive regions in the MKP-1 promoter regions implicated by Johansson-Haque et al. (2008) and Tchen et al. (2010), may prove to be associated with clinical-inhaled corticosteroid response.

Finally, as MKP-1 mRNA expression has been shown (in cell types apart from ASM) to be upregulated by increased mRNA stability, we examined whether the sustained increase of MKP-1 induced by corticosteroids alone or in combination with β2-agonists was due to involvement of a post-transcriptional mechanism. Actinomycin D chase experiments revealed that there were no differences in the stability of the mRNA transcripts after treatment with the asthma therapeutics. Moreover, there were no differences in the cytoplasmic translocation of the nuclear protein HuR, a stabilizing RNA binding protein known to increase MKP-1 mRNA stability via its 3′-UTR (Kuwano et al., 2008). In contrast, the combination of dexamethasone and formoterol significantly enhanced MKP-1 promoter activity, demonstrating that the additive effects of β2-agonists and corticosteroids occur at the transcriptional, rather than the post-transcriptional, level of MKP-1 gene expression.

Demonstration of the molecular mechanisms underlying enhanced MKP-1 upregulation when β2-agonists and corticosteroids are added in combination provides a number of potential avenues for further research to optimize corticosteroid-sparing strategies in asthma. By identifying the corticosteroid-responsive region responsible for the upregulation of MKP-1 transcription by dexamethasone in ASM cells, a promoter region that contains the more relaxed cis-acting consensus sequence [10 bp binding motif with the 5 invariant bases (Tchen et al., 2010)], rather than the classical 15 bp GRE, our study joins others (Newton et al., 2010; Joanny et al., 2011) in informing future research endeavours designed to separate the desired anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids from their unwanted effects. The enhanced upregulation of the MAPK deactivator MKP-1 when β2-agonists and corticosteroids are used additively provides further supporting molecular mechanisms explaining the beneficial clinical effects of combination therapies in the repression of inflammatory gene expression in asthma (Giembycz et al., 2008; Kaur et al., 2008; Newton et al., 2010). More specifically, the demonstration that β2-agonists induced MKP-1 mRNA and protein expression in a cAMP-mediated manner via the β2-adrenoceptor-PKA pathway and additively enhanced corticosteroid-induced MKP-1 offers a number of potential strategies for future therapies designed to enhance the anti-inflammatory action of corticosteroids while reducing the required dose. These strategies could include tailored cAMP-elevating agents, combination therapies with phosphodiesterase 4A inhibitors or approaches targeting PKA (Wilson et al., 2009; Newton et al., 2010).

In summary, these results provide us with a greater understanding of the molecular basis of MKP-1 regulation by asthma therapeutics and reveal the transcriptional pathways responsible for the augmented expression of the corticosteroid-inducible gene MKP-1 by long-acting β2-agonists. The enhanced expression of the endogenous MAPK deactivator MKP-1 may explain the beneficial effects of long-acting β2-agonists/corticosteroid combination therapies in the repression of inflammatory gene expression in asthma.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a PhD scholarship to MM from the Senglet Stiftung (Switzerland), a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant to RN, a project grant (570856) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and a University of Sydney Thompson Fellowship to AJA. RN is an Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions Senior Scholar. The authors wish to thank Associate Professor Andrew R. Clark (Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology, Imperial College London) for helpful discussions; Professor Sam Okret (Karolinska Institutet) for generously providing the MKP-1 promoter constructs; and our colleagues in the Respiratory Research Group at the University of Sydney. We acknowledge the collaborative effort of the cardiopulmonary transplant team and the pathologists at St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney, and the thoracic physicians and pathologists at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Concord Repatriation Hospital, and Strathfield Private Hospital and Rhodes Pathology, Sydney.

Glossary

- Ad5

adenoviral serotype 5

- ASM

airway smooth muscle

- CREB

cyclic-AMP response element binding protein

- GC

glucocorticoid

- GRE

GC-responsive element

- H-89

N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide dihydrochloride

- MKP-1

MAPK phosphatase 1

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- 3'-UTR

3′-untranslated region

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Abraham SM, Clark AR. Dual-specificity phosphatase 1: a critical regulator of innate immune responses. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:1018–1023. doi: 10.1042/BST0341018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ammit AJ, Hastie AT, Edsall LC, Hoffman RK, Amrani Y, Krymskaya VP, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate modulates human airway smooth muscle cell functions that promote inflammation and airway remodeling in asthma. FASEB J. 2001;15:1212–1214. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0742fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammit AJ, Moir LM, Oliver BG, Hughes JM, Alkhouri H, Ge Q, et al. Effect of IL-6 trans-signaling on the pro-remodeling phenotype of airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:L199–L206. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00230.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato M. Gene regulation by steroid hormones. Cell. 1989;56:335–344. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JL, Roth M. Intrinsic asthma: is it intrinsic to the smooth muscle? Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:962–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess JK, Lee JH, Ge Q, Ramsay EE, Poniris MH, Parmentier J, et al. Dual ERK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways control airway smooth muscle proliferation: differences in asthma. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:673–679. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho IJ, Woo NR, Shin IC, Kim SG. H89, an inhibitor of PKA and MSK, inhibits cyclic-AMP response element binding protein-mediated MAPK phosphatase-1 induction by lipopolysaccharide. Inflamm Res. 2009;58:863–872. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0057-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silanes IL, Zhan M, Lal A, Yang X, Gorospe M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2987–2992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W, Wong WS. Targeting mitogen-activated protein kinases for asthma. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:691–698. doi: 10.2174/138945006777435353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq A, Zhou M-M. Structure and regulation of MAPK phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2004;16:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giembycz MA, Kaur M, Leigh R, Newton R. A Holy Grail of asthma management: toward understanding how long-acting beta(2)-adrenoceptor agonists enhance the clinical efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1090–1104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henness S, Johnson CK, Ge Q, Armour CL, Hughes JM, Ammit AJ. IL-17A augments TNF-α-induced IL-6 expression in airway smooth muscle by enhancing mRNA stability. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henness S, van Thoor E, Ge Q, Armour CL, Hughes JM, Ammit AJ. IL-17A acts via p38 MAPK to increase stability of TNF-α-induced IL-8 mRNA in human ASM. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1283–L1290. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00367.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst SJ. Regulation of airway smooth muscle cell immunomodulatory function: role in asthma. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;137:309–326. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa R, Xie S, Khorasani N, Sukkar M, Adcock IM, Lee K-Y, et al. Corticosteroid inhibition of growth-related oncogene protein-α via mitogen-activated kinase phosphatase-1 in airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:7366–7375. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Hu D, Peterson EL, Eng C, Levin AM, Wells K, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 1 as a pharmacogenetic modifier of inhaled steroid response among asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.007. e611–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joanny E, Ding Q, Gong L, Kong P, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Anti-inflammatory effects of selective glucocorticoid receptor modulators (SGRMs) are partially dependent on upregulation of dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) Br J Pharmacol. 2011;165:1124–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson-Haque K, Palanichamy E, Okret S. Stimulation of MAPK-phosphatase 1 gene expression by glucocorticoids occurs through a tethering mechanism involving C/EBP. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;41:239–249. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PR, Armour CL, Carey D, Black JL. Heparin and PGE2 inhibit DNA synthesis in human airway smooth muscle cells in culture. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1995;269:L514–L519. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.4.L514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PR, Burgess JK, Ge Q, Poniris M, Boustany S, Twigg SM, et al. Connective tissue growth factor induces extracellular matrix in asthmatic airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:32–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-703OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PRA, Black JL, Carlin S, Ge Q, Underwood PA. The production of extracellular matrix proteins by human passively sensitized airway smooth-muscle cells in culture: the effect of beclomethasone. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2145–2151. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.9909111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang BN, Jude JA, Panettieri RA, Jr, Walseth TF, Kannan MS. Glucocorticoid regulation of CD38 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of dual specificity phosphatase 1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L186–L193. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00352.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel O, Sancono A, Kratzschmar J, Kreft B, Stassen M, Cato ACB. Glucocorticoids inhibit MAP kinase via increased expression and decreased degradation of MKP-1. EMBO J. 2001;20:7108–7116. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur M, Chivers JE, Giembycz MA, Newton R. Long-acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists synergistically enhance glucocorticoid-dependent transcription in human airway epithelial and smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:203–214. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwano Y, Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Pullmann R, Jr, Martindale JL, Yang X, et al. MKP-1 mRNA stabilization and translational control by RNA-binding proteins HuR and NF90. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4562–4575. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00165-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak SP, Hakes DJ, Martell KJ, Dixon JE. Isolation and characterization of a human dual specificity protein-tyrosine phosphatase gene. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3596–3604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalor DJ, Truong B, Henness S, Blake AE, Ge Q, Ammit AJ, et al. Mechanisms of serum potentiation of GM-CSF production by human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:L1007–L1016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00126.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-H, Johnson PRA, Roth M, Hunt NH, Black JL. ERK activation and mitogenesis in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:L1019–L1029. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meja KK, Catley MC, Cambridge LM, Barnes PJ, Lum H, Newton R, et al. Adenovirus-mediated delivery and expression of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor gene to BEAS-2B epithelial cells abolishes the anti-inflammatory effects of rolipram, salbutamol, and prostaglandin E2: a comparison with H-89. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:833–844. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutzouris JP, Che W, Ramsay EE, Manetsch M, Alkhouri H, Bjorkman AM, et al. Proteasomal inhibition upregulates the endogenous MAPK deactivator MKP-1 in human airway smooth muscle: mechanism of action and effect on cytokine secretion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:416–423. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid action: what is important? Thorax. 2000;55:603–613. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.7.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R, Leigh R, Giembycz MA. Pharmacological strategies for improving the efficacy and therapeutic ratio of glucocorticoids in inflammatory lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125:286–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaia G, Cuda G, Vatrella A, Gallelli L, Caraglia M, Marra M, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and asthma. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:642–653. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn RB, Parent JL, Pronin AN, Panettieri RA, Jr, Benovic JL. Pharmacological inhibition of protein kinases in intact cells: antagonism of beta adrenergic receptor ligand binding by H-89 reveals limitations of usefulness. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:428–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quante T, Ng YC, Ramsay EE, Henness S, Allen JC, Parmentier J, et al. Corticosteroids reduce IL-6 in ASM cells via up-regulation of MKP-1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:208–217. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0014OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth M, Johnson PRA, Rüdiger JJ, King GG, Ge Q, Burgess JK, et al. Interaction between glucocorticoids and β2 agonists on bronchial airway smooth muscle cells through synchronised cellular signalling. Lancet. 2002;360:1293–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So AY, Chaivorapol C, Bolton EC, Li H, Yamamoto KR. Determinants of cell- and gene-specific transcriptional regulation by the glucocorticoid receptor. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e94. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So AY, Cooper SB, Feldman BJ, Manuchehri M, Yamamoto KR. Conservation analysis predicts in vivo occupancy of glucocorticoid receptor-binding sequences at glucocorticoid-induced genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5745–5749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801551105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer A, Burkhardt H, Keyse SM, Luscher B. Synergistic activation of the mkp-1 gene by protein kinase A signaling and USF, but not c-Myc. FEBS Lett. 2000;474:146–150. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Charles CH, Lau LF, Tonks NK. MKP-1 (3CH134), an immediate early gene product, is a dual specificity phosphatase that dephosphorylates MAP kinase in vivo. Cell. 1993;75:487–493. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchen CR, Martins JRS, Paktiawal N, Perelli R, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Glucocorticoid regulation of mouse and human dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) genes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2642–2652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Shen P, Rider CF, Traves SL, Proud D, Newton R, et al. Selective prostacyclin receptor agonism augments glucocorticoid-induced gene expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:6788–6799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]