Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Voltage-gated sodium channels are expressed primarily in excitable cells and play a pivotal role in the initiation and propagation of action potentials. Nine subtypes of the pore-forming α-subunit have been identified, each with a distinct tissue distribution, biophysical properties and sensitivity to tetrodotoxin (TTX). Nav1.8, a TTX-resistant (TTX-R) subtype, is selectively expressed in sensory neurons and plays a pathophysiological role in neuropathic pain. In comparison with TTX-sensitive (TTX-S) Navα-subtypes in neurons, Nav1.8 is most strongly inhibited by the µO-conotoxin MrVIB from Conus marmoreus. To determine which domain confers Nav1.8 α-subunit its biophysical properties and MrVIB binding, we constructed various chimeric channels incorporating sequence from Nav1.8 and the TTX-S Nav1.2 using a domain exchange strategy.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Wild-type and chimeric Nav channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes, and depolarization-activated Na+ currents were recorded using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique.

KEY RESULTS

MrVIB (1 µM) reduced Nav1.2 current amplitude to 69 ± 12%, whereas Nav1.8 current was reduced to 31 ± 3%, confirming that MrVIB has a binding preference for Nav1.8. A similar reduction in Na+ current amplitude was observed when MrVIB was applied to chimeras containing the region extending from S6 segment of domain I through the S5-S6 linker of domain II of Nav1.8. In contrast, MrVIB had only a small effect on Na+ current for chimeras containing the corresponding region of Nav1.2.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Taken together, these results suggest that domain II of Nav1.8 is an important determinant of MrVIB affinity, highlighting a region of the α-subunit that may allow further nociceptor-specific ligand targeting.

Keywords: electrophysiology, heterologous expression, Xenopus oocytes, chimera, µO-conotoxin MrVIB, tetrodotoxin, voltage-gated sodium channels, Nav1.2, Nav1.8

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) are expressed in central and peripheral neurons, as well as skeletal, cardiac and smooth muscle cells. These large transmembrane proteins act as molecular pores for Na+ ion influx to depolarize the resting membrane of excitable cells to initiate and propagate action potentials (Hille et al., 1999). VGSCs consist of a pore-forming, ion-conducting α-subunit and one or more auxiliary β-subunits. To date, nine mammalian VGSCs α-subunit isoforms (Nav1.1–1.9) and four β-subunits have been identified (Hartshorne et al., 1982; Hartshorne and Catterall, 1984; Catterall, 2000; Morgan et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2003). The α-subunit consists of a 260 kDa transmembrane protein comprising four homologous domains (domains I–IV), with each domain containing six transmembrane-spanning helices (S1–S6). Structure–function studies of the α-subunit have shown that the S4 segment in each domain serves as voltage sensor for channel activation (Noda et al., 1984; Catterall, 2000; Yu and Catterall, 2003), whereas fast inactivation is mediated by the motif located at the loop connecting domains III and IV to occlude the channel pore following activation (Nguyen and Goldin, 2010). The hairpin-like S5-S6P loops from each domain form the outer half of the channel pore, whereas S6 transmembrane domains form the inner half of the channel pore. The α-subunit isoform is a major determinant of VGSC tissue distribution, biophysical properties and sensitivity to the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin (TTX) (Ekberg and Adams, 2006a), which contributes to their diversity of physiological functions.

Apart from their physiological role in excitable cells, VGSC gain-of-function mutations are associated with several clinical disorders, like epilepsy (Mulley et al., 2003; Gourfinkel-An et al., 2004), myotonia (Jurkat-Rott and Lehmann-Horn, 2005) and chronic pain (Waxman et al., 1999; Wood et al., 2004). VGSC Nav1.8, a TTX-resistant (TTX-R) subtype, is expressed predominately in sensory neurons (Akopian et al., 1996; 1999; Djouhri et al., 2003), and is thought to play a major role in pain pathways. Nav1.8 knockout mice display attenuated pain behaviour in response to noxious stimuli compared with wild-type mice (Akopian et al., 1999). The TTX-sensitive (TTX-S) VGSC subtype Nav1.2 is predominately expressed in the CNS (Goldin, 2001) and mutations in this channel are associated with inherited epilepsies, including benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures (Misra et al., 2008). Given the critical role of VGSCs in various pathological conditions, there is considerable interest in finding isoform-specific VGSC antagonists that may have potential therapeutic benefits for VGSC dysfunction.

Conotoxins are peptides from the venom of cone snails and are a rich source of ion channel/transporter modulators. Some conotoxins have been identified as selective inhibitors of VGSCs. δ-Conotoxins delay or inhibit fast inactivation of VGSCs, whereas µ-conotoxins block the channel pore (Li et al., 2003; Li and Tomaselli, 2004; Terlau and Olivera, 2004; Leipold et al., 2005). In contrast, conotoxins of the µO-family inhibit Na+ currents in Nav1.4 by hindering the voltage sensor in domain II from activating and, hence, the channel from opening (Leipold et al., 2007). µO-conotoxins are of interest since they block TTX-R Na+ channels, particularly Nav1.8, and have been shown to exert an anti-nociceptive effect in animal pain models (Bulaj et al., 2006; Ekberg et al., 2006b). Given this effect, µO-conotoxins have the potential to serve as a lead in the development of new analgesics.

To date, two closely related µO-conotoxins, MrVIA and MrVIB, from the venom of Conus marmoreus, have been identified that differ in only 3 of their 31 residues (Fainzilber et al., 1995; McIntosh et al., 1995). Both µO-conotoxins block TTX-R Na+ currents in mammalian dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (Daly et al., 2004; Bulaj et al., 2006; Ekberg et al., 2006b). Analysis of their binding site in rat Nav1.4 channels identified the C-terminal pore loop of domain III as necessary for MrVIA binding (Zorn et al., 2006). In contrast, a later study using site-directed mutagenesis of Nav1.4 revealed that the voltage sensor in domain II is the main toxin binding site (Leipold et al., 2007). Due to the considerable interest in Nav1.8 channels as potential targets for selective analgesia, we constructed chimeras from TTX-R Nav1.8 and the TTX-S Nav1.2 isoform to examine effects of the domains of Nav1.8 α-subunit on channel properties and sensitivity to µO-conotoxin MrVIB. Here, we use cloned channels exogenously expressed in Xenopus oocytes to demonstrate that a key binding site associated with the high-affinity interactions of µO-conotoxins with Nav1.8 is located in the region extending from S6 of domain I through the S5-S6 linker of domain II of Nav1.8.

Methods

MrVIB synthesis and construction of the α-subunit chimeras

MrVIB conotoxin was synthesized as described previously (Daly et al., 2004). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on rat Nav1.2/pcDNA3.1 and human Nav1.8/pcDNA3.1 constructs using the QuikChange® II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Invitrogen, Mulgrave, VIC, Australia). Naturally occurring restriction enzyme (RE) sites were selected from the Nav1.8 sequence to generate useful switch points for generating chimeras. Corresponding RE sites were added and/or deleted from Nav1.2/pcDNA3.1 and Nav1.8/pcDNA3.1 constructs to facilitate digestion and re-ligation of chosen regions. A Sbf I site was introduced at position 3010 of the Nav1.2 sequence. The 8822 chimera was constructed by ligating domain III and domain IV from Nav1.2 with domain I and domain II of Nav1.8/pcDNA3.1 (Sbf I/Not I digest). The 2288 chimera was constructed by ligating domain III and domain IV from Nav1.8 with domain I and domain II from Nav1.2/pcDNA3.1 (Sbf I/Xho I digest). Two Mab I (isoschizomer of Sex AI) sites were introduced at positions 1250 and 2920 of the Nav1.2 sequence, and two vector Mab I sites were removed from Nav1.8/pcDNA3.1. The 8288 chimera was constructed by ligating the Nav1.2 Mab I fragment into Nav1.8/pCDNA3.1. An Nde I site was introduced at position 2870 of the Nav1.2 sequence. An Nde I site was also deleted from the vector sequence for Nav1.2/pcDNA3.1 and Nav1.8/pCDNA3.1. The 8/2288 chimera was constructed by inserting the Nav1.2 Nde I fragment into Nav1.8/pcDNA3.1. The 2/8822 chimera was constructed by inserting the Nav1.8 Nde I fragment into Nav1.2/pcDNA3.1. A Bsr GI site was deleted from position 330, and an additional Bsr GI site was introduced at position 4340 of the Nav1.2 sequence. The 8882 chimera was constructed by inserting the Nav1.2 Bsr GI fragment into Nav1.8/pcDNA3.1.

The resultant ligation reactions from the above combinations were used to transform chemically competent TOP10 E. coli cells (Invitrogen). DNA was prepared from antibiotic resistant colonies using a QIAprep plasmid miniprep kit (QIAGEN Pty Ltd, Doncaster, VIC, Australia). Chimera junctions were checked for correct α-subunit switching by DNA sequencing.

Oocyte extraction

Stage V-VI oocytes were harvested from sexually mature female Xenopus laevis anaesthetized with 0.1% tricaine (3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester), following protocols approved by the RMIT University Animal Ethics Committee. The oocytes were defolliculated in collagenase (1.5 mg·ml−1) and dissolved in calcium-free solution (in mM: 82.5 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2 and 5 HEPES (NaOH) at pH 7.4) before RNA injection. The results of all studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

RNA preparation and injection in Xenopus oocytes

Constructs encoding human Nav1.8 (cloned into pcDNA3.1), rat Nav1.2 (cloned into pcDNA3.1) and chimeras (pcDNA3.1) were linearized, and cRNA was synthesized using a T7 RNA polymerase in vitro transcription kit (mMESSAGE mMachine; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). All cRNAs were produced in parallel under the same protocol to maximize consistency in concentration and purity. cRNA concentration was measured spectrophotometrically and adjusted to 5 ng for injection in Xenopus laevis oocytes, with the exception of Nav1.2 and chimera 8822, where oocytes were injected with 0.25 ng and 0.5 ng cRNA, respectively, to obtain currents of similar amplitude. All constructs were expressed in the absence of β subunits. Injected oocytes were incubated for 2−5 days at 18°C in ND98 solution containing 96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM HEPES(NaOH) at pH 7.4, supplemented with pyruvate (5 mM) and gentamycin (50 µg·mL−1).

Oocyte electrophysiology

Oocytes were transferred to a 50 µL volume recording chamber and gravity perfused at 1.5–2.5 mL·min−1 with ND96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM HEPES(NaOH) at pH 7.4). Two-electrode (virtual ground circuit) voltage clamp experiments were performed at room temperature (21–23°C) with a GeneClamp 500B amplifier (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and pCLAMP 8 software (Molecular Devices). Micropipettes pulled from glass capillaries (3-000-203 GX, Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA, USA) and filled with 3 M KCl had tip resistances of 0.3 to 1.5 MΩ. Whole-cell Na+ currents were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and leak currents subtracted online using a −P/6 protocol. MrVIB and TTX (Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia) were diluted to the appropriate final concentrations by applying the toxins directly to the bath solution. Peak current amplitude was measured before and after a 2 min incubation of the toxins.

Data analysis

All data were analyzed offline using Clampfit 10 software (Molecular Devices). Mathematical formulas are described below. The voltage-dependence of activation was determined by measuring the amplitude of the Na+ current elicited by depolarization to various membrane potentials. Voltage-dependent Na+ conductance (G) was determined from transformations of current–voltage relationship (I–V) curves using the formula

| (1) |

where I is the peak current amplitude, V the test membrane potential and Vr the measured or extrapolated reversal potential. Current activation curves were fitted with a sigmoidal Boltzmann function that identifies the voltage at which the VGSC is half-maximally activated:

| (2) |

where G represents the conductance at various membrane potentials, G0 the peak conductance, V1/2act the voltage where VGSCs are half-maximally activated, V is the depolarized membrane potential and KVact the slope constant.

Steady-state inactivation at various membrane potentials was determined using a two-pulse protocol in which oocytes were depolarized from a holding potential of −110 mV to various conditioning prepulse potentials ranging from −110 mV to +50 mV for 550 ms, immediately followed by a test pulse to +10 mV. Current amplitudes elicited during the test pulse were normalized to the amplitude elicited after a prepulse from −110 mV, where steady-state inactivation is minimal. Inactivation curves were fitted with a single Boltzmann function:

| (3) |

where I/I0 represents the fraction of current available, V1/2 the voltage where the VGSCs are half-maximally inactivated, V the depolarized membrane potential and Kv the slope constant. All data are presented as mean ± SEM with n representing the number of oocytes tested.

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as the mean ± SEM. The statistical significance among groups was evaluated by using anova, followed by Holm–Sidiak's post hoc test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

All drug/target nomenclature conforms to the British Journal of Pharmacology's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2011).

Results

Biophysical characterization of Nav1.2 and Nav1.8

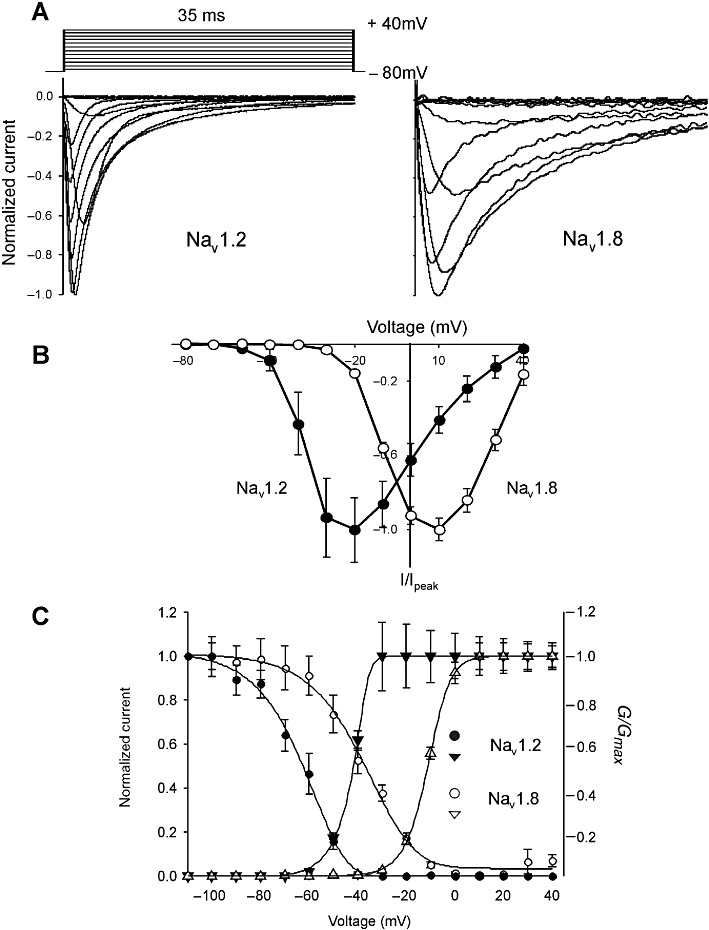

Initial experiments characterized the biophysical properties of the parent Nav1.2 and Nav1.8 channel isoforms functionally expressed in Xenopus oocytes to demonstrate isoform-specific differences in kinetic and activation-inactivation properties. Figure 1A shows representative whole-cell current traces for Nav1.2 and Nav1.8 in response to depolarization voltage steps from −80 mV to +40 mV in increments of 10 mV. Nav1.8 produced a slowly inactivating Na+ current that persisted in the presence of 1 µM TTX, whereas the current mediated by Nav1.2 exhibited fast activation and inactivation kinetics, and was completely inhibited by 1 µM TTX (Figure 1A, Figure 5A).

Figure 1.

Depolarization-activated Na+ currents elicited in Xenopus oocytes expressing Nav1.2 and Nav1.8. (A) Representative normalized depolarization-activated Na+ currents in oocytes expressing Nav1.2 and Nav1.8. Oocytes were held at −80 mV and depolarized to membrane potentials ranging from −80 to +40 mV in 10 mV increments. (B) Current–voltage relationships obtained for Nav1.2 and Nav1.8. Oocytes were depolarized to voltages ranging from −80 to +40 mV in 10 mV increments, from a holding potential of −80 mV. Normalized peak currents (I/Imax) of Nav1.2 (n= 15) and Nav1.8 (n= 23) plotted as a function of membrane voltage. (C) Voltage-dependence of inactivation. Oocytes were held at −110 mV before a 550 ms conditioning pre-pulse was applied to potentials ranging from −110 to +50 mV, followed immediately by a depolarizing pulse to +10 mV. Data are represented as the Na+ current amplitude recorded after a pre-pulse to different voltages (I) relative to the Na+ current amplitude recorded after a pre-pulse from −110 mV. Voltage-dependence of activation was determined by applying depolarizing pulses from a holding potential of −80 mV to potentials ranging from −80 mV to +40 mV in 10 mV increments. Voltage-dependent Na+ conductance (G) was determined from transformations of current–voltage relationship (I–V) curves. Data obtained for Nav1.2 (n= 20); Nav1.8 (n= 27) are represented as mean ± SEM.

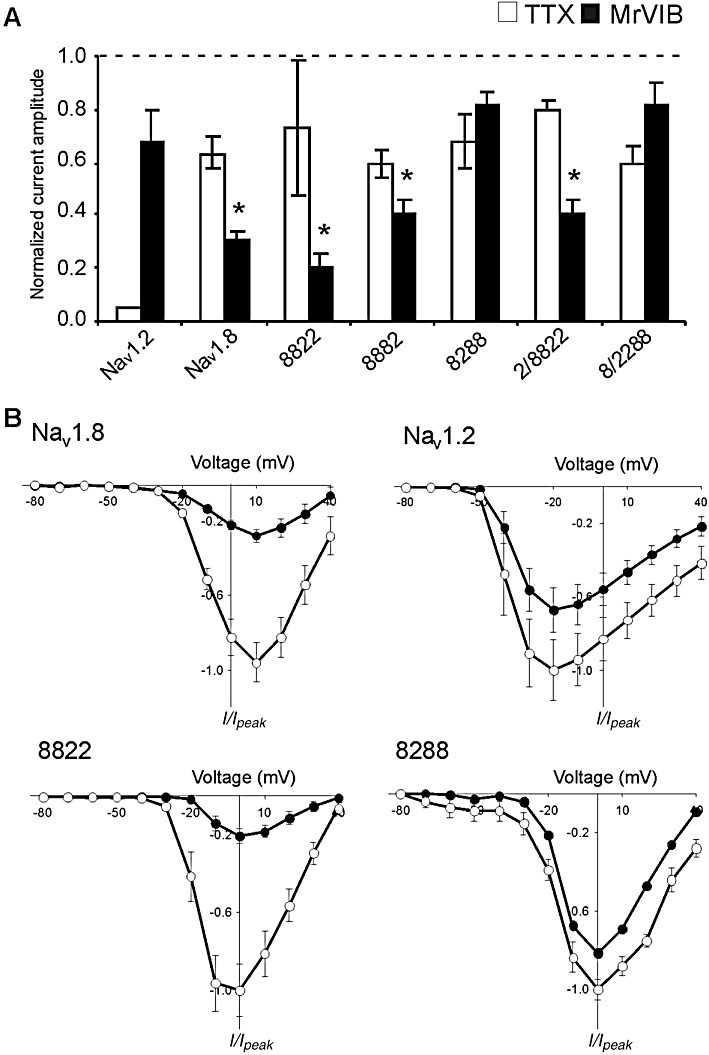

Figure 5.

Effects of µO-MrVIB and TTX on maximal Na+ current amplitude of Nav1.2, Nav1.8 and their chimeras. (A) Histogram representing the maximal Na+ current amplitude of oocytes expressing Nav1.2, Nav1.8 or their chimeras, in the presence of either 1 µM MrVIB or TTX (1 µM for Nav1.2; 100 µM for Nav1.8 and chimeras) relative to control (absence of MrVIB or TTX). Data are presented as mean ± SEM for at least 5 oocytes (*MrVIB versus control, P < 0.05; TTX inhibition of Nav1.8 and chimeras were all significant compared with Nav1.2, P < 0.001). (B) Current–voltage relationship of Nav1.2, Nav1.8 and chimera 8288 and 8822 in the absence (open symbols) and presence (solid symbols) of 1 µM MrVIB. Oocytes were depolarized to voltages from −80 to +40 mV in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of −80 mV. Normalized peak currents (I/I0) were plotted as a function of membrane potential. Data represent mean ± SEM obtained for Nav1.8 (n= 9/9), Nav1.2 (n= 7/7), 8288 (n= 5/5) and 8822 (n= 6/6).

Normalized peak currents (I/Imax) of each channel were plotted as a function of membrane voltage. Figure 1B illustrates the I–V curves of both channels. Peak Na+ current was activated at a command potential of +10 mV for the TTX-R Nav1.8 and −20 mV for TTX-S Nav1.2. To quantify the kinetics between Nav1.2 and Nav1.8, inactivation time constants (τinact) were fitted by a single exponential equation. The voltage used for fitting τact and τinact was usually −10 mV before peak current was reached. The τinact and τact for Nav1.2 was 2.5 ± 0.1 ms (n= 7) and 0.7 ± 0.04 ms (n= 12), respectively, both of which were considerably faster than the values for Nav1.8 (τinact= 6.6 ± 0.1 ms; τact= 1.4 ± 0.04 ms; n= 15).

There were also clear differences between Nav1.2 and Nav1.8 voltage-dependence of inactivation and activation. The voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation was determined by applying a 550 ms conditioning prepulse of varying magnitude, then a test pulse to +10 mV. Steady-state voltage-dependence of activation was found by applying a series of depolarizing voltage steps between −80 and +40 mV in 10 mV steps. Conductance (G) was calculated from peak currents and G-V activation and inactivation curves fitted by a single Boltzmann function (Figure 1C; Table 1). Both the half-maximal voltage-dependence of inactivation (V1/2inact) and activation (V1/2act) were more positive for Nav1.8 than Nav1.2 (Table 1). Together, the voltage-dependent properties and kinetics for Nav1.8 and Nav1.2 demonstrate isoform-specific differences that are comparable with previously published data (Sangameswaran et al., 1997; Smith and Goldin, 1998; Smith et al., 1998; Fahmi et al., 2001).

Table 1.

Voltage-dependence and kinetics of Nav1.2, Nav1.8 and chimeras

| α-Subunits | Chimeras | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Nav1.2 | Nav1.8 | 8822 | 8288 | 2/8822 | 8/2288 | 8882 |

| Vrev (mV) | 42.0 ± 3.6 (7) | 41.6 ± 1.2 (18) | 39.9 ± 1.0 (16) | 45.6 ± 3.7 (13) | 44.7 ± 1.5 (32) | 47.4 ± 2.9 (14) | 45.8 ± 1.9 (20) |

| V0.5act (mV) | −33.0 ± 0.7 (7) | −3.0 ± 0.8 (18) | −17.8 ± 1.9 (16) | −12.5 ± 2.5 (13) | 4.9 ± 1.2 (32) | −17.5 ± 1.3 (14) | −2.4 ± 0.8 (20) |

| τact (ms) | 0.7 ± 0.04 (12) | 1.4 ± 0.04 (15) | 1.2 ± 0.1 (16) | 1.0 ± 0.03 (10) | 1.2 ± 0.03 (18) | 0.8 ± 0.1 (12) | 2.8 ± 0.04 (19) |

| V0.5inact (mV) | −63.0 ± 0.9 (20) | −38.4 ± 1.0 (27) | −39.1 ± 1.8 (15) | −39.0 ± 0.7 (11) | −37.5 ± 0.6 (16) | −47.5 ± 0.5 (10) | −35.0 ± 0.8 (16) |

| τinact (ms) | 2.5 ± 0.03 (7) | 6.6 ± 0.03 (15) | 6.7 ± 0.2 (16) | 5.7 ± 0.04 (10) | 15.3 ± 0.2 (10) | 3.4 ± 0.3 (11) | 14.1 ± 0.2 (5) |

Values are presented as mean ± SEM. The number of oocytes is given in parentheses. The amplitude of Na+ currents recorded for chimera 8822 was insufficient for detailed analysis and not included.

Biophysical characterization of Nav1.2/Nav1.8 chimeras

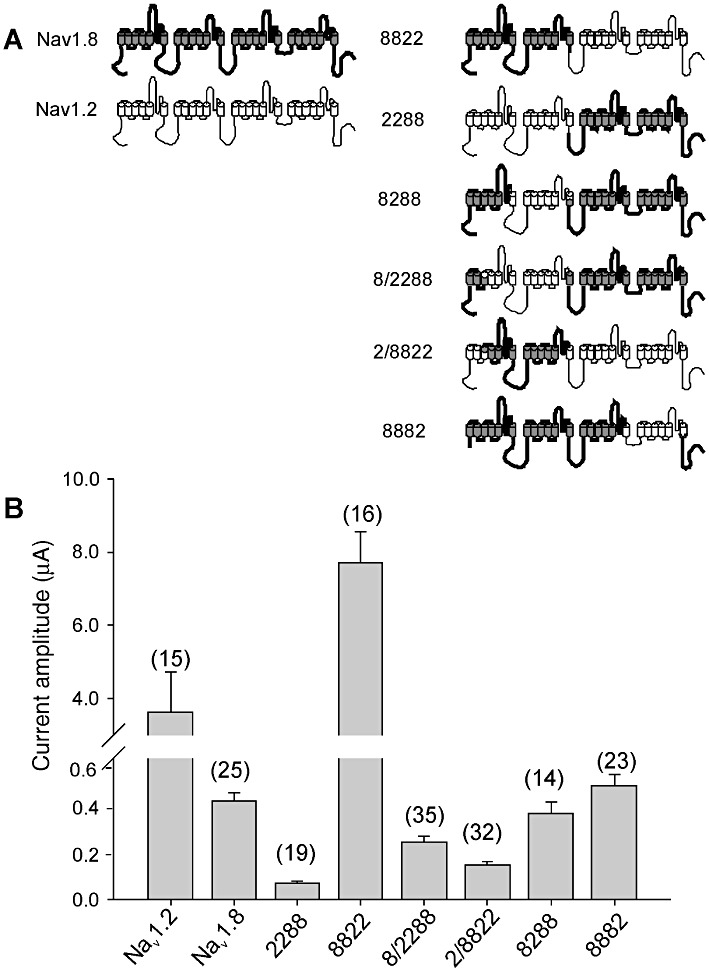

Chimeras were constructed by substituting regions of Nav1.8 with the same regions from Nav1.2 (Figure 2A). Each domain of the chimera was designated by a number that indicated the parent channel making the major contribution to each of the four domains. For example, chimera 8288 was constructed by substituting S6 segment of domain I and domain II of Nav1.8 with the corresponding regions of Nav1.2. Chimera 8/2288 was constructed by substituting the region from segment S3 of domain I to the linker of segment S5-S6 of domain II with the corresponding region of Nav1.2 (Figure 2A). The chimera 2/8822 construct was the reverse of 8/2288. Segment S6 of domain III and domain IV of Nav1.8 were replaced with the corresponding regions from Nav1.2 to produce chimera 8882 (Figure 2A). Chimeric channels 8822 and 2288 were constructed by exchanging half of each isoform (Figure 2A). The biophysical properties of the six chimeras were characterized in two-electrode voltage clamp experiments in Xenopus oocytes and compared with the parent channels, Nav1.2 and Nav1.8.

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic diagram of VGSC α-subunits illustrating the chimeras formed from the parent Nav1.8 (shaded) and Nav1.2 (open) subunits. Each of the four domains and 6 transmembrane segments of the α-subunits are shown. (B) Histogram of peak Na+ current amplitudes of Nav1.2, Nav1.8 and chimeras expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Data represent means ± SEM of n values indicated on the histogram.

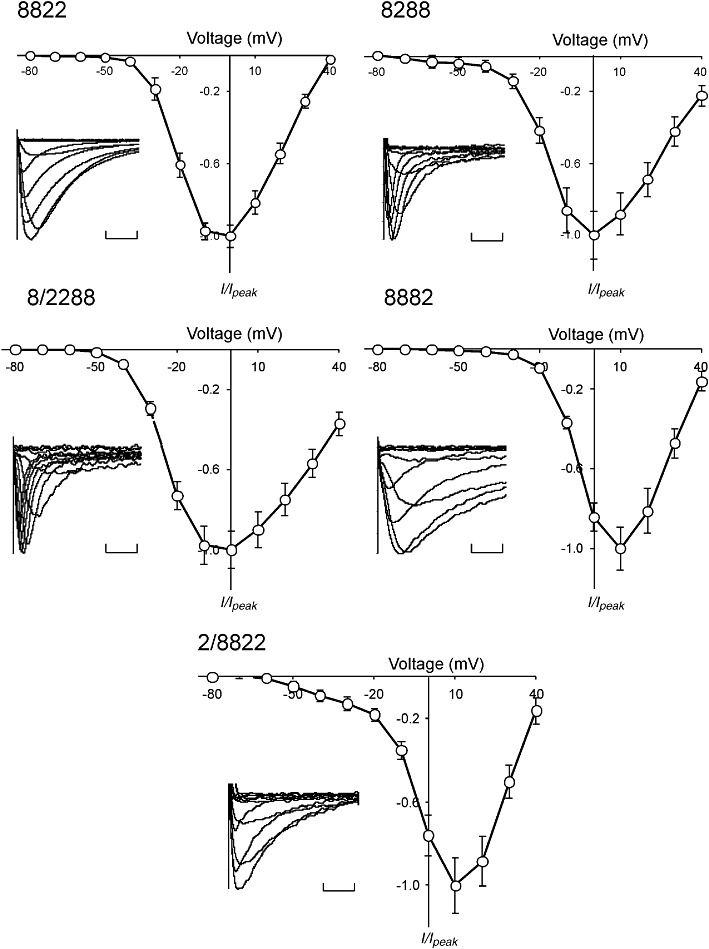

Despite similar treatment and incubation times of the oocytes, we observed large differences in peak current amplitude (Figure 2B). Chimera 8822 exhibited whole-cell Na+ currents up to 8 µA in peak amplitude, whereas currents for chimera 2288 were two orders of magnitude smaller. Figure 3 shows insets representative of whole-cell Na+ current recordings of the chimera constructs in response to depolarization voltage steps. Chimera constructs 8288 and 8/2288 exhibited fast activation and inactivation kinetics, whereas chimeras 8822, 2/8822 and 8882 produced slowly inactivating currents. The amplitude of currents recorded for chimera 2288 was insufficient for detailed analysis and was not considered further. The I–V relationships are presented in Figure 3. The peak Na+ current for chimeras 8882 and 2/8822 were positive and similar to Nav1.8. Peak current for chimeras 8288 and 8/2288 was between the peak current of Nav1.2 and Nav1.8. The I–V curve of chimera 2/8822 suggests that this particular chimera activates at a low voltage, since small currents were observed from −50 to −40 mV.

Figure 3.

Current–voltage relationships of Nav1.2/Nav1.8 chimeras expressed in oocytes. Oocytes were depolarized from a holding potential of −80 mV to voltages ranging from −80 to +40 mV in 10 mV increments. Normalized peak currents (I/Imax) of each oocyte were plotted as a function of membrane potential. Data represent mean ± SEM obtained for 8882 (n= 20), 8288 (n= 13), 2/8822 (n= 32), 8/2288 (n= 14) and 8822 (n= 16). Insets: normalized families of depolarization-activated Na+ currents for each chimera. Calibration bars = 10 ms.

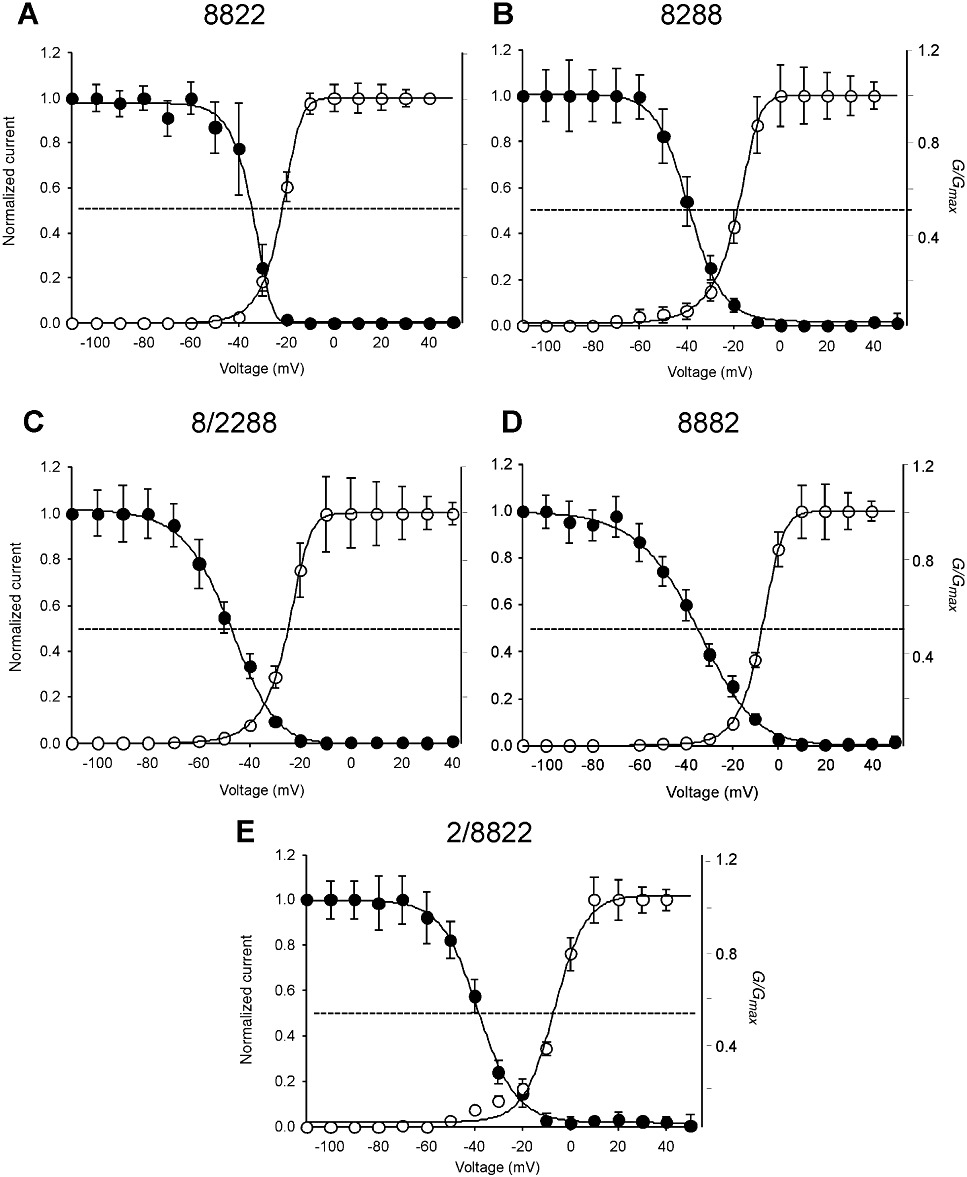

The steady-state voltage-dependence of activation of the chimeras was determined by applying a series of depolarizing voltage steps between −80 and +40 mV in 10 mV increments (Figure 4, Table 1). V1/2act for chimera 2/8822 and 8882 was similar to the parent Nav1.8 isoform, whereas 8288 had a more negative dependence of activation. Chimeras 8822 and 8/2288 were activated at voltages roughly intermediate to Nav1.2 and Nav1.8. Fast inactivation was mediated by the highly conserved intracellular loop that connects domain III and IV on the cytoplasmic side of the channel (Rogers et al., 1996; Sheets et al., 1999). The V1/2inact of chimeras 8288 and 8822 inactivated at potentials that closely resembled that of the parent Nav1.8 isomer (Figure 4, Table 1), whereas the V1/2inact for 2/8822 and 8882 occurred at a slightly more depolarized voltage. The V1/2inact of 8/2288 inactivated at a voltage that was intermediate of the parent channels.

Figure 4.

Voltage-dependence of activation and inactivation of Nav1.2/Nav1.8 chimeras. Conductance-voltage relationships (G-V) for activation and steady-state inactivation of the Na+ conductance were obtained for chimeras 8822 (A), 8288 (B), 8/288 (C), 8882 (D) and 2/8822 (E). Voltage-dependence of activation was determined by applying depolarizing pulses from a holding potential of −80 mV to +40 mV in 10 mV increments. Steady-state inactivation was determined using a two-pulse protocol where oocytes were depolarized with a test pulse to +10 mV from conditioning pre-pulse potentials (550 ms) ranging from −110 mV to +50 mV. Activation and inactivation curves were fitted with a single Boltzmann function (see methods). Data represent mean ± SEM for 8822 (n≥ 15), 8288 (n≥ 11), 8/2288 (n≥ 10), 8882 (n≥ 16) and 2/8822 (n≥ 16) (see Table 1).

The kinetic properties of the chimeras demonstrated that τact for chimera 8/2288 (0.8 ± 0.01 ms, n= 12) was akin to Nav1.2 (0.7 ± 0.04 ms, n= 12). Similarly, τact values for chimeras 8822 (1.2 ± 0.1 ms, n= 16), 8288 (1.0 ± 0.3 ms, n= 10) and 2/8822 (1.2 ± 0.1 ms, n= 18) were comparable with Nav1.8 (1.4 ± 0.04 ms, n= 19). In contrast, the τact for 8882 (2.8 ± 0.04 ms, n= 19) was dramatically slower than either parent channel. Again, the kinetics of inactivation could not be assigned to one domain. The τinact of chimera 8822 (6.7 ± 0.2 ms, n= 16) was virtually identical to parent channel Nav1.8 (6.6 ± 0.1 ms, n= 15), whereas the τinact for 8/2288 (3.4 ± 0.2 ms, n= 11) was similar to that of Nav1.2 (2.5 ± 0.1 ms, n= 7). The τinact values for 2/8822 (15.3 ± 0.2 ms, n= 10) and 8882 (14.1 ± 0.2 ms, n= 5) were significantly slower than either of the parent channels.

Effects of TTX and MrVIB on Nav1.2/Nav1.8 chimeras

As previously mentioned, the two parent channels respond differently to TTX. TTX binds to the extracellular face of the channel at the four neurotoxin receptor sites 1 and directly inhibits Na+ conductance (Noda et al., 1989; Terlau and Olivera, 2004). While Nav1.8 was partially inhibited by 100 µM TTX (Figure 5A), the current mediated by Nav1.2 was completely inhibited by 1 µM TTX (Figure 5A). All chimera constructs exhibited a reduction in response to 100 µM TTX – similar to that of Nav1.8. However, given that the concentration tested was approximately the half-maximal inhibitory concentration for block of TTX-R VGSCs (Akopian et al., 1996; Sivilotti et al., 1997), further experiments are needed to quantify the TTX sensitivity of Nav1.2/Nav1.8 chimeras.

Previous studies have shown that the µO-conotoxin MrVIB selectively inhibits Nav1.8 expressed in Xenopus oocytes with ∼10-fold lower potency than other VGSCs, such as Nav1.2 (Ekberg et al., 2006b). We used this difference in toxin affinity to determine which transmembrane domain of Nav1.8 is involved in MrVIB binding by comparing the MrVIB binding capabilities of Nav1.2, Nav1.8 and their chimeras. Figure 5A shows the average inhibition of Na+ peak current after the application of 1 µM MrVIB for each channel construct. Bath application of 1 µM MrVIB caused a small reduction in Nav1.2 current amplitude, with Na+ current reduced to 67 ± 12% (n= 7) when compared with control. As described previously, Nav1.8 had a high binding affinity for MrVIB, but in contrast with previous studies, 1 µM MrVIB was not sufficient to completely inhibit (Ekberg et al., 2006b). Instead, 31 ± 3% (n= 8) of the current amplitude remained. A similar effect was seen when MrVIB was applied to chimeras 8822 (21 ± 4%, n= 6), 2/8822 (40 ± 5%, n= 11) and 8882 (41 ± 4%, n= 11). These effects suggest that the region extending from S6 segment of domain I through the S5-S6 linker of domain II of Nav1.8 is a major determinant of MrVIB binding affinity, as chimeras that retained this domain had similar toxin inhibitory effects to those of the parent Nav1.8 isoform. Moreover, MrVIB did not change the I–V relationship for chimeras that contained domain II from the Nav1.8 parent channel (Figure 5B). In contrast to findings reported by Zorn et al. (2006), MrVIB application had only a small effect on chimeras 8288 and 8/2288 that contained domain III from Nav1.8, with the remaining current 81 ± 6% (n= 5) and 82 ± 8% (n= 6), respectively. Therefore, it appears that domain III is less important for MrVIB binding than the region extending from S6 of domain I through the S5–S6 linker of domain II of Nav1.8.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we report on the generation and expression of chimeras between two VGSC α-subunit isoforms, human Nav1.8 and rat Nav1.2, and their ability to bind the µO-conotoxin MrVIB. The key finding was that chimeras with the region extending from S6 segment of domain I through the S5–S6 linker of domain II were needed to establish the Nav1.8 phenotype of MrVIB inhibition.

When expressed in Xenopus oocytes, Nav1.2 mediated robust TTX-S fast activating and inactivating inward voltage-dependent Na+ currents in response to depolarizing voltage steps. In contrast, Nav1.8 mediated a TTX-R Na+ current with slow kinetics characteristic of Nav1.8 in native DRG neurons (Akopian et al., 1996; Djouhri et al., 2003). A 30 mV difference in the voltage-dependence of activation was apparent between Nav1.2 and Nav1.8, whereas inactivation curves differed by 20 mV. Overall Nav1.2- and Nav1.8-mediated currents were similar to those reported previously for Nav1.2 and Nav1.8 expressed in Xenopus oocytes, in terms of kinetic and gating properties (Shah et al., 2000; Vijayaragavan et al., 2001).

Large differences in peak current amplitude of the Nav chimeras were observed, despite oocytes having similar treatment and incubation times. Chimera 8822 produced whole-cell Na+ currents up to 8 µA in amplitude, whereas currents obtained for chimera 2288 were ∼100 nA, nearly two orders of magnitude smaller. Reduced Na+ current amplitude may be attributed to a lower expression level. Expression of Nav1.8 is known to be controlled by auxiliary β subunits (Isom, 2001; Vijayaragavan et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2008); therefore, co-expression of 2288 with a β subunit might result in a larger peak current. Apart from the β3 subunit interaction, these differences in current amplitude of the chimeras may also be caused by the involvement of regulatory mechanisms, including modulation of channel opening probability, stabilization of the channel in the plasma membrane, alterations in trafficking or signalling events leading to increased mRNA levels. In addition, Nav1.8 can interact with a number of intracellular proteins, including cytoskeletal proteins, channel-associated proteins, motor proteins and enzymes, which may also regulate Nav1.8 membrane density (Malik-Hall et al., 2003; Vijayaragavan et al., 2004).

Despite the often relatively large differences in chimera channel properties, it is not straightforward to assign mechanisms to distinct domains of VGSCs because of overlapping functions across the six transmembrane-spanning helices within the four domains. For example, each domain contains structurally and functionally related voltage-gating S4 segments and pore-forming segments (Catterall et al., 1986; Guy and Seetharamulu, 1986). In contrast, fast inactivation is mediated by the highly conserved intracellular loop that connects domains III and IV on the cytoplasmic side of the channel (Rogers et al., 1996; Sheets et al., 1999). An exchange of this loop in Nav1.8 for the corresponding loop in Nav1.2 did not result in channels with the kinetics of Nav1.2 (Figure 4, Table 1). Instead, τinact was much slower than that of the two parent channels, confirming that other parts of the VGSC contribute to fast inactivation and suggesting there may be isoform-specific complementarity of the structural components of inactivation. Nevertheless, an intrusion in this structural composition causes biophysical changes (Figure 4, Table 1).

TTX binds to the extracellular face of the channel at the neurotoxin receptor site 1 and directly inhibits Na+ conductance. Site 1 is located in the N-terminal portion of S6 transmembrane helix in all four domains of the VGSC α-subunit (Noda et al., 1989; Terlau et al., 1991). TTX sensitivity is largely determined by a single residue in site 1 in the VGSC α-subunit. In TTX-S VGSCs, a phenylalanine (Nav1.1 and Nav1.2) or tyrosine (Nav1.3, Nav1.4, Nav1.6 and Nav1.7) residue is located at this position, whereas in TTX-R VGSCs (Nav1.8 and Nav1.9), this residue is replaced by a serine (Sivilotti et al., 1997). In Nav1.5, a channel with intermediate TTX sensitivity, a cysteine is present (Backx et al., 1992; Heinemann et al., 1992; Satin et al., 1992). These findings suggest that hydrophobic interactions between TTX and aromatic residues at this position are important for TTX binding, with mutations to hydrophilic or charged residues reducing TTX affinity at Nav1.2. Alternatively, Santarelli et al. (2007) provided evidence that the aromatic residue is involved in a cation–π electron interaction, rather than a hydrophobic one. Since all chimeras had reduced TTX affinity, it appears that introducing the S6 segment from only one or two domains of Nav1.2 is insufficient to restore high-affinity TTX binding. However, the high TTX concentration (100 µM) in our study would not distinguish between the TTX sensitivity of the chimeras. Given that TTX concentration–response relationships were not carried out, chimeras with an intermediate TTX sensitivity (in relation to Nav1.2 and Nav1.8) were undetected.

There is considerable interest in elucidating the binding mechanism of the µO-conotoxins MrVIA and MrVIB, since they were identified as modestly selective inhibitors of TTX-R voltage-gated Na+ currents in rat DRG neurons (Daly et al., 2004) and effectively inhibited pain behaviours in neuropathic pain (Bulaj et al., 2006; Ekberg et al., 2006b). An inhibitory effect of MrVIA on the muscle-type VGSC Nav1.4 was described previously (Leipold et al., 2007). These studies revealed that the voltage sensor of domain II had the strongest effect on MrVIA action (Leipold et al., 2007), whereas competition experiments with the scorpion toxin β-toxin Ts1 and MrVIA on Nav1.4 indicated µO-conotoxin binding depended on the pore loop in domain III (Zorn et al., 2006). Interestingly, Wilson et al. (2011) showed that β1, β2, β3 and β4 subunits, when individually co-expressed with Nav1.8 in Xenopus oocytes, increased the kon of the block produced by µO-MrVIB and modestly decreased the apparent koff. However, neither of the above studies examined the binding site and mechanism of action of µO-conotoxins on Nav1.8. The amino acid sequence of Nav1.8 is only about 50% identical to Nav1.2 at the amino acid level and 65% homologous. Therefore, ∼880 amino acids differ between Nav1.8 and other VGSCs. To address the functional and pharmacological significance of these differences, a domain-swapping strategy between two VGSC with different binding affinity for MrVIB can be used to determine which domain makes the greatest contribution to toxin binding. The same is true for Nav1.9, which has the most divergent amino acid sequence among all Nav channel isoforms (Catterall et al., 2005). To study the interaction of Nav1.9 voltage sensors with scorpion and tarantula toxins, the voltage sensor paddle motifs were transferred into the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv2.1 (Bosmans et al., 2011).

Recently, an approach using domain chimeras between Nav1.4 and Nav1.5 identified the binding site of the pore-blocking µ-conotoxin SIIIA within the first half of the channel protein, with a major contribution of domain II and a minor contribution of domain I (Leipold et al., 2011). We exploited the higher potency of MrVIB for Nav1.8 compared with Nav1.2 (Ekberg et al., 2006b), and demonstrated that the region in Nav1.8 extending from S6 of domain I through the S5-S6 linker of domain II was the major determinant of its high-affinity binding. MrVIB inhibition of Nav1.8 is probably mediated via an interaction with the voltage sensor of domain II. However, the possibility that MrVIB interacts with other channel domains cannot be excluded. Voltage-sensor toxins, such as those from tarantulas, can interact simultaneously with multiple channel domains and their voltage sensors within one Nav channel (Bosmans et al., 2008; Bosmans and Swartz, 2010). For example, the tarantula toxin HWTX-IV is a voltage sensor modifier that interacts with the domain II voltage sensor. The critical domain II residues for HWTX-IV interaction also regulate the ability of the domain IV voltage sensor to interact with HWTX-IV (Xiao et al., 2008; 2011). ProTx-II, another tarantula toxin, can inhibit Nav1.7 activation by interacting with domain II and impair Nav1.7 inactivation by interacting with domain IV (Xiao et al., 2010). However, mutating equivalent residues in Nav1.2 did not significantly influence sensitivity to ProTx-II, suggesting other interaction sites in different regions of the channel. A significant advance in identification of binding sites within the VGSC voltage sensors was achieved by identifying S3b-S4 paddle motifs within the four Nav channel voltage sensors and transplanting them into the fourfold symmetric Kv channels. This enabled the examination of their individual interactions with toxins from tarantulas and scorpions (Bosmans et al., 2008). This study demonstrated that each of the paddle motifs can interact with tarantula or scorpion toxins, and that multiple paddle motifs are often targeted by a single toxin. Leipold et al. identified the voltage sensor in domain II as the main binding site for µO-conotoxins in Nav1.4, whereas interactions with domain III appeared to play a lesser role (Leipold et al., 2007; cf.Zorn et al., 2006). In the present study, our complementary results revealed MrVIB also binds to domain II in Nav1.8. Comprehensive point mutational studies are now needed to identify the specific binding site residues in domain II that interact with MrVIB in this region.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program Grant (569927). DJA is an Australian Research Council Australian Professorial Fellow, and RJL is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow.

Glossary

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- RE

restriction enzyme

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- TTX-R

tetrodotoxin-resistant

- TTX-S

tetrodotoxin-sensitive

- VGSC

voltage-gated sodium channel

Conflicts of interest

The authors state no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akopian AN, Sivilotti L, Wood JN. A tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel expressed by sensory neurons. Nature. 1996;379:257–262. doi: 10.1038/379257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian AN, Souslova V, England S, Okuse K, Ogata N, Ure J, et al. The tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel SNS has a specialized function in pain pathways. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:541–548. doi: 10.1038/9195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backx PH, Yue DT, Lawrence JH, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Molecular localization of an ion-binding site within the pore of mammalian sodium channels. Science. 1992;257:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1321496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans F, Swartz KJ. Targeting voltage sensors in sodium channels with spider toxins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans F, Martin-Eauclaire MF, Swartz KJ. Deconstructing voltage sensor function and pharmacology in sodium channels. Nature. 2008;456:202–208. doi: 10.1038/nature07473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans F, Puopolo M, Martin-Eauclaire MF, Bean BP, Swartz KJ. Functional properties and toxin pharmacology of a dorsal root ganglion sodium channel viewed through its voltage sensors. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138:59–72. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulaj G, Zhang MM, Green BR, Fiedler B, Layer RT, Wei S, et al. Synthetic µO-conotoxin MrVIB blocks TTX-resistant sodium channel Nav1.8 and has a long-lasting analgesic activity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7404–7414. doi: 10.1021/bi060159+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Schmidt JW, Messner DJ, Feller DJ. Structure and biosynthesis of neuronal sodium channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;479:186–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb15570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:397–409. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly NL, Ekberg J, Thomas L, Adams DJ, Lewis RJ, Craik DJ. Structures of µO-conotoxins from Conus marmoreus. Inhibitors of tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive and TTX-resistant sodium channels in mammalian sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25774–25782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouhri L, Fang X, Okuse K, Wood JN, Berry CM, Lawson SN. The TTX-resistant sodium channel Nav1.8 (SNS/PN3): expression and correlation with membrane properties in rat nociceptive primary afferent neurons. J Physiol. 2003;550:739–752. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg J, Adams DJ. Neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel subtypes: key roles in inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006a;38:2005–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg J, Jayamanne A, Vaughan CW, Aslan S, Thomas L, Mould J, et al. µO-conotoxin MrVIB selectively blocks Nav1.8 sensory neuron specific sodium channels and chronic pain behavior without motor deficits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006b;103:17030–17035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601819103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmi AI, Patel M, Stevens EB, Fowden AL, John JE, Lee K, et al. The sodium channel β-subunit SCN3b modulates the kinetics of SCN5a and is expressed heterogeneously in sheep heart. J Physiol. 2001;537:693–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fainzilber M, van der Schors R, Lodder JC, Li KW, Geraerts WP, Kits KS. New sodium channel-blocking conotoxins also affect calcium currents in Lymnaea neurons. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5364–5371. doi: 10.1021/bi00016a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin A. Resurgence of sodium channel research. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:871–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourfinkel-An I, Baulac S, Nabbout R, Ruberg M, Baulac M, Brice A, et al. Monogenic idiopathic epilepsies. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:209–218. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00706-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy HR, Seetharamulu P. Molecular model of the action potential sodium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:508–512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne RP, Catterall WA. The sodium channel from rat brain. Purification and subunit composition. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:1667–1675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne RP, Messner DJ, Coppersmith JC, Catterall WA. The saxitoxin receptor of the sodium channel from rat brain. Evidence for two non-identical β subunits. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13888–13891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann SH, Terlau H, Imoto K. Molecular basis for pharmacological differences between brain and cardiac sodium channels. Pflügers Arch. 1992;422:90–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00381519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B, Armstrong CM, MacKinnon R. Ion channels: from idea to reality. Nat Med. 1999;5:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/13415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom L. Sodium channel β subunits: anything but auxiliary. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:42–54. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkat-Rott K, Lehmann-Horn F. Muscle channelopathies and critical points in functional and genetic studies. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2000–2009. doi: 10.1172/JCI25525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipold E, Hansel A, Olivera BM, Terlau H, Heinemann SH. Molecular interaction of δ-conotoxins with voltage-gated sodium channels. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3881–3884. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipold E, DeBie H, Zorn S, Borges A, Olivera BM, Terlau H, et al. µO-conotoxins inhibit Nav channels by interfering with their voltage sensors in domain-2. Channels. 2007;1:253–262. doi: 10.4161/chan.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipold E, Markgraf R, Miloslavina A, Kijas M, Schirmeyer J, Imhof D, et al. Molecular determinants for the subtype specificity of µ-conotoxin SIIIA targeting neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li RA, Tomaselli GF. Using the deadly µ-conotoxins as probes of voltage-gated sodium channels. Toxicon. 2004;44:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li RA, Hui K, French RJ, Sato K, Henrikson CA, Tomaselli GF, et al. Dependence of µ-conotoxin block of sodium channels on ionic strength but not on the permeating [Na+]: implications for the distinctive mechanistic interactions between Na+ and K+ channel pore-blocking toxins and their molecular targets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30912–30919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik-Hall M, Poon WY, Baker MD, Wood JN, Okuse K. Sensory neuron proteins interact with the intracellular domains of sodium channel Nav1.8. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;110:298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00661-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JM, Hasson A, Spira ME, Gray WR, Li W, Marsh M, et al. A new family of conotoxins that blocks voltage-gated sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16796–16802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra SN, Kahlig KM, George AL. Impaired Nav1.2 function and reduced cell surface expression in benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1535–1545. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan K, Stevens EB, Shah B, Cox PJ, Dixon AK, Lee K, et al. β3: an additional auxiliary subunit of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel that modulates channel gating with distinct kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2308–2313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030362197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulley JC, Scheffer IE, Petrou S, Berkovic SF. Channelopathies as a genetic cause of epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:171–176. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000063767.15877.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HM, Goldin AL. Sodium channel carboxyl-terminal residue regulates fast inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9077–9089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M, Shimizu S, Tanabe T, Takai T, Kayano T, Ikeda T, et al. Primary structure of Electrophorus electricus sodium channel deduced from cDNA sequence. Nature. 1984;312:121–127. doi: 10.1038/312121a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M, Suzuki H, Numa S, Stühmer W. A single point mutation confers tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin insensitivity on the sodium channel II. FEBS Lett. 1989;259:213–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JC, Qu Y, Tanada TN, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of high affinity binding of α-scorpion toxin and sea anemone toxin in the S3-S4 extracellular loop in domain IV of the Na+ channel α subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15950–15962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.15950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangameswaran L, Fish LM, Koch BD, Rabert DK, Delgado SG, Ilnicka M, et al. A novel tetrodotoxin-sensitive, voltage-gated sodium channel expressed in rat and human dorsal root ganglia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14805–14809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli VP, Eastwood AL, Dougherty DA, Horn R, Ahern CA. A cation-π interaction discriminates among sodium channels that are either sensitive or resistant to tetrodotoxin block. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8044–8051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satin J, Kyle JW, Chen M, Bell P, Cribbs LL, Fozzard HA, et al. A mutant of TTX-resistant cardiac sodium channels with TTX-sensitive properties. Science. 1992;256:1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BS, Stevens EB, Gonzalez MI, Bramwell S, Pinnock RD, Lee K, et al. β3, a novel auxiliary subunit for the voltage-gated sodium channel, is expressed preferentially in sensory neurons and is up regulated in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3985–3990. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets MF, Kyle JW, Kallen RG, Hanck DA. The Na channel voltage sensor associated with inactivation is localized to the external charged residues of domain IV, S4. Biophys J. 1999;77:747–757. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76929-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivilotti L, Okuse K, Akopian AN, Moss S, Wood JN. A single serine residue confers tetrodotoxin insensitivity on the rat sensory-neuron-specific sodium channel SNS. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MR, Smith RD, Plummer NW, Meisler MH, Goldin AL. Functional analysis of the mouse SCN8a sodium channel. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6093–6102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06093.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Goldin AL. Functional analysis of the rat I sodium channel in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurosci. 1998;18:811–820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-00811.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlau H, Olivera BM. Conus venoms: a rich source of novel ion channel-targeted peptides. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:41–68. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlau H, Heinemann SH, Stühmer W, Pusch M, Conti F, Imoto K, et al. Mapping the site of block by tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin of sodium channel II. FEBS Lett. 1991;293:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaragavan K, O'Leary ME, Chahine M. Gating properties of Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 peripheral nerve sodium channels. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7909–7918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07909.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaragavan K, Boutjdir M, Chahine M. Modulation of Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 peripheral nerve sodium channels by protein kinase A and protein kinase C. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1556–1569. doi: 10.1152/jn.00676.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj S, Cummins TR, Black JA. Sodium channels and pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7635–7639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MJ, Zhang MM, Azam L, Olivera BM, Bulaj G, Yoshikami D. Navβ subunits modulate the inhibition of Nav1.8 by the analgesic gating modifier µO-conotoxin MrVIB. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:687–693. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.178343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JN, Abrahamsen B, Baker MD, Boorman JD, Donier E, Drew LJ, et al. Ion channel activities implicated in pathological pain. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;261:32–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Bingham JP, Zhu W, Moczydlowski E, Liang S, Cummins TR. Tarantula huwentoxin-IV inhibits neuronal sodium channels by binding to receptor site 4 and trapping the domain II voltage sensor in the closed configuration. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27300–27313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708447200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Blumenthal K, Jackson JO, Liang S, Cummins TR. The tarantula toxins ProTx-II and huwentoxin-IV differentially interact with human Nav1.7 voltage sensors to inhibit channel activation and inactivation. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:1124–1134. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.066332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Jackson JO, Liang S, Cummins TR. Common molecular determinants of tarantula huwentoxin-IV inhibition of Na+ channel voltage sensors in domains II and IV. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27301–27310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.246876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Catterall WA. Overview of the voltage-gated sodium channel family. Genome Biol. 2003;4:207.1–207.7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-3-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Westenbroek RE, Silos-Santiago I, McCormick KA, Lawson D, Ge P, et al. Sodium channel β4, a new disulfide-linked auxiliary subunit with similarity to β2. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7577–7585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZN, Li Q, Liu C, Wang HB, Wang Q, Bao L. The voltage-gated Na+ channel Nav1.8 contains an ER-retention/retrieval signal antagonized by the β3 subunit. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3243–3252. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorn S, Leipold E, Hansel A, Bulaj G, Olivera BM, Terlau H, et al. The µO-conotoxin MrVIA inhibits voltage-gated sodium channels by associating with domain-3. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1360–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]