Abstract

Insufficient cell number hampers therapies utilizing adult human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) and current ex vivo expansion strategies lead to a loss of multipotentiality. Here we show that supplementation with an embryonic form of heparan sulfate (HS-2) can both increase the initial recovery of hMSCs from bone marrow aspirates and increase their ex vivo expansion by up to 13-fold. HS-2 acts to amplify a subpopulation of hMSCs harboring longer telomeres and increased expression of the MSC surface marker stromal precursor antigen-1. Gene expression profiling revealed that hMSCs cultured in HS-2 possess a distinct signature that reflects their enhanced multipotentiality and improved bone-forming ability when transplanted into critical-sized bone defects. Thus, HS-2 offers a novel means for decreasing the expansion time necessary for obtaining therapeutic numbers of multipotent hMSCs without the addition of exogenous growth factors that compromise stem cell fate.

Introduction

The capacity of adult human stem cells to undergo both self-renewal and directed differentiation is essential for the development of cell-based therapies, with bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) representing one of the few stem cell types currently undergoing phase III clinical trials [1,2]. Tissue regeneration has been reported after delivery of adult stem cells, either locally for cardiovascular regeneration [3] or systemically [4–6]. One significant advantage is that these cells have potent immunosuppressive effects in vivo, [7,8] making them useful for co-transplantation. However, widespread use of hMSCs is hindered by their low abundance [3]. The majority of in vitro and in vivo studies have utilized cells from bone marrow isolated by plastic adherence [9]. The limitation of this technique is that it yields low frequencies of clonogenic colony forming units-fibroblastic (CFU-F) together with significant numbers of contaminating cells [10]. Further, the number of isolated stem cells is greatly influenced by the volume and technique of marrow aspiration. To a large extent these drawbacks can be mitigated by enrichment of the starting populations by immunoselection for markers such as stromal precursor antigen-1 (STRO-1) [11,12] or stage-specific embryonic antigen-4 (SSEA-4) [13].

To obtain sufficient numbers for use in therapy, hMSCs require further ex vivo expansion. Indeed, most clinical trials require between 0.5×106 and 5×106/kg mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [14]. Much work has been conducted to improve the rates of ex vivo expansion, particularly the addition of soluble peptide mitogens, [15–17] including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-containing platelet lysates [18]. However, such protocols have been shown to result in a loss of multipotentiality [19]. Also, extended time in culture may result in altered cell cycle progression, major genomic alterations (polyploidy and aneuploidy), and the inability to become senescent or quiescent [20].

The maintenance of multipotentiality is known to require a delicate balance of opposing extracellular factors. One mitogen shown to be a powerful mediator of proliferation for both embryonic and adult stem cells is fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) [21]. FGF-2 has been shown to sustain both the proliferative, and subsequent osteogenic potential of stem cells derived from mouse adipose tissue by suppressing the retinoic acid-mediated upregulation of BMPR1B [22]. Thus the balance of FGFs and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) is central to the proliferation of naïve stem cells, the timing of their commitment, and their eventual differentiation down the osteogenic lineage.

Several other strategies have been explored for the ex vivo expansion of hMSCs, including the forced expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) (telomerase catalytic sub-unit), [23,24] and exposure to extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules [25]. When transduced with hTERT, hMSCs failed to senesce, and could be cultured for more than 260 population doublings, but became tumorigenic [26]. Key elements of the ECM are also known to support progenitor cell self-renewal; one of the most active is the family of heparan sulfate (HS) glycosaminoglycan (GAG) sugars, [27] with the actions of many growth and adhesive factors dependent on specific forms of this carbohydrate [28].

We have previously described an embryonic HS preparation that binds FGF-2 (HS-2) [29] with potent bioactivity for neural precursor cells. As FGF-2 is a potent mitogen for stem cells, including hMSCs, we examined the biological activity of HS-2 as a culture supplement. HS-2 induces the proliferative expansion of a naïve hMSC subpopulation contained within a heterogeneous pool of adherent bone marrow cells, without adversely affecting their multipotentiality. Cultures supplemented with HS-2 yield therapeutic numbers of cells that augment bone formation when transplanted in vivo. These findings are consistent with the concept that selected GAGs can be developed to promote specific biological outcomes for stem cells in regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Human MSC isolation and cell culture

Human MSCs (PT-2501; Lonza) were maintained in dulbecco's modified eagle's medium, 1,000 mg/l glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Media was changed at 3-day intervals and the cells subcultured every 4–5 days (∼80% confluency); aliquots from passages 2–5 were frozen in liquid nitrogen for future use. Unprocessed human bone marrow withdrawn from bilateral punctures of the posterior iliac crest of the pelvic bone of 3 normal volunteers aged 18–45 years (1M-125; Lonza) was separately subjected to Ficoll gradient separation to isolate hMSCs and to eliminate unwanted cell types. Cells were then plated and cultured as previously reported [30].

Characterization of hMSC immunophenotype

Flow cytometric analysis was conducted to compare the profiles of HS-2-expanded and control–expanded hMSCs for CD49a, CD73 (BD Bioscience), CD105 (eBioscience), and STRO-1 (R&D Systems), or isotype-matched controls as previously reported [30, 37]. Samples were analyzed using a Guava principal component analysis (PCA-96) bench top flow cytometer and Guava Express Software (Millipore).

Colony-forming units-fibroblastic

Colony efficiency was assayed in the presence or absence of the HS-2 supplement. Bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs; 3×105/cm2) or hMSCs (30 cells/cm2) were plated in triplicate, in 24-well plates and cultured for 14 days as previously described [30]. Colonies with more than 50 cells that were not in contact with other colonies were counted.

Proliferation and apoptotic assays

Cell number, cell cycle kinetics (propidium iodide), and apoptosis (Annexin V) were analyzed on a GUAVA PCA-96 benchtop flow cytometer following the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore). Proliferation-related metabolic activity was determined by incubation of cells with 4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,3-benzene disulfonate (WST-1) as per the manufacturer's recommendations (Roche). Human MSCs (3.3×103) were plated in 96-well plates in HS-2-supplemented or control media and cultured for varying time points. For BrdU assays, cells (2.1×105 cells/cm2) were allowed to adhere (2 h) in 96-well plates, then serum-starved (0.2% FBS) overnight, before the addition of media with or without HS-2. BrdU incorporation was measured using the Cell Proliferation ELISA kit (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions. To determine the effect of HS-2 supplementation on cumulative cell number (long-term growth), hMSCs were plated at 5×103 cells per cm2 and cultured to 80% confluency, lifted with tryspin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), counted (Guava Express Software), and then replated at 5×103 cells per cm2. This process was repeated for 45 days with media changes twice weekly.

Telomere length

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from cells expanded in the presence or absence of HS-2 at various time points. Cells were washed in PBS and lysed in buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaCl, 1% SDS 0.05 mg/mL, and RNase A -DNase free) at 37°C overnight. Proteinase K (1 mg/mL) was then added to the lysates that were further incubated for 5 h at 37°C. DNA was precipitated with 2 volumes of absolute ethanol and 250 mM NaCl. Precipitates were washed in 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in H2O. DNA was quantified and 12.5 ng used for amplification of both the 36B4 gene and telomeric repeats by real-time quantitative (RQ)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in triplicate, as previously reported [31,32]. The relative expression of telomeric repeats and 36B4 was estimated from standard curves (Ct vs. log quantity) made from chromosomal DNA isolated from the BG01V human embryonic stem cell line (Invitrogen).

Stem cell microarray

Total RNA was purified from control and HS-2 cultures after the nominated days in culture. Triplicate-labeled RNA samples were pooled (1:1:1) and used as probes on chemiluminescent cDNA arrays (GEArray S Series Human Stem Cell Gene Array, SuperArray Bioscience Corporation). This procedure was repeated 3 times for each group for a total of 3 triplicate pooled samples per group. Arrays were analyzed using a Chemi-Smart 3000 image acquisition system (Vilber Lourmat). To more fully describe the time-course effect of HS-2 on hMSC gene expression measurements, we reconstructed the genetic network based on analyses of our microarray experiments using singular value decomposition (SVD) and PCA [33]. PCA has previously been shown to be sensitive enough to distinguish between tumor subtypes using their gene expression signature [34] and exoprotease activity [35]. Fold changes in gene expression were calculated and the data hierarchically clustered by function with DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.7 (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) [36] and a graphical heat map generated (http://api.imapbuilder.net/editor/).

Immunomodulation

Human MSCs expanded for 21 days in control or HS-2-containing media were seeded at 1×105 cells/well in 96-well plates. A mixture of stimulatory and reactionary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from two different healthy un-matched donors (Singapore Cord Blood Bank) was added to the wells 24 h later at different hMSC:PBMC ratios and the cells incubated for 6 days before the expression of CD3+ Ki67+ cells was assessed by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) as previously reported [37].

Multilineage differentiation

Human MSCs were serially passaged in HS-2 or control media then detached in trypsin/EDTA, and reseeded to compare their ability to either deposit a bone-like matrix, form lipid droplets, or secrete GAGs when stimulated with osteogenic, adipogenic, or chondrogenic supplements (in the absence of HS-2) as previously described [30]. In parallel cultures, total RNA was isolated and the levels of mRNA transcripts for osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic biomarkers determined as previously described [30,37]. Clonal assays were also performed on hMSCs expanded in HS-2 or control media for 13 population doublings. Single cells were seeded into 96-well plates using a FACSAria (BD Bioscience) and cultured for 14 days in the presence or absence of HS-2, and the colony-forming efficiency assessed as described above. From parallel wells, cloned hMSCs were serially passaged in the presence or absence of HS-2 and their multilineage potential reassessed as above.

In vivo bone formation

Composite scaffolds containing hMSCs

HS-2- or control-expanded hMSCs (1×106 cells; passage 4) were loaded onto Poly (ɛ-caprolactone)-tricalcium phosphate (PCL-TCP) composite scaffolds [37] (Osteopore International) and placed into 24-well culture plates, mixed with Fibrin Tisseel Sealant (Tisseel kit, Immuno) in a 3:1 ratio as previously described [37]. After cell seeding, 1 mL of fresh culture medium was added to each well and cells were incubated in humidified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2 overnight before transplantation.

Rat femoral defect model

To determine the efficacy of HS-2-expanded hMSCs for bone healing, composite scaffolds containing hMSCs were transplanted into bilateral segmental critical-sized femoral defects in nude rats. The research protocol for the use of 18 male, CBH/Rnu rats, weighing 230–260 g was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Agency for Science Technology and Research, Singapore following all appropriate guidelines. All surgical procedures were performed as previously established [37]. Briefly, after exposing the femur via a longitudinal incision over the proximal hind limb, femurs were stabilized with custom modular fixation plates and 8 mm bilateral segmental critical-sized defects were created with a miniature oscillating saw. Each rat received an hMSC-seeded PCL-TCP scaffold (control group) in one of the femoral defects, with the contralateral femoral defect receiving an HS-2-expanded, hMSC-seeded, PCL-TCP scaffold (HS-2 group). After euthanasia at 3 and 7 weeks postsurgery, samples were harvested and stored in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for subsequent two-dimensional (2D) radiography (n=6 per group), 3D micro-computed tomography (μ-CT; n=6 per group), cell survival analyses (n=3 per group), histology (n=3 per group), and immunohistochemistry (n=3 per group).

Paraffin histology, cell survival, 2D radiography, and μ-CT analysis

Paraffin histology, cell survival analysis and imaging of defects were performed at weeks 3 and 7 as previously described [37].

Resin histology

Selected femurs were subjected to undecalcified resin processing/embedding in methylmethacrylate as per our previously established methods [38]. Transverse sections were cut at 5 μm and stained with MacNeal/von Kossa, and examined under an Olympus Stereo (SZX12) microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

The procedures were performed according to our previously established methods.[38] Tissue sections were incubated with either the primary antibodies for osteocalcin (Abcam), or the same concentration of mouse IgG (Caltage Laboratories) as a negative control.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) for at least 3 independent experiments, each measured in triplicate. Two-tailed unpaired t-tests were performed and significant differences between the control and HS-2 groups are marked with a single (p<0.05), double (p<0.005), or triple asterisk (p<0.0001).

Results

HS-2 increases hMSC growth and maintains their viability

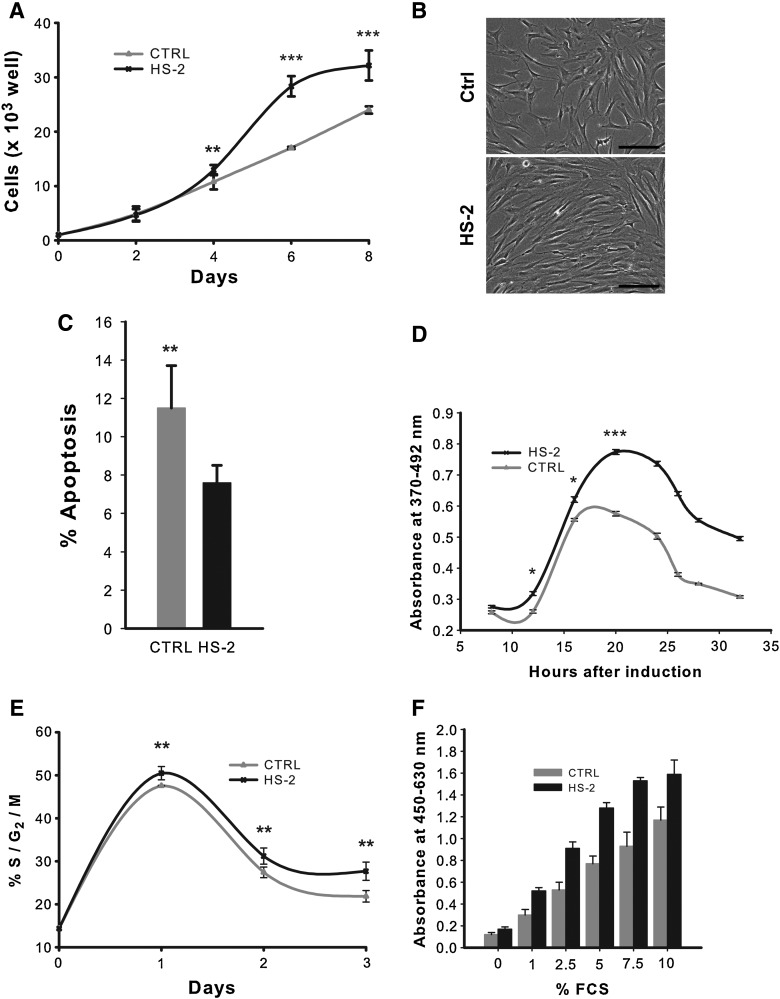

Pilot experiments revealed that the optimal dosage for HS-2 in enhancing cell proliferation is in the ng/mL range, with 160 ng/mL yielding maximal stimulatory activity (data not shown), consistent with our previous report.[39] This concentration was used for all HS-2-supplemented experiments in this study. HS-2 increased the proliferation of sub-confluent hMSCs over a 6-day period by ∼65% (p<0.0001) (Fig. 1A), consistent with microscopic observations (Fig. 1B). This increased cell number is due in part to a modest increase in cell viability (data not shown) and reduced apoptosis based on Annexin V staining (Fig. 1C). To discriminate between HS-2 effects on cell cycle kinetics as opposed to the proliferation-quiescence transition, we performed serum deprivation experiments (Fig. 1D, E). Serum-deprived quiescent cells were stimulated with serum in the absence or presence of HS-2. Serum stimulation results in S-phase entry by 15 h with or without the HS. However the number of cells in S-phase was much greater on HS-2 stimulation (Fig. 1D). Similarly, HS-2 increased the amount of G2/M cells but not their temporal appearance after serum stimulation (Fig. 1E). Thus HS-2 does not affect the temporal progression through G1 resulting in S-phase and G2 entry, but rather the number of cells that enter the cell cycle from G0 after serum stimulation.

FIG. 1.

Short-term exposure to heparan sulfate-2 increases the proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells. (A) Growth of cells exposed to 160 ng/mL heparan sulfate (HS-2) over 8 days; (B) their morphology under an inverted phase contrast microscope, bar=200 μm. (C) Apoptotic levels after 8 days exposure to HS-2. (D) Incorporation of BrdU during short-term exposure to HS-2. (E) Proportion of cells in S/G2/M phases of the cell cycle when cultured in HS-2. (F) HS-2 sustains the growth of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) in decreasing concentrations of FCS as determined by WST-1 assay. Error bars represent the standard deviation, n=3.

Because HS-2 appears to affect the G0/G1 transition, we addressed whether HS-2 could improve the proliferative effect of FCS as measured by WST-1 assays that monitor proliferation-related metabolic activity (Fig. 1F). Gradually decreasing FCS concentrations from 10% to 1% resulted in reduced proliferative activity. However in the presence of HS-2, the mitogenic activity of FCS was markedly improved; for example, activity levels at 2.5% FCS with HS-2 mirror those with 7.5% FCS without HS-2. Further, activity levels at 5% FCS or higher all exhibited more robust proliferative activity with HS-2 compared with the normal dose of 10% FCS. Interestingly, supplementation with HS-2 caused hMSCs to release significant amounts of FGF2 (data not shown), suggesting the GAG-triggered formation/enhancement of an autocrine loop. Collectively, these results indicate that HS-2 increases cell number by stimulating a population of normally quiescent cells to enter the cell cycle and sustain their proliferation.

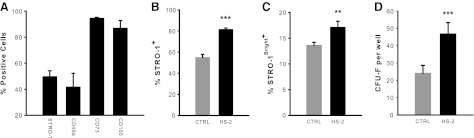

To determine whether HS-2 supplementation affects the immunophenotypic profile of hMSCs, we performed flow cytometric analyses of sub-cultured cells. We first established basal expression profiles on hMSCs and noted high expression of CD73 and CD105 and moderate expression of CD49a and STRO-1 (Fig. 2A). These cells where then further expanded in control or HS-2 supplemented media and again analyzed for STRO-1 expression (Fig. 2B, C). HS-2 treatment resulted in significantly greater STRO-1 expression, including the STRO-1Bright+ population. This finding was corroborated by colony efficiency assays, with HS-2-expanded cells forming ∼2-fold more colonies compared with cells cultured in control media (Fig. 2D). Collectively these data suggest that HS-2 has a pronounced effect on the STRO-1+ hMSC population.

FIG. 2.

Supplementation with heparan sulfate-2 supports the expansion of stromal precursor antigen-1+ human mesenchymal stem cells. (A) FACS analysis confirms that early passage hMSCs express high levels of CD73 and CD105 and moderate levels of CD49a and stromal precursor antigen (STRO-1). (B) Continued subculturing in HS-2 (160 ng/mL) increases STRO-1 expression, (C) and the STRO-1Bright+ population. (D) Colony efficiency assays indicated that HS-2-expanded cells form ∼50% more colonies compared with cells cultured in control media. Error bars represent the standard deviation, n=3.

Human MSCs expanded long-term in HS-2 proliferate more readily yet retain their multipotency

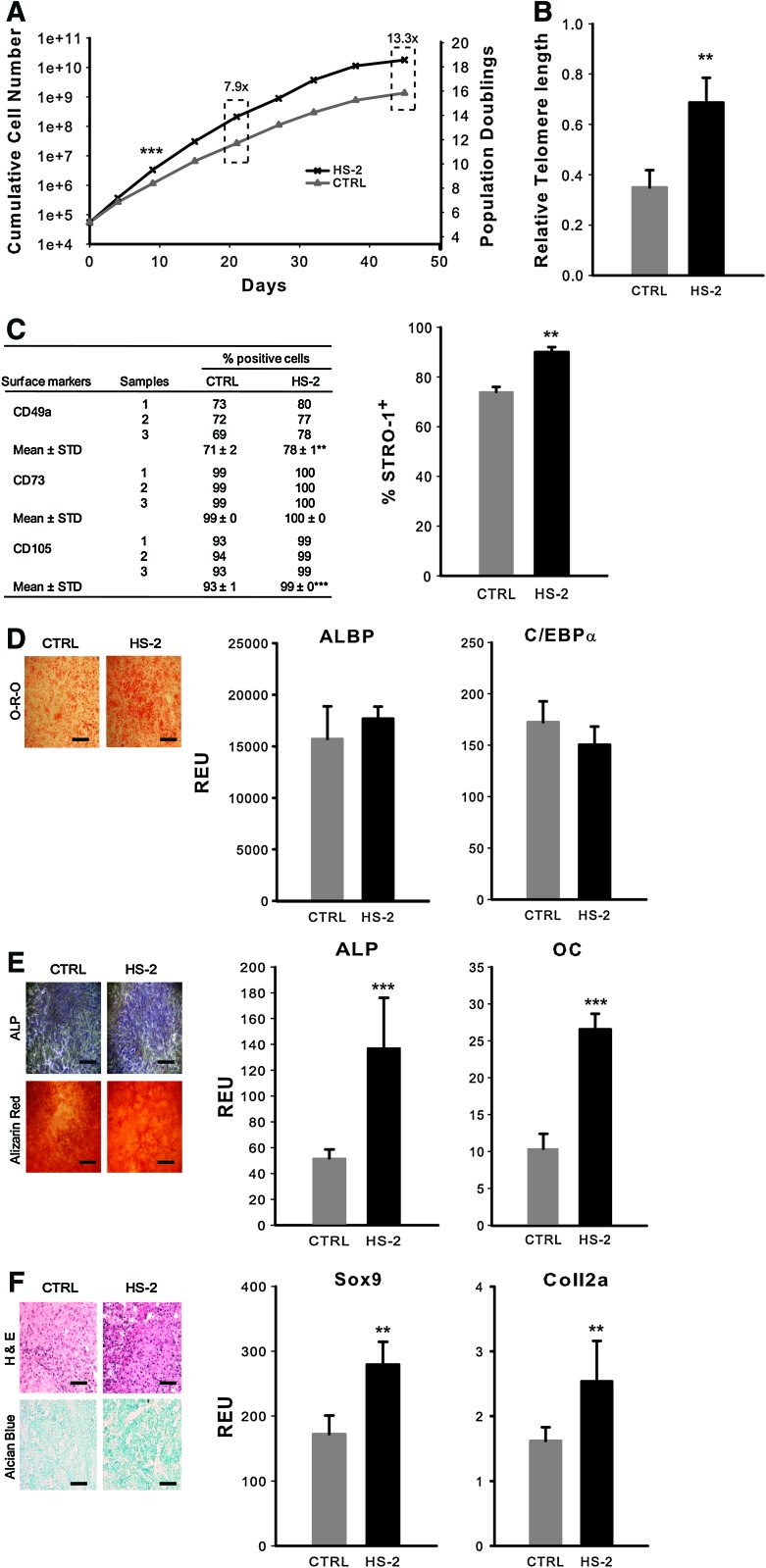

As HS-2 has a potent early effect on the growth of hMSC cultures, we next assessed its long-term effects. Expansion of hMSCs for clinical use typically requires cells to be cultured for up to 1 month to achieve a therapeutic dose [40,3]. We expanded hMSCs in either HS-2 or control media following established protocols [41]. Cultures supplemented with HS-2 resulted in ∼8-fold more cells than controls after only 21 days (Fig. 3A). To determine the long-term effect of HS-2 supplementation on hMSCs, we performed a series of assays that examined telomere length, CFU-F frequency, immunophenotype, and multilineage differentiation potential. Cells expanded for 15 population doublings in HS-2 had significantly longer telomeres than cells expanded in control media (Fig. 3B). After more than 18 population doublings, the HS-2-expanded cells had a longer average telomere length than the control cells after 15 population doublings (data not shown). Notably, no telomerase activity could be detected in these cells irrespective of the culture treatments (data not shown), as previously reported [23,24].

FIG. 3.

Heparan sulfate-2 enriches a subpopulation of more naïve human mesenchymal stem cells with longer telomeres during continuous subculturing. (A) hMSCs were expanded in control or HS-2 media for 45 days and the cumulative cell number plotted against time. (B) Relative telomere length of hMSCs expanded in control or HS-2 media for 15 population doublings (PD). (C) Expression of surface markers in hMSCs expanded ∼p7 in control or HS-2 media. (D–F) Differentiative potential of hMSCs continuously subcultured for ∼p7 in control or HS-2 media. Expanded cells were then differentiated for 28 days in adipogenic (D), osteogenic (E), or 21 days in chondrogenic media (F). Adipogenesis was measured by Oil-Red-O staining (Scale bar=1 mm) and quantitative PCR for CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-a (C/EBPa) and adipocyte lipid binding protein (ALBP); osteogenesis was measured by alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alizarin red staining (Scale bar=1 mm), and quantitative PCR for ALP and osteocalcin (OC); and chondrogenesis was measured by H&E and alcian blue staining (Scale bar=500 μm) and quantitative PCR for collagen2a1 (Coll2a) and SOX9. Error bars represent the standard deviation, n=3. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

To test whether prolonged exposure to HS-2 adversely affected hMSC phenotype, surface marker expression, and multipotentiality was analyzed after ∼40 days of serial culture. The expression of STRO-1, CD49a, and CD105 was significantly increased in the presence of HS-2, while CD73 remained unchanged (Fig. 3C). We next determined the adipogenic (Fig. 3D), osteogenic (Fig. 3E), and chondrogenic (Fig. 3F) potential of these cells when cultured in the appropriate differentiating media using a combination of histological and PCR-based approaches. Notably, HS-2-expanded cells had similar, or in some cases, increased multipotentiality compared with control. Moreover, the ability of these cells to enter either the osteogenic or chondrogenic lineage was particularly pronounced. These data show that HS-2 significantly increases the proliferation of a subpopulation of highly multipotent (STRO-1+) hMSCs that have longer telomeres.

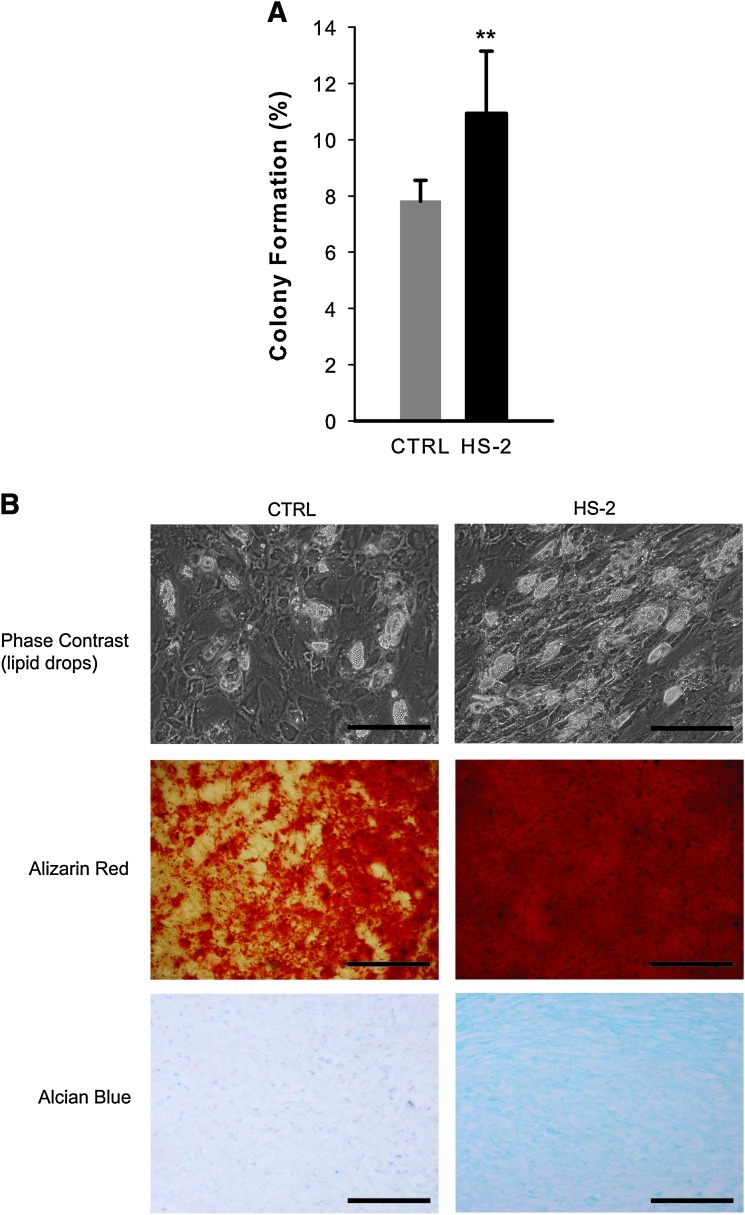

HS-2-expanded hMSCs have a higher frequency of CFU-Fs and are more multipotential after single cell cloning

To rigorously demonstrate that HS-2 supplementation is capable of targeting the expansion of mesenchymal stem cells, rather than a mixed population of progenitors, we evaluated colony formation and multipotentiality of single cell clones isolated from hMSCs previously expanded for 13 population doublings in either HS-2 or control media. Using the automated cell deposition unit of the flow cytometer, single cells were seeded into 96 multi-well plates and cultured for 2 weeks. The cells expanded in HS-2 showed higher rates of colony formation (1.4-fold) than cells in control media (Fig. 4A). The multilineage potential of parallel colonies was assessed by adipogenic (lipid accumulation), osteogenic (alizarin red staining), and chondrogenic (alcian blue staining) assay (Fig. 4B) and showed increased levels of differentiation in HS-2-expanded hMSCs. RQ-PCR analysis of adipocyte lipid-binding protein and alkaline phosphatase expression was also used to confirm the increased levels of differentiation in HS-2-expanded hMSCs (data not shown). These data further confirm that hMSCs expanded in the presence of HS-2 retain their multipotentiality over control cells expanded for the same number of population doublings.

FIG. 4.

Heparan sulfate-2 expands single cell hMSC clones that readily undergo multilineage differentiation. (A) Single cell colony formation of hMSCs pre-expanded in HS-2 or control media for 13 population doublings; (B) multilineage differentiation assays of representative clones from these colonies. From top to bottom: phase contrast micrographs of lipid containing cells from adipogenic cultures, alizarin red staining of mineralizing osteogenic cultures, and alcian blue staining of chondrogenic cultures. (Scale bars=200 μm). Error bars represent standard deviation, n= 3. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Expansion of hMSCs in HS-2 maintains their naïvety

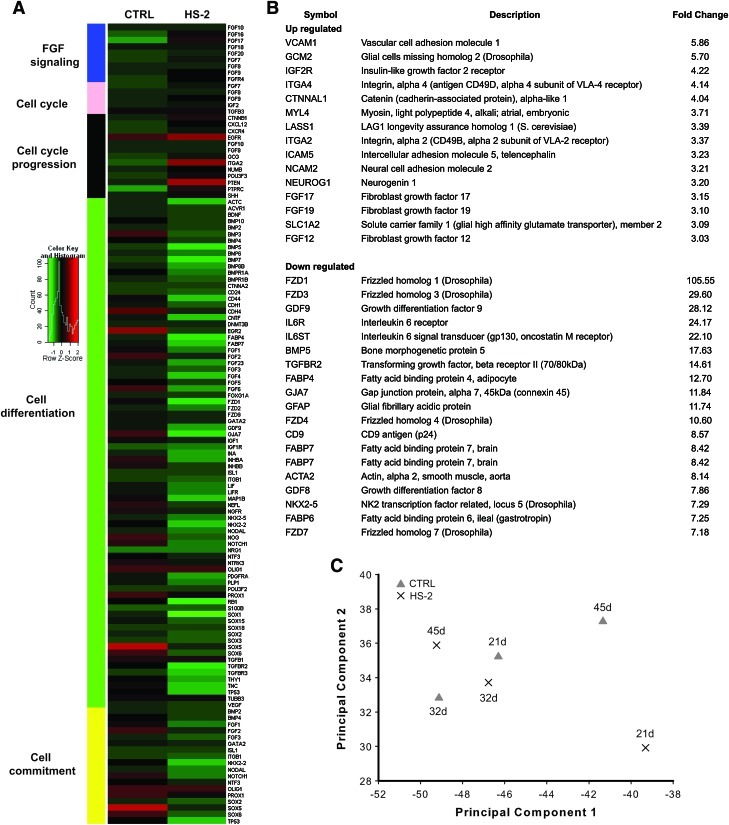

Measures of “stemness” in hMSCs are most often reported based on assessment of adherence to tissue culture plastic, immunophenotypic profile, multi-lineage assay [42] and in vivo bone formation [23]. Here, we also utilize gene profiling (Fig. 5A, B) and PCA [35] (Fig. 5C) of data obtained from a stem-cell specific array to assess stemness and classes of genes that together reflect different biological programs. A heat map based on hierarchical clustering by function revealed that groups of genes associated with cell cycle progression and mitogenic signaling were downregulated in controls, whereas gene sets involved in cell commitment and differentiation were downregulated in hMSCs expanded in HS-2. Our data suggest that groups of genes involved in cell adhesion and growth are collectively upregulated by HS-2 supplementation, while gene sets linked to Wnt and TGF signaling are downregulated.

FIG. 5.

Heparan sulfate-2 protects hMSC cultures against the temporal loss of the stem cell gene signature. (A) Heirarchical clustering and heat map analysis of genes expressed in hMSCs maintained in HS-2 or control media. (B) HS-2 supplementation upregulates genes involved in cell proliferation while downregulating those involved in differentiation. (C) Singular value decomposition of stem cell related genes for hMSC cultures in HS-2 or control media. Cells grown in HS-2 cluster with control cells from earlier cultures. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Array data was then projected onto the first two maximally-variant singular vectors to create an expression signature by SVD [43] (Fig. 5C). These data show that hMSCs expanded in the presence of HS-2 (crosses) for 21 days had a distinctive gene expression signature and did not cluster with cells from the other treatments, like control cells cultured for 45 days. However, clustering between cells cultured for 32 or 45 days in the presence of HS-2 and control cells at 21 or 32 days was apparent. This suggests that HS-2 yields a stem cell gene signature typical of younger control cells. To determine whether the HS-2 effect was robust, the stem cell gene expression signature at day 21 from 2 other donors was compared to the first donor. They also clustered together on the basis of treatment (data not shown). This indicates that the effects of HS-2 were not donor-specific, and that gene expression signatures produced by SVD can be used to reliably compare cells from different donors.

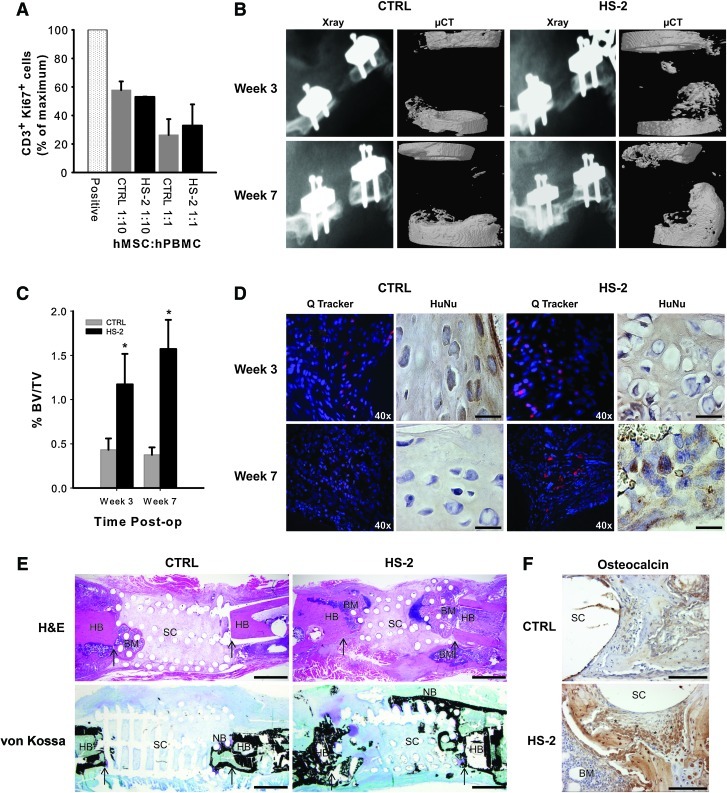

HS-2-expanded hMSCs are immunosuppressive and stimulate robust bone formation in critical-sized bone defects

As hMSCs have been shown to exert immunosuppressive effects [37], we examined whether continuous expansion in HS-2 had any adverse effect (Fig. 6A). Human MSCs were expanded for 21 days in either HS-2 or control media and then challenged with a mixture of stimulatory and reactionary PBMCs from two different donors at different hMSC: PBMC ratios for 6 days, after which CD3+ Ki67+ expression was assessed. HS-2 did not impair the immunosuppressive effects of the hMSCs, despite their greatly accelerated growth rate.

FIG. 6.

Human MSCs cultured in heparan sulfate-2 retain their immunomodulatory capabilities and augment bone formation when transplanted in vivo. (A) Immunomodulatory activity of hMSCs expanded in control or HS-2 supplemented media. A mixture of stimulatory and reactionary PBMCs from 2 different donors were added to wells at different hMSC:PBMC ratios and the expression of CD3+ Ki67+ assessed by FACS. The positive control represents the maximum number of CD3+ Ki67+ cells obtained in the absence of HS-2- or control-expanded hMSCs. Readings are in duplicate for each experiment and the graph is the mean±standard deviation (SD) of 2 separate experiments. (B) Representative X-ray and micro-computed tomography (μ-CT) images of 8 mm critical-sized nude rat femoral defects treated with transplanted HS-2- or control-expanded hMSCs after 3 and 7 weeks. (C) Percent bone volume in the defect site at weeks 3 and 7. Results are expressed as mean±SD, n=6 for each treatment group, per time point. Significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test * p<0.05. (D) Representative cryosections of defects revealing the surviving hMSCs. DAPI stains the nuclei of all cells blue, while the hMSCs prelabeled with QTracker® fluoresce red. (E) Representative histological sections of defects at week 7 stained with H&E and von Kossa. Arrows indicate the edges of host bone. NB: new bone, HB: host bone, BM: bone marrow, SC: scaffold. Scale bar=500 μm. (F) Magnification of representative defects at week 7 showing abundant osteocalcin-positive osteoblasts present within the newly regenerated bone. * indicate the border of osteoblasts slightly away from the scaffold pore. SC, scaffold; BM, bone marrow. Scale bar=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

We next examined whether long-term ex vivo expansion of hMSCs in HS-2 affected their therapeutic utility when transplanted into a clinically relevant in vivo bone defect model. Bone formation within the osseous defect was assessed by X-ray and μ-CT imaging at 3 and 7 weeks postsurgery and demonstrated that treatment of the bone defects with HS-2-expanded hMSCs resulted in greater deposition of new bone (2.8-fold at 3 weeks; 4.2-fold at 7 weeks) that was statistically significant based on a two-tailed unpaired t-test (p<0.05) (Fig. 6B, C). Bone bridging was not observed in any of the treated femurs, as this occurs only at later stages of bone regeneration that surpasses the 7-weeks healing window in this study.

To assess the in vivo survival of the implanted hMSCs, selected defects were treated with cells prelabeled with Qtracker® fluorescent nano-particles. At 3 weeks post-transplantation, labeled hMSCs (red fluorescent particles) were present within the bone defect site of all treated femurs (Fig. 6D). Notably, the cytoplasmic label (red fluorescent particles) was only found co-localized with DAPI-positive (blue) cells, confirming that it was retained by the transplanted hMSCs. Immunostaining with an antibody specific for human nuclei further verified the presence of surviving hMSCs within the site of bone repair, irrespective of hMSC culture conditions. By week 7, the only red fluorescent-labeled cells still present in the site of bone repair were from hMSCs expanded in HS-2.

The healing potential of the transplanted hMSCs was further verified 7 weeks postsurgery by histological assessment. H&E sections of bone repair sites receiving HS-2-expanded hMSCs revealed new bone-like tissue, bone marrow, and hypertrophic chondrocytes (indicating endochondral ossification) infiltrating the defect site from both the host bone interface and the subcutaneous interface (Fig. 6E). Von Kossa-stained sections confirmed the presence of mineralized bone-like tissue (stained black) in the HS-2 cell group that bridged the majority of the defect and infiltrated the scaffold pores (Fig. 6E). Similarly, osteocalcin-rich tissue was also evident within the bone repair site treated with HS-2-expanded cells (Fig. 6F). In contrast, defects treated with control-expanded hMSCs resulted in little mineralized tissue, and was largely devoid of von Kossa and osteocalcin staining (Fig. 6E, F). Thus HS-2-expanded hMSCs retain their ability to stimulate robust bone formation despite their extensive ex vivo expansion. Moreover, the enhanced survival of the HS-2-expanded hMSCs at the defect may have resulted in a larger or more persistent secretion of bioactive molecules, resulting in improved bone formation [8].

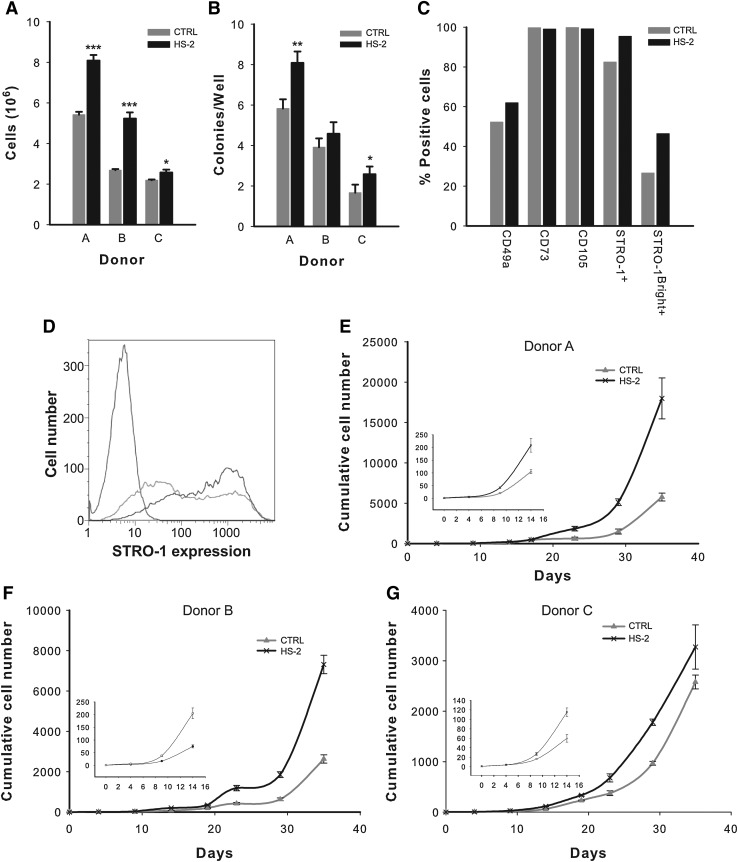

HS-2 robustly expands hMSCS isolated from unfractionated bone marrow aspirates

As HS-2 proved effective in the culture expansion of multipotent hMSCs, we next investigated whether cells directly isolated from unfractionated bone marrow also positively responded to HS-2 supplementation with a view to determining its direct clinical utility. Bone marrow aspirates derived from 3 separate healthy donors (Cambrex (Lonza) Lot numbers 2F1657, 4F0218, and 3F0664) contained plastic-adherent hMSCs that strongly responded to HS-2, both in terms of their proliferative capacity and their colony-forming ability (Fig. 7A, B) thus corroborating results obtained with established hMSC cultures (Figs. 1 and 2). Flow cytometric assessment revealed that none of the cells expressed the hematopoietic markers CD34 or CD45 (data not shown), but did express the hMSC markers CD49a, CD73, CD105, and STRO-1 (Fig. 7C, D). As the majority of the CFU-Fs derived from BMMNCs are contained within a subpopulation of cells with high STRO-1 expression (STRO-1Bright+)[11], we next determined the effect of HS-2 on the proportion of STRO-1Bright+ cells (Fig. 7C, D). The mean STRO-1Bright+ content in HS-2 expanded cells were 46.4% compared with 26.6% for cells expanded in control media (Fig. 7C, D). Hence, HS-2 preferentially promotes the expansion of a subpopulation of STRO-1+Bright hMSCs contained within bone marrow aspirates.

FIG. 7.

Exposure to heparan sulfate-2 increases the growth and frequency of colony forming units-fibroblastic in primary bone marrow aspirates and stimulates expansion of the stromal precursor antigen-1 positive subpopulation. (A) Colony growth from 3 different bone marrow donors in control or HS-2-containing media and (B) colony frequency in control and HS-2-containing media. (C) Representative example of surface marker expression from colonies recovered in control or HS-2-containing media. (D) STRO-1 expression from (C); isotype control is indicated by red line, control by green line, and STRO-1 by blue line showing increase in the STRO-1Bright+ population. (E–G) Cumulative growth of hMSCs from 3 different primary bone marrow donors in HS-2 or control supplemented media.

To further assess the ability of HS-2 to expand hMSCs, low passage cells from the 3 donors were continuously cultured for 35 days in the presence or absence of HS-2 (Fig. 7E–G). In all 3 cases, supplementation with HS-2 greatly accelerated the cumulative increase in cell numbers in line with the previous results on established hMSCs cultures (Fig. 1 and 2). Moreover, the growth advantage of HS-2 supplementation was observed as early as 8 days in culture (graph inserts), irrespective of donor.

Discussion

The results of this study show that an embryonic HS, HS-2, can be used to preference the rapid expansion of hMSCs without the need for prospective immunosorting, or the use of a variable cocktail of protein factors that invariably results in heterogeneous cultures. Further, these HS-2-expanded hMSCs display superior therapeutic utility when transplanted into a clinically relevant model of orthopedic trauma. Therefore, administration of HS-2 is particularly attractive as a strategy to selectively enrich and then propagate the most therapeutically desirable hMSC subpopulation.

Current strategies employed to generate hMSCs for clinical use rely on their isolation by adherence to plastic, followed by lengthy ex vivo expansion before their reimplantation. This process is required due to the extremely low frequency of hMSCs in adult bone marrow [3]. This is further exacerbated by both the age-related loss in hMSC growth potential, with the associated loss in telomere length [32] and the fact that many hMSCs remain quiescent when isolated and cultured. As such, strategies that allow for the ex vivo expansion of this particular bone marrow subpopulation are required to achieve efficacious treatment. To address this need, a range of isolation and expansion methodologies have been used in trials, including prospective immunoselection with a range of mAb to antigens that include STRO-1 [11], SSEA-4 [13], CD49a [44], CD146 [45], LNGFR/CD271 [46], and VCAM-1 [47], culture expansion with factors such as FGF-2 [16,21] and the use of platelet-derived products [18] and defined specialty medias [48]. Notwithstanding extensive research into these strategies, they are not yet widely accepted.

Of the targets for immunoselection, the STRO-1+ subpopulation has been shown to enrich clonogenic stromal cells (CFU-Fs) by as much as 10-fold [12] but this selection requires lengthy cell sorting procedures. In contrast, HS-2 treatment that avoids mAb-based preselection, not only increased the proportion of hMSCs expressing STRO-1 from ∼50% to ∼80% (including the STRO-1Bright+ subpopulation), but also the frequency of CFU-Fs by ∼50%, after only 1 passage. Further, HS-2-expansion yields hMSCs that are more phenotypically similar to hMSCs from younger cultures as evidenced by their longer telomeres, genetic signature, and multilineage potential. Notably human fetal MSCs grow faster and have longer telomeres than adult hMSCs [32]. Thus, in a therapeutic setting where large-scale expansion of hMSCs is required to obtain an efficacious dose, the presence of HS-2 would act to rapidly increase the proportion of STRO-1+ cells in a given dose of hMSCs. Moreover, as HS-2 increases the expansion of STRO-1+ hMSCs that are known to be a more potent source of paracrine factors (compared to conventional hMSCs) [12], the use of HS-2-expanded hMSCs may further expedite healing and overcome the current limitations of existing hMSC therapies.

We also observed a modest time-dependent increase (∼1.6-fold) in the basal expression of both CD49a and STRO-1 in cultures passaged in the absence of HS-2. This observation suggests that plastic adherence may contribute to the positive selection of multipotent cells that respond to HS-2. The biological co-expression of CD49a and STRO-1 is consistent with the previous findings that CFU-Fs express both these markers [49–51].

To address the in vivo potential of HS-2 in bone repair, critical-sized bone defects were treated with HS-2-expanded hMSCs and showed greatly improved bone repair, with the transplanted cells surviving within the defect site for up to 7 weeks. Notably, appreciable new bone formation was observed as early as 3 weeks post-transplantation during bone repair with HS-2-expanded hMSCs (∼2.5-fold greater than with control hMSCs), yet without the treatment variability associated with cell heterogeneity that we and others have previously reported using hMSCs propagated by conventional methods [12,13,37]. Further, no increase in bone volume within the defect site was observed between 3 and 7 weeks post-treatment with control hMSCs, suggestive of a failed implant. By comparison, defects treated with HS-2-expanded hMSCs continued to deposit new bone within the bone repair site, indicating a sustained therapeutic advantage. The use of HS-2 to expand hMSCs also precluded the need to predifferentiate the cells, a strategy that appears to improve healing outcomes in some models [52]. Of particular note is that despite achieving large-scale expansion of multipotent hMSCs using HS-2 supplementation, these cells retain their immunosuppressive capabilities; [8] an ability that is associated with higher chances of survival in vivo [53].

Exogenous FGF-2 has been shown to regulate hMSC self-renewal, but its long-term use also increases their heterogeneity [21], and upregulates HLA-class I and induces low HLA-DR expression [54]. These observations impair its clinical use by increasing the likelihood of variation to the extent of bone healing. More recently, collagen IV was shown to select for cultured, but undifferentiated MSCs [55]. In contrast, we show that continuous supplementation with HS-2 similarly upregulates hMSC self-renewal and greatly improves their homogeneity, suggesting that HS-2 would benefit future therapies utilizing cultured hMSCs. Importantly, these highly charged HS molecules can be extracted and purified through a series of well-established enzymatic, chemical, and chromatographic steps that mitigate against infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, and prions. In contrast to protein growth factors, HS is resilient to a range of bioprocessing procedures, being thermally stable and chemically resistant, making it well suited not only as a culture supplement but also for a range of biomedical applications.

Conclusion

Our study shows that HS-2 supplementation maintains the utility of hMSCs through repeated passaging without any concomitant loss of stemness, across multiple donors. Moreover, by increasing the homogeneity of hMSC transplants, therapies that employ HS-2-expanded hMSCs may improve efficacy in bone regeneration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Biomedical Research Council of A*STAR (Agency for Science, Technology, and Research), Singapore and the Institutes of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB) and Medical Biology (IMB), A*STAR, Singapore. We thank Zer Cheng Phua, and the A*STAR BSF histology and FACS core facilities for their technical assistance. We also express our gratitude to the Bioinformatics Institute (BII), A*STAR, Singapore, for the provision of computational resources.

References

- 1.Jiang Y. Jahagirdar BN. Reinhardt RL. Schwartz RE. Keene CD. Ortiz-Gonzalez XR. Reyes M. Lenvik T. Lund T, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner J. Kean T. Young R. Dennis JE. Caplan AI. Optimizing mesenchymal stem cell-based therapeutics. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittenger MF. Martin BJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and their potential as cardiac therapeutics. Circ Res. 2004;95:9–20. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000135902.99383.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyahara Y. Nagaya N. Kataoka M. Yanagawa B. Tanaka K. Hao H. Ishino K. Ishida H. Shimizu T, et al. Monolayered mesenchymal stem cells repair scarred myocardium after myocardial infarction. Nat Med. 2006;12:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nm1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petite H. Viateau V. Bensaid W. Meunier A. de Pollak C. Bourguignon M. Oudina K. Sedel L. Guillemin G. Tissue-engineered bone regeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:959–963. doi: 10.1038/79449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quarto R. Mastrogiacomo M. Cancedda R. Kutepov SM. Mukhachev V. Lavroukov A. Kon E. Marcacci M. Repair of large bone defects with the use of autologous bone marrow stromal cells. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:385–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Blanc K. Rasmusson I. Sundberg B. Gotherstrom C. Hassan M. Uzunel M. Ringden O. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–1441. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meirelles Lda S. Fontes AM. Covas DT. Caplan AI. Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedenstein AJ. Chailakhjan RK. Lalykina KS. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1970;3:393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1970.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colter DC. Sekiya I. Prockop DJ. Identification of a subpopulation of rapidly self-renewing and multipotential adult stem cells in colonies of human marrow stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7841–7845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141221698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gronthos S. Simmons PJ. The growth factor requirements of STRO-1-positive human bone marrow stromal precursors under serum-deprived conditions in vitro. Blood. 1995;85:929–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Psaltis PJ. Paton S. See F. Arthur A. Martin S. Itescu S. Worthley SG. Gronthos S. Zannettino AC. Enrichment for STRO-1 expression enhances the cardiovascular paracrine activity of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cell populations. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:530–540. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gang EJ. Bosnakovski D. Figueiredo CA. Visser JW. Perlingeiro RC. SSEA-4 identifies mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow. Blood. 2007;109:1743–1751. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-010504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ringden O. Uzunel M. Rasmusson I. Remberger M. Sundberg B. Lonnies H. Marschall HU. Dlugosz A. Szakos A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of therapy-resistant graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2006;81:1390–1397. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000214462.63943.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boland GM. Perkins G. Hall DJ. Tuan RS. Wnt 3a promotes proliferation and suppresses osteogenic differentiation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93:1210–1230. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solchaga LA. Penick K. Porter JD. Goldberg VM. Caplan AI. Welter JF. FGF-2 enhances the mitotic and chondrogenic potentials of human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203:398–409. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamama K. Fan VH. Griffith LG. Blair HC. Wells A. Epidermal growth factor as a candidate for ex vivo expansion of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:686–695. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doucet C. Ernou I. Zhang Y. Llense JR. Begot L. Holy X. Lataillade JJ. Platelet lysates promote mesenchymal stem cell expansion: a safety substitute for animal serum in cell-based therapy applications. J Cell Physiol. 2005;205:228–236. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Digirolamo CM. Stokes D. Colter D. Phinney DG. Class R. Prockop DJ. Propagation and senescence of human marrow stromal cells in culture: a simple colony-forming assay identifies samples with the greatest potential to propagate and differentiate. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:275–281. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izadpanah R. Kaushal D. Kriedt C. Tsien F. Patel B. Dufour J. Bunnell BA. Long-term in vitro expansion alters the biology of adult mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4229–4238. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh S. Jefferiss C. Stewart K. Jordan GR. Screen J. Beresford JN. Expression of the developmental markers STRO-1 and alkaline phosphatase in cultures of human marrow stromal cells: regulation by fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 and relationship to the expression of FGF receptors 1–4. Bone. 2000;27:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quarto N. Wan DC. Longaker MT. Molecular mechanisms of FGF-2 inhibitory activity in the osteogenic context of mouse adipose-derived stem cells (mASCs) Bone. 2008;42:1040–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi S. Gronthos S. Chen S. Reddi A. Counter CM. Robey PG. Wang CY. Bone formation by human postnatal bone marrow stromal stem cells is enhanced by telomerase expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:587–591. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonsen JL. Rosada C. Serakinci N. Justesen J. Stenderup K. Rattan SI. Jensen TG. Kassem M. Telomerase expression extends the proliferative life-span and maintains the osteogenic potential of human bone marrow stromal cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauney JR. Kirker-Head C. Abrahamson L. Gronowicz G. Volloch V. Kaplan DL. Matrix-mediated retention of in vitro osteogenic differentiation potential and in vivo bone-forming capacity by human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells during ex vivo expansion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:464–475. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns JS. Abdallah BM. Guldberg P. Rygaard J. Schroder HD. Kassem M. Tumorigenic heterogeneity in cancer stem cells evolved from long-term cultures of telomerase-immortalized human mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3126–3135. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brickman YG. Ford MD. Gallagher JT. Nurcombe V. Bartlett PF. Turnbull JE. Structural modification of fibroblast growth factor-binding heparan sulfate at a determinative stage of neural development. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4350–4359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher JT. Heparan sulfate: growth control with a restricted sequence menu. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:357–361. doi: 10.1172/JCI13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurcombe V. Ford MD. Wildschut JA. Bartlett PF. Developmental regulation of neural response to FGF-1 and FGF-2 by heparan sulfate proteoglycan. Science. 1993;260:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.7682010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rider DA. Dombrowski C. Sawyer AA. Ng GH. Leong D. Hutmacher DW. Nurcombe V. Cool SM. Autocrine fibroblast growth factor 2 increases the multipotentiality of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1598–1608. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guillot PV. Gotherstrom C. Chan J. Kurata H. Fisk NM. Human first-trimester fetal MSC express pluripotency markers and grow faster and have longer telomeres than adult MSC. Stem Cells. 2007;25:646–654. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghosh D. Resampling methods for variance estimation of singular value decomposition analyses from microarray experiments. Funct Integr Genomics. 2002;2:92–97. doi: 10.1007/s10142-002-0047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bild AH. Yao G. Chang JT. Wang Q. Potti A. Chasse D. Joshi MB. Harpole D. Lancaster JM, et al. Oncogenic pathway signatures in human cancers as a guide to targeted therapies. Nature. 2006;439:353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villanueva J. Shaffer DR. Philip J. Chaparro CA. Erdjument-Bromage H. Olshen AB. Fleisher M. Lilja H. Brogi E, et al. Differential exoprotease activities confer tumor-specific serum peptidome patterns. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:271–284. doi: 10.1172/JCI26022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang da W. Sherman BT. Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rai B. Lin JL. Lim ZX. Guldberg RE. Hutmacher DW. Cool SM. Differences between in vitro viability and differentiation and in vivo bone-forming efficacy of human mesenchymal stem cells cultured on PCL-TCP scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7960–7970. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawyer AA. Song SJ. Susanto E. Chuan P. Lam CX. Woodruff MA. Hutmacher DW. Cool SM. The stimulation of healing within a rat calvarial defect by mPCL-TCP/collagen scaffolds loaded with rhBMP-2. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2479–2488. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dombrowski C. Song SJ. Chuan P. Lim X. Susanto E. Sawyer AA. Woodruff MA. Hutmacher DW. Nurcombe V. Cool SM. Heparan sulfate mediates the proliferation and differentiation of rat mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:661–670. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruder SP. Jaiswal N. Ricalton NS. Mosca JD. Kraus KH. Kadiyala S. Mesenchymal stem cells in osteobiology and applied bone regeneration. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355(Suppl):S247–S256. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaiswal N. Haynesworth SE. Caplan AI. Bruder SP. Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 1997;64:295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dominici M. Le Blanc K. Mueller I. Slaper-Cortenbach I. Marini F. Krause D. Deans R. Keating A. Prockop D. Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The international society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alter O. Brown PO. Botstein D. Singular value decomposition for genome-wide expression data processing and modeling. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10101–10106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rider DA. Nalathamby T. Nurcombe V. Cool SM. Selection using the alpha-1 integrin (CD49a) enhances the multipotentiality of the mesenchymal stem cell population from heterogeneous bone marrow stromal cells. J Mol Histol. 2007;38:449–458. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9128-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi S. Gronthos S. Perivascular niche of postnatal mesenchymal stem cells in human bone marrow and dental pulp. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:696–704. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones E. McGonagle D. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in vivo. Rheumatology. 2008;47:126–131. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gronthos S. Zannettino AC. Hay SJ. Shi S. Graves SE. Kortesidis A. Simmons PJ. Molecular and cellular characterisation of highly purified stromal stem cells derived from human bone marrow. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1827–1835. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hudson JE. Mills RJ. Frith JE. Brooke G. Jaramillo-Ferrada P. Wolvetang EJ. Cooper-White JJ. A defined medium and substrate for expansion of human mesenchymal stromal cell progenitors that enriches for osteo- and chondrogenic precursors. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:77–87. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boiret N. Rapatel C. Veyrat-Masson R. Guillouard L. Guerin JJ. Pigeon P. Descamps S. Boisgard S. Berger MG. Characterization of nonexpanded mesenchymal progenitor cells from normal adult human bone marrow. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deschaseaux F. Charbord P. Human marrow stromal precursors are alpha 1 integrin subunit-positive. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:319–325. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200009)184:3<319::AID-JCP5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart K. Monk P. Walsh S. Jefferiss CM. Letchford J. Beresford JN. STRO-1, HOP-26 (CD63), CD49a and SB-10 (CD166) as markers of primitive human marrow stromal cells and their more differentiated progeny: a comparative investigation in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;313:281–290. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0762-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peters A. Toben D. Lienau J. Schell H. Bail HJ. Matziolis G. Duda GN. Kaspar K. Locally applied osteogenic predifferentiated progenitor cells are more effective than undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of delayed bone healing. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2947–2954. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stenderup K. Justesen J. Eriksen EF. Rattan SI. Kassem M. Number and proliferative capacity of osteogenic stem cells are maintained during aging and in patients with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1120–1129. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.6.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sotiropoulou PA. Perez SA. Salagianni M. Baxevanis CN. Papamichail M. Characterization of the optimal culture conditions for clinical scale production of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:462–471. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andersen DC. Kortesidis A. Zannettino AC. Kratchmarova I. Chen L. Jensen ON. Teisner B. Gronthos S. Jensen CH. Kassem M. Development of novel monoclonal antibodies that define differentiation stages of human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cells. Mol Cells. 2011;32:133–142. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-2277-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]