Abstract

The lymphoid system is equipped with a network of specialized platforms located at strategic sites, which grant strict immune-surveillance and efficient immune responses. The development of these peripheral secondary lymphoid organs (SLO) occurs mainly in utero, while tertiary lymphoid structures can form in adulthood generally in response to persistent infection and inflammation. Regardless of the lymphoid tissue and intrinsic cellular and molecular differences, it is now well established that the recruitment of fully functional lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells to presumptive lymphoid organ sites, and their consequent close and reciprocal interaction with resident stroma cells, are central to SLO formation. In contrast, the nature of events that initially prime resident sessile stroma cells to recruit and retain LTi cells remains poorly understood. Recently, new findings revealed early phases of SLO development putting emphasis on mesenchymal and lymphoid tissue initiator cells. Herein we discuss the main tenets of enteric lymphoid organs genesis and focus in the most recent findings that open new perspectives to the understanding of the early phases of lymphoid morphogenesis.

Keywords: enteric lymphoid organ morphogenesis, stroma cells, LTin cells

INTRODUCTION

The lymphoid system possesses highly specialized peripheral organs formed at strategic anatomical sites that constitute three-dimensional platforms ensuring efficient immune-surveillance, rapid immune responses and maintenance of protective immunity. Secondary lymphoid organs (SLO), such as lymph nodes (LN) and Peyer’s patches (PP), develop during the embryonic life, but can also assemble after birth as it occurs with enteric cryptopatches and isolated lymphoid follicles (Randall et al., 2008; Eberl and Sawa, 2010; van de Pavert and Mebius, 2010; Neyt et al., 2012).

Remarkably, while LN develop at strictly invariable locations along lymphatic vessels, PP develop in variable number and position in the anti-mesenteric side of the mid-intestine (5–12 in mice; Nishikawa et al., 2003). Similarly, cryptopatches appear confined to intestinal lamina propria but they also distribute randomly within the gut wall (Kanamori et al., 1996). Despite these intrinsic differences, SLO development relies on an antigen-independent process where presumptive regions are colonized by lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells that cross-talk with resident mesenchymal cells through lymphotoxin (LT) α1β2 and LTβ receptor (LTβR) interactions, thus creating a positive feed-back loop that culminates on the anlagen formation.

Although the mechanisms of SLO development have been extensively characterized throughout the years (Randall et al., 2008; van de Pavert and Mebius, 2010; Cupedo, 2011), most studies have been powerless to scrutinize early events preceding LTi cell colonization and clustering. Thus, putative early triggering events preceding LTi cell ingress into lymphoid organ anlagen remain poorly understood (Nishikawa et al., 2003).

GENESIS OF LYMPHOID ORGAN PRIMORDIA: THE LTi PARADIGM

Fetal hematopoietic cells colonize pre-defined sites between embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) and 16.5 (E16.5) according to the type and location of the prospective lymphoid organ (Rennert et al., 1996; Adachi et al., 1998; Mebius et al., 2001; Yoshida et al., 2001; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007; Possot et al., 2011; Tachibana et al., 2011; Cherrier et al., 2012). Hematopoietic cells include CD3-CD4-/+cKit+IL7Rα+α4β7+Rorγt+/- LTi cells (Kelly and Scollay, 1992; Adachi et al., 1997, 1998; Mebius et al., 1997; Yoshida et al., 1999; Sawa et al., 2010; Possot et al., 2011; Cherrier et al., 2012) and a distinct population of CD3-CD4-cKit+IL7Rα-CD11c+ lymphoid tissue initiator (LTin) cells (Hashi et al., 2001; Fukuyama and Kiyono, 2007; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2012). PP development depends on LTi and LTin cells, while LN genesis relies on LTi cells although the role of LTin in LN formation remains elusive. Upon arrival to prospective sites, LTin and LTi cells are believed to establish an interplay with their mesenchymal cell counterparts, lymphoid tissue organizers (LTo) cells, in order to trigger lymphoid organ formation.

The presence of fully functional LTi and LTin cells is necessary for the development of enteric SLO. Absence of LTi cells, as described in mice deficient for Ikaros, Inhibitor of DNA-binding 2 (Id2), retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γ t (Rory t), and RUNT-related transcription factor 1 (Runx1)/core-binding factor, beta 2 subunit (Cbfb2), result in PP developmental failure (Wang et al., 1996; Yokota et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2000; Tachibana et al., 2011). Similarly, depletion of LTin cells or deficiency of Ret expression on these cells results in impaired PP formation (Fukuyama and Kiyono, 2007; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007).

Lymphoid tissue inducer cells express the chemokine receptors CXCR5 and CCR7 that specifically bind to the homeostatic chemokines CXCL13 and CCL21/19, respectively. These chemokines create gradients that coordinate LTi cell migration and colonization of presumptive lymphoid organ sites (Forster et al., 1996, 1999; Honda et al., 2001; Luther et al., 2003; Mebius, 2003). In addition, the expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and MAdCAM-1 by stroma organizer cells ensures retention of hematopoietic cells through the ligation of the integrin receptors α4β1 and α4β7 expressed by LTi and LTin cells surface (Mebius et al., 1996; Hashi et al., 2001; Finke et al., 2002; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Thus, it is commonly accepted that chemokines and adhesion molecules contribute to a productive and persistent communication between hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells (van de Pavert and Mebius, 2010).

The engagement of LTα1β2 expressed by LTi cells with stromal cell LTβR leads to activation of the classical and alternative NF-κB signaling pathways, which are critical to stroma cell maturation and lymphoid organ development (Weih et al., 1995; Yamada et al., 2000; Alcamo et al., 2001, 2002; Paxian et al., 2002; Yilmaz et al., 2003; Carragher et al., 2004; Lovas et al., 2008). In agreement, mice deficient for LTα, LTβ, LTβR, or molecular players of the NF-κB signaling pathways fail to develop LN and PP (Rennert et al., 1996, 1997, 1998).

The activation of LTβR results in the maturation of stroma cells, inducing the expression of adhesion molecules MAdCAM-1, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 (Cuff et al., 1999; Dejardin et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2002; Ame-Thomas et al., 2007; Vondenhoff et al., 2009a), as well as the homeostatic chemokines CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL13 (Ansel et al., 2000; Luther et al., 2003). In addition, IL-7 and TRANCE induce the expression of LTα1β2 and generate a positive feed-back loop that sustains a continuous supply of signals between stroma and LTi cells granting maturation of the former (Ansel et al., 2000; Honda et al., 2001; Yoshida et al., 2002; Luther et al., 2003; Mebius, 2003).

MATURATION OF MESENCHYMAL CELLS: THE STROMACENTRIC VIEW

The general mechanism of SLO development, whereby LTi cells colonize lymphoid organ primordia, is similar among PP and LN anlagen (Yoshida et al., 2002; Randall et al., 2008; van de Pavert and Mebius, 2010; Cupedo, 2011). However, despite the obvious parallels there are also remarkable differences between the morphogenesis of these organs. Examples of such differential processes are provided by IL7/IL7R and TRANCE/TRANCE-R signaling. Thus, while IL7R signal is critical to PP development, as revealed by Il7r-/- mice, brachial, axillary, and mesenteric LN develop normally in these animals (Adachi et al., 1998; Yoshida et al., 1999; Luther et al., 2003). Furthermore, while in Trance-/- and Traf6-/- mice LN development is severely compromised, PP form normally in these mice (Dougall et al., 1999; Naito et al., 1999). Finally, the tyrosine kinase receptor RET also plays a differential role in LN and PP genesis. This is revealed by the absence of PP in Ret null embryos, which have seemingly normal LN anlagen development (Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007).

Interestingly, mesenchymal organizer cells from LN and PP also exhibit distinctive genetic features (Yoshida et al., 2002; Cupedo et al., 2004; Okuda et al., 2007). This genetic heterogeneity, suggests that LTo cells may also provide different cues to hematopoietic cells. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the acquisition of such divergent genetic profiles are cell autonomous or derived from paracrine cellular interaction with different hematopoietic cell subsets.

The distribution of mesenchymal cells within lymphoid organs differs between PP and LN. In the intestine, stromal cells are distributed throughout the gut tissue that becomes colonized by highly motile hematopoietic cells between day E12.5 and E15.5. At this stage rare VCAM-1+ cells are detected in the gut wall (Adachi et al., 1997). However, by E16.5, VCAM-1+/ICAM-1+ clusters of stroma cells are clearly visible forming PP primordia (Adachi et al., 1997; Yoshida et al., 1999; Hashi et al., 2001; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Conversely, LN invariably develop within lymph sacs, where ICAM-1+VCAM-1+ mesenchymal stromal cells initially surround endothelial cells and by E16.5 start to invade the endothelium core to form a proper compartment of the anlagen (Okuda et al., 2007). Surprisingly, although lymphatic endothelial cells are essential to the correct formation of LN and lymphatic vasculature, they are dispensable for the initial aggregation of LTi and LTo cells (Cupedo et al., 2004; Vondenhoff et al., 2009b; Benezech et al., 2010).

Interestingly, mounting evidence indicates that LTo cells are very heterogeneous. In PP genesis, VCAM-1+/ICAM-1+ organizer cells express LTβR, CCL19, and CXCL13 (Adachi et al., 1997; Yoshida et al., 1999; Hashi et al., 2001; Honda et al., 2001; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007), and further analysis revealed that this cell population comprises VCAM-1inICAM-1in and VCAM-1hiICAM-1hi subpopulations (Okuda et al., 2007). Similarly, these populations were also identified in LN (Cupedo et al., 2004; Okuda et al., 2007; Benezech et al., 2010). The comparison of genetic expression between PP and LN VCAM-1hiICAM-1hi cells shows that mesenteric LN LTo cells have surface expression of TRANCE, whereas their PP counterparts lack the expression of this ligand (Cupedo et al., 2004; Okuda et al., 2007). Furthermore, microarray analysis revealed that their genetic signatures are distinct. Mesenteric LN stroma cells express significantly higher levels of cytokines and chemokines such as IL6, IL7, CCL7, CXCL1, and CCL11 (Okuda et al., 2007). Conversely, the homeostatic chemokines CCL21, CCL19, and CXCL13 are more abundant in enteric stroma cells. Interestingly, genes implicated in morphogenesis, such as Meox2, Lhx8, and Prrx1, were significantly higher in mesenteric LN when compared to PP counterparts, yet their functional relevance in lymphoid organogenesis is unclear (Okuda et al., 2007).

In addition to previously described VCAM-1inICAM-1in and VCAM-1hiICAM-1hi stroma cells, another population of VCAM-1negICAM-1neg, expressing PDGFRα but gp38/podoplanin and VEGFR3 negative was identified in LN (Benezech et al., 2010). Although, VCAM-1inICAM-1in and VCAM-1hiICAM-1hi cells have been described in PP, the existence of a VCAM-1negICAM-1neg counterpart remains to be investigated (Cupedo et al., 2004; Okuda et al., 2007). VCAM-1negICAM-1neg stroma cells express Ccl21 and Tnfr1 while VCAMhiICAMhi express the highest levels of Ccl21, Ccl19, Cxcl13, Trance, and Il7, as compared with VCAM-1inICAM-1in, confirming their greater potential to attract LTi (Cupedo et al., 2004; Okuda et al., 2007; Benezech et al., 2010). Interestingly, the treatment of LN with αLTβR Ab agonist significantly increased the frequency of VCAM-1hiICAM-1hi cells (Benezech et al., 2010). In addition, Ltbr-/- and Rorc(γt)-/- mice absolutely lacked these VCAM-1hiICAM-1hi cells in inguinal and mesenteric LN (Benezech et al., 2010), thus confirming the implication of LTi cells and the engagement of LTβR on the maturation of residential stroma cells. Surprisingly, the emergence of VCAM-1inICAM-1in is seemingly normal in the absence of LTβR and LTi cells (White et al., 2007; Benezech et al., 2010). These data indicate that while the maturation of VCAM-1inICAM-1in into VCAM-1hiICAM-1hi absolutely depends on LTβR and LTi cells, the transition from VCAM-1loICAM-1lo to VCAM-1inICAM-1in is LTβR and LTi cell independent (Benezech et al., 2010). These conclusions are supported by the fact that the recruitment of LTi cells to lymphoid organ is observed in the absence of LTβR signaling (Yoshida et al., 2002; Coles et al., 2006; Vondenhoff et al., 2009a; Benezech et al., 2010), and by the LTβR-independent expression of homeostatic chemokines CCL21 and CXCL13, and the cytokine IL7 (Ansel et al., 2000; Luther et al., 2003; Cupedo et al., 2004; Moyron-Quiroz et al., 2004; Benezech et al., 2010). Finally, while agonist anti-LTβR treatment rescues LN development in LTα-/- mice, the same treatment in LTi deficient Rorc(γt)-/- mice, fail to promote SLO development (Rennert et al., 1998; Eberl et al., 2004). Altogether, these observations suggest that early LTβR-independent events precede LTi cell arrival, initiating a specific genetic expression profile in mesenchymal cells.

In agreement with this hypothesis, it was shown that CXCL13 can be induced by the vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid independently of LTα1β2/LTβR signaling (van de Pavert et al., 2009). Interestingly, analysis of mice deficient for RALDH-2, a crucial retinoic acid-synthesizing enzyme, revealed that at E14.5 the majority of LN were absent and CXCL13 expression was undetectable (van de Pavert et al., 2009). Additionally, neurons-expressing RALDH-1/2 were observed near the LN anlagen, suggesting potential neuronal source of retinoic acid (van de Pavert et al., 2009). Whether this signaling axis has a functional relevance for PP development remains unclear. However, Gdnf and Gfra1 null embryos fail to develop a myenteric nervous system but still have normal PP development arguing against such hypothesis (Moore et al., 1996; Cacalano et al., 1998; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the presence of parasympathetic and/or sympathetic neurons still present in the guts of these mutants, may provide such retinoic acid cues for PP formation. Interestingly, given the role of retinoic acid role in intestinal immune responses, a direct effect of retinoic acid in LTin and/or LTi cell subsets cannot be discarded at this stage (Hall et al., 2011a,b).

THE EARLY PRIMING EVENTS OF ENTERIC SLO: THE LTin CELL REIGN

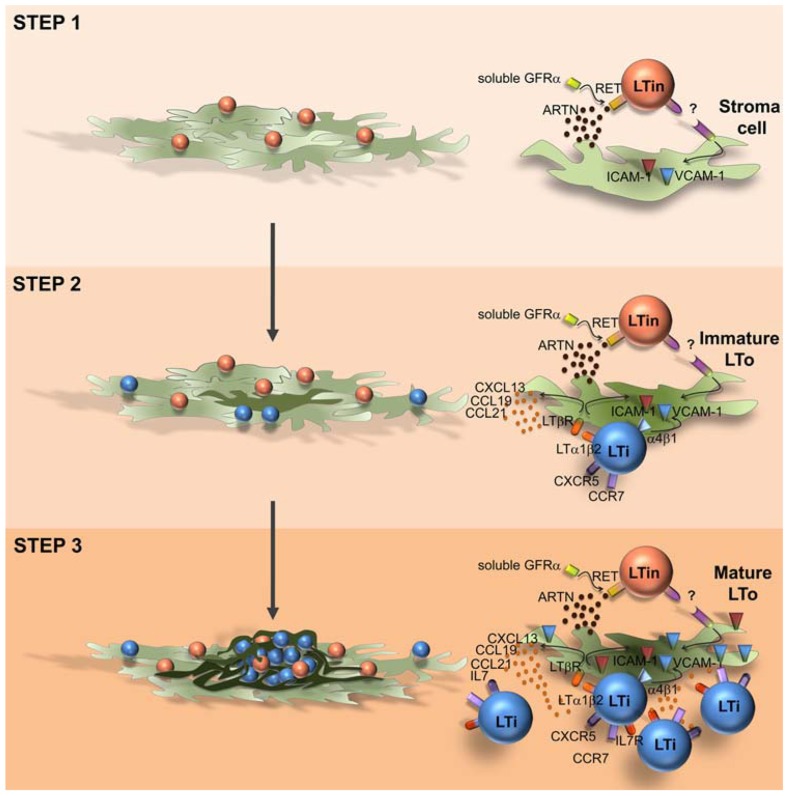

In the intestine CD3-CD4+IL7Rα+ LTi cells and VCAM-1+/ICAM-1+ stromal organizer cells cluster together with CD3-CD4-IL7Rα-cKit+CD11c+ cells (Fukuyama and Kiyono, 2007; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Mice partly depleted of CD3-CD4-IL7Rα-cKit+CD11c+ cells have impaired PP development and mice deficient for the receptor tyrosine kinase RET (Ret-/-), expressed by this population do not develop PP (Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Thus, CD3-CD4-IL-7Rα-cKit+ CD11c+ cells were suggested to be involved in early phases of enteric lymphoid tissue formation and were named LTin cells (Fukuyama and Kiyono, 2007; Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Supporting this concept, the RET ligand ARTN induces the formation of ectopic lymphoid structures, and LTin cells are the first hematopoietic cellular entity to cluster together with VCAM-1 expressing stroma cells (Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007; Patel et al., 2012). Although, LTi cells are scarcely detected at very early phases of enteric organ formation, an extensive accumulation of LTi cells occurs subsequently to LTin cell aggregation (Patel et al., 2012). Interestingly, LTin cells respond unconventionally in trans to all RET ligands, reducing their motility upon contact with mesenchymal cells, in an adhesion-dependent manner (Patel et al., 2012). Furthermore, while Ccl19, Ccl21, and Cxcl13 chemokine expression is not required in this early triggering phase, VCAM-1 blockage results in a profound reduction of cell clustering efficiency, indicating that subsequent up-regulation of VCAM-1 in stroma organizer cells is essential to recruit and retain the first coming LTi cells (Patel et al., 2012). Thus, in opposition to the LTi action mechanism, where chemokines and LT/LTβR are key (Hashi et al., 2001; Finke et al., 2002; Luther et al., 2003; Ohl et al., 2003), LTin cells act at very early phases determining early maturation of enteric mesenchymal cells in a RET-dependent, chemokine-independent manner (Patel et al., 2012). Strikingly, in agreement with previous reports in the LN, the initial induction of VCAM-1 expression in enteric stroma cells might not rely on the engagement of LTβR, since RET ligand stimulation does not up-regulate LTβ on LTin cells and blockage of LTβR signaling does not impair VCAM-1 induction on stromal cells (Patel et al., 2012). Thus, we would like to propose that PP development is a multi-step, multi-cellular process relying on an initial RET-dependent and adhesion-dependent interaction between LTin and mesenchymal cells, which result in stroma cell priming, ultimately leading to efficient LTi cell recruitment (Figure 1). Although, CD11c+ cells have been detected in anlagen LN, Ret-/- mice develop peripheral LN (Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Thus it remains unknown whether LTin cells are also implicated in early stroma cell priming of LN. LTin cells have been phenotypically characterized. These cells present some features of dendritic cells, expressing CD11c, CD11b, and MHC class II, but lack DEC205 and express NK1.1 and Gr-1 (Veiga-Fernandes et al., 2007). Thus, it would be very interesting to understand the precursor-product relationship between LTin cells and other cell lineages. Finally, it would be exceedingly exciting to determine whether LTin and RET responses may also initiate enteric cryptopatches or lymphoid tissue induced in chronic inflammation.

FIGURE 1.

Model of Peyer’s patch development. Peyer’s patch development relies on a multi-step, multi-cellular process. Step 1: RET-dependent, adhesion-dependent interaction between LTin and mesenchymal cells, results in stroma cell priming and VCAM1 induction (immature LTo cell). Step 2: retention of resident LTi cells through a VCAM1 mediated process; LTi/LTo interaction through LTαβ/ LTβR inducing a chemokine and adhesion molecule competent LTo cell (mature LTo cell). Step 3: Positive feed-back loop generating fully mature LTo cells and additional LTi cell recruitment and retention into the primordium.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Over the last two decades, remarkable findings have consolidated our knowledge on lymphoid organogenesis. Despite differences between diverse lymphoid organs, we can now appreciate that recruitment of fully functional LTi cells is central in LN and PP organogenesis and that, upon their arrival, an intimate and productive cross-talk is established with stroma cells. However, new insights have recently shed light on early initiating events that imprint stroma cells to create an attractive milieu for LTi cell recruitment. These findings emphasize a subtle phase, yet crucial to enteric stroma cell maturation, this is the step where LTin cells reign. We foresee the identification of early key players to stroma cell priming in adulthood and inflammatory settings as important challenges in the future.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Manuela Ferreira was supported by a scholarships from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal. Rita G. Domingues was supported by a project grant from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (PTDC/SAU-MII/104931/2008), Portugal. Henrique Veiga-Fernandes was partly supported by European Molecular Biology Organisation (Project 1648) and European Research Council (Project 207057).

REFERENCES

- Adachi S., Yoshida H., Honda K., Maki K., Saijo K., Ikuta K., Saito T., Nishikawa S. I. (1998). Essential role of IL-7 receptor alpha in the formation of Peyer’s patch anlage. Int. Immunol. 10 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi S., Yoshida H., Kataoka H., Nishikawa S. (1997). Three distinctive steps in Peyer’s patch formation of murine embryo. Int. Immunol. 9 507– 514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo E., Hacohen N., Schulte L. C., Rennert P. D., Hynes R. O., Baltimore D. (2002). Requirement for the NF-kappaB family member RelA in the development of secondary lymphoid organs. J. Exp. Med. 195 233–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo E., Mizgerd J. P., Horwitz B. H., Bronson R., Beg A. A., Scott M., Doerschuk C. M., Hynes R. O., Baltimore D. (2001). Targeted mutation of TNF receptor I rescues the RelA-deficient mouse and reveals a critical role for NF-kappa B in leukocyte recruitment. J. Immunol. 167 1592– 1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ame-Thomas P., Maby-El Hajjami H., Monvoisin C., Jean R., Monnier D., Caulet-Maugendre S., Guillaudeux T., Lamy T., Fest T., Tarte K. (2007). Human mesenchymal stem cells isolated from bone marrow and lymphoid organs support tumor B-cell growth: role of stromal cells in follicular lymphoma pathogenesis. Blood 109 693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansel K. M., Ngo V. N., Hyman P. L., Luther S. A., Forster R., Sedgwick J. D., Browning J. L., Lipp M., Cyster J. G. (2000). A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature 406 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benezech C., White A., Mader E., Serre K., Parnell S., Pfeffer K., Ware C. F., Anderson G., Caamano J. H. (2010). Ontogeny of stromal organizer cells during lymph node development. J. Immunol. 184 4521–4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacalano G., Farinas I., Wang L. C., Hagler K., Forgie A., Moore M., Armanini M., Phillips H., Ryan A. M., Reichardt L. F., Hynes M., Davies A., Rosenthal A. (1998). GFRalpha1 is an essential receptor component for GDNF in the developing nervous system and kidney. Neuron 21 53–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher D., Johal R., Button A., White A., Eliopoulos A., Jenkinson E., Anderson G., Caamano J. (2004). A stroma-derived defect in NF-kappaB2-/- mice causes impaired lymph node development and lymphocyte recruitment. J. Immunol. 173 2271–2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier M., Sawa S., Eberl G. (2012). Notch, Id2, and RORgammat sequentially orchestrate the fetal development of lymphoid tissue inducer cells. J. Exp. Med. 209 729–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles M. C., Veiga-Fernandes H., Foster K. E., Norton T., Pagakis S. N., Seddon B., Kioussis D. (2006). Role of T and NK cells and IL7/IL7r interactions during neonatal maturation of lymph nodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 13457–13462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuff C. A., Sacca R., Ruddle N. H. (1999). Differential induction of adhesion molecule and chemokine expression by LTalpha3 and LTalphabeta in inflammation elucidates potential mechanisms of mesenteric and peripheral lymph node development. J. Immunol. 162 5965–5972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupedo T. (2011). Human lymph node development: an inflammatory interaction. Immunol. Lett. 138 4–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupedo T., Vondenhoff M. F., Heeregrave E. J., De Weerd A. E., Jansen W., Jackson D. G., Kraal G., Mebius R. E. (2004). Presumptive lymph node organizers are differentially represented in developing mesenteric and peripheral nodes. J. Immunol. 173 2968–2975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin E., Droin N. M., Delhase M., Haas E., Cao Y., Makris C., Li Z. W., Karin M., Ware C. F., Green D. R. (2002). The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity 17 525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougall W. C., Glaccum M., Charrier K., Rohrbach K., Brasel K., De Smedt T., Daro E., Smith J., Tometsko M. E., Maliszewski C. R., Armstrong A., Shen V., Bain S., Cosman D., Anderson D., Morrissey P. J., Peschon J. J., Schuh J. (1999). RANK is essential for osteoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev. 13 2412–2424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., Marmon S., Sunshine M. J., Rennert P. D., Choi Y., Littman D. R. (2004). An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat. Immunol. 5 64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G., Sawa S. (2010). Opening the crypt: current facts and hypotheses on the function of cryptopatches. Trends Immunol. 31 50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke D., Acha-Orbea H., Mattis A., Lipp M., Kraehenbuhl J. (2002). CD4+CD3- cells induce Peyer’s patch development: role of alpha4beta1 integrin activation by CXCR5. Immunity 17 363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R., Mattis A. E., Kremmer E., Wolf E., Brem G., Lipp M. (1996). A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell 87 1037–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R., Schubel A., Breitfeld D., Kremmer E., Renner-Muller I., Wolf E., Lipp M. (1999). CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell 99 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama S., Kiyono H. (2007). Neuroregulator RET initiates Peyer’s-patch tissue genesis. Immunity 26 393–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. A., Cannons J. L., Grainger J. R., Dos Santos L. M., Hand T. W., Naik S., Wohlfert E. A., Chou D. B., Oldenhove G., Robinson M., Grigg M. E., Kastenmayer R., Schwartzberg P. L., Belkaid Y. (2011a). Essential role for retinoic acid in the promotion of CD4(+) T cell effector responses via retinoic acid receptor alpha. Immunity 34 435–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. A., Grainger J. R., Spencer S. P., Belkaid Y. (2011b). The role of retinoic acid in tolerance and immunity. Immunity 35 13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashi H., Yoshida H., Honda K., Fraser S., Kubo H., Awane M., Takabayashi A., Nakano H., Yamaoka Y., Nishikawa S. (2001). Compartmentalization of Peyer’s patch anlagen before lymphocyte entry. J. Immunol. 166 3702–3709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K., Nakano H., Yoshida H., Nishikawa S., Rennert P., Ikuta K., Tamechika M., Yamaguchi K., Fukumoto T., Chiba T., Nishikawa S. I. (2001). Molecular basis for hematopoietic/mesenchymal interaction during initiation of Peyer’s patch organogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 193 621–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori Y., Ishimaru K., Nanno M., Maki K., Ikuta K., Nariuchi H., Ishikawa H. (1996). Identification of novel lymphoid tissues in murine intestinal mucosa where clusters of c-kit+ IL-7R+ Thy1+ lympho-hemopoietic progenitors develop. J. Exp. Med. 184 1449–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K. A., Scollay R. (1992). Seeding of neonatal lymph nodes by T cells and identification of a novel population of CD3-CD4+ cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 22 329–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovas A., Radke D., Albrecht D., Yilmaz Z. B., Moller U., Habenicht A. J., Weih F. (2008). Differential RelA- and RelB-dependent gene transcription in LTβR-stimulated mouse embryonic fibroblasts. BMC Genomics 9 606 10.1186/1471-2164-9-606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther S. A., Ansel K. M., Cyster J. G. (2003). Overlapping roles of CXCL13, interleukin 7 receptor alpha, and CCR7 ligands in lymph node development. J. Exp. Med. 197 1191–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebius R. E. (2003). Organogenesis of lymphoid tissues. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3 292–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebius R. E., Miyamoto T., Christensen J., Domen J., Cupedo T., Weissman I. L., Akashi K. (2001). The fetal liver counterpart of adult common lymphoid progenitors gives rise to all lymphoid lineages, CD45+CD4+CD3- cells, as well as macrophages. J. Immunol. 166 6593–6601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebius R. E., Rennert P., Weissman I. L. (1997). Developing lymph nodes collect CD4+CD3- LTbeta+ cells that can differentiate to APC, NK cells, and follicular cells but not T or B cells. Immunity 7 493–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebius R. E., Streeter P. R., Michie S., Butcher E. C., Weissman I. L. (1996). A developmental switch in lymphocyte homing receptor and endothelial vascular addressin expression regulates lymphocyte homing and permits CD4+CD3- cells to colonize lymph nodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 11019–11024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. W., Klein R. D., Farinas I., Sauer H., Armanini M., Phillips H., Reichardt L. F., Ryan A. M., Carver-Moore K., Rosenthal A. (1996). Renal and neuronal abnormalities in mice lacking GDNF. Nature 382 76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyron-Quiroz J. E., Rangel-Moreno J., Kusser K., Hartson L., Sprague F., Goodrich S., Woodland D. L., Lund F. E., Randall T. D. (2004). Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat. Med. 10 927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito A., Azuma S., Tanaka S., Miyazaki T., Takaki S., Takatsu K., Nakao K., Nakamura K., Katsuki M., Yamamoto T., Inoue J. (1999). Severe osteopetrosis, defective interleukin-1 signalling and lymph node organogenesis in TRAF6-deficient mice. Genes Cells 4 353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyt K., Perros F., Geurtsvankessel C. H., Hammad H., Lambrecht B. N. (2012). Tertiary lymphoid organs in infection and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 33 297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa S., Honda K., Vieira P., Yoshida H. (2003). Organogenesis of peripheral lymphoid organs. Immunol. Rev. 195 72–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl L., Henning G., Krautwald S., Lipp M., Hardtke S., Bernhardt G., Pabst O., Forster R. (2003). Cooperating mechanisms of CXCR5 and CCR7 in development and organization of secondary lymphoid organs. J. Exp. Med. 197 1199–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda M., Togawa A., Wada H., Nishikawa S. (2007). Distinct activities of stromal cells involved in the organogenesis of lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. J. Immunol. 179 804–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, Harker N., Moreira-Santos L., Ferreira M., Alden K., Timmis J., Foster K., Garefalaki A., Pachnis P., Andrews P., Enomoto H., Milbrandt J., Pachnis V., Coles M. C., Kioussis D., Veiga-Fernandes H. (2012). Differential RET signaling pathways drive development of the enteric lymphoid and nervous systems. Sci. Signal 5 ra55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxian S., Merkle H., Riemann M., Wilda M., Adler G., Hameister H., Liptay S., Pfeffer K., Schmid R. M. (2002). Abnormal organogenesis of Peyer’s patches in mice deficient for NF-kappaB1, NF-kappaB2, and Bcl-3. Gastroenterology 122 1853–1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possot C., Schmutz S., Chea S., Boucontet L., Louise A., Cumano A., Golub R. (2011). Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORgammat(+) innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 12 949–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall T. D., Carragher D. M., Rangel-Moreno J. (2008). Development of secondary lymphoid organs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26 627–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennert P. D., Browning J. L., Hochman P. S. (1997). Selective disruption of lymphotoxin ligands reveals a novel set of mucosal lymph nodes and unique effects on lymph node cellular organization. Int. Immunol. 9 1627–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennert P. D., Browning J. L., Mebius R., Mackay F., Hochman P. S. (1996). Surface lymphotoxin alpha/beta complex is required for the development of peripheral lymphoid organs. J. Exp. Med. 184 1999–2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennert P. D., James D., Mackay F., Browning J. L., Hochman P. S. (1998). Lymph node genesis is induced by signaling through the lymphotoxin beta receptor. Immunity 9 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa S., Cherrier M., Lochner M., Satoh-Takayama N., Fehling H. J., Langa F., Di Santo J. P., Eberl G. (2010). Lineage relationship analysis of RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Science 330 665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Unutmaz D., Zou Y. R., Sunshine M. J., Pierani A., Brenner-Morton S., Mebius R. E., Littman D. R. (2000). Requirement for RORgamma in thymocyte survival and lymphoid organ development. Science 288 2369–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M., Tenno M., Tezuka C., Sugiyama M., Yoshida H., Taniuchi I. (2011). Runx1/Cbfbeta2 complexes are required for lymphoid tissue inducer cell differentiation at two developmental stages. J. Immunol. 186 1450–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Pavert S. A., Mebius R. E. (2010). New insights into the development of lymphoid tissues. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10 664–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Pavert S. A., Olivier B. J., Goverse G., Vondenhoff M. F., Greuter M., Beke P., Kusser K., Hopken U. E., Lipp M., Niederreither K., Blomhoff R., Sitnik K., Agace W. W., Randall T. D., de Jonge W. J., Mebius R. E. (2009). Chemokine CXCL13 is essential for lymph node initiation and is induced by retinoic acid and neuronal stimulation. Nat. Immunol. 10 1193–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-Fernandes H., Coles M. C., Foster K. E., Patel A., Williams A., Natarajan D., Barlow A., Pachnis V., Kioussis D. (2007). Tyrosine kinase receptor RET is a key regulator of Peyer’s patch organogenesis. Nature 446 547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vondenhoff M. F., Greuter M., Goverse G., Elewaut D., Dewint P., Ware C. F., Hoorweg K., Kraal G., Mebius R. E. (2009a). LTbetaR signaling induces cytokine expression and up-regulates lymphangiogenic factors in lymph node anlagen. J. Immunol. 182 5439–5445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vondenhoff M. F., van de Pavert S. A., Dillard M. E., Greuter M., Goverse G., Oliver G., Mebius R. E. (2009b). Lymph sacs are not required for the initiation of lymph node formation. Development 136 29–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. H., Nichogiannopoulou A., Wu L., Sun L., Sharpe A. H., Bigby M., Georgopoulos K. (1996). Selective defects in the development of the fetal and adult lymphoid system in mice with an Ikaros null mutation. Immunity 5 537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weih F., Carrasco D., Durham S. K., Barton D. S., Rizzo C. A., Ryseck R. P., Lira S. A., Bravo R. (1995). Multiorgan inflammation and hematopoietic abnormalities in mice with a targeted disruption of RelB, a member of the NF-kappa B/Rel family. Cell 80 331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A., Carragher D., Parnell S., Msaki A., Perkins N., Lane P., Jenkinson E., Anderson G., Caamano J. H. (2007). Lymphotoxin a-dependent and -independent signals regulate stromal organizer cell homeostasis during lymph node organogenesis. Blood 110 1950–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Mitani T., Yorita K., Uchida D., Matsushima A., Iwamasa K., Fujita S., Matsumoto M. (2000). Abnormal immune function of hemopoietic cells from alymphoplasia (aly) mice, a natural strain with mutant NF-kappa B-inducing kinase. J. Immunol. 165 804–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz Z. B., Weih D. S., Sivakumar V., Weih F. (2003). RelB is required for Peyer’s patch development: differential regulation of p52-RelB by lymphotoxin and TNF. EMBO J. 22 121–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota Y., Mansouri A., Mori S., Sugawara S., Adachi S., Nishikawa S., Gruss P. (1999). Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature 397 702–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Honda K., Shinkura R., Adachi S., Nishikawa S., Maki K., Ikuta K., Nishikawa S. I. (1999). IL-7 receptor alpha+ CD3(-) cells in the embryonic intestine induces the organizing center of Peyer’s patches. Int. Immunol. 11 643–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Kawamoto H., Santee S. M., Hashi H., Honda K., Nishikawa S., Ware C. F., Katsura Y., Nishikawa S. I. (2001). Expression of alpha(4)beta(7) integrin defines a distinct pathway of lymphoid progenitors committed to T cells, fetal intestinal lymphotoxin producer, NK, and dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 167 2511–2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Naito A., Inoue J., Satoh M., Santee-Cooper S. M., Ware C. F., Togawa A., Nishikawa S. (2002). Different cytokines induce surface lymphotoxin-alphabeta on IL-7 receptor-alpha cells that differentially engender lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. Immunity 17 823–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]