ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Mental illness is common and associated with poor outcomes for co-occurring medical illness. Since primary care physicians manage the treatment of complex patients with both mental and medical illnesses, their perspectives on the care of these patients is vital to improving clinical outcomes.

OBJECTIVE

To examine physician perceptions of patient, physician and system factors that affect the care of complex patients with mental and medical illness.

DESIGN

Inductive, participatory, team-based qualitative analysis of transcripts of in-depth semi-structured interviews.

PARTICIPANTS

Fifteen internal medicine physicians from two university primary care clinics and three community health clinics.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics were balanced in terms of years in practice, practice site, and gender. Physicians identified contributing factors to the complexity of patient care within the domains of patient, physician and system factors. Physicians identified 1) type of mental illness, 2) acuity of mental illness, and 3) communication styles of individual patients as the principal patient characteristics that affected care. Physicians expressed concern regarding their own lack of medical knowledge, clinical experience, and communication skills in treating mental illness. Further, they discussed tensions between professionalism and emotional responses to patients. Participants expressed great frustration with the healthcare system centered on: 1) lack of mental health resources, 2) fragmentation of care, 3) clinic procedures, and 4) the national healthcare system.

CONCLUSIONS

Physicians in this study made a compelling case for increased training in the treatment of mental illness and improvements in the delivery of mental health care. Participants expressed a strong desire for increased integration of care through collaboration between primary care providers and mental health specialists. This approach could improve both comfort in treating mental illness and the delivery of care for complex patients.

KEY WORDS: mental health services, comorbidity, ambulatory care, qualitative research

BACKGROUND

Mental illness is pervasive in the United States (US)1 with up to one-third of primary care patients suffering from depression.2 Mental illness significantly affects outcomes in patients with other chronic medical illnesses.3–10 The concept of patient complexity, which encompasses the influences of multiple chronic diseases, demographic factors, and psychosocial issues on disease outcomes,11,12 could prove helpful in understanding the interplay between co-occurring mental and medical illness. Although researchers have studied the deleterious effect of mental illness on medical illnesses, the experiences of providers and the clinical context in which they work to care for complex patients need further elucidation.

Mental illness is commonly treated in primary care: 43–60% of treatment for mental illness occurs in primary care and 17–20% in specialty mental health settings.13–16 Further, generalist providers prescribe over 70% of antidepressants.17 Since primary care physicians manage the treatment of complex patients with both mental and medical illnesses, understanding their perspectives on the challenges and facilitators of their care is critical to improving clinical outcomes for these patients. Qualitative methods that explore the clinical experiences, attitudes, and values of primary care physicians can provide vital insights into the context of findings of poor outcomes in patients with co-occurring mental and physical illness.18 Prior qualitative research has explored provider experiences with multimorbidity19 and mental illness20,21 in primary care separately. However, to our knowledge, no previous qualitative studies have investigated provider experiences with complex patients with co-occurring mental and medical illness.

Through open-ended interviews with primary care general internists, we sought to advance the current understanding of specific factors that may complicate day-to-day primary care of complex patients with mental illness. This study was designed to examine physician perceptions of the patient, physician and system factors that affect the care of complex patients with mental and medical illness.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Recruitment

In this qualitative study we conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews. We limited our study to internal medicine physicians to increase consistency in their training background. We recruited 15 physicians from two university clinics and three community health clinics associated with the University of Colorado School of Medicine. The community health clinics are part of a safety net hospital network. After three initial pilot interviews, we invited participation by sending email notices to all physicians in the practices, including 34 and 28 physicians from the university and the community health clinics, respectively. We used systematic non-probabilistic sampling22 to achieve an even distribution with respect to gender, years in practice, and type of practice.

Interviews

We developed an interview guide (Appendix) to explore physician experiences in the care of complex patients in general and, more specifically, complex patients with mental illness. Interview questions were refined with input from qualitative and health services researchers, interviewers, and physicians enrolled in initial pilot interviews. Interview questions addressed the following domains: patient factors, physician perceptions of competency, and healthcare system issues.23 In order to facilitate this discussion, physicians were asked to bring de-identified notes from three patients they considered complex to refer to in the interview. Before the interview, we emailed providers the following definition of complexity:

A complex patient is defined as a person with two or more chronic conditions where each condition may influence the care of the other condition. This patient may have other factors such as age, race, gender and psychosocial issues that also influence the morbidity associated with their chronic conditions …

The primary investigator (D.F.L.), a primary care physician, and another member of the research team, a communication doctoral candidate (C.C.), conducted the interviews July 2010 through December 2010. The one-on-one interview format was selected to encourage participants to express their feelings candidly and preserve confidentiality.24 Participants were not compensated. Interviews were conducted in a private space chosen by the participant and lasted approximately 60 minutes. They were digitally recorded, uploaded to a secure drive, and professionally transcribed. Participants did not review the transcripts. Saturation was achieved after ten interviews, so we completed the interview process after 15 interviews.

Analysis

Interview transcripts and a demographic survey were our primary data sources. Transcript files were entered into qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). We used an inductive, participatory, team-based approach to explore patterns and themes related to the care of patients with mental illness within the interview data.25–28 D.F.L. performed initial coding using an inductive coding approach.25,29 Codes were initially broadly categorized according to three domains of patient care explored in the interviews: patient, physician and healthcare system factors.23 Then, two other team-members (I.A.B and E.A.B) independently coded two of the interviews. They worked with D.F.L. to resolve differences and create the final codebook. Other team members (C.C. and F.D.) reviewed a subset of transcripts and met with the PI and other coders to discuss emerging themes and discrepancies.

This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

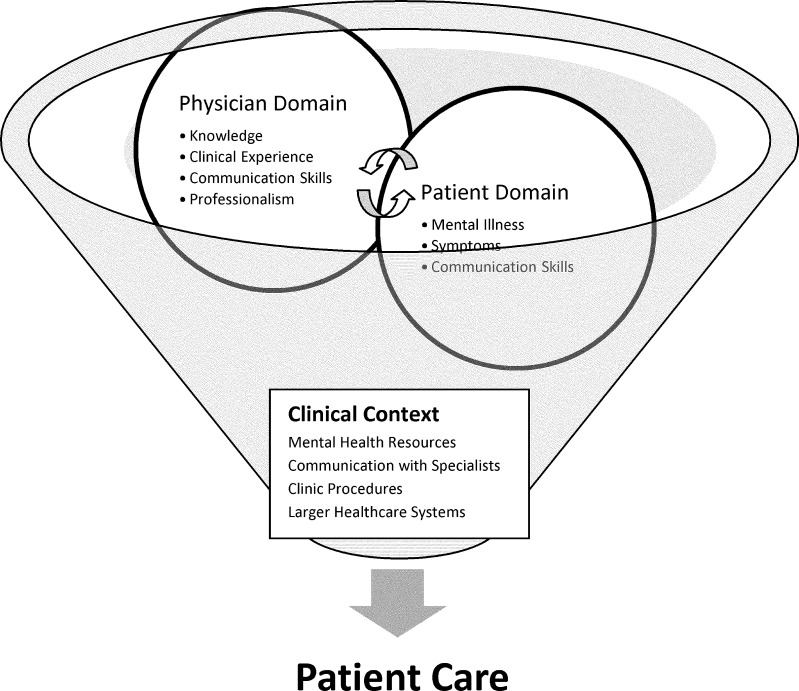

Participant characteristics were balanced in terms of years in practice, practice site, and gender (Table 1). Major themes emerged inductively within each of the three domains of patient care explored in the interviews. Physician and patient factors emerged in relationship to each other within the context of the clinical setting, which had a moderating effect on both the patient and physician factors. We developed a conceptual model to illustrate these interactions (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n = 15)

| Age in y mean (range) | 38 (29-52) |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 9 (60) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White Non-Hispanic, n (%) | 12 (80) |

| Asian, n (%) | 2 (13) |

| White Hispanic, n (%) | 1 (7) |

| Site of Practice | |

| Community Health v. University, n (%) | 7 (47) |

| Time since residency completion in y, mean (range) | 8 (<1-24) |

| Time in primary care practice in y, mean (range) | 7 (<1-24) |

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Patient Characteristics

Participants focused on major patient characteristics that increased complexity: 1) type of mental illness, 2) acuity of mental illness, and 3) communication styles.

Physicians expressed greater comfort treating common diagnoses, such as depression and anxiety, than serious mental illnesses. They also repeatedly cited patients with personality disorders as the most difficult to treat.

I think we are great at prescribing anti-depressants and doing PHQ-9 type scores and addressing unipolar depression … diagnosing and treating other mental illness - anything bipolar or schizoaffective or schizophrenia … I think most internists feel out of their league in terms of doing those things reliably. (I-1)

Participants felt the acuity of the symptoms of mental illness was strongly related to the complicating effect of the mental illness on care of medical illness. Symptoms such as anxiety, paranoid ideation, and poor motivation were cited as interfering with effective delivery of care of medical illness and medication adherence.

I think if the mental health problem is active, then that makes treating all the other medical problems that much more difficult … They may have a paranoid ideation about medicines or about physicians. Or they may be depressed so it is too difficult for them to go to the pharmacy to pick up a new medicine. Or they may be so anxious that they can't deal with one more new problem. (I-5)

Physicians also identified ways in which symptoms of mental illness affected patients’ communication skills. Some internists described patients with confrontational styles that led to difficulties at all levels of care.

[A] patient of mine who has, I suspect, mild, untreated schizophrenia … Anytime she gets a call from the hospital, she ends up cussing them out and telling them to leave her alone … On top of that she has a condition that needs to be monitored periodically and if it is not monitored appropriately could be fatal. (I-4)

Others described frustration when they could not understand their patients’ descriptions of symptoms. This physician felt that patient anxiety over their physical symptoms complicated medical decision-making.

I think everything gets magnified … For example, somebody who has heart failure and depression says I'm having chronic chest pain or I'm having palpitations or I'm having trouble breathing. So you wonder, my god, is it the heart failure? Is it COPD? They had a remote history of DVT in the 1970's, is this a PE now? And so I think they bring in these somatic things that can distract you and confuse you and mislead the work up. (I-11)

In summary, emergent themes included the following: 1) diagnoses of mild depression and anxiety added less complexity than other types of mental illnesses, 2) active symptoms of mental illness were significant drivers of complexity, and 3) patients whose mental illness symptoms interfered with their ability to communicate effectively were particularly challenging to care for, especially within a complex healthcare system.

Physician Competency

Four primary themes emerged in terms of physician competency: 1) medical knowledge, 2) clinical experience in caring for patients with mental illness, 3) communication skills in managing challenging patient-physician interactions, and 4) difficulty managing emotional responses to patients.

Physicians uniformly discussed deficiencies in their training in the treatment of mental illness. Most physicians felt that in treating patients with mental illness they were often operating beyond their scope of their training.

[E]ven though I feel I'm pretty good about asking about [mental illness], and about providing what support I can, I still feel pretty unconfident about … side effects of medication. And … should I be starting something? (I-9)

Physicians separated their level of knowledge in diagnosis and treatment of mental illness from their clinical skills. They felt more experience with patients during training was necessary to acquire the necessary skills to treat the types of mental illness they encountered in practice.

I think we learn a lot about diseases in medical school, but rarely do you connect that to what it is actually like to be a patient … you learn about schizophrenia and you learn about when people have hallucinations and you learn that they have auditory hallucinations, but that is so different than being in a room with somebody who is crying because the people [auditory hallucinations] won't leave her alone. (I-6)

Some physicians felt that communication skills were more important than medical knowledge. They were interested in acquiring skills to improve their ability to managing challenging patient interactions.

I think more than learning that these are the mental illnesses and this is how you treat them … strategies for dealing with patients with mental illness … what are some ways that you are able to get information from them without having them go off on a tangent … [as well as] …. strategies for how to deal with patients with personality disorders or who are really anxious. (I-3)

Participants differed in their attitudes toward treating mental illness. Further, a tension between maintaining professionalism, in terms of the fundamental principle of the “primacy of patient welfare”,30 while simultaneously managing emotional responses emerged. Some physicians expressed difficulty coping with their own emotional reaction to their patients.

Patients that remind me of my mother, that have these personality disorders and they are manipulative. Those people drive me nuts. (I-5)

Alternatively, other physicians consciously worked to maintain empathy for patients with mental illness, even those with confrontational communication styles.

(I)t's like … I wish this would really just be over so I could move on to something that's easier! And yet, the reality is that the whole rest of the system is dealing with them like that. And it is a human being who needs care and so I feel like I have to put in a double effort to be their advocate and make sure their mental illness doesn't prevent them from getting what they need. (I-4)

A common, though not universal, theme was that general internists enjoyed treating challenging medical illness but they were not as interested in treating mental illness because it was not part of their professional identity.

I went into internal medicine because I like the internal medicine diseases and I like the whole idea of a differential diagnosis and sitting down with someone with a list of symptoms and … puzzling through what can be wrong with them and what can fix them. And the whole psych component of what I do … I spend a little bit of time pushing back against ‘cause it's not really what I want to do. (I-3)

In summary, providers expressed a lack of confidence in both the medical knowledge and experience involved in treating mental illness. Some felt that improved communication skills would help more than increased knowledge. They had varying attitudes about treating mental illness and whether they wanted further training in this area. Further, physicians discussed the challenges of maintaining their professionalism when interacting with specific patients, particularly those with challenging communication styles.

Healthcare System Factors

Physicians’ frustration with their lack of confidence in managing mental illness was accentuated by the clinical setting and overall healthcare system in which they worked. Physicians felt the clinical contexts in which they practiced negatively influenced their ability to care for these patients, specifically with: 1) lack of mental health resources 2) the separation of mental and physical health care, 3) clinic procedures, and 4) the US healthcare system as a whole.

Physicians at all clinical sites discussed barriers accessing mental health specialty care for their patients both with and without insurance. Providers also discussed the challenge of negotiating the complex payment systems in which mental health care is contracted to separate systems from medical health care.

[M]y patients who have the most psychosocial mental health complexity issues, a lot of them don't have the wherewithal to be able to handle everything once they leave. … If they don't have the wherewithal to take care of themselves, how are they going to have the wherewithal to make the phone call to take care of themselves? (I-2)

When consultation was available within their healthcare system, participants described difficulties in communicating with mental health specialists who often practiced in clinical settings separated from primary care by clinical location and electronic medical record system. Further, they described that patients often had to see mental health specialists in separate healthcare systems.

Many physicians stated that they would be able to manage complex patients more successfully if their clinics were restructured. For example, they felt that longer office visits would allow them to work through some of their communication challenges and manage the increased needs of complex patients.

I think it is the fact that I have 20 minute appointments for every patient. [T]here … is no ability to have more time with individual patients. (I-8)

Only two of the providers described having existing mental health resources in their clinics. Almost all providers identified additional support from mental health specialists in their clinics as the primary change that could improve care for their patients. They did not feel that increased coordination with mental health specialist off-site would be as beneficial.

So co-location of mental health in primary care is clearly the answer. That would allow me … not to have to communicate through some HIPPA secure portal to a provider in another location … I could just walk down the hall and talk to somebody … (I-10)

Physicians largely expressed dismay over the lack of resources for mental health in general and pessimism regarding the likelihood of receiving necessary support in the context of larger structural issues.

And I am talking about the system globally … access to care for mental health is different than our access to care for medical health. It's just preposterous. And it is really frustrating, because it really affects a lot of people. (I-8)

A minority of participants expressed a level of acceptance of the current healthcare system with inadequate resources for mental health. Physicians with this perspective recognized the need for primary care physicians to learn to address the needs of their patients with mental illness.

Mental health: I think we are going to have to figure out how to take care of it within … the primary care part of the medical system … And we are really doing it by default already … Just with a lot of resistance and not a lot of confidence … (I-15)

In summary, physicians felt that treatment for patients with co-morbid mental and medical illness was adversely affected by poor access to mental health specialty care and a lack of ancillary support in clinics and procedures that limited time with patients. Physicians conceived of these local issues as the result of problems with the larger healthcare system in the US.

DISCUSSION

In this study we sought internal medicine physician experiences of clinical complexity in their patients with co-occurring medical and mental illness. Participants were in broad agreement regarding patient characteristics, weaknesses in their own competency, and system issues that contributed to complexity but differed in their attitudes toward treating mental illness. Provider reactions to different patient communication styles, lack of communication training for physicians, and clinical contexts that did not support effective communication contributed to the challenge of caring for complex patients. Physicians expressed a desire for greater onsite mental health support. However, their opinions split on whether internal medicine physicians should be trained to treat mental illness.

This study is the first study, to our knowledge, to use qualitative methods to examine physician experiences treating complex patients with co-occurring mental and physical illness. Previous studies have elucidated the role of patient attachment style31 and physician characteristics32 in the patient-physician relationship. Our study contributes to an understanding of how the fragmentation of care, emphasized in the Institute of Medicine report Crossing theQuality Chasm,33 puts further strains on the patient-provider relationship. By asking physicians to bring and discuss patient notes, we were able to elicit unique observations on the role of the clinical context in communication challenges they face in their interactions with complex patients. Physicians expressed a sense of helplessness in trying to manage these interactions with very little training in communication skills and in the context of limited resources and time. Further, participants repeatedly described difficulties arising from fragmentation of care. They described great difficulty accessing medical records and discussing worrisome symptoms, such as suicidal ideation, because patients often had to seek specialty care for mental illness from providers in separate institutions. A strong sense of both isolation and frustration for physicians in trying to navigate this cumbersome system clearly emerged from the interviews.

Physician perceptions that mental illness increased the complexity of patient care in their patients with medical illness were not surprising given the many studies pointing to higher mortality rates, poorer clinical outcomes, and higher medical costs for medical illnesses in patients with co-occurring mental illness.4,6–8,34–37 Physicians in a qualitative study on multimorbidity in Britain briefly discussed the interaction between chronic mental and medical conditions.19 However, by specifically examining experiences with patients with mental and physical illnesses, we were able to clarify which aspects of care for mental illness these internists found most difficult. Physicians pointed to the acuity of the mental illness or the presence of active symptoms as important factors complicating their ability to treat medical illness. In a qualitative study of Norwegian General Practitioners’ experiences treating psychotic patients, physicians discussed difficulty in diagnosing the cause of the psychotic symptoms and initiating treatment for these patients, while they expressed satisfaction in providing care for patients with stable schizophrenia.20

Given the lack of psychiatry in internal medicine core curriculum, physicians’ perceived lack of both knowledge and skill in treating mental illness does not seem remarkable. American accreditation organizations currently do not require internal medicine training programs to include education in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.38,39 Nevertheless, physicians expressed a high level of comfort diagnosing and treating most patients with anxiety and depression. Their feelings of incompetency related primarily to patients with resistant anxiety and depression and serious mental illness; particularly bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. In a qualitative study of Brazilian primary care physicians, participants in focus groups also expressed more comfort with treating depression as opposed to more serious mental illness such as psychosis. Like physicians in our study, they discussed learning theory in medical school but lacking needed experiential skills in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.21

Although many physicians felt they were often required to practice outside of their scope of practice when treating complex patients with mental illness, they had differing opinions on whether they wanted increased training in this area. Some physicians preferred to focus on medical illness only, while others expressed a desire for further training to gain clinical competence in this area. Still others expressed a pragmatic attitude that general internists need to learn to treat mental illness due to the limited resources for specialty care. This practical approach is consistent with the current situation in the US, as many patients receive treatment for mental illness in primary care.13–16 Further, many patients prefer to receive treatment for mental illness in primary care. A large telephone survey in 2000, reported that the majority of patients, especially elderly patients, prefer treatment for mental illness in the primary care setting.40 Even though many internists may not wish to treat mental illness, some patients’ preferences for mental illness care in the primary care setting highlights the importance of clinical competency in this area of medicine.

Primary care physicians expressed great concern regarding limited access to specialty mental health care and difficulty negotiating the separate mental and medical health care systems. This distress was also noted in a qualitative study of Norwegian primary care physicians who reported frustration with limited mental health resources after-hours.41 The lack of integration of mental and medical health care both financially and structurally has been implicated as a factor in the poor health outcomes and increased costs of care in complex patients with co-occurring illness.42,43 For this reason, the Institute of Medicine has recommended increased integration of services as fundamental to improving the quality of care for patients with co-occurring mental and medical illness.44 Interestingly, providers in this study felt that co-location of specialty mental health providers would be more effective than increased coordination of care or access to consultation with off-site mental health specialists. However, collaborative care approaches which often use off-site psychiatry consultation, have proven effective in improving care for both depression and diabetes in primary care practices.45,46

The primary limitation of the study is its potentially limited generalizability, as all of the physicians were affiliated with a university in the Rocky Mountain region. Further the providers in this study were relatively young and most had been in practice for less than 10 years. Physicians working in smaller, private clinical settings might have patient populations with greater access to mental health care. Physicians in practice longer may develop greater skills for managing complex patient. However, the participants in this study worked in diverse settings including an academic medical center and urban, community health centers. These clinical sites were considered ideal for this study as they serve complex patient populations.

CONCLUSION

In this study of the management of complex patients with co-occurring mental and medical l illness, general internists pointed to specific patient characteristics, lack of training, and inadequate system resources for mental health care as factors that complicated the care of these patients. Since patient characteristics are relatively fixed, improvements in the quality of care should focus on improvements in physician training and in the systematic delivery of mental health care for complex patients. Increased integration of care offers one means of improving both physician training and the delivery of care for complex patients with mental illness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the University of Colorado Division of General Internal Medicine Small Grants program. Danielle Loeb, MD received salary support through the University of Colorado Primary Care Research Fellowship funded by Health Resources and Services Administration. Ingrid Binswanger, MD, MPH was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars Program, by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1R03DA029448, 1R21DA031041-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funders.

Prior Presentations

The findings from this study were presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Phoenix, AZ in 2011.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Appendix. Examples of Open-Ended Questions Regarding the Treatment of Mental Illness Used During Interviews

Working definition of complexity: A complex patient is defined as a person with two or more chronic conditions where each condition may influence the care of the other condition. This patient may have other factors such as age, race, gender and psychosocial issues that also influence the morbidity associated with their chronic conditions.

I would now like you to consider the interaction of mental illness and chronic medical illness in patients. Could you share with me your general impression of this interaction?

We are specifically interested in exploring the ways in which mental illness affects your management of medical illness. Could you share with me your impression of the impact of a mental illness in patients that are medically complex? Could you share with me any specific experiences you have had managing medically complex patients with mental illness?

Please refer to the patient charts you brought with you today. What made you pick these three charts?

If they have a mental illness diagnosis, can you talk a bit about whether their mental illness affects their care? Do you feel their mental illness affects their medical illnesses?

What do you find most enjoyable/rewarding in the care of these patients?

What do you find most frustrating / challenging in the care of these patients?

How have you been trained to care for patients with mental illness? Was there a specific activity in medical school or residency where you learned to treat patients with mental illness?) Were there specific training experiences after residency?

Is there any training that you feel would have better prepared you to treat complex patients, especially those with mental illness diagnoses?

What do you feel like you would need to improve your care of the complex patients in your clinic?

Is there anything on a system level in you clinic or beyond your clinic that would support you in the care of complex patients?

REFERENCES

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Program Brief. Mental Health: Research Findings http://www.ahrq.gov/research/mentalhth.htm. Accessed January 18, 2012.

- 2.Ani C, Bazargan M, Hindman D, et al. Depression symptomatology and diagnosis: discordance between patients and physicians in primary care settings. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egede LE, Nietert PJ, Zheng D. Depression and all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality among adults with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(6):1339–1345. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katon W, Fan MY, Unutzer J, Taylor J, Pincus H, Schoenbaum M. Depression and diabetes: a potentially lethal combination. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1571–1575. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0731-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental disorders and medical comorbidity. Synth Proj Res Synth Rep. 2011;21:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connerney I, Sloan RP, Shapiro PA, Bagiella E, Seckman C. Depression Is Associated With Increased Mortality 10 Years After Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(9):874–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hamer M, Batty GD, Stamatakis E, Kivimaki M. The combined influence of hypertension and common mental disorder on all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. J Hypertens. 2010;28(12):2401–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):802–813. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146332.53619.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kane GC, Grever MR, Kennedy JI, et al. The anticipated physician shortage: meeting the nation's need for physician services. Am J Med. 2009;122(12):1156–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreyenbuhl J, Dickerson FB, Medoff DR, et al. Extent and management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes and serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(6):404–410. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000221177.51089.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):357–363. doi: 10.1370/afm.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safford MM, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI. Patient complexity: more than comorbidity. the vector model of complexity. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):382–390. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mental disorders in general medical practice an opportunity to add value to healthcare. Behav HealthcTomorrow. Oct 1996;5(5):55-62, 72. [PubMed]

- 15.Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14(4):237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National patterns in antidepressant treatment by psychiatrists and general medical providers: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. J Clin Psychiatr. 2008;69(7):1064–1074. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirsti M. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bower P, Macdonald W, Harkness E, et al. Multimorbidity, service organization and clinical decision making in primary care: a qualitative study. Family practice. May 25 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Oud MJ, Schuling J, Slooff CJ. Meyboom-de Jong B. How do General Practitioners experience providing care for their psychotic patients? BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballester DA, Filippon AP, Braga C, Andreoli SB. The general practitioner and mental health problems: challenges and strategies for medical education. Sao Paulo Med J. 2005;123(2):72–76. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802005000200008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mays N, Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ. 1995;311(6997):109–112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickinson LM, Dickinson WP, Rost K, et al. Clinician burden and depression treatment: disentangling patient- and clinician-level effects of medical comorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1763–1769. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0738-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Evaluation. 2006;27:237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton MQ. Qualitative EvaluationMethods. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patton M. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan B.Analyzing QualitativeData. Systemic Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010.

- 29.Miles MB, Huberman AM.Qualitative dataanalysis : an expandedsourcebook. Thousand Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage; 1994.

- 30.Medical professionalism in the new millennium A physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–246. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciechanowski P, Katon WJ. The interpersonal experience of health care through the eyes of patients with diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(12):3067–3079. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krebs EE, Garrett JM, Konrad TR. The difficult doctor? Characteristics of physicians who report frustration with patients: an analysis of survey data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:128. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing theQuality Chasm: A NewHealth Systemfor the21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- 34.Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18–24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1117-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cynthia Boyd BL, Carols Weiss, Jennifer Wolff, and Lorie Martin.Clarifying MultimorbidityPatterns toImprove Targetingand Deliveryof ClinicalServices forMedicaid Populations: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc.; December 2010.

- 36.Lin EH, Heckbert SR, Rutter CM, et al. Depression and increased mortality in diabetes: unexpected causes of death. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(5):414–421. doi: 10.1370/afm.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas MR, Waxmonsky JA, Gabow PA, Flanders-McGinnis G, Socherman R, Rost K. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and costs of care among adult enrollees in a Medicaid HMO. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(11):1394–1401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.11.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Resident Education In Internal Medicine. 2009; http://www.acgme.org/acwebsite/rrc_140/140_prindex.asp. Accessed January 18, 2012.

- 39.American Board of Internal Medicine. Internal Medicine Policies. 2011; http://www.abim.org/certification/policies/imss/im.aspx. Accessed January 18, 2012.

- 40.Mickus M, Colenda CC, Hogan AJ. Knowledge of mental health benefits and preferences for type of mental health providers among the general public. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2):199–202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johansen IH, Carlsen B, Hunskaar S. Psychiatry out-of-hours: a focus group study of GPs' experiences in Norwegian casualty clinics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:132. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kilbourne AM, Fullerton C, Dausey D, Pincus HA, Hermann RC. A framework for measuring quality and promoting accountability across silos: the case of mental disorders and co-occurring conditions. Qual Health Care. 2010;19(2):113–116. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.027706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, Pincus HA. From silos to bridges: meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. Health Aff. 2006;25(3):659–669. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving theQuality ofHealth Carefor Mentaland Substance-Use Conditions. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2006.

- 45.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katon WJ, Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]