Abstract

Preeclampsia is a common complication of pregnancy associated with high maternal morbidity and mortality and intrauterine fetal growth restriction. There is extensive evidence that the reduction of uteroplacental blood flow in this syndrome results from the toxic combination of hypoxia, imbalance of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors, inflammation, and deranged immunity. Women treated for preeclampsia also have an increased risk for cardiovascular and renal disease. At present it is unclear if the increased cardiovascular and renal disease risks are due to residual and or progressive effects of endothelial damage from the preeclampsia or from shared risk factors between preeclampsia and cardiac disease. Moreover, it appears that endothelin-1 signaling may play a central role in the hypertension associated with preeclampsia. In this paper, we discuss emerging data on the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and review therapeutic options.

1. Introduction

Preeclampsia, a human-pregnancy-specific disease defined as the occurrence of hypertension and significant proteinuria in a previously healthy woman on or after the 20th week of gestation, occurs in about 2–8% of pregnancies [1, 2]. It is the most common medical complication of pregnancy whose incidence has continued to increase worldwide, and It is associated with significant maternal morbidity and mortality, accounting for about 50,000 deaths worldwide annually [3, 4]. Thus reducing maternal mortality by 75% between 1990 and 2015 has been considered as part of the millennium development goals of the World Health Organization (WHO) Nations [5]. Risk factors for preeclampsia include nulliparity, multifetal gestations, previous history of preeclampsia, obesity, diabetes mellitus, vascular and connective tissue disorders like systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid antibodies, age >35 years at first pregnancy, smoking, and African American race. Among primiparous women, there is a disparity among ethnic groups as the risk in African American women is twice that of Caucasian women, and the risk is also very high in women of Indian and Pakistani origin [6]. The connection between these risk factors and preeclampsia is poorly understood. The differences in risk among ethnic groups suggest a strong role for genetic factors in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Most theories on the etiology of preeclampsia suggest that the disease is a cascade triggered by combination of abnormal maternal inflammatory response, endothelial cell activation/damage with deranged hemodynamic milieu, and deranged immunity [7–12]. The precise trigger that unifies the deranged vascular, immune and inflammatory responses remains to be elucidated. In this paper, we discuss emerging concepts in pathogenesis of preeclampsia and review therapeutic options.

2. Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia and Hemodynamic Changes

Preeclampsia is characterized by placental hypoxia and/or ischemia, excessive oxidative stress, in association with endothelial dysfunction. Release of soluble factors from the ischemic placenta into maternal plasma plays a central role in the ensuing endothelial dysfunction that is the most prominent feature of this disease. Recent data have suggested that endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia results from an antiangiogenic state mediated by high circulating levels of soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) and soluble endoglin in concert with low levels of proangiogenic factors like placental growth factor (PlGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The placenta makes sFlt1 in large amounts, but circulating mononuclear cells have also been shown be an extra source of sFlt1 in preeclampsia [9, 10]. High-circulating levels of sFlt1 have been documented in women with preeclampsia [13], and this high level may predate the onset of preeclampsia [12], and the severity of preeclampsia may correlate with the levels of sFlt1 [13]. Thus sFlt1 acts as a potent and inhibitor of VEGF and PIGF by binding these molecules in the circulation and other target tissues, such as, the kidneys. Consistent with these observations, administration of sFlt1 to pregnant rats produces a syndrome that mimics preeclampsia with hypertension, proteinuria, and edema [14], while anti-VEGF therapy in cancer patients has been shown to cause hypertension and proteinuria in cancer patients [15]. Thus the preponderance of evidence shows that excessive sFlt-1 plays a central role in induction of the preeclampsia phenotype as sFLt-1 decreases VEGF binding to its receptor which reduces phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) by VEGF an effect which culminates in reduced eNOS [16].

While it has been traditionally assumed that preeclampsia is a self-limited disease that resolves once the baby and placenta are delivered, some studies have shown that this maternal endothelial dysfunction can last for years after the episode of preeclampsia [17, 18]. A recent analysis actually confirmed that a history of preeclampsia is associated with a doubling of the risk for cardiac, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease compared to women without such a risk factor [19–22]. Furthermore, such women have also been shown to have increased risk for renal diseases, such as, Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and microalbuminuria. The children born after a pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia have also been shown to be at high risk for complications like diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension [23, 24]. The pathogenesis of this increased risk has not been defined, but suggested contributing factors include fetal malnutrition, epigenetic modification, and postnatal growth acceleration [25]. Furthermore, the endothelial dysfunction and other vascular perturbations observed in preeclampsia actually begin early in pregnancy, though the severe vascular outcomes become evident after 20 weeks of gestation which is an important issue that should be considered in designs of therapeutic and prevention interventions. This may even pose a challenge in the entire concept of diagnosing and treating this disorder as an issue that begins after the 20th week of pregnancy.

3. Evidence for Inflammation in Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia

Normal pregnancy induces changes in maternal physiology to accommodate the fetus and the placenta, as well as products from the fetoplacental unit, such as, placental exosomes, microparticles, and microchimeric cells. In normal pregnancy, there is a shift towards a Th2-type immune response which protects the baby from a Th1-type (cytotoxic) response which could harm the baby with its products like interleukin-2, IL-12, interferon γ (IFNY), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα). Thus inflammation appears to be the link between the adaptive immune response and the occurrence of preeclampsia. Systemic inflammation in preeclampsia appears to favor a preponderance of Th1-type reaction [26]. Redman et al. initially proposed that preeclampsia arises from an exaggerated maternal vascular inflammatory response [27]. Consistent with this observation, some studies show an abundance of soluble markers of neutrophil activation in preeclampsia [28–30], while others have demonstrated amplification of inflammation in preeclampsia by activation of the complement system [31]. Specifically, the cytokines TNF and interleukin 6 (IL-6) are elevated in preeclamptic women. However, the role of inflammation as the cause of preeclampsia is weakened by the failure of several studies to find a strong and consistent association between increase in inflammatory status and clinical signs of preeclampsia [32, 33]. Consistent with these observations, pregnant women with excessive inflammation and high cytokine levels, like those with severe infections, do not always develop preeclampsia.

4. A Unifying Hypothesis on Preeclampsia: Deranged Endothelin and Nitric Oxide Signaling

The placenta is the most central organ in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Except for postpartum cases, removal of the placenta abolishes the disease. Furthermore, the placenta, not the fetus is a sine qua non for the development of preeclampsia which can also occur in molar pregnancies. A major advance in the understanding of the pathogenesis of preeclampsia is the development of excellent animal models of this disease. Using these models, such as, the uterine perfusion reduction model [34], it has been shown that the occurrence of hypertension, proteinuria, and endothelial dysfunction was associated with raised sFLt1 and elevated preproendothelin levels. Furthermore, administration of endothelin type A receptor antagonist completely normalized the hypertension in this model, whereas this antagonist had no effect in normal pregnant controls [34]. In a second model where animals were administered excess amounts of sFLt1 to mimic preeclampsia, endothelin signaling was increased and coadministration of an endothelin antagonist abrogated this hypertensive response. This suggests that the hypertension associated with excess sFLt1 in preeclampsia is dependent on endothelin signaling [34]. Soluble endoglin (sEng) is another antiangiogenic factor isolated from the placenta and blood of women with preeclampsia. sEng inhibits the binding of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β to its receptor and causes down stream down regulation of nitric oxide synthase [35]. Thus the combination of raised sFlt1 and sEng appears to impair nitric oxide generation and activate endothelin-1 signaling with hypertension and aggravation of maternal endothelial dysfunction [36, 37]. Using knockout mice models, it has been shown that mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide (eNOS) have hypertension, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and decreased nitric oxide (NO) production [37–40]. Some, but not all studies, show that NOS3 polymorphisms leading to lower NO production are associated with hypertension [40] and/or preeclampsia. Finally, Li et al. have recently shown that lack of eNOS aggravates the preeclampsia phenotype induced by increased sFLt1 in nonpregnant female mice [41]. While these animal studies cannot be directly extrapolated to humans they illuminate possible mechanisms where endothelin transmission and changes in eNOS that affect endothelial function can contribute to the pathogenesis of this syndrome. Another humoral mediator whose role has been evaluated in preeclampsia is relaxine. Relaxine is a 6-kilodalton peptide hormone secreted by the corpus luteum and circulates in maternal blood during pregnancy. Its administration presence and/or administration during pregnancy leads to rapid and sustained vasodilation in the maternal circulation. Thus it would appear to be an important hormone to assess in a disease associated with vasoconstriction, such as, preeclampsia. The sustained maternal vasodilatory actions seen with relaxine appear to be critically dependent onvascular endothelial growth factors like gelatinases which in turn activates the endothelium (ET)B/nitric oxide vasodilatory pathway [42–44]. However, though relaxin is indeed significantly elevated in the serum of women in late pregnancy, serum relaxin levels have not been shown to influence blood pressure, renal vascular resistance, renal blood flow, or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in late pregnancy or in women with preeclampsia [45].

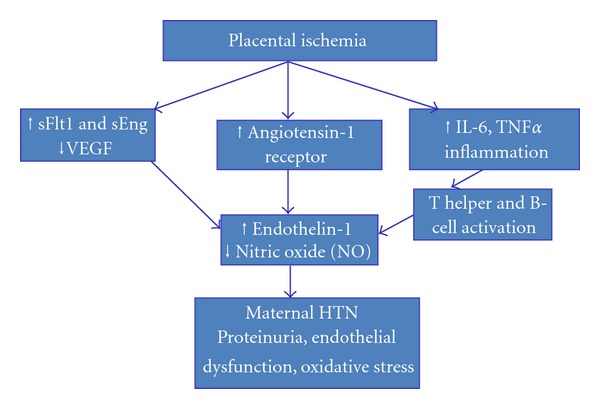

Figure 1 illustrates how placental ischemia activates the preeclampsia cascade and alters the balance between endothelin-1 and NO, resulting in the observed endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria.

Figure 1.

Showing unified hypothesis on pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and edema with preeclampsia.

5. The Kidney in Preeclampsia: New Concepts on Pathogenesis

The phenotypic effects of maternal endothelial damage have been best understood in the kidney, where glomerular endotheliosis, generalized swelling, and vacuolization of endothelial cells have been noted [46, 47]. It appears that VEGF plays a critical role in maintenance of normal glomerular endothelial integrity. Furthermore, in vitro angiogenesis studies have demonstrated that exogenous VEGF/PlGF or an antibody against sFlt-1 can reverse the antiangiogenic effects of preeclamptic plasma [44]. It has been shown that podocyte injury and reduced specific podocyte protein expressions contribute to proteinuria in preeclampsia. In a recent study, Wang et al. showed that urinary excretion of podocyte specific proteins, such as, podocalyxin, nephrin, and Big-h3 were significantly elevated in women with preeclampsia [48].

6. Therapies for Preeclampsia: Magnesium Sulfate, Aspirin, Calcium, Antioxidants, Endothelin Antagonists

Currently the main therapy for preeclampsia is to deliver the baby as soon as he/she is most prudent to enhance maternal and fetal wellbeing.

6.1. Magnesium Sulfate

This is the most effective agent in prevention of eclampsia in women with preeclampsia. It has antiseizure effects as well as a being a vasodilator. Studies have shown that magnesium sulfate decreases pulsatility index in uterine, umbilical, and fetal arteries in women with preeclampsia [48, 49]. However, the mechanism of seizure prevention in preeclampsia may be independent of changes in angiogenic factors, as one study did not find alteration in angiogenic factor levels in preeclamptic women given magnesium sulfate, compared to placebo controls [50]. Magnesium sulfate also normalizes placental interlekin-6 secretion in a model of preeclampsia [51], which supports the fact that some of its benefits may drive from anti-inflammatory actions.

6.2. Aspirin

Since inflammation appears to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, some investigators have studied the role of aspirin in prevention and therapy of preeclampsia. While some small single-center studies suggest a benefit for aspirin in preeclampsia [52, 53], larger multicenter trials have shown little or no effect [54, 55]. Possible explanations for the lack of reproducibility of benefits in larger studies include heterogeneity of preeclampsia, with benefit of therapy evident only in small subsets, as well as possible publication bias in favor of positive results in small studies. Dudley et al. performed a meta-analysis which has suggested a possible benefit of antiplatelet agents in preeclampsia. A large meta-analysis showed that aspirin use reduced the incidence of preeclampsia by 17%, and a 14% reduction in fetal and neonatal deaths, with 72 women needing treatment to benefit one woman [56, 57]. It is possible that benefits from aspirin in prevention of preeclampsia and its vascular complication may derive not just from an anti-inflammatory action but from a putative effect of restoring the balance between thromboxane and prostacyclin in the vasculature. Before using aspirin to prevent preeclampsia, consideration must be given to the toxicity in the gastrointestinal tract and effects on renal function [58].

6.3. Calcium

Calcium supplementation has been suggested by some to have modest benefits in prevention of preeclampsia [59]. However, a large, randomized trial by Levine failed to find any benefit of supplemental calcium (2 gm daily) given to women in early pregnancy in prevention of preeclampsia [60]. Another randomized, controlled trial by the WHO showed that while calcium supplementation did not reduce the incidence of preeclampsia, it appeared to reduce adverse outcomes in women who developed preeclampsia [59]. Consequently, calcium supplementation has been recommended in populations with a low calcium intake [61].

6.4. Antioxidants

In response to data suggesting that increased oxidative stress and derangement of antioxidative mechanisms occur in preeclampsia [62], some have advocated use of antioxidants in treatment of preeclampsia. As with aspirin and calcium, small studies suggested a benefit, but the largest study to date done by Roberts et al showed no benefit [63]. With regards to Vitamin A and E, one study showed low levels in diabetics with preeclampsia [64], while another study showed low levels of vitamin A and E in preeclamptic women in northern Nigeria [65]. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial of vitamin C and E supplementation in early pregnancy in high-risk women by the World Health Organization (WHO) did not prevent preeclampsia [66]. Consistent with these observations, a recent systematic review of antioxidant administration in early pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia found no benefit [67].

6.5. Endothelin Antagonists

Since endothelin nitric oxide appears to act through endothelin to aggravate sFLt1-induced preeclampsia-like phenotype, some investigators have studied the benefits of endothelin antagonism in treatment of preeclampsia. Antagonism of endothelial-A receptor has proved beneficial in some animal models of preeclampsia. In one model, administration of ambrisentan, an endothelin antagonist, was shown to improve creatinine clearance and podocyte effacement in ENOS-deficient mice sFlt1 mice [68]. Treatment with Ambrisentan also decreased proteinuria and ameliorates the endotheliosis classically seen in the kidneys of preeclamptic animals [69]. However, use of endothelin antagonists in early human pregnancy has not been tried as they have also been shown to induce birth defects in some studies [70]. It is possible that these agents may have a better safety profile if used in late pregnancy, but more studies would be needed to establish their safety in this setting. The goal remains to find therapeutic and preventive measures that can reduce maternal and fetal mortality from preeclampsia [71].

6.6. Use of Nitric Oxide Donors

Since preeclampsia is associated with reduced synthesis of vasodilators and increased synthesis of vasoconstrictors, researchers have sought to investigate possible therapeutic benefit for use of NO donors in treatment and prevention of preeclampsia. Animal data have shown that chronic nitric oxide blockade is associated with hypertension, proteinuria, and reductions in kidney function [72, 73]. Consistent with these observations, use of nitric oxide donors has shown benefit in a few human studies [74–77]. In one case a successful pregnancy followed use of nitric oxide donors in a patient with scleroderma who had had preeclampsia in a preceding pregnancy [77]. However, until this is validated in large scale, prospective randomized studies use of these nitric oxide donors cannot be recommended in all patients. They should be considered in selected patients, such as, those with scleroderma [78].

7. Unresolved Issues in Pathogenesis

7.1. Postpartum Preeclampsia/Eclampsia and the Antiangiogenic Theory

Postpartum preeclampsia (occurrence of hypertension and proteinuria) or postpartum eclampsia (occurrence of hypertension, proteinuria, and seizures) after delivery challenges the concept of the primacy of placental ischemia as the critical determinant of the occurrence of this syndrome. In this situation, the placenta has been removed, thus eliminating the source of the antiangiogenic factors that creates the milieu that helps trigger the vascular cascade. While postpartum eclampsia may occur from progression of preeclampsia, it may rarely occur without preceding preeclampsia and posing a diagnostic challenge [79]. Larsen has described factors that increase the risk for postpartum preeclampsia, such as, a body mass index (BMI) > 30, antenatal hypertensive disease, cesarean delivery, and African American race [78]. More education of providers and patients may help prevent late postpartum eclampsia [79].

7.2. Role of Thromboxane Synthase

Since 1985, it has been known that abnormal hemostasis and coagulopathy occur in preeclampsia and eclampsia [80]. This appeared to be related to an imbalance between an increased vasoconstrictor (thromboxane) and a decreased vasodilator (prostacyclin) in maternal blood [81]. Consistent with these observations, an increase in thromboxane synthase has been observed in decidua and trophoblast cells of placenta of women with preeclampsia. Recently some investigators have shown that reduced methylation of thromboxane synthase gene is correlated with its increase of vascular expression in preeclampsia [82]. How this altered thromboxane synthase gene expression plays into the deranged antiangiogenic milieu remains to be established. One putative link could be that reduced DNA methylation may increase thromboxane synthase in in neutrophils that infiltrate maternal blood vessels triggering inflammation in vascular smooth muscle and endothelium. This culminates in endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and edema.

8. Conclusion

An accumulating body of evidence is helping to elucidate the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, showing the intricate link between placental and vascular ischemia, impaired angiogenesis, vascular inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. If perturbed endotheil-1 signaling and/or disruption of endothelin-1/NO balance are proven to be the final common pathway for induction of preeclampsia, this concept would have huge translational potential implications. Translational studies are now needed to show how this emerging concepts can be applied to facilitate early diagnosis and therapy.

References

- 1.Ghulmiyyah L, Sibai B. Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/eclampsia. Seminars in Perinatology. 2012;36(1):56–59. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moodley J. Maternal deaths associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a population-based study. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2004;23(3):247–256. doi: 10.1081/PRG-200030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duley L. The global impact of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Seminars in Perinatology. 2009;33(3):130–137. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Preeclampsia and Eclampsia. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Department of Maternal and Child Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osungbade OK, Ige OK. Public heath perspectives of preeclampsia in developing countries: implication for health system strenghtening. Journal of Pregnancy. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/481095.481095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao AK, Daniels K, El-Sayed YY, Moshesh MK, Caughey AB. Perinatal outcomes among Asian American and Pacific Islander women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;195(3):834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg G, Khankin EV, Karumanchi SA. Angiogenic factors and preeclampsia. Thrombosis Research. 2009;123:S93–S99. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal PK, Chandel N, Jain V, Jha V. The relationship between circulating endothelin-1, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and soluble endoglin in preeclampsia. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2011;26:236–241. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui D, Okun N, Murphy K, Kingdom J, Uleryk E, Shah PS. Combinations of maternal serum markers to predict preeclampsia, small for gestational age, and stillbirth: a systematic review. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2012;34(2):142–153. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35157-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nature Medicine. 2006;12(6):642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramma W, Ahmed A. Is inflammation the cause of pre-eclampsia? Biochemical Society Transactions. 2011;39(6):1619–1627. doi: 10.1042/BST20110672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clifton VL, Stark MJ, Osei-Kumah A, Hodyl NA. Review: the feto-placental unit, pregnancy pathology and impact on long term maternal health. Placenta. 2012;33:S37–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powe CE, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia, a disease of the maternal endothelium: the role of antiangiogenic factors and implications for later cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;123(24):2856–2869. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.853127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(10):992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izzedine H, Massard C, Spano JP, Goldwasser F, Khayat D, Soria JC. VEGF signalling inhibition-induced proteinuria: mechanisms, significance and management. European Journal of Cancer. 2010;46(2):439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gélinas DS, Bernatchez PN, Rollin S, Bazan NG, Sirois MG. Immediate and delayed VEGF-mediated NO synthesis in endothelial cells: role of PI3K, PKC and PLC pathways. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;137(7):1021–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. American Heart Journal. 2008;156(5):918–930. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith GCS, Pell JP, Walsh D. Pregnancy complications and maternal risk of ischaemic heart disease: a retrospective cohort study of 129 290 births. The Lancet. 2001;357(9273):2002–2006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vikse BE, Irgens LM, Leivestad T, Skjærven R, Iversen BM. Preeclampsia and the risk of end-stage renal disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(8):800–809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald SD, Han Z, Walsh MW, Gerstein HC, Devereaux PJ. Kidney disease after preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2010;55(6):1026–1039. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2007;335(7627):974–977. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): population-based retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1797–1803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawlor DA, MacDonald-Wallis C, Fraser A, et al. Cardiovascular biomarkers and vascular function during childhood in the offspring of mothers with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. European Heart Journal. 2012;33(3):335–345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palti H, Rothschild E. Blood pressure and growth at 6 years of age among offsprings of mothers with hypertension of pregnancy. Early Human Development. 1989;19(4):263–269. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(89)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams D . Long-term complications of preeclampsia. Seminars in Nephrology. 2011;31(1):111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunology Today. 1993;14(7):353–356. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redman CWG, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180(2 I):499–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shamshirsaz AA, Paidas M, Krikun G. Preeclampsia, hypoxia, and inflammation. Journal of Pregnancy. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/374047.374047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szarka A, Rigó J, Lázár L, Beko G, Molvarec A. Circulating cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia determined by multiplex suspension array. BMC Immunology. 2010;11, article 59 doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma A, Satyam A, Sharma JB. Leptin, IL-10 and inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8) in pre-eclamptic, normotensive pregnant and healthy non-pregnant women. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2007;58(1):21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynch AM, Murphy JR, Gibbs RS, et al. The interrelationship of complement-activation fragments and angiogenesis-related factors in early pregnancy and their association with pre-eclampsia. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2010;117(4):456–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Djurovic S, Clausen T, Wergeland R, Brosstad F, Berg K, Henriksen T. Absence of enhanced systemic inflammatory response at 18 weeks of gestation in women with subsequent pre-eclampsia. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(7):759–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kronborg CS, Gjedsted J, Vittinghus E, Hansen TK, Allen J, Knudsen UB. Longitudinal measurement of cytokines in pre-eclamptic and normotensive pregnancies. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2011;90(7):791–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.George EM, Granger JP. Endothelin: key mediator of hypertension in preeclampsia. American Journal of Hypertension. 2011;24:964–969. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Q, Chen L, Liu B, et al. The role of autocrine TGFβ1 in endothelial cell activation induced by phagocytosis of necrotic trophoblasts: a possible role in the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. Journal of Pathology. 2010;221(1):87–95. doi: 10.1002/path.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandrim VC, Palei ACT, Metzger IF, Gomes VA, Cavalli RC, Tanus-Santos JE. Nitric oxide formation is inversely related to serum levels of antiangiogenic factors soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and soluble endogline in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;52(2):402–407. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.115006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duplain H, Burcelin Ŕ, Sartori C, et al. Insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2001;104(3):342–345. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niu W, Qi Y. An updated meta-analysis of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene: three well-characterized polymorphisms with hypertension. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024266.e24266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serrano NC, Casas JP, Díaz LA, et al. Endothelial NO synthase genotype and risk of preeclampsia: a multicenter case-control study. Hypertension. 2004;44(5):702–707. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143483.66701.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fatini C, Sticchi E, Gensini F, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene influences the risk of pre-eclampsia, the recurrence of negative pregnancy events, and the maternal-fetal flow. Journal of Hypertension. 2006;24(9):1823–1829. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000242407.58159.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li F, Hagaman JR, Kim H-S, et al. eNOS deficiency acts through endothelin to aggravate sFlt-1-induced pre-eclampsia-like phenotype. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012;23(4):652–660. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conrad KP. Maternal vasodilation in pregnancy: the emerging role of relaxin. American Journal of Physiology. 2011;301(2):R267–R275. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00156.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conrad KP. Emerging role of relaxine in the maternal adaptation to normal pregnancy:implications for preeclampsia. Seminars in Nephrology. 2011;31(1):15–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unemori E, Sibai B, Teichmana SL. Scientific rationale and design of a phase I safety study of relaxin inwomen with severe preeclampsia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1160:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lafayette RA, Hladunewich MA, Derby G, Blouch K, Druzin ML, Myers BD. Serum relaxin levels and kidney function in late pregnancy with or without preeclampsia. Clinical Nephrology. 2011;75(3):226–232. doi: 10.5414/cnp75226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005;308(5728):1592–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.1111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stillman IE, Karumanchi SA. The glomerular injury of preeclampsia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;18(8):2281–2284. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Zhao S, Loyd S, Groome LJ. Increased urinary excretion of nephrin, podocalyxin, and βig-h3 in women with preeclampsia. American Journal of Physiology. 2012;302(9):F1084–F1089. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00597.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dasgupta S, Ghosh D, Seal SL, Kamilya G, Karmakar M, Saha D. Randomized controlled study comparing effect of magnesium sulfate with placebo on fetal umbilical artery and middle cerebral artery blood flow in mild preeclampsia at ≥34 weeks gestational age. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2012;38(5):763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Souza ASR, Amorim MMR, Santos RE, Neto CN, Porto AMF. Effect of magnesium sulfate on pulsatility index of uterine, umbilical and fetal middle cerebral arteries according to the persistence of bilateral diastolic notch of uterine arteries in patients with severe preeclampsia. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 2009;31(2):82–88. doi: 10.1590/s0100-72032009000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vadnais MA, Rana S, Quant HS, et al. The impact of magnesium sulfate therapy on angiogenic factors in preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertension. 2012;2(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2011.08.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.la Marca B, Brewer J, Wallace K. IL-6-induced pathophysiology during pre-eclampsia: potential therapeutic role for magnesium sulfate? International Journal of Interferon, Cytokine and Mediator Research. 2011;3(1):59–64. doi: 10.2147/IJICMR.S16320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beaufils M, Donsimoni R, Uzan S, Colau JC. Prevention of pre-elcampsia by early antiplatelet therapy. The Lancet. 1985;1(8433):840–842. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiff E, Peleg E, Goldenberg M, et al. The use of aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321(6):351–356. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908103210603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL, Parker R, et al. Low-dose aspirin therapy to prevent preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;168(4):1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90351-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beroyz G, Casale R, Farreiros A, et al. CLASP: a randomised trial of low-dose aspirin for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia among 9364 pregnant women. The Lancet. 1994;343(8898):619–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(11):701–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberts JM, Catov JM. Aspirin for pre-eclampsia: compelling data on benefit and risk. The Lancet. 2007;369(9575):1765–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Askie LM, Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Stewart LA. Antiplatelet agents for prevention of pre-eclampsia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. The Lancet. 2007;369(9575):1791–1798. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verheugt FWA, Bolte AC. The role of aspirin in women's health. International Journal of Women's Health. 2011;3(1):151–166. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S18033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Cook RJ, et al. Effect of calcium supplementation on pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia: a peta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(14):1113–1117. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530380055031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mert I, Oruc AS, Yuksel S, et al. Role of oxidative stress in preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2012;38(4):658–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roberts JM, Myatt L, Spong Y, et al. Vitamins C and E to prevent complications of pregnancy-associated hypertension. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(14):1282–1291. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kassab S, Miller MT, Hester R, Novak J, Granger JP. Systemic hemodynamics and regional blood flow during chronic nitric oxide synthesis inhibition in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 1998;31(1):315–320. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sladek SM, Magness RR, Conrad KP. Nitric oxide and pregnancy. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272(2):R441–R463. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rytlewski K, Olszanecki R, Korbut R, Zdebski Z. Effects of prolonged oral supplementation with L-arginine on blood pressure and nitric oxide synthesis in preeclampsia. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;35(1):32–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Begum S, Yamasaki M, Mochizuki M. Urinary levels of nitric oxide metabolites in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 1996;22(6):551–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1996.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roberts JM, Davidge ST, Silver RK, Caplan MS. Plasma nitrites as an indicator of nitric oxide production: unchanged production or reduced renal clearance in preeclampsia? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;176(4):954–955. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70639-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carbonne B, Macé G, Cynober E, Milliez J, Cabane J. Successful pregnancy with the use of nitric oxide donors and heparin after recurrent severe preeclampsia in a woman with scleroderma. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(2):e6–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Giuggioli D, Colaci M, Sebastiani M, Ferri C. L-arginine in pregnant scleroderma patients. Clinical Rheumatology. 2010;29(8):937–939. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mistry HD, Williams PJ. The importance of antioxidant micronutrients in pregnancy. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2011;2011:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/841749.841749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rossi AC, Mullin PM. Prevention of pre-eclampsia with low-dose aspirin or vitamins C and E in women at high or low risk: a systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2011;158(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Villar J, Purwar M, Merialdi M, et al. World Health Organisation multicentre randomised trial of supplementation with vitamins C and e among pregnant women at high risk for pre-eclampsia in populations of low nutritional status from developing countries. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2009;116(6):780–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salles AMR, Galvao TF, Silva MT, Motta LCD, Pereira MG. Antioxidants for preventing preeclampsia: a systematic review. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:10 pages. doi: 10.1100/2012/243476.243476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Treinen KA, Louden C, Dennis MJ, Wier PJ. Developemental toxicity and toxicokinetics of 2 endothelial antagonists in rats and rabbits. Terratology. 1999;59(1):51–59. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199901)59:1<51::AID-TERA10>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Clark SL, Hankins GDV. Preventing maternal death: 10 clinical diamonds. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;119(2):360–364. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182411907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chhabra S, Tyagi S, Bhavani M, Gosawi M. Late postpartum eclampsia. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012;32(3):264–266. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.639467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larsen WI, Strong JE, Farley JH. Risk factors for late postpartum preeclampsia. Journal of Reproductive Medicine for the Obstetrician and Gynecologist. 2012;57(1):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chames MC, Livingston JC, Ivester TS, Barton JR, Sibai BM. Late postpartum eclampsia: a preventable disease? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;186(6):1174–1177. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Walsh SW. Preeclampsia: an imbalance in placental prostacyclin and thromboxane production. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985;152(3):335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(85)80223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chavarría ME, Lara-González L, González-Gleason A, García-Paleta Y, Vital-Reyes VS, Reyes A. Prostacyclin/thromboxane early changes in pregnancies that are complicated by preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(4):986–992. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mousa AA, Strauss III JF, Walsh SW. Reduced methylation of the thromboxane synthase gene is correlated with its increased vascular expression in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2012;59(6):1249–1255. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.188730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]