Abstract

AIMS

To evaluate the pharmacology and tolerability of PF-04457845, an orally available fatty acid amide hydrolase-1 (FAAH1) inhibitor, in healthy subjects.

METHODS

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled single and multiple rising dose studies and an open-label, randomized, food effect study were conducted. Plasma and urine PF-04457845 concentrations, plasma fatty acid amide concentrations and FAAH1 activity in human leucocytes were measured. Tolerability, including effects on cognitive function, were assessed.

RESULTS

PF-04457845 was rapidly absorbed (median tmax 0.5–1.2 h). Exposure increased supraproportionally to dose from 0.1 to 10 mg and proportionally between 10 and 40 mg single doses. The pharmacokinetics appeared dose proportional following 14 days once daily dosing between 0.5 and 8 mg. Steady-state was achieved by day 7. Less than 0.1% of the dose was excreted in urine. Food had no effect on PF-04457845 pharmacokinetics. FAAH1 activity was almost completely inhibited (>97%) following doses of at least 0.3 mg (single dose) and 0.5 mg once daily (multiple dose) PF-04457845. Mean fatty acid amide concentrations increased (3.5- to 10-fold) to a plateau and then were maintained following PF-04457845. FAAH1 activity and fatty acid amide concentrations returned to baseline within 2 weeks following cessation of dosing at doses up to 4 mg. There was no evidence of effects of PF-04457845 on cognitive function. PF-04457845, at doses up to 40 mg single dose and 8 mg once daily for 14 days, was well tolerated.

CONCLUSIONS

PF-04457845 was well tolerated at doses exceeding those required for maximal inhibition of FAAH1 activity and elevation of fatty acid amides.

Keywords: fatty acid amide hydrolase-1 (FAAH1), fatty acid amide, irreversible inhibitor, PF-04457845, pharmacokinetics

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase-1 (FAAH1) and the subsequent elevation of fatty acid amides has been proposed as a strategy to induce the analgesic properties of cannabinoids without the accompanying negative side effects such as impairment in cognition, motor control and predisposition to psychoses. PF-04457845 is a potent and selective irreversible FAAH1 inhibitor which has been shown to elevate fatty acid amide concentrations in animal models and induce responses in behavioural models suggestive of analgesia.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study is the first to investigate a FAAH1 inhibitor in humans. PF-04457845 is well tolerated following single and multiple dosing to healthy volunteers and has pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties that make nearly complete inhibition of FAAH1 possible with once daily dosing.

Introduction

A systematic review [1] of placebo-controlled, randomized controlled studies, including five in patients suffering from multiple sclerosis (MS), comparing either extracts of herbal cannabis or the major psychoactive constituent of cannabis, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, demonstrated significantly greater pain relief from the cannabinoid than placebo in the majority of the studies. However, these agents have also been reported to produce undesirable side effects including impairments in cognition, motor control and predisposition to psychosis, which limit their utility as therapeutic agents [2].

The integral membrane enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase-1 (FAAH1) catalyzes the degradation of several endogenous lipids believed to be neurotransmitters, including N-arachidonyl ethanolamine (anandamide, AEA), N-palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), N-oleoylethanolamide (OEA) and N-linoleoyl ethanolamine (LEA), which have biological effects via pathways including those initiated through cannabinoid (CB) receptors [3]. Inhibition of this enzyme has been proposed as a strategy by which the analgesic properties of cannabinoids may be preserved without the accompanying negative effects [4]. Behavioural studies comparing FAAH1 (-/-) mice compared with wild-type controls [5]–[7] indicated attenuated responses to painful stimuli without disruptions in motility (including catalepsy and reduced locomotor activity that is commonly associated with CB1 receptor agonist responses) or body temperature [5], [7], [8]. Conclusions from genetically modified mice are supported by the results from pharmacological manipulation of FAAH1 in rodents (see [9]–[13]).

PF-04457845 (N-pyridazin-3-yl-4-{3-[5-(trifluoromethyl)-2-pyridyloxy]benzylidene}piperidine-1-carboxamide) is a specific and irreversible inhibitor of FAAH1 [14]. Oral administration of PF-04457845 to rats in which pain had been induced using stimuli known to induce hyperalgesic inflammatory (complete Freund's adjuvant) or non-inflammatory (monosodium iodoacetate) states led to reduced responses that could be interpreted as indicative of analgesic properties for human chronic pain conditions [15]. Oral administration of PF-04457845 to rats also reduced FAAH1 activity and elevated concentrations of AEA in plasma and brain [15]. Notably near-complete inhibition of FAAH1 and maximal elevation of AEA were induced by doses of PF-04457845 required for efficacy in these rodent models.

As a first step in understanding the role of FAAH1 in pain pathways in humans, PF-04457845 has been administered to healthy human subjects and the pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD) and tolerability profiles have been examined. This manuscript describes three studies designed to investigate the PK, PD, PK/PD relationships and tolerability of single and multiple oral doses of PF-04457845 in healthy subjects. The relative bioavailability of a tablet and solution formulation and the effect of food on the PK of PF-04457845 were also assessed.

Methods

Subjects

Entry criteria for the study population was for healthy male and/or female subjects aged 18 to 55 years, with a body mass index of 18 to 30 kg m–2 and a body weight >50 kg. Female subjects had to be of non-childbearing potential (i.e. post menopausal or had undergone a hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy). All subjects had to be willing and able to comply with study procedures and all subjects had to provide written informed consent before participating. Exclusion criteria included current or history of clinically significant disease or a history of febrile illness within 5 days of the first dose of study drug, severe acute or chronic medical or psychiatric condition or laboratory abnormality that may have increased the risk to the subject or interfered with interpretation of study results, as well as other standardized criteria concerning allergies, QTc intervals, treatment with other investigational drugs, alcohol consumption and drug use. Use of concomitant medications (except ibuprofen), dietary and herbal supplements and consumption of grapefruit/pomelo-containing products was prohibited throughout the study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. All studies were conducted at the Pfizer Clinical Research Unit, Singapore and were approved by the Parkway Independent Ethics Committee, Singapore.

Study design

Two of the studies were double-blind (Sponsor open), placebo-controlled studies. Sponsor-open means that some of the Sponsor's staff could be unblinded, but at no point was any information of any relevance to blinding communicated to any investigator or subject. The single rising dose (SRD) study was a crossover study conducted in two cohorts of 12 subjects each. In study periods 1 to 3, subjects in cohort 1 received 0.1 mg, 1 mg and 10 mg PF-04457845 with placebo substitution, whilst subjects in cohort 2 received 0.3 mg, 3 mg and 20 mg with placebo substitution. Cohort 2 also had a fourth treatment period where subjects received either 40 mg PF-04457845 or placebo. Each dose was separated by a minimum of 14 days to allow washout of PF-04457845 and to allow for any elevations in FAAH1 to have returned to baseline. The multiple rising dose (MRD) study was a parallel group design with four cohorts of 10 subjects each (eight active, two placebo). PF-04457845 (0.5 mg, 1 mg, 4 mg and 8 mg) and placebo were administered once daily for 14 consecutive days. Doses for the SRD and MRD studies were administered in the fasted state, and PF-04457845 and placebo were administered as oral solutions in both studies. The third study was an open-label, single dose, crossover study to evaluate the relative bioavailability of PF-04457845 tablets compared with solution and to assess the effect of food on the tablet (food effect study). Subjects received, in random order, single oral doses of 8 mg PF-04457845 as tablets (8 × 1 mg) and as a solution in the fasted state and as tablets following a high fat breakfast. The components and timing of the high fat breakfast were in accordance with the FDA guidance on food-effect bioavailability studies [16].

Dose selection

The starting dose for the SRD study (0.1 mg PF-04457845) was projected from a preclinical PK/PD model to result in <1% inhibition of the FAAH1 enzyme. The maximum dose in the SRD study was limited by the no observable adverse effect level in the most sensitive species (dog) from the toxicology programme, which was associated with AUC(0,24 h) and Cmax values of 6290 ng ml−1 h and 482 ng ml−1 respectively. In non-clinical studies (toxicology and safety pharmacology) with PF-04457845, the male genital tract, liver and CNS had been identified as the main potential target organs (unpublished data). The dose regimens selected for the MRD study were aimed at achieving >97% inhibition of FAAH1 activity whilst not exceeding the toxicokinetic limits.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic methods

Blood samples were collected in the SRD study at intervals from pre dose until 264 h (11 days) after each dose. In the MRD study, pre dose blood samples were collected at intervals throughout the study period, whilst post dose samples were collected throughout days 1, 7 and 14 and subsequently at 24–48 h intervals up to the follow-up visit (14–21 days after the last dose). The blood samples in the SRD and MRD studies were split to provide a blood aliquot for leucocyte isolation (for assessment of FAAH1 activity), whilst the remaining sample was used to provide plasma for analysis of PF-04457845 and the fatty acid amides (AEA, LEA, OEA and PEA). Urine for analysis of PF-04457845 was collected over 24 h on day 14 of the MRD study. Blood samples for analysis of PF-04457845 concentrations only were collected in the food effect study at intervals from pre dose until 96 h post dose.

PF-04457845 was analyzed in plasma and urine using validated LC/MS/MS methods. Details of the analytical methods are available in Appendix S1 in the online version of this article. The calibration range for the plasma and urine assays was 0.100–100 ng ml−1, the lower limit of quantification was 0.1 ng ml−1, the between-day accuracy ranged from −8.8% to 5.3% over the QC range and the coefficients of variation (CVs) for assay precision were ≤7.7%. PK parameters were calculated using non-compartmental analysis. The following parameters were calculated as appropriate to each study; maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), minimum plasma concentration (Cmin), area under the concentration–time curve (AUC) to the last measurable time (AUC(0,tlast)), or over the dosing interval (AUC(0,τ)) or extrapolated to infinity (AUC(0,∞)), terminal elimination half-life (t1/2), accumulation ratio (Rac; calculated as AUC(0,τ)(day14) : AUC(0,τ)(day1), amount excreted in the urine (Ae) and renal clearance (CLr).

FAAH1 enzyme activity was measured in an ex vivo assay using isolated leucocytes as the source of the FAAH1 enzyme [17]. The activity of FAAH1 was measured as the concentration of deuterated ethanolamine produced from deuterated AEA. Samples were assayed for FAAH1 activity using a validated LCMS/MS method, with a calibration range of 10 to 10 000 nm. The between-day assay accuracy for FAAH1 activity ranged from −18.0% to 24.3% over the QC range and CVs for assay precision were ≤12.8%.

Plasma samples were analyzed for AEA, LEA, OEA and PEA concentrations using a validated LCMS/MS method [18], with calibration ranges of 0.05 to 10.0 ng ml−1 for AEA and LEA, 0.50 to 100 ng ml−1 for OEA and 1.00 to 200 ng ml−1 for PEA. The between-day accuracy for all the assays ranged from −9.0% to 8.6% and CVs for assay precision were ≤11.5%.

Cognitive function assessments

Cognitive function assessments were conducted in the SRD and MRD studies using an abbreviated CogState/Groton Maze Learning Test (GMLT) battery [19], [20]. These tests consisted of computerized tasks that assessed spatial memory and problem solving (using GMLT), psychomotor function (using simple reaction time), attention (using choice reaction time), and learning and memory (using the one-card learning test). In addition, GMLT delayed recall test was included in the MRD study. Subjects had two practice sessions at screening, followed by assessments at intervals throughout the study periods in both studies.

Safety

Safety assessments including adverse events monitoring, physical examinations, 12-lead ECGs, vital signs (blood pressure, pulse rate and body temperature) and laboratory safety tests were conducted at intervals throughout all studies. Continuous cardiac monitoring, via telemetry, was conducted up to 8 h post dose in the SRD study and up to 4 h post dose on days 1, 7 and 14 of the MRD study. All observed or reported AEs were recorded for all subjects and AEs were classified as mild, moderate or severe and their relationship to study drug was assessed by the investigator.

Statistical analysis

Subject numbers for the SRD or MRD studies were chosen based on the need to minimize exposure of a new chemical entity and the need to have sufficient subjects to enable useful conclusions to be drawn. More formal sample size calculations were not performed for these studies. For the food effect study, a sample size of 12 subjects provided 90% confidence intervals (CIs) for the difference between treatments of ±0.0905 and ±0.2091 on the natural log scale for AUC(0,∞) and Cmax respectively with 80% probability. In the MRD study, Rac was analyzed after natural log transformation using a one way analysis of variance (anova). Means and 90% CIs are presented. For assessment of food effect and relative bioavailability, natural log-transformed AUC(0,∞), AUC(0,tlast) and Cmax were analyzed using a mixed effect model. Estimates of the adjusted mean differences and corresponding 90% CIs were obtained and exponentiated to provide estimates of the ratio of adjusted geometric means (test : reference) and 90% CIs for the ratios.

The individual outcome measures and a composite change score for the cognitive function tests were analyzed using mixed linear analysis of covariance (ancova). Analyses and summarization of the CogState endpoints were conducted by CogState (Melbourne, Australia).

Results

Subjects

Seventy-seven healthy subjects were assigned to study treatment, 24 subjects in the SRD study, 41 in the MRD study and 12 in the food effect study. All subjects were male and aged between 21 and 48 years and the majority (76/77, 99%) were Asian. The demographic and baseline characteristics were similar between studies and treatment groups. No subjects withdrew from the SRD or food effect studies, whilst two subjects withdrew early from the MRD study (neither was due to adverse events).

Pharmacokinetic results

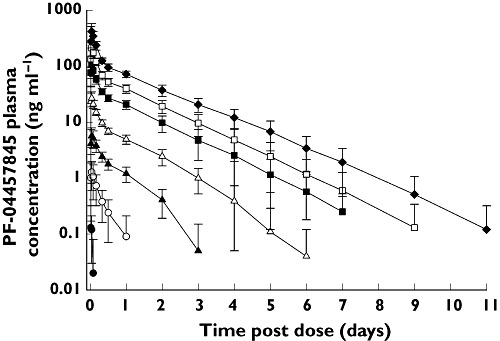

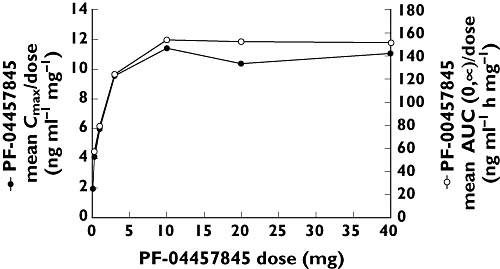

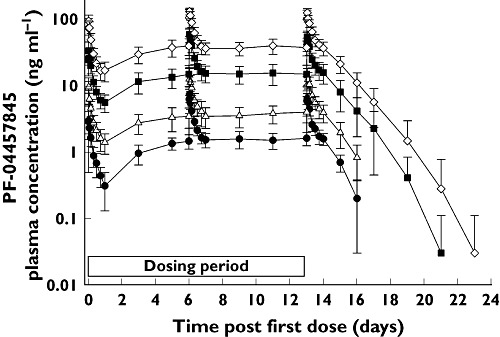

In the SRD study, there were supraproportional increases in PF-04457845 exposure following single oral doses ranging from 0.1 mg to 10 mg (Table 1, Figures 1 and 2). For single doses ranging from 10 mg to 40 mg and multiple doses ranging from 1 mg to 8 mg once daily, increases in exposure were consistent with increasing dose (Tables 1 and 2, Figures 1, 2 and 3). Following single and multiple dosing in the fasted state, PF-04457845 absorption was rapid, with median tmax values occurring between 0.5 and 1.2 h post dose. Following Cmax, plasma concentrations exhibited a multi-phasic decline over time with an apparent t1/2 of approximately 12 to 23 h. Inter-subject variability was low to moderate with CVs ranging from 17% to 67% for Cmax and AUC parameters across both studies. In the MRD study, steady-state appeared to have been achieved by day 7. PF-04457845 exposure increased with once daily dosing, with Rac ratios of approximately 2 to 3. Renal excretion was negligible with less than 0.1% of the dose being excreted in the urine at steady-state. Parameters describing the PK properties of PF-04457845 in healthy humans are presented in Table 1 (SRD study) and Table 2 (MRD study).

Table 1.

Summary of PF-04457845 pharmacokinetic parameters following single oral dosing (SRD study)

| PF-04457845 dose | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter* (units) | 0.1 mg | 0.3 mg | 1 mg | 3 mg | 10 mg | 20 mg | 40 mg |

| N, n | 7, 0 | 9, 4 | 9, 9 | 9, 9 | 9, 9 | 9, 9 | 9, 9 |

| AUC(0,∞) (ng ml−1 h) | NC | 17.2 (22) | 79.4 (30) | 372 (21) | 1537 (24) | 3041 (23) | 6048 (17) |

| AUC(0,tlast) (ng ml−1 h) | 0.091 (125) | 6.35 (66) | 72.6 (32) | 366 (21) | 1524 (24) | 3030 (23) | 5969 (18) |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 0.197 (67) | 1.23 (56) | 5.96 (37) | 28.6 (51) | 114 (18) | 207 (30) | 442 (34) |

| tmax (h) | 0.517 (0.50, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) |

| t1/2 (h) | NC | 11.6 (23) | 15.2 (16) | 16.2 (20) | 20.5 (30) | 21.1 (33) | 22.8 (29) |

Geometric mean (%CV) for all except median (min, max) for tmax; arithmetic mean (%CV) for t1/2. N = number of subjects contributing to mean PK parameters; n = number of subjects contributing to the mean for AUC(0,∞) and t1/2; NC = not calculated.

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) PF-04457845 plasma concentrations following single oral doses (SRD study). 0.1 mg (●), 0.3 mg (○), 1 mg (▴), 3 mg (▵), 10 mg ( ), 20 mg (□), 40 mg (◆)

), 20 mg (□), 40 mg (◆)

Figure 2.

Mean dose normalized Cmax (●) and AUC(0,∞) (○) vs.dose of PF-04457845 (SRD study)

Table 2.

Summary of PF-04457845 pharmacokinetic parameters following single and multiple oral dosing (MRD study)

| PF-04457845 dose regimen | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter* (Units) | 0.5 mg once daily | 1 mg once daily | 4 mg once daily | 8 mg once daily |

| Study day 1 | ||||

| N | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| AUC(0,τ) (ng ml−1 h) | 21.6 (25) | 68.3 (24) | 267 (28) | 724 (26) |

| Cmax,(ng ml−1) | 3.48 (56) | 10.6 (28) | 34.6 (42) | 92.8 (26) |

| tmax (h) | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.50, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.50, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.50, 1.00) |

| Study day 14 | ||||

| N, n | 8,7 | 8,8 | 7,7 | 8,8 |

| AUC(0,τ) (ng ml−1 h) | 65.5 (20) | 157 (27) | 585 (30) | 1420 (18) |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 6.93 (23) | 13.9 (29) | 53.7 (24) | 129 (17) |

| tmax (h) | 1.13 (0.50, 1.33) | 1.19 (0.53, 2.00) | 1.10 (1.08, 2.00) | 1.10 (0.50, 1.10) |

| Rac | 3.03 (20) | 2.30 (22) | 2.22 (12) | 1.96 (10) |

| t1/2 (h) | 18.5 (19) | 21.5 (21) | 20.0 (25) | 21.9 (25) |

| Ae (ng) | 0.000 (0) | 91.4 (141) | 3780 (70) | 3206 (57) |

| CLr (ml min−1) | ND | 0.0008 (5256) | 0.0869 (81) | 0.0341 (49) |

Geometric mean (%CV) for all except median (min, max) for tmax; arithmetic mean (%CV) for t1/2. Ae = amount excreted in the urine, AUC(0,τ) = area under the plasma concentration–time profile within the dosing interval of 0 to τ (24 h); CLr = renal clearance, Cmax = maximum observed concentration within the dosing interval, CV = coefficient of variation, N = number of subjects; n = number of subjects where t1/2 was determined, ND = not determined, Rac = accumulation ratio, t1/2 = terminal half-life, tmax = time to reach Cmax.

Figure 3.

Mean (SD) PF-04457845 plasma concentrations following once daily oral doses (MRD study). 0.5 mg (●), 1 mg (▵), 4 mg ( ), 8 mg (◊)

), 8 mg (◊)

The relative bioavailability of the tablet formulation compared with the solution was approximately 100% although the rate of absorption was different. Cmax was reduced by approximately 35% and delayed by approximately 1 h when PF-04457845 was administered as tablets compared with the solution (Table 3). A high fat meal had no effect on the PK of PF-04457845 when administered as tablets with 90% CIs for Cmax and AUC parameters all within the range of 80–125% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of statistical analysis of plasma PF-04457845 exposure (food effect study)

| 90% confidence interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter (units) | Ratio (%)* | Lower | Upper |

| Food effect (comparison: tablet fed vs. tablet fasted [8 mg PF-04457845]) | |||

| AUC(0,∞) (ng ml−1 h) | 104 | 98 | 111 |

| AUC(0,tlast) (ng ml−1 h) | 107 | 97 | 111 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 106 | 90 | 124 |

| Relative bioavailability (comparison: tablet vs. solution [8 mg PF-04457845]) | |||

| AUC(0,∞) (ng ml−1 h) | 103 | 97 | 110 |

| AUC(0,tlast) (ng ml−1 h) | 102 | 96 | 110 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 65 | 55 | 76 |

Ratio of adjusted geometric means. AUC(0,tlast) = area under the plasma concentration–time profile from time zero to the time of the last quantifiable concentration, AUC(0,∞) = area under the plasma concentration–time profile from time zero to infinity, Cmax = maximum observed concentration within the dosing interval.

Pharmacodynamic results

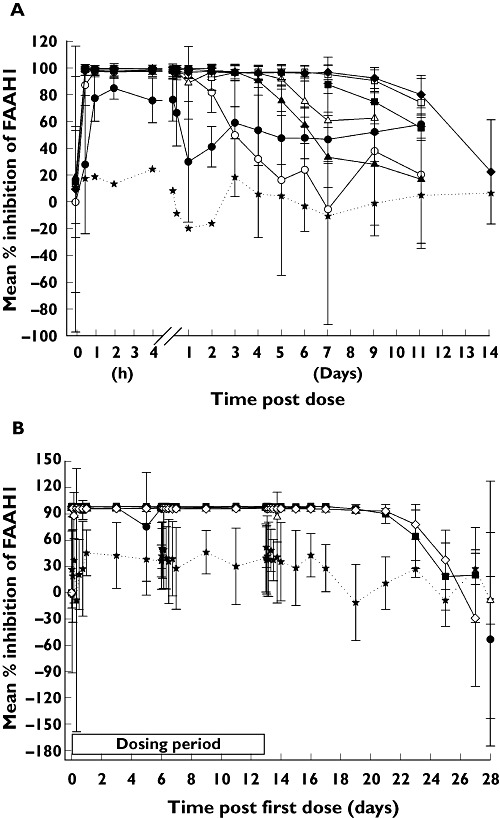

Single doses of PF-04457845 appeared to inhibit rapidly the FAAH1 enzyme with the maximum effect occurring within 2 h post dose (Table 4, Figure 4). Almost complete inhibition (>97%) of FAAH1 activity was observed following 0.3 mg PF-04457845 and above. The FAAH1 activity assay variability was notably lower in samples from subjects who had received PF-04457845 than those at baseline or following placebo. It is believed that this is due to the marked effect of PF-04457845 masking the inherent variability of the assay, arising primarily from the leucocyte isolation component. The inhibition was maintained for extended time periods following a single dose, the duration of which increased with increasing dose, e.g. FAAH1 activity returned to baseline by approximately 168 h (7 days) post dose following 0.3 mg PF-04457845, whilst activity did not return to baseline until approximately 336 h (14 days) post dose following 40 mg PF-04457845.

Table 4.

Maximum mean % inhibition (from baseline) of FAAH1 activity in human leucocytes (SRD and MRD studies)

| SRD study | Placebo (n = 21) | 0.1 mg (n = 9) | 0.3 mg (n = 9) | 1 mg (n = 9) | 3 mg (n = 9) | 10 mg (n=9) | 20 mg (n=9) | 40 mg (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAAH1 % inhibition * | 24.3 (38.89) | 84.2 (8.06) | 96.9 (1.46) | 98.6 (0.56) | 97.8 (3.44) | 99.0 (0.39) | 96.1 (5.19) | 97.2 (3.54) |

| MRD study | Placebo (n = 8) | 0.5 mg once daily (n = 8) | 1 mg once daily (n = 8) | 4 mg once daily (n = 8) | 8 mg once daily (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAAH1 % inhibition * | 52.0 (23.3) | 98.2 (0.98) | 97.6 (0.45) | 98.9 (0.49) | 97.2 (1.94) |

Values are means (SD).

Figure 4.

(A) Mean (SD) % inhibition of FAAH1 following single oral doses of PF-04457845 (SRD study). Placebo (★), 0.1 mg (●), 0.3 mg (○), 1 mg (▴), 3 mg (▵), 10 mg ( ), 20 mg (□), 40 mg (◆). The SDs have been omitted from the placebo line as they were large (average 73%) and obscure the SDs for the active doses. (B) Mean (SD) % inhibition of FAAH1 following once daily oral doses of PF-04457845 (MRD study). Placebo (★), 0.5 mg (●), 1 mg (▵), 4 mg (

), 20 mg (□), 40 mg (◆). The SDs have been omitted from the placebo line as they were large (average 73%) and obscure the SDs for the active doses. (B) Mean (SD) % inhibition of FAAH1 following once daily oral doses of PF-04457845 (MRD study). Placebo (★), 0.5 mg (●), 1 mg (▵), 4 mg ( ), 8 mg (◊)

), 8 mg (◊)

In the MRD study, all dose regimens (0.5 mg to 8 mg once daily PF-04457845) demonstrated rapid and sustained inhibition of FAAH1 activity (Table 4, Figure 4), with all doses achieving >97% inhibition. Increasing the dose of PF-04457845 above 0.5 mg once daily did not provide increased FAAH1 inhibition. This maximal inhibition was maintained for at least 1 week after the last dose for all dose regimens, with FAAH1 activity not returning to baseline until up to 2 weeks after the last dose up to 4 mg once daily.

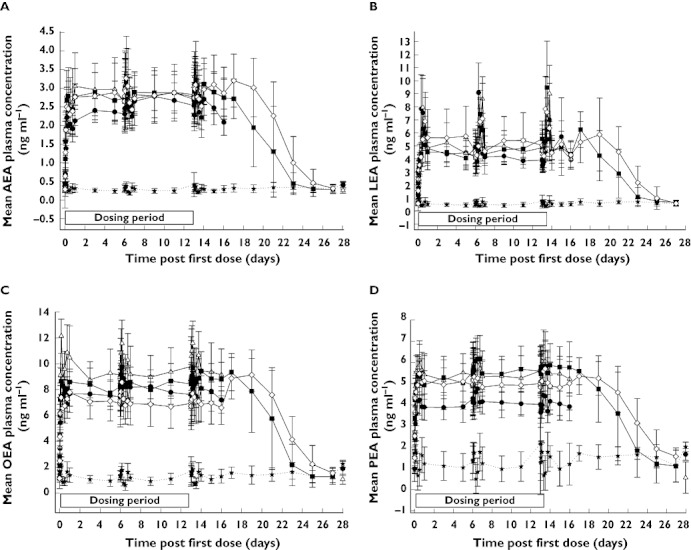

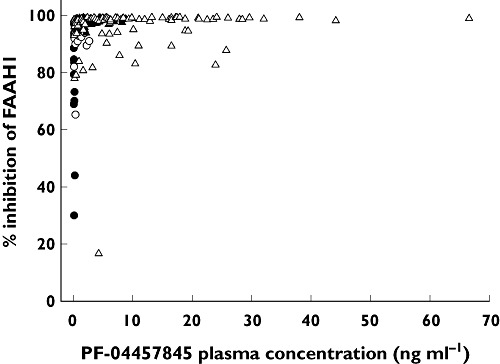

AEA, LEA, OEA and PEA plasma concentrations increased significantly to a plateau following single and multiple doses of PF-04457845. In the MRD study, these elevations were similar for each fatty acid amide across all doses (0.5 to 8 mg once daily PF-04457845; Figure 5) and were maintained for several days after the last dose on day 14. For example, the mean PD endpoints (FAAH1 activity and fatty acid amide concentrations) took 10 to 12 days following the last dose of 4 mg once daily PF-04457845 to return to baseline. On average the concentrations of each fatty acid amide on day 14 were approximately 10-fold (AEA), 6-fold (OEA), 9-fold (LEA) and 3.5-fold (PEA) higher following PF-04457845 than placebo. Comparison of the AEA time course data with the FAAH1 inhibition data suggests that at least 97% FAAH1 inhibition was required to maintain elevations of AEA. Examination of the relationship between FAAH1 inhibition and PF-04457845 concentration showed that concentrations of at least ∼1 ng ml−1 PF-04457845 were required to maintain inhibition of FAAH1 activity by at least 97% (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Mean (SD) elevation of AEA (A), LEA (B), OEA (C) and PEA (D) following once daily oral doses of PF-04457845 (MRD study). Placebo (★), 0.5 mg (●), 1 mg (▵), 4 mg ( ), 8 mg (◊)

), 8 mg (◊)

Figure 6.

The relationship between PF-04457845 plasma concentrations and FAAH1 inhibition at doses up to 10 mg PF-04457845 (SRD study), 0.1 mg (●), 0.3 mg (○), 1 mg (▴), 3 mg (▵), 10 mg ( ). (Higher doses are entirely compatible with the emergent pattern but are not included as the amount of data at high concentrations obscures the relationship.)

). (Higher doses are entirely compatible with the emergent pattern but are not included as the amount of data at high concentrations obscures the relationship.)

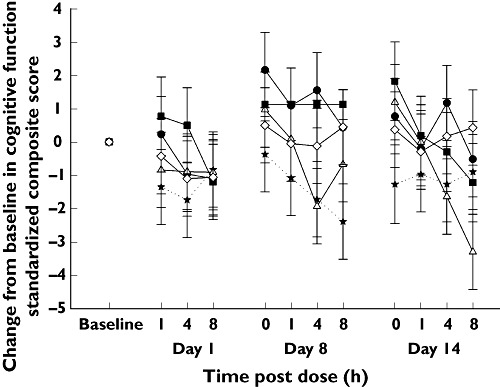

There were no significant differences between placebo and any dose of PF-04457845 for any of the cognitive function tests performed in either the SRD or MRD studies whether results were examined on an individual test basis or as a composite score (as shown in Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Mean (SE) change from baseline in standardized composite score of the cognitive function tests following once daily oral doses of PF-04457845 (MRD study). Placebo (★), 0.5 mg (●), 1 mg (▵), 4 mg ( ), 8 mg (◊)

), 8 mg (◊)

Safety

There were no deaths, other serious or severe adverse events or discontinuations due to adverse events during any of the studies. A total of 29 adverse events were reported in the SRD study, of which five were considered to be treatment-related (one due to placebo and four due to PF-04457845). Somnolence was the only treatment-related adverse event to be reported by more than one subject in the SRD study. A total of 24 adverse events were reported in the MRD study, of which 18 were considered to be treatment-related (four due to placebo, 16 due to PF-04457845). The only treatment-related adverse events in the MRD study reported by more than one subject were hard faeces (six subjects) and headache (three subjects). Only two adverse events were reported in the food effect study, of which one adverse event (arthralgia) was considered to be treatment-related. Adverse events reported by at least two subjects in the SRD and MRD studies are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of adverse events reported by least two subjects in each study

| SRD study | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF-04457845 dose | |||||||||

| Adverse event | Placebo Cohort 1* (n = 9) | Cohort 2† (n = 12) | 0.1 mg (n = 9) | 0.3 mg (n = 9) | 1 mg (n = 9) | 3 mg (n = 9) | 10 mg (n=9) | 20 mg (n=9) | 40 mg (n=9) |

| Number of subjects with adverse events | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Number of subjects with treatment-related adverse events | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Excoriation | 1 (0) | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 2 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Somnolence | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Eye pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Pyrexia | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Rhinorrhoea | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| MRD study | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF-04457845 dose | |||||

| Adverse event | Placebo (n = 8) | 0.5 mg once daily (n = 8) | 1 mg once daily (n = 8) | 4 mg once daily (n = 8) | 8 mg once daily (n = 8) |

| Number of subjects with adverse events | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Number of subjects with treatment-related adverse events | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Faeces hard | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 0 | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Values are numbers of subjects with adverse events (treatment-related adverse events).

Subjects in cohort 1 received placebo, 0.1 mg, 1 mg and 10 mg PF-04457845.

Subjects in cohort 2 received placebo, 0.3 mg, 3 mg, 20 mg and 40 mg PF-04457845.

No subject or group of subjects showed any clinically relevant change in supine or standing blood pressure (systolic or diastolic) throughout the studies, any evidence from vital signs of postural hypotension, or any clinically relevant effects on ECG parameters, including QTc interval (data not shown). There were no treatment-related laboratory safety parameters of clinical significance (data not shown).

Discussion

PF-04457845 is the first inhibitor of FAAH1 that has been dosed to humans. It was well tolerated after single oral doses from 0.1 to 40 mg, and when administered on multiple occasions from 0.5 to 8 mg once daily for 14 days. At single doses of 0.3 mg or above or multiple doses of 0.5 mg once daily or above, FAAH1 was inhibited nearly completely (>97%), with a time course that can be described as fast onset (maximal mean inhibition observed within 2 h post dose) and prolonged (FAAH1 activity took 1 to 2 weeks to return to baseline depending on the dose), in accordance with the known tmax of plasma PF-044587845 exposure and the irreversible mechanism of inhibition [14], [15].

Despite escalating to both single and multiple doses of PF-04457845 that achieved maximal effects on inhibition of leucocyte FAAH1 activity and plasma fatty acid amide concentrations, PF-04457845 was well-tolerated by all subjects to whom it had been dosed. Overall, the nature and incidence of adverse events following PF-04457845 appeared similar to placebo and there was no evidence of any dose-related adverse events. The bland adverse event profile is in accordance with the knock-out mouse phenotype, where the differences from wild type mice were only seen in conditions of stress, such as pain stimuli [5]–[8].

Notably, there was no evidence in these studies of adverse effects commonly associated with cannabinoids, such as impaired cognition, motor control or psychogenic effects. The reason for this apparent separation of effects remains unclear and therefore further investigation would be warranted. Of course, the elevations in fatty acid amides (due to inhibition of FAAH1) may affect mechanisms in addition to those involved in cannabinoid pathways [21]. Evidence of the activation of such mechanisms, such as changes in appetite or sleep, was not observed in these studies from the adverse events profile (with the exception of isolated reports of mild somnolence that were not dose related). However, it should be noted that specific endpoints related to such mechanisms were not included in these studies, although no evidence of sedation could be observed from the use of a cognitive battery that is more sensitive than voluntary elicitation of adverse events [19].

PF-04457845, an orally available FAAH1 inhibitor, has demonstrated variable pharmacokinetic properties in human subjects. The distinct dose-dependent Cmax and AUC(0,∞) following single dose administration signifies a typical target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD) phenomenon, which is commonly observed for large biological antibodies [22] and less often with small molecule compounds [23], [24]. The TMDD is most likely to be caused by a capacity-limited irreversible binding of PF-04457845 to the FAAH1 enzyme present in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. This explanation is supported by the research evidence of the distribution of FAAH1 activity and mRNA in these organs from rat, mouse and humans [25]. This specific binding to FAAH1 is therefore thought to account for the nonproportional PK of PF-04457845 at lower doses. At higher doses, this mechanism is saturated and the disposition of PF-04457845 is governed by hepatic metabolism resulting in linear PK.

In the MRD study, however, Cmax and AUC(0,τ) observed on day 14 appeared to increase proportionally to dose over the range studied. Thus at these doses (0.5 to 8 mg) the nonlinear pathway appeared of little importance in defining the steady-state concentrations. Additional linear pathway(s) appeared to dominate the overall elimination of the compound at steady-state.

The residual FAAH1 activity in blood leucocytes and the plasma concentrations of the fatty acid amides that were evaluated in these phase 1 studies have been identified as translational PD biomarkers i.e. biomarkers that can be measured in a similar manner in more than one species to indicate that broadly similar target occupancy and downstream effects are achieved by PF-04457845 across species, in this case rat and human. In rodent behavioural animal models [15], inhibition of leucocyte FAAH1 activity by approximately 97% was necessary to achieve anti-nociceptive effects, and the same levels of inhibition were required to elevate plasma fatty acid amide concentrations to a maximal degree. The studies reported here confirm that a similar relationship exists between the degree of FAAH1 inhibition and the degree of elevation of plasma fatty acid amides in humans.

In comparison with the rapid decline in PK following single or multiple dosing, the PD profiles observed in these studies revealed more prolonged effects on FAAH1 inhibition and fatty acid amide elevation than would have been expected from the PK terminal half-life (∼20 h) of PF-04457845. The visual exploration of the FAAH1 % inhibition in relation to PF-04457845 plasma concentration showed a typical all-or-nothing steep PK/PD relationship. These observations are in accordance with the irreversible inhibition mechanism of action [26], [27]. The recovery of FAAH1 activity is not directly driven by the concentration of PF-04457845 but probably depends on the slow endogenous synthesis of the FAAH1 enzyme.

In addition, inhibition of the FAAH1 enzyme resulted in substantial accumulation of several fatty acid amides including AEA, PEA, OEA and LEA, consistent with the fact that they are known as FAAH1 substrates and FAAH1 is believed to be the principal enzyme in their catabolic pathways [3]. The fact that the maximal extent of fatty acid amide increases in man is independent of dose, similar to the results observed in rodents, suggests that there is a system-capped maximal capacity for FAAH1-inhibition by PF-04458745 to produce endocannabinoids. Possible explanations for such a profile include the existence of either additional catabolic pathways or a negative feedback mechanism on fatty acid amide synthetic routes [3]. FAAH2 enzyme and N-acyl-ethanolamine (NAE)-hydrolyzing acid amidase (NAAA) have been reported as additional enzymes that hydrolyze AEA. Unlike FAAH1, FAAH2 is preferentially expressed in select peripheral tissues such as heart and ovary [3]. Unlike FAAH1, which preferentially hydrolyzes AEA as a substrate, NAAA hydrolyzes PEA much faster than any other NAEs in some conditions (see [3]).

Whilst the SRD (first-in-human) study with this irreversible inhibitor was conducted with due caution because of the potential for long lasting safety issues, the safety and tolerability profile observed after administration to humans was good. FAAH activity returned to baseline after 1–2 weeks (depending on dose), indicating that the irreversible nature of PF-04457845 offered a pharmacological advantage, effectively reducing the dose required for prolonged elevation of fatty acid amide concentrations.

Overall, the data from these studies support the continued evaluation of PF-04457845 to investigate whether the effects of fatty acid amide elevation translate to analgesic effects or other effects of benefit to patients. For subsequent patient studies, doses of at least 0.5 mg once daily should be sufficient, well tolerated and provide maximal effects on FAAH1 activity and fatty acid amide elevation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and subjects who participated in this research, Kuntal Sinha (Pfizer) who was responsible for the analysis of PF-04457845, Kathryn Wright (Pfizer) who was responsible for oversight of the analysis of FAAH1 activity and fatty acid amide concentrations and Deborah Russell (Pfizer) who was responsible for the operational aspects of the studies described here and Paul Maruff (CogState Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) who was responsible for the cognitive function assessments. The authors would also like to thank Samantha Abel (Valley Writing Solutions Ltd) for professional medical writing assistance, including preparation of the initial draft based on discussions with the authors, coordination of author review, updates based on author comments and management of the journal submission procedure. Cogstate Ltd and Valley Writing Solutions Ltd were both funded by Pfizer.

Competing Interests

The study was sponsored by Pfizer Worldwide Research and Development and all authors are current or former employees of Pfizer.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix S1

Analytical method for the analysis of PF-04457845 inK2EDTA plasma

REFERENCES

- 1.Rice ASC, Lever I, Zarnegar R. Cannabinoids and analgesia, with special reference to neuropathic pain. In: McQuay HJ, Kalso E, Moore RA, editors. Systematic Reviews in Pain Research: Methodology Refined. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 2008. pp. 233–46. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware MA, Tawfik BL. Safety issues concerning the medical use of cannabis and cannabinoids. Pain Res Manag. 2005;10(Suppl. A):31A–7A. doi: 10.1155/2005/312357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn K, McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Enzymatic pathways that regulate endocannabinoid signaling in the nervous system. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1687–707. doi: 10.1021/cr0782067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn K, Johnson DS, Cravatt BF. Fatty acid amide hydrolase as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of pain and CNS disorders. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2009;4:763–84. doi: 10.1517/17460440903018857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cravatt BF, Demarest K, Patricelli MP, Bracey MH, Giang DK, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9371–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtman AH, Shelton CC, Advani T, Cravatt BF. Mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase exhibit a cannabinoid receptor-mediated phenotypic hypoalgesia. Pain. 2004;109:319–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wise LE, Shelton CC, Cravatt BF, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Assessment of anandamide's pharmacological effects in mice deficient of both fatty acid amide hydolase and cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:44–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huitron-Resendiz S, Sanchez-Alavez M, Wills DN, Cravatt BF, Henriksen SJ. Characterization of the sleep-wake patterns in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Sleep. 2004;27:857–65. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boger DL, Sato H, Lerner AE, Hedrick MP, Fecik RA, Miyauchi H, Wilkie GD, Austin BJ, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Exceptionally potent inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase: the enzyme responsible for degradation of endogenous oleamide and anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5044–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang L, Luo L, Palmer JA, Sutton S, Wilson SJ, Barbier AJ, Breitenbucher JG, Chaplan SR, Webb M. Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase produces analgesia by multiple mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:102–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtman AH, Leung D, Shelton CC, Saghatelian A, Hardouin C, Boger DL, Cravatt BF. Reversible inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase that promote analgesia: evidence for an unprecedented combination of potency and selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:441–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valino F, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, La Rana G, Calignano A, Giustino A, Tattoli M, Palmery M, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russo R, Loverme J, La Rana G, Compton TR, Parrott J, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, Calignano A, Piomelli D. The fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB597 (cyclohexylcarbamic acid 3′-carbamoylbiphenyl-3-yl ester) reduces neuropathic pain after oral administration in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:236–42. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson DS, Stiff C, Lazerwith SE, Kesten SR, Fay LK, Morris M, Beidler D, Liimatta MB, Smith SE, Dudley DT, Sadagopan N, Bhattachar SN, Kesten SJ, Nomanbhoy TK, Cravatt BF, Ahn K. Discovery of PF-04457845: a highly potent, orally bioavailable and selective urea FAAH inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2:91–6. doi: 10.1021/ml100190t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn K, Smith SE, Liimatta MB, Beidler D, Sadagopan N, Dudley DT, Young T, Wren P, Zhang Y, Swaney S, Van Becelaere K, Blankman JL, Nomura DK, Bhattachar SN, Stiff C, Nomanbhoy TK, Weerapana E, Johnson DS, Cravatt BF. Mechanistic and pharmacological characterization of PF-04457845: a highly potent and selective FAAH inhibitor that reduces inflammatory and noninflammatory pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:114–24. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.180257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Food-effect bioavailability and fed bioequivalence studies. 2002. 1–12. Available from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM126833.pdf (last accessed May 2011)

- 17.Yapa U, Prsakiewicz JJ, Wrightstone AD, Christine LJ, Palandra J, Groeber E, Wittwer AJ. HPLC-MS/MS assay of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) in blood: FAAH inhibition as clinical biomarker. Anal Biochem. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.042. DOI: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palandra J, Prusakiewicz J, Ozer JS, Zhang Y, Heath TG. Endogenous ethanolamide analysis in human plasma using HPLC tandem MS with electrospray ionization. J Chromatogr B. 2009;877:2052–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collie A, Maruff P, Snyder PJ, Darekar MA, Huggins JP. Cognitive testing in early phase clinical trials: outcome according to adverse event profile in a Phase I study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:481–8. doi: 10.1002/hup.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collie A, Darekar A, Weissgerber G, Toh MK, Snyder PJ, Maruff P, Huggins JP. Cognitive testing in early-phase clinical trials: development of a rapid computerized test battery and application in a simulated Phase I study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa B, Comelli F, Bettoni I, Colleoni M, Giagnoni G. The endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitoylethanolamide, has anti-allodynic and anti-hyperalgesic effects in a murine model of neuropathic pain: involvement of CB1, TRPV1 and PPARγ receptors and neurotrophic factors. Pain. 2008;139:541–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lobo ED, Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:2645–68. doi: 10.1002/jps.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy G. Pharmacologic target-mediated drug disposition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;56:248–52. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gisleskog PO, Hermann D, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Karlsson MO. The pharmacokinetic modelling of GI198745 (dutasteride), a compound with parallel linear and nonlinear elimination. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:53–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisogno T, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. Fatty acid amide hydrolase, an enzyme with many bioactive substrates. Possible therapeutic implications. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:125–33. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gisleskog PO, Hermann D, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Karlsson MO. A model for the turnover of dihydrotestosterone in the presence of the irreversible 5α-reductase inhibitors GI198745 and finasteride. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:636–47. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swinney DC. Biochemical mechanisms of drug action: what does it take for success? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:801–8. doi: 10.1038/nrd1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.