Abstract

AIM

The contribution of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to injurious fall risk in patients with dementia has not been quantified precisely until now. Our objective was to determine whether a dose–response relationship exists for the use of SSRIs and injurious falls in a population of nursing home residents with dementia.

METHODS

Daily drug use and daily falls were recorded in 248 nursing home residents with dementia from 1 January 2006 until 1 January 2008. For each resident and for each day of the study period, data on drug use were abstracted from the prescription database, and information on falls and subsequent injuries was retrieved from a standardized incident report system, resulting in a dataset of 85 074 person-days.

RESULTS

We found a significant dose–response relationship between injurious falls and the use of SSRIs. The risk of an injurious fall increased significantly with 31% at 0.25 of the Defined Daily Dose (DDD) of a SSRI, 73% at 0.50 DDD, and 198% at 1.00 DDD (Hazard ratio = 2.98; 95% confidence interval 1.94, 4.57). The risk increased further in combination with a hypnotic or sedative.

CONCLUSIONS

Even at low doses, SSRIs are associated with increased risk of an injurious fall in nursing home residents with dementia. Higher doses increase the risk further with a three-fold risk at 1.00 DDD. New treatment protocols might be needed that take into account the dose–response relationship between SSRIs and injurious falls.

Keywords: dementia, dose–response, falls, nursing homes, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Patients treated with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to have an increased risk of falling. In nursing homes, many patients with dementia are given SSRIs as a treatment for depression. In this group, however, the possible risk of injurious falls by treatment dosage is not known.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Even at low doses, SSRIs are associated with increased risk of an injurious fall in nursing home residents with dementia. The risk increases with higher doses, with a three-fold increased risk at 1.00 Defined Daily Dose. The combination of a SSRI with a hypnotic or sedative increases the risk even further.

Introduction

Falls are a major health problem among the elderly, particularly in nursing homes [1], [2]. In nursing homes one-third of all falls results in an injury [3]. Nursing home residents with dementia are at particular risk of falling, with an average of more than two falls per bed per year [4].

In order to take tailor-made preventive measures in time, the fall risk profile of each individual nursing home resident should be periodically evaluated. A systematic evaluation of fall risk should include an assessment of all major contributing components, including the use of medication [5], [6]. Depressive symptoms are common in patients with dementia [7]. Therefore, a high proportion of nursing home residents with dementia are treated with antidepressants [8]–[10], including selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are generally considered the treatment of choice for depression in dementia [11]. However, recent research has shown that use of SSRIs is associated with an increased risk of injurious falls and fractures [12]–[14], and that there is a dose-dependent relationship between the use of SSRIs and fracture risk in the general population [15].

So far, data on the association between use of SSRIs and injurious fall risk in the specific population of nursing home residents with dementia are lacking [16]. Therefore we addressed the question:

Is there a dose–response relationship between the use of SSRIs and injurious falls in a population of nursing home residents with dementia?

Methods

Design and setting

For this retrospective study we included all eligible nursing home residents with dementia living in the psychogeriatric nursing home Smeetsland (De StromenOpmaatGroep), in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. We analyzed daily drug use and daily falls over a 2 year period, i.e. from 1 January 2006 until 1 January 2008. We collected data from residents, who were resident for at least 6 weeks, and who were able to walk independently, with or without a walking aid. Information on the ambulatory status (able/unable to walk independently) was retrieved from the medical records and nursing home charts. Reasons to end data collection were immobility, death or discharge. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Center approved the study.

Dementia diagnosis and severity

All residents in the nursing home met the criteria for the diagnosis of dementia from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) [17]. Severity of dementia was defined as stage 5 or 6 on the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) [18], and was based on the regular multidisciplinary team assessment by the nursing home staff, including the nursing home physician.

Drug use

For each resident and for each day of the study period, we extracted the use and dose of SSRIs and other fall-risk-increasing drugs (FRIDs) from the prescription database in the medical records. These drugs included antipsychotic drugs, anxiolytics, hypnotics or sedatives, other antidepressants, drugs used in diabetes, cardiovascular drugs, β-adrenoceptor blocker eye drops, analgesics, anticholinergic drugs, antihistamines and antivertigo drugs [19]–[22].

Drugs were coded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system and doses were recorded and expressed as a proportion of the Defined Daily Dose (DDD), i.e. the average of a dosage of a drug taken by adults for the main indication as indicated by the World Health Organization [23]. As an example from the ATC classification system, 1 DDD citalopram is a dosage of 20 mg [23]. We expressed 10 mg citalopram as 0.5 DDD.

We accessed the P450 Drug Interaction Table to retrieve information about cytochrome P450 enzymes that metabolize the prescribed SSRIs in our dataset [24]. We then explored our dataset to check for the combined use of a SSRI and a cytochrome P450 (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, and 2D6 pathways) inhibitor because SSRIs may become long-acting, when co-administered with an inhibitor, thereby increasing the risk further. We considered strong, moderate and weak inhibitors [24].

Patient characteristics

Baseline data collected from medical records and nursing home charts were age, gender and comorbid conditions that are considered potentially causative of falls. These comorbid conditions included visual impairment, urinary incontinence, Parkinson's disease, arthritis and other joint diseases, depression and cardiovascular diseases [25], [26].

Injurious falls

A fall was defined as unintentionally coming to rest on the ground or any other lower level [27]. Falls were recorded on a standardized incidence registration form [28]. This incidence registration form is part of the incidence registration system. This standard procedure is a national instrument to monitor the quality of care in nursing homes in the Netherlands [29]. The staff were trained to complete the forms immediately after a fall took place, or after a resident was found on the floor or any other lower level. A committee collected and processed the forms in the computer, and provided incidence reports. For each day of the study period falls and information on subsequent injuries were obtained from these computerized reports. Injurious falls were categorized as falls resulting in fractures, grazes, open wounds, sprains, bruises and swellings.

Falls history

Because a positive falls history is a known risk factor for further falls, we also collected data on falls in the year before the start of the study from this computer system, i.e. from 1 January 2005 until 1 January 2006.

Statistical analysis

To assess the dose–response relationship we defined SSRI use and all other FRID use as a continuous variable, expressed as a proportion of the DDD on a daily basis. To analyze the relation between drug use and the incidence of injurious falls we used multilevel logistic regression with ‘days-per-resident’ as unit of analysis and ‘resident’ as cluster variable. We had observations about many days for each resident. The outcome variable was whether a resident had experienced an injurious fall on any given day; we assumed the number of injurious falls per day to have a binominal distribution. For every day observed we have registered the type and number of drugs administered to that resident. We expected every resident to have a personal expected probability of injurious falls, so a random intercept per person was added to the model. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all variables (i.e. psychotropic drugs, other FRIDs, co-morbidities, falls in the previous year, age and gender). All variables that were significant in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. The initial multivariate model included variables associated with falls (P≤ 0.05). The model was then reduced by backward elimination to exclude factors that did not reach significance (at P≤ 0.05). To examine significant interactions between the variables in the final multivariate model, interaction terms were calculated and added to the model.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 16.0, SPSS INC., Chicago, IL, USA), and R (package lme4, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [30], [31].

Results

During the study period, a total of 443 persons were residents in the psychogeriatric nursing home Smeetsland. Seventy-four persons were excluded because they were residents for less than 6 weeks. One hundred twenty-one residents were excluded because they were not able to walk independently at the start of the data collection. The data of 248 residents were included in the study. The data collection resulted in a dataset of 85 074 person-days. Mean time spent in the database was 350 days. The mean age (SD) of the participants was 82 (8) years. During 85 074 person-days, 152 (61.5%) of the residents sustained 683 falls, which corresponds to a fall incidence of 2.9 falls/person-year. Thirty-eight residents (15.4%) were single fallers and 114 (46.2%) were frequent fallers.

Two hundred and twenty (32.2%) falls resulted in an injury. One person died, 21 (3.1%) falls resulted in a fracture, of which 10 (1.5%) were hip fractures and 11 (1.6%) other fractures. One hundred and ninety-eight (30.0%) falls resulted in injuries other than fractures, such as grazes, open wounds, sprains, bruises and swellings. Characteristics of the study population and incidence of injurious falls are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population, and person-days with and without injurious falls

| Characteristics | All person-days (n = 85 074) n (% of total) | Person-days with injurious fall (n = 220) n (% of total) | Person-days without injurious fall (n = 84 854) n (% of total) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 34 282 (40.3) | 92 (41.8%) | 34 190 (40.3%) | |

| Female | 50 792 (59.7) | 128 (58.2%) | 50 664 (59.7%) | |

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 82.8 (6.5) | 81.0 (8.0) | ||

| Falls history | 45 982 (54.0) | 168 (19.1%) | 45 814 (20.5%) | 0.62 |

| Visual impairment | 18 139 (21.3) | 38 (17.3%) | 18 101 (21.3%) | 0.14 |

| Urinary incontinence | 44 310 (52.1) | 124 (56.4%) | 44 310 (52.0%) | 0.20 |

| Parkinson's disease | 1 151 (1.4) | 3 (1.4%) | 1 151 (1.4%) | 0.99 |

| Arthritis and other joint diseases | 23 074 (27.1) | 75 (34.1%) | 22 999 (27.1%) | 0.02 |

| Depression | 7 161 (8.4) | 26 (11.8%) | 7 135 (8.4%) | 0.07 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 61 123 (71.8) | 165 (75.0%) | 60 958 (71.8%) | 0.29 |

| Drug use | ||||

| Antipsychotics (ATC-code N05A) | 38 662 (45.4) | 126 (57.3%) | 38 536 (45.4%) | 0.00 |

| Anxiolytics (ATC-code N05B) | 17 781 (20.9) | 58 (26.4%) | 17 723 (20.9%) | 0.05 |

| Hypnotics or sedatives (ATC-code N05C) | 11 538 (13.6) | 44 (20.0%) | 11 494 (13.5%) | 0.01 |

| Antidepressants (ATC-code N06A) | 13 729 (16.1) | 62 (28.2%) | 13 667 (16.1%) | 0.00 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants (ATC-code N06AA) | 1 141 (1.3) | 2 (0.9%) | 1 139 (1.3%) | 0.58 |

| Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (ATC-code N06AB) | 11 105 (13.1) | 55 (25.0%) | 11 050 (13.0%) | 0.00 |

| Other antidepressants (ATC-code N06AX) | 1 739 (2.0) | 5 (2.3%) | 1 734 (2.0%) | 0.81 |

| Antihypertensives (ATC-codes C02, C03, C07, C08, C09) | 12 081 (14.2) | 41 (18.6%) | 12 040 (14.2%) | 0.06 |

| Anti-arrhythmics (ATC code C01B) | 8 069 (9.5) | 24 (10.9%) | 8 045 (9.5%) | 0.47 |

| Nitrates and other vasodilators (ATC code C01D) | 2 830 (3.3) | 7 (3.2%) | 2 823 (3.3%) | 0.91 |

| Digoxin (ATC code C01AA05) | 2 865 (3.4) | 7 (3.2%) | 2 858 (3.4%) | 0.88 |

| β-adrenoceptor blocker eye drops (ATC code S01ED) | 798 (0.9) | 3 (1.4%) | 795 (0.9%) | 0.51 |

| Analgesics (ATC code N02) | 1 684 (2.0) | 5 (2.3%) | 1 679 (2.0%) | 0.76 |

| Anticholinergic drugs (ATC codes R03BB01, G04BD07) | 138 (0.2) | 0 (0.0%) | 138 (0.2%) | 0.55 |

| Antihistamines (ATC code R06) | 2 538 (3.0) | 4 (1.8%) | 2 534 (3.0%) | 0.31 |

| Antivertigo drugs (ATC code N07C) | 202 (0.2) | 0 (0.0%) | 202 (0.2%) | 0.47 |

| Drugs used in diabetes (ATC code A10) | 5 172 (6.1) | 13 (5.9%) | 5 159 (6.1%) | 0.92 |

Prevalence of antidepressant use

During a total of 13 729 (16.1%) person-days an antidepressant was used, of which 11 105 (13.1%) person-days concerned the use of a SSRI (mean DDD = 0.95, SD = 0.28). The SSRIs used were citalopram (6969 person-days, mean DDD = 0.96, SD = 0.28), paroxetine (4199 person-days, mean DDD = 0.89, SD = 0.25), sertraline (116 person-days, DDD = 1.00) and fluvoxamine (43 person-days, DDD = 0.40). Tricyclic antidepressants used were amitriptyline (75 person-days, mean DDD = 0.20, SD = 0.07) and nortriptyline (1066 person-days, mean DDD = 0.62, SD = 0.36). Other antidepressants used were trazodone (847 person-days, mean DDD = 0.37, SD = 0.18) and mirtazapine (892 person-days, mean DDD = 0.80, SD = 0.25). We found no person-days of SSRIs co-administered with a cytochrome P450 (1A2, 2C9, 2C19 and 2D6 pathways) inhibitor [24].

Risk of an injurious fall

Table 2 presents the univariate HRs for injurious falls. The results of the multivariate analysis are presented in Table 3. The risk of an injurious fall increased with age (HR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01, 1.09). The risk of an injurious fall also increased with the use of antipsychotics (HR 1.76, 95% CI 1.18, 2.63), and antidepressants (HR 2.58, 95% CI 1.57, 4.24). Analysis of subgroups of antidepressants showed that only the use of SSRIs (HR 2.50, 95% CI 1.50, 4.19) remained significant.

Table 2.

Univariate hazard ratios for injurious falls

| Characteristics | HR Injurious falls (95% CI) | P | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 0.93 (0.55, 1.56) | 0.77 | ||

| Female | ref | |||

| Age(continuous variable)† | *1.04 (1.01, 1.08) | 0.02 | ||

| Falls history | 0.97 (0.48, 1.95) | 0.93 | ||

| Visual impairment | 0.86 (0.45, 1.63) | 0.64 | ||

| Urinary incontinence | 1.16 (0.69, 1.94) | 0.58 | ||

| Parkinson's disease | 0.96 (0.17, 5.50) | 0.96 | ||

| Arthritis and other joint diseases | 1.42 (0.81, 2.51) | 0.22 | ||

| Depression | 1.95 (0.88, 4.32) | 0.10 | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 1.34 (0.73, 2.44) | 0.35 | ||

| Drug use | Use/no use (95% CI) | Dose–response‡ (95% CI) | ||

| Antipsychotics | *1.86 (1.24, 2.78) | 0.00 | 2.21 (0.89, 5.48) | 0.09 |

| Anxiolytics | 1.28 (0.78, 2.10) | 0.33 | 1.40 (0.85, 2.33) | 0.19 |

| Hypnotics or sedatives | *2.10 (1.19, 3.68) | 0.01 | *2.79 (1.13, 6.91) | 0.03 |

| Antidepressants | *2.77 (1.68, 4.57) | 0.00 | *2.96 (1.94, 4.53) | 0.00 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 1.35 (0.19, 9.65) | 0.77 | 0.23 (0.00, 70.38) | 0.62 |

| Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors | *2.74 (1.63, 4.62) | 0.00 | *3.00 (1.95, 4.62) | 0.00 |

| Other antidepressants | 1.35 (0.39, 4.73) | 0.64 | 1.10 (0.49, 2.49) | 0.81 |

| Antihypertensives | 1.39 (0.79, 2.47) | 0.26 | 1.15 (0.91, 1.46) | 0.25 |

| Anti-arrythmics | 1.22 (0.59, 2.55) | 0.59 | 1.23 (0.51, 2.98) | 0.65 |

| Nitrates and other vasodilators | 0.84 (0.22, 3.22) | 0.80 | 1.31 (0.54, 3.15) | 0.55 |

| Digoxin | 0.87 (0.21, 3.58) | 0.84 | 0.77 (0.02, 28.58) | 0.89 |

| β-adrenoceptor blocker eye drops | 1.68 (0.23, 12.30) | 0.61 | 1.17 (0.03, 39.71) | 0.93 |

| Analgesics | 1.45 (0.48, 4.36) | 0.50 | 1.17 (0.96, 1.43) | 0.11 |

| Antihistamines | 0.63 (0.19, 2.12) | 0.46 | 0.91 (0.43, 1.92) | 0.80 |

| Drugs used in diabetes | 0.95 (0.34, 2.65) | 0.92 | 1.00 (0.56, 1.78) | 1.00 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. All estimates are adjusted for gender and age.

Significant parameters.

HR per year.

HR for increase with 1 DDD.

Table 3.

Multivariate hazard ratios for injurious falls

| HR for injurious falls (95% CI) | P | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | (ns) 1.20 (0.71, 2.04) | 0.50 | ||

| Female | ref | |||

| Age* | 1.05 (1.01, 1.09) | 0.01 | ||

| Drug use | Use/no use (95% CI) | Dose–response† (95% CI) | ||

| Antipsychotics | 1.76 (1.18, 2.63) | 0.01 | ||

| Hypnotics or sedatives | (NS) 1.69 (0.96, 2.98) | 0.07 | 2.55 (1.03, 6.30) | 0.04 |

| Antidepressants | 2.58 (1.57, 4.24) | 0.00 | 2.97 (1.95, 4.53) | 0.00 |

| Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors | 2.50 (1.50, 4.19) | 0.00 | 2.98 (1.94, 4.57) | 0.00 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NS, not significant.

HR for age (continuous variable) HR per year.

HR for increase with 1 DDD.

Dose–response relationships with injurious fall risk

Significant dose–response relationships were found for the use of hypnotics or sedatives (HR 2.55, 95% CI 1.03, 6.30) and antidepressants (HR 2.97, 95% CI 1.95, 4.53). Analysis of subgroups of antidepressants showed that only the dose–response relationship for the use of SSRIs (HR 2.98, 95% CI 1.94, 4.57) remained significant.

Table 4 shows the probability of an injurious fall in percentages per day for various doses of SSRIs and hypnotics or sedatives, and for various combinations of SSRIs with hypnotics or sedatives. The figures in Table 4 stand for absolute risk. A priori we do not know which resident it concerns. Therefore, we predicted the probability to experience an injurious fall for a person with average characteristics, except for age and gender. Absolute risks are stratified at age 80 and 85 years for a male and a female resident. Increases in the absolute risk of an injurious fall for various combinations of doses of a SSRI with a hypnotic or sedative were found for both males and females, for different ages.

Table 4.

Absolute risk of an injurious fall per day for the use of SSRIs and hypnotics or sedatives

| Absolute risk of an injurious fall | No SSRIs | 0.25 DDD SSRIs | 0.50 DDD SSRIs | 1.00 DDD SSRIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No co-prescribed hypnotics or sedatives | ||||

| p(f,80) (95% CI) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.14) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.18) | 0.16 (0.11, 0.24) | 0.28 (0.17, 0.45) |

| p(m,80) (95% CI) | 0.13 (0.07, 0.17) | 0.17 (0.10, 0.22) | 0.22 (0.13, 0.29) | 0.38 (0.20, 0.55) |

| p(f,85) (95% CI) | 0.12 (0.08, 0.17) | 0.15 (0.11, 0.22) | 0.20 (0.14, 0.29) | 0.35 (0.22, 0.56) |

| p(m,85) (95% CI) | 0.16 (0.09, 0.22) | 0.21 (0.12, 0.28) | 0.28 (0.15, 0.38) | 0.48 (0.24, 0.72) |

| Increase in absolute risk of an injurious fall* | ref | 31% | 73% | 198% |

| Absolute risk of an injurious fall | No SSRIs | 0.25 DDD SSRIs | 0.50 DDD SSRIs | 1.00 DDD SSRIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.50 DDD hypnotics or sedatives | ||||

| p(f,80) (95% CI) | 0.15 (0.09, 0.25) | 0.20 (0.12, 0.33) | 0.26 (0.15, 0.43) | 0.44 (0.25, 0.80) |

| p(m,80) (95% CI) | 0.20 (0.10, 0.30) | 0.27 (0.14, 0.39) | 0.35 (0.18,0.51) | 0.61 (0.29, 0.96) |

| p(f,85) (95% CI) | 0.19 (0.11, 0.31) | 0.25 (0.15, 0.40) | 0.32 (0.20, 0.53) | 0.56 (0.31, 0.99) |

| p(m,85) (95% CI) | 0.26 (0.13, 0.38) | 0.34 (0.17, 0.50) | 0.44 (0.22, 0.66) | 0.76 (0.35, 1.23) |

| Increase in absolute risk of an injurious fall* | 59% | 109% | 174% | 373% |

| Absolute risk of an injurious fall | No SSRIs | 0.25 DDD SSRIs | 0.50 DDD SSRIs | 1.00 DDD SSRIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00 DDD hypnotics or sedatives | ||||

| p(f,80) (95% CI) | 0.24 (0.10, 0.58) | 0.31 (0.13, 0.76) | 0.41 (0.17, 1.00) | 0.71 (0.28, 1.80) |

| p(m,80) (95% CI) | 0.33 (0.12, 0.68) | 0.43 (0.15, 0.89) | 0.56 (0.20, 1.17) | 0.97 (0.33, 2.11) |

| p(f,85) (95% CI) | 0.30 (0.12, 0.72) | 0.39 (0.16, 0.94) | 0.51 (0.21, 1.23) | 0.88 (0.35, 2.22) |

| p(m,85) (95% CI) | 0.41 (0.14, 0.86) | 0.53 (0.19, 1.13) | 0.70 (0.25, 1.49) | 1.21 (0.41, 2.69) |

| Increase in absolute risk of an injurious fall* | 152% | 232% | 336% | 651% |

DDD, Defined Daily Dose; p(f,80), absolute risk of an injurious fall in percentages per day for females aged 80 years; p(m,80), absolute risk of an injurious fall in percentages per day for males aged 80 years; p(f,85), absolute risk of an injurious fall in percentages per day for females aged 85 years; p(m,85), absolute risk of an injurious fall in percentages per day for males aged 85 years. hypnotics or sedatives (N05C); SSRIs (N05AB).

The increase in absolute risk of an injurious fall is relative to a person of any age taking no SSRIs and no sedatives or hypnotics.

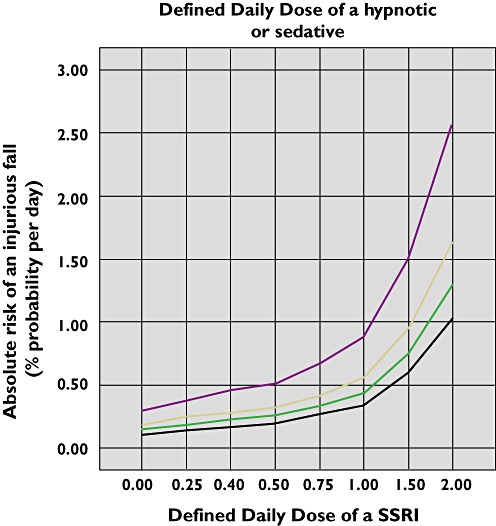

As an example from Table 4, a female resident aged 85 years, who used no SSRI or hypnotic or sedative, had an absolute risk of an injurious fall of 0.12%. Compared with nonuse, a dosage of 0.25 DDD of a SSRI increased her absolute risk of an injurious fall by 31% (absolute risk per day from P = 0.12% to P = 0.15%). A dosage of 0.5 DDD of a SSRI increased the absolute risk of an injurious fall by 73% (absolute risk per day from P = 0.12% to P = 0.20%). A dosage of 1.00 DDD of a SSRI, which was the most prevalent dose (n = 8438 person-days, 9.9% of all person-days), increased the absolute risk of an injurious fall by 198% (absolute risk per day from P = 0.12% to P = 0.35%). A combination of 1.00 DDD of a SSRI and 0.50 DDD of a hypnotic or sedative increased the absolute risk of an injurious fall by 373% (absolute risk per day from P = 0.12% to P = 0.56%). Figure 1 shows the increase in absolute risk of an injurious fall of this female resident.

Figure 1.

Absolute risk of an injurious fall (% per day) for a female resident aged 85 years by SSRI Defined Daily Dose and co-prescribed hypnotic or sedative Defined Daily Dose. None ( ); 0.25 (

); 0.25 ( ); 0.50 (

); 0.50 ( ); 1.00 (

); 1.00 ( )

)

Discussion

The main finding of this study in nursing home residents with dementia is that there is a dose–response relationship between the use of a SSRIs and a fall with a subsequent injury. The risk of an injurious fall increased with increasing doses of SSRIs. The combination of a SSRI with a hypnotic or sedative increased the risk even further.

Strength and limitations of this study

The main strength of this study is that data on medication use were collected for each day of the study period. Therefore, no misclassification was induced by the use of baseline measurement of drug use. This type of misclassification has been shown to increase with the length of a study period [32]. Another strength of this study is the fact that there was no selection bias. All eligible residents participated in the study. Furthermore, all falls were recorded by the nursing staff regardless of the type of drugs a resident might have taken, so there was no registration bias. However, as the outcome measure was injurious falls rather than falls, it might be possible that residents with depression were more likely to have their falls recorded as injurious (e.g. appear to be more distressed, take longer to get up, etc.) and were also more likely to use a SSRI. This might have led to an overestimation of our results.

Confounding by indication may be a limitation to our study. The differences in patient characteristics, which are related to the use of a SSRI and the occurrence of an injurious fall, are probably difficult to adjust for [33]. First, the underlying depression rather than the use of a SSRI might have caused the fall [34]. However, in a study which was adequately controlled for confounding by indication by restricting the analysis to antidepressant users, SSRI users still had an increased risk of a fracture [14].

Another potential limitation concerns the possible cytochrome P450 interactions. Some SSRIs are moderate to strong inhibitors of certain cytochrome P450 enzymes, notably paroxetine (strong inhibitor of CYP2D6), fluvoxamine (strong inhibitor of CYP1A2 and weaker inhibitor of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4), sertraline (moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6) and citalopram (weak inhibitor of CYP2D6). Thus it is certainly a possibility that the presence of SSRIs causes pharmacokinetic inhibition of the metabolism of other co-prescribed drugs. Therefore co-prescribed FRIDs such as benzodiazepines (CYP 3A4 substrates), antihypertensives (CYP2D6 and 3A4 substrates) and antipsychotics (CYP2D6, 3A4, 1A2 substrates and others) might have had higher plasma concentrations than in the absence of SSRIs [24]. Previous research in old age psychiatry inpatients has shown that CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 interactions involving a SSRI as an inhibitor are common in old age psychiatry inpatients [35]. These interactions may have been present in our study population, but were not the focus of the current study.

Third, neuropsychiatric symptoms and behavioural disturbances, like agitation and aggressive behaviour, for which SSRIs are recommended in dementia patients [36], may themselves lead to an increased fall risk and may result in higher drug doses. We were not able to control for this type of confounding by indication since there was no standard procedure in place to quantify and record neuropsychiatric symptoms and behavioural disturbances in the medical charts. However, recent studies have shown that behavioural and neuropsychiatric symptoms as measured with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Nursing Home version (NPI–NH) [37], [38] are very common in nursing home patients with dementia stage 5 or 6 on the GDS [18], with more than 80% showing at least one clinically relevant symptom [39], [40]. Since all residents in the study population were nursing home residents with dementia stage 5 or 6 on the GDS [18], they were all likely to have neuropsychiatric symptoms and behavioural disturbances fitting with these stages of dementia, which may reduce confounding by indication.

Fourth, a recent meta-analysis illustrated that SSRIs are heterogenous in their receptor affinities and vary widely on some side effect issues [41]. We did not analyze inter-SSRI differences. This might be another potential limitation of our study.

Another potential limitation might be that our study is from a single institution. In our study there were no users of fluoxetine or escitalopram, which are widely prescribed in many countries [41]. However, we think that our results are generalizable, because the high prevalence of antidepressant prescriptions in our study is comparable with both Dutch and international studies in nursing home settings [8], [9].

Our findings are consistent with earlier studies on the use of SSRIs and injurious falls [12], [15], [42]. However, one of these earlier studies was done in a mixed nursing home population (residents with dementia and residents without dementia), and did not investigate the dose–response relationship [12]. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study which assessed the dose–response relationship between SSRIs and injurious fall risk in nursing home residents with dementia. Another study on the risk of fractures with SSRI use found a significant dose–response relationship for the risk of a fracture, but it was done in the general population (mean age 43.4 years, SD 27.4) [15], [42]. We found an increased dose-dependent risk for injurious falls, but not for fractures. However, it is possible that with a larger sample or longer observations, we might have found a dose-dependent relationship for fractures. The increased fracture risk of SSRIs that was found in other studies may be linked to their effect on the serotonin transporter system [15].

It has been shown that users of SSRIs have a 2.35-fold (95% CI 1.23, 3.50) increased risk of a fracture, which further increased with prolonged use [14]. Moreover, in general, it has not been shown that higher doses are more effective in the treatment of depressive symptoms [43]. Furthermore, there is a paucity of studies on the efficacy of SSRIs in the treatment of depression in patients with dementia, and on the correlation between SSRI dose and effect in this specific population. Available evidence offers only weak support to the contention that SSRIs are an effective treatment for patients with depression and dementia [44]. Further studies in patients with dementia and depression are needed. Given that they may produce serious side effects clinicians should prescribe SSRIs with due caution to nursing home residents with dementia and depression.

In conclusion, even at low doses, SSRIs are associated with increased risk of an injurious fall in nursing home residents with dementia. Higher doses, which were most prevalent in our study population, increased the risk further, with a three-fold risk at 1.00 DDD. The use of a SSRI in combination with a hypnotic or sedative further increased the risk. The results of this study lend support to the consideration that new treatment protocols might be needed which take into account the dose–response relationship between SSRIs and injurious falls.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sawadi Huisman for her assistance with the data collection and reading the data in the computer.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heinze C, Halfens RJ, Dassen T. Falls in German in-patients and residents over 65 years of age. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:495–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Robbins AS. Falls in the nursing home. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:442–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-6-199409150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nurmi I, Luthje P. Incidence and costs of falls and fall injuries among elderly in institutional care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2002;20:118–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijcks BP, Neyens JC, Schols JM, van Haastregt JC, de Witte LP. Falls in nursing homes: on average almost two per bed per year, resulting in a fracture in 1.3. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005;149:1043–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neyens JC, Dijcks BP, Twisk J, Schols JM, van Haastregt JC, van den Heuvel WJ. A multifactorial intervention for the prevention of falls in psychogeriatric nursing home patients, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) Age Ageing. 2009;38:194–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CBO, Dutch Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Guideline for Prevention of Fall Incidents in Old Age. Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications BV; 2004. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, Robinson RG. The construct of minor and major depression in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2086–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann E, Kopke S, Haastert B, Pitkala K, Meyer G. Psychotropic medication use among nursing home residents in Austria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijk RM, Zuidema SU, Koopmans RT. Prevalence and correlates of psychotropic drug use in Dutch nursing-home patients with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:485–93. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishtala PS, McLachlan AJ, Bell JS, Chen TF. Determinants of antidepressant medication prescribing in elderly residents of aged care homes in Australia: a retrospective study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:210–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2716–24. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arfken CL, Wilson JG, Aronson SM. Retrospective review of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and falling in older nursing home residents. Int Psychogeriatr. 2001;13:85–91. doi: 10.1017/s1041610201007487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards JB, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Joseph L, Whitson HE, Prior JC, Goltzman D. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on the risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:188–94. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziere G, Dieleman JP, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, Pols HA, Stricker BH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibiting antidepressants are associated with an increased risk of nonvertebral fractures. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:411–7. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31817e0ecb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other antidepressants and risk of fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:92–101. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterke CS, Verhagen AP, van Beeck EF, van der Cammen TJ. The influence of drug use on fall incidents among nursing home residents: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:890–910. doi: 10.1017/S104161020800714X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-VI-TR) 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:30–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Velde N, Stricker BH, Pols HA, van der Cammen TJ. Risk of falls after withdrawal of fall-risk-increasing drugs: a prospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:232–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, Marra CA. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1952–60. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. 2002. Available at http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index (last accessed 20 August 2005)

- 24.Flockhart DA. Drug interactions: cytochrome P450 drug interaction table. Indiana University School of Medicine. 2007. Available at http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/table.aspx (last accessed 21 April 2011)

- 25.American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tromp AM, Pluijm SM, Smit JH, Deeg DJ, Bouter LM, Lips P. Fall-risk screening test: a prospective study on predictors for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:837–44. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellogg International Work Group on the prevention of falls by the Elderly. The prevention of falls in later life. A report of the Kellogg International Work Group on the Prevention of Falls by the Elderly. Dan Med Bull. 1987;34(Suppl. 4):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arcares, inter-branch organization nursing homes and care homes. Incidence Registration System (MIC) Utrecht: Arcares; 2002. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- 29.LPZ Project Group. The Dutch National Prevalence Survey of Care Problems (LPZ) Maastricht: Department of Health Care and Nursing Sciences; 2008. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna: 2008. Available at http://www.R-project.org/ (last accessed 7 October 2010)

- 31.Bates D, Maechler M, Dai B. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999375-28. 2008. Available at http://lme4.r-forge.r-project.org/ (last accessed 7 October 2010)

- 32.Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Misclassification of current benzodiazepine exposure by use of a single baseline measurement and its effects upon studies of injuries. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:663–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziere G, Dieleman JP, van der Cammen TJ, Stricker BH. Association between SSRI use and fractures and the effect of confounding by indication. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2369–70. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2369-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whooley MA, Kip KE, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Nevitt MC, Browner WS. Depression, falls, and risk of fracture in older women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:484–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies SJ, Eayrs S, Pratt P, Lennard MS. Potential for drug interactions involving cytochromes P450 2D6 and 3A4 on general adult and functional elderly psychiatric wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:464–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CBO, Dutch Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Guideline for Diagnostics and Drug Treatment of Dementia. Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications BV; 2005. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood S, Cummings JL, Hsu MA, Barclay T, Wheatley MV, Yarema KT, Schnelle JF. The use of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in nursing home residents. Characterization and measurement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8:75–83. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuidema SU, Derksen E, Verhey FRJ, Koopmans RTCM. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in a large sample of Dutch nursing home patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:632–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuidema SU, de Jonghe JFM, Verhey FRJ, Koopmans RTCM. Predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients: influence of gender and dementia severity. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:1079–86. doi: 10.1002/gps.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serretti A, Mandelli L. Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1259–72. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05346blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, neuroleptics and the risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:807–16. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen RA, Moore CG, Dusetzina SB, Leinwand BI, Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN. Controlling for drug dose in systematic review and meta-analysis: a case study of the effect of antidepressant dose. Med Decis Making. 2009;29:91–103. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08323298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bains J, Birks JS, Dening TR. The efficacy of antidepressants in the treatment of depression in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD003944. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]