Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells that are being clinically explored as regenerative therapeutics. Cultured MSCs secrete various modulatory factors, which contribute to the immunosuppressive effects of transplanted MSCs as a therapy. Although the in vitro phenotype of MSCs has been well characterized, identification of MSCs in vivo is made difficult by the lack of specific markers. Current advances in murine MSC research provide valuable tools for studying the localization and function of MSCs in vivo. Recent findings suggest that MSCs exert diverse functions depending on tissue context and physiological conditions. This review focuses on bone marrow MSCs and their roles in haematopoiesis and immune responses.

Keywords: cell trafficking, haematopoiesis, immune response, immunotherapy, mesenchymal stem cells, monocyte

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were first described in the 1960s and 1970s by Friedenstein et al.1 as a multipotent population of non-haematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. These cells are adherent and exhibit fibroblast-like morphology in culture dishes. They can differentiate into bone, cartilage, adipose tissue and fibrous tissues in vitro or in vivo after transplantation. Although the original concept of MSCs was proposed in the context of bone marrow, later studies extended the concept to multipotent cells isolated from various postnatal connective tissues, such as synovium, adipose tissue and dental pulp.2 The application of the term ‘MSC’ to these cells from diverse sources is still an issue of controversy so this review uses a restricted definition and only focuses on bone marrow MSCs.

Definition of MSCs

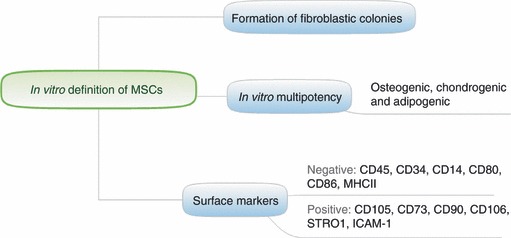

Historically, bone marrow MSCs were defined by their properties in culture. They are isolated based on their adherence on plastic dishes, which is a different feature from haematopoietic cells, and their formation of fibroblastic colonies. The multi-lineage potential of these colonies is examined under culture conditions that induce cell differentiation. Most of the phenotypic analysis of MSCs was performed on these in vitro-expanded progeny of bone marrow cells. Although MSCs cultured in vitro lack a unique marker and are probably a heterogeneous population, there is a consensus that they do not express haematopoietic markers, such as CD45, CD34 and CD14, but that they are positive for CD105, CD73 and CD90.3 The expression level of these markers can vary based on the culture conditions. Proteomic approaches are also pursued to achieve a better definition of MSCs.4 Some criteria for MSCs in vitro are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

In vitro characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).

Phenotypic characterization of MSCs in vivo has been challenging, although progress has been made in the recent decade. In humans, using monoclonal antibodies against surface marker STRO1 and CD106, Simmons et al.5 were able to isolate MSCs directly from the bone marrow. In mice, Méndez-Ferrer et al.6 identified a Nestin-expressing MSC population (Nestin+ MSCs) that is closely associated with haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Using a Nestin-GFP reporter mouse, the study demonstrated that the entire mesenchymal activity and clonogenicity of bone marrow CD45− cells reside within the Nestin+ subset. The Nestin+ MSCs are tightly associated with sinusoidal endothelium and have similar morphology to vascular pericytes. This is the first study that has identified murine bone marrow MSCs with a signal marker. The Nestin reporter provides a valuable tool with which to study MSCs in situ. Although Nestin+ MSCs share some similarity with a population of bipotent adipo-osteogenic progenitors termed CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells,7,8 i.e. both being tightly associated with sinusoidal endothelium and having extended cellular processes, the relationship between these cells remains unclear.

Function of MSCs

Residing in the bone marrow, the MSC is one of the stromal cells that can physically interact with immune cells and their progenitors. In the following, we will discuss the roles of MSCs in supporting haematopoiesis and regulating the traffic of bone marrow cells. Additionally, as many studies are focused on therapeutic use of MSCs, the effect of transplanted MSCs on immune cells will also be reviewed.

Forming the haematopoietic microenvironment

The immune system is derived from HSCs in the bone marrow. It has been proposed that HSCs reside in a confined and distinct microenvironment, termed niche.9 Those niches comprise non-haematopoietic cells that provide soluble factors and extracellular matrix to support the expansion and activity of HSCs.10 Osteoblast, which lines the bone surface at the endosteum, is a crucial component of the niche and has regulatory roles at many stages of haematopoietic development.11 As bone marrow MSCs can differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes and reticular cells,12 they are believed to be precursors of these cells in the bone marrow and thereby contribute to the formation of the haematopoietic microenvironment.

Besides the endosteal niche, many HSCs are also found in regions adjacent to sinusoidal blood vessels in the bone marrow.13 These HSCs are in close proximity to the newly described Nestin+ MSCs and CAR cells,6,7 both of which express HSC-regulatory factors. The MSCs promote survival and proliferation of HSCs in mixed culture ex vivo,14 so it has been proposed that MSCs directly interact with HSCs in vivo. Selective depletion of Nestin+ MSCs or CAR cells had a direct impact on HSC numbers and homeostasis,6,8 suggesting that MSCs themselves, independent of their progenies, are a component of the HSC niche.

Modulating the activity of immune cells

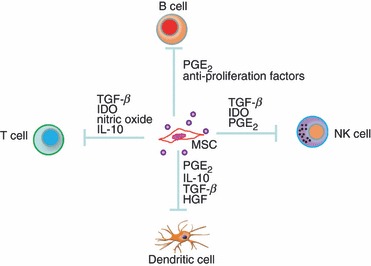

Immunomodulatory function of MSCs has been proposed because human MSCs (hMSCs) inhibit the proliferation and activation of T cells in vitro.15–17 The inhibition is not MHC restricted, and is largely mediated by secreted factors, such as transforming growth factor-β, prostaglandin E2, hepatocyte growth factor, nitric oxide and interleukin-10.18 The hMSCs also inhibit B-cell proliferation in vitro.19,20 Additionally, in mixed culture hMSCs inhibit the maturation of monocytes into dendritic cells,21–23 and suppress the pro-inflammatory potential and antigen presentation function of dendritic cells.21,24,25 Human MSCs attenuate the activation of neutrophils in vitro by inhibiting respiratory burst.26 They also suppress the proliferation of natural killer cells, and restrain their cytotoxic activity.27–29 Given the numerous reports, it seems that hMSCs down-regulate the activities of most, if not all, immune cells in vitro (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Cultured mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) suppress the proliferation and activity of immune cells by secreting soluble factors. HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IDO, indolamine dioxygenase; IL-10, interleukin-10; NK, natural killer; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

The immunomodulatory effects of MSCs are also indicated in animal models, where MSCs are infused to treat pathogenic inflammations. In mice, MSC infusion has been demonstrated to effectively ameliorate autoimmune disorders, including experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,30 diabetes31,32 and autoimmune bowl disease.33,34 Infusion of MSC also prolongs the life of a transplanted skin graft in baboons.35 In humans, an immunosuppressive effect of infused MSCs has been reported in acute, severe graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) of a 9-year-old child;36 however, subsequent trials of MSC-based therapies for treating adult GVHD failed to show a significant improvement in mortality.37 The inconsistency of MSCs’ efficacy in preventing GVHD has been observed in pre-clinical studies.38 The reasons for this varied efficacy remained unclear because of the incomplete understanding of the mechanisms by which MSCs suppress immune responses. It has been suggested that transplanted MSCs exert their function mainly through secreting soluble mediators, given the fact that there is little evidence showing the engraftment of MSCs after infusion, and that the immunosuppressive effect can be recapitulated by administration of MSC-secreted factors alone.37 The ability of MSCs to produce these factors can be affected by the procedures to isolate the population and expand it ex vivo before transplantation. This might explain the variation in difference studies. Future investigation is needed to identify the secreted factors that are essential for the therapeutic effect of MSCs for a specific disease.

It is important to note that most of the studies showing immunomodulatory effects of MSCs were performed on cultured MSCs or transplanted MSCs that had been expanded in vitro. Those results might not reflect the physiological function of MSCs in vivo. It is possible that the immunological property of MSCs is altered by culture conditions. It remains unclear whether MSCs are immunosuppressive in vivo during homeostatic states or during infection. The MSCs express functional Toll-like receptors (TLRs),39 which recognize pathogen-associated molecules and other danger signals. Treating MSCs with TLR ligands alters the proliferation, differentiation and migration of the MSCs and their secretion of chemokines and cytokines,39,40 with outcomes depending on the nature and context of TLR stimulation. For example, TLR2 and TLR4 ligands enhance the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, whereas TLR3 ligand inhibits it.41 Human MSCs primed with TLR4 produce pro-inflammatory mediators, whereas TLR3-primed hMSCs express mostly immunosuppressive ones.42 It has also been shown that MSCs lose the ability to inhibit T-cell proliferation after triggering of certain TLRs.43 Therefore, it is possible that stimuli from pathogen-associated molecules during infection can reverse the suppressive feature of MSCs or even skew their function toward promoting immune responses. Indeed, a recent study suggests that MSCs are a critical component of the innate immune system, being able to directly sense the TLR ligands in the circulation and contribute to host defence by promoting the recruitment of immune cells.44 Additionally, MSCs can function as antigen-presenting cells when primed at a low level of interferon-γ, indicating a protective role against infection in the early stage of the immune response; however, their antigen-presenting function is progressively lost as interferon-γ concentrations increase.45 This suggests a mechanism that switches the function of MSCs from immunostimulatory to immunosuppressive during the course of infection. The effect of MSCs on the immune system is therefore likely to be context-dependent.

A hurdle in studying the physiological role of MSCs in vivo is the lack of genetic or pharmacological tools that allow for gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies. The work by Méndez-Ferrer et al.6 and Omatsu et al.8 has demonstrated that MSCs can be identified, with reasonable specificity, by the expression of a single gene and genetic approaches can be used to deplete those MSCs in vivo. It would be interesting to test whether depletion of MSCs in homeostatic conditions will break immune tolerance given the suppressive effects of MSCs.

Regulating cell trafficking

Cultured MSCs constitutively secret a wide range of chemokines, including CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL7, CCL20, CCL26, CX3CL1, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, CXCL8, CXCL10, CXCL11 and CXCL12.18 The receptors for these chemokines are expressed by immune cells as well as their precursors. It is possible that by secreting chemokines MSCs regulate cell trafficking. Studies, which involve the transplantation of MSCs as a regenerative therapy, have suggested that injected MSCs home to the site of tissue injury and continue to express some of the chemokines. Monocytes and macrophages might thereby be attracted and contribute to wound healing. However, it is unclear whether the expression of chemokines by cultured MSCs is a consequence of in vitro activation or the use of specific culture conditions.

The expression of chemokines by MSCs in vivo has not been well characterized, because of the lack of markers to identify them. Recent study, which identified MSCs as Nestin+ cells associated with HSCs at the perivascular sites in the bone marrow,6 has shed light on the issue. Nestin+ MSCs express high levels of CXCL12, a chemokine that regulates the migration of HSCs. CXCL12 binds to CXCR4 and provides a signal to retain HSCs in the bone marrow.46 It has been observed that a small number of HSCs continuously exit to the bloodstream during a haemostatic state.47,48 Circulating HSCs survey peripheral tissues and replenish peripheral haematopoietic cells through in situ differentiation, and some of them eventually home to the bone marrow.49 The release of HSCs into the bloodstream is negatively correlated with the expression of CXCL12 in the bone marrow and is regulated by clock-controlled signals transmitted from the brain to the bone marrow via the sympathetic nervous system.50 Nestin+ MSCs, which are enriched in CXCL12 expression and can directly respond to signals from the sympathetic nervous system, are proposed to regulate the trafficking of HSCs. Indeed, depletion of Nestin+ MSCs leads to increased HSC egress and reduced homing of haematopoietic progenitors to the bone marrow.6

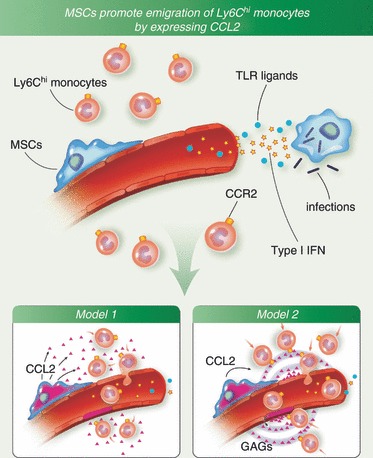

Mesenchymal stem cells also regulate the trafficking of immune cells in the bone marrow. A recent study on monocyte recruitment provides some insights.44 Ly6Chi monocytes are a subset of circulating monocytes that are essential for host defence against a variety of infections.51 They are generated in the bone marrow, and can be rapidly recruited to the peripheral tissues during infection or an inflammatory response. The release of Ly6Chi monocytes from the bone marrow is mediated by CCR2, which responds to chemokine CCL2. Local production of CCL2 in the bone marrow can be induced by circulating TLR ligands. Using CCL2 reporter mice, CCL2-expressing cells were identified at the perivascular sites with morphology similar to pericytes. These cells seem to attract monocytes to the abluminal aspect of the endothelium where they subsequently gain access to the circulation. Ex vivo characterization of these CCL2-expressing cells has revealed their ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes, indicating that CCL2-expressing cells in the bone marrow are MSCs. These cells express TLRs, and they are enriched in CXCL12. Taking advantage of the fact that bone marrow MSCs are Nestin+, CCL2 was specifically deleted from MSCs using Nestin-Cre. The deletion of CCL2 from MSCs resulted in diminished monocyte emigration from the bone marrow, and consequently an impaired immune response against infection.44 This study has demonstrated that bone marrow MSCs can detect microbial products in the circulation and orchestrate innate immune responses by promoting the emigration of monocytes (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with the fact that MSCs express TLRs and CCL2 in vitro. This is the first in vivo study showing that MSCs are a relevant source of CCL2 in the bone marrow and control the emigration of immune cells.

Figure 3.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) promote emigration of Ly6Chi monocytes from the bone marrow following infection. MSC responds to circulating Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands and secrete CCL2. Two models are proposed for the emigration of monocytes following CCL2 expression by MSCs. In the first model, CCL2 production in the bone marrow increases monocyte chemokinesis, thereby increasing the likelihood that monocytes will come into contact with blood vessels and subsequently cross the fenestrated endothelium. In the second model, CCL2 produced in proximity to vascular sinuses binds to glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and forms a chemokine gradient, which attracts monocytes to the abluminal aspect of the endothelium and further guides their transmigration into the circulation. IFN, interferon.

The observation that MSCs produce pro-inflammatory chemokines appears to be contradictory to their immunosuppressive effects. However, the ability of MSCs to secrete CCL2 together with other immunomodulatory factors actually provides a unique advantage for MSCs to orchestrate an immune response in the bone marrow. During infection, immune cells, such as monocytes, are recruited to sites of infection and become activated in the peripheral tissues. The activated monocytes not only control infection but also cause tissue damage. As the bone marrow is rarely a site harbouring infectious pathogens, the destructive activity of immune cells there should be kept in check. It is speculated that MSCs, which are located in close proximity to the sinusoid, attract monocytes to the abluminal aspect of the endothelium by expressing CCL2, and, at the same time, secret regulatory cytokines to suppress the activity of these cells temporally before they traffic to infection sites. It can be expected that these features might have different consequences when MSCs are found in the periphery or when they are infused into the circulation and subsequently home to injured tissues. For instance, instead of promoting recruitment, intravenously infused murine MSCs inhibit the migration of activated DCs from subcutaneous sites to the draining lymph nodes, probably by suppressing the up-regulation of molecules involved in dendritic cell trafficking.52 Therefore, the effect of MSCs on cell trafficking is also likely to dependent on the tissue context.

Additionally, studies have reported that mononuclear phagocytes play a role in retaining HSCs in the bone marrow,53–55 probably by regulating the expression of retention signals, such as CXCL12, in MSCs. Depletion of mononuclear phagocytes reduces the CXCL12 production by cells in niches and induces HSC mobilization.54 These studies place MSC in the centre of a regulatory network that controls the trafficking of bone marrow cells. Given the cross-talk among MSCs, monocytes and HSCs, it can be hypothesized that bone marrow mononuclear phagocytes, some of which are in the vicinity of Nestin+ MSCs, promote the expression of CXCL12 in MSCs, and thereby help to retain HSCs in the bone marrow during a static state; but during infection, MSCs facilitate the emigration of monocytes from the bone marrow by secreting CCL2. The subsequent depletion of monocytes from the bone marrow decreases the production of CXCL12 from the niches, leading to mobilization of HSCs. In this model, coordinated exits of monocytes and HSCs during the immune response are achieved through their interaction with MSCs. Indeed, infections increase the number of HSCs in the circulation.49,56 These mobilized HSCs may replenish immune cells by differentiation in the peripheral tissues,57 so it can be speculated that the cross-talk among MSCs, monocytes and HSCs promotes immune responses in the periphery against invading pathogens.

Conclusions

Mesenchymal stem cells possess the potential for multi-lineage differentiation and ability to secrete immunomodulatory factors. These properties have been explored for the development of MSC transplantation as a regenerative therapy. Advances in murine MSC research provide in vivo markers to study the localization and function of MSCs in physiological conditions. Using these tools, recent studies have demonstrated that MSCs form a perivascular niche for HSCs and regulate the trafficking of HSCs and immune cells. They are versatile in producing cytokines and chemokines, which can be either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory. The in vivo function of MSCs probably depends on tissue context and stimuli they have experienced. Deciphering the role of MSCs is important to understand the entire picture of the immune response and to better harness the therapeutic potential of MSCs.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, Frolova GP. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6:230–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianco P, Robey PG, Simmons PJ. Mesenchymal stem cells: revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:313–19. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–17. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maurer MH. Proteomic definitions of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2011;2011:704256. doi: 10.4061/2011/704256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons PJ, Torok-Storb B. Identification of stromal cell precursors in human bone marrow by a novel monoclonal antibody, STRO-1. Blood. 1991;78:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–34. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12–CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25:977–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Kondoh G, Fujii N, Kohno K, Nagasawa T. The essential functions of adipo-osteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell niche. Immunity. 2010;33:387–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams GB, Scadden DT. The hematopoietic stem cell in its place. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:333–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Xie T. Stem cell niche: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:605–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrett RW, Emerson SG. Bone and blood vessels: the hard and the soft of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:503–6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedenstein AJ, Piatetzky S, II, Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;16:381–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, Terhorst C, Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dexter TM, Allen TD, Lajtha LG. Conditions controlling the proliferation of haemopoietic stem cells in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1977;91:335–44. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040910303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, Grisanti S, Gianni AM. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99:3838–43. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Blanc K, Tammik L, Sundberg B, Haynesworth SE, Ringden O. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57:11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, Scott D, Laylor R, Simpson E, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003;101:3722–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meirelles Lda S, Fontes AM, Covas DT, Caplan AI. Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;6:419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glennie S, Soeiro I, Dyson PJ, Lam EW, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce division arrest anergy of activated T cells. Blood. 2005;105:2821–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107:367–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang XX, Zhang Y, Liu B, Zhang SX, Wu Y, Yu XD, Mao N. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit differentiation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2005;105:4120–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nauta AJ, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink E, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit generation and function of both CD34+-derived and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:2080–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramasamy R. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit dendritic cell differentiation and function by preventing entry into the cell cycle. Transplantation. 2007;83:71–6. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000244572.24780.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105:1815–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyth S, Borovsky Z, Mevorach D, Liebergall M, Gazit Z, Aslan H, Galun E, Rachmilewitz J. Human mesenchymal stem cells alter antigen-presenting cell maturation and induce T-cell unresponsiveness. Blood. 2005;105:2214–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raffaghello L, Bianchi G, Bertolotto M, Montecucco F, Busca A, Dallegri F, Ottonello L, Pistoia V. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit neutrophil apoptosis: a model for neutrophil preservation in the bone marrow niche. Stem Cells. 2008;26:151–62. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2008;111:1327–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poggi A, Prevosto C, Massaro AM, et al. Interaction between human NK cells and bone marrow stromal cells induces NK cell triggering: role of NKp30 and NKG2D receptors. J Immunol. 2005;175:6352–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zappia E, Casazza S, Pedemonte E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood. 2005;106:1755–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urban VS. Mesenchymal stem cells cooperate with bone marrow cells in therapy of diabetes. Stem Cells. 2008;26:244–53. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiorina P, Jurewicz M, Augello A, et al. Immunomodulatory function of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in experimental autoimmune type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2009;183:993–1004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko IK, Kim BG, Awadallah A, Mikulan J, Lin P, Letterio JJ, Dennis JE. Targeting improves MSC treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1365–72. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez-Rey E, Anderson P, Gonzalez MA, Rico L, Buscher D, Delgado M. Human adult stem cells derived from adipose tissue protect against experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut. 2009;58:929–39. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.168534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Gotherstrom C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, Ringden O. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parekkadan B, Milwid JM. Mesenchymal stem cells as therapeutics. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2010;12:87–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolar J, Villeneuve P, Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells for graft-versus-host disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:257–62. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pevsner-Fischer M, Morad V, Cohen-Sfady M, Rousso-Noori L, Zanin-Zhorov A, Cohen S, Cohen IR, Zipori D. Toll-like receptors and their ligands control mesenchymal stem cell functions. Blood. 2007;109:1422–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomchuck SL, Zwezdaryk KJ, Coffelt SB, Waterman RS, Danka ES, Scandurro AB. Toll-like receptors on human mesenchymal stem cells drive their migration and immunomodulating responses. Stem Cells. 2008;26:99–107. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwa ChoH, Bae YC, Jung JS. Role of Toll-like receptors on human adipose-derived stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2744–52. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waterman RS, Tomchuck SL, Henkle SL, Betancourt AM. A new mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liotta F, Angeli R, Cosmi L, et al. Toll-like receptors 3 and 4 are expressed by human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and can inhibit their T-cell modulatory activity by impairing Notch signaling. Stem Cells. 2008;26:279–89. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi C, Jia T, Méndez-Ferrer S, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells induce monocyte emigration in response to circulating toll-like receptor ligands. Immunity. 2011;34:590–601. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan JL, Tang KC, Patel AP, Bonilla LM, Pierobon N, Ponzio NM, Rameshwar P. Antigen-presenting property of mesenchymal stem cells occurs during a narrow window at low levels of interferon-gamma. Blood. 2006;107:4817–24. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1307–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright DE, Wagers AJ, Gulati AP, Johnson FL, Weissman IL. Physiological migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Science. 2001;294:1933–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1064081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abkowitz JL, Robinson AE, Kale S, Long MW, Chen J. Mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells during homeostasis and after cytokine exposure. Blood. 2003;102:1249–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, et al. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131:994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Méndez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:762–74. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiesa S, Morbelli S, Morando S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells impair in vivo T-cell priming by dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17384–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103650108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkler IG, Sims NA, Pettit AR, et al. Bone marrow macrophages maintain hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niches and their depletion mobilizes HSCs. Blood. 2010;116:4815–28. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chow A, Lucas D, Hidalgo A, et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J Exp Med. 2011;208:261–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christopher MJ, Rao M, Liu F, Woloszynek JR, Link DC. Expression of the G-CSF receptor in monocytic cells is sufficient to mediate hematopoietic progenitor mobilization by G-CSF in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:251–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee HM, Wu W, Wysoczynski M, Liu R, Zuba-Surma EK, Kucia M, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Impaired mobilization of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in C5-deficient mice supports the pivotal involvement of innate immunity in this process and reveals novel promobilization effects of granulocytes. Leukemia. 2009;23:2052–62. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.King KY, Goodell MA. Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:685–92. doi: 10.1038/nri3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]