Abstract

The genus Mycobacterium comprises major human pathogens such as the causative agent of tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), and many environmental species. Tuberculosis claims ∼1.5 million lives every year, and drug resistant strains of Mtb are rapidly emerging. To aid the development of new tuberculosis drugs, major efforts are currently under way to determine crystal structures of Mtb drug targets and proteins involved in pathogenicity. However, a major obstacle to obtaining crystal structures is the generation of well-diffracting crystals. Proteins from thermophiles can have better crystallization and diffraction properties than proteins from mesophiles, but their sequences and structures are often divergent. Here, we establish a thermophilic mycobacterial model organism, Mycobacterium thermoresistibile (Mth), for the study of Mtb proteins. Mth tolerates higher temperatures than Mtb or other environmental mycobacteria such as M. smegmatis. Mth proteins are on average more soluble than Mtb proteins, and comparison of the crystal structures of two pairs of orthologous proteins reveals nearly identical folds, indicating that Mth structures provide good surrogates for Mtb structures. This study introduces a thermophile as a source of protein for the study of a closely related human pathogen and marks a new approach to solving challenging mycobacterial protein structures.

Keywords: M. tuberculosis, M. thermoresistibile, crystallography, thermophile

Introduction

Tuberculosis remains a main cause of death from infectious diseases, but Mtb pathogenesis is still poorly understood. Structural biology is an integral part of efforts to understand Mtb biology and to develop novel drugs,1 but many Mtb proteins remain intractable to crystallization and structure determination. One method for obtaining crystals from proteins that are refractory to crystallization is the use of homologs from thermophiles.2 Thermophiles have evolved to maintain protein function in extreme temperatures, and thermal stability of proteins, in turn, can translate into better crystallization and diffraction properties.2

Thermal stability of proteins is not well understood, but involves all levels of protein structure.3 Thus, the engineering of more stable proteins is impractical on a large scale, making native sources of evolutionarily-selected thermostable proteomes invaluable. Because of their divergence from mesophiles, however, structures from thermophiles often provide information only about the general fold of orthologs of interest, limiting their use for applications such as structure-guided drug development that require more detailed information.

Human pathogens constitute only a small group within the Mycobacterium genus, whereas most mycobacteria are environmental bacteria that are better adapted to survive high temperatures than obligate pathogens. Mth is an environmental, non-tubercular mycobacterium that was isolated from soil in 1966.4 It was named for its growth at 52°C, indicating higher temperature tolerance than Mtb. Although an environmental bacterium, Mth can opportunistically infect immunocompromised patients, and cause granuloma formation in the lung.5,6 The unique combination of thermoresistance and similar pathogenicity makes Mth a particularly useful model organism for Mtb.

Here, we introduce Mth as a source for Mtb protein orthologs with higher solubility and potentially better stability and crystallization properties that are yet similar enough to infer detailed information about their Mtb counterparts.

Results and Discussion

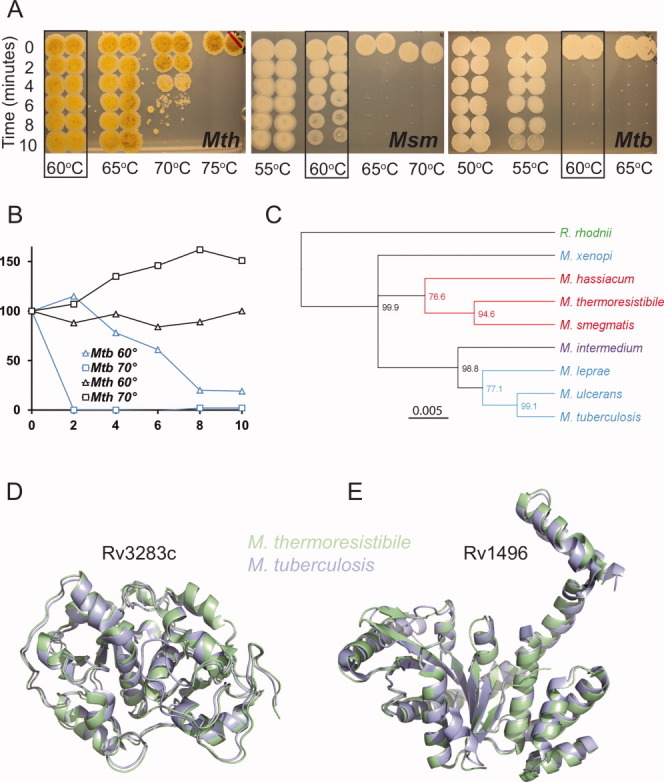

To directly compare Mth and Mtb and to further define the limits of Mth heat resistance, we tested growth, metabolic activity, and survival of Mth and Mtb over a range of temperatures [Fig. 1(A)]. Mtb tolerated only a very narrow temperature range, with growth ceasing at 39°C. Mth growth, in contrast, was still optimal at 50°C (data not shown).4 The colony forming units assay showed killing of Mtb at 55°C, whereas Mth could withstand heating to 70°C for several minutes. The alamarBlue assay as a measure of cellular reducing potential confirmed these phenotypes, with loss of signal at 60°C for Mtb after a 10 min heat shock, but no loss of signal even at 70°C for Mth. Heat resistance of another environmental mycobacterium, M. smegmatis, was intermediate, with loss of colony forming units beginning at 60°C, and complete killing at 65°C [Fig. 1(B)].

Figure 1.

Mth is more heat-resistant than Mtb and Mth and Mtb structures are highly similar. A: Mth survives heating to 70°C for short periods, as shown by cfu assay. Mtb begins to lose viability at 55°C and is killed at 60°C. Msm shows intermediate heat resistance. Boxes indicate survival at 60°C. Mth shows characteristic yellow pigmentation. B: Metabolic activity as measured by alamarBlue assay shows disappearance of reducing potential in Mtb after 10 min heat shock at 60°C, whereas Mth is not affected even at 70°C. One representative of at least three independent experiments is shown. C: Phylogenetic tree of eight Mycobacterium 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequences. Sequences were aligned with the outgroup sequence from shared suborder Rhodococcus rhodnii. The unrooted HKY UPGMA tree is based on 1475 aligned nucleotide positions of the 16S rRNA gene, and bootstrap consensus percentages over 50% are shown at the nodes. Branch color represents growth rate, where blue is slow, red is rapid, purple is intermediate. Green denotes non-mycobacterial. D: Superposition of the sulfurtransferase SseA (Rv3283) and E: RAS superfamily GTPase (Rv1496) with their Mth orthologs shows almost identical folds.

A phylogenetic analysis of Mth 16S rRNA shows that Mth clusters with the fast growing M. smegmatis [Fig. 1(C)]. Although Mth is more closely related to M. smegmatis than Mtb, the genome size of 4.87 Mb is more similar to Mtb (4.4 Mb) than M. smegmatis (7 Mb). The similar genome size suggests that Mth can provide a complete set of Mtb orthologs. The Mth genome sequence is now available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Accession number NZ_AGVE00000000.1) and provides a resource for recombinant expression of all Mth orthologs. For initial expression and structural analysis, we identified 110 Mth orthologs from a set of 183 Mtb proteins from DrugBank (http://www.drugbank.ca). The amino acid identity between these proteins ranged between 20% and 92%, with an average of 60%. To compare solubility of recombinant Mth and Mtb proteins, we determined the number of soluble proteins obtained from a partly overlapping sample set. Seventy-six percent of the Mth targets were soluble (n = 56) when expressed in E. coli, compared to 66% of Mtb proteins (n = 126). This difference in solubility was also apparent comparing direct orthologs, with 10% more soluble proteins obtained from Mth (n = 45). This comparison is likely to underestimate the solubility of Mth proteins because some well-soluble proteins that had already been obtained from Mtb were excluded.

To structurally compare orthologs of Mtb and Mth, we solved the crystal structures of Rv3283 and Rv1496 and their Mth orthologs. A sequence alignment of Mtb Rv3283 and Rv1496 to their Mth orthologs by BLAST shows 80% (79%) sequence identity and 89% (90%) sequence similarity between the Mth and Mtb proteins. The structures of Rv3283 and its Mth ortholog have an overall Cα RMSD of 0.75 Å, showing almost identical overall fold [Fig. 1(D)]. For the second structural pair, Rv1496 and its Mth ortholog, the structures agree within an RMSD of 1.1 Å [Fig. 1(E)]. The structures of Rv3283 and its ortholog were solved at a resolution of 2.1 Å, but the Mth structure could be refined to a lower Rcryst/Rfree and had a lower average B-value of 21.7 Å2 compared to 33.7 Å2 (Supporting Information Table 1). For the Rv1496 and Mth ortholog structural pair, we also observed a higher B-factor for the Mtb structure (46) than for the Mth structure (37) at comparable resolution (data not shown). The B-factor is a measure of a crystal's thermal motion and could indicate better ordering of the Mth crystals. The RAS superfamily GTPase Rv1496 was solved bound to GDP for both Mtb and Mth and all residues that contact the product dinucleotide were conserved across both species.

Many Mtb proteins, for example RpoB, the target of the first line drug rifampicin, and EmbB, the target of ethambutol, have proven refractory to crystallization, calling for novel approaches to solve challenging structures. Mth is an environmental mycobacterium identified from soil, but also an opportunistic human pathogen that can cause granuloma formation in the lung,5,6 a hallmark of Mtb infection. These observations suggest that while primarily an environmental mycobacterium with some evolutionary distance from the Mtb complex, Mth can serve as a model organism that is likely to recapitulate certain aspects of Mtb pathogenesis. Despite these similarities, Mth has adapted to withstand higher temperatures than the obligate pathogen Mtb. Although thermoresistance provides advantages for protein crystallization, proteins from extremophiles are inevitably more diverged from their mesophile orthologs, limiting their use for detailed structural understanding of a protein. Mth reconciles the trade-off between similarity to the human pathogen Mtb and thermoresistance.

Although larger datasets will be required to comprehensively determine the benefits of Mth orthologs for crystallization, our initial analysis points towards several advantages. Mth proteins were on average more amenable to recombinant soluble expression than Mtb proteins. The Mth ortholog of Rv3283 crystallized much more readily than the Mtb protein, and Mth crystallographic parameters were consistent with better crystal packing. In the case of a nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase, the Mth ortholog was the only one of 21 homologs from eight mycobacterial species that produced diffracting crystals.7 The structural comparison of the Mth and Mtb orthologs of Rv3283 and Rv1496 shows that Mtb and Mth structures are indeed highly similar, indicating that detailed structural information about Mtb proteins can be inferred from their Mth orthologs.

In summary, we establish the thermophile Mth as a model system for obtaining Mtb protein structures, adding a new tool for solving challenging mycobacterial structures.

Materials and Methods

Growth of cultures and heat shock treatment

Mth was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Stationary cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.2 in temperature-equilibrated 7H9 medium and incubated at the indicated temperatures in a thermocycler. At each time point, sample in duplicate was placed on ice. To assess viability, heat-treated samples were spotted on a 7H10 plate for cfu determination. For alamarBlue assay, 10 μL of alamarBlue reagent was added to 90 μL sample and incubated at 37°C for 3 h.

Sequencing, target selection, protein expression, and purification

The Mth sequences were obtained from a preliminary Mth genome sequence generated by Illumina paired-end sequencing. Targets for recombinant expression were selected by a BLASTP sequence similarity search with the Mtb target proteins against GLIMMER-predicted Mth ORFs. Additional targets were identified by searching for M. smegmatis homologs of the targets by BLASTN and analysis of matching Mth ORFs with the EMBOSS getorf tool. A BLASTP protein similarity search of the 280 retrieved M. smegmatis targets against the predicted Mth ORFs yielded 129 additional targets. Incomplete sequences were removed to yield a final set of 110 Mth targets. Genes were cloned, expressed, and protein purified as recently described.8

Crystallization, data collection, and structure determination

Proteins (36.6 mg/mL for Mtb Rv3283 or 48.2 mg/mL for Mth Rv3283 ortholog) were crystallized at 16°C with an equal volume of precipitant against reservoir (80 μL) in sitting drop vapor diffusion format. Mtb crystals grew in 2.4M ammonium sulfate, 0.1M BisTris pH 6.5. Mth crystals grew in 8% PEG 4000 and 0.1M NaOAc pH 4.6. The Mtb and Mth crystals were harvested, cryoprotected in precipitant with 15–20% ethylene glycol, and vitrified in liquid nitrogen. Data were collected at 100 K, reduced, and the structures solved by molecular replacement with Phaser,9 using the Thermus thermophilus rhodanese structure (1UAR) as a search model for the Mtb structure, and the Mtb structure as the search model for the Mth structure. The final models were obtained by refinement in REFMAC10 and manual building in COOT.11 Structures were validated using Molprobity.12 Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 3P3A, 3HZU, 3MD0, and 3TK1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the whole Seattle Structural Genomics Consortium for Infectious Diseases (SSGCID) team and the beamline staff at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab Advanced Light Source. They thank Thomas Ioerger for helpful discussions, and Malcolm Gardner and members of the Seattle Biomedical Research Institute's Bioinformatics core for help with sequence assembly and analysis.

Supplementary material

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of the article.

References

- 1.Musa TL, Ioerger TR, Sacchettini JC. The tuberculosis structural genomics consortium: a structural genomics approach to drug discovery. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2009;77:41–76. doi: 10.1016/S1876-1623(09)77003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenney FE, Jr, Adams MW. The impact of extremophiles on structural genomics (and vice versa) Extremophiles. 2008;12:39–50. doi: 10.1007/s00792-007-0087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakravarty S, Varadarajan R. Elucidation of factors responsible for enhanced thermal stability of proteins: a structural genomics based study. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8152–8161. doi: 10.1021/bi025523t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukamura M. Adansonian classification of mycobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;45:253–273. doi: 10.1099/00221287-45-2-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu F, Andrews D, Wright DN. Mycobacterium thermoresistibile infection in an immunocompromised host. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:546–547. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.4.546-547.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weitzman I, Osadczyi D, Corrado ML, Karp D. Mycobacterium thermoresistibile: a new pathogen for humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:593–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.5.593-595.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Edwards TE, Begley DW, Abramov A, Thompkins KB, Ferrell M, Guo WJ, Phan I, Olsen C, Napuli A, Sankaran B, Stacy R, Van Voorhis WC, Stewart LJ, Myler PJ. Structure of nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase component B from Mycobacterium thermoresistibile. Acta Cryst. 2011;F67:1100–1105. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111012541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryan CM, Bhandari J, Napuli AJ, Leibly DJ, Choi R, Kelley A, Van Voorhis WC, Edwards TE, Stewart LJ. High-throughput protein production and purification at the Seattle structural genomics center for infectious disease. Acta Cryst. 2011;F67:1010–1014. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111018367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Cryst. 1997;D53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Cryst. 2010;D66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.