Abstract

The present study examined school-based racial and gender discrimination experiences among African American adolescents in Grade 8 (n = 204 girls; n = 209 boys). A primary goal was exploring gender variation in frequency of both types of discrimination and associations of discrimination with academic and psychological functioning among girls and boys. Girls and boys did not vary in reported racial discrimination frequency, but boys reported more gender discrimination experiences. Multiple regression analyses within gender groups indicated that among girls and boys, racial discrimination and gender discrimination predicted higher depressive symptoms and school importance and racial discrimination predicted self-esteem. Racial and gender discrimination were also negatively associated with grade point average among boys but were not significantly associated in girls’ analyses. Significant gender discrimination X racial discrimination interactions resulted in the girls’ models predicting psychological outcomes and in boys’ models predicting academic achievement. Taken together, findings suggest the importance of considering gender- and race-related experiences in understanding academic and psychological adjustment among African American adolescents.

Keywords: Race, Gender, Discrimination, African American, Adolescence

While African American girls and boys face many similar challenges in their academic environments, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting gender, in addition to race, figures prominently in their educational and psychological development. African American girls and boys may experience different treatment as a function of both their race and their gender and be affected by these experiences in different ways (e.g., Noguera 2003; Oyserman and Harrison 1998). To understand optimal development for racial and ethnic minority youth, it is important to consider the varied racial- and gender-related influences on their adjustment (e.g., García Coll et al. 1996; Spencer et al. 1997). However, few studies examine both race and gender discrimination among youth of color. The current study served as an explicit examination of school-based racial discrimination and gender discrimination experiences among African American adolescents. One goal was to consider whether African American girls and boys varied in school-based discrimination experiences they attributed to race and to gender. A second goal was to take a within-gender approach in examining associations of gender and race discrimination on youths’ academic and psychological adjustment. Taking this approach allowed us to consider frameworks focused on relative advantage and disadvantage between African American girls and boys and also move beyond group comparisons to consider variation in the frequency of discrimination experiences as well as implications for academic and psychological adjustment.

Racial and Gender Discrimination among African Americans: Competing Frameworks

The current paper considers several conceptual frameworks that address the relative risk of experiencing discrimination among racial/ethnic minority females and males. According to the double jeopardy hypothesis, Black females face double marginalization given their membership in two traditionally lower status social minority groups (women and Blacks), making them targets of both racism and sexism (e.g., Beal 1970; Reid and Comas-Diaz 1990). Alternatively, a double jeopardy perspective has been applied to Black males, for example in scholarship deriving from social dominance theory (e.g., Sidanius et al. 2004). This perspective posits that in hierarchical societies, racism is more severely targeted toward subordinate males, who are more likely than females to be viewed as threats to dominant structures. In this case, Black males are framed as being at greater risk of experiencing discrimination than females (Sidanius and Veniegas 2000). The ethnic-prominence hypothesis suggests racial/ethnic minority individuals are likely to focus on their racial/ethnic membership rather than their gender membership when making judgments about discriminatory experiences, given the historical and contemporary salience of race in the United States (Levin et al. 2002). This raises possibilities that Black females and males would experience similar levels of racial discrimination and lower gender discrimination relative to racial discrimination.

There is a dearth of empirical development around race and gender discrimination among African Americans that address the above perspectives and even less examination among adolescents. Furthermore, despite documented gender differences in school outcomes among African American youth, there is little analysis of race and gender processes in school settings that may underlie these differences (e.g., Chavous and Cogburn 2007; Frazier-Kouassi 2002; Thomas and Stevenson 2009).

Racial Discrimination Experiences of African American Girls and Boys

Racial discrimination is a relevant and important risk factor in African American adolescents’ everyday lives (e.g., McLoyd and Steinberg 1998; Fisher et al. 2000; Romero and Roberts 1998; Sellers et al. 2006). Researchers have established that even infrequent or minor occurrences of racial discrimination may result in diminished psychological well-being (Klonoff and Landrine 1995), lowered self-esteem (King 2003), and higher depressive symptoms, anger, problem behaviors, and psychiatric symptoms (e.g., Fisher et al. 2000; Greene et al. 2006; Sanders-Phillips 2009), as well as lower academic motivation and achievement (e.g., Chavous et al. 2008; Wong et al. 2003).

Educational and psychological literatures suggest African American males (both adults and adolescents) are at greater risk than African American females for experiencing racial discrimination (e.g., Noguera 2003; Sidanius and Veniegas 2000). This is partly attributable to gendered racial stereotypes, e.g., of Black boys being perceived as aggressive and physically threatening (e.g., Greene et al. 2006). These perceptions may contribute to African American males being targets of race-based discrimination, particularly more punitive forms of racial discrimination, such as being disciplined more harshly than other youth (e.g., Skiba et al. 2002). Additionally, racial socialization research suggests African American parents are more likely to emphasize racial barrier messages with boys, raising the possibility of boys’ increased likelihood of perceiving racial discrimination (Chavous et al. 2008). Empirical evidence of gender variation in African American adolescents’ racial discrimination experiences is somewhat mixed. For instance, in a late adolescent sample, Sellers and Shelton (2003) found that males reported racial discrimination more frequently than females but did not find this difference in a later study using a sample of mid-adolescents (Sellers et al. 2006). Other studies suggest gender variation in racial discrimination experiences among African American adolescents depend on factors such as social class (Chavous et al. 2008).

Gender Matters, Too: Gender Discrimination as an Adolescent Risk Factor

Gender and its relationship to social roles and expectations in US society significantly impact individuals’ life experiences and circumstances (Reid and Comas-Diaz 1990), and a considerable body of scholarship has also considered gender influences on educational development (e.g., Meece and Eccles 1993). Existing research provides evidence that gender discrimination negatively impacts an array of physical, psychological, and personal factors, such as lowered self-esteem, depression, and restricted occupational aspirations (e.g., Brown et al. 2010; Klonoff, Landrine and Campbell 2000; Ro and Choi 2009; Schmitt et al. 2007). Gender discrimination experiences have also been shown to be a unique predictor of stress (Moradi and Subich 2003), distinct from other non-gender-specific stressors (e.g., Klonoff et al. 2000).

Generally, research suggests that females experience more gender discrimination than do males (e.g., Schmitt et al. 2007). Settles et al. (2008) contend that gender is devalued and associated with low status for all women, finding similarity in women’s reports of gender discrimination across ethnic groups. An adolescent study by Brown et al. (2010) found that boys were less likely than girls to attribute actions to gender discrimination. They suggested that girls have a greater awareness of their lower social status and in turn have a greater sensitivity for discriminatory treatment based on gender. Even among African American women, for whom race likely holds personal significance, gender and gendered experiences can be identified as being distinct from experiences based on other social categories (Reid and Comas-Diaz 1990; Settles et al. 2008).

Most research focused on gender bias and discrimination, however, has excluded youth of color. The ways that gender matters for African American youth may differ from norms established with majority samples. For example, with regard to the current study focus on school-based experiences, educational research conducted with White Americans indicates boys are more likely to be viewed as intellectual in comparison to girls (e.g., Beyer 1999). However, African Americans boys are often perceived more negatively than African American girls in terms of intellectual capability (e.g., Noguera 2003). Higher achievement is also often with higher status in academic settings, which would suggest that African American girls may hold more social power than boys given their relatively higher achievement (Fordham 1993; Chavous and Cogburn 2007). It is unclear, then, how African American girls and boys are experiencing their classroom treatment in terms of gender status, which may have implications for their perceptions of gender discriminatory treatment.

Also, there is evidence of gender differences in response to gender discrimination, with more negative psychological impacts for women relative to men (e.g., Schmitt et al. 2007). These differences have been attributed to men holding a more privileged societal status that protects them from the negative effects of gender discrimination. The lack of research including racial/ethnic samples, coupled with evidence that Black males and females may hold different social statuses (particularly within educational settings) than mainstream gender hierarchies, raises important questions about gender variation in the effect of gender discrimination among African American youth.

The Experience and Effect of Gender Discrimination and Racial Discrimination

There are few theoretical or empirical examples concurrently examining racial and gender discrimination experiences among African Americans (e.g., Woods-Giscombé and Lobel 2008) and even fewer studies focusing on African American adolescents (e.g., Dubois et al. 2002). This lack of research limits our understanding of the unique academic experiences and related consequences for African American youth.

Levin et al. (2002) examined a Black adult sample to test the double jeopardy hypothesis against an alternative position, the ethnic-prominence hypothesis. Black men and women in their sample similarly expected general discrimination, and for women, the expectation for general discrimination was more closely linked to ethnic discrimination rather than gender discrimination. It was not clear from the authors’ analyses, however, whether Black women and men varied in their experiences with ethnic and gender discrimination. In one of the few studies examining race and gender discrimination among adolescents, Dubois et al. (2002) investigated associations of race- and gender-based stressors with emotional and behavioral adjustment among Black and White early adolescents. Although within-race subgroup comparisons were not of central interest, the authors did note patterns observed across Black girls and boys. A higher percentage of Black girls (27%) reported at least one discriminatory event (racial or gender) than did Black boys (19%). It was not clear from presented analyses, however, whether the difference was statistically significant and analyses regarding the types of events (racial or gender) that were more frequent for Black girls and boys were not reported.

Beyond gender differences in the experience of discrimination, African American girls may be uniquely affected by these experiences (Chavous and Cogburn 2007; Oyserman et al. 2001), but scholarship is equivocal regarding the nature of these effects. Oyserman et al. (2001) posit that the gender socialization of girls often emphasizes the importance of approval and relationships. These messages may increase vulnerability to the effects of negative experiences with valued others (e.g., discriminatory treatment from teachers), regardless of attributions to race or gender. Researchers posit that girls’ responses to stress make them particularly vulnerable to negative psychological functioning when experiencing stressors such as discrimination. In early- and mid-adolescence, girls report more depressive symptoms in response to stress than boys (Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus 1994). This disparity has been partly attributed to internalized reactions to stress among girls, which contribute to increased anxiety and depressive symptoms (e.g., Leadbeater and Way 1996). Brody et al. (2006), however, did not find differences between girls and boys in the impact of racial discrimination on depressive symptoms among a 10–12 year old African American sample.

For boys, academic disengagement may be a common coping response to devaluing experiences in the school setting, potentially having an adverse effect on motivation and achievement (Chavous et al. 2008; Cunningham 1999; Osborne 1999; Swanson et al. 2003). Disengagement from academic domains in response to negative racial experiences may be detrimental to academic outcomes but can be protective psychologically (e.g., Spencer 1999). This suggests a greater negative impact of discrimination on boys’ academic outcomes relative to their psychological outcomes. In contrast, Black girls’ academic performance may be more protected in the face of discrimination due to their unique socialization. Racial socialization literatures suggest that African American females are particularly likely to receive messages about the utility and importance of education for mobility (e.g., Taylor et al. 1990). The emphasis on educational utility may enable girls to persist in terms of academic performance when discrimination is experienced in the academic domain. Hubbard’s (2005) interview study of Black adolescent girls suggested that their academic persistence could be attributed in part to their willingness to challenge instances of being devalued in school.

It is unclear, however, whether African American youths’ responses to racial and gender discrimination vary. Interestingly, the DuBois et al. (2002) study indicated that both racial and gender daily hassles were directly associated with general stress for Black adolescent girls but only racial hassles had a direct association for Black boys. While this finding provides evidence that gender discrimination plays a stronger role for girls in relation to psychological outcomes, more research is needed, including work focused on academic and psychological outcomes. Taken together, we know relatively little about the ways African American adolescents experience both race and gender discrimination. The literatures reviewed, however, provide insights suggesting that boys and girls may have different race-specific and gender-specific experiences, and these experiences may influence girls’ and boys’ psychosocial adjustment in different ways.

Study Aims

Previous scholarship indicates that experienced discrimination around race and gender are significant risk factors for both negative academic and psychological outcomes. Also, various literatures provide evidence that African American girls and boys respond to experienced risk around their race and gender memberships in similar and unique ways. However, there has been relatively little empirical analysis of how African American girls and boys report and are affected by racial and gender discrimination experiences. The present study investigates school-based racial and gender discrimination experiences and their relationships with psychological adjustment (depressive symptoms, self-esteem) and academic adjustment (grades, school importance) among African American 8th-grade adolescents.

In the present study, we focus on the implications of experiencing both racial discrimination and gender discrimination. According to the double jeopardy hypothesis, females of color would be more likely to experience both racial and gender discrimination, resulting in their relative disadvantage to males of color on adjustment outcomes (e.g., Reid and Comas-Diaz 1990). Social dominance perspectives argue that the globally low status of Black males and views of Black males as threatening, a consequence of both their race and gender, places them at greater risk of experiencing and being negatively impacted by multiple forms of discrimination (e.g., Sidanius and Veniegas 2000). Finally, an ethnic-prominence perspective suggests that race is more salient as a social identity to people of color in the US relative to gender, which leads to more experiences of racial discrimination relative to gender discrimination experiences. The former two perspectives imply an additive, negative influence of race and gender discrimination on adjustment, while the latter seems to suggest the driving influence of racial discrimination on adjustment.

While a number of scholars posit the higher risk of discrimination for Black boys and educational research indicates boys experience more negative school-based treatment than do girls, current scholarship is mixed with regard to whether African American males and females actually report different levels of racial discrimination, and little research considers Black youths’ experiences of their school-based interactions as gender discrimination. Finally, few studies examine both race and gender discrimination among adolescents. Thus, we sought to consider explicitly how African American youth experienced both racial and gender discrimination and the associations of both with youth adjustment. We considered the above perspectives (double jeopardy, social dominance, ethnic-prominence) by examining (1) gender variation in reported experiences of school-based racial and gender discrimination; (2) ways that racial discrimination and gender discrimination contributed uniquely to the prediction of academic and psychological adjustment among boys and girls; and (3) the interaction of racial and gender discrimination in relation to adjustment outcomes among boys and girls.

Method

Participants

This study used data from the third wave (1993; 8th grade) of the Maryland Adolescent Development in Context Study (MADICS) conducted by Eccles, Sameroff, and colleagues. MADICS data were collected between 1991 and 2000 and represent a 9-year longitudinal, community-based study of 1,480 adolescents and their families (61% African American; 35% European American). The sample was drawn from a county with diverse ecological settings (e.g., rural, low income, high risk urban neighborhoods, and middle class suburban) and is broadly representative of different SES levels. Data for the present study included a subsample of African American youth from the larger study (N = 413, 51% male). Youth were surveyed regarding their 8th-grade school year with data collection occurring between the end of 8th-grade and the 9th-grade transition to high school. The median family income was between 45,000 and 49,999, although there was substantial variation across the sample, including a sizeable African American middle class. Over half of the samples’ primary caregivers completed high school and 40% completed college. Only respondents who self-identified as African American and had complete data for all study variables were included in the following analyses. Students who had missing data did not differ in terms of gender, χ2(1, N = 413) = .07, p = .80 or socioeconomic status, t(908) = −.37, p = .71. (Detailed information about participants’ community and school contexts can be found at the study website: http://www.rcgd.isr.umich.edu/garp.)

Procedures

Data collection was conducted in the respondents’ homes, using interview and survey formats. As often as possible, race of interviewer was matched to race of the primary care giver. The target adolescent and parent were individually interviewed for approximately 1 h each, and each filled out a 45-min self-administered questionnaire. During the youth survey administrations, adolescents’ parents were present in the home during interviewers’ visits. Informed consent was obtained from both the parent and youth participants.

Measures

Discrimination

Youths’ racial discrimination experiences at school in 8th grade were assessed with a measure developed by the MADICS primary investigators consisting of two sub-scales, peer/social discrimination, and teacher/classroom discrimination. Only the teacher/classroom discrimination subscale was used in the present study. The scale included four items evaluating students’ experiences of race-based discrimination in class settings by teachers in the past year (e.g., being disciplined more harshly, graded harder, called on less, or thought of as less smart, because of race). Responses to both subscales were on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = everyday (α = .87). The measure of gender discrimination experiences was also developed by MADICS primary investigators and assessed teacher/classroom discrimination. The four items for the gender discrimination scale were identical to those in the teacher/classroom racial discrimination scale (α = .86).

Academic Adjustment

Youths’ grade point average was based on core academic subject areas (e.g., math, science, English, social studies) and was obtained from school records. Their GPAs were measured on a 5-point scale (0 = F, 1 = D, 2 = C, 3 = B, 4 = A) with averages ranging from 0 to 4.0. School importance is a three-item measure on a 5-point, Likert-type scale (Wong et al. 2003) assessing youths’ beliefs about the utility of school for future success (α = .70).

Psychological Adjustment

Our depressive symptoms measure was adapted from the Depressive Symptoms Checklist (SCL-90-R; Derogatis 1982), which was designed to assess a broad range of self-reported psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology such as hopelessness, loneliness, sadness, and suicidal thoughts (α = .72). The self-esteem measure included 5 items adapted from the global self-worth sub-scale of the Self-Perception Profile for Children (Harter 1985) (α = .82). Example items include, “How often do you wish you were different than you are” and “How happy are you with the way you act.”

Demographic and Background Variables

Several variables were included in primary analyses predicting youth outcomes to account for variation in study outcomes due to adolescent socioeconomic status and prior academic achievement. Prior academic achievement (7th grade) is a composite variable consisting of 7th-grade standardized test scores and average grade point average. Socioeconomic status is a composite variable based on information provided by the primary caregivers, including family’s annual income, highest educational level of either caregiver and highest occupational status of either caregiver (Nam and Powers 1983).

Results

Gender Differences in Study Variables

Analysis of covariance was used, including 7th-grade achievement and socioeconomic status (composite of mother’s education and family income) as covariates, to examine gender differences in study variables (see Table 1). The analysis indicated no significant difference in racial discrimination mean scores between boys (M = 1.85, SD = .97) and girls (M = 1.62, SD = .86). Boys, however, reported higher mean gender discrimination scores (M = 2.04, SD = 1.04) than did girls (M = 1.45, SD = .71). Girls had significantly higher 8th-grade academic achievement as well as higher reported depressive symptoms than boys. There were no significant differences between boys and girls in reported self-esteem or school importance.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of racial discrimination, gender discrimination academic and psychological variables, and control variables for girls and boys

| Variable | Girls

|

Boys

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Ach. (7th) | .13 | .88 | – | −.37 | .93 | – | ||||||||||||||

| SES | 1.48 | .50 | .44** | – | 1.48 | .50 | .30** | – | ||||||||||||

| Racial disc. | 1.62 | .89 | −.21** | −.08 | – | 1.88 | .97 | −.26** | −.15* | – | ||||||||||

| Gender disc. | 1.45 | .70 | −.22** | −.11 | .65** | – | 2.07 | 1.05 | −.06 | .03 | .46** | – | ||||||||

| School imp. | 4.11 | .56 | .35** | .13 | −.32** | – | ||||||||||||||

| .32** | – | 3.87 | .72 | .36** | .04 | – | ||||||||||||||

| .43** | – | .38** | – | |||||||||||||||||

| GPA. | 3.16 | .55 | .80** | .34** | −.24** | – | ||||||||||||||

| .30** | .38** | – | 2.90 | .55 | .73** | .23** | – | |||||||||||||

| .27** | −.05 | .32** | – | |||||||||||||||||

| Dep. sym. | 1.34 | .35 | −.28** | −.09 | .39** | .33** | −.17 | −.22 | – | 1.29 | .31 | −.14 | −.04 | .26** | .34** | −.33** | −.07 | – | ||

| Self-esteem | 3.85 | .92 | .16* | .08 | −.24** | −.14* | .12 | .22** | .50** | – | 4.07 | .79 | .01 | −.07 | −.30** | −.20* | .20** | .03 | −.44** | – |

Ach 7th 7th-grade academic achievement, GPA grade point average in 8th-grade, Racial and Gender Disc. racial and gender discrimination, School Imp school importance, Depressive Sym. depressive symptoms

p < .05,

p < .01

Correlations between Study Variables

Pearson’s product correlations were used to examine bivariate relationships among predictor and outcome variables for boys and girls. Analyses indicated a moderate, positive correlation between racial and gender discrimination for boys (r = .46, p < .01) and a strong positive correlation between racial and gender discrimination for girls (r = .65, p < .01). Table 1 summarizes the means, standard deviations and correlations of girls’ and boys’ samples. For both gender groups, racial and gender discrimination had a moderate, positive relationship with depressive symptoms and a negative, moderate relationship with academic achievement and school importance.

Types of Discrimination Experienced By Boys and Girls

We conducted within-gender group comparisons of girls’ and boys’ reports of racial discrimination and gender discrimination. A paired samples t test revealed a statistically reliable difference between the mean of racial discrimination for girls (M = 1.61, SD = 0.86) and boys (M = 1.85, SD = 0.97) and gender discrimination for girls (M = 1.45, SD = 0.71) and boys (M = 2.04, SD = 1.04), suggesting that both girls (t(217) = 3.89, p = .000, α = .05) and boys (t(228) = −2.40, p = .017, α = .05) reported more gender discrimination relative to racial discrimination.

To explore variation in types of discrimination girls and boys reported, we conducted analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) for each item in the two discrimination sub-scales, including 7th grade achievement and SES variables as covariates. For the racial discrimination items, boys reported higher means for being grade (M = 1.80, SD = 1.10) and disciplined more harshly (M = 1.96, SD = 1.20) than did girls (M = 1.50, SD = 0.93; M = 1.56, SD = 1.00). Boys also reported higher means for being thought of as less smart because of their race (M = 1.76, SD = 1.10) than did girls (M = 1.49, SD = 0.93). Boys and girls did not differ significantly in reports of being called on less because of race (p < .10). For the gender discrimination scale, boys reported significantly higher scores than did girls on all four items.

Racial and Gender Discrimination as Predictors of Academic and Psychological Outcomes

Hierarchical ordinary least squares regression analyses were conducted to examine relationships between race and gender-related discrimination and academic and psychological outcomes. Our interest was in taking a within-group approach, examining girls and boys as distinct populations with regard to the predictive roles of racial and gender discrimination (e.g., Roderick 2003; Swanson et al. 2003), rather than in comparing the relative strength of relationships between discrimination and adjustment outcomes across boys and girls; thus, separate models were tested for boys and girls. Racial and gender discrimination was included in the same model to capture the distinct contributions of both discrimination types on youth outcomes while also accounting for any overlapping variance. In the first block of each regression model, 7th-grade academic achievement and 8th-grade family SES were included as control variables, along with the primary predictors—8th-grade school-based racial and gender discrimination. To consider the frameworks positing the additive and multiplicative effects of racial and gender discrimination, we computed an interaction term, racial discrimination X gender discrimination and included it in the second block of each model. Higher-order interactions were examined according to procedures forwarded by Aiken and West (1991) as well as by Cohen and Cohen (1983). Accordingly, the primary predictor variables were centered before entering into models and significant interactions were plotted to interpret the nature of the relationships. For each of the significant racial discrimination X gender discrimination interactions, the plot illustrates the slope of the regression of the dependent variable regressed on racial discrimination estimated at selected conditional values (M + 1 SD and M−1 SD) of gender discrimination (Cohen and Cohen 1983).

Racial and Gender Discrimination as Predictors of Girls’ Adjustment

Depressive Symptoms

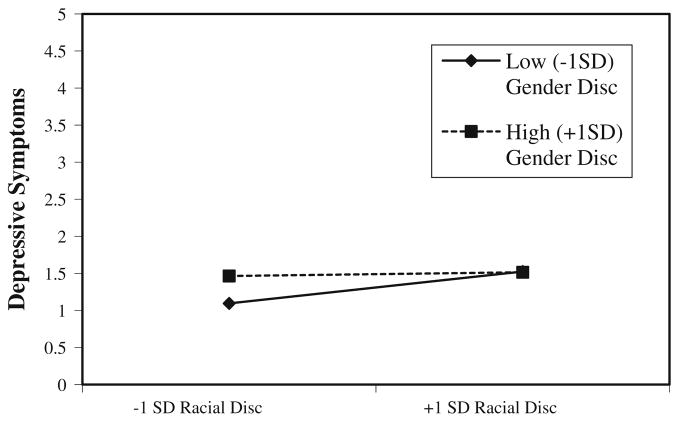

Results of racial discrimination models predicting girls’ adjustment outcomes are presented in Table 2. The depressive symptom model accounted for 18% of the variance in depressive symptoms, F(4, 203) = 12.10, p < .00. Prior academic achievement was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms for girls (β = −.21, p < .05). Higher racial discrimination scores related to higher depressive symptom scores (β = .24, p < .00) and gender discrimination showed a moderate, positive, and significant association with girls’ depressive symptoms (β = .14, p = .09). Also, we found a significant gender discrimination X racial discrimination interaction predicting depressive symptoms (β = −.21, p < .05), increasing the explained variance by 3%. For girls reporting higher gender discrimination, the relationship between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms was non-significant. However, among girls reporting lower gender discrimination, there was a significant, positive relationship between racial discrimination and depressive symptoms (see Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Summary of hierarchical regression analysis predicting girls’ academic and psychological adjustment (n = 204)

| Grade point average

|

School importance

|

Depressive symptoms

|

Self-esteem

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SEb | β | b | SEb | β | b | SEb | β | b | SEb | β | |

| 1. Family SES | .00 | .01 | .04 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .00 | .00 | .03 | .00 | .01 | .03 |

| 7th grade achievement | .43 | .04 | .70*** | .18 | .05 | .27*** | −.08 | .03 | −.21** | .11 | .08 | .11 |

| Gender discrimination | .00 | .05 | .00 | −.16 | .07 | −.20** | .07 | .04 | .14+ | .05 | .11 | .04 |

| Racial discrimination | −.01 | .04 | −.01 | −.06 | .05 | −.10 | .10 | .03 | .24** | −.26 | .09 | −.24** |

| 2. Family SES | .00 | .01 | .04 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .04 |

| 7th grade achievement | .43 | .04 | .69*** | .18 | .05 | .27*** | −.09 | .03 | −.21** | .11 | .08 | .11 |

| Gender discrimination | −.00 | .06 | −.00 | −.15 | .07 | −.18* | .12 | .04 | .25** | −.12 | .12 | −.08 |

| Racial discrimination | −.01 | .04 | −.01 | −.07 | .05 | −.10 | .09 | .03 | .23** | −.24 | .09 | −.22** |

| Gender discrimination × racial discrimination | .01 | .04 | .01 | −.03 | .05 | −.04 | −.10 | .03 | −.21** | .28 | .09 | .24** |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Fig. 1.

Girls: Gender discrimination × racial discrimination predicting depressive symptoms

Self-Esteem

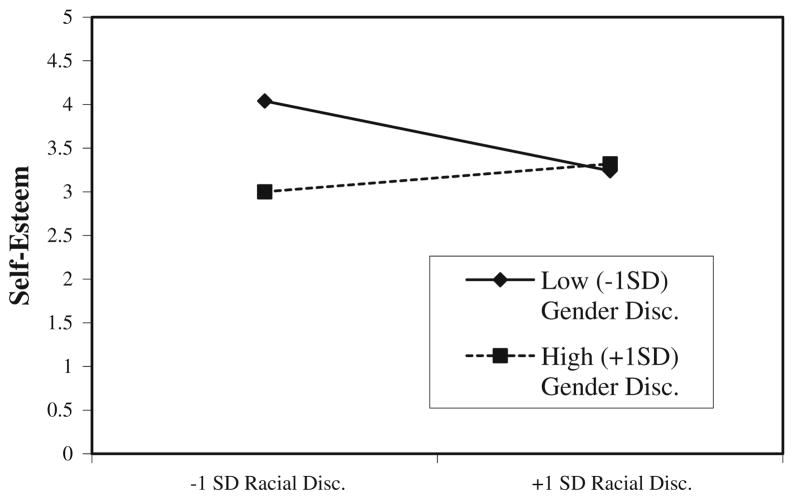

Results of the model predicting self-esteem for girls, F(4, 203) = 3.86, p < .00, are presented in Table 2. Racial discrimination was negatively related to self-esteem (β = −.26, p < .01) and was the only significant main effect in the model. A significant gender discrimination X racial discrimination resulted (β = .24, p < .01), increasing explained variance in self-esteem by 4%. Among girls reporting lower gender discrimination, racial discrimination was significantly and negatively related to self-esteem, while racial discrimination was unrelated to self-esteem among girls reporting higher gender discrimination. Of note is that girls reporting both lower racial and gender discrimination reported the highest self-esteem (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Girls: Gender discrimination × racial discrimination predicting self-esteem

School Importance

The school importance model for girls was significant, F(3, 188) = 12.96, p < .00, explaining 17% of the variance in school importance (see Table 2). Prior achievement (β = .27, p < .00) was the only significant predictor of school importance for girls.

Grade Point Average

The model predicting grade point average (GPA) among girls explained 49% of the variance in GPA, F(4, 203) = 49.30, p < .00 (see Table 2). Prior academic achievement was the only significant predictor of girls’ grades (β = .70, p < .00).

Racial and Gender Discrimination as Predictors of Boys’ Adjustment

Depressive Symptoms

Results of racial discrimination models predicting boys’ adjustment outcomes are presented in Table 3. The model predicting boys’ depressive symptoms, F(4, 208) = 8.29, p < .01, accounted for 12% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Gender discrimination (β = .26, p < .01) and racial discrimination (β = .14, p < .05) were associated with more reported depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Summary of hierarchical regression analysis predicting boys’ academic and psychological adjustment (n = 209)

| Grade point average

|

School importance

|

Depressive symptoms

|

Self-esteem

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SEb | β | b | SEb | β | b | SEb | β | b | SEb | β | |

| 1. Family SES | .01 | .01 | .11+ | −.00 | .01 | −.03 | −.00 | .00 | −.03 | −.01 | .01 | −.09 |

| 7th grade achievement | .27 | .04 | .47*** | .19 | .05 | .25*** | −.03 | .02 | −.08 | −.03 | .06 | −.04 |

| Gender discrimination | .09 | .03 | .17** | −.14 | .04 | −.20** | .08 | .02 | .26*** | −.05 | .06 | −.06 |

| Racial discrimination | −.09 | .04 | −.17** | −.20 | .05 | −.28*** | .04 | .02 | .14* | −.22 | .06 | −.27*** |

| 2. Family SES | .01 | .01 | .11+ | −.00 | .01 | −.03 | −.00 | .00 | −.04 | −.01 | .01 | −.09 |

| 7th grade achievement | .28 | .04 | .47*** | .18 | .05 | .24*** | −.03 | .02 | −.08 | −.03 | .06 | −.04 |

| Gender discrimination | .07 | .03 | .13* | −.13 | .05 | −.20** | .07 | .02 | .23** | −.03 | .06 | −.04 |

| Racial discrimination | −.13 | .04 | −.23*** | −.19 | .05 | −.27*** | .03 | .02 | .10 | −.20 | .07 | −.24** |

| Gender discrimination × racial discrimination | .09 | .03 | .17** | −.02 | .04 | −.02 | .04 | .02 | .13+ | −.06 | .06 | −.08 |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Self-Esteem

In the model predicting boys’ self-esteem, F(4, 208) = 5.13, p < .01, the model accounted for 7% of the variance. Racial discrimination (β = −.27, p < .01) was the only significant predictor of boys’ self-esteem.

School Importance

In the model predicting school importance beliefs among boys, F(3, 179) = 21.14, p < .00, 25% of the variance in beliefs was explained. There were significant main effects for prior achievement (β = .25, p < .00), gender discrimination (β = −.20, p < .05) and racial discrimination (β = −.28, p < .00).

Grade Point Average

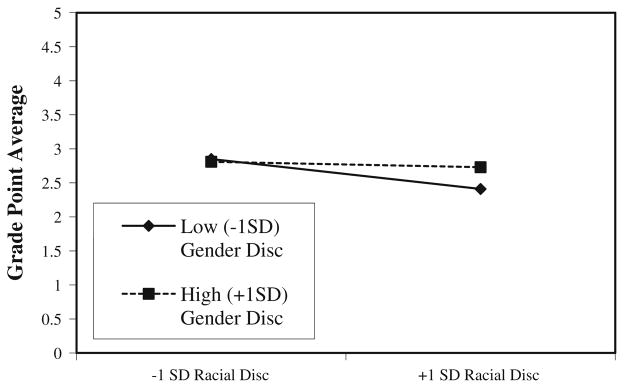

Boys’ GPA model explained 31% of variance in GPA, F(4, 208) = 24.50, p < .00. Prior achievement (β = .47, p < .01) related to higher GPAs. While racial discrimination (β = −.17, p < .01) resulted in a lower grade point average for boys, gender discrimination (β = .17, p < .01) was positively associated with grade point average. A significant interaction between gender discrimination and race discrimination resulted (β = .17, p < .01), increasing explained variance by 2%. A plot of the interaction revealed that boys had similar GPAs when reporting lower racial discrimination, regardless of gender discrimination level. There was a significant, negative association between racial discrimination and GPA among boys reporting lower gender discrimination. Among boys reporting higher gender discrimination, racial discrimination was not related to GPA (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Boys: Gender discrimination × racial discrimination predicting grade point average

Discussion

Our study focus was on understanding African American adolescents’ perceptions of both racial and gender discrimination experiences and the implications of these experiences for academic and psychological adjustment. Too little theory and research explicitly considers how processes related to both race and gender might help us to understand Black youths’ academic experiences and outcomes (Chavous and Cogburn 2007). In this study, we considered several different (and sometimes competing) social science frameworks positing variation in the experience of race and gender discrimination among African American males and females. Finally, our consideration of classroom-based discrimination reflects our view of the school context as a developmentally and socially important context within which to examine adolescents’ race- and gender-related experiences.

Perceptions of Racial and Gender Discrimination

Boys and girls in this sample reported low average frequencies on the racial or gender discrimination measure. Nonetheless, the findings provide compelling evidence that these experiences, even when infrequent, can have a significant and negative effect on important psychological and academic outcomes. Contrary to frameworks positing gender differences in racial discrimination (e.g., double jeopardy and social dominance), girls and boys did not differ in average reported frequency of racial discrimination. Thus, findings do not support prior scholarship suggesting boys’ higher likelihood of experiencing racial discrimination relative to girls (e.g., Chavous et al. 2008; Noguera 2003; Sidanius and Veniegas 2000).

Our findings also do not fully support the ethnic-prominence perspective, which suggests that members of racial/ethnic minority groups are more likely to attribute discriminatory experiences to race/ethnicity rather than to gender membership. Interestingly, boys in this sample reported more gender discrimination than did girls, and both boys and girls reported more gender discrimination relative to racial discrimination. Item-level analyses further revealed that boys, relative to girls, reported higher means on all but one racial discrimination item and for each item in the gender discrimination scale. Although research examining differential treatment in schools often focuses on boys (e.g., Cunningham et al. 2003), seldom are boys asked explicitly about their experiences with gender. These findings suggest that both boys and girls are paying attention to and are aware of their gender-based experiences as being, at least partly, distinct from their reported racial experiences. The finding that boys in the present study more frequently reported gender discrimination does not imply, however, that girls are not paying attention to or impacted by these experiences. Girls may be more likely to experience more subtle, passive discrimination (e.g., being invisible, negative non-verbal interactions) that are not captured in the present study, which focused more on punitive actions and overt behaviors (e.g., Chavous et al. 2008).

Discrimination Experiences and Academic and Psychological Functioning

Although youth reported fairly low mean frequencies of racial and gender discrimination, the experiences had a deleterious effect on academic and psychological adjustment for both girls and boys. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that even “infrequent” occurrences of discrimination can negatively impact important life outcomes (Sellers et al. 2006). Our findings also raise questions, however, about the ways in which African American girls and boys are affected by these experiences. Our literature review provided support for the expectation that among girls, discrimination would more negatively impact psychological outcomes relative to academic outcomes. This was partly supported by our findings. For girls, racial discrimination had a significant, negative association with depressive symptoms and self-esteem but did not predict academic outcomes. In contrast, gender discrimination experiences related to academic attitudes for girls (e.g., increased pessimism about the importance of school for their futures) but were not associated with academic performance or psychological outcomes. Our literature review noted that Black girls’ racial socialization might be more likely to focus on race than on gender (and is consistent with the ethnic-prominence perspective). While academic performance was not associated with discrimination, negative academic attitudes may contribute to reduced performance or educational aspirations over time. Given research demonstrating that psychological health can negatively affect educational outcomes (e.g., Joe et al. 2009), it is possible that the effects of discrimination on psychological functioning for girls also may indirectly influence performance outcomes.

For boys, we expected that discriminatory experiences would have stronger associations with academic rather than psychological outcomes. We found that both racial and gender discrimination had direct associations with boys’ academic attitudes and academic performance as well as depressive symptoms. Research suggests discrimination is particularly likely to result in conduct problems among African American boys relative to girls (Brody et al. 2006), which may contribute to boys’ poor academic and psychological outcomes (e.g., Spencer 1999). African American boys generally are overrepresented in school disciplinary action, which has implications for time out of the classroom, continuity of instruction, and ultimately academic performance (US Department of Education 1999). Thomas and Stevenson (2009) note boys’ behavioral responses to unfair treatment by teachers may reinforce stereotypes and increase the likelihood of disciplinary referrals and placement in special education (Neal et al. 2003), which may exacerbate risk of academic underachievement (e.g., Hinshaw and Lee 2003) and psychological maladjustment (Steward et al. 1998).

Our examination of the racial discrimination X gender discrimination interactions also did not fully support the double jeopardy hypothesis, as the results did not indicate a cumulative, negative effect of experiencing high levels of both discrimination types. For girls reporting higher levels of gender discrimination, there was no association of racial discrimination with depressive symptoms. For girls reporting less gender discrimination, however, racial discrimination had a deleterious association with depressive symptoms. It is of note that reporting both low racial and gender discrimination generally related to more positive psychological outcomes. The findings suggest what may be described as an inoculation effect for psychological outcomes, in that experiencing higher levels of gender discrimination buffered the negative effect of experiencing another form. In contrast, experiencing discrimination only as a function of race seemed to have the most deleterious effect on girls’ psychological outcomes.

For boys, we found an interaction of racial and gender discrimination in relation to academic performance. Similar to the girls’ patterns, the relationship between boys’ reported racial discrimination and grade point average was non-significant for boys reporting higher gender discrimination, and racial discrimination was negatively related to GPA among boys experiencing lower gender discrimination. In this case, though, boys reporting lower gender and lower racial discrimination had similar GPAs as boys reporting lower racial discrimination but higher gender discrimination. Thus, although racial and gender discrimination showed direct, negative associations with grade point average for boys, the interaction effect suggests experiencing differential treatment as race-based discrimination only may be more influential on achievement.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study helps to highlight the importance of considering experiences with both racial and gender discrimination during adolescence. Also, by including indicators of academic and psychological adjustment, we were able to consider multiple ways girls and boys may be affected by discrimination experiences in the school setting. Future research may also consider factors that may be protective or compensatory to discrimination experiences. There is a growing body of research, for instance, which suggests racial identity or the ways in which individuals interpret discriminatory experiences can serve a protective function in relation to racial discrimination (e.g., Sellers and Shelton 2003; O’Connor 2002). Similarly, race socialization research suggests that receiving messages from parents regarding group pride and self-worth may serve as protective factors in the face of racial bias and adversity (e.g., Neblett et al. 2006). Future research may also consider whether girls and boys benefit from different types of messages, given evidence that boys and girls receive difference types of socialization messages from their parents.

Measuring the distinct implications of both racial and gender discrimination for adjustment represents an important, initial step in understanding these experiences among African American youth. Our findings support that, at least to some degree, racial and gender discrimination are being identified and functioning as distinct phenomena. Taking this approach, however, we were unable to delineate whether participants are referring to the same or different experiences in their reports of discrimination. There may be some overlap in terms of what types of experiences are being referenced (Reid and Comas-Diaz 1990). Some of the youth in this sample may be referring to some of the same events in their reports of racial and gender discrimination (i.e., they are not making a clear distinction across the two types). Others, however, also may be identifying different types of experiences based distinctly on either race or gender. In addition, youth who are attuned to cues related to racial discrimination also may be more aware of gender discrimination cues and vice versa (e.g., Moradi and Subich 2003). Future research might assess specific types of experiences that youth are having and youths’ attributions as race or gender based, or both. Another limitation worthy of note is that most study measures were self-report and subject to reporting biases. Finally, the current study sample had, on average, indicators of fairly higher family socioeconomic status relative to other studies of African American youth, although there was substantial variation among the sample. Future work might examine the implications of racial and gender discrimination among youth in different ecological contexts (considering variation in socioeconomic background and neighborhood, community, school, and community contexts).

Conclusions

Despite these considerations, the present study addresses important theoretical and empirical gaps in research examining discrimination experiences of African American youth. The study adds to a growing effort to move our scholarly considerations of gender into the lives of ethnic minority youth as well as consider the unique ways race and gender processes may occur across and within African American boys and girls. Such approaches would best position researchers to address the global need for improvements in and supports for the educational and social experiences and adjustment of African American boys and girls.

Contributor Information

Courtney D. Cogburn, Email: ccogburn@umich.edu, University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, 426 Thompson Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1248, USA

Tabbye M. Chavous, University of Michigan, Combined Program in Education and Psychology, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Tiffany M. Griffin, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beal FM. Doublejeopardy: TobeBlackandfemale. In: Cade T, editor. The Black woman: An anthology. New York: Signet; 1970. pp. 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer S. Gender differences in the accuracy of grade expectancies and evaluations. Sex Roles. 1999;41(3–4):279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, et al. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Bigler R, Chu H. An experimental study of the correlates and consequences of perceiving oneself to be the target of gender discrimination. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2010;107:100–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavous T, Cogburn CD. The superinvisible woman: The study of Black women in education. Black Women, Gender & Families. 2007;1(2):24–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chavous T, Rivas D, Smalls C, Griffin T, Cogburn CD. Gender matters, too: The influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(3):637–654. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M. African American adolescent males’ perceptions of their community resources and constraints: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(5):569–589. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M, Swanson DP, Spencer MB, Dupree D. The association of physical maturation with family hassles in African American males. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:274–276. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Adolescent norms for the SCL-90R. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois D, Burk-Braxton C, Swenson L, Tevendale H, Hardesty J. Race and gender influences on adjustment in early adolescence: Investigation of an integrative model. Child Development. 2002;73(5):1573–1592. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29(6):679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham S. “Those Loud Black Girls”: (Black) women, silence and gender “Passing” in the academy. Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 1993;24I(1):3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier-Kouassi S. Race and gender at the crossroads: African American females in school. African American Research Perspectives. 2002;8(1):151–162. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for children: Revision of the perceived competence scale for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Lee SS. Conduct and oppositional defiant disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 144–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard L. The role of gender in academic achievement. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 2005;18(5):605–623. [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Joe E, Rowley LL. Consequence of physical health and mental illness risks for academic achievement in grades K-12. Review of Research in Education. 2009;33:283–309. [Google Scholar]

- King K. Do you see what I see? Effects of group consciousness on African American women’s attributions to prejudice. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff E, Landrine H. The schedule of sexist events: A measure of lifetime and recent sexist discrimination in women’s lives. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19:439–472. [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff E, Landrine H, Campbell R. Sexist discrimination may account for well-known gender differences in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24(1):93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Way N, editors. Urban Girls: Resisting stereotypes, creating identities. New York: New York University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Levin S, Sinclair S, Veniegas R, Taylor P. Perceived discrimination in the context of multiple social identities. Psychological Science. 2002;13:557–560. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meece JL, Eccles JS. Introduction: Recent trends in research on gender and education. Educational Psychologist. 1993;28(4):313–319. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Subich L. A concomitant examination of the relations of perceived racist and the sexist events to psychological distress for African American women. Counseling Psychologist. 2003;21:451–469. [Google Scholar]

- Nam C, Powers M. The socioeconomic approach to status measurement: With a GUIDE to occupational and socioeconomic status scores. Houston: Cap and Gown Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Neal LVI, McCray AD, Webb-Johnson G, Bridgest ST. The effects of African American movement styles on teachers’ perceptions and reaction. Journal of Special Education. 2003;37(1):49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett E, Philip C, Cogburn C, Sellers R. African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black psychology. 2006;32(2):199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Noguera PA. The trouble with Black boys: The role and influence of environmental and cultural factors on the academic performance of African American males. Urban Education. 2003;38(4):431–459. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C. Black women beating the odds from one generation to the next: How the changing dynamics of constraint and opportunity affect the process of educational resilience. American Eductional Research Journal. 2002;39(4):855–903. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne J. Unraveling underachievement among Afrian American boys from an identification with academics perspective. Journal of Negro Education. 1999;68(4):55–565. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Harrison K. Implications of cultural context: African American identity and possible selves. In: Swim J, Stanger C, editors. Prejudice: The target’s perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Harrison K, Bybee D. Can racial identity be promotive of academic efficacy? International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25(4):379–385. [Google Scholar]

- Reid P, Comas-Diaz L. Gender and ethnicity: Perspectives on dual status. Sex Roles. 1990;22(7/8):397–408. [Google Scholar]

- Ro AE, Choi KH. Social status correlates of reporting gender discrimination and racial discrimination among racially diverse women. Women and Health. 2009;49(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/03630240802694756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick M. What’s happening to the boys? Early high school experiences and school outcomes among African American male adolescents in Chicago. Urban Education. 2003;38(5):538–607. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural variables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1998;21(6):641–656. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K. Racial discrimination: A continuum of violence exposure for children of color. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review. 2009;12:174–195. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe N, Kobrynowicz D, Owen S. Perceiving discrimination against one’s gender group has different implications for well-being in women and men. Society for Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;28(2):197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R, Shelton N. The role of racial identity in perceived discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(5):1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Linder NC, Martin PP, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Settles I, Pratt-Hyatt J, Buchanan N. Through the lens of race: Black and white women’s perceptions of womanhood. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:454–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, Pratto F, van Laar C, Levin S. Social Dominance Theory: Its Agenda and Method. Political Psychology. 2004;25:845–880. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J, Veniegas R. Gender and race discrimination: The interactive nature of disadvantage. In: Oskamp S, editor. Reducing prejudice and discrimination. The claremont symposium on applied social psychology. Mahway, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba RJ, Michael RS, Nardo AC, Peterson RL. The color of discipline: Sources of racial and gender disproportionately in school punishment. Urban Review. 2002;34(4):317–342. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Social and cultural influences on school adjustment: The application of an identity-focused cultural ecological perspective. Educational Psychologist. 1999;34(1):43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, Hartman T. A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development & Psychopathology. 1997;9(4):817–833. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward RJ, Jo HI, Murrary D, Fitzgerald W, Neil D, Fear F, et al. Psychological adjustment and coping styles of urban African American high school students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1998;26:70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DP, Cunningham M, Spencer MB. Black males’ structural conditions, achievement patterns, normative needs and “opportunities”. Urban Education. 2003;38:605–633. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Tucker B, Lewis E. Developments in research on Black families: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52(4):993–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DE, Stevenson H. Gender risks and education: The particular classroom challenges for urban low-income African American boys. Review of Research in Education. 2009;33:160–180. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Education. Projected student suspension rates values for the nation’s public schools by race/ethnicity: Elementary and secondary school civil rights compliance reports. Washington, DC: Office of Civil Rights; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;7(6):1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL, Lobel M. Race and gender matter: A multidimensional approach to conceptualizing and measuring stress in African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(3):173–182. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]