Abstract

Platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the traditional treatment of choice for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); however, the efficacy of these regimens has reached a plateau. Increasing evidence demonstrates that patients with sensitizing mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) experience improved progression-free survival and response rates with first-line gefitinib or erlotinib therapy relative to traditional platinum-based chemotherapy, while patients with EGFR-mutation negative tumors gain greater benefit from platinum-based chemotherapy. These results highlight the importance of molecular testing prior to the initiation of first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC. Routine molecular testing of tumor samples represents an important paradigm shift in NSCLC therapy and would allow for individualized therapy in specific subsets of patients. As these and other advances in personalized treatment are integrated into everyday clinical practice, pulmonologists will play a vital role in ensuring that tumor samples of adequate quality and quantity are collected in order to perform appropriate molecular analyses to guide treatment decisions. This article provides an overview of clinical trial data supporting molecular analysis of NSCLC, describes specimen acquisition and testing methods currently in use, and discusses future directions of personalized therapy for patients with NSCLC.

Keywords: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), molecular testing, personalized medicine, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer represents the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and worldwide, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of approximately 16% for all stages [1,2]. While platinum-based doublet therapy is the traditional treatment of choice for advanced/metastatic (stage IIIB/IV) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), no specific regimen is clearly superior, and efficacy with these regimens has reached a plateau in terms of overall response rate (RR; ∼25%-35%) and median overall survival (OS; 8-10 months) [2]. Molecular testing for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations has allowed for the identification of subsets of patients who will be more responsive to certain therapies. Consequently, the treatment of patients with NSCLC is evolving toward a more personalized approach that utilizes specific molecular and genetic tumor profiles in treatment decisions. In addition to oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists, pulmonologists are essential team members in this quest for individualized treatment, playing a critical role in obtaining material for cytologic and histologic studies as well as ensuring that tissue is submitted for appropriate molecular investigation. This article reviews the clinical evidence supporting molecular typing of NSCLC, describes approaches for tissue sampling and molecular analysis, and discusses future directions of molecular profiling and the personalized treatment of patients with NSCLC.

Rationale for the Routine Testing of EGFR in NSCLC

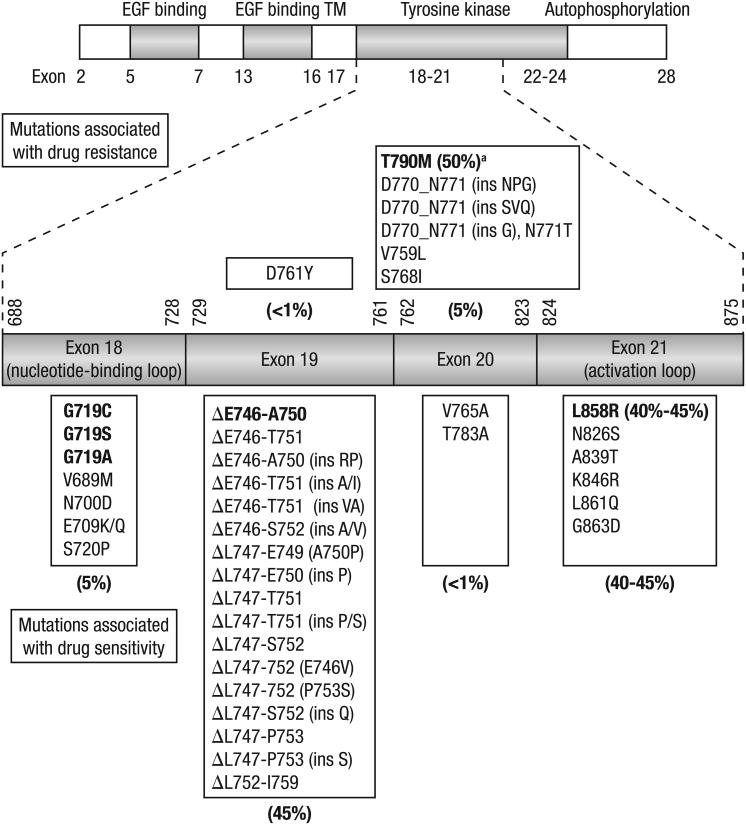

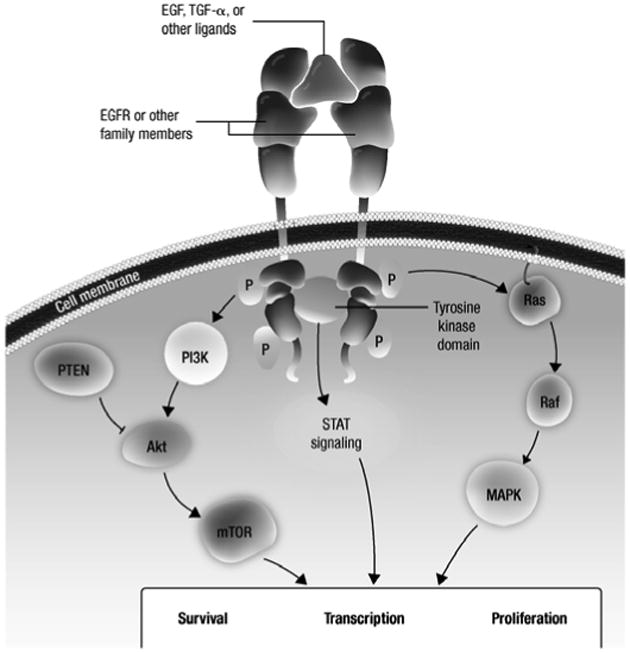

The pathologic role of the EGFR pathway in the initiation and progression of NSCLC is well established (Figure 1) [3,4]. Retrospective analyses in patients with NSCLC have reported increased EGFR expression in 40% to 80% of tumors and demonstrated a correlation between increased expression and poor prognosis [5,6]. Based on the role of EGFR in the pathogenesis of NSCLC, inhibitors of EGFR signaling have been developed as a therapeutic strategy for NSCLC, including monoclonal antibodies that block ligand binding [5] and small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Reversible EGFR TKIs, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, competitively bind to EGFR and are approved for NSCLC in various settings [7,8], while investigational irreversible EGFR TKIs (eg, afatinib [BIBW 2992], PF00299804), which target multiple human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family members simultaneously, are undergoing clinical evaluation for NSCLC. Approximately 90% of patients with genetic EGFR aberrations harbor either a 15-base pair nucleotide in-frame deletion in exon 19 (E746-A750del) or a L858R point mutation in exon 21 (Figure 2) [6,9,10]. These aberrations lead to ligand-independent constitutive activation of EGFR and have been shown to confer sensitivity to EGFR TKIs.

Figure 1. EGFR signal transduction pathways.

In response to ligand binding, members of the EGFR family of receptor tyrosine kinases form dimers and are activated, resulting in downstream signaling which promote survival and proliferation.

Akt, protein kinase B; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; P, phosphate; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; Raf, v-raf 1 murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1; Ras, retrovirus-associated DNA sequences; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; TGF, transforming growth factor.

Figure 2. Gefitinib- and erlotinib-sensitizing mutations of EGFR in NSCLC.

A cartoon representation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) showing the distribution of exons in the extracellular domain (EGF binding), transmembrane domain (TM), and intracellular domain (comprising the tyrosine kinase and autophosphorylation regions). Exons 18-21 in the tyrosine kinase region where the relevant mutations are located are expanded and a detailed list of EGFR mutations in these exons that are associated with sensitivity to gefitinib or erlotinib is shown. Percentages are denoted for some mutations and exons, and the main mutations in each class are shown in bold.

Relationship of EGFR Mutations and Response to EGFR TKIs

Early clinical studies first showed improved clinical benefit with gefitinib and erlotinib in certain patient populations, including those with adenocarcinoma, never smokers, women, and those from East Asia [11]. In the double-blind phase III ISEL study in unselected patients with relapsed/refractory NSCLC, those with EGFR mutations had higher RR than patients without EGFR mutations (37.5% vs 2.6%), but data were insufficient for survival analysis [12]. In the randomized phase III BR.21 trial [13], again in an unselected population that had relapsed/refractory disease (following at least 1 chemotherapy regimen), those who received erlotinib had a longer progression-free survival (PFS) and OS compared with placebo (P <0.001 for each). However, EGFR mutational status was not significantly associated with survival benefit with erlotinib [14], perhaps due to the sequential use of erlotinib in those that had already failed at least 1 conventional chemotherapeutic regimen.

Results from the Spanish Lung Cancer Group showed the feasibility of prospectively screening for EGFR mutation prior to EGFR TKI therapy [15]. Moreover, several phase III trials support the importance of EGFR testing prior to the initiation of first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC (Table 1). Two phase III trials (IPASS and First-SIGNAL) evaluated first-line gefitinib versus chemotherapy in Asian patients selected based on clinical factors known to be associated with higher prevalence of EGFR mutation (adenocarcinoma histology, never or former light smokers) [16,17]. The IPASS mutation subanalysis provided evidence that patients with EGFR mutations respond significantly better to gefitinib than standard platinum-based chemotherapy and those without EGFR mutations respond significantly better to standard chemotherapy [16], highlighting the importance of molecular selection rather than clinical selection for guiding first-line treatment for NSCLC. Two additional phase III Asian trials (WJTOG3405 and NEJ002) utilized molecular section and included only patients with EGFR-mutation positive tumors, with results confirming those from IPASS and First-SIGNAL [18,19,20]. The OPTIMAL phase III trial conducted in China was the first to compare erlotinib with chemotherapy in patients with EGFR-mutation positive tumors [21,22]. Similar to results observed in the gefitinib trials, first-line erlotinib significantly prolonged PFS versus platinum-based chemotherapy. Interim results from the European phase III EURTAC study also show significantly longer PFS with first-line erlotinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with EGFR-mutation positive NSCLC [23], providing further support for molecular testing prior to initiating therapy for advanced NSCLC. Results of clinical trials evaluating investigational irreversible EGFR TKIs may also provide further support for molecular testing in NSCLC. An open-label phase II trial is evaluating PF00299804 in the first-line setting, in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the lung harboring an EGFR mutation [24]. Preliminary results indicated that overall best responses were 1 complete response, 29 partial responses, 28 with stable disease, and 6 with progressive disease. In addition, an open-label, randomized phase III trial (LUX-Lung 3; NCT00949650) is evaluating afatinib versus pemetrexed/cisplatin in the first-line setting, in patients with stage IIIB/IV adenocarcinoma of the lung harboring an EGFR-activating mutation.

Table 1. Phase III Studies Comparing Reversible EGFR TKIs Versus Platinum-based Chemotherapy As First-line Treatment of Advanced NSCLC.

| Study | Patient population | Treatment | HR for progression (95% CI) | RR, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPASS (N = 1,217) [16] | Asian, never or former light smokers, adenocarcinoma | Gefitinib vs carboplatin/gemcitabine | Overall: 0.74 (0.65-0.85)a EGFR-mut pos: 0.48 (0.36-0.64)a EGFR-mut neg: 2.85 (2.05-3.98)a |

Overall: 43.0 vs 32.2e EGFR-mut pos: 71.2 vs 47.3e EGFR-mut neg: 1.1 vs 23.5b |

| First-SIGNAL (N = 309) [17] | Asian, never or former light smokers, adenocarcinoma | Gefitinib vs cisplatin/gemcitabine | Overall: 0.737 (0.580-0.938)b Gefitinib (EGFR-mut neg vs EGFR-mut pos): 0.385 (0.208-0.711)b CT (EGFR-mut neg vs EGFR-mut pos): 1.223 (0.650-2.305)c |

Overall: 53.5 vs 42.0c |

| WJTOG3405 (N = 172) [18] | EGFR-mut pos | Gefitinib vs cisplatin/docetaxel | 0.489 (0.336-0.710)a | 62.1 vs 32.2a |

| NEJ002 (N = 228) [19] | EGFR-mut pos | Gefitinib vs carboplatin/paclitaxel | 0.30 (0.22-0.41)d | 73.7 vs 30.7d |

| OPTIMAL (N = 154) [21] | EGFR-mut pos | Erlotinib vs carboplatin/gemcitabine | 0.164 (NR)a | 83 vs 36a |

| EURTAC (N = 174) [23] | EGFR-mut pos | Erlotinib vs platinum-based chemotherapy | 0.42 (NR)a | 54.5 vs 10.5a |

CI: confidence interval; CT: chemotherapy; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; EGFR-mut pos: EGFR-mutation positive; EGFR-mut neg: EGFR-mutation negative; HR: hazard ratio; NR: not reported; TKIs: tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

P < 0.0001.

P < 0.01.

P > 0.05.

P < 0.001.

P = 0.0001.

EGFR Gene Copy Number, EGFR Protein Overexpression, and Response to EGFR TKIs

EGFR gene amplification and EGFR protein overexpression have also been implicated in predicting response to EGFR TKIs. In the double-blind phase III ISEL study, high EGFR gene copy number was associated with a lower risk of death with gefitinib versus placebo (hazard ratio [HR] for death, 0.61; P = 0.067), and patients with tumors expressing EGFR had significantly improved OS with gefitinib versus those whose tumors did not express EGFR (P = 0.049) [12]. Similarly, univariate analysis from the phase III BR.21 study showed that OS was longer with erlotinib versus placebo in patients whose tumors expressed EGFR (HR, 0.68; P = 0.02) or had high EGFR copy number (HR, 0.44; P = 0.008) [14]. However, multivariate analysis revealed that EGFR expression or EGFR copy number was not significantly associated with survival benefit in either treatment group.

The issue of whether EGFR mutations or increased EGFR copy number (detected via fluorescent in situ hybridization [FISH]) is the better biomarker for EGFR-TKI response was clarified by exploratory analysis of the IPASS trial [25]. Patients with high EGFR copy number had improved PFS with gefitinib versus chemotherapy (HR = 0.66, 95% confidence interval, 0.50-0.88; P = 0.005). However, post hoc exploratory analyses showed this effect was primarily driven by overlap of high EGFR copy number with positive EGFR-mutation status (among the 249 patients who were FISH positive, 190 (78%) also harbored an EGFR mutation). Patients who were FISH positive/mutation negative derived little or no benefit from gefitinib; however, patients with EGFR mutations overall had significantly longer PFS with gefitinib (P <0.001) [16], suggesting that EGFR-mutation status is the primary determinant of response to gefitinib and consequently the preferred biomarker to predict EGFR-TKI benefit.

Secondary EGFR Mutations

While patients with EGFR mutations typically respond to erlotinib or gefitinib, additional mutations in the EGFR gene have been associated with primary and acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy. For example, the T790M point mutation in EGFR exon 20 is present in approximately 50% of patients who initially respond to reversible EGFR TKIs and then develop resistance [26,27,28]. It is noteworthy that the T790M mutation can also occur de novo in EGFR TKI treatment-naive patients [29,30,31,32], suggesting its potential utility as a predictive biomarker.

KRAS Mutations and NSCLC

Increasing evidence indicates that signaling pathways downstream of EGFR (Figure 1) are also involved in the progression of NSCLC and other malignancies [33]. While activating KRAS mutations are uncommon in NSCLCs with squamous histology, they have been identified in 15% to 30% of those with adenocarcinoma histology [34,35,36]. There are no convincing data, however, that KRAS mutations confer resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Instead, because EGFR and KRAS mutations are mutually exclusive in the vast majority of patients, it seems that KRAS positivity may predict resistance to EGFR TKIs (since practically all of these patients are EGFR mutation negative). Furthermore, there are no data to demonstrate that those patients who are KRAS positive are any more resistant to EGFR TKIs than patients who are EGFR negative or KRAS negative. The reason then, to test for KRAS mutation status, is twofold: 1) those who are KRAS positive do not require testing for EML4/ALK translocation and 2) these patients can be entered into clinical trials designed for KRAS-positive patients.

Implications for Pulmonologists

While additional studies are necessary to further define the role of these candidate predictive biomarkers in NSCLC, accumulating evidence suggests that EGFR and KRAS mutations have therapeutic implications and thus, mutational analysis is finding wider application in the clinic. Routine molecular testing of tumor tissue for use in treatment determination represents a significant paradigm shift in NSCLC therapy and therefore calls for a more streamlined and standardized approach to specimen acquisition and processing. It is essential that pulmonologists obtain samples of both sufficient quality and quantity so that adequate specimen is available for both diagnosis and molecular analyses. Some of the invasive and non-invasive approaches that can be adopted to obtain adequate amounts of tissue and appropriate ways to process them are described below.

Tissue Sampling Techniques and Considerations

Tissue for tumor typing and molecular studies can be obtained by a number of techniques ranging from noninvasive to surgical. Because the majority of patients with NSCLC have advanced disease and are not eligible for surgery, nonsurgical procedures are usually a better choice. Several factors must be considered when determining appropriate diagnostic tests, including sensitivity and specificity, false-negative and false-positive rates, procedure morbidity, and tumor location and characteristics [37]. It is important to optimize tissue recovery while decreasing procedure-related morbidity [38].

Sputum cytology is a noninvasive procedure particularly valuable in patients with centrally located tumors [38]; however, tumor location and size affect sensitivity of this method, and rigorous specimen sampling is required to ensure diagnostic accuracy. Flexible bronchoscopy is minimally invasive and most effective with central lesions, but may also be used in conjunction with guided imaging to evaluate peripheral lesions [38]. Bronchoscopy may be performed with or without needle aspiration, which typically obtains cytologic specimens. When larger-gauge needles are used, core samples and material for cell block may also be obtained. Another minimally invasive sampling method, transthoracic needle aspiration, may be used for peripheral, parenchymal lesions; however, there is a high false-negative rate and a risk of pneumothorax associated with this procedure [38,39,40,41]. Some of these techniques may be supplemented with medical imaging, such as endobronchial ultrasound, to guide sampling, avoid surgery, and improve yield and accuracy [37,38]. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a minimally invasive procedure that produces high diagnostic yield allowing for combined pathologic and molecular analysis of metastatic lymph nodes [42]. The ideal methodology of EBUS-TBNA sample handling has recently been published, suggesting rapid on-site cytologic examination to confirm adequate samples for both molecular testing and pathologic diagnosis [42]. If rapid on-site cytology is not available, 3 aspirations per lymph node station or 2 aspirations with 1 tissue core are recommended [43]. While EBUS-TBNA appears particularly promising, regardless of the approach used, it is essential for pulmonologists to confirm that sufficient sample is available to perform appropriate molecular analyses to guide treatment decisions.

Molecular Assays

While larger tissue samples are preferable, diagnostic approaches in NSCLC have shifted toward minimally invasive procedures [44]. Therefore, techniques have been developed whereby molecular testing can be performed on smaller amounts of tissue and specific criteria for sample type, size, collection, and storage have been published (Table 2) [44].

Table 2. Specimen Sampling in the Preanalytical Phase.

| Parameter | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Sample type |

|

| Minimum sample size |

|

| Sample collection and storage |

|

| Tumor heterogeneity |

|

FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization; IHC: immunohistochemistry.

It is important to select a well-validated and robust method for assessing mutation status to minimize false positive (which would indicate EGFR-TKI therapy for a patient more likely to benefit from chemotherapy) or false negative (which would deny a mutation-positive patient from receiving optimal treatment) results. Direct sequencing of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified regions is the most common method of identifying EGFR and KRAS mutations [45], but because of issues with sensitivity and time involved, other techniques have been developed [45]. Sensitive and specific mutational testing kits for EGFR and KRAS are currently commercially available for research use (DxS TheraScreen® EGFR29, ResponseDX™: Lung), and mutational analysis has also been performed in clinical trials.

EGFR gene copy number can be assessed by a variety of methods, including FISH, chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH), and real-time quantitative PCR [45]; however, EGFR amplification has fallen out of favor as a potential predictive marker in NSCLC. Measurement of EGFR expression by IHC is also not commonly used for diagnosis, but a recent analysis from the FLEX trial suggests value as a predictive marker with first-line cetuximab, an EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody, in combination with chemotherapy in NSCLC [46].

While the histologic classification of lung cancer is generally not difficult to determine on surgical specimens, small biopsy samples or cytologic specimens may be inadequate for certain assays [47]. Guidelines for tumor tissue analysis by FISH, IHC, and other methods have been standardized and published (Table 2) [44]. Alternative methods of tissue acquisition are also under investigation. A recent publication reported 92% sensitivity (in 11 of 12 patients) for detection of EGFR mutations in circulating tumor cells isolated from patients with metastatic NSCLC [32].

Future Directions in Individualized Care for Patients with NSCLC

Further efforts toward individualizing therapy for NSCLC have led to the investigation of other candidate biomarkers, including echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion [48,49], although most of these are specific to nonsquamous histology. Isoforms of the EML4-ALK transforming gene and its product have been identified in approximately 5% of patients with NSCLC, who are predominantly younger and light or nonsmokers [50,51,52,53]. Patients with EML4/ALK-expressing NSCLC are generally resistant to EGFR-TKI therapy and have tumors with wild-type EGFR and KRAS [52,54]. Several novel selective ALK inhibitors are in various stages of development [53]. Most recently, crizotinib (Xalkori®), an oral ATP-competitive selective inhibitor of the ALK and cMet (also known as hepatocyte growth factor receptor) tyrosine kinases [55], was approved for the treatment of patients with ALK-positive (by an approved molecular test) locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC based on results from an expansion cohort of a phase I study [56,57] and a phase II study [58].

As our knowledge of molecular markers and their prognostic and therapeutic value in NSCLC has evolved, it is clear that incorporation of testing for more common biomarkers into the initial workup of patients with NSCLC is necessary. Horn and Pao have previously proposed sequential KRAS, EGFR, and EML4-ALK molecular testing based on the gene prevalence and implications of each in NSCLC (Figure 3) [53]. Currently, there are no data to support the initial testing of only KRAS or EGFR mutations, and we instead suggest the simultaneous testing of both EGFR and KRAS. If EGFR mutation testing is positive, this has first-line implications, and if KRAS is positive, it is unlikely that EGFR will also be positive as the 2 mutations are generally mutually exclusive. If KRAS is found to be positive, patients can then be considered for enrollment in clinical trials. Figure 3 shows a proposed molecular testing algorithm.

Figure 3. Suggested algorithm for the molecular testing of patients with NSCLC of adenocarcinoma histology.

Suggested order of testing for KRAS and EGFR mutations and EML4-ALK translocations and potential treatments based on mutation status.

The Biomarker-integrated Approaches of Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer Elimination (BATTLE) program is the first prospective biopsy-mandated study to assess candidate predictive biomarkers as a means of guiding treatment choice in heavily pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC [59]. Fresh core needle biopsy was performed upfront to test for 11 biomarkers, including EGFR and KRAS mutation by PCR, and results from these analyses were used to select treatment based on individual patient profile. Patients with EGFR mutation had an improved 8-week disease control rate when treated with erlotinib (5/7; 71%), while patients with KRAS mutation did not respond well to erlotinib (2/9; 22%). The BATTLE program represents the first trial to evaluate the efficacy of personalized therapy for NSCLC and final results are awaited.

As personalized medicine for NSCLC evolves, pulmonologists and oncologists need to effectively integrate cytologic, molecular, and histologic tests to determine the most appropriate therapy for each individual patient. In addition to the assays discussed, there is ongoing interest in developing and implementing new, less invasive techniques to determine prognosis and identify appropriate therapy for patients with NSCLC. Potential future approaches include utilizing advances in imaging technology as well as serum testing for cell-free tumor nucleic acids.

In conclusion, results from several randomized phase III trials emphasize the importance of molecular testing prior to initiating first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC. Increasing evidence demonstrates that patients with EGFR mutations experience significant benefit with gefitinib or erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy, with an opposite effect occurring in patients with EGFR-mutation negative tumors. As molecular testing becomes standard clinical practice, pulmonologists will play a vital role in ensuring samples of adequate quality and quantity are available for these purposes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for medical and editorial assistance was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Lisa Shannon, PharmD of MedErgy, which was contracted by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals for these services. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and were involved at all stages of manuscript development.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures, 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™. [Accessed May 21, 11 A.D.];Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2011 3 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nscl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunn PA, Jr, Franklin W. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression, signal pathway, and inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:38–44. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.35646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazdar AF. Personalized medicine and inhibition of EGFR signaling in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1018–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0905763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silvestri GA, Rivera MP. Targeted therapy for the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a review of the epidermal growth factor receptor antagonists. Chest. 2005;128:3975–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–81. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarceva® (erlotinib tablets) [package insert] South San Franscisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iressa® (gefitinib tablets) [package insert] Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horiike A, Kimura H, Nishio K, Ohyanagi F, Satoh Y, Okumura S, Ishikawa Y, Nakagawa K, Horai T, Nishio M. Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in transbronchial needle aspirates of non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2007;131:1628–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pao W, Miller VA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations, small-molecule kinase inhibitors, and non-small-cell lung cancer: current knowledge and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2556–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giaccone G, Rodriguez JA. EGFR inhibitors: what have we learned from the treatment of lung cancer? Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:554–61. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, Franklin WA, Dziadziuszko R, Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, Pereira JR, Ciuleanu T, von PJ, Watkins C, Flannery A, Ellison G, Donald E, Knight L, Parums D, Botwood N, Holloway B. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5034–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, van Kooten M, Dediu M, Findlay B, Tu D, Johnston D, Bezjak A, Clark G, Santabarbara P, Seymour L. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, Zhu CQ, Kamel-Reid S, Squire J, Lorimer I, Zhang T, Liu N, Daneshmand M, Marrano P, da Cunha SG, Lagarde A, Richardson F, Seymour L, Whitehead M, Ding K, Pater J, Shepherd FA. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, Porta R, Cardenal F, Camps C, Majem M, Lopez-Vivanco G, Isla D, Provencio M, Insa A, Massuti B, Gonzalez-Larriba JL, Paz-Ares L, Bover I, Garcia-Campelo R, Moreno MA, Catot S, Rolfo C, Reguart N, Palmero R, Sanchez JM, Bastus R, Mayo C, Bertran-Alamillo J, Molina MA, Sanchez JJ, Taron M. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:958–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, Nishiwaki Y, Ohe Y, Yang JJ, Chewaskulyong B, Jiang H, Duffield EL, Watkins CL, Armour AA, Fukuoka M. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JS, Park K, Kim SW, Lee DH, Kim HT, Ham JY, Yun T, Ahn MJ, Ahn JS, Suh C, Lee JS, Han JH, Yu SY, Lee JW, Jo SJ. A randomized phase III study of gefitinib (IRESSA™) versus standard chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus cisplatin) as a first-line treatment for never-smokers with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(9 suppl 1):S283–S284. Abstract PRS.4. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J, Seto T, Satouchi M, Tada H, Hirashima T, Asami K, Katakami N, Takada M, Yoshioka H, Shibata K, Kudoh S, Shimizu E, Saito H, Toyooka S, Nakagawa K, Fukuoka M. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, Gemma A, Harada M, Yoshizawa H, Kinoshita I, Fujita Y, Okinaga S, Hirano H, Yoshimori K, Harada T, Ogura T, Ando M, Miyazawa H, Tanaka T, Saijo Y, Hagiwara K, Morita S, Nukiwa T. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Maemondo M, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, Gemma A, Saijo Y, Yoshizawa H, Morita S, Hagiwara K, Nukiwa T. Final overall survival results of NEJ002, a phase III trial comparing gefitinib to carboplatin (CBDCA) plus paclitaxel (TXL) as the first-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl) Abstract 7519. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu X, Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S on behalf of the OPTIMAL investigators. Efficacy results from the randomised phase III OPTIMAL (CTONG 0802) study comparing first-line erlotinib versus carboplatin (CBDCA) plus gemcitabine (GEM), in Chinese advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (pts) with EGFR activating mutations. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii6. Abstract LBA13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng JF, Liu X, Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S, Lu S, Zhang L on behalf of the OPTIMAL investigators. Updated efficacy and quality-of-life (QoL) analyses in OPTIMAL, a phase III, randomized, open-label study of first-line erlotinib versus gemcitabine/carboplatin in patients with EGFR-activating mutation-positive (EGFR Act Mut+) advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl) Abstract 7520. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosell R, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, Cardenal F, Garcia Gomez R, Pallares C, Sanchez JM, Porta R, Cobo M, Di Seri M, Garrido Lopez P, Insa A, de Marinis F, Corre R, Carreras M, Carcereny E, Taron M, Paz-Ares LG. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy (CT) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (p) with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations: interim results of the European Erlotinib Versus Chemotherapy (EURTAC) phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl) Abstract 7503. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mok T, Spigel DR, Park K, Socinski MA, Tung SY, Kim DW, et al. Efficacy and safety of PF299804 as first-line treatment (TX) of patients (pts) with advanced (adv) NSCLC selected for activating mutation (mu) of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):viii8. Abstract LBA18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Sunpaweravong P, Leong SS, Sriuranpong V, Chao TY, Nakagawa K, Chu DT, Saijo N, Duffield EL, Rukazenkov Y, Speake G, Jiang H, Armour AA, To KF, Yang JC, Mok TS. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2866–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, Johnson BE, Eck MJ, Tenen DG, Halmos B. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, Riely GJ, Somwar R, Zakowski MF, Kris MG, Varmus H. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Yoshida K, Hida T, Tsuboi M, Tada H, Kuwano H, Mitsudomi T. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and acquired resistance to gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5764–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Kuwano H, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8919–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell DW, Gore I, Okimoto RA, Godin-Heymann N, Sordella R, Mulloy R, Sharma SV, Brannigan BW, Mohapatra G, Settleman J, Haber DA. Inherited susceptibility to lung cancer may be associated with the T790M drug resistance mutation in EGFR. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1315–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inukai M, Toyooka S, Ito S, Asano H, Ichihara S, Soh J, Suehisa H, Ouchida M, Aoe K, Aoe M, Kiura K, Shimizu N, Date H. Presence of epidermal growth factor receptor gene T790M mutation as a minor clone in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7854–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maheswaran S, Sequist LV, Nagrath S, Ulkus L, Brannigan B, Collura CV, Inserra E, Diederichs S, Iafrate AJ, Bell DW, Digumarthy S, Muzikansky A, Irimia D, Settleman J, Tompkins RG, Lynch TJ, Toner M, Haber DA. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:366–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di NF, Balfour J, Bardelli A. Biomarkers predicting clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1308–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, Miller VA, Pan Q, Ladanyi M, Zakowski MF, Heelan RT, Kris MG, Varmus HE. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riely GJ, Kris MG, Rosenbaum D, Marks J, Li A, Chitale DA, Nafa K, Riedel ER, Hsu M, Pao W, Miller VA, Ladanyi M. Frequency and distinctive spectrum of KRAS mutations in never smokers with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5731–4. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riely GJ, Marks J, Pao W. KRAS mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:201–5. doi: 10.1513/pats.200809-107LC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez M, Silvestri GA. Endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:180–6. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-081LC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rivera MP, Mehta AC. Initial diagnosis of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132:131S–48S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Boiselle PM, Shepard JO, Trotman-Dickenson B, McLoud TC. Diagnostic accuracy and safety of CT-guided percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy of the lung: comparison of small and large pulmonary nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:105–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.1.8659351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.vanSonnenberg E, Casola G, Ho M, Neff CC, Varney RR, Wittich GR, Christensen R, Friedman PJ. Difficult thoracic lesions: CT-guided biopsy experience in 150 cases. Radiology. 1988;167:457–61. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.2.3357956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kazerooni EA, Lim FT, Mikhail A, Martinez FJ. Risk of pneumothorax in CT-guided transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy of the lung. Radiology. 1996;198:371–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.2.8596834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakajima T, Yasufuku K. How I do it--optimal methodology for multidirectional analysis of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration samples. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:203–6. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318200f496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee HS, Lee GK, Lee HS, Kim MS, Lee JM, Kim HY, Nam BH, Zo JI, Hwangbo B. Real-time endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer: how many aspirations per target lymph node station? Chest. 2008;134:368–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eberhard DA, Giaccone G, Johnson BE. Biomarkers of response to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Working Group: standardization for use in the clinical trial setting. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:983–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.John T, Liu G, Tsao MS. Overview of molecular testing in non-small-cell lung cancer: mutational analysis, gene copy number, protein expression and other biomarkers of EGFR for the prediction of response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;28(1):S14–S23. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirker R, Paz Ares L, Eberhardt WEE, Krzakowski M, Störkel S, Heeger S, von Heydebreck A, Stroh C, O'Byrne KJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression as a predictor of survival for first-line chemotherapy plus cetuximab in FLEX study patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(6 suppl 2):S276. Abstract O01.06. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rossi G, Pelosi G, Graziano P, Barbareschi M, Papotti M. A reevaluation of the clinical significance of histological subtyping of non--small-cell lung carcinoma: diagnostic algorithms in the era of personalized treatments. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:206–18. doi: 10.1177/1066896909336178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, Fujiwara S, Watanabe H, Kurashina K, Hatanaka H, Bando M, Ohno S, Ishikawa Y, Aburatani H, Niki T, Sohara Y, Sugiyama Y, Mano H. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, Nardone J, Lee K, Reeves C, Li Y, Hu Y, Tan Z, Stokes M, Sullivan L, Mitchell J, Wetzel R, Macneill J, Ren JM, Yuan J, Bakalarski CE, Villen J, Kornhauser JM, Smith B, Li D, Zhou X, Gygi SP, Gu TL, Polakiewicz RD, Rush J, Comb MJ. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi YL, Takeuchi K, Soda M, Inamura K, Togashi Y, Hatano S, Enomoto M, Hamada T, Haruta H, Watanabe H, Kurashina K, Hatanaka H, Ueno T, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Sugiyama Y, Ishikawa Y, Mano H. Identification of novel isoforms of the EML4-ALK transforming gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4971–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mano H. Non-solid oncogenes in solid tumors: EML4-ALK fusion genes in lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2349–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong DW, Leung EL, So KK, Tam IY, Sihoe AD, Cheng LC, Ho KK, Au JS, Chung LP, Pik WM. The EML4-ALK fusion gene is involved in various histologic types of lung cancers from nonsmokers with wild-type EGFR and KRAS. Cancer. 2009;115:1723–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horn L, Pao W. EML4-ALK: honing in on a new target in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4232–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, Digumarthy SR, Costa DB, Heist RS, Solomon B, Stubbs H, Admane S, McDermott U, Settleman J, Kobayashi S, Mark EJ, Rodig SJ, Chirieac LR, Kwak EL, Lynch TJ, Iafrate AJ. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4247–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christensen JG, Schreck R, Burrows J, Kuruganti P, Chan E, Le P, Chen J, Wang X, Ruslim L, Blake R, Lipson KE, Ramphal J, Do S, Cui JJ, Cherrington JM, Mendel DB. A selective small molecule inhibitor of c-Met kinase inhibits c-Met-dependent phenotypes in vitro and exhibits cytoreductive antitumor activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7345–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Camidge DR, Bang Y, Kwak EL, Shaw AT, Iafrate AJ, Maki RG, Solomon BJ, Ou SI, Salgia R, Wilner KD, Costa DB, Shapiro G, LoRusso P, Stephenson P, Tang Y, Ruffner K, Clark JW. Progression-free survival (PFS) from a phase I study of crizotinib (PF-02341066) in patients with ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, Ou SH, Dezube BJ, Janne PA, Costa DB, Varella-Garcia M, Kim WH, Lynch TJ, Fidias P, Stubbs H, Engelman JA, Sequist LV, Tan W, Gandhi L, Mino-Kenudson M, Wei GC, Shreeve SM, Ratain MJ, Settleman J, Christensen JG, Haber DA, Wilner K, Salgia R, Shapiro GI, Clark JW, Iafrate AJ. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crino L, Kim D, Riely GJ, Janne PA, Blackhall FH, Camidge DR, Hirsch V, Mok T, Solomon BJ, Park K, Gadgeel SM, Martins R, Han J, De Pas TM, Bottomley A, Polli A, Peterson J, Tassell VR, Shaw AT. Initial phase II results with crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): PROFILE 1005. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15s) Abstract 7514. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim ES, Herbst RS, Lee JJ, Blumenschein GRJ, Tsao A, Alden CM, Tang X, Liu S, Stewart DJ, Heymach JV, Tran HT, Hicks ME, Erasmus JJ, Gupta S, Powis G, Lippman SM, Wistuba II, Hong WK. The BATTLE trial (Biomarker-integrated Approaches of Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer Elimination): personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Presented at: 101st Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; April 17-21, 2010; Washington, DC. 2010. [Google Scholar]