Abstract

The methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) is a widely expressed protein, the mutations of which cause Rett syndrome. The level of MeCP2 is highest in the brain where it is expressed selectively in mature neurons. Its functions in postmitotic neurons are not known. The MeCP2 gene is alternatively spliced to generate two proteins with different N termini, designated as MeCP2-e1 and MeCP2-e2. The physiological significance of these two isoforms has not been elucidated, and it is generally assumed they are functionally equivalent. We report that in cultured cerebellar granule neurons induced to die by low potassium treatment and in Aβ-treated cortical neurons, Mecp2-e2 expression is upregulated whereas expression of the Mecp2-e1 isoform is downregulated. Knockdown of Mecp2-e2 protects neurons from death, whereas knockdown of the e1 isoform has no effect. Forced expression of MeCP2-e2, but not MeCP2-e1, promotes apoptosis in otherwise healthy neurons. We find that MeCP2-e2 interacts with the forkhead protein FoxG1, mutations of which also cause Rett syndrome. FoxG1 has been shown to promote neuronal survival and its downregulation leads to neuronal death. We find that elevated FoxG1 expression inhibits MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity. MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity is also inhibited by IGF-1, which prevents the neuronal death-associated downregulation of FoxG1 expression, and by Akt, the activation of which is necessary for FoxG1-mediated neuroprotection. Finally, MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity is enhanced if FoxG1 expression is suppressed or in neurons cultured from FoxG1-haplodeficient mice. Our results indicate that Mecp2-e2 promotes neuronal death and that this activity is normally inhibited by FoxG1. Reduced FoxG1expression frees MecP2-e2 to promote neuronal death.

Introduction

The methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) is a widely expressed protein, mutations of which cause Rett syndrome (Chahrour and Zoghbi, 2007; Gonzales and LaSalle, 2010; Calfa et al., 2011). Levels of MeCP2 are highest in the brain. Several lines of evidence suggest involvement in various neurodevelopmental processes (Gonzales and LaSalle, 2010; Calfa et al., 2011). MeCP2 is expressed at much higher levels in the postnatal brain where it is present selectively in mature neurons (Jung et al., 2003; Kishi and Macklis, 2004). Its role in mature neurons and the adult brain is not known. Several lines of evidence suggest that MeCP2 is a global transcriptional repressor that acts by binding to methylated DNA, leading to the alteration of chromatin structure to a transcriptionally repressed state. Surprisingly, however, only a few targets of MeCP2-mediated transcriptional repression have been identified so far. More recent studies suggest that MeCP2 activates gene expression by binding to promoters in a sequence-specific manner in cooperation with other transcription factors (Chahrour et al., 2008). Indeed, a majority of MeCP2-bound promoters are found to be from active genes, indicating that the effects of MeCP2 on gene expression are complex (Yasui et al., 2007; Chahrour et al., 2008).

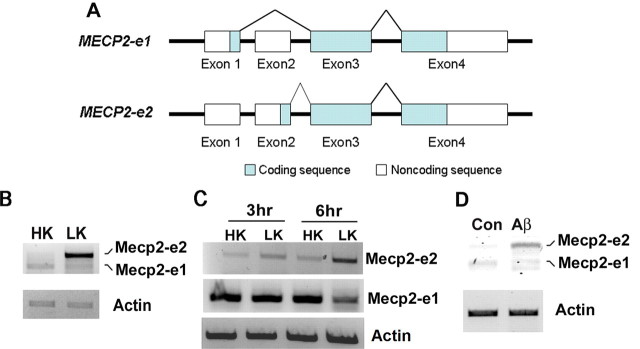

The MeCP2 gene is alternatively spliced to generate two different proteins with distinct translation initiation sites and N termini (Fig. 1A) (Kriaucionis and Bird, 2004; Mnatzakanian et al., 2004). The MeCP2-e1 isoform is encoded by exons 1, 3, and 4, whereas the e2 isoform is encoded by exons 2, 3, and 4. Except for the 21 aa region unique to the e1 isoform and the 9 aa region unique to e2, the two isoforms are identical. Previous analysis has revealed that the Mecp2-e2 isoform is not expressed in non-mammalian vertebrates and is 10 times less abundant than the e1 isoform in the postnatal brain (Dragich et al., 2007). Although Mecp2-e1 and Mecp2-e2 display distinct expression patterns within different brain areas and developmental stages (Dragich et al., 2007), the functional difference between the two isoforms has not been adequately investigated, and the general assumption is that there is none.

Figure 1.

Expression of Mecp2 isoforms in neurons primed to undergo apoptosis. A, Schematic representation of Mecp2–e1 and Mecp2–e2 isoforms. Mecp2–e1 isoform comprises exons 1, 3, and 4. Mecp2–e2 isoform comprises exons 2, 3, and 4. B, RT-PCR analysis of RNA prepared from cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) treated with high potassium (HK) or low potassium (LK) for 4 h was performed with primers recognizing both e1 and e2 isoforms. β-actin served as the loading control. Mecp2–e2 isoform is upregulated in LK conditions. C, RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from 3 and 6 h HK- and LK-treated CGNs using primers specific for e1 or e2 isoform. Mecp2–e2 isoform is upregulated in LK conditions. D, RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from cortical neurons treated with 10 μm Aβ for 6 h. Primers recognizing both Mecp2 e1 and e2 isoforms were used. Mecp2–e2 isoform is upregulated in cortical neurons treated with Aβ.

We report that elevated expression of the MeCP2-e2 isoform, but not the MeCP2-e1 isoform, promotes neuronal death. In healthy neurons this death-promoting activity of Mecp2 is kept in check through interaction with FoxG1, a protein that promotes neuronal survival and mutations of which are also linked to Rett syndrome (Jacob et al., 2009; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2010; Mencarelli et al., 2010; Philippe et al., 2010; Le Guen et al., 2011). Together, our results describe for the first time functional differences between the two Mecp2 isoforms and report a novel interaction between Mecp2 and FoxG1, two proteins linked to Rett syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Primary antibodies used in this article were as follows: Flag (F1804; Sigma-Aldrich), HA (sc-805 and sc-7392; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), tubulin (sc-8035; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GFP (sc-9996 and sc-8334; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Myc (9B11#2276;Cell Signaling Technology), pAktSer473 (4060;Cell Signaling Technology), and MeCP2 (07–013, Millipore; and 3456, Cell Signaling Technology). FoxG1 antibody was generated as described by Dastidar et al. (2011). For Western blotting, the antibodies were used at a dilution between 1:500 and 1:1000, and the secondary antibodies (from Pierce) were used at concentrations of either 1:10,000 or 1:20,000. For immunocytochemistry, primary antibodies were used at a dilution ranging from 1:100 to 1:400, and Texas Red- or FITC-tagged secondary antibodies (purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used at a dilution of 1:85.

Plasmids.

The FoxG1-Flag expression vector was a kind gift from Dr. Stefano Stifani of McGill University (Montreal, QC, Canada). The MeCP2-e1-GFP, MeCP2-e2-GFP, MeCP2-e1-Myc/His, and MeCP2-e2-Myc/His plasmids were constructed by Dr. Vinodh Narayanan of the Neurology Research Department, Barrow Neurological Institute (Phoenix, AZ). The CA-Akt-HA plasmid and the pLKO.1-TRC shRNA control plasmid (Con) were both purchased from Addgene. The pSuper-neo/gfp-Pan. Akt and pSuper-neo/gfp-scrambled-Akt shRNA (Delgado-Esteban et al., 2007) plasmid vectors were a kind gift from Dr. Juan P. Bolanos of the University of Salamanca (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; Salamanca, Spain). The MeCP2-del9-myc was cloned using the following primers: Del9 forward 5′-GCTTGGTACCGAGCTCGGATCC ATGGA GGAAAAGTCAGAAGA-3′ and del9 reverse 5′-TCTTCTGACTTTTCCTCCATGGATCCGA GCTCGGTACCAAGC-3′.

To create the FoxG1 deletion constructs at the DNA binding region the following primers were used: FoxG1-BamH1-Fwd: 5′-CTAGGGATCCATGCTGGACATGGGAGATAG-3′; FoxG1-1–191-Xho1-Flag-rev: 5′-CTAGCTCGAGCTA CTTGTCGTC ATCGTCTTTGTAGTC CTCGGGACTCTGCCTGATGG-3′; FoxG1-1–233-Xho1-Flag-Rev: 5′-CTAGCTCGAGCTACTTGTCGTCATCGT CTTTGTAGTCCTTCACGAAGCACTTGTTGA-3′; and FoxG1-1–254-Xho1-Flag-Rev: 5′-CTAGCTCGAGCTACTTGTCGTCATC GTCTTTGTAGTCGTCGCTCGACGGGTCGAGCA-3′.

FoxG1-haplodeficient mice.

FoxG1+/Cre mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (stock #006084). In these mice, originally generated by Hébert and McConnell (2000), the FoxG1 gene is disrupted by knockin of Cre. FoxG1+/Cre male mice were bred with FoxG1+/+ female mice to obtain wild-type and FoxG1+/Cre pups. Tail-tip DNA was collected from offspring 2 d after birth and genotyping was performed by PCR. The pups were sacrificed between postnatal day 5 and day 7 to make primary cerebellar granule neuronal cultures from them. All experimental protocols were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Dallas. The following primers were used for genotyping, as suggested by The Jackson Laboratory: WT F: 5′-GACGGCAAGTACGAGAAGC-3′; WT R: 5′-TCACGAAGCACTTGTTGAGG-3′; Mutant F: 5′-AGTATTGTTTTGCCAAGTTCTAAT-3′; and Mutant R: 5′-TCCTATAAGTTGAATGGTATTTTG-3′.

Mecp2 transgenic mice.

Hemizygous FVB-Tg(MECP2)3Hzo/J females, initially generated by Huda Zoghbi's laboratory (Collins et al., 2004) and purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, were bred to FVB/NJ males (also from The Jackson Laboratory). Only females hemizygous for the Mecp2 transgene were used for breeding, because hemizygous males are sterile. Pups were genotyped by collection of tail-tip DNA on day 4 after birth for utilization in tissue culture experiments. The following primers were used for genotyping, as suggested by The Jackson Laboratory: Transgene F: 5′-CGCTCCGCCCTATCTCTGA-3′; Transgene R: 5′-ACAGATCGGATAGAAGACTC-3′; Internal Positive Control F: 5′-CAAATGTTGCTTGTCTGGTG-3′; and Internal Positive Control R:5′-GTCAGTCGAGTGCACAGTTT-3′.

3-Nitropropionic acid treatment and experimental design.

Ten-week-old C57BL/6 male mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. 3-Nitropropionic (3-NP) acid treatment and experimental design were performed as described by Chin et al. (2004). Briefly, 3-NP was dissolved in water, and the solution brought to pH 7.4 with sodium hydroxide. Freshly prepared 3-NP was administered in 10 intraperitoneal injections (50–55 mg/kg twice a day for 5 d). Control animals received saline injections. On the day following the first and third days of injection, mice were deeply anesthetized. Brains were removed, and protein or RNA was extracted. For both mRNA and protein, we harvested the striatum and rest of the brain [or as the other brain part (OBP)], and the experiment was performed in triplicate.

Analysis of the R6/2 transgenic mouse model.

Female mice hemizygous for B6CBA-Tg(HDexon1)62Gpb/1J (via ovarian transplant) were bred to B6CBAF1/J males; both obtained from The Jackson Laboratory as previously described by Chen and D'Mello (2010). Tail-tip DNA was collected from offspring 10–14 d after birth, and genotyping was performed by PCR. Wild-type and transgenic littermate (indicated in the study as R6/2) pairs were killed by carbon dioxide inhalation at 13 weeks of age. The brains were dissected, and the striatum was separated from the rest of the brain for analysis.

Primary neuronal culture and transfection.

Cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) from both male and female rat pups were cultured and transfected as described by Dastidar et al. (2011). When performed, treatment with pharmacological inhibitors (all purchased from EMD Biosciences) was done as described previously by Bardai and D'Mello (2011) and Dastidar et al. (2011). The concentrations used were as follows: SP600125 at 10 μm, roscovitine at 50 μm, and SB415286 at 30 μm. IGF-1 was used at 25 ng/ml, and Akt Inhibitor X at 10 μm. Viability of rat CGNs was quantified 24 h after high potassium (HK) or low potassium (LK) treatment. CGNs were also cultured from FoxG1+/+ or FoxG1+/Cre mice. In these mouse cultures, treatment with HK/LK was for 12 h. Cortical neurons were cultured from 17- to 18-d-old rat embryos (both genders) and transfected as previously described by Dastidar et al. (2011). Treatment with Aβ at 10 μm was performed 2 d after plating, as described by Ma and D'Mello (2011) and viability assessed 48 h later. Neuronal viability following transfection was evaluated as described previously by Dastidar et al. (2011). Briefly, the proportion of transfected neurons (identified by immunocytochemistry) displaying condensed or fragmented nuclei (visualized by DAPI staining) was scored as apoptotic.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were done as previously described in Dastidar et al. (2011). Briefly, 80% of the whole-cell lysate (WCL) was used as input for pull-down experiments, and 5–10% of WCL was used to determine expression of respective proteins.

RT-PCR.

RNA was harvested using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 3–5 μg of RNA was used to make cDNA with the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis system from Invitrogen. RT-PCR was performed using standard conditions and the following primers: Mecp2-e1-specific and Mecp2-e2-specific forward primer 5′-GGAGGAGGCGAGGAGGAGA-3′; Mecp2-e1-specific and Mecp2-e2-specific reverse primer 5′-GGCTGAAGGCTGTAGTGGT-3′; Mecp2-e1 forward 5′-GAGGCGAGGAGGAGAGACTG-3′; Mecp2-e1 reverse 5′-TCTTCTGACTTTTCCTCCCTG-3′; Mecp2-e2 forward 5′-TGGTAGCTGGGATGTTAGG-3′; and Mecp2-e2 reverse 5′-GAGATTTGGGCTTCTTAGGT-3′.

shRNA-mediated suppression.

shRNA-mediated suppression in neurons was performed as described earlier by Dastidar et al. (2011). An MeCP2 shRNA construct, TRCN0000039083 (designated as shMeCP2), and an shRNA against FoxG1 (designated as shFoxG1) were used in this study. The pLKO.1-TRC control vector (indicated in the text and Fig. 4 as Con) expresses a nonhairpin 18 bp insert.

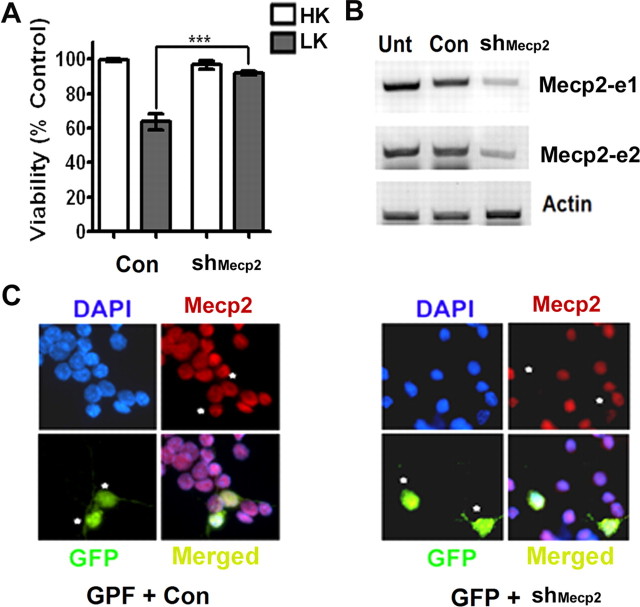

Figure 4.

Effect of suppression of Mecp2–e1 and Mecp2–e2 expression in neurons using shRNA. A, Viability of CGNs transfected with control shRNA (Con) or shMecp2. Viability of transfected neurons was quantified and normalized to the viability of control cultures (Con-transfected cells). Knocking down endogenous levels of Mecp2 increased viability of neurons treated with LK. B, RT-PCR analysis of endogenous Mecp2 expression in HT22 cells that were either untransfected (Unt) or transfected with control shRNA (Con) or shMecp2. shMecp2 was able to knock down endogenous expression of both the isoforms of Mecp2. C, Immunocytochemistry using Mecp2 antibody showing knockdown of endogenous Mecp2 in neurons cotransfected with GFP and shMecp2 (indicated by asterisk). In neurons cotransfected with GFP and Con (indicated by asterisk) the level of endogenous Mecp2 is not reduced.

siRNA-mediated suppression.

For isoform-specific knockdown 5′-6FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein)-tagged MISSION siRNAs (from Sigma-Aldrich) were used. 5′-6FAM-tagged MISSION siRNA Universal Negative Control 1 (SIC001) indicated as Control siRNA, e1.1 siRNA (sense = CGGAUGGCGUCCCUCCUCUdTdT, antisense = AGAGGAGGG ACGCCAU CCGdTdT), e1.2 siRNA (sense = GGGCGACACGGCUGGCGGAdTdT, antisense = UCCGCCAGCCGUGUCGCCCdTdT), e2.1 (sense = CAUGGUAGCUGGGAUGUUAdTdT, antisense = UAACAUCCCAGCUACCAUGdTdT), and e2.2 (sense = CCAUGGUAGCUGGGAUGUUdTdT, and antisense = AACAUCCCAGCUACCAUGGdTdT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The effectiveness of siRNAs to suppress Mecp2 expression was tested in HT22 cells. Briefly, HT22 cells were transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) using manufacturer's instruction. Seventy-six hours after transfection of the HT22 cells, mRNA was harvested using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol; cDNA was prepared from the mRNA and analyzed using PCR as described above. CGNs were transiently transfected on day 4 using 2 μg of marker plasmid (pEGFP) together with 200 nm siRNA (Björkblom et al., 2008). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated with either HK or LK for 24 h and then subjected to immunocytochemistry using GFP antibody. Viability of transfected neurons was determined as described earlier by Dastidar et al. (2011).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done using unpaired two-tailed t test (Student's t test), and the results are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Asterisks indicate the following p values: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. All viability experiments were done in duplicate and repeated at least three times. For each experiment, ≥150 transfected cells were counted.

Results

Expression of Mecp2-e2 is upregulated during neuronal death in vitro and in vivo

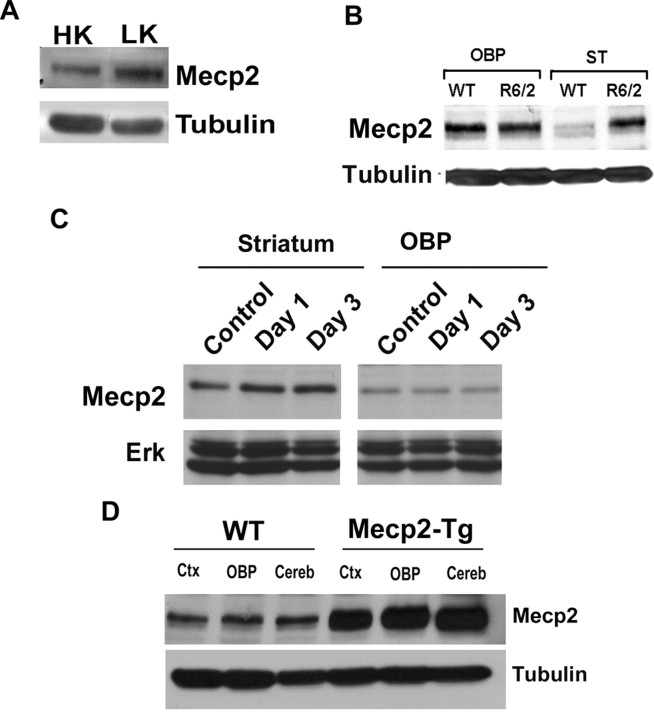

When CGNs cultured from postnatal rats or mice are switched from a medium containing depolarizing levels of potassium (HK) to nondepolarizing levels of potassium (LK), they undergo apoptosis (D'Mello et al., 1993). As shown in Figure 1, B and C, the expression of Mecp2-e2 at the mRNA level is elevated in CGNs primed to die by LK treatment. In contrast, the expression of Mecp2-e1 is slightly reduced (Fig. 1B,C). A similar upregulation of Mecp2-e2 is observed in embryonic cortical neurons induced to die by exposure to Aβ peptide, a cell culture model of Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 1D). Upregulation of Mecp2 expression in LK-treated CGNs was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). Like all other commercially available antibodies and antibodies described in the literature, the antibody used in the analysis could not distinguish between the two isoforms. Based on the RT-PCR results, however, it is likely that the upregulation of Mecp2 immunoreactivity in neurons primed to die is due to the stimulation of e2 expression. To examine whether Mecp2 expression was also deregulated in in vivo models of neurodegenerative disease, we analyzed expression in the R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease (HD) (Mangiarini et al., 1996; Ferrante et al., 2003; Hockly et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005). R6/2 mice develop selective striatal neuropathology and behavioral deficits starting at ∼10 weeks. As shown in Figure 2B, Mecp2 immunoreactivity is markedly induced in the striatum of 13 week R6/2 mice, but not in lysates prepared from other brain parts. Selective upregulation of expression of Mecp2 in the striatum was also observed at 11 weeks (data not shown). We also analyzed Mecp2 expression in the striatum after administration of 3-NP, a commonly used chemical model of HD that faithfully recapitulates the neurodegenerative and behavioral abnormalities observed in patients (Beal et al., 1993; Escartin et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010). As observed in the R6/2 genetic model, upregulation of Mecp2 was observed in the striatum but not in OBP of mice administered with 3-NP (Fig. 2C). Using the 3-NP administration conditions, we have previously reported that striatal degeneration is extensive by 3 d (Chin et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010). Validation of the MeCP2 antibody was achieved by Western blot analysis using lysates prepared from the brains of Mecp2 transgenic mice (Collins et al., 2004) and nontransgenic littermates (Fig. 2D). Further demonstration of antibody specificity was achieved by Western blot analysis of lysates prepared from HEK293T cells transfected with plasmids encoding MeCP2-e1-GFP, MeCP2-e2-GFP (Fig. 3D).

Figure 2.

Expression of Mecp2 isoforms in neurons primed to undergo apoptosis and in mouse models of neurodegeneration. A, Western blot analysis of Mecp2 protein in high potassium (HK)- or low potassium (LK)-treated cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs). The level of Mecp2 is upregulated in LK. B, Lysates were prepared from the striatum (ST) and all other brain parts (OBP) combined of 13-week-old R6/2 mice and nontransgenic littermates (WT), and subjected to Western blot analysis using an MeCP2 antibody. Tubulin served as the loading control. The level of Mecp2 is upregulated in the ST of R6/2 mice. C, Western blot analysis of ST and OBP of 10-week-old mice injected with either saline (control) or with 3-NP for 1 and 3 d. The blot was probed with an MeCP2 antibody. Total Erk served as the loading control. The level of Mecp2 was upregulated in the ST of 3-NP-injected mice as opposed to the saline-injected mice. D, Protein lysates obtained from the cortex (ctx), cerebellum (cereb), or the remainder of OBP of wild-type and Mecp2-overexpressing transgenic mice were subjected to Western blot analysis with an MeCP2 antibody. The elevated expression of the Mecp2 transgene is clearly detected by the antibody. In the brain part of the transgenic mice, Mecp2 was produced at least 3 times more than its wild-type littermate.

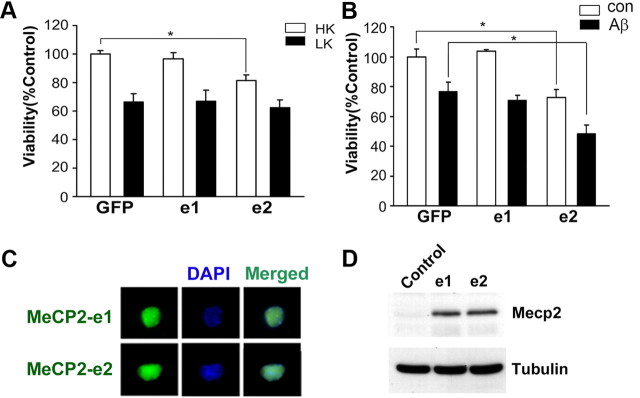

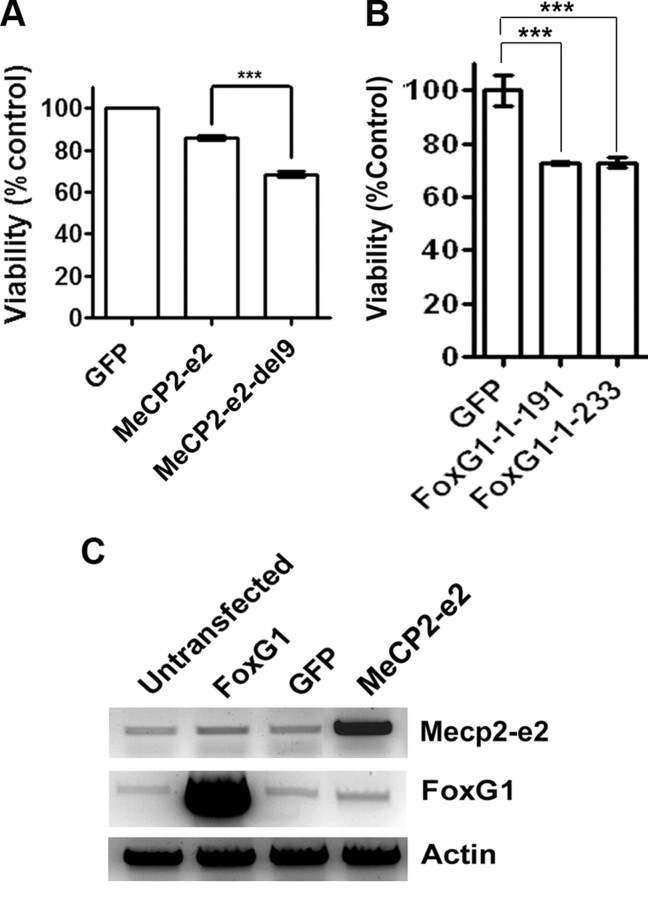

Figure 3.

MeCP2–e2 isoform but not MeCP2–e1 isoform promotes neuronal death. A, Viability of CGNs transfected with GFP, MeCP2–e1-GFP (e1), or MeCP2–e2-GFP (e2) and switched to high potassium (HK) or low potassium (LK) medium for 24 h. The viability was normalized to GFP-transfected cultures treated with HK. MeCP2–e2 killed healthy neurons treated with HK. B, Viability of cortical neurons transfected with GFP, e1, or e2 and treated with no additives (con) or 10 μm Aβ for 48 h. Survival is normalized to GFP-transfected cortical neurons treated with no additives (con). MeCP2–e2 killed neurons treated with no additives (Con) as well as neurons treated with Aβ. C, CGNs transfected with MeCP2–e1 and MeCP2–e2 were subjected to immunocytochemistry using antibody against GFP. MeCP2–e1 and MeCP2–e2 were expressed at similar levels, as evident through immunocytochemistry. DAPI staining was performed to identify the nucleus of the cells. D, Western blot using MeCP2 antibody showing MeCP2–e1-GFP and MeCP2–e2-GFP isoform are expressed similarly in HEK293T cells. Tubulin served as the loading control. Control indicates untransfected HEK293T cells.

Mecp2-e2 promotes neuronal death

The upregulation of Mecp2-e2 expression in neurons primed to die suggested that elevated levels of the Mecp2-e2 isoform contributes to neuronal death. To investigate this possibility, we expressed the two isoforms in neurons. Whereas forced expression of MeCP2-e1 had no effect on viability, the expression of MeCP2-e2 promoted cell death in otherwise healthy CGNs (Fig. 3A). Likewise, the expression of MeCP2-e2 promoted the death of cortical neurons and increased the extent of death induced by Aβ treatment (Fig. 3B). To rule out the possibility that the two isoforms behaved differently due to differential expression levels, we transfected the two isoforms in CGNs. Immunocytochemical analysis of CGNs indicated that both the isoforms were expressed equally and inside the nucleus (Fig. 3C). Similar efficiency of expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis of HEK293T cells transfected with each of the two MeCP2 isoforms (Fig. 3D).

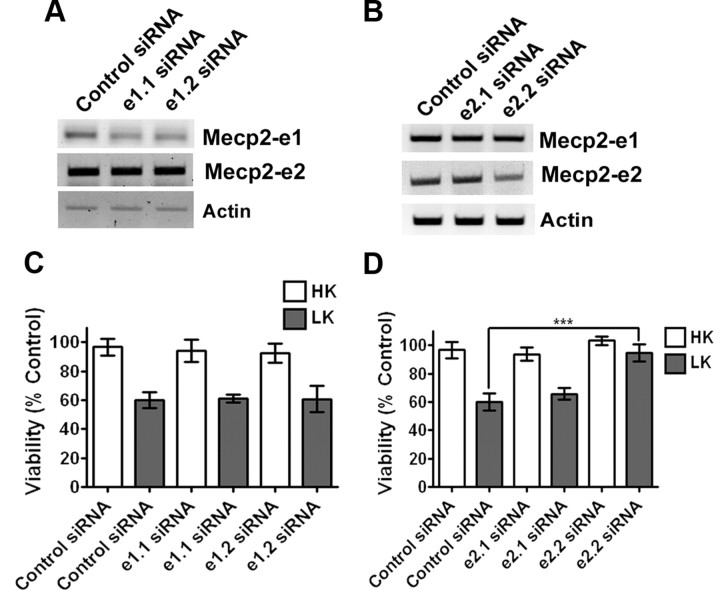

The elevation of Mecp2-e2 expression in neurons primed to die along with the toxicity observed when this isoform is overexpressed in otherwise healthy neurons raised the possibility that knocking down endogenous levels of Mecp2-e2 would protect neurons from death. Suppression of Mecp2 expression with an shRNA construct designed to knock down both isoforms protected CGNs from LK-induced death (Fig. 4A). Control experiments confirmed that the shRNA suppressed expression of the two Mecp2 isoforms efficiently (Fig. 4B,C). To rule out the involvement of Mecp2-e1 in neuronal toxicity, we knocked down expression of each isoform using specific siRNAs. Two siRNAs were synthesized that targeted the unique N-terminus regions of each of the two isoforms. When tested for efficacy, both siRNAs synthesized against the e1 knocked down its expression, but not the expression of the e2 isoform (Fig. 5A). In comparison, only one of the two siRNAs synthesized to target the 9 aa sequence unique to the e2 isoform (siRNA-e2.2) was effective at knocking down its expression (Fig. 5B). While the knockdown of endogenous Mecp2-e1 with the two siRNAs had no significant effect on CGN survival (Fig. 5C), the knockdown of the e2 isoform using siRNA-e2.2 prevented LK-induced neuronal death (Fig. 5D).Together, these results demonstrate that an elevated level of MeCP2-e2 promotes neuronal death.

Figure 5.

Effect of suppression of Mecp2–e1 and Mecp2–e2 expression in neurons using siRNA. A, RT-PCR analysis of endogenous Mecp2 expression in HT22 cells that were transfected with two different siRNAs (e1.1 and e1.2) against Mecp2–e1 isoform as indicated in the figure. The siRNA was able to knock down endogenous Mecp2–e1 isoform. B, RT-PCR analysis of endogenous Mecp2 expression in HT22 cells that were transfected with two differenet siRNAs (e2.1 and e2.1) against Mecp2–e2 isoform. One of the siRNAs, e2.2 siRNA, was able to knock down endogenous Mecp2–e2 isoform. C, Viability of CGNs cotransfected with GFP and siRNA (control or Mecp2–e1 specific). Viability was normalized to CGNs cotransfected with control siRNA and GFP. Knocking down endogenous Mecp2–e1 had no effect on neuronal survivability. D, Viability of CGNs cotransfected with GFP and siRNA (control or Mecp2–e2 specific). Viability was normalized to CGNs cotransfected with control siRNA and GFP. Knocking down endogenous Mecp2–e2 protected neurons against LK-mediated cell death.

Neurotoxic activity of MeCP2-e2 is inhibited by FoxG1 through direct interaction

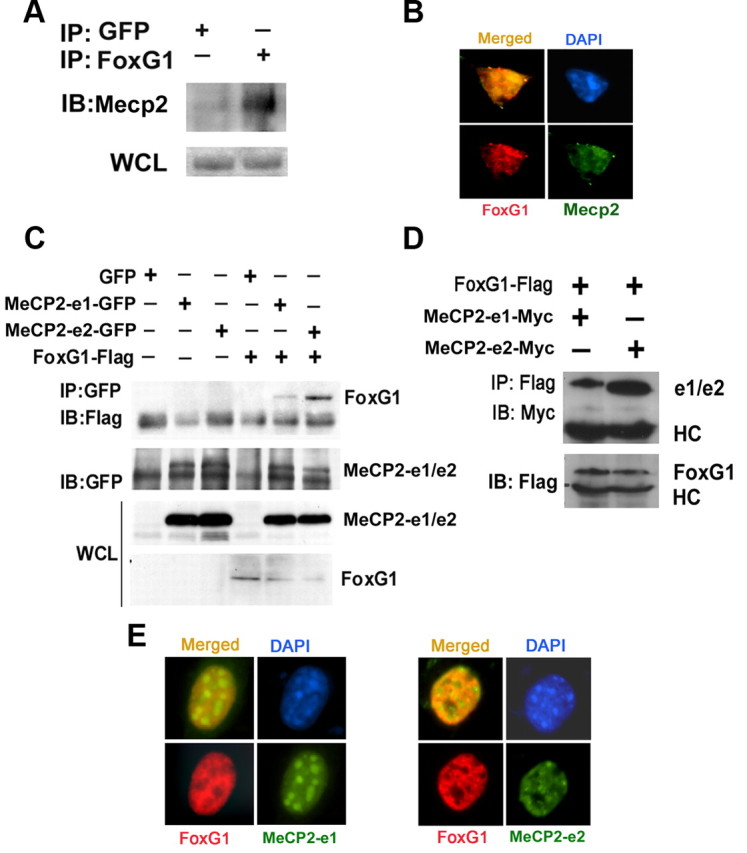

Several recent studies have shown that mutation in the gene encoding FoxG1, a member of the forkhead family of transcription factors, also causes Rett syndrome (Jacob et al., 2009; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2010; Mencarelli et al., 2010; Philippe et al., 2010; Le Guen et al., 2011). Although studied extensively in the context of brain development where it plays a critical role in regulating the proliferation of neural progenitor cells (Tao and Lai, 1992; Xuan et al., 1995; Hanashima et al., 2002, 2004), the physiological significance of FoxG1 in the mature brain is poorly understood. We recently reported that elevated expression of FoxG1 is necessary for the survival of postmitotic neurons (Dastidar et al., 2011). To investigate the relationship between Mecp2 and FoxG1, we examined whether they interacted physically. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that Mecp2 interacts with FoxG1 in CGNs (Fig. 6A). In accordance with this finding, immunocytochemical analysis revealed extensive colocalization between FoxG1 and Mecp2 in CGNs (Fig. 6B). As expected, given the sharp downregulation of FoxG1 expression in LK-treated neurons, the interaction between Mecp2 and FoxG1 is lower in LK (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Analysis of interaction between FoxG1 and Mecp2. A, CGN lysates were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation using FoxG1 antibody. The immunoprecipitate was analyzed by Western blot using MeCP2 antibody. FoxG1 was able to pull down Mecp2; however, GFP was unable to pull down Mecp2. An aliquot of the WCL (whole cell lysate) was also analyzed for Mecp2. B, Immunocytochemical analysis of CGNs using antibodies against FoxG1 and Mecp2. Mecp2 and FoxG1 colocalize. C, Lysates from HEK293T cells transfected with GFP, MeCP2–e1-GFP, MeCP2–e2-GFP, and Flag-FoxG1 plasmids as shown were immunoprecipitated using GFP antibody. Immunoblotting (IB) was performed using Flag antibody (top) and then reprobed with GFP antibody (bottom). Western blotting of WCL using GFP and Flag antibodies is also shown. FoxG1 interacts with both the isoforms of MeCP2 with a greater affinity for MeCP2–e2 isoform IP indicates immunoprecipitation. D, Lysates from HEK293T cells cotransfected with FoxG1-Flag and MeCP2–e1-Myc or MeCP2–e2-Myc were immunoprecipitated using Flag antibody. The immunoprecipitate was subjected to immunoblotting with Myc antibody (top). The blot was reprobed with Flag antibody (bottom). FoxG1 interacted with MeCP2–e2 isoform more strongly than the MeCP2–e1 isoform. E, HT22 cells were cotransfected with FoxG1-Flag and either MeCP2–e1-GFP or MeCP2–e2-GFP followed by immunocytochemistry using Flag and GFP antibodies. MeCP2–e2 and FoxG1 colocalize more than MeCP2–e1 and FoxG1.

Since the Mecp2 antibody does not distinguish between the two isoforms, it was not clear whether FoxG1 interacted with one or both isoforms. To address this, we coexpressed FoxG1 with GFP-tagged forms of either MeCP2-e1 or MeCP2-e2 in HEK293T cells. Although both isoforms interacted with FoxG1, the level of interaction was substantially higher with the e2 form (Fig. 6C). To rule out the possibility that the tag contributed to a differential interaction, we repeated the experiment using myc-tagged forms of the two isoforms. Once again, interaction between FoxG1 and MeCP2-e2 was higher than that observed with MeCP2-e1 (Fig. 6D). Results from immunocytochemical analysis were consistent with a higher level of interaction with MeCP2-e2. As shown in Figure 6E, while extensive colocalization is seen when FoxG1 and MeCP2-e2 are coexpressed, overlap is modest with MeCP2-e1.

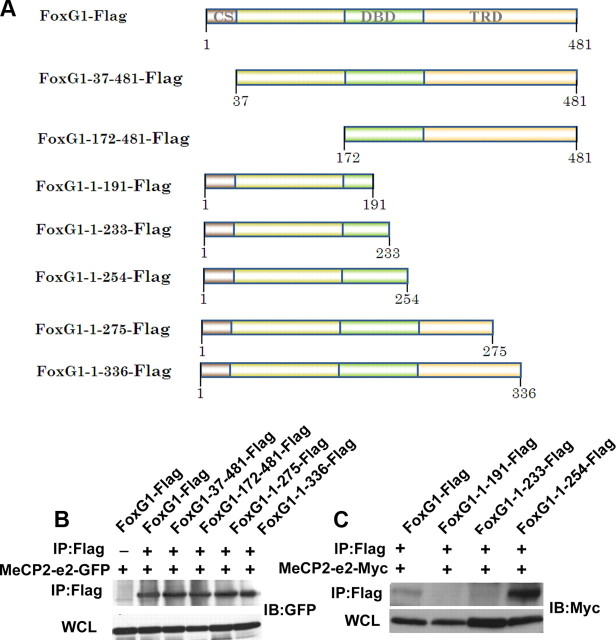

To identify the region within FoxG1 that interacts with MeCP2, we used different N- and C-terminal deletion constructs generated as part of a previous study (Dastidar et al., 2011) (Fig. 7A). As shown in Figure 7B, interaction with MeCP2-e2 was observed with both construct spanning the 172–481 regions and a construct spanning the 1–275 region of FoxG1. This suggests that binding occurs between residues 171 and 275, a region within the DNA-binding region of FoxG1. To map the binding site in more detail, we generated additional FoxG1 deletion constructs (Fig. 7A). While a construct spanning the 1–254 region of FoxG1 displayed interaction with MeCP2-e2, a construct with the 1–233 region did not, mapping the site of interaction to the 20 aa region between 234 and 254 (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Analysis of interaction between FoxG1 and MeCP2–e2. A, Schematic representation of the deletion constructs of FoxG1 used in this study. CS, Conserved sequence; DBD, DNA binding domain; TRD, transcriptional repression domain. B, Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of deletion constructs of FoxG1 (FoxG1-37–481, FoxG1-172–481, FoxG1-1–275, and FoxG1-1–336) and MeCP2–e2-GFP. The immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with Flag antibody and immunoblotting (IB) was performed with GFP antibody. C, Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of deletion constructs of FoxG1 (FoxG1-1–191, FoxG1-1–233,and FoxG1-1–254) and MeCP2–e2-Myc. The immunoprecipitation was performed with Flag antibody and immunoblotting was performed with Myc antibody. FoxG1-1–191 and FoxG1-1–233 do not interact with MeCP2–e2.

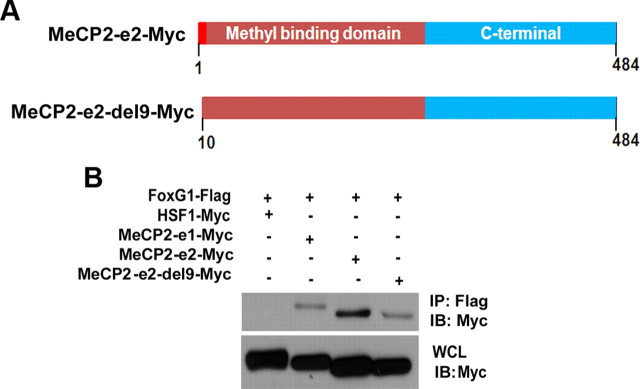

We proceeded to map the region within MeCP2 that bound FoxG1. Since the only sequence in MeCP2-e2 that is missing from the e1 isoform is the 9 aa residues at the N terminus, it was likely that the higher level of interaction between MeCP2-e2 and FoxG1 was due to this motif. Indeed, deletion of the first 9 aa of MeCP2-e2 to obtain MeCP2-e2-del9 reduced the extent of interaction with FoxG1 to a level similar to that seen with Mecp2-e1 (Fig. 8,A or B).

Figure 8.

Analysis of interaction between FoxG1 and MeCP2–e2. A, Schematic representation of deletion construct of MeCP2–e2. B, Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of MeCP2–e2-del9-Myc with FoxG1. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with Flag antibody and immunoblotting (IB) was performed with Myc antibody. MeCP2–e2-del9-Myc does not interact with FoxG1-Flag like MeCP2–e2.

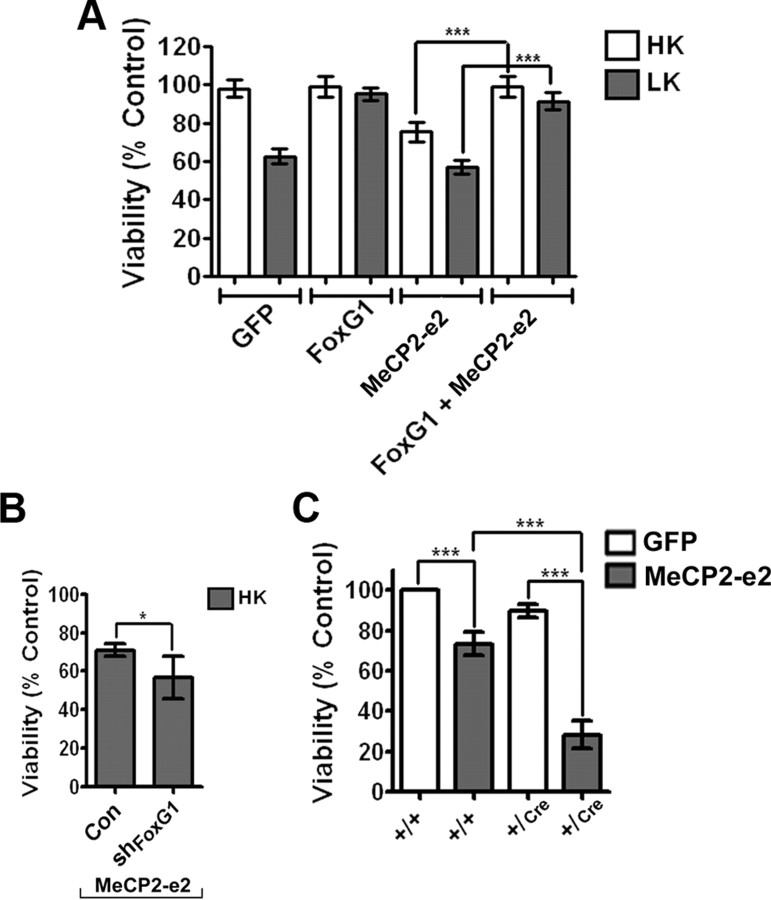

The established ability of FoxG1 to promote neuronal survival (Dastidar et al., 2011) along with our observation that it interacts with MeCP2-e2 raised the possibility that under normal circumstances the neurotoxic effect of MeCP2-e2 is inhibited by FoxG1 through direct association. To test this possibility, we examined whether forced expression of FoxG1 could inhibit the ability of MeCP2-e2 to induce neuronal death. As shown in Figure 9A, when coexpressed in neurons, FoxG1 completely blocks the neurotoxic effect of MeCP2-e2. If FoxG1 inhibits MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity, a reduction in the level of FoxG1 could be expected to enhance MeCP2-e2 toxicity. Indeed, shRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous FoxG1 expression increases the extent of MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity (Fig. 9B). Although the specificity of the FoxG1 shRNA was previously established (Dastidar et al., 2011), the possibility that the shRNA inhibited MeCP2 through the inhibition of another target could not be ruled out. To address this issue, we used a mouse line in which the FoxG1 gene is disrupted by insertion of Cre (Hébert and McConnell, 2000). Although mice homozygous for FoxG1 deletion die during gestation, FoxG1+/Cre mice are born, albeit with a smaller brain (Siegenthaler et al., 2008). To confirm that MeCP2-e2 toxicity is inhibited by FoxG1, we cultured CGNs from FoxG1+/Cre mice and control FoxG1+/+ littermates. As shown in Figure 9C, MeCP2-e2 toxicity was substantially increased in neurons cultured from FoxG1+/Cre mice compared with neurons from control littermates (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

MeCP2–e2 neurotoxicity is inhibited by FoxG1. A, Viability of CGNs transfected with GFP, FoxG1-Flag, and MeCP2–e2-GFP either by themselves or in combination and treated with HK or LK for 24 h. Viability was normalized to neurons transfected with GFP and treated with HK. FoxG1 can rescue against MeCP2–e2-mediated neuronal death. B, CGNs were cotransfected with MeCP2–e2 and either pLKO.1 (Con) or shFoxG1. The effectiveness of shFoxG1 (also referred to as #1746 in Dastidar et al., 2011) to suppress FoxG1 expression has previously been demonstrated (Dastidar et al., 2011). Viability of transfected cells identified by GFP immunoreactivity was quantified and compared with control shRNA and MeCP2–e2-GFP transfected neurons treated with HK. C, Viability of CGNs cultured from FoxG1+/+ and FoxG1+/Cre mice transfected with GFP or MeCP2–e2- GFP and treated with HK for 14 h. Viability was normalized to FoxG1+/+ CGNs transfected with GFP. Neurotoxicity is higher in neurons harvested from FoxG1+/Cre mice as compared with FoxG1+/+ neurons.

If FoxG1 inhibits Mecp2-e2 toxicity by interacting with it, expression of an MeCP2-e2 mutant incapable of interacting with FoxG1 could be expected to be more toxic. To examine this, we compared the toxicity of MeCP2-e2 with that of MeCP2-e2-del9, the deletion mutant that displays reduced interaction with FoxG1 (Fig. 8B). When expressed in CGNs, MeCP2-e2-del9 was more toxic that wild-type MeCP2-e2, consistent with a reduction in FoxG1-mediated repression of toxicity (Fig. 10A). We also expressed two FoxG1 deletion constructs that lacked the MeCP2-e2 binding site and would therefore be unable to inhibit MeCP2-e2 toxicity. Expression of FoxG1-1-191 or FoxG1-1-233 was also toxic (Fig. 10B). Although the inability to bind to MeCP2-e2 and sequester it might contribute to their toxic effect, it is also possible that these two FoxG1 mutants are unable to bind DNA efficiently. As described previously, DNA binding is essential for the survival-promoting effect of FoxG1 (Dastidar et al., 2011).

Figure 10.

MeCP2–e2 neurotoxicity is inhibited by FoxG1. A, Viability of neurons transfected with GFP, MeCP2–e2-Myc, and MeCP2–e2-del9-Myc and treated with HK for 24 h. Viability of neurons was normalized to CGNs transfected with GFP and treated with HK. MeCP2–e2-del9 killed healthy neurons more than MeCP2–e2. B, Viability of neurons transfected with GFP, FoxG1-1–191-Flag, and FoxG1-1–233- Flag and treated with HK for 24 h. Viability of neurons was normalized to CGNs transfected with GFP and treated with HK. Both the deleted constructs of FoxG1 killed neurons. C, RT-PCR analysis of HT22 cells transfected with FoxG1, GFP, and MeCP2–e2. Overexpression of FoxG1 did not affect endogenous mRNA levels of Mecp2, and similarly overexpression of MeCP2–e2 did not affect the endogenous mRNA levels of FoxG1.

Although our results are consistent with FoxG1 inhibiting Mecp2 neurotoxicity through interaction, given that both FoxG1 and Mecp2 are transcriptional regulators, it was possible that overexpression of FoxG1 was causing transcriptional changes in Mecp2-e2 levels or vice versa. However, we could not detect any transcriptional changes in Mecp2-e2 levels when FoxG1 was overexpressed nor any difference in FoxG1 levels when MeCP2-e2 was overexpressed (Fig. 10C).

IGF-1–Akt signaling inhibits neurotoxicity by Mecp2

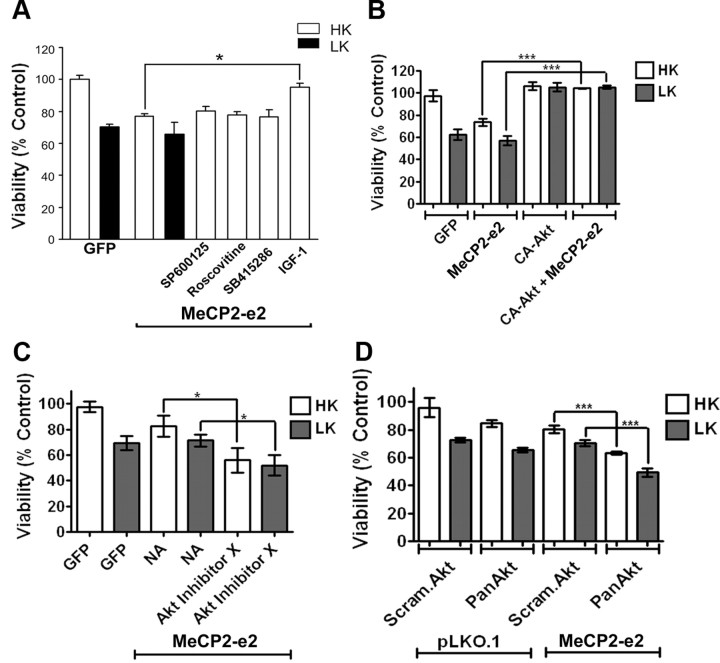

IGF-1 administration partially reverses the neurological phenotype in mutant Mecp2 mice (Tropea et al., 2009). We have previously shown that treatment of CGNs with IGF-1 blocks the LK-induced downregulation of FoxG1 expression and maintains neuronal survival (Dastidar et al., 2011). As shown in Figure 11A, treatment of neurons with IGF-1 also inhibits the toxic effect of MeCP2-e2. In addition to maintaining FoxG1 expression, IGF-1 treatment induces phosphorylation of FoxG1 at Ser271 through the activation of Akt, a modification that is necessary for the neuroprotective activity of FoxG1 (Dastidar et al., 2011). Consistent with FoxG1 being a negative regulator of MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity, forced expression of a constitutively active form of Akt inhibits the toxic effect of MeCP2-e2 (Fig. 11B). Conversely, reducing Akt activity pharmacologically using a chemical inhibitor, Akt Inhibitor X, or suppressing Akt expression using shRNA against Akt enhances MeCP2-e2-mediated neurotoxicity (Fig. 11C,D). A control experiment showed that AktX was able to block phosphorylation of Akt (data not shown). Activation of other kinases such as JNK, GSK3β, and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) is known to play a pivotal role in mediating neuronal death in different experimental paradigms. To examine whether any of these kinases are involved in MeCP2-e2-induced neuronal death, we used pharmacological inhibitors against them. Treatment with the JNK inhibitor (SP600125), the GSK3β inhibitor (SB415286), or the CDK inhibitor (roscovitine) did not inhibit MeCP2-e2-mediated neuronal death, suggesting that JNK, GSK3β, and CDKs are not involved (Fig. 11A). Control experiments confirmed that these compounds inhibited their targets at the doses that were used (data not shown).

Figure 11.

IGF-1 blocks MeCP2–e2-mediated neurotoxicity. A, Viability of CGNs transfected with GFP or MeCP2–e2- GFP and switched to HK or LK medium or LK medium supplemented with inhibitors (SP600125, roscovitine, or SB415286) or with IGF-1. Viability of transfected cells was quantified by DAPI staining and normalized to GFP-transfected cultures treated with HK (control). IGF-1 protected against MeCP2–e2-mediated neuronal death. B, Viability of CGNs transfected with GFP, MeCP2–e2-GFP, and CA-Akt-HA either by themselves or in combination and treated with HK or LK for 24 h. Viability was normalized to neurons transfected with GFP and treated with HK. CA-Akt can rescue against MeCP2–e2-mediated neuronal death. C, Viability of CGNs transfected with GFP or MeCP2–e2 and treated with HK or LK or HK or LK with Akt Inhibitor X. Viability of transfected neurons was normalized to GFP transfected neurons treated with HK. Blocking Akt increased MeCP2–e2 toxicity. D, Viability of CGNs cotransfected with pLKO.1 and either Scrambled Akt (Scram.Akt) or Pan Akt shRNA and MeCP2–e2 with either Scrambled Akt or Pan Akt shRNA. Viability was normalized to CGNs transfected with pLKO.1 and Scrambled Akt. Bringing down the levels of endogenous Akt increased MeCP2–e2-mediated neuronal death. NA, no additive.

Discussion

Although the MeCP2 protein can be expressed as two isoforms due to alternative splicing, the physiological significance of each of the two MeCP2 proteins has not been studied, and it is generally assumed that they are functionally equivalent. Indeed, most studies in which MeCP2 is ectopically expressed fail to specify which isoform is being used. We show that expression of the two isoforms is differentially regulated in neurons primed to die. Specifically, Mecp2-e2 expression is increased in CGNs and cortical neurons induced to die by LK or Aβ treatment, respectively, whereas the expression of Mecp2-e1 is slightly reduced. Furthermore, the two Mecp2 isoforms have distinct effects on the viability of neurons when overexpressed. Expression of MeCP2-e2 kills CGNs and cortical neurons, whereas MeCP2-e1 has no effect. Knockdown of the Mecp2-e2 isoform protects neurons from death consistent with the idea that elevated levels of Mecp2-e2 contribute to neuronal death. Our results appear to contradict those of another group who found that neurons cultured from Mecp2-null mice were more sensitive to excitotoxic and hypoxic-ischemic insult (Russell et al., 2007). In that study, overexpression of Mecp2 was found to partially reverse this vulnerability. Unfortunately, the Mecp2 isoform that was used in this analysis was not specified and it is possible that the e1 isoform was used.

Rett syndrome is caused by the loss of MeCP2 function (Chahrour and Zoghbi, 2007). Consistently, a Rett syndrome-like neurological phenotype is displayed in mice with reduced or no Mecp2 function (Chahrour and Zoghbi, 2007). Surprisingly. however, elevated MeCP2 expression resulting from gene duplication or triplication also causes neurological dysfunction in humans (Meins et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2005; Ariani et al., 2008). Likewise, transgenic mice expressing mildly elevated wild-type Mecp2 levels show significant neurological impairment (Collins et al., 2004; Luikenhuis et al., 2004). In transgenic lines generated by Collins et al. (2004), MeCP2 was overexpressed using a large genomic clone containing the entire MeCP2 locus. Mice homozygous for the Mecp2 transgene were born normal but then suffered seizures and ataxia, and died after 3–30 weeks, depending on the level of transgene expression. Another study reported the generation of a transgenic mouse line in which the e2 isoform was overexpressed specifically in postmitotic neurons by insertion of the Mecp2-e2 transgene into the tau gene locus (Luikenhuis et al., 2004). Gait ataxia and severe motor dysfunction were observed in these mice (Luikenhuis et al., 2004). Whether neurological dysfunction was accompanied by the loss of neurons was not reported in either of these two types of Mecp2-overexpressing mouse lines, and thus such a possibility cannot be excluded. Consistent with our conclusion that elevated expression of Mecp2-e2 is deleterious to neuronal viability is the finding of progressive cerebellar degeneration in humans with a duplication of the MeCP2 locus (Reardon et al., 2010).

Although other Mecp2-interacting proteins have been identified, we show for the first time that Mecp2 interacts with FoxG1, a protein that promotes the survival of postmitotic neurons (Dastidar et al., 2011). Several recent studies have found that mutations of FoxG1 also cause Rett syndrome (Ariani et al., 2008; Bahi-Buisson et al., 2010; Mencarelli et al., 2010). We find that FoxG1 inhibits the neurotoxic effect of MeCP2-e2. Overexpression of FoxG1 prevents MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity, whereas neurotoxicity is enhanced if FoxG1 expression is knocked down or in neurons cultured from FoxG1-deficient mice. Interaction is much higher with the e2 isoform, and this is explained by the finding that FoxG1 interacts primarily with the 9 aa sequence unique to the e2 isoform of MeCP2. An MeCP2-e2 mutant construct lacking this 9 aa region displays reduced interaction with FoxG1 and a higher level of neurotoxicity. Our data suggest that the FoxG1 inhibits Mecp2-e2 neurotoxicity by physically associating with it. Under apoptotic conditions, FoxG1 expression is severely reduced (Dastidar et al., 2011). Reduced FoxG1 expression would release Mecp2-e2 from its inhibition thereby allowing it to exert its neurotoxic effect.

More work is needed to delineate the mechanism by which the interaction between FoxG1 and Mecp2 inhibits Mecp2-e2 neurotoxicity. One possibility is that Mecp2-e2 neurotoxicity involves interaction with other pro-apoptotic molecules and that FoxG1 disrupts these interactions by sequestering Mecp2-e2. Sequestration of Mecp2-e2 could also prevent its ability to associate and repress promoters of genes encoding survival-promoting molecules, such as the BDNF gene. Repression of BDNF transcription by Mecp2 has previously been described (Chahrour et al., 2008). BDNF promotes the survival of a variety of neuronal types, including CGNs in culture, by activating PI-3 kinase–Akt signaling. Another neurotrophic factor that activates the PI-3 kinase–Akt pathway is IGF-1. Consistent with activation of PI-3 kinase–Akt signaling being a negative regulator of Mecp2-e2 neurotoxicity, the level of toxicity is reduced by IGF-1 treatment. We have previously demonstrated that through Akt activation, IGF-1 phosphorylates FoxG1 at Thr271, a modification that is required for the ability of FoxG1 to promote neuronal survival (Dastidar et al., 2011). Indeed, expression of active Akt also inhibits MeCP2-e2 neurotoxicity, whereas inhibition of endogenous Akt or suppression of its expression potentiates Mecp2-e2 toxicity. A previous study reported that IGF-1 administration partially reverses the Rett syndrome-like neurological phenotype in Mecp2 mutant mice (Tropea et al., 2009). It is tempting to speculate that this beneficial effect of IGF-1 in Rett mice involves the activation of FoxG1.

In summary, Mecp2-e2 promotes neuronal death, an action that can be inhibited by FoxG1. Mutations in both the MeCP2 and FoxG1 genes cause Rett syndrome. Based on the study of humans as well as Mecp2-deficient mouse models, it is generally agreed upon that Rett syndrome is not a neurodegenerative disorder. Our results suggest that a loss of Mecp2 function, specifically the e2 isoform, could potentially reduce the normal level of neuronal death rather than increase it. Consistent with this idea, duplication of the MeCP2 gene has been found to cause cerebellar degeneration in humans. Aside from the possible connection to Rett syndrome, our study links two molecules studied so far primarily in the context of neurodevelopment, to the regulation of neuronal survival and death. Furthermore, we report that Mecp2-e1 and Mecp2-e2 are regulated differentially during neuronal death, have different effects when expressed in neurons, and interact with FoxG1 differentially, demonstrating for the first time functional differences between the two Mecp2 isoforms.

Footnotes

This research was supported by Grants NS040408 and NS058462 from the National Institutes of Health (S.R.D.). We thank Jason Pfister for careful reading and reviewing of the manuscript and Lulu Wang for technical assistance.

References

- Ariani F, Hayek G, Rondinella D, Artuso R, Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, Pollazzon M, Buoni S, Spiga O, Ricciardi S, Meloni I, Longo I, Mari F, Broccoli V, Zappella M, Renieri A. FOXG1 is responsible for the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahi-Buisson N, Nectoux J, Girard B, Van Esch H, De Ravel T, Boddaert N, Plouin P, Rio M, Fichou Y, Chelly J, Bienvenu T. Revisiting the phenotype associated with FOXG1 mutations: two novel cases of congenital Rett variant. Neurogenetics. 2010;11:241–249. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardai FH, D'Mello SR. Selective toxicity by HDAC3 in neurons: regulation by akt and GSK3β. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1746–1751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5704-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF, Brouillet E, Jenkins BG, Ferrante RJ, Kowall NW, Miller JM, Storey E, Srivastava R, Rosen BR, Hyman BT. Neurochemical and histological characterization of striatal excitotoxic lesions produced by the mitochondrial toxin 3-Nitropropionic acid. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4181–4192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04181.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkblom B, Vainio JC, Hongisto V, Herdegen T, Courtney MJ, Coffey ET. All JNKs can kill, but nuclear localization is critical for neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19704–19713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707744200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfa G, Percy AK, Pozzo-Miller L. Experimental models of Rett syndrome based on Mecp2 dysfunction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:3–19. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong ST, Qin J, Zoghbi HY. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HL, D'Mello SR. Induction of neuronal cell death by paraneoplastic Ma1 antigen. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:3508–3519. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HM, Wang L, D'Mello SR. A chemical compound commonly used to inhibit PKR, {8-(imidazol-4-ylmethylene)-6H-azolidino[5,4-g] benzothiazol-7-one}, protects neurons by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinase. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:2003–2016. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin PC, Liu L, Morrison BE, Siddiq A, Ratan RR, Bottiglieri T, D'Mello SR. The c-raf inhibitor GW5074 provides neuroprotection in vitro and in an animal model of neurodegeneration through a MEK-ERK and akt-independent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2004;90:595–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AL, Levenson JM, Vilaythong AP, Richman R, Armstrong DL, Noebels JL, David Sweatt J, Zoghbi HY. Mild overexpression of MeCP2 causes a progressive neurological disorder in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2679–2689. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastidar SG, Landrieu PM, D'Mello SR. FoxG1 promotes the survival of postmitotic neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:402–413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2897-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Esteban M, Martin-Zanca D, Andres-Martin L, Almeida A, Bolaños JP. Inhibition of PTEN by peroxynitrite activates the phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt neuroprotective signaling pathway. J Neurochem. 2007;102:194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Mello SR, Galli C, Ciotti T, Calissano P. Induction of apoptosis in cerebellar granule neurons by low potassium: inhibition of death by insulin-like growth factor I and cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10989–10993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragich JM, Kim YH, Arnold AP, Schanen NC. Differential distribution of the MeCP2 splice variants in the postnatal mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:526–542. doi: 10.1002/cne.21264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escartin C, Boyer F, Bemelmans AP, Hantraye P, Brouillet E. IGF-1 exacerbates the neurotoxicity of the mitochondrial inhibitor 3NP in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2007;425:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante RJ, Kubilus JK, Lee J, Ryu H, Beesen A, Zucker B, Smith K, Kowall NW, Ratan RR, Luthi-Carter R, Hersch SM. Histone deacetylase inhibition by sodium butyrate chemotherapy ameliorates the neurodegenerative phenotype in Huntington's disease mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9418–9427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09418.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales ML, LaSalle JM. The role of MeCP2 in brain development and neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanashima C, Shen L, Li SC, Lai E. Brain factor-1 controls the proliferation and differentiation of neocortical progenitor cells through independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6526–6536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06526.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanashima C, Li SC, Shen L, Lai E, Fishell G. Foxg1 suppresses early cortical cell fate. Science. 2004;303:56–59. doi: 10.1126/science.1090674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert JM, McConnell SK. Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev Biol. 2000;222:296–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockly E, Richon VM, Woodman B, Smith DL, Zhou X, Rosa E, Sathasivam K, Ghazi-Noori S, Mahal A, Lowden PA, Steffan JS, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Lewis CM, Marks PA, Bates GP. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, ameliorates motor deficits in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2041–2046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob FD, Ramaswamy V, Andersen J, Bolduc FV. Atypical Rett syndrome with selective FOXG1 deletion detected by comparative genomic hybridization: case report and review of literature. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:1577–1581. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung BP, Jugloff DG, Zhang G, Logan R, Brown S, Eubanks JH. The expression of methyl CpG binding factor MeCP2 correlates with cellular differentiation in the developing rat brain and in cultured cells. J Neurobiol. 2003;55:86–96. doi: 10.1002/neu.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi N, Macklis JD. MECP2 is progressively expressed in post-migratory neurons and is involved in neuronal maturation rather than cell fate decisions. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriaucionis S, Bird A. The major form of MeCP2 has a novel N-terminus generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1818–1823. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guen T, Bahi-Buisson N, Nectoux J, Boddaert N, Fichou Y, Diebold B, Desguerre I, Raqbi F, Daire VC, Chelly J, Bienvenu T. A FOXG1 mutation in a boy with congenital variant of rett syndrome. Neurogenetics. 2011;12:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10048-010-0255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Popovic N, Brundin P. The use of the R6 transgenic mouse models of Huntington's disease in attempts to develop novel therapeutic strategies. NeuroRx. 2005;2:447–464. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.3.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luikenhuis S, Giacometti E, Beard CF, Jaenisch R. Expression of MeCP2 in postmitotic neurons rescues rett syndrome in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6033–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401626101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, D'Mello SR. Neuroprotection by histone deacetylase-7 (HDAC7) occurs by inhibition of c-jun expression through a deacetylase-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4819–4828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens M, Harper A, Hetherington C, Lawton M, Trottier Y, Lehrach H, Davies SW, Bates GP. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;87:493–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meins M, Lehmann J, Gerresheim F, Herchenbach J, Hagedorn M, Hameister K, Epplen JT. Submicroscopic duplication in Xq28 causes increased expression of the MECP2 gene in a boy with severe mental retardation and features of rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e12. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.023804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, Artuso R, Rondinella D, De Filippis R, Bahi-Buisson N, Nectoux J, Rubinsztajn R, Bienvenu T, Moncla A, Chabrol B, Villard L, Krumina Z, Armstrong J, Roche A, Pineda M, Gak E, Mari F, Ariani F, Renieri A. Novel FOXG1 mutations associated with the congenital variant of rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47:49–53. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnatzakanian GN, Lohi H, Munteanu I, Alfred SE, Yamada T, MacLeod PJ, Jones JR, Scherer SW, Schanen NC, Friez MJ, Vincent JB, Minassian BA. A previously unidentified MECP2 open reading frame defines a new protein isoform relevant to rett syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:339–341. doi: 10.1038/ng1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe C, Amsallem D, Francannet C, Lambert L, Saunier A, Verneau F, Jonveaux P. Phenotypic variability in rett syndrome associated with FOXG1 mutations in females. J Med Genet. 2010;47:59–65. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon W, Donoghue V, Murphy AM, King MD, Mayne PD, Horn N, Birk Møller L. Progressive cerebellar degenerative changes in the severe mental retardation syndrome caused by duplication of MECP2 and adjacent loci on Xq28. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:941–949. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JC, Blue ME, Johnston MV, Naidu S, Hossain MA. Enhanced cell death in MeCP2 null cerebellar granule neurons exposed to excitotoxicity and hypoxia. Neuroscience. 2007;150:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Shibayama A, Liu Q, Nguyen VQ, Feng J, Santos M, Temudo T, Maciel P, Sommer SS. Detection of heterozygous deletions and duplications in the MECP2 gene in rett syndrome by robust dosage PCR (RD-PCR) Hum Mutat. 2005;25:505. doi: 10.1002/humu.9338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegenthaler JA, Tremper-Wells BA, Miller MW. Foxg1 haploinsufficiency reduces the population of cortical intermediate progenitor cells: effect of increased p21 expression. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:1865–1875. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao W, Lai E. Telencephalon-restricted expression of BF-1, a new member of the HNF-3/fork head gene family, in the developing rat brain. Neuron. 1992;8:957–966. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropea D, Giacometti E, Wilson NR, Beard C, McCurry C, Fu DD, Flannery R, Jaenisch R, Sur M. Partial reversal of rett syndrome-like symptoms in MeCP2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2029–2034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812394106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ankati H, Akubathini SK, Balderamos M, Storey CA, Patel AV, Price V, Kretzschmar D, Biehl ER, D'Mello SR. Identification of novel 1,4-benzoxazine compounds that are protective in tissue culture and in vivo models of neurodegeneration. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:1970–1984. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan S, Baptista CA, Balas G, Tao W, Soares VC, Lai E. Winged helix transcription factor BF-1 is essential for the development of the cerebral hemispheres. Neuron. 1995;14:1141–1152. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui DH, Peddada S, Bieda MC, Vallero RO, Hogart A, Nagarajan RP, Thatcher KN, Farnham PJ, Lasalle JM. Integrated epigenomic analyses of neuronal MeCP2 reveal a role for long-range interaction with active genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19416–19421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707442104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]