Summary

The solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) has always been a diagnostic challenge for the radiologists. Currently, with increased utilization of computed tomography (CT) greater number of nodules is being discovered, with numerous indeterminate lesions, which frequently cannot be immediately classified into benign or malignant category.

In this article we review the imaging features of benign and malignant round opacities; we demonstrate currently used standards and also more advanced techniques that are helpful in evaluating SPNs such as contrast-enhanced CT, PET/CT imaging and also pathologic sampling with biopsy or surgical resection.

We also summarize the methods of evaluating and managing SPNs based on the latest guidelines from the Fleischner Society and American College of Chest Physicians.

Keywords: solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN), multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT), indeterminate nodule, transthoracic needle biopsy (TNB)

Background

The solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) has always been a diagnostic challenge for the radiologists. According to the Fleischner Society a radiological definition of a solitary pulmonary nodule is „a round opacity, at least moderately well-marginated and up to 3 cm in maximum diameter” [1]. Additionally, some authors use a term „small nodule” to distinguish a lesion which has a diameter less than 1 cm [1]. On the other hand a focal pulmonary lesion which is greater than 3 cm in diameter is called “a lung mass” and is expected to be a bronchogenic carcinoma until proven otherwise [2].

Nowadays with increased utilization of computed tomography (CT) greater numbers of nodules are being discovered which fall into indeterminate category. According to the American College of Chest Physicians the term “indeterminate” describes a nodule that does not show a benign pattern of calcifications and has not been stable in size after >2 years of follow-up [2], therefore cannot be immediately categorized into benign or malignant group.

The current role of diagnostic imaging is to try to determine in the most precise matter whether a discovered SPN is benign or malignant in order to plan further management. However, despite some features that can help with this differentiation, still a large number of nodules have to be described as “indeterminate” and advanced and often more invasive techniques might be needed for further work-up.

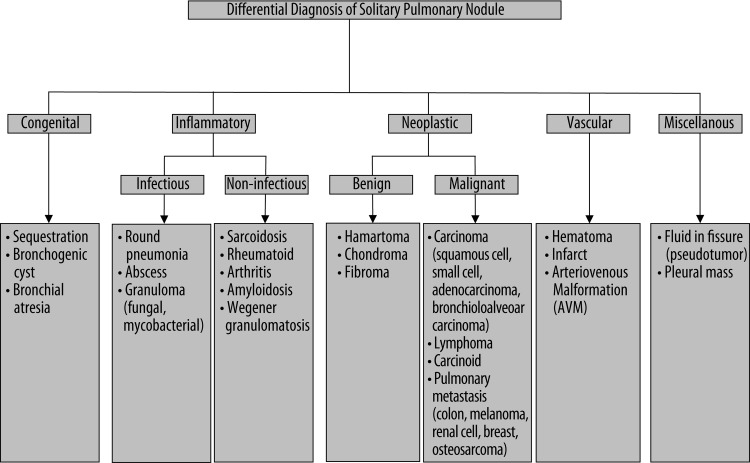

The differential diagnosis for a SPN is very broad and the brief summary of the most common causes is shown in Figure 1 [3,4].

Figure 1.

The differential diagnosis for a solitary pulmonary nodule [3,4].

In this article we review the imaging features of benign and malignant focal pulmonary opacities and we also endeavor to summarize the methods of evaluating and managing SPNs based on the latest guidelines from the Fleischner Society and the American College of Chest Physicians.

Characteristics of a Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

Size

The size of incidentally found SPN can help in differentiating between benign and malignant lesions. Generally nodular opacities with diameter greater than 3 cm (currently termed lung masses) have much higher probability of being malignant [5,6]. On the other hand smaller lesions, less than 2 cm in diameter, are more often benign [3]. According to one study from Mayo Clinic, less than 1% of nodules with diameter of 4 mm or less have turned out to be malignant [5,7]. Despite these basic presumptions the growing application of MDCT performed for different reasons, increased the number of smaller SPNs that are incidentally discovered. Some of those nodules with diameter equal to or even less than 1 cm are malignant lesions detected in their earlier stages [8]. Nonetheless, the positive relationship of the lesion size to likelihood of malignancy has been reliably shown in several recent studies [9,10].

Margin characteristics

Benign lesions are more likely to have smooth, well-marginated borders (Figure 2). On the other hand malignant nodules usually have ill-defined, irregular (Figure 3) or lobulated (Figure 4) contours [11]. But still there is a significant overlapping between these findings. Nodules with spiculated borders (due to malignant cells extending within pulmonary interstitial tissue) (Figure 5), sometimes termed as a “corona radiata” or “sunburst” are highly suspicious for malignancy but the similar appearance can also represent benign infectious/inflammatory lesion [11]. Lobulated contours of a lesion, which are thought to be caused by uneven growth within a nodule, are more frequently associated with malignant pathology but are found also in benign nodules [12]. On the contrary smooth margins and well-defined borders cannot exclude malignancy because up to 20% of primary lung cancers and most of the metastatic nodules can present with that appearance [12,13].

Figure 2.

Well-circumscribed pulmonary nodule with smooth margins.

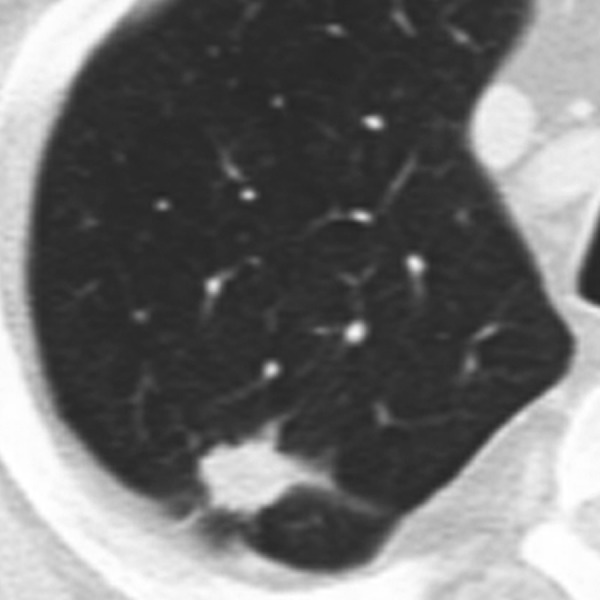

Figure 3.

Pulmonary nodule with irregular margins.

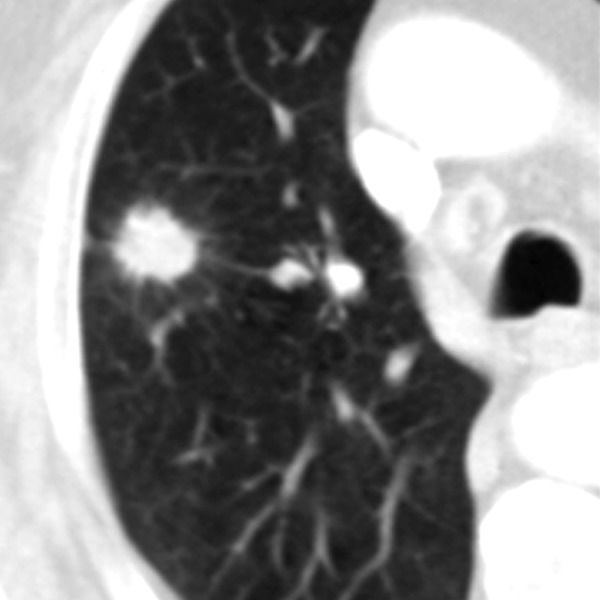

Figure 4.

Pulmonary nodule with lobulated margins.

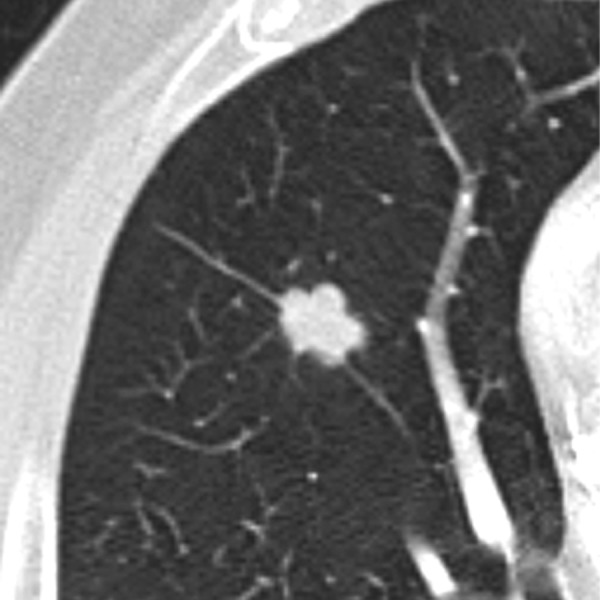

Figure 5.

Pulmonary nodule with spiculated margins and „halo sign”.

Internal characteristics

Some internal features of SPNs can help in differentiating benign from malignant lesions.

The presence of particular types/patterns of calcification within a nodule can help to distinguish a benign lesion from a malignant one. The best imaging tool to detect intranodular calcification is thin-section CT (without contrast enhancement) which is more sensitive than standard radiography and also allows for quantitative assessment of calcification [3]. Other methods that can be used to evaluate the presence of calcifications are low-kilovoltage radiography and chest fluoroscopy, but overall thin-section MDCT is the method of choice. The benign patterns of calcifications commonly involve: central, diffuse solid, laminated (Figure 6) and “popcorn-like” appearance. The first three types usually represent the granulomas of various origin [14] and can be associated with prior infections, for example histoplasmosis (Figures 7, 8) or tuberculosis [3]. The last pattern – “popcorn-like” calcifications is diagnostic for hamartoma [15]. Unfortunately, sometimes the lung metastases from chondrosarcomas or osteosarcomas can demonstrate “benign-patterns” of calcification [16,17]. This is where the clinical history is very important and can help make the correct diagnosis. Calcifications can also be detected in malignant lesions, in up to 13% of cancers [18] and 33% of carcinoids [19]. Malignancies usually tend to present different patterns of calcifications, such as amorphous, stippled or eccentric (Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Benign granuloma with characteristic laminated pattern of calcification.

Figure 7.

Benign pulmonary nodule with central calcification due to prior histoplasma infection.

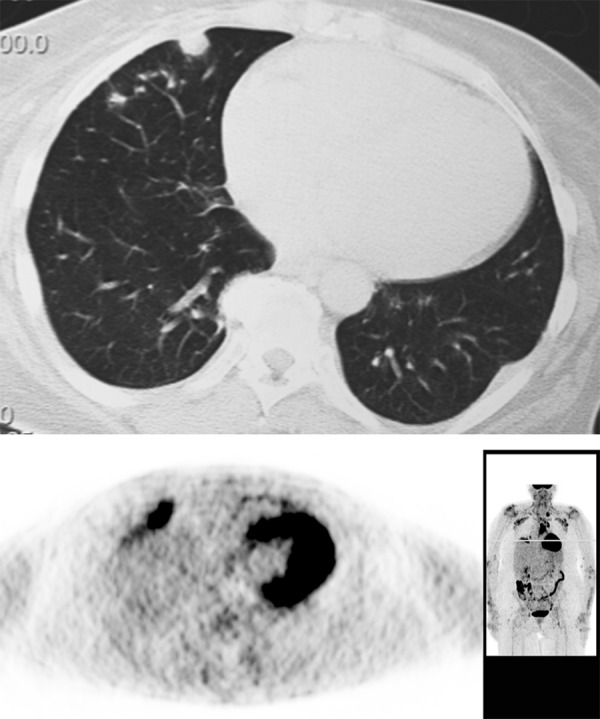

Figure 8.

Histoplasmosis. Pulmonary nodule in CT and PET-CT. Note that the nodule is non FDG avid.

Figure 9.

Pulmonary nodule with malignant pattern of calcification.

The presence of fat within a lesion is a pathognomonic feature of hamartoma (Figure 10). It can be detected on CT, based on the attenuation values between −40 to −120 HU, in up to 50% of these benign neoplasms [15]. However, although very rare, sometimes lung metastases from renal cell cancer or liposarcoma can present as fat-containing lesions [11,16].

Figure 10.

Benign hamartoma.

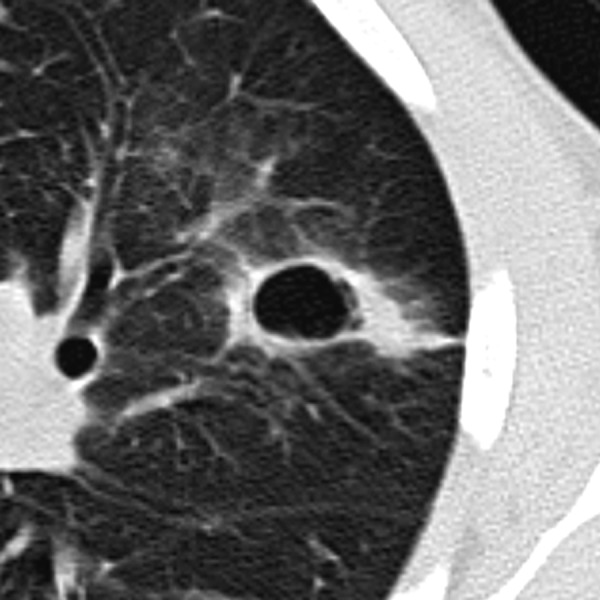

Some pulmonary nodules can demonstrate cavitary appearance. Cavitations can be present in infectious or inflammatory lesions (Figure 11) as well as in primary and metastatic malignancies; up to 15% of primary lung cancers cavitate, mostly of squamous cell pathology (Figures 12, 13) [11]. Although the presence of cavitation itself is not a strong differentiating factor, the appearance and thickness of a cavity wall can play useful role in diagnosis. Benign cavities tend to have smooth, thin walls, usually less than 4 mm at its broadest point, whereas nodules containing cavities with irregular, thick walls (exceeding 16 mm) have been found to be malignant in up to 95% of cases [20,21]. Overall, the thickness of a cavity wall within a nodule might add some value in assessing a lesion but cannot reliably differentiate between benign and malignant etiology. Woodring et al. have shown that cavitary nodules with wall thickness between 5–15 mm were found to be benign (51%) and malignant (49%) signifying that in this range there is a “gray-zone”[11,20].

Figure 11.

Benign cavity with relatively smooth, thin walls. This infectious lesion nearly resolved on follow-up imaging.

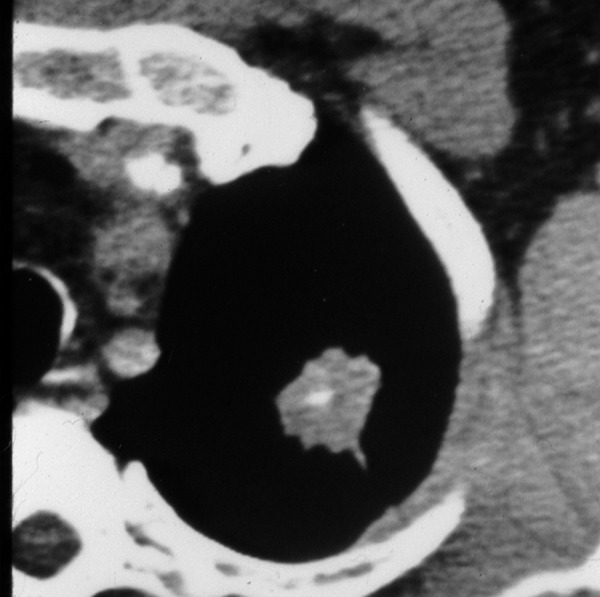

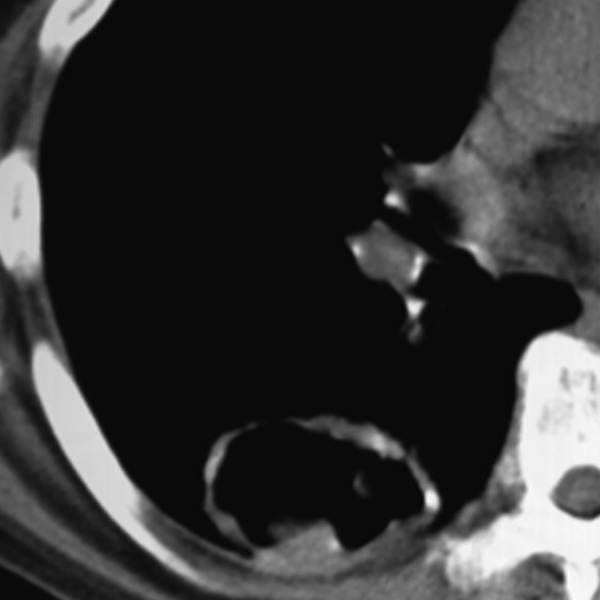

Figure 12.

Metastatic cavitary nodule due to squamous cell carcinoma.

Figure 13.

Cavitary squamous cell carcinoma. Note ring-like FDG avid lesion on PET-CT.

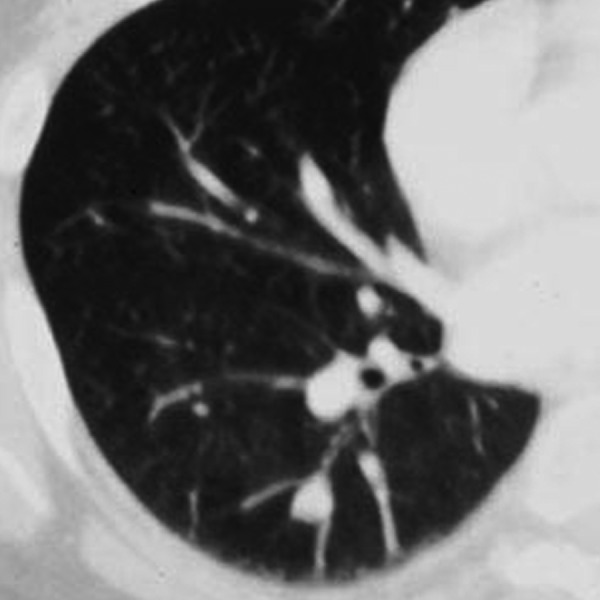

Other findings that can help in assessing a benign or malignant potential of a focal lesion include the presence of air bronchograms/bronchiolograms, cystic luciencies or so called satellite nodules [11]. Air bronchogram is usually seen in benign cases of focal infection, for example round pneumonia, but can also implicate the possibility of bronchioalveolar carcinoma or lymphoma. The involvement of a peripheral bronchus by a SPN often implicate a malignant potential (i.e. carcinoid tumor (Figure 14) or bronchogenic carcinoma). This can present on CT images as an endobronchial filling defect or peripheral hyperlucency of air trapping distal to the lesion. On the other hand, benign lesions very rarely have their origin inside the bronchus [5]. A cluster of small nodules (3–15 mm in diameter) within a segment or subsegment of the lung is usually caused by a granulomatous process, such as infection or sarcoidosis [5]. When there is a dominant bigger nodule surrounded by a group of small nodules the term “satellite nodules” can be used, which is also associated more frequently with benign potential, although sometimes lung cancer can present in similar way [11].

Figure 14.

Carcinoid.

Subsolid lesions

Slightly different approach is required when it comes to so called “subsolid” nodules. In addition to soft tissue component they contain also an element of ground-glass attenuation (partly solid) or consist of only ground-glass opacity (Figure 15A–C). In their study conducted as a part of Early Lung Cancer Action Project (ELCAP), Henschke et al. showed [22] the importance of these types of opacities. According to the study the incidence of malignancy in subsolid lesions was about 34% in comparison to solid nodules where it was estimated as only 7%. Among the subsolid lesions, partly solid nodules had the highest frequency of malignancy (63%) and pure ground-glass opacities about 18%. These types of lesions involve the pathologies ranging from atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (premalignant state) to bronchioalveolar carcinoma and invasive adenocarcinoma [11]. A higher potential for malignancy of subsolid nodules combined with their unique features (slow growth, relative hypometabolism and nonspecific cytologic and histologic findings) can make them a diagnostic challenge and usually they require a different management than solid SPN [5]. Currently several studies [23,24,25] are conducted that focus on this specific type of nodule and try to analyze its imaging features in relation to potential malignant or benign character.

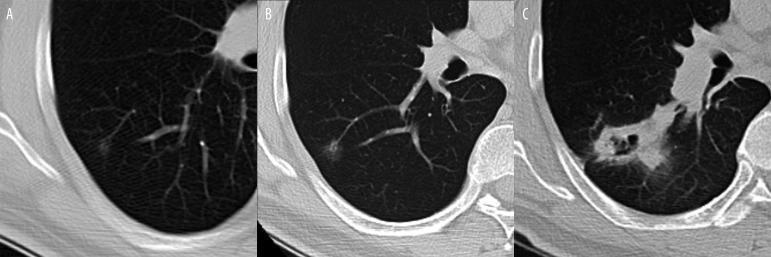

Figure 15.

Slowly growing malignancy from a ground glass nodule to a cavitary mass over 7 years: (A). 5 mm at baseline, (B) 10 mm 3 years later, (C) cavitary mass at diagnosis 4 years later – poorly differentiated sarcomatoid carcinoma.

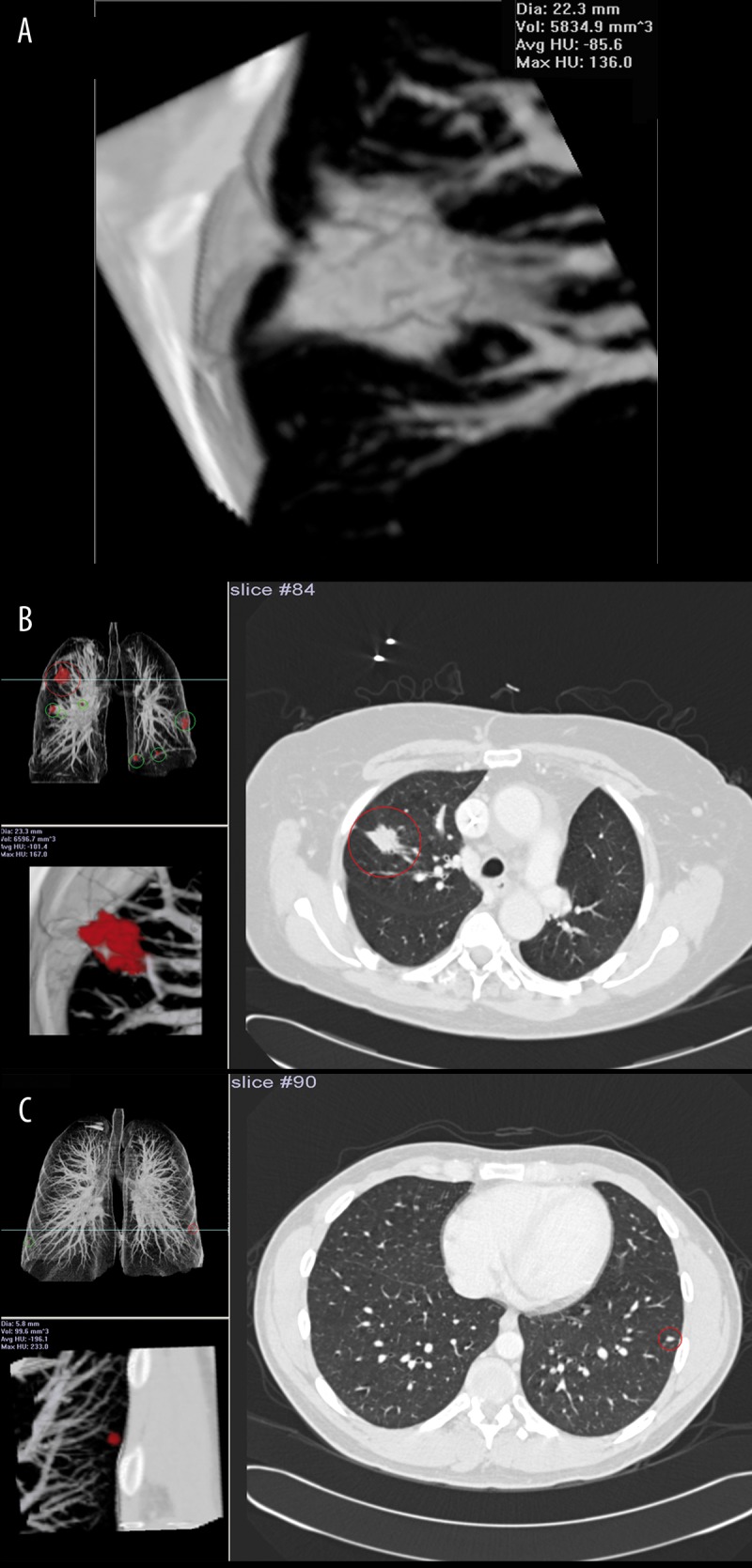

Growth pattern

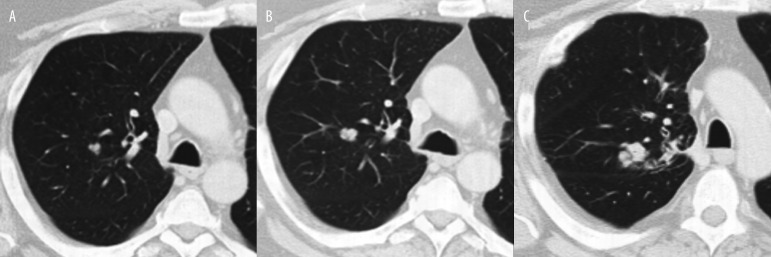

Until recently one of the most reassuring features of incidentally found SPN was stability in the size of the nodule for at least 2 years by comparing with prior exams. This finding was recognized as one of a few definitive criteria for benignity of the lesion. However this notion has been questioned [26]. Schwartz [27] explained, using mathematical principles, that smaller nodules appear to be growing slower because of smaller incremental increases in diameter. Consequently this was one of the reasons that computerized determinations of volume have been proposed as better tools for growth rate determination than diameter measurements [28]. More up-to-date viewpoint states that benign lesions usually grow very fast or very slowly, resulting in nodule volume doubling times (VDTs) of less than 30 or more than 400 days [29]. The lesions that grow very rapidly are usually infectious/inflammatory. The ones growing much slower are usually benign neoplasms like hamartomas or old post-infectious granulomas. Most of the malignant lesions have VDTs between 30 and 400 days (Figure 16A–C), but still a lot of overlap can be observed; for example subsolid lesions, including some forms of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma or bronchioalveolar carcinoma double in volume very slowly with VDT up to 1346 days [11,30]. In recently published study, Henschke et al. reviewed the distribution of VDTs of lung cancers diagnosed in repeat annual CT screening check-ups in the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP). The authors took into consideration both rates of tumor growth as well as cell types of the malignancy. From 111 cases identified as a primary lung cancer, median VDT was 98 days. For 56 (50%) cancers it was less than 100 days, and for three (3%) cancers it was more than 400 days. The most common type of cancer was adenocarcinoma (50%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (19%), small cell carcinoma (19%) and others. 99 of the 111 cancers demonstrated as solid nodules (of all cell types), and only 12 manifested as subsolid lesions (exclusively adenocarcinomas). Lung cancers appearing as subsolid nodules were found to have significantly longer VDTs than solid lung cancers. The main conclusion of the study was that VDTs of lung cancers identified by CT screening and of those detected incidentally in the absence of screening, are quite similar [31].

Figure 16.

Moderately differentiated lung carcinoma: (A) baseline, (B) 10 months later, (C) 6 months later.

Previous imaging studies including CT scans, chest radiographs or other should be obtained for comparison whenever it is possible. The size stability of a nodule versus the growth of a nodule are crucial parameters that have significant impact on further recommendations. For this reason the assessment has to be as accurate as possible. In recent years many studies [32–35] have been conducted to investigate this topic. They involve not only a subjective assessment of a pulmonary nodule by a radiologist but also evaluate new methods such as computer-aided diagnosis or detection (CAD) programs that could be employed in an attempt to make the assessment of a SPN more precise and accurate.

Sometimes the localization of a nodule can give us some clues in regards to its malignant or benign character. For example in the study conducted by Ahn et al. [36] authors have shown that noncalcified lung nodules that are adjacent to fissures can be often found in current or former smokers. Although these nodules may show worrisome increase in size, their potential for malignancy is low. Subpleural pulmonary nodules, especially in the middle and lower lobes of the lungs, may turn out to be intrapulmonary lymph nodes. Although in most cases benign, it is usually difficult to assess their benign or malignant character, based just on their imaging features. That is why a thoracoscopic procedure may be needed to make the final diagnosis [37,38].

It is also important to mention that all imaging findings should be correlated with the clinical symptoms of the patient. It is crucial to assess the presence of potential risk factors for malignancy which in case of lung cancer include: older age, current or past smoking history, exposure to carcinogens (asbestos, uranium or radon) or presenting initial symptoms [12]. Clinical symptoms, for example hemoptysis implicate higher probability of malignancy. On the other hand, patient presenting with fever, signs of respiratory infection and new focal lung opacity probably requires only radiological follow-up in order to make a diagnosis of benign round pneumonia [11]. Also, past medical history (prior malignancy) and family history (a history of lung cancer in first-degree relatives) can be helpful in overall evaluation.

Despite the ability of thin-section MDCT to evaluate SPNs with fine details, classification of SPNs into benign or malignant category remains difficult, even when the clinical presentation and clinical history are taken into consideration. A lot of SPNs display overlapping features. Those indeterminate nodules require additional diagnostic management, often with the use of more sophisticated or invasive techniques, in order to obtain additional information.

In the second part of this article we present more advanced steps in assessing the indeterminate pulmonary nodule which can help in making the final diagnosis and then in planning the most appropriate management.

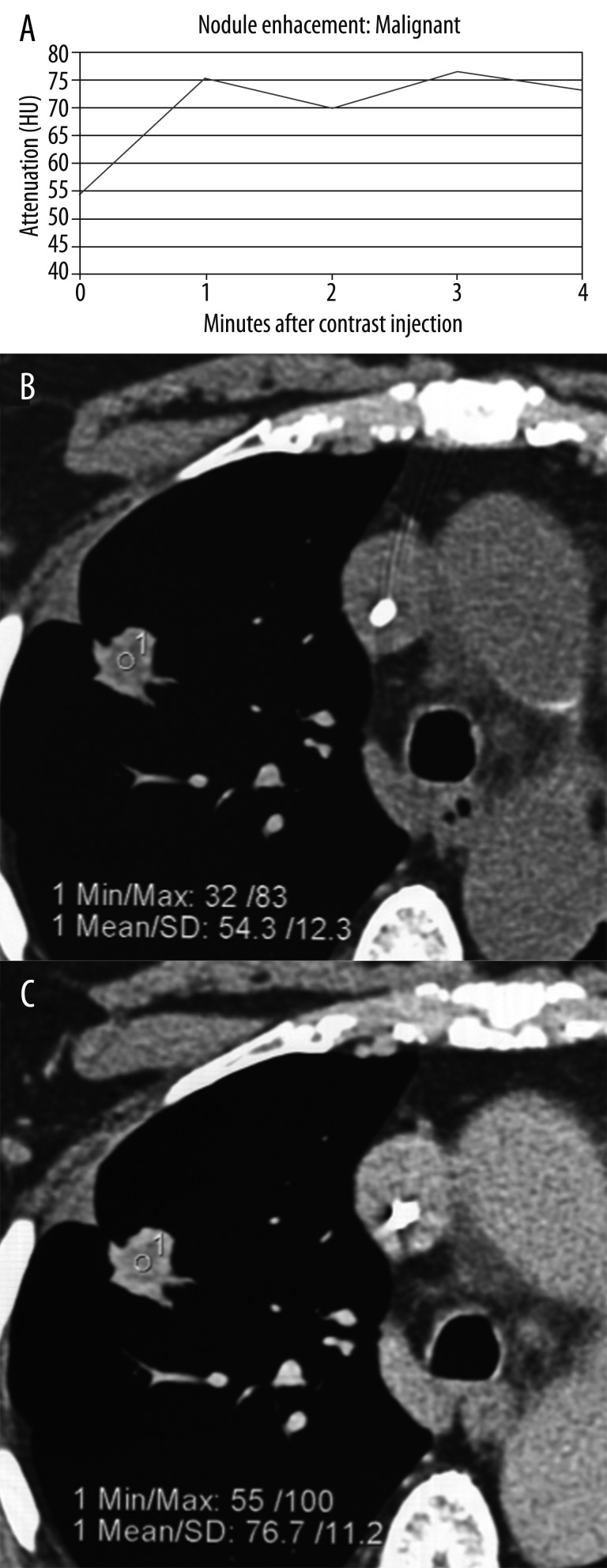

Contrast-enhanced MDCT

It has been documented that there are differences in perfusion between benign and malignant lesions which can be assessed with contrast-enhanced CT as a method to distinguish between the two etiologies. The observation that malignant tumors are generally relatively more hypervascular in comparison to benign lesions and the intensity of enhancement is directly related to the vascularity led to the conclusion that the stronger the enhancement the more malignant potential of the nodule (Figure 17A–C). The multicenter prospective trial concluded that enhancement values of 15 HU or less can be used as a diagnostic cut-off for benign lesion [39]. This enhancement cutoff of 15HU resulted in an excellent sensitivity of 98% but unfortunately it was not very specific for malignancy, only about 50–60% [39]. The general conclusion based on this report was that benign lesions usually enhance no more than 15 HU, whereas most of the malignant nodules develop more intensive enhancement, usually over 20 HU. There are some notable limitations of this study; the ideal size of the nodule should range between 5 mm and 3 cm in diameter, it should be spherical in shape and with homogenous attenuation (no fat, calcifications, cavitation or necrosis). In a different study by Yi et al. [40] with the enhancement cut-off of 30 HU, sensitivity for malignant nodules was 99% with a negative predictive value of 97%. The authors concluded that dynamic enhancement with MDCT shows high sensitivity for detection of malignant lesions but low specificity which probably is caused by the ability of some benign nodules to enhance intensely as well. The other conclusion was that the extent of enhancement reflects underlying nodule angiogenesis. In the more recent study the evaluation of SPNs using dynamic contrast-enhanced MDCT was conducted by analyzing combined criteria for malignancy including wash-in of contrast medium of 25HU or greater and washout of 5–31 HU on 15-minute-delayed imaging [41]. The results of this study show high sensitivity (94%), specificity (90%) and accuracy (92%) for detection of malignancy [41]. There were also some false negative results which included adenocarcinomas with bronchioalveolar carcinoma features and some false positives such as focal pneumonia and other infectious or inflammatory benign nodules.

Figure 17.

Pattern of malignant enhancement: (A) plot of nodule enhancement over time, (B) attenuation of the nodule before contrast administration, and (C) post-contrast enhancement.

One of the new ideas being investigated is the usage of a CAD to detect and differentiate malignant from benign nodules. CAD can analyze quantitative features (nodule’s size, shape, attenuation and enhancement) extracted from volumetric thin section CT image data acquired before and after the injection of contrast media (Figure 18A–C). The study conducted by Shah and colleagues [42] show that CAD using volumetric and contrast-enhanced data can be useful in distinguishing between benign and malignant lesion [11]. The preliminary results are promising, however additional studies are needed to validate these findings.

Figure 18.

Computer-aided detection/diagnosis (CAD) system R2: (A) volume calculation of the nodule, (B) system detected spiculated mass in the right lung, (C) tiny nodule detected in the left lung.

PET/CT Scanning

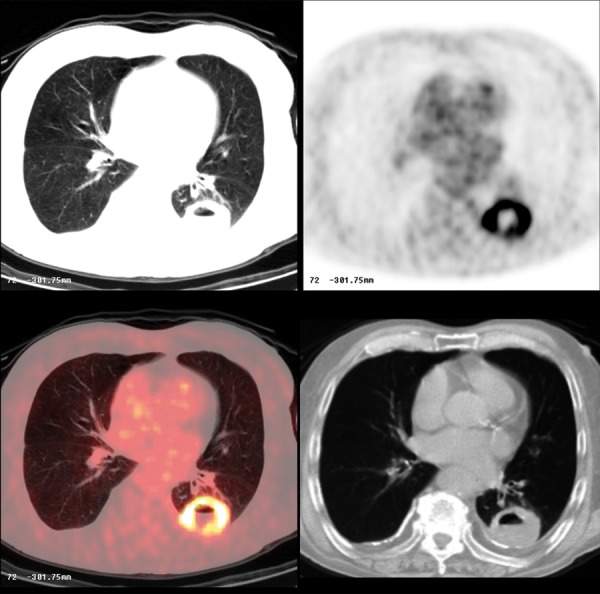

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanning can be another option to use in order to differentiate between benign and malignant pulmonary nodules. This technique is based on functional imaging and uses 18-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) to measure glucose metabolism within the cells. Glucose metabolism has been shown to be increased in malignancies with resulting increased uptake, trapping, and accumulation of FDG (Figures 19, 20). Introduced relatively recently PET/CT scanners combine CT and FDG imaging capabilities in a single patient gantry. Such hybrid devices help in determining the accurate localization of the areas of FDG uptake in regards to normal anatomic structures or abnormal soft-tissue masses [2]. This fusion technology also demonstrates the best results for staging malignancy [43]. According to one study PET/CT has a high sensitivity of approximately 97% with a slightly lower specificity of about 78% when it comes to detection of malignant pulmonary nodules with diameter greater than 10 mm [44]. PET images may be analyzed qualitatively by visual assessment or semiquantitatively by standardized uptake values (SUV). With visual assessment, a nodule is positive if its activity is greater than background mediastinal or cardiac blood pool activity. If a nodule activity is less than or equal to background activity, it is considered hypometabolic (negative). SUV is defined as a mean region of interest (ROI) activity (mCi/ml) divided by injected dose (mCi) over body weight (g). SUV is considered positive at a value equal to or greater than 2.5, resulting in a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 82% [45]. Unfortunately false positives and false negatives can occur. Acute infectious and inflammatory diseases like granulomatous processes, e.g. sarcoidosis (Figure 21), aspergillomas (Figure 22), or rheumatoid nodules (Figure 23) that can present as SPNs are capable of producing false positive results [46]. On the contrary false-negatives include bronchioalveolar carcinoma (BAC) (Figure 24), carcinoid tumors and mucinous adenocarcinomas (Figure 25). PET/CT not only has potential for uncovering the malignancy, but also has other roles in patient management, such as staging, evaluation of a response to therapy and detection of recurrence. The results of PET scanning also often determine further approach to the management to SPN [5,47]. PET imaging appears to be the best evaluation method for patients with low or intermediate pretest probability for malignancy and the nodule with diameter of 10 mm or more. On the other hand people with very low (< 5%) or very high (> 80%) pretest probability of malignancy generally benefit less from PET [5].

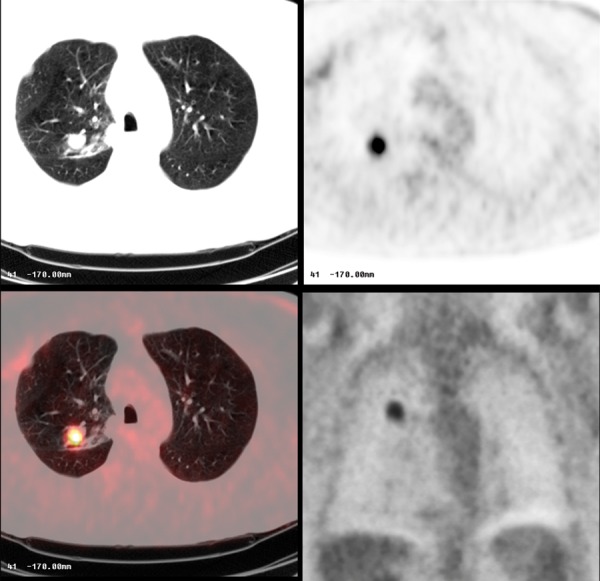

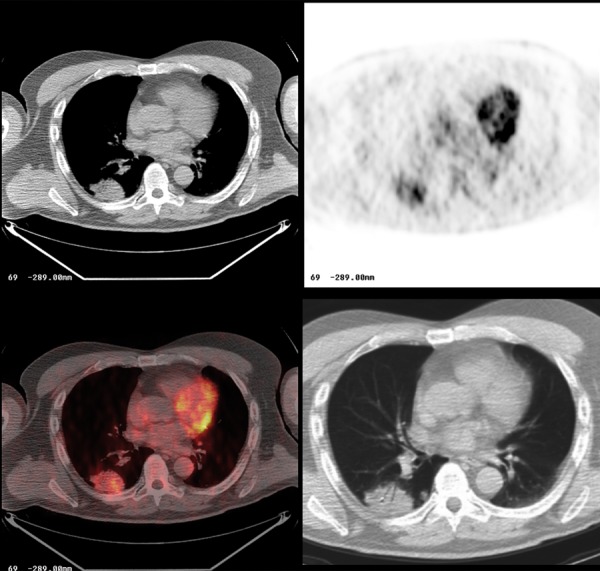

Figure 19.

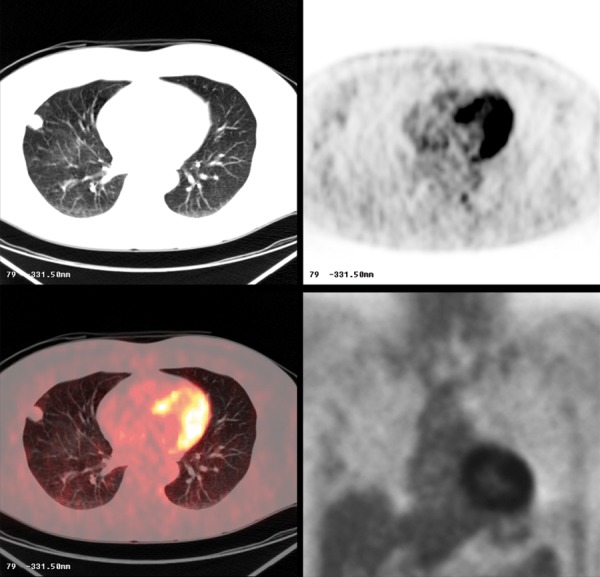

Moderately-differentiated lung carcinoma with FDG-avid lesion on PET-CT.

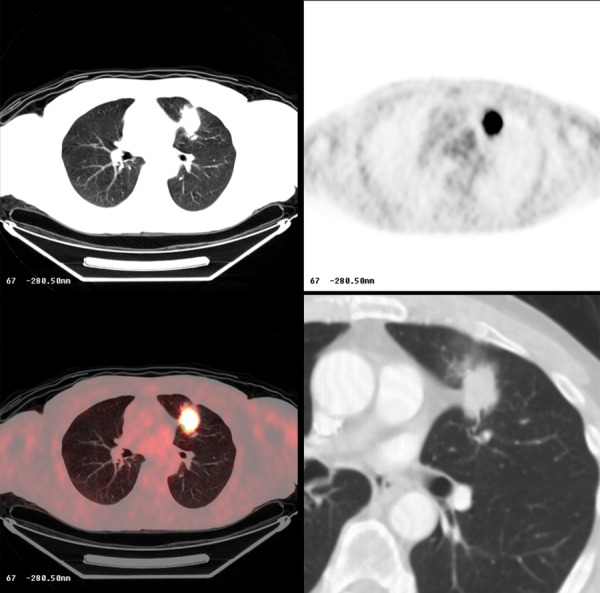

Figure 20.

Poorly-differentiated lung carcinoma with FDG-avid lesion on PET-CT.

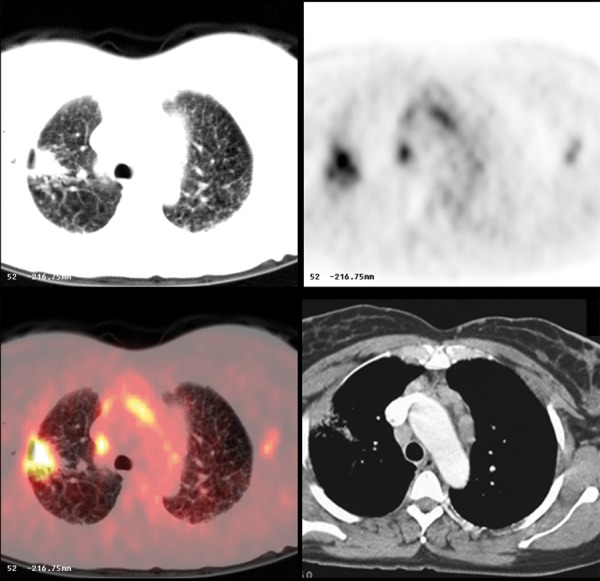

Figure 21.

FDG avid inflammatory lesion in the right lung and mediastinal and hilar adenopathy in pulmonary sarcoidosis.

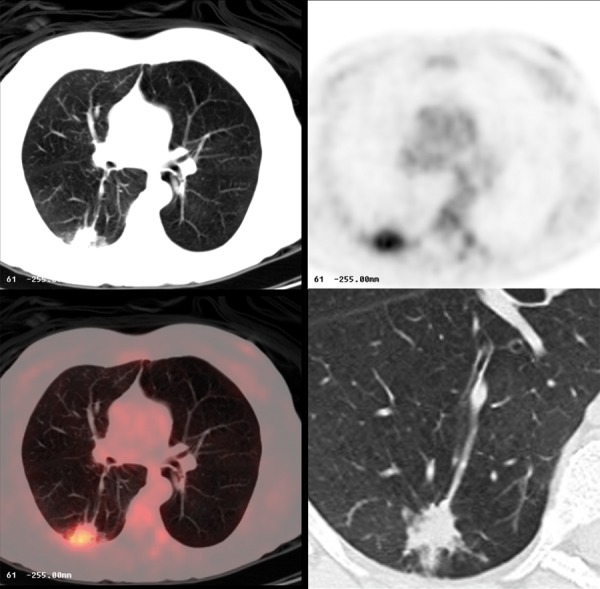

Figure 22.

Aspergilloma in the right lung with FDG avid lesion on PET-CT.

Figure 23.

Peripheral pulmonary nodule due to rheumatoid arthritis. Note FDG avid inflammatory nodule on PET.

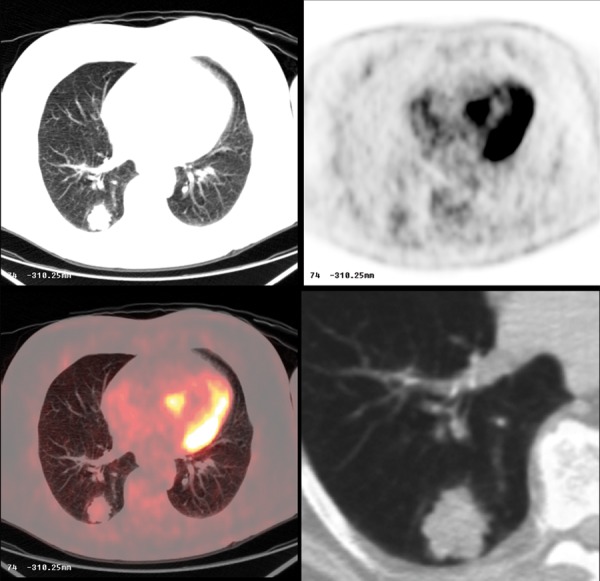

Figure 24.

Bronchioalveolar carcinoma in the right lung. Note mild, heterogeneous FDG avidity on PET-CT.

Figure 25.

Metastatic pulmonary nodule from a colorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Note minimal FDG avidity on PET-CT.

Other Techniques

The most definite tests to confirm either benign or malignant character of the pulmonary lesion are those which provide pathologic samples. Those procedures include: image-guided transthoracic needle biopsy (TNB), bronchoscopic biopsy, video-assisted thoracoscopy and open thoracotomy. The results of TNB and bronchoscopy are dependent on the size and location of the nodule and also on skills of a person performing the procedure. All those case and operator related factors influence the sensitivity and specificity of these methods. TNB can be performed under fluoroscopic, sonographic or CT control. Dependent on the gauge of the needle, a cytologic or histologic specimen can be taken for further analysis. An additional material for stains and cultures when infection is suspected can also be obtained. The most common complication after TNB involve pneumothorax, hemorrhage and systemic air embolism [48,49]. The American College of Chest Physicians recommends TNB as a first choice for patients with peripheral nodules, unless specific contraindications to the procedure exist or the nodule is inaccessible [2]. Bronchoscopic biopsy, on the other hand, is suggested when an air bronchogram is present within the lesion or when the lesion abuts the bronchus [2].

Management

In recent years several large lung cancer screening programs have been conducted [50–53]. Their main goal has been to establish the most effective strategy for screening. Early detection of lung cancer is important as this malignancy is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) [50], a multi-center study, focused on comparing low-dose helical CT with chest radiography in the evaluation of current and former heavy smokers (high-risk patients) for early detection of lung malignancy. Recently published results revealed that participants who received low-dose helical CT had a 20% lower risk of dying from lung cancer than participants who received standard chest radiography [54].

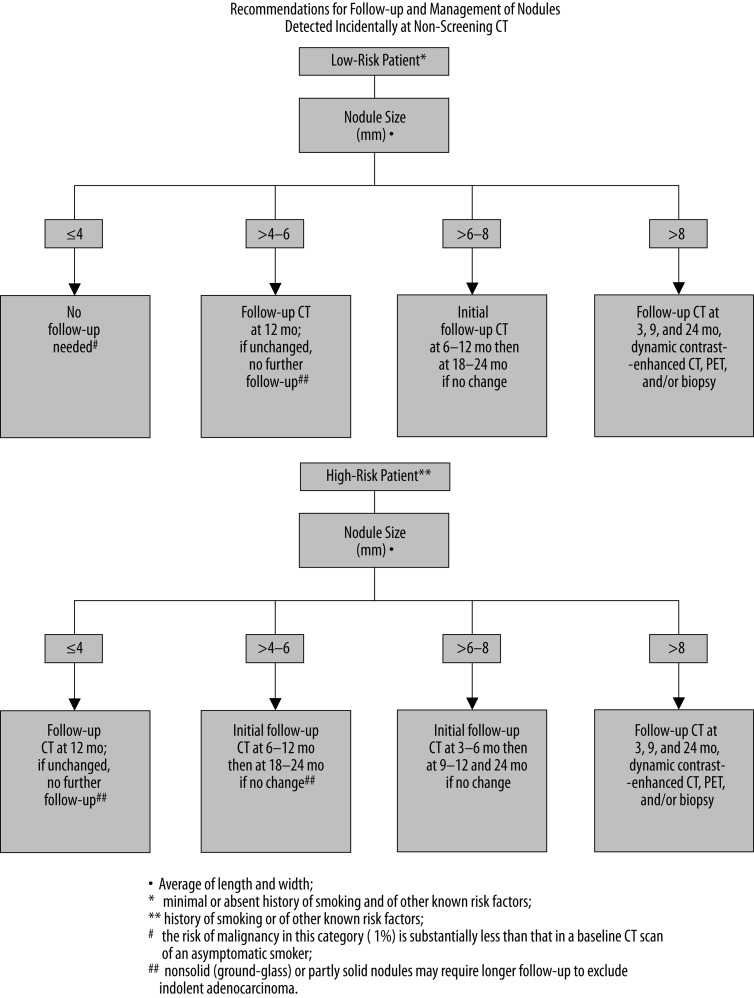

Lung cancer screening trials involve patients with high-risk factors. However, SPNs are commonly detected incidentally during CT examinations performed for purposes other than lung cancer screening. An evidence-based expert opinion recommendations created by the Fleischner Society apply to those incidentally found SPNs. The guidelines take into consideration patient’s lung cancer likelihood (high- or low-risk) based on risk factors (age, smoking history, exposure to asbestos, uranium, radon, or lung cancer history in first-degree relatives) and also imaging features of the nodule, with a size of a detected lesion being the most important factor. The summary of the Fleischner Society recommendations for a follow-up and management of nodules detected incidentally during non-screening CT are presented in Figure 26 [55]. When a follow-up of a detected nodule is the only indication for performing the CT examination, a low-dose, thin-section, unenhanced technique should be employed [55].

Figure 26.

The Fleischner Society recommendations for a follow-up and management of a solitary pulmonary nodule detected incidentally during a non-screening CT [55].

Above guidelines do not apply to [55]:

patients who have or are suspected to have any kind of malignancy, as their management should be based on relevant protocols or specific clinical situation,

young patients, less than 35 years of age; as the incidence of lung cancer in people less than 35 years old is very low (<1% of all cases), dependent on clinical situation, usually a single low-dose follow-up CT exam in 6–12 months should be sufficient,

patients with unexplained fever; a new opacity may indicate active infection; short-term imaging reexamination would be more appropriate.

The guidelines of the Fleischner Society for assessment of SPNs are generally well-known among radiologists. However, despite relatively high awareness of the guidelines existence, as shown by one study [56], continuing efforts are need to increase the implementation of these recommendations in routine clinical practice.

Additional set of guidelines, based on a systemic literature review and discussion with a large group of clinical experts was also created by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) [2]. This report involves recommendations for a management of SPNs with diameter of at least 8–10 mm, small nodules less than 8–10 mm in size and for detected multiple nodules. These guidelines take into consideration the presence of lung cancer risk factors, the usefulness of different imaging methods, the necessity to assess the potential benefits and risks of different management options (observation with imaging reassessment, biopsy, resection of the nodule) and also preferences of the patient.

The diagnostic approach to SPNs was also included in the American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria [57]. These evidence-based guidelines were developed by the panel of experts in diagnostic imaging, interventional radiology and radiation oncology. Their main goal was to evaluate the appropriateness of initial radiologic examination for patients presenting with a SPN. Different modalities such as: CT, with and without contrast, transthoracic needle biopsy, watchful waiting with follow-up CT, PET-CT whole body scan, etc were ranked and a scoring system from 1 to 9, indicating from the least to the most suitable imaging procedure, was proposed along with the assessment of a relative radiation level (RRL) for each imaging technique. Currently, however, the Fleischner Society Guidelines and ACCP Recommendations play a critical role in determining the management for a SPN, while the ACR Appropriateness Criteria play the adjunct role.

In the near future the evaluation of SPN will still remain a “hot topic”. Not only current methods of assessment are evolving and improving (for example more precise determination of nodule’s size and volume), but also new techniques are emerging. Studies have been looking for better, more accurate methods for assessment of SPNs, such as the usage of dual-energy CT [58] or more efficient clinical use of MRI [59,60]. Some authors put emphasis on future importance of patient’s genetic profiling which then can be combined with overall clinical presentation. Molecular imaging will also play increasingly important role. These methods are still experimental and will require ongoing research so that they can evolve into the most accurate and reliable techniques in assessment of a SPN.

Conclusions

Introduction and wide usage of helical and multi-detector CT has led to significant increase in the number of incidentally detected SPNs. Although most of these nodules are found to be benign, the appropriate pattern of management should be established based on the imaging features of a nodule combined with other above mentioned factors to exclude or diagnose malignancy. Some of the nodules can be called benign based on typical imaging findings, others may require additional follow-up or work-up with more invasive procedures like biopsy or even surgical resection.

By taking into consideration imaging features of a detected nodule, estimated probability of malignancy in a particular patient (age, risk factors, family history), risks and benefits of each procedure and also patient’s individual preferences in regard to the management, the best approach should be formulated.

Certainly, with multiple large studies on the way, more scientific data on the topic will become available. In the meantime, radiologists and clinicians should employ more widely and systematically the evidence-based guidelines and recommendations that have been established to date.

References:

- 1.Austin JH, Muller NL, Friedman PJ, et al. Glossary of terms for CT of the lungs: Recommendations of the nomenclature committee of the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 1996;200:327–31. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.2.8685321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gould MK, Fletcher J, Iannettoni MD, et al. American College of Chest Physician. Evaluation of patients with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer?: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132(Suppl.3):108S–30S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erasmus JJ, Connolly JE, McAdams HP, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: Part I. Morphologic evaluation for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. Radiographics. 2000;20:43–58. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.1.g00ja0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandman S, Ko JP. Pulmonary nodule detection, characterization, and management with multidetector computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging. 2011;26(2):90–105. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31821639a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholas E, Braff S, Klein JS. Evaluation of the solitary pulmonary nodule: A practical approach. Applied Radiology. http://www.appliedradiology.com/Issues/2011/12/Articles/AR_12-11_Klein-NIcholas/Evaluation-of-the-solitary-pulmonary-nodule--A-practical-approach.aspx (December 2011; vol.40, number 12) (accessed 29.04.2012) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zerhouni EA, Stitik FP, Siegelman SS, et al. CT of the pulmonary nodule: A cooperative study. Radiology. 1986;160:319–27. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.2.3726107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: Five-year prospective experience. Radiology. 2005;235:259–65. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351041662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354:99–105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Midthun DE, Swensen SJ, Jett JR, et al. Evaluation of nodules detected by screening for lung cancer with low dose spiral computed tomography. Lung Cancer. 2003;41(Suppl.2):S40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Naidich DP, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: suspiciousness of nodules according to size on baseline scans. Radiology. 2004;231(1):164–68. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2311030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Truong MT, Sabloff BS, Ko JP. Multidetector CT of solitary pulmonary nodules. Radiol Clin North Am. 2010;48(1):141–55. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurney JW. Determining the likelihood of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules with Bayesian analysis. Part I. Theory. Radiology. 1993;186:405–13. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.2.8421743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zwirewich CV, Vedal S, Miller RR, Muller NL. Solitary pulmonary nodule: High-resolution CT and radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1991;179:469–76. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.2.2014294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leef JL, III, Klein JS. The solitary pulmonary nodule. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:123–43. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(03)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegelman SS, Khouri NF, Scott WW, Jr, et al. Pulmonary hamartoma: CT findings. Radiology. 1986;160:313–17. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.2.3726106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muram TM, Aisen A. Fatty metastatic lesions in 2 patients with renal clear-cell carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27(6):869–70. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seo JB, Im JG, Goo JM, et al. Atypical pulmonary metastases: spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):403–17. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr17403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegelman SS, Khouri NF, Leo FP, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: CT assessment. Radiology. 1986;160:307–12. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.2.3726105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magid D, Siegelman SS, Eggleston JC, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid tumors: CT assessment. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:244–47. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198903000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodring JH, Fried AM, Chuang VP. Solitary cavities of the lung: diagnostic implications of cavity wall thickness. Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135:1269–71. doi: 10.2214/ajr.135.6.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodring JH, Fried AM. Significance of wall thickness in solitary cavities of the lung: a follow-up study. Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140:473–74. doi: 10.2214/ajr.140.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Mirtcheva R, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: Frequency and significance of part-solid and nonsolid nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1053–57. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.5.1781053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li F, Sone S, Abe H, et al. Malignant versus benign nodules at CT screening for lung cancer: comparison of thin-section CT findings. Radiology. 2004;233(3):793–98. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HY, Shim YM, Lee KS, et al. Persistent pulmonary nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: histopathologic comparisons. Radiology. 2007;245(1):267–75. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451061682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Hoop B, Gietema H, van de Vorst S, et al. Pulmonary ground-glass nodules: increase in mass as an early indicator of growth. Radiology. 2010;255(1):199–206. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yankelevitz DF, Henschke CI. Does 2-year stability imply that pulmonary nodules are benign? Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:325–28. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.2.9016198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz MA. A biomathematical approach to clinical tumor growth. Cancer. 1961;14:1272–94. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196111/12)14:6<1272::aid-cncr2820140618>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF. CT screening for lung cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:487–95. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lillington GA, Caskey CI. Evaluation and management of solitary multiple pulmonary nodules. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14:111–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aoki T, Nakata H, Watanabe H, et al. Evolution of peripheral lung adenocarcinomas: CT findings correlated with histology and tumor doubling time. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:763–68. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Yip R, et al. As the Writing Committee for the I-ELCAP Investigators: Lung Cancers Diagnosed at Annual CT Screening: Volume Doubling Times. Radiology. 2012;263(2):578–83. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12102489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchianò A, Calabrò E, Civelli E, et al. Pulmonary nodules: volume repeatability at multidetector CT lung cancer screening. Radiology. 2009;251(3):919–25. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2513081313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gietema HA, Wang Y, Xu D, et al. Pulmonary nodules detected at lung cancer screening: interobserver variability of semiautomated volume measurements. Radiology. 2006;241(1):251–57. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2411050860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White CS, Flukinger T, Jeudy J, et al. Use of a computer-aided detection system to detect missed lung cancer at chest radiography. Radiology. 2009;252(1):273–81. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522081319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubin GD, Paik DS, Sherbondy AJ, et al. Pulmonary nodules on multi-detector row CT scans: performance comparison of radiologists and computer-aided detection. Radiology. 2005 Jan;234(1):274–83. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn MI, Gleeson TG, Chan IH, et al. Perifissural nodules seen at CT screening for lung cancer. Radiology. 2010;254(3):949–56. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taniguchi Y, Nakamura H, Ito N, et al. Four cases of subpleural intrapulmonary lymph node. Kyobu Geka (Jpn J Thorac Surg) 1997;50:214–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taniguchi Y, Haruki T, Fujioka S, et al. Subpleural Intrapulmonary Lymph Node Metastasis from Colorectal Cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;15:250–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swensen SJ, Viggiano RW, Midthun DE, et al. Lung nodule enhancement at CT: multicenter study. Radiology. 2000;214:73–80. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yi CA, Lee KS, Kim EA, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: dynamic enhanced multi-detector row CT study and comparison with vascular endothelial growth factor and microvessel density. Radiology. 2004;233(1):191–99. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2331031535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong YJ, Lee KS, Jeong SY, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodule: Characterization with combined wash-in and washout features at dynamic multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2005;237:675–83. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah SK, McNitt-Gray MF, Rogers SR, et al. Computer aided characterization of the solitary pulmonary nodule using volumetric and contrast enhancement features. Acad Radiol. 2005;12(10):1310–19. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Amico TA, Wong TZ, Harpole DH, et al. Impact of computed tomography-positron emission tomography fusion in staging patients with thoracic malignancies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:160–63. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03693-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gould MK, Maclean CC, Kuschner WG, et al. Accuracy of positron emission tomography for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules and mass lesions: a metaanalysis. JAMA. 2001;285(7):914–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duhaylongsod FG, Lowe VJ, Patz EF, et al. Detection of primary and recurrent lung cancer by means of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:130–40. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(05)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higashi K, Ueda Y, Sakuma T, et al. Comparison of [18F]FDG PET and 201Tl SPECT in evaluation of pulmonary nodules. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Detterbeck FC, Falen S, Rivera MP, et al. Seeking a home for a PET, part 1. Defining the appropriate place for positron emission tomography imaging in the diagnosis of pulmonary nodules or masses. Chest. 2004;125:2294–99. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.6.2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klein JS, Zarka MA. Transthoracic needle biopsy: an overview. J Thorac Imaging. 1997;12(4):232–49. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klein JS, Zarka MA. Transthoracic needle biopsy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38:235–66. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aberle DR, Gamsu G, Henschke CI, et al. A consensus statement of the Society of Thoracic Radiology: screening for lung cancer with helical computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16(1):65–68. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman T, et al. Screening for lung cancer with CT: Mayo Clinic experience. Radiology. 2003;226(3):756–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2263020036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henschke CI, Naidich DP, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: initial findings on repeat screening. Cancer. 2001;92:153–59. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<153::aid-cncr1303>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: A statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237:395–400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eisenberg RL, Bankier AA, Boiselle PM. Compliance with Fleischner Society guidelines for management of small lung nodules: a survey of 834 radiologists. Radiology. 2010;255(1):218–24. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria Solitary Pulmonary Nodule. http://www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria/pdf/ExpertPanelonThoracicImaging/SolitaryPulmonaryNoduleDoc10.aspx; (accessed 29.04.2012) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chae EJ, Song JW, Seo JB, et al. Clinical utility of dual-energy CT in the evaluation of solitary pulmonary nodules: initial experience. Radiology. 2008;249(2):671–81. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492071956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fujimoto K, Abe T, Müller NL, et al. Small peripheral pulmonary carcinomas evaluated with dynamic MR imaging: correlation with tumor vascularity and prognosis. Radiology. 2003;227(3):786–93. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2273020459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schaefer JF, Vollmar J, Schick F, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging-perfusion differences in malignant and benign lesions. Radiology. 2004;232(2):544–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]