Abstract

Treatment for most patients with head and neck cancers includes ionizing radiation. A consequence of this treatment is irreversible damage to salivary glands (SGs), which is accompanied by a loss of fluid-secreting acinar-cells and a considerable decrease of saliva output. While there are currently no adequate conventional treatments for this condition, cell-based therapies are receiving increasing attention to regenerate SGs. In this study, we investigated whether bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) can differentiate into salivary epithelial cells and restore SG function in head and neck irradiated mice. BMDCs from male mice were transplanted into the tail-vein of 18 Gy-irradiated female mice. Salivary output was increased in mice that received BMDCs transplantation at week 8 and 24 post-irradiation. At 24 weeks after irradiation (IR), harvested SGs (submandibular and parotid glands) of BMDC-treated mice had greater weights than those of non-treated mice. Histological analysis shows that SGs of treated mice demonstrated an increased level of tissue regenerative activity such as blood vessel formation and cell proliferation, while apoptotic activity was increased in non-transplanted mice. The expression of stem cell markers (Sca-1 or c-kit) was detected in BMDC-treated SGs. Finally, we detected an increased ratio of acinar-cell area and approximately 9% of Y-chromosome-positive (donor-derived) salivary epithelial cells in BMDC-treated mice. We propose here that cell therapy using BMDCs can rescue the functional damage of irradiated SGs by direct differentiation of donor BMDCs into salivary epithelial cells.

Keywords: Cell therapy, Salivary gland, Head and neck irradiation, Bone marrow, Cell differentiation

1. Introduction

Ionizing radiation is a key component of therapy for most patients with head and neck cancers. Salivary glands, particularly the acinar cells, in the ionizing radiation field suffer severe damage. Since these cells are the principal site of fluid secretion in salivary glands, this leads to severe salivary gland hypofunction resulting in a broad range of problems such as xerostomia (dry mouth), dysphagia, severe dental caries, oro-pharyngeal infections, and mucositis (Vissink et al., 2003a, b). In many patients, all salivary parenchymal tissue is lost. These patients suffer considerable morbidity and a severe reduction in their quality of life. Unfortunately, there are no adequate treatments for patients with such irreversible gland damage. Current pharmacological approaches aim to increase the secretory capacity of the surviving acinar cells. However, this approach is not feasible if little or no acinar cells remain in the glands. Therefore, developing an adequate treatment by using alternative strategies, such as gene therapy, tissue engineering, or cell-based therapy, is required (Baum et al., 2002; Baum and Tran, 2006; Kagami et al., 2008).

For functional restoration of damaged salivary glands due to irradiation, two main regenerative approaches have been tested to date. The first approach is to develop an artificial salivary gland using tissue engineering principles (Tran et al., 2005; Joraku et al., 2005; Tran et al., 2006; Aframian et al., 2007; Yang and Young, 2008; Aframian and Palmon, 2008; Pradhan et al., 2010). We recently reported that it was feasible to culture salivary epithelial cells for their eventual use in a prototype artificial salivary gland (Tran et al., 2006). However, this strategy can generate only one portion of the salivary parenchymal tissue (the ductal cells), and it has been difficult for our group to regenerate fully functional salivary tissue (both ductal and acinar cells). A second approach has been to apply stem cell-based therapy to damaged salivary gland tissue. Currently, stem cells from two different organs have been investigated: (a) from the salivary gland (Sugito et al., 2004; Lombaert et al., 2008a; Tatsuishi et al., 2009; Feng et al., 2009) or (b) from the bone marrow (Lombaert et al., 2006; Tran et al., 2007; Lombaert et al., 2008b; Coppes et al., 2009). Using cells from salivary glands, Sugito et al. (2004) demonstrated that cultured rat salivary epithelial cells could be transplanted into atrophic salivary glands. These cells remained in the damaged salivary tissue for 4 weeks. Moreover, Lombaert et al. (2008a) developed an in vitro culture system to enrich, characterize, and harvest primitive salivary gland stem cells. These cultured cells could rescue the gland functions after transplantation. However, this strategy may be difficult for clinical use if an insufficient number of stem cells are obtained from patients’ gland biopsies. Also, to establish an adequate culture condition for each patient may be challenging. Many patients with head and neck cancers are old. Gland tissues tend to be atrophic in older patients. Therefore, to expand these patients’ salivary stem cells in vitro (after surgical removal) may be difficult, as cell viability has already decreased. Another source of stem cells that have been suggested to potentially differentiate or repair non-hematopoietic organs are bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) (Lagasse et al., 2000; Orlic et al., 2001; Nishida et al., 2004; Couzin, 2006). Specifically for the salivary glands, Lombaert et al. (2006) reported that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) treatment induced mobilization of a large number of BMDCs to mouse salivary glands that had received irradiation to their neck area. Their results suggest that BMDCs could be mobilized from the BM and homed to injured salivary glands to participate in repair processes that improved gland’s function and morphology. From our previous study, we reported that BMDCs from healthy male donors can differentiate into buccal (oral) epithelial cells of female transplant recipients (Tran et al., 2003). Taking these studies together lead us to hypothesize that transplanted BMDCs (intravenously) would mobilize to irradiation-damaged salivary glands, differentiate into salivary epithelial cells and improve the gland’s function. This phenomenon would have implications for the use of BMDCs in the treatment of salivary dysfunctions for which no suitable conventional treatments are currently available. BMDCs are readily accessible and provide an easy and minimally invasive procedure to harvest from patients with head and neck cancers, before their chemo-irradiation therapy.

The aim of this study was to assess the regenerative capacity of BMDCs for salivary gland regeneration by their direct transplantations through intravenous injections. This study is a pre-requisite step for future clinical trials aiming at developing cell-based therapy for salivary glands. We believe that using enriched BMDCs, without an in vitro culture system, is a simple and direct approach for transplantation; and that this strategy should be investigated as a priority to regenerate salivary glands.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Female C3H mice of 8 weeks old (Charles River, Montreal, QC, Canada) were used as recipient mice in a gender-mismatched bone marrow transplantation strategy. Donor mice were age-matched male C3H mice. All mice were kept under clean conventional conditions at the McGill University animal resource center. We received an approval for the animal use from the University Animal Care Committee in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

2.2. Irradiation

Mice were treated at 8 weeks of age and salivary gland damage was elicited by local head and neck radiation exposure of 18 Gy using a gamma cell cesium-137 unit. We selected this radiation dosage based on results from our pilot study testing 12, 15, 18, 22, and 25 Gy, which was aimed at inducing 30–50% reduction of saliva flow rate. A dose rate of 12 Gy did not achieve our aim, while 22 and 25 Gy were too severe for the health of the mice. 15 Gy decreased 30% of saliva flow, and 18 Gy 50%, at 8 weeks post-irradiation. We report here results from mice irradiated with 18 Gy. A brief mention of results from 15 Gy is included in the discussion section to allow a comparison with studies that used 15 Gy. For irradiation, the mice were anesthetized with 1 μl/g body weight of a 60 mg/ml ketamine and 8 mg/ml xylazine (Phoenix Scientific) solution given intra-peritoneally (i.p.), and placed in a 3 mm-thick Perspex box, which was aligned in the radiation unit. The dose rate to the local head and neck was calculated monthly according to the decay formula provided by the company. The rest of the body was shielded with 3 cm of lead to reduce the beam strength to 3% in this area. Female mice were divided into 3 different groups (5 mice per group) and were followed for 24 weeks post irradiation with either: (a) irradiation plus injections of bone marrow cells (18 Gy + BMDCs), (b) irradiation and no-cell transplant groups (18 Gy), (c) no-irradiation and no cell-transplant group.

2.3. Bone marrow derived-cells (BMDCs) transplantation

8-week old male C3H mice were the donors. Bone marrow was harvested as follows: (a) dissecting connective tissue to obtain clean femur and tibia bones, (b) cutting off each end of the femur and tibia bones to expose their marrow, (c) inserting a 25-gauge needle in the marrow opening, (d) flushing out the marrow using a syringe filled with filtered Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 2% antibiotic–antimycotic reagent (Sigma), and (e) resuspending the bone marrow in DMEM and filtering it through a 40-μm filter to remove any particulates. The mixture was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended with medium kept on ice before transplantation. The injection of 1 × 107 BMDCs was done via the tail vein immediately after irradiation, and the transplantations were repeated two times per week during 6 consecutive weeks. We selected this frequency of injections and quantity of cells based on the effectiveness of this regimen from our collaborators’ studies on diabetes as well as from our own study in Sjögren’s syndrome (Kodama et al., 2003; Tran et al., 2007). We have selected to deliver BMDCs intravenously based from our previous finding that BMDCs from healthy male donors differentiated into oral epithelial cells of female transplant recipients (Tran et al., 2003), and more recently into salivary epithelial cells (unpublished data).

2.4. Salivary flow rate

Secretory function of the salivary glands (salivary flow rate) was obtained by i.p. injection of 1 μl/g body weight of a 60 mg/ml ketamine and 8 mg/ml xylazine mixture. Whole saliva was collected after stimulation of secretion using 0.5 mg Pilocarpine (Sigma)/kg body weight administered subcutaneously. Saliva was obtained from the oral cavity by micropipette, placed into pre-weighed 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes. Saliva was collected for a 10-min period and its volume determined gravimetrically. Salivary flow rate (SFR) was determined at baseline and at week 8, 16, and 24 post-irradiation.

2.5. Measurement of gland weight

At 24 weeks, the mice were sacrificed and their submandibular glands harvested. Before fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin, the weights of the harvested gland tissues were measured.

2.6. Morphological and histological examination

2.6.1. Apoptosis

The ApopTag® In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Chemicon, MA, USA) was used to evaluate apoptotic cells by detecting DNA cleavage and chromatin condensation associated with apoptosis using a mixed molecular biological–histochemical system. After deparaffinization and rehydration, slides were pre-treated with protein digestion enzyme (proteinase) for 15 min at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked for 10 min by H2O2 in methanol. TdT enzyme was incubated with the slides for 1 h, and then, anti-digoxigenin conjugate for 30 min at room temperature. Peroxidase substrate was applied to develop the reaction color and the slides were counterstained in 0.5% (w/v) methyl green for 10 min. The nuclei of apoptotic cells were stained dark brown. Two examiners independently counted the absolute number of apoptotic cells each in five randomly chosen fields per section at the magnification of ×400. The means and standard deviations of each mouse groups were calculated.

2.6.2. Blood vessel staining

Five-micrometer thickness tissue sections were stained by immuno-histochemistry using the Blood Vessel Staining Kit (Chemicon, MA, USA). After deparaffinizing and rehydration, tissue sections were treated three times with a citrate buffer solution (9 ml of 0.1 M citric acid and 41 ml of 0.1 M sodium citrate plus 450 ml distilled water) in a 600 W microwave and then allowed to cool to room temperature for 30 min before blocking overnight at 4 °C. Rabbit anti-human vWF was used (1:100) for 2 h at room temperature. After that, we followed the manufacturer’s instructions. The percentage of surface area occupied by blood vessels was assessed by light microscopy under ×400 magnification using 3 sections for each slide. At least 10 fields per section were accounted using NIH J Image software (NIH, Bethesda, USA).

2.6.3. Cell proliferation staining

After deparaffinization and rehydration, tissue sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min. PCNA staining was performed with the Zymed PCNA staining kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Before antibody labeling, the slides were treated three times with a citrate buffer solution (mentioned previously) in a 600 W microwave for 5 min. Thereafter, slides were processed with routine indirect immunoperoxidase techniques. Two examiners independently counted the absolute number of PCNA positive cells in a blinded manner in five randomly chosen sections (n = 5 glands/group) at the magnification of ×400.

2.6.4. PAS staining

Tissue sections were analyzed using Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) method (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The percentage of surface area occupied by acinar cells was assessed by light microscopy under ×400 magnification; for 3 tissue sections per slide. At least 10 random fields per section were analyzed by NIH J Image software (NIH).

2.7. Composition of saliva

2.7.1. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) concentration

Concentration of EGF in saliva was measured by ELISA method (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at week 24 post irradiation. This assay employed a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoas-say technique. The intensity of the color measured is in proportional to the amount of EGF. The sample values were compared to the EGF standard curve.

2.7.2. Total proteins concentration

Total proteins from saliva was assayed by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) kit (Thermo Scientific, Pierce, IL, USA) at week 24 post irradiation. Three microliters from each saliva sample was used for the assay. OD values were measured at 562 nm and the results were expressed in μg/ml, assuming that 1 g weight difference of saliva is equal to 1 ml.

2.8. Immuno-histochemical staining

Frozen salivary tissue sections (5 μm thickness) from mice were fixed in cold methanol for 10 min, followed by three washing steps in PBS for 5 min each. Endogenous peroxidase and biotin activities were blocked with hydrogen peroxide 3% and the Universal Blocking solution (BioGenex, San Roman, CA, USA), respectively. We used the following primary antibodies to test the expression of stem/progenitor cells; Sca-1 and c-Kit (Cat. AF1226 and Cat. MAB1356, R&D Systems). We used isotype control antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) that are reactive against the respective proteins from mice and other species. Donkey anti-goat-FITC and anti-rat-FITC secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). All primary antibodies used were diluted 1:100 in PBS containing 5% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). The slides were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, and in the dark with the secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Then 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added for 3–5 min. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue slides, we used the same steps as described above, in addition to a boiling step (15 min) using an EDTA solution (pH 8.0, Zymed Labs) for heat-induced epitope retrieval.

2.9. Immunostaining and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Serial frozen tissue sections were fixed in a 2% paraformaldehyde fixative for 10 min. Immunostaining was performed by primary antibody that was detected by the Sternberger peroxidase antiperoxidase (PAP) method followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (FITC)-tyramide signal amplification (TSA System, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The primary antibody used was directed against the Na+–K+–Cl−co-transporter type 1 (NKCC1, a marker for salivary acinar cell; graciously donated by Dr. R. James Turner, NIH, USA) and Cytokeratins 8, 13 and 18 (salivary epithelial cell markers; Biogenex, USA) to detect salivary epithelial cells. A digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe was then added to recognize a repeat sequence (pY353B) on the mouse Y-chromosome. Endogenous peroxidase in the tissue was blocked using a commercially available reagent (DAKO, CA, USA). The riboprobe was then detected using a HRP conjugated antibody to digoxigenin (Roche, Indianapolis, USA). The peroxidase was then visualized by using an Alexa Fluor 594 fluorochrome-tyramide reagent (TSA System, Invitrogen). All sections were stained with DAPI to label all nuclei and then mounted with Tris (hydroxymethyl)–aminomethane, [pH 7.4]) buffer. Finally the slides were visualized using a Leica DM6000 fluorescent microscope equipped with Volocity software. The percentage of Y-chromosome positive cells was calculated by taking the number of Y-chromosome cytokeratin-positive cells divided by the number of cytokeratin-positive cells (i.e. epithelial cells that are Y-chromosome positive in a female mouse salivary gland). This count was done from 3 tissue sections per gland under ×400 magnification by two examiners independently. At least 5 random fields were chosen per tissue section.

2.10. Statistical analysis

To determine statistical significance (p < 0.05), Linear Mixed Models and ANOVA analysis (Tukey’s test) were used. Mice between and within the groups were compared in different time points by SPSS version 17 (IBM, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Saliva production and gland weight

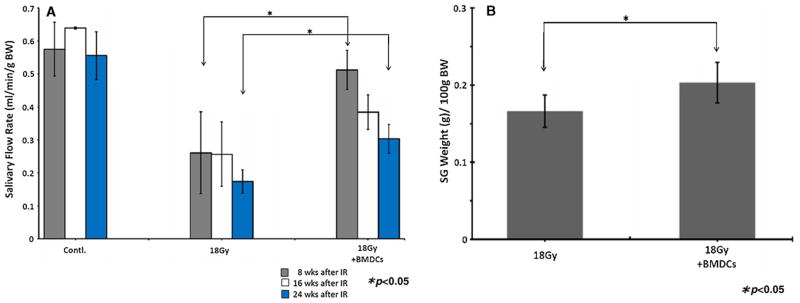

Saliva output (salivary flow rate; SFR) were assessed at week 8, 16 and 24 post-irradiation (post-IR) to determine the effect of BMDCs transplantation on the functional restoration of damaged glands. Overall SFR was greater in BMDC-transplanted mice at week 8 and 24 post-IR when compared to non-transplanted mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 1A). Remarkably, SFR of irradiated BMDC-transplanted mice at week 8 post-IR were increased to levels comparable to those of normal non-irradiated control mice, and were significantly higher than those of non-transplanted mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 1A). However, SFR of BMDC-treated mice at 16 weeks after irradiation decreased to approximately 70–80% of SFR measured at 8 weeks. After the final SFR measurements (at week 24), all animals were sacrificed and their salivary glands were weighed. Submandibular glands of BMDC-treated mice had greater weights than those of non-treated mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) Salivary flow rate (SFR) at 8, 16 and 24 weeks post-irradiation (18 Gy to the head and neck area). SFR were higher in BMDC-transplanted mice when compared to non-transplanted ones at 8 and 24 weeks (*p < 0.05). (B) Weight of salivary glands harvested at 24 weeks after irradiation. The glands of BMDC-treated mice had greater weights than those of irradiated mice (*p < 0.05). Results are reported as mean ± SD; n = 5 mice per group.

3.2. Tissue restoration in glands at 24 weeks post-irradiation

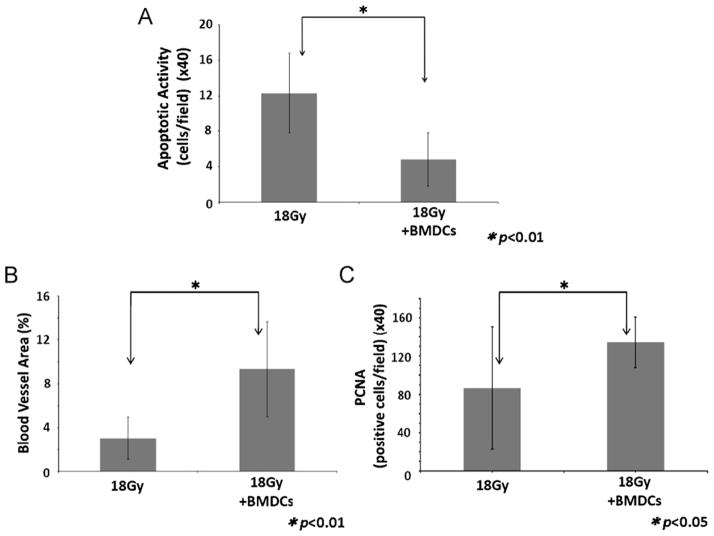

Firstly, apoptotic activity was assessed to determine the effect of BMDCs transplantation for the prevention of apoptosis in damaged salivary epithelial tissues. At 24 weeks, BMDC-treated mice showed a significantly lower apoptotic activity when compared to non-transplanted mice (p < 0.01; Fig. 2A). Secondly, vascularization in damaged tissues was assessed by measuring the percentage of surface area occupied by blood vessels in each gland. This % of blood vessels in BMDCs-treated mice was ~2.5-fold larger than that from non-transplanted mice (p < 0.01; Fig. 2B). Thirdly, PCNA-positive cells were counted to assess the proliferative activity of salivary epithelial cells in irradiation-damaged tissues. At 24 weeks post-IR, the number of proliferating cells significantly increased in BMDC-treated mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 2C). From these findings we speculate that transplanted BMDCs (cell therapy) possess a paracrine and a vasculogenesis effect that inhibited the apoptosis and increased the proliferative activity of acinar cells.

Fig. 2.

(A) Cell apoptotic activity evaluated at 24 weeks after 18 Gy of irradiation. There is a statistically significant decrease (*p < 0.01) in the number of apoptotic cells in the BMDC-treated mice after irradiation. (B) Area of intact blood vessels (reported as a percentage of the salivary tissue surface examined) evaluated at 24 weeks after 18 Gy irradiation. There is a statistically significant increase (*p < 0.01) in the percentage of blood vessels area in mice which received BMDCs transplant. (C) Cell mitotic activity (PCNA stained) evaluated at 24 weeks after irradiation. There is a statistically significant increase (*p < 0.05) in the number of dividing cells in mice transplanted with BMDCs. Results are reported as mean ± SD; n = 5 mice per group.

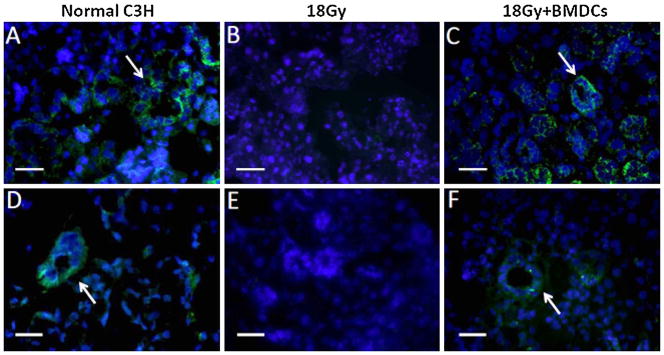

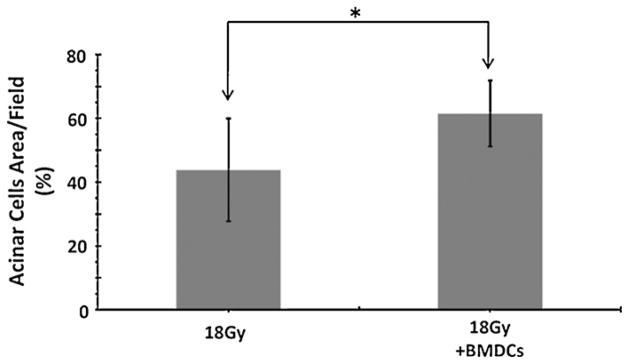

We also asked if this cell therapy increased the proliferation of putative salivary stem cells. We analyzed the expression of stem cell markers by fluorescence immunocytochemistry to detect the stem/progenitor cells which contribute to the regeneration of gland tissues. The expression of c-Kit and Sca-1 was found mainly in the ductal portion of non-irradiated control and BMDC-transplanted mice, while absent in glands of irradiated but non-transplanted mice (Fig. 3). Therefore we concluded that BMDCs allowed the maintenance of putative salivary stem cells, but did not increase their proliferative activity (as much as they did for acinar cells). Consistent with these findings, the regeneration of acinar cells (measured as a percentage of acinar cells per surface area) was higher in BMDC-treated mice when compared to non-transplanted mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Stem cell markers in mouse salivary tissue at 24 week post-irradiation. (A) C-Kit (CD117; stained in green) is expressed in striated and excretory duct cells (shown by arrow) of non-irradiated submandibular glands. (B) C-Kit is absent in 18 Gy-irradiated submandibular glands, (C) while it is highly expressed by all ductal cells in 18 Gy-irradiated mouse transplanted with BMDCs. (D) Sca-1 (stained in green) is detected in some striated duct cells (arrow) of non-irradiated C3H mouse submandibular gland. (E) Sca-1 is absent in 18 Gy-irradiated glands, (F) but is highly expressed by some ductal cells in 18 Gy-irradiated mouse treated with BMDCs. The Sca-1 signal in all tissue sections is weaker than that of the C-Kit signal. These stem cell markers are labeled by FITC (green); nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 34 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Fig. 4.

Area of acinar cells (reported as a percentage of the salivary tissue surface examined) at 24 weeks after 18 Gy irradiation. The % area of acinar cells is higher in BMDC-treated mice (*p < 0.05). Results are reported as mean ± SD; n = 5 mice per group.

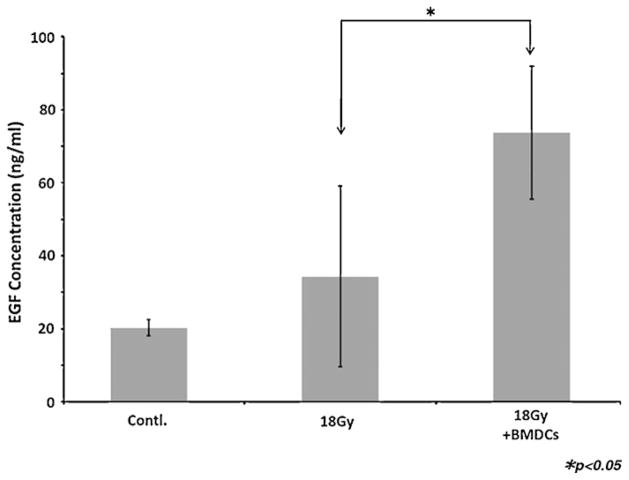

3.3. Analysis of saliva composition

The concentration of EGF in saliva secreted from BMDC-treated mice was markedly elevated when compared to that of non-transplanted mice (p < 0.05; Fig. 5). Total proteins concentration between BMDCs and non-BMDCs transplanted mice were not statistically significantly different (p = 0.06; Supplemental Fig. 2) although there was a higher trend toward the non-transplanted mice.

Fig. 5.

Concentration of EGF in saliva. The saliva secreted from BMDC-treated mice was increased in EGF when compared to non-transplanted mice (p < 0.05). Results are reported as mean ± SD; n = 5 mice per group.

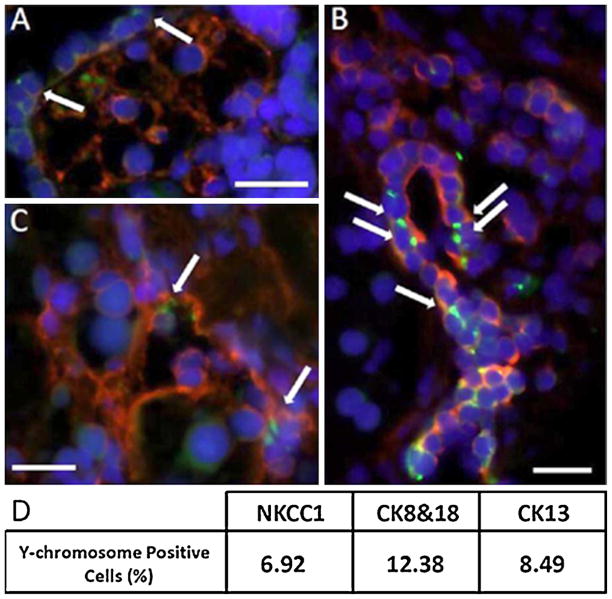

3.4. Detection of Y-chromosome positive cells in female mouse salivary glands after BMDCs transplantation

We combined fluorescence in situ hybridization with immuno-histochemical staining to allow for the simultaneous detection of both the Y-chromosome and specific markers for salivary epithelial cells. Approximately 9% of salivary epithelial cells in BMDC-transplanted mice were Y-chromosome positive (i.e. derived from donor BMDCs), but none in non-transplanted or normal control mice. These positive cells were observed in salivary epithelial cells which expressed NKCC1 (acinar cell marker; Fig. 6A), cytokeratins 8 and 18 (salivary epithelial cell marker; Fig. 6B) and cytokeratin13 (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Double immunostaining in 18 Gy-irradiated salivary glands of female mice transplanted with male-BMDCs. (A) The Y-chromosome signal is a green dot (shown by the arrow) and the co-transporter for Na–K–2Cl type 1 is a red signal that surrounds the cell membrane (NKCC1 is a marker of salivary acinar cells). Nuclei are stained in blue with DAPI. (B) We observed several Y chromosome cells (arrows; green dot) that are cytokeratins 8 and 18 positive (shown by the red signal), or (C) cytokeratin 13 positive (shown by the red signal). Cytokeratins 8, 18 and 13 are used here as markers of salivary epithelial cells. The scale bar represents 34 μm in all three panels. (D) Percentage of Y-chromosome-positive salivary epithelial cells in BMDC-transplanted mice. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that a cell-therapy approach, such as transplantation of BMDCs via intravenous injections, can regenerate radiation-damaged tissue and rescue salivary gland functions. Our successful treatment outcomes were: (1) restoration of saliva production, (2) promotion of tissue regenerative activity, (3) direct differentiation of donor BMDCs into salivary epithelial cells.

Regarding the restoration of saliva production, we found higher SFR in BMDC-treated mice when compared to irradiated control mice at week 8 and 24 post-irradiation (p < 0.05; Fig. 1A). At week 8 post-IR, SFR of BMDC-treated mice were ~2-folds higher than that of irradiated mice, and at a comparable level with that of non-irradiated (normal) C3H mice. However, this therapeutic effect on SFR was gradually reduced at week 16 and 24 post-IR. We believe this finding can be explained, first, due to a further loss of acinar cells during the late-effect phase post-IR, and second, that the therapeutic effect was at its peak during the six bi-weekly injections of BMDCs post-IR. First, radiation to salivary gland causes a loss of acinar cells during the late-effect phase post-IR (Urek et al., 2005; Zeilstra et al., 2000). Prominent acinar cells loss was reported 90 days (13 weeks) after irradiation in mouse submandibular glands. Urek et al. (2005) speculated that radiation-induced sublethal-DNA damage became apparent during the late-effect phase post-IR due to a slow cell turnover rate. Furthermore, Feng et al. (2009) reported that human salivary glands continued to show a severe reduction in the number of acinar cells even 15 years after radiotherapy. Consistent with these studies, we observed that our irradiated mice continued to have a reduction in saliva secretion from 8 to 24 weeks post-IR (Supplemental Fig. 1). Therefore, it is not unlikely that the gradual reduction in SFR observed in BMDC-treated mice was partially due to the consequences of this late-effect phase on acinar cells. However SFR of BMDC-treated mice were still higher than that of non-transplanted mice. Moreover, the area of acinar cells in submandibular glands of BMDC-treated mice was significantly larger than that of non-transplanted mice at 24 weeks post-IR. Therefore, BMDC-transplantations did partially prevent acinar cell loss during the late post-IR phase and these findings suggest BMDCs did provide a therapeutic effect on salivary glands. Second, while the exact mechanisms by which BMDCs improve salivary functions remain controversial, we speculate that a combination of mechanisms such as transdifferentiation, vasculogenesis, and a paracrine effect of BMDCs occur in salivary glands during the transplantation period of 6 weeks. Beyond that time, with no further new BMDC-transplanted, these mechanisms decreased and the initial therapeutic observed gradually diminished. To stabilize the improvement in salivary flow for long-term therapy, we will investigate in future studies optimal BMDCs dosage, efficient time-interval, and methods to deliver BMDCs locally to the salivary glands (as compared to intravenously in this study).

With regard to the promotion of tissue regenerative activity, our findings are comparable with those reported by Lombaert et al. (2006). They reported that the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) treatment induced mobilization of a large number of BMDCs from mouse bone marrow to salivary glands that had received irradiation to their neck area. Although no transdifferentiation of BMDCs to salivary epithelial cells were observed in their study, they speculated that both hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells mobilized from bone marrow by G-CSF could stimulate the recovery of the salivary gland cells. To date, several mechanisms by which BMDCs improve organ functions have been reported. These include cell fusion, cell transdifferentiation, induction of vasculogenesis, or paracrine effects (Burt et al., 2008). The exact mechanisms remain unclear. However, Lombaert’s and our findings support the hypothesis that BMDCs could, at least, induce vasculogenesis and paracrine effect in salivary gland. We found that the inhibition of apoptosis and the increase of tissue regenerative activity, such as blood vessels and cell proliferation, occurred mainly in the acinar cell area of BMDC-transplanted mice. Furthermore, the expression of salivary gland stem cell markers was observed in the damaged tissues of BMDC-treated mice. More recently, Tatsuishi et al. (2009) demonstrated that the salivary gland stem/progenitor cells could survive and remain dormant after irradiation, but their survival rate depended on the radiation dosage and cell age. We used young (8-week old) C3H mice and a radiation dosage that caused approximately 50% decline in saliva production after 8 weeks of irradiation. The presence of c-Kit and Sca-1 positive cells in treated-mice suggest that the transplanted BMDCs may provide a local paracrine effect for re-activation of dormant stem cells which survived the irradiation process. In future studies we would need to verify our assumption, first, by assessing the percentage of c-kit (or sca-1) positive cells in normal glands and after cell therapy using FACS. Second, since BMDCs also contains c-kit and sca-1 positive cells, we would need to show the origin of these putative salivary stem cells.

A main difference from our results was the detection of 9% Y-chromosome positive cells in salivary epithelial cells of BMDC-treated mice, as compared to none in the Lombaert’s studies (Lombaert et al., 2006). Our results suggest that transplanted exogenous BMDCs can differentiate into salivary cells, when compared to endogenous BMDCs mobilized from the host bone marrow using G-CSF. In general, somatic stem/progenitor cells might possess tissue-specific characteristics that may inhibit their transdifferentiation in the body. However, once isolated into single cells, they become more plastic (Widera et al., 2009; Yalvac et al., 2010). In this study, we harvested the bone marrow from the male donor mice, and isolated BMDCs by 40-μm cell strainer. Then, these BMDCs were transplanted as a model of cell therapy. Other experimental variables that may explain our observations that BMDCs differentiated in salivary epithelial cells were: (a) multiple injections of BMDCs (12 injections during 6 weeks), and (b) injection of BMDCs within 24 h of irradiation damage to the salivary glands.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrated the capacity of BMDCs for salivary gland regeneration by their direct transplantation through intravenous injection. Although the mechanisms of transplanted BMDCs that lead the regeneration of damaged tissue remain unclear, we observed the phenomenon of differentiation of BMDCs to salivary epithelial cells. We believe that the restoration of function and morphology arose from a combination of several factors such as vasculogenesis, paracrine effect, and cell transdifferentiation by hematopoietic and/or mesenchymal cells that derived from bone marrow. For future clinical applications, additional investigations are needed to understand the mechanisms of transplanted BMDCs that lead to radiation-damaged tissue regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Christina K. Haston (McGill University) for her guidance in the fabrication of the lead shield; Dr. R. James Turner (NIDCR/NIH) for donating the NaKCl-cotransporter antibody. We also wish to thank the staff at the McGill University animal facility, the Centre for Bone and Periodontal Research, and the Department of Engineering for technical assistance. This study was supported in part by research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Canada Research Chair.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2010.09.023.

References

- Aframian DJ, Amit D, David R, Shai E, Deutsch D, Honigman A, et al. Reengineering salivary gland cells to enhance protein secretion for use in developing artificial salivary gland device. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:995–1001. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aframian DJ, Palmon A. Current status of the development of an artificial salivary gland. Tissue Eng Part B: Rev. 2008;14:187–98. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum BJ, Kok M, Tran SD, Yamano S. The impact of gene therapy on dentistry: a revisiting after six years. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:35–44. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum BJ, Tran SD. Synergy between genetic and tissue engineering—creating an artificial salivary gland. Periodontol 2000. 2006;41:218–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RK, Loh Y, Pearce W, Beohar N, Barr WG, Craig R, et al. Clinical applications of blood-derived and marrow-derived stem cells for nonmalignant disease. JAMA. 2008;299:925–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppes RP, van der Goot A, Lombaert IM. Stem cell therapy to reduce radiation-induced normal tissue damage. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19:112–21. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzin J. Clinical trials. A shot of bone marrow can help the heart. Science. 2006;313:1715–6. doi: 10.1126/science.313.5794.1715a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, van der Zwaag M, Stokman MA, van Os R, Coppes RP. Isolation and characterization of human salivary gland cells for stem cell transplantation to reduce radiation-induced hyposalivation. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:466–71. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joraku A, Sullivan CA, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Tissue engineering of functional salivary gland tissue. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:244–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000154726.77915.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagami H, Wang S, Hai B. Restoring the function of salivary glands. Oral Dis. 2008;14:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S, Kuhtreiber W, Fujimura S, Dale EA, Faustman DL. Islet regeneration during the reversal of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Science. 2003;302:1223–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1088949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagasse E, Connors H, Al-Dhalimy M, Reitsma M, Dohse M, Osborne L, et al. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:1229–34. doi: 10.1038/81326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombaert IM, Wierenga PK, Kok T, Kampinga HH, deHaan G, Coppes RP. Mobilization of bone marrow stem cells by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor ameliorates radiation-induced damage to salivary glands. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1804–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombaert IM, Brunsting JF, Wierenga PK, Faber H, Stokman MA, Kok T, et al. Rescue of salivary gland function after stem cell transplantation in irradiated glands. PLoS One. 2008a;3:e2063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombaert IM, Brunsting JF, Wierenga PK, Kampinga HH, de Haan G, Coppes RP. Cytokine treatment improves parenchymal and vascular damage of salivary glands after irradiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2008b;14:7741–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, Fujimoto S, Toiyama K, Sato H, Hamaoka K. Effect of hematopoietic cytokines on renal function in cisplatin-induced ARF in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–5. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan S, Liu C, Zhang C, Jia X, Farach-Carson MC, Witt RL. Lumen formation in three-dimensional cultures of salivary acinar cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:191–5. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugito T, Kagami H, Hata K, Nishiguchi H, Ueda M. Transplantation of cultured salivary gland cells into an atrophic salivary gland. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:691–9. doi: 10.3727/000000004783983567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuishi Y, Hirota M, Kishi T, Adachi M, Fukui T, Mitsudo K, et al. Human salivary gland stem/progenitor cells remain dormant even after irradiation. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:361–6. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran SD, Pillemer SR, Dutra A, Barrett AJ, Brownstein MJ, Key S, et al. Differentiation of human bone marrow-derived cells into buccal epithelial cells in vivo: a molecular analytical study. Lancet. 2003;361:1084–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12894-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran SD, Wang J, Bandyopadhyay BC, Redman RS, Dutra A, Pak E, et al. Primary culture of polarized human salivary epithelial cells for use in developing an artificial salivary gland. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:172–81. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran SD, Sugito T, Dipasquale G, Cotrim AP, Bandyopadhyay BC, Riddle K, et al. Re-engineering primary epithelial cells from rhesus monkey parotid glands for use in developing an artificial salivary gland. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2939–48. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran SD, Kodama S, Lodde BM, Szalayova I, Key S, Khalili S, et al. Reversal of Sjogren’s-like syndrome in non-obese diabetic mice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:812–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.064030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urek MM, Bralic M, Tomac J, Borcic J, Uhac I, Glazar I, et al. Early and late effect of X-irradiation on submandibular gland: a morphological study in mice. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:339–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissink A, Burlage FR, Spijkervet FK, Jansma J, Coppes RP. Prevention and treatment of the consequences of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003a;14:213–25. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissink A, Jansma J, Spijkervet FK, Burlage FR, Coopes RP. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003b;14:199–212. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera D, Zander C, Heidbreder M, Kasperek Y, Noll T, Seitz O, et al. Adult palatum as a novel source of neural crest-related stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1899–910. doi: 10.1002/stem.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalvac ME, Ramazanoglu M, Rizvanov AA, Sahin F, Bayrak OF, Salli U, et al. Isolation and characterization of stem cells derived from human third molar tooth germs of young adults: implications in neo-vascularization, osteo-, adipo-, and neurogenesis. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10:105–13. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TL, Young TH. The enhancement of submandibular gland branch formation on chitosan membranes. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2501–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilstra LJ, Vissink A, Konings AT, Coppes RP. Radiation induced cell loss in rat submadibular gland and its relation to gland function. Int J Radiat Biol. 2000;76:419–29. doi: 10.1080/095530000138763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.