Abstract

Purpose

Previous research showed that pretreatment uptake of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), as assessed by the maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax) and the variability of uptake (FDGhetero), predicted for posttreatment response in cervical cancer. In this pilot study, we evaluated the changes in SUVmax and FDGhetero during concurrent chemoradiation for cervical cancer and their association with posttreatment response.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-five patients with stage Ib1-IVa cervical cancer were enrolled. SUVmax, FDGhetero and metabolic tumor volume (MTV) were recorded from FDG-PET/CT scans performed pretreatment and during weeks 2 and 4 of treatment and were evaluated for changes and association with response assessed on 3-month posttreatment FDG-PET/CT.

Results

For all patients, the average pretreatment SUVmax was 17.8, MTV was 55.4 cm3, FDGhetero was −1.33. A similar decline in SUVmax was seen at week 2 compared to baseline and week 4 compared to week 2 (34%). The areas of highest FDG uptake in the tumor remained relatively consistent on serial scans. Mean FDGhetero decreased during treatment. For all patients, MTV decreased more from week 2 to week 4 than from pretreatment to week 2. By week 4, the average SUVmax had decreased by 57% and the MTV had decreased by 30%. Five patients showed persistent or new disease on 3-month posttreatment PET. These poor responders showed a higher average SUVmax, larger MTV, and greater heterogeneity at all 3 times. Week 4 SUVmax (p=0.037), week 4 FDGhetero (p=0.005), pretreatment MTV (p=0.008) and pretreatment FDGhetero (p=0.008) were all significantly associated with posttreatment PET response.

Conclusions

SUVmax shows a consistent rate of decline during treatment and declines at a faster rate than MTV regresses. Based on this pilot study, pretreatment and week 4 of treatment represent the best time points for prediction of response.

Keywords: cervical cancer, FDG-PET, during treatment response, SUVmax, heterogeneity

Introduction

Approximately 20–40% of patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with definitive chemoradiation will have persistent or recurrent disease following treatment (1, 2). Being able to identify those patients at high risk for a poor response to conventional therapy before or during treatment could lead to improved outcomes through modification of the treatment plan or use of adjuvant therapy.

Previous studies identified three different positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) based prognostic factors for intact cervical cancer being treated definitively with concurrent chemoradiation. Specifically, high FDG uptake in the primary cervical tumor, measured as the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) predicted for lymph node involvement, treatment response, recurrence risk and overall survival (3). Similarly, the degree of variability of FDG uptake (FDGhetero) across a primary cervical tumor predicted for lymph node involvement, treatment response, local recurrence, and progression-free survival (4). Earlier research also found that primary cervical metabolic tumor volume (MTV) assessed on FDG-PET is associated with progression-free and overall survival (5).

Based on these studies, a prospective pilot study was initiated to evaluate how SUVmax, FDGhetero, and MTV changed during chemoradiation, using week 2 and week 4 during-treatment PET, and analyzing how these changes correlated with response on 3-month posttherapy PET, as other research showed that response assessment at this time predicted long-term outcome and survival (6).

Methods

Patients

This prospective cohort study included 25 patients with newly diagnosed FIGO stage Ib1-IVa cervical cancer who were treated definitively with concurrent cisplatin and radiation. The study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office (HRPO 08-0804). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

All patients were treated with a combination of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), high-dose-rate (HDR) intracavitary brachytherapy, and weekly concurrent cisplatin (40 mg/m2) with curative intent. Each patient had six brachytherapy implants, with standard tandem and ovoid applicators, given approximately weekly and interspersed with the EBRT.

Each patient underwent FDG-PET/CT of the pelvis during weeks 2 and 4 of treatment. Treating physicians were blinded to the results of the during-treatment PET until after the completion of all treatment. Generally, the week 2 scan was performed just prior to the second HDR insertion, and the week 4 scan was done just before the fourth HDR. For the week 2 scan, the average lymph node region EBRT dose, given in 2 Gy equivalent dose, was 1289 cGy (range 180–2300 cGy) and the average central pelvis dose (EBRT plus HDR brachytherapy in 2 Gy equivalent dose) was 1580 cGy (range, 950–2620 cGy). The corresponding doses at the week 4 scan were 2765 cGy (range, 1240–4200 cGy) and 3895 cGy (range, 2200–5050 cGy), respectively. Pretreatment PET-positive lymph nodes were generally treated with a slightly higher dose than the lymph node region, using an integrated boost technique.

PET imaging

All patients underwent standard of care pretreatment FDG-PET/CT for identifying lymph node involvement and for radiation therapy treatment planning. As part of this research study, FDG-PET/CT was performed during weeks 2 and 4 of treatment. Patients generally also underwent repeat standard of care FDG-PET/CT 3 months after completing chemoradiotherapy to assess disease response. Five patients did not undergo the posttreatment PET: 1 withdrew consent after the first during-treatment PET, 1 had surgery prior to PET, 1 died prior to the 3-month scan, and 2 were lost to follow-up prior to the 3-month scan.

All FDG-PET/CT images were performed on a Siemens Biograph 40 scanner. The pretreatment and posttreatment studies were whole-body PET/CT scans, while the two during-treatment PET/CT studies included just the pelvis region. The PET/CT images were interpreted both separately and in fused mode. Patients fasted at least 6 hours prior to administration of FDG, and blood glucose was less than 200 mg/dL for all scans. Studies were performed an average of 67 minutes (range 48–105 minutes) after FDG injection; the uptake time of the during treatment PET studies was matched to that of the pretreatment study. For all PET/CT studies, urinary tract activity was minimized by placement of a Foley catheter before injection of FDG and by administration of furosemide and intravenous fluids after the injection of FDG.

Image Analysis

For the pretreatment, week 2 and week 4 PET studies SUVmax, FDGhetero, and MTV were recorded. SUV is a semi-quantitative measure of radiotracer uptake calculated by the following formula:

In this study the maximum-pixel SUV (SUVmax) within a region of interest encompassing the tumor was used. To determine FDGhetero, the derivative of the threshold-volume curve was created using 40–80% thresholds (relative to the tumor SUVmax), as described previously (4). FDGhetero is a dimensionless measure of the variability of FDG uptake SUV = within the metabolic tumor volume of the primary cervical tumor; typical values range from approximately −6.2 (highly heterogeneous tumor) to −0.16 (minimally heterogeneous tumor). MTV of the cervical cancer was measured from the PET images using the 40% threshold of the SUVmax, as described previously (5).

Outcome Analysis

The response on the 3-month posttreatment PET/CT was scored as no evidence of disease (responder) vs. persistent or new disease (nonresponder).

Statistical Analysis

StatView®, SAS Institute Inc. Version 5.0.1 software was used for the analysis. P < 0.05 was set as the threshold for significance for all study outcomes. The baseline, week 2 and week 4 SUVmax, FDGhetero, MTV, and degree of changes in these factors were compared with the posttreatment PET/CT using ANOVA and unpaired t-test. There was no formal sample size estimate for this pilot study.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Twenty five patients enrolled on the study from September 2008 through October 2010. Initial patient characteristics are included in Table 1. The average pretreatment PET characteristics were: primary cervix tumor SUVmax was 17.8 (range, 6.2–32.3), FDGhetero was −1.33 (range, −6.2– −0.16), and MTV 55.4 cm3 (range, 7.6–251.1 cm3).

Table 1.

Demographic, tumor, and PET findings in study cohort.

| Category | All Patients (n=25) | Patients with Post- treatment PET (n=20) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, average (range) | 52 (25–85) years | 48 (25–74) years |

| Stage | ||

| IB1 | 2 | 1 |

| IB2 | 3 | 1 |

| IIB | 9 | 7 |

| IIIA | 1 | 1 |

| IIIB | 8 | 8 |

| IVA | 2 | 2 |

| Lymph node status | ||

| None | 6 | 6 |

| Pelvic only | 12 | 9 |

| Pelvic and para-aortic | 7 | 5 |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 20 | 17 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 2 | 0 |

| Pre-treatment PET Findings | ||

| Average SUVmax | 17.8 (6.2–32.3) | 17.8 (8.6–32.3) |

| Metabolic tumor volume | 55.4 cc (7.6–251.1) | 61.8 cc (10.4–32.3) |

| FDGhetero | −1.33 (−6.2 to −0.16) | −1.49 (−6.2 to −0.23) |

During-treatment FDG-PET changes

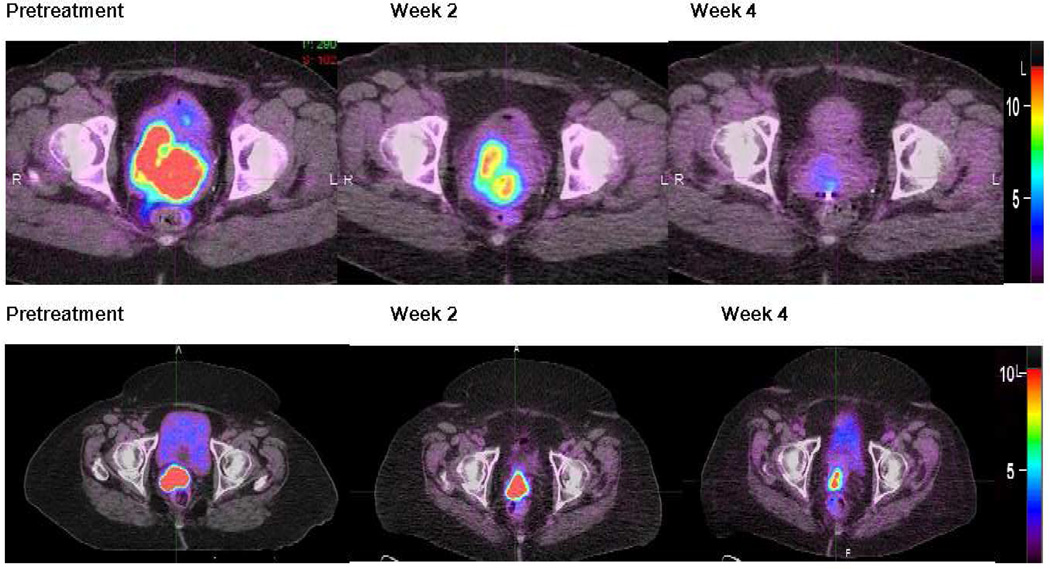

Figure 1 shows examples of the changes in primary cervical tumor FDG uptake during the course of therapy; qualitatively, we noted that the areas of highest FDG uptake remained relatively consistent on serial imaging. The average SUVmax, FDGhetero, and MTV pretreatment and at weeks 2 and 4 are shown in Table 2 for all patients and separately for posttreatment responders and nonresponders. No patient demonstrated a complete metabolic response (CMR) in the primary cervical tumor by the week 4 PET, but 5 out of the 19 patients with pelvic lymph node involvement pretreatment showed a CMR in their pelvic lymph nodes by week 4.

Figure 1.

Axial images from pretreatment, week 2, and week 4 FDG-PET/CT for two patients showing the stability of the location of the high FDG uptake regions. The SUV scale is shown on the far right of each set of images.

Table 2.

Pretreatment and during-treatment FDG-PET results in responding (n=15) and nonresponding (n=5) patients based on the 3-month posttreatment FDG-PET response assessment.

| Factor | Pre-treatment | Week 2 | Week 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUVmax (all patients) | 17.8± 6.99 | 11.6 ± 4.27 | 7.5 ± 3.20 |

| Responders | 16.5 ± 6.99 | 12.0 ± 4.58 | 6.9 ± 3.03 |

| Nonresponders | 21.6 ± 6.80 | 13.0 ± 4.18 | 10.3 ± 2.48 |

| P value (responders vs. non) | 0.18 | 0.66 | 0.037 |

| FDGhetero (all patients) | −1.33 ± 1.37 | −1.20 ± 1.28 | −0.91 ± 0.70 |

| Responders | −1.00 ± 0.76 | −0.72 ± 0.35 | −0.63 ± 0.35 |

| Nonresponders | −2.94 ± 2.22 | −2.97 ± 2.05 | −1.61 ± 0.67 |

| P value (responders vs. non) | 0.0076 | 0.0004 | 0.0005 |

| MTV (all patients) | 55.4 ± 55.1 | 51.0 ±51.4 | 38.7 ± 29.3 |

| Responders | 42.4 ± 30.9 | 32.0 ± 15.4 | 26.4 ± 14.4 |

| Nonresponders | 120.1 ± 89.1 | 121.1 ± 82.1 | 68.8 ± 27.8 |

| P value (responders vs. non) | 0.0076 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 |

non = nonresponders

FDG-PET changes during treatment and posttreatment response

Of the 20 patients who underwent a 3-month posttreatment FDG-PET, 15 showed CMR (no evidence of disease), and were classified as responders. Five patients had foci of persistent metabolically active disease and 2 of these also showed new sites of disease; these patients were classified as nonresponders. Clinical response was noted at the time of the 3-month post-treatment PET and 4 out of the 5 PET nonresponders were thought to have no evidence of disease based on clinical exam. At all 3 imaging times, nonresponders showed higher SUVmax, larger average tumor volumes, and greater FDGhetero compared to responders.

Stage and histology were not significantly associated with posttreatment response. However, the presence of positive para-aortic lymph nodes on pretreatment PET was correlated with posttreatment response (p=0.0038). Four of the 5 non-responders presented with para-aortic lymph nodes at diagnosis.

SUVmax

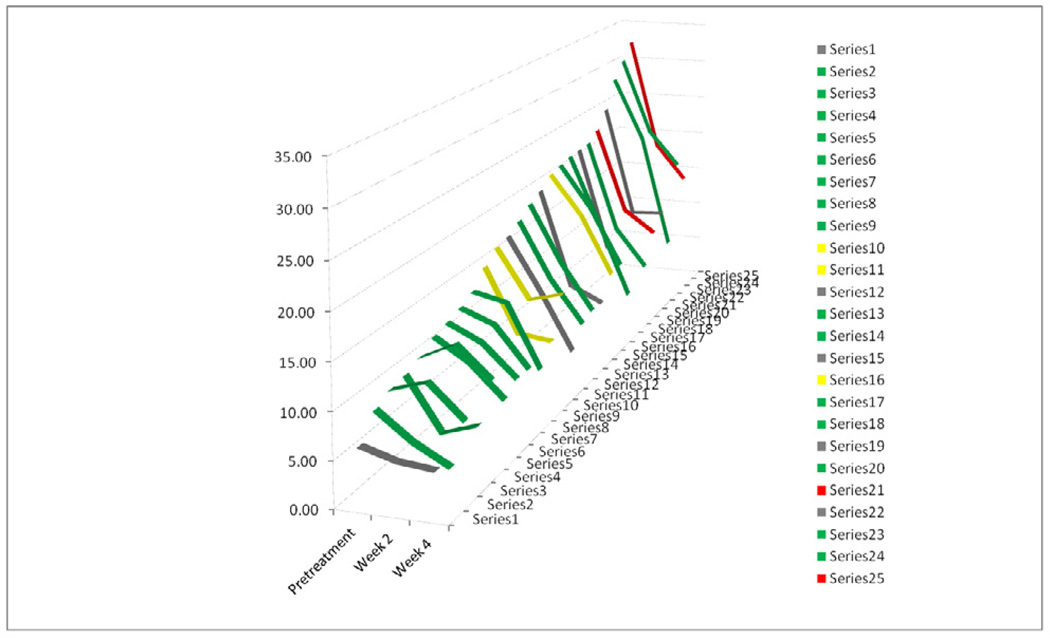

For all patients, the decrease in average SUVmax was similar from pretreatment to week 2 and from week 2 to week 4, approximately 34%. The decline in SUVmax during treatment is shown for all patients individually in Figure 2. Most tumors showed progressively declining SUVmax. Patient 11 received all the prescribed brachytherapy but did not receive all the prescribed external beam radiation.

Figure 2.

Changes in SUVmax during treatment

Line graph of SUVmax pretreatment and at week 2 and week 4 for all 25 patients. Patients in green showed no evidence of disease on the 3-month post-treatment PET, while those in yellow had a persistent disease, those in red had new sites of disease and those in grey did not undergo the 3-month post-treatment FDG-PET.

By week 4, SUVmax decreased by over 50%, comparing the average week 4 and pretreatment values. All patients had greater than 15% decrease in SUVmax by week 4. Only 2 patients had a decrease in SUVmax less than 25% by week 4 and both of these patients had a complete metabolic response on the 3-month posttreatment scan.

Week 4 SUVmax was significantly associated with posttreatment PET response (p=0.037). Interestingly, posttreatment responders show a lower rate of decline in SUVmax from pretreatment to week 2 (~27%), than from week 2 to week 4 (~42%). In contrast, the nonresponders showed a greater difference in the average pretreatment to week 2 values (~40%), with a decrease of around 21% from week 2 to week 4. Responders and nonresponders showed a significantly different decrease in SUVmax (p = 0.0488). The mean pretreatment SUVmax of responders did not differ significantly from that of nonresponders, although all nonresponders had a pretreatment primary cervical tumor SUVmax over 15.

FDGhetero

Mean FDGhetero decreased pretreatment to week 2 and from week 2 to week 4 for all patients, and responding patients showed a similar pattern. Nonresponding patients showed higher FDGhetero values, as compared to responding, and showed little change in FDGhetero from pretreatment to week 2. Pretreatment (p=0.008), week 2 (p=0.0004), and week 4 (p=0.0005) FDGhetero were all significantly associated with posttreatment PET response, with higher absolute values predicting for worse response. For all patients, the degree of change in FDGhetero between pretreatment and week 2, pretreatment and week 4, and between weeks 2 and 4 were not significantly associated with outcome. However, there was a significant difference over time for the responders compared to the nonresponders (p = 0.0169).

Metabolic tumor volume

A greater decline in PET MTV was seen from week 2 to 4 than from pretreatment to week 2. Responders showed a greater decline in MTV pretreatment to week 2 and approximately 38% decrease in MTV by week 4. In contrast, nonresponders showed little change in MTV from pretreatment to week 2, but by week 4 showed around a 43% decrease in MTV from pretreatment but still had significantly larger average tumor volumes than responders. Pretreatment MTV was significantly associated with posttreatment PET response (p=0.008), and the change in MTV was significantly different for the responders compared to the nonresponders (p = 0.0282).

Discussion

Performing FDG-PET during treatment offers a unique opportunity to assess response to therapy prior to the completion of treatment, which could allow for modifications to improve the long-term outcome for patients. During-treatment imaging was initially applied for chemotherapy treatment assessment (7, 8). More recently, various groups have assessed during-treatment PET response with radiation or chemoradiation for cancers of the lung, rectum, and other sites (9–14). Although different time points and treatment regimens were used, most of these studies have been able to use PET parameters (mostly SUVmax) to identify patients with favorable and unfavorable responses.

This pilot study evaluating the changes in FDG uptake of primary cervical tumors during chemoradiation found that pretreatment FDGhetero, pretreatment MTV, week 4 SUVmax, and week 4 FDGhetero were all significantly associated with posttreatment PET response. Additionally, patients with nonresponding tumors had greater average SUVmax, FDGhetero, and MTV at all times, compared to responders. For all patients, SUVmax shows a similar rate of decline pretreatment to week 2 and week 2 to week 4, and areas of highest FDG uptake remained relatively consistent during treatment. On average, cervical MTV shows a greater degree of decrease from week 2 to week 4 than from pretreatment to week 2 and decreased at a slower rate than SUVmax. Based on this pilot study, pretreatment and week 4 of chemoradiation are the best times for an early prediction of treatment response. Additional study with a larger group of patients would be needed to confirm these findings.

The changes we observed in SUVmax and MTV compare favorably with previous studies, but also show some differences. Van Baardwijk et al. evaluated changes in SUVmax in 23 lung cancer patients during radiation (12). They found significant intra-individual variability for the changes in SUVmax, but poorly responding patients tended to have higher values at baseline and during treatment, as seen in our study. Just as we saw the areas of highest FDG uptake remaining in a consistent location as treatment progressed, others have also observed stability of high FDG uptake regions for lung and rectal tumors undergoing during-treatment PET (13, 14). Earlier cervical research showed 29% reduction in volume after 11 fractions and 50% reduction after approximately 4 weeks of treatment, while we saw an approximately 25% decrease at 2 weeks and a 40% decrease after 4 weeks (15). In contrast to previous work that noted similar rates of decline in SUVmax and volume (~50% by 16 days), we saw greater and faster decline in SUVmax than volume. This difference may be due to the timing of the PET scans during therapy or differences in pretreatment tumor volumes and SUVmax. Other studies have also suggested that FDG uptake decreases earlier than tumor shrinkage (16, 17).

In previous research that included later during-treatment PET imaging, 6 cervical patients were observed to have a complete metabolic response (CMR) during treatment (18). Similarly, another cervical cancer study found 7 patients with a visual CMR after an average of 23 Gy (11). No patients in our study showed a CMR of the primary cervical tumor by week 4. Only 2 patients in the present study did not experience a partial metabolic response (reduction of at least 25%by EORTC criteria (16)) by week 4 imaging, and both patients subsequently had a CMR on the posttreatment PET. Perhaps if the present group of patients had been imaged at a later time point some CMR would have been observed.

While the goal of the present study was to evaluate changes in FDG uptake during chemoradiation, our findings reflect to earlier research which provided the foundation for developing this protocol, as patients with persistent disease had high pretreatment SUVmax, FDGhetero, and MTV (3–5). Previous work showed that SUVmax was not significantly correlated with MTV or FDGhetero (3,4). The relationship between FDGhetero and tumor volume has been addressed by Brooks and Grigsby who showed mathematically that FDGhetero as calculated in this research is a non-spatial metric, which is a representative surrogate for tumor volume (19). While pretreatment SUVmax was not statistically significantly associated with posttreatment response, all 5 of the patients with nonresponding tumors had a pretreatment SUVmax greater than 15; in our earlier study, a pretreatment SUVmax greater than 13.3 distinguished poor responders (3). Other research in rectal cancer suggested that during-treatment assessment was superior to pretreatment assessment for predicting subsequent pathologic response (20), whereas our study we found that both pretreatment and week 4 PET values were significantly correlated to posttreatment response and thereby long-term outcome.

While our pilot study offers several important findings, it also has some limitations. Our study included 25 patients and only 20 underwent the planned 3-month posttreatment PET. Patients had variable pretreatment prognostic factors including SUVmax, FDGhetero, MTV, stage, and lymph node status. There were some differences in the radiation doses the patients had received at the timing of the 2 during-treatment PET scans. Additionally, our results may be less transferable to patients who are treated with a lower brachytherapy dose or who only receive brachytherapy following external beam radiation. Despite these limitations, the study yielded several significant and new observations.

Our study is unique to evaluate the combination of SUVmax, FDGhetero, and MTV pretreatment and at two time points during treatment and also using the 3-month posttreatment PET as a surrogate for long-term outcome. Our results provide valuable new information about how cervical tumors respond during treatment, with week 4 SUVmax and FDGhetero and pretreatment FDGhetero and MTV being the most useful PET metrics for risk stratification. It was also interesting to find that SUVmax shows a similar rate of decrease from pretreatment to week 2 and week 2 to week 4 and that cervical tumor volume regresses at a slower rate than SUVmax. Our study also confirms the negative prognostic value of high pretreatment SUVmax, FDGhetero and large tumor volume, as nonresponders tended to show these characteristics initially and during the course of treatment.

Conclusion

With 20–40% of cervical cancer patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation experiencing recurrent or persistent disease (1, 2), being able to identify these high risk patients in order to provide treatment intensification could have significant benefits. The present study confirms the prognostic value of pretreatment PET-based factors and identifies week 4 of treatment as another valuable time point for providing an early assessment of response, specifically with week 4 SUVmax and FDGhetero and pretreatment FDGhetero and MTV being the most useful PET-based prognostic factors for identifying patients at risk for new or persistent disease following concurrent chemoradiation. With adjuvant chemotherapy representing a possible means of treatment intensification, the combination of pretreatment and week 4 FDG-PET/CT could potentially be a useful means of identifying patients who would benefit most from this additional treatment.

Acknowledgement

Funding provided by RO1 CA136931 and 2008 RSNA Resident Research Grant #RR00807.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Eifel PJ, Winter K, Morris M, et al. Pelvic irradiation with concurrent chemotherapy versus pelvic and para-aortic irradiation for high-risk cervical cancer: an update of radiation therapy oncology group trial (RTOG) 90-01. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:872–880. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, et al. Metabolic Response on Posttherapy FDG-PET Predicts Patterns of Failure After Radiotherapy for Cervical Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd EA, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, et al. The standardized uptake value for F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose is a sensitive predictive biomarker for cervical cancer treatment response and survival. Cancer. 2007;110:1738–1744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidd EA, Grigsby PW. Intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity of cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5236–5241. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller TR, Grigsby PW. Measurement of tumor volume by PET to evaluate prognosis in patients with advanced cervical cancer treated by radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, et al. Association of posttherapy positron emission tomography with tumor response and survival in cervical carcinoma. JAMA. 2007;298:2289–2295. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rozental JM, Levine RL, Nickles RJ, et al. Glucose uptake by gliomas after treatment. A positron emission tomographic study. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1302–1307. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520480044018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haberkorn U, Reinhardt M, Strauss LG, et al. Metabolic design of combination therapy: use of enhanced fluorodeoxyglucose uptake caused by chemotherapy. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1981–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong FM, Frey KA, Quint LE, et al. A pilot study of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scans during and after radiation-based therapy in patients with non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3116–3123. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wieder HA, Brucher BL, Zimmermann F, et al. Time course of tumor metabolic activity during chemoradiotherapy of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:900–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjurberg M, Kjellen E, Ohlsson T, et al. Prediction of patient outcome with 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography early during radiotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1600–1605. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181c00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Dekker A, et al. Time trends in the maximal uptake of FDG on PET scan during thoracic radiotherapy. A prospective study in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aerts HJ, Bosmans G, van Baardwijk AA, et al. Stability of 18F-deoxyglucose uptake locations within tumor during radiotherapy for NSCLC: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1402–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Bogaard J, Janssen MH, Janssens G, et al. Residual metabolic tumor activity after chemo-radiotherapy is mainly located in initially high FDG uptake areas in rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;99:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin LL, Yang Z, Mutic S, et al. FDG-PET imaging for the assessment of physiologic volume response during radiotherapy in cervix cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U, et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price P, Jones T. Can positron emission tomography (PET) be used to detect subclinical response to cancer therapy? The EC PET Oncology Concerted Action and the EORTC PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:1924–1927. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarz JK, Lin LL, Siegel BA, et al. 18-F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography evaluation of early metabolic response during radiation therapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1502–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks FJ, Grigsby PW. Current measures of metabolic heterogeneity within cervical cancer do not predict disease outcome. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen MH, Ollers MC, Riedl RG, et al. Accurate prediction of pathological rectal tumor response after two weeks of preoperative radiochemotherapy using (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]